Abstract

We evaluated the effects of a culturally adapted evidence-based HIV prevention intervention (Mpowerment), named “Tayf”, on condom use and HIV testing among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in Beirut. A 2-year implementation of Tayf was carried out independently and in parallel with a research cohort of 226 YMSM who were surveyed at baseline and months 6, 12, 18 and 24 after Tayf initiation. Primary outcomes were (1) any condomless anal sex with HIV-positive or unknown status partners in the past 3 months, and (2) HIV testing in the past six months. Hierarchical logistic regression models examined the association of Tayf participation with the outcomes averaged across all assessments, and the moderating effect of Tayf participation on change in the outcomes over the follow-up period. A total of 331 YMSM attended at least one event, including 33% of the cohort. Tayf participation was associated with a higher rate of any condomless sex with HIV-positive or unknown status partners averaged across the five assessments, but there was no moderating effect of Tayf participation on change in this outcome over time. Tayf participation was associated with higher HIV testing when averaged across all assessments, but its interaction with time showed that the strength of this association diminished over time. In conclusion, Tayf proved feasible and acceptable in Beirut, but with limited effects. Further work is needed, including innovative publicity and marketing strategies, to bolster effects in high stigma settings where security and legal risks are prominent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While HIV prevalence is generally low in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, incidence rates have been increasing over the last several years [1], and prevalence rates are particularly high in marginalized key populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM). A review of MSM research in MENA revealed HIV prevalence rates as high as 28% in some subgroups in Pakistan in 2010 [2], and an estimate of 12.3% was found among MSM in Lebanon by a study published in 2017 [3]. MSM in Beirut, as elsewhere in MENA, face high levels of societal discrimination and stigma; yet, gay social life in the city is increasingly open, and young MSM (YMSM) in particular are more comfortable with their sexuality and self-expression. However, increased freedom of sexual expression may heighten HIV risk as YMSM explore their sexuality in a context of limited awareness and underdeveloped negotiation skills for safer sex [4, 5], increased risk from the rise of sex tourism in Beirut [6], and influx of MSM refugees from Syria and Iraq who face a multitude of factors that increase their risk [7].

HIV prevention for MSM in Lebanon and MENA more generally is limited to condom promotion, free HIV testing and awareness campaigns, but a more comprehensive approach is lacking. Mpowerment (MP) is one of only two CDC-identified evidence-based HIV prevention interventions for YMSM [8]. MP is a multi-level intervention that reaches out to all YMSM in a community by mobilizing men to encourage their friends to reduce risk behavior and join the program (informal outreach), along with holding social activities to promote safer sex and conducting outreach to YMSM at venues where they congregate (formal outreach). MP provides YMSM with skills, support and confidence to find solutions within themselves for sexual health, and seeks to affirm the validity and rights of same-sex behavior and identities. Two controlled trials of MP in the U.S. have demonstrated its efficacy in increasing condom use [9,10,11], and it has been shown to be cost-effective [12]. However, while more recent projects use MP to also increase HIV testing, its effects on testing have not yet been established in the literature. MP is adaptable to diverse cultural settings because while the program provides a structure for empowering communities and individuals to adopt and promote sexual health behavior, the content and delivery of the program is determined mostly by the participating local YMSM.

MP has been widely implemented in the U.S., and a few settings within Latin America and Southern Africa, but not in an Arabic setting.

For MP to be successful, the gay community in which it operates needs to be adequately developed such that YMSM are able to be empowered to advocate and mobilize together with their peers. Beirut is located on the fringe of both Europe and the Middle East, and this is reflected in a culture that has both progressive and conservative influences. Beirut has had a history of internal conflicts that have contributed to a tolerance of cultural differences, providing an opportunity for the gay community to develop more easily than in some other areas. For the past twenty years, various community-based organizations have arisen in Beirut to fight for greater societal awareness and tolerance of homosexuality, and improved gay community organization and advocacy. Support for gay rights in the mainstream media has markedly increased, and the Lebanese Psychiatric Society recently declared homosexuality is not a disease. Gay life in Beirut thrives in meeting places such as university social clubs, gay bars and dance clubs, and gay-friendly cafes. However, these developments are counter balanced by a sustained high level of societal stigma and discrimination towards homosexuality [13]. Homosexuality remains illegal, resulting in an omnipresent risk for arrests and police harassment. Many MSM live in a chronic state of anxiety and fear regarding public expressions of their sexual identity, particularly among Syrian refugees who now represent one-third of the population and whose legal status in the country is highly tenuous [14]. Most YMSM are particularly fearful that their families may learn that they are attracted to and have sex with men [15].

After completing formative research built on peer ethnography, focus groups and consultations with a Community Working Group (CWG) to inform the cultural adaptation of the intervention to the needs of YMSM in Beirut [16], we conducted a 2-year pilot implementation and evaluation of Tayf (which means “spectrum” in Arabic, and is the name given to the MP program by its membership in Beirut) to assess its effects on sexual risk behavior and HIV testing.

Methods

Study Design

This study was an open trial evaluation of a 2-year implementation of Tayf that used a longitudinal cohort and pre- and post-intervention evaluation design to examine the intervention effects on (1) condomless anal sex with HIV-positive or unknown status partners in the past three months, and (2) HIV testing within the past six months. Assessments were conducted at baseline, which took place over the course of enrollment (July 2016 to February 2017), and at four follow-up time periods starting at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after initiation of Tayf implementation (March 2017); therefore, participants were followed over a total of 30 months.

Participants enrolled in the study represent the larger YMSM community in greater Beirut. Diffusion of innovation theory [17], upon which the social-network driven Tayf intervention is based, posits that intervening directly with at least a significant subset of a community will result in effects being diffused across the whole community with the aid of informal outreach (recipients spreading the work throughout their social networks). Therefore, even if participants in the cohort do not participate in any Tayf activities, they may still receive benefit indirectly, and changes in primary outcomes observed in the study sample may represent changes that are occurring throughout the YMSM community.

Study Participants

Cohort participants were recruited primarily through long chain peer referral methods, though other methods such as recruitment flyers, postings on social media and word of mouth were added near the end of recruitment. Eligibility criteria consisted of being biologically male and male-identified, age 18 to 29 years, fluent in English or Arabic, residing in greater Beirut, and having had oral or anal sex with a man in the past 12 months. For the long chain peer referral methods, recruitment began with a small number of eligible persons designated as “seeds” who were identified through community organizations working with MSM and our CWG, and were purposely selected to be well-connected and to represent the diversity of the community (in terms of age, socioeconomic status, religious affiliation). All participants received three recruitment coupons to recruit members of their social network, resulting in multiple waves of participants. Participants were instructed to give a coupon to eligible MSM peers who were interested in participating and to inform the recruit to call the study coordinator for coupon verification, eligibility screening, verbal consent procedures, and scheduling of an interview. Participants were compensated $40 for completing each assessment, as well as $10 for each peer recruited (up to three) into the study; participants who completed all four follow-up assessments received an extra $50 bonus (therefore, a maximum of $280 could be received).

Tayf Intervention

Like MP, Tayf draws on theories of individual and community behavior change, including the IMB model [18], Freire’s principles of empowerment education [19], theories about community and individual empowerment [20, 21], and diffusion of innovation theory [17]. The program sought to facilitate the empowerment of YMSM and the YMSM community, build acceptance of oneself as an MSM, and build a community of YMSM who support each other in a myriad of ways, including about safer sex and HIV testing. Tayf, adapted for YMSM in Beirut through community input and ethnographic research [16], was implemented by two full-time YMSM Coordinators in tandem with volunteers and was composed of six interrelated core elements (briefly described below; see www.mpowerment.org) that act synergistically and focus on individual, interpersonal, social and structural issues for change. The adapted model differed from the evidence-based MP model in a few key areas, including having constricted Formal Outreach and Publicity due to security/safety concerns related to the risk of privacy violations and police action.

The Core Group, made up of YMSM volunteers, made key decisions for the project and was actively involved in programmatic implementation. Core Group meetings took place weekly and were usually attended by ten to fifteen YMSM. Members could join or leave the Core Group at any time. Everyone from the YMSM community was welcome to attend.

Below the Belt groups were one-time, 3-h meetings for six to twelve YMSM that were held every other month and facilitated by the Coordinators. These groups used a structured format to facilitate discussions and role plays where YMSM could learn about negotiating safer sex and the benefits of regular HIV testing, building communication skills, and practicing talking with friends about the importance of safer sex and HIV testing.

Formal Outreach consisted of social events of all sizes, which were meant to draw YMSM to Tayf, promote safe sex and HIV testing, build a stronger sense of community, and facilitate the empowerment of young men and the YMSM community. Publicity was used to promote the existence of Tayf and its social events. The program averaged two to three social events per week, including weekly small events (10–20 people) such as movie nights, twice-a-month medium-sized events (21–50 people) such as camping trips and community forum events (discussions on sexual health topics such as negotiating closed versus open relationships), and quarterly large events (over 50 people) such as dance parties. The intent was to infuse all events with messages about sexual health and regular HIV testing, and the importance of supporting friends about these issues (Informal outreach, see below). However, this was limited because of concerns that written materials, condoms, and lubricants to be distributed could fall into the hands of police who might shut down the project, or family members at home which could inadvertently “out” the person. Likewise, activities at the social events could not be very explicit about gay sexuality. Formal Outreach also typically includes YMSM volunteers going to gay venues to distribute materials promoting safe sex and HIV testing, but this could not be done in Beirut because of security concerns at such venues. Publicity was largely limited to Tayf’s Facebook page (which was a closed page, accessible only to members for privacy and security purposes) and Whatsapp group communication for registered Tayf members. Postings on Facebook and Whatsapp were only allowed to feature stock photos of men or animated figures, not photos of actual members participating in events, and could not be erotic or overtly sexualized. The address of Tayf’s Center (described below) was also never posted, and only shared through direct communication with a Coordinator.

Informal Outreach involved YMSM encouraging their friends to have safer sex, get tested for HIV or get into care and on medication if living with HIV. Support for talking with friends and acquaintances about these issues was emphasized at Core Group and Below the Belt meetings. Informal Outreach is critical to transforming community norms that support safer sex, HIV testing and medication adherence, especially given the severe limitations on Formal Outreach and the reliance on diffusion of information and norms for community-level effects. Informal Outreach often typically includes men giving their friends materials about the project and the project’s messages about safe sex and HIV testing, but this was considered too risky to distribute in fear of the material falling inadvertently into the hands of police or family.

Tayf was housed in a large apartment and was where most project activities were held. The Tayf Center served as a safe space where YMSM could be themselves and experience support, belonging, and friendship while critically reflecting on their sexual behavior, attitudes, relationships, and identity. Information that was sensitive and affirming for YMSM was on display about where to obtain HIV testing; however, materials more explicit about sexuality were considered too risky if authorities were to visit the space unexpectedly.

Intervention Training, Supervision, and Oversight

Over five days, Kegeles, Tebbetts, Mutchler and Wagner used an adapted MP training manual to train the Coordinators (and lead supervisor, Ballan) on how to facilitate all Tayf activities, as well as training on group facilitation, community mobilization, and conflict management. Two pilot Below the Belt groups were conducted, one with the CWG which was conducted in English by Kegeles and Tebbetts (with the Coordinators being participants), and the second conducted in English by the Coordinators with YMSM participants (and Kegeles, Tebbetts and Wagner observing). Although training was conducted in English, all program activities were implemented in Arabic, and any promotional or educational materials were also in Arabic. All project staff were fluent in English, which is typical for Lebanese with at least a secondary level education, in order to facilitate supervision and oversight. The Project Director (Ballan) was the primary supervisor of the Coordinators, while Tebbetts and Wagner assisted in overseeing the implementation via weekly calls with the Coordinators and Ballan and quarterly in-person visits to Beirut.

Measures

The survey was administered in English or Arabic, depending on the preference of the participant, with computer-assisted interview software. The survey was developed in English and translated into Arabic using standard translation and back translation methods. Participants were given the option of completing the survey on their own or having the interviewer administer the survey; no statistics were collected, but the study interviewers reported that it was very rare for a participant to choose to self-administer the survey.

Sociodemographics

These consisted of age, education level, employment, monthly income, religious affiliation, country of birth, nationality, sexual orientation, and relationship status. For analysis, response categories were combined to create binary indicators for measures of age less than 25 years, having at least some university education, very low monthly income (< $500 USD; note that U.S. dollars is a regular currency in Lebanon), Lebanese nationality, self-identification as gay, Christian religious affiliation, current employment, and in a committed relationship. Respondents were also asked to indicate on a 5-point response scale “to what degree are you open (out) as gay, bisexual, or as a man who has sex with men” in their personal/social life, and in the workplace or at school, in separate questions; binary indicators were derived to represent whether the respondent was open mostly or completely in these two areas of their lives.

Sexual Behavior

Participants were asked to indicate the number of male sex partners in the past three months. For receptive and insertive anal intercourse, participants were asked how many times they engaged in the act over the past three months, how many of those acts were condomless, and the HIV status of the partners with whom condomless acts were engaged with. To assess partner HIV status, participants were asked to indicate how many of these partners “told you he was HIV negative and you had no reason to doubt it,” “you knew this man was HIV positive,” and “you were not completely sure of this man’s HIV status.” In analysis, a binary variable was created to represent whether or not the participant reported condomless anal sex with a partner whose HIV status was believed to be positive or unknown, in the past three months; participants who reported no anal sex in the past three months were classified as not having engaged in any type of condomless anal sex.

Variables were also created to represent the proportion of condomless receptive and insertive anal sex events. The distribution of these data was u-shaped, so we converted each of these two variables to a three-level categorical variable in which 0 = 0% of the events were condomless, 1 = 1–99% were condomless, and 2 = 100% were condomless. Note that these two variables were only calculated for participants who reported anal sex in the past three months; HIV status of the partner was not accounted for in this variable, since this was not assessed for each anal sex event.

History of HIV Testing

At baseline, participants were asked whether they had ever tested for HIV. Those who had tested were then asked if they had tested within the past six months and the result of their last test. At follow-up, participants were asked about HIV testing since their last assessment (or past six months). For analysis, at each time point a binary variable was derived to represent whether the respondent reported getting HIV-tested in the past six months.

Participation in Tayf Activities

Tayf activities were broken down into five categories, and we created an index of participation that assigned a weight to each category, with the magnitude of weight corresponding to the expected “potency” of the activity for impacting HIV prevention. Similar to a weighting system used by Shelley et al. in their evaluation of Mpowerment, [22] participation in a Below-the-Belt group was awarded 5 points, followed by 4 points for attending a community forum discussion, 3 points for attending a core group meeting, 3 points for attending a social event (regardless of whether it was a small, medium or large event), and 2 points for hanging out at the Tayf center. At each assessment wave, we constructed a composite score of Tayf participation by multiplying the number of times a participant attended each of these types of Tayf activities with its appropriate weight. A cumulative index of Tayf participation was calculated by summing the composite score across all four follow-up assessments.

Analysis

The analytic sample included participants with a baseline survey and one or more follow-up survey(s), and who reported not being HIV-infected at baseline (given the focus of this analysis on HIV testing and condomless anal sex that risked acquisition of HIV). Initial analyses compared the analytic sample with those completing only a baseline and no follow-up assessments. For binary and continuous variables, we conducted 2-tailed, independent t-tests for the difference of two proportions or means, with degrees of freedom equal to n-1; while for categorical variables with more than two levels, we used a chis-squared test. Given that there were differences between these two groups, we estimated nonresponse weights to account for attrition using a logistic regression model with response status as the binary outcome. Individual-level probabilities predicted from logistic regressions were used for inverse probability weighting. Predictors in the logistic model included: age less than 25 years, Lebanese nationality, gay self-identified sexual orientation, very low monthly income, Christian religious affiliation, employment status, relationship status and likelihood of moving out of Lebanon within the coming year. Also, to address a few cases with missing values for key covariates, we conducted single imputation using a sequential regression multivariate imputation approach in SAS Proc MI [23]. Given that Tayf participation was not randomized, and it was a key independent variable in our planned regression models, we conducted a comparison of the individual-level characteristics of participants and non-participants along with statistical testing to identify significant differences.

The two primary outcomes to assess effects of Tayf were these binary variables: (1) any condomless anal sex with HIV-positive or unknown status partners in the past three months, and (2) any HIV testing in the past six months. Other outcomes included the 3-level categorical variables representing the proportion of condomless insertive and receptive anal sex events in the past three months. We computed mean, percentage and frequency of each outcome at each of the five assessment time points, with and without nonresponse weighting, and plotted raw or unadjusted trends of the average outcome. Post-intervention changes in outcomes were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE), with empirical (robust) standard errors used to construct 95% confidence intervals. This approach incorporates covariance within individuals and accounts for the lack of independence between multiple observations for an individual over time [24]. The binary outcomes were modeled with a logit link. Models included a parameter for time, which was coded as either ordinal (values of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) or with separate binary indicators for 6-, 12-, 18- and 24-month follow-up assessments.

Hierarchical regression models were conducted in three stages. In the first stage, models included the ordinal (linear time; model 1) or binary indicators of time (non-linear time; model 2), adjusted for individual-level characteristics to account for confounding. A significant time trend would serve as an indication of community change in the outcome, given that the entire community was potentially exposed to the intervention either through direct participation or diffusion of messaging (i.e., informal outreach). In the second stage, we added the cumulative index of Tayf participation at each wave as a covariate in the model to assess if the effect of the time trend, when significant, is sustained and robust [25]. The coefficient of the cumulative index in model 3 represents the overall association (or correlation) between Tayf participation and the outcomes averaged across the five assessments (including baseline or pre-intervention). By using a cumulative participation measure, we have assumed that once exposed to a Tayf activity, participation affects outcomes at the same and future waves (i.e., participation has both direct and lagged effects). In the third stage (model 4), we examined whether Tayf participation moderated change in the outcome over time by adding an interaction term between participation and time. All models included these covariates: age less than 25 years, any university education, Lebanese nationality, self-identification as gay, very low monthly income, Christian affiliation, employed status, relationship status and number of anal sex events in past three months. The number of anal sex events was included as a covariate to control for the extent to which frequency of anal sex could influence the likelihood of the respondent reporting at least one condomless event. To aid interpretation of the time trend, we calculated covariate-adjusted means or proportions (“recycled predictions”) [26] of each outcome at three distinct levels of Tayf cumulative participation (cumulative scores of 0, 20, 40), held covariates fixed and plotted them across assessments; for the prediction step, we used the third model when the interaction effect was significant, and the second model when it was not.

Results

Sample Characteristics

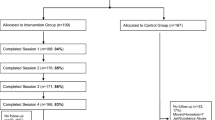

A sample of 226 YMSM enrolled in the study; eight participants self-reported being HIV-positive and were excluded from the analytic sample. Table 1 lists the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample of 226 participants and the sample of 218, as well as of those participants who only completed the baseline (n = 50) and those who completed at least one follow-up assessment (n = 168)—the latter of which comprised the analytic sample. Those who remained in the study past baseline were more likely to have some university education, to be Lebanese, to be employed, to not have very low income, and to be more likely to be open about their sexuality at work/school and in their personal/social lives. Of those who completed at least one follow-up, all but 20 completed multiple follow-up assessments and 137 (81.5%) completed the final month 24 assessment.

Tayf Implementation and Participation

Tayf was able to operate uninterrupted throughout the study, with consistent weekly Core Group meetings (attended consistently by 10–15 members), weekly small social events (up to 20 members per event; 124 events held over the 2-year implementation), monthly community forum events (29 events held), bimonthly medium (20–50 members per event) to large (> 50 members per event) social events (16 events held), and bimonthly Below-the-Belt groups (14 groups held). A total of 331 YMSM community members attended at least one Tayf event over the 2-year implementation.

Of the 168 research participants in the analytic sample, 56 (33.1%) reported ever participating in a Tayf event, including 31 who completed a Below the Belt group, 37 who attended at least one Core Group meeting, 27 who attended at least one community forum event, 52 who attended at least one social event (whether it be a small, medium or large event), and 29 who reported “hanging out at the center”. Among the 56 who reported any Tayf participation, the average cumulative index total was 21.9 (SD = 17.2; range: 3–57). Compared to study participants who reported no participation in Tayf, participants were more likely to be under age 25, more open in both personal/social and work/school settings, and more likely to be Christian (see Table 2); however, there were no differences with regard to other baseline sociodemographics and sexual behaviors.

Change in Sexual Behavior

At baseline, 153 of the 168 participants in the analytic sample reported any male sex partners in the past three months, and the mean was 4.8 partners (SD = 11.2; range: 0 to 120). Of these 153, 137 (89.5%) reported any anal sex with men during this time period; of these 137 men, 70 (51.1%) reported condomless anal sex, including 26 (19.0%) who had condomless anal sex with a partner whom they believed to be HIV-positive (n = 6) or of unknown HIV status (n = 20). When men who had no anal sex were included with men who had no condomless anal sex, the rate of condomless anal sex with HIV-positive or unknown status partners was 15.5% (26/168).

Among those who reported insertive anal sex with men in the three months prior to baseline, the mean number of insertive anal sex events was 7.6 (SD = 9.1; range: 1 to 48); the mean proportion of such events that were condomless was 26.7% (SD = 39.7%), including 57.4% who reported no condomless events, 22.2% with at least one but not all events being condomless, and 20.4% who reported all events being condomless. Among those who reported receptive anal sex with men in the three months prior to baseline, the mean number of receptive anal sex events was 7.9 (SD = 12.4; range: 1 to 100); the mean proportion of such events that were condomless was 36.9% (SD = 43.2%), including 45.6% who reported no condomless events, 27.7% with at least one but not all events being condomless, and 26.7% who reported all events to be condomless.

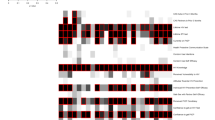

In the hierarchical regression models, when only time and the covariates were included as independent variables (models 1 and 2), there was a single significant main effect of time for the categorial variable representing proportion of insertive anal sex events that was condomless [OR (95% CI) = 1.16 (1.02, 1.32)]; over the course of the study, this proportion increased significantly (see Table 3). There was no significant time trend for the other outcomes. When the cumulative index of Tayf participation was added as a covariate to the models (model 3), it was associated with an increase (averaged across all assessments) in the rate of any condomless anal sex with HIV-positive or unknown status partners [OR (95% CI) = 1.03 (1.00, 1.06)] (see Table 3 and Fig. 1). In the sample as a whole, there was a significant downward time trend in the rate of any condomless sex with HIV-positive or unknown status partner [OR (95% CI) = 0.82 (0.68, 1.0)], but an upward time trend for proportion of insertive anal sex [OR (95% CI) = 1.21 (1.05, 1.40)] (see Table 3), which are depicted in Fig. 1. The cumulative index of Tayf participation was not associated with proportions of receptive or insertive anal sex events that were condomless.

Recycled predictions of sexual behavior outcomes from Table 3, covariate-adjusted main effects model (model 3) against assessment wave (baseline to month 24). Each model included the following covariates: age less than 25 years, any university education, Lebanese nationality, self-identification as gay, very low monthly income, Christian affiliation, employed status, relationship status and number of anal sex events in past three months. Models for proportions of insertive and receptive anal sex that were condomless were estimated amongst those reporting any anal sex

In model 4, which estimated the moderating effect of Tayf participation (cumulative index > 0) compared to no participation (cumulative index = 0) on change in the outcomes over the course of follow-up, the interaction effects were not significant for any of the sexual behavior outcomes (see Table 3). That is, the slope for those who participated in Tayf was not significantly different than the slope for the overall sample.

Change in HIV Testing

At baseline, 134 (78%) of the 168 participants reported ever being tested for HIV, including 77 out of 168 (45%) who had tested within the past six months. In the hierarchical regression models, when only time and the covariates were included as independent variables (models 1 and 2), there was a significant main effect of time [OR (95% CI) = 1.13 (1.02, 1.25)], suggesting that recent HIV testing increased significantly over the course of the study in the whole sample (see Table 3). When the cumulative index of Tayf participation was added to the model (model 3), the main effect of Tayf participation was positive and significant [OR (95% CI) = 1.03 (1.00, 1.06)], suggesting a positive association between Tayf participation and recent HIV testing when averaged across all assessments (see Table 3 and Fig. 2). The main effect of time was no longer significant. In model 4, the interaction between time and Tayf participation was significant and with a negative beta coefficient (see Table 3), suggesting that the association of Tayf participation with increased HIV testing diminished over the course of the 30-month follow-up period (see Fig. 2).

Recycled predictions of recent HIV testing from Table 3, covariate-adjusted main (model 3) and interaction effects (model 4) models against assessment wave (baseline to month 24). Each model included the following covariates: age less than 25 years, any university education, Lebanese nationality, self-identification as gay, very low monthly income, Christian affiliation, employed status, relationship status and number of anal sex events in past three months

Discussion

This pilot of Tayf, a cultural adaptation of one of the only evidence-based HIV prevention programs for YMSM, is the first such program ever implemented with YMSM in the Middle East. The study showed that the adapted model of MP was both feasible and acceptable in an Arabic well-developed gay community such as that in Beirut. Findings from the research cohort of YMSM who were mostly very young, well-educated and gay identified, showed stable rates of any condomless anal sex with positive or unknown HIV status partners, but increased HIV testing over the course of the 30-month follow-up. Men in the research cohort who chose to participate in Tayf were more comfortable with their sexuality and more frequently reported any condomless anal sex with positive or unknown HIV status partners, but also more likely to get frequently tested for HIV. However, Tayf participation did not moderate the change in high-risk condomless sex over the course of follow-up, and its association with higher HIV testing decreased over time.

Tayf was successfully implemented throughout the 2-year implementation period. The Core Group, which provides the leadership and manpower to carry out events, was held weekly with consistent strong attendance, although after the first few months there were fewer new members attending events. Below-the-Belt groups, social events of all sizes, and community forum events were all held consistently and were well attended. The program established strong collaborative partnerships with other community-based organizations that serve the sexual minority community of Beirut, co-hosting some events and supporting each other’s initiatives through active participation, information dissemination, and event promotion. The program’s membership opened its Center and most events to all segments of the sexual minority community, which served to strengthen solidarity and a sense of community. This was especially true for the transgender community, with specific events held to improve understanding of and support for transgender issues and individuals. Over time, transgender individuals experienced Tayf’s Center as a safe space and their participation in Tayf events increased.

The adaptation phase of the intervention, which was informed by focus groups, peer ethnography [16], and meetings with the Community Working Group, revealed the need to limit most aspects of Formal Outreach and Publicity about Tayf and its social events. This was done to protect participating members and the program’s continued existence in the face of challenges related to discrimination, harassment and legal issues surrounding homosexuality in Lebanon. This approach was successful in so far as there were no security incidents or conflicts with police authorities, nor were there any issues with the Center’s landlord or neighbors. However, one conservative religious group threatened a lawsuit against the community-based organization that administered Tayf, after which the project reduced further how explicit it was about sexuality and the promotion of upcoming events, and the address of the Center was not provided unless asked for and following a discussion with a Coordinator. Nevertheless, Tayf members generally felt safe and comfortable at the Center and attending Tayf events, although photography of participants was strictly prohibited.

Areas in which the program was less successful included the inability to engage a diverse range of YMSM in terms of age and economic class, and limited ability to attract a steady influx of new members throughout the duration of implementation. With very young men being predominant in the membership, the program and Center gained the perception that it was geared to the needs of very young MSM, and less relevant and appealing to “older” YMSM (e.g., men age 25–29). As noted above, risks related to breaches of privacy and security prevented the program from being able to use efficient methods of publicity and marketing, and this undoubtedly hampered the program’s ability to engage a larger and diverse membership. However, these precautions likely helped some members to feel safer and more comfortable attending events.

The need to “sanitize” the content of materials aimed at promoting Tayf events and HIV prevention, even within the Center and in Tayf activities such as the Below the Belt groups, impeded the ability to use strategies such as eroticization and explicit descriptions of safer safe methods. In response, the Tayf Coordinators and Core Group developed coded terms and use of play on words (e.g., “cover its head, find peace for yours” to promote condom use) as a mean to convey sexual messaging safely. Nonetheless, it was challenging to publicize the existence of Tayf as a place to meet other young MSM, and address issues of importance among YMSM, which in turn may have diminished community engagement and the impact of the program on HIV prevention behavior and community empowerment. Further work is needed to identify publicity and marketing strategies that can mitigate security and privacy risks, and enable wider dissemination of messaging into the community, while still fostering a safe space for YMSM.

Regarding Tayf’s efficacy at promoting HIV prevention, one of our primary foci was HIV testing. HIV testing has steadily increased among MSM in Beirut over the past two decades. HIV testing used to be a highly stigmatized behavior in Lebanon [6], with only 25% of MSM in Beirut reporting to have ever been HIV-tested in 2009 [2]. Our prior research revealed a much higher rate of 63% among YMSM in 2012, although only 27% had recently (past six months) been HIV tested [27]. At enrollment in this study, 80% had ever tested and just under half had tested in the past six months. Consistent with this apparent temporal trend towards increased HIV testing in the community at the start of this study, our data revealed a significant increase in testing in our cohort over the course of the 30-month follow-up when not controlling for Tayf participation. Tayf participation was associated with higher rates of recent HIV testing rates when averaging rates across all timepoints; however, examination of change in testing over time revealed that the association of Tayf participation and greater testing diminished over the course of follow-up. It is conceivable that frequent periodic testing leads to a perception of less need for such frequent testing over time among some YMSM.

The other main focus of the study was condomless anal sex with partners whose HIV status was unknown or believed to be HIV-positive, as this context is associated with a higher risk for HIV transmission, especially given the rare use of (and limited access to) PrEP among study participants (and in Lebanon in general). A small minority (15%) of the sample reported any incidents of condomless anal sex with positive or unknown HIV status partners in the three months prior to baseline, and rates declined over the follow-up period in the overall cohort when controlling for Tayf participation. However, there was no apparent association between Tayf participation and the downward trend in this behavior over time. Given the low threshold of this crude binary measure (i.e., only one such condomless anal sex event resulted in being categorized as engaging in the risk behavior), it was important to examine more aspects of condomless anal sex. Accordingly, we examined the proportion of all reported condomless insertive and receptive anal sex events. The U-shaped distribution of data from these measures required that we transform these continuous measures into 3-level categorical variables, which still enabled a more nuanced analysis than the binary measure. Adjusting for Tayf participation, there was more condomless insertive anal sex over time in the sample, but no change in condomless receptive anal sex, and Tayf participation was not associated with either type of condomless anal sex. Unfortunately, these analyses did not account for the HIV status of the partner, as our assessment did not collect data on partner HIV status for each anal sex event.

There are several limitations to the results of this study. First, the lack of a control community (that received no intervention) or individual randomization to intervention participation (which was not possible due to contamination risks) hampered our ability to attribute observed changes to the intervention. For this reason, our findings are considered correlational and inferences of association with the intervention can be drawn, but not causal inferences. Second, the lack of randomization renders our data vulnerable to selection bias, especially given the stigmatized nature of the population. Indeed, participants in the study tended to be well educated, Lebanese, self-identified as gay and more open about their sexuality, and these same characteristics were associated with study retention and Tayf participation. Our statistical methods enabled us to control for these variables and limit the bias, but the external validity and generalizability of our findings remain compromised to the extent that bias was related to unobserved characteristics. Our measurement of Tayf participation enabled us to analyze the effects of Tayf, but this measurement was constrained by recall biases that could over or under report participation depending on accuracy of both memory and association of specific events as being implemented by Tayf. Further, our index of Tayf participation was based on assignment of more or less weight to specific types of Tayf activities; the weighting approached used was similar to prior published approaches [22], but alternative weighting decisions could have had different results. Other measurement limitations relate to reliance on self-report to assess HIV testing and condom use behavior, both of which could be influenced by memory recall and social desirability, although we sought to minimize the latter by offering participants the opportunity to self-administer the assessment.

In conclusion, this pilot of Tayf, a culturally adapted model of MP for YMSM in Beirut that included all of the core elements of MP with the exception of key aspects of Formal Outreach and Publicity, provides evidence of the feasibility and acceptability of this type of community-based HIV prevention and sexual health promotion program in an Arabic setting with a well-developed gay community. However, while the severe restrictions on publicity and marketing of program events and HIV prevention messaging, created by security and privacy risks, enabled the program to be feasible and safe for participants, these conditions likely limited the programs reach into the YMSM community and possibly its impact on HIV prevention behavior. Data from our research cohort of YMSM revealed that condom use during higher risk sex (with HIV-positive or unknown status partners) and recent HIV testing increased over time in the study sample, which could reflect positive health changes in the overall YMSM community—perhaps in part because of the presence of Tayf. However, our data did not provide any direct evidence that participation in Tayf was associated with these positive changes. Community-based programs such as Tayf appear to be a viable option for some Arabic settings, but further work is needed to explore how such programs can overcome environmental stigma and legal barriers in order to elicit more effective change in key sexual health and HIV prevention behaviors.

Data Availability

De-identified dataset is not available as participants did not consent to the use of data by researchers outside the study team.

References

UNAIDS, Middle East and North Africa Regional Report on AIDS, 2011. 2011.1. UNAIDS. Middle East and North Africa Regional Report on AIDS. UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2011.

Mumtaz G, Hilmi N, McFarland W, Kaplan RL, Akala FA, Semini I, et al. Are HIV epidemics among men who have sex with men emerging in the Middle East and North Africa?: a systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med. 2010;8(8):e1000444.

Heimer R, Barbour R, Khouri D, Crawford FW, Shebl F, Aaraj E, et al. HIV risk, prevalence, and access to care among men who have sex with men in Lebanon. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33(11):1149–54.

Ghanem CA, El Khoury C, Mutchler MG, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Kegeles S, Balan E, et al. Gay community integration as both a source of risk and resilience for HIV prevention in Beirut. Int J Behav Med. 2020;27(2):160–9.

Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(1):175–84.

McCormick J. Hairy Chest, Will Travel: Tourism, Identity, and Sexuality in the Levant. J Middle East Women’s Stud. 2011;7(3):71–97.

UNAIDS. Population mobility and AIDS. UNAIDS. AIDS & mobility. Geneva: 2001.

CDC. Risk Reduction Interventions: Men who have sex with men. 2012.

Kegeles SM, Rebchook G, Hays R, Pollack LM. Staving off increases in young gay/bisexual men's risk behavior in the HAART era. XIV International AIDS Conference; Barcelona, Spain: International AIDS Society; 2002.

Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Pollack LM, Coates TJ. Mobilizing young gay and bisexual men for HIV prevention: a two-community study. AIDS. 1999;13(13):1753–62.

Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment project: a community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(8):1129–36.

Cohen DA, Wu SY, Farley TA. Cost-effective allocation of government funds to prevent HIV infection. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(4):915–26.

Boushnak L, Boshnaq M. Coming out in Lebanon. New York Times. 2017.

Clark K, Pachankis J, Khoshnood K, Bränström R, Seal D, Khoury D, et al. Stigma, displacement stressors and psychiatric morbidity among displaced Syrian men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women: a cross-sectional study in Lebanon. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e046996.

Wagner GJ, Aunon FM, Kaplan RL, Karam R, Khouri D, Tohme J, et al. Sexual stigma, psychological well-being and social engagement among men who have sex with men in Beirut. Lebanon Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(5):570–82.

Mutchler MG, McDavitt BW, Tran TN, Khoury CE, Ballan E, Tohme J, et al. This is who we are: building community for HIV prevention with young gay and bisexual men in Beirut. Lebanon Cult Health Sex. 2018;20(6):690–703.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press; 1983.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992;111(3):455–74.

Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Penguin Books; 1972.

Rappaport J, Swift CF, Hess R. Studies in empowerment : steps toward understanding and action. New York: Haworth Press; 1984.

Zimmerman MA, Rappaport J. Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. Am J Community Psychol. 1988;16(5):725–50.

Shelley G, Williams W, Uhl G, Hoyte T, Eke A, Wright C, et al. An evaluation of Mpowerment on individual-level HIV risk behavior, testing, and psychosocial factors among young MSM of color: The monitoring and evaluation of MP (MEM) project. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29(1):24–37.

van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219–42.

Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–30.

Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. False-positive psychology: undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(11):1359–66.

Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. Hoboken: Wiley; 1999.

Wagner GJ, Tohme J, Hoover M, Frost S, Ober A, Khouri D, et al. HIV prevalence and demographic determinants of unprotected anal sex and HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Beirut. Lebanon Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(4):779–88.

Funding

The study was supported by funding from National Institute of Mental Health (Grant R01MH107272; PI: Wagner).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation were performed by GW, HG, ST, MM, EB, SC, SK. Data analyses were performed by BGD and GW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Wagner, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Lebanese American University and the Human Subjects Protection Committee at the RAND Corporation. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, G.J., Ghosh-Dastidar, B., Tebbetts, S. et al. A Pilot Evaluation of “Tayf”, a Cultural Adaptation of Mpowerment for Young Men who Have Sex with Men (YMSM) in Beirut, Lebanon, and Its Effects on Condomless Sex and HIV Testing. AIDS Behav 26, 639–650 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03424-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03424-4