Abstract

Violence experience has been consistently associated with HIV risks and substance use behaviors. Although many studies have focused on intimate partner violence (IPV), the role of violence at a structural level (i.e., police abuse) remains relevant for people who inject drugs. This study evaluated the association of IPV and police-perpetrated violence experiences with HIV risk behaviors and substance use in a cohort of HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Ukraine. We also evaluated possible moderation effects of gender and socioeconomic status in the links between violence exposure and HIV risk and polysubstance use behaviors. Data came from the Providence/Boston-CFAR-Ukraine Study involving 191 HIV-positive people who inject drugs conducted at seven addiction treatment facilities in Ukraine. Results from logistic regressions suggest that people who inject drugs and experienced IPV had higher odds of polysubstance use than those who did not experience IPV. Verbal violence and sexual violence perpetrated by police were associated with increased odds of inconsistent condom use. The odds of engaging in polysubstance use were lower for women in relation to police physical abuse. We found no evidence supporting socioeconomic status moderations. Violence experiences were associated with substance use and sexual HIV risk behaviors in this cohort of HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Trauma-informed prevention approaches that consider both individual and structural violence could improve this population’s HIV risks.

Resumen

La experiencia de violencia se ha asociado sistemáticamente con las conductas de riesgo para la adquisición o transmisión del VIH y con el uso de sustancias. Aunque muchos estudios se han centrado en la violencia infligida por la pareja íntima (VPI), el papel de la violencia estructural (es decir, el abuso policial) sigue siendo relevante para las personas que se inyectan drogas. Este estudio evaluó la asociación entre las experiencias de violencia perpetrada por la policía y la pareja íntima con los conductas de riesgo para la adquisición o transmisión del VIH y el uso de sustancias en una cohorte de personas VIH positivas que se inyectan drogas en Ucrania. También evaluamos los posibles efectos de moderación del género y el estatus socioeconómico entre la exposición a la violencia y los comportamientos de riesgo para la transmisión del VIH y uso de múltiples sustancias. Los datos provienen del estudio Providence / Boston-CFAR-Ucrania en el que participaron 191 personas infectadas por el VIH que se inyectan drogas, realizado en siete centros de tratamiento de adicciones en Ucrania. Los resultados de las regresiones logísticas sugieren que, en comparación con las personas que se inyectan drogas que no experimentaron IPV, las que experimentaron IPV tenían mayor probabilidad de uso de múltiples sustancias. La violencia sexual perpetrada por la policía se asoció con mayores probabilidades de un uso inconsistente del condón. No encontramos evidencia que apoye las moderaciones de género o estatus socioeconómico. Las experiencias de violencia se asociaron con el uso de sustancias y las conductas sexuales de riesgo para la transmisión del VIH en esta cohorte de personas VIH positivas que se inyectan drogas en Ucrania. Los enfoques de prevención basados en las experiencias traumáticas que tienen en cuenta tanto la violencia individual como la estructural podrían mejorar las conductas de riesgo para la transmission del VIH de esta población.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ukraine faces one of the fastest-growing HIV/AIDS epidemics in Europe [1]. An estimated 240,000 persons, about 1% of the adult population, live with HIV in Ukraine [2]. At 0.29 new HIV infections per 1000 uninfected people each year, it has the second-highest HIV incidence rate in Europe [3, 4]. Globally [5,6,7] and in Ukraine [8], HIV transmission disproportionately occurs among key populations, particularly people who inject drugs and their sex partners. Unsafe drug use [9] and sexual transmission [7, 10] are two primary routes of HIV transmission in Eastern Europe in this population, underscoring the importance of identifying correlates of these two HIV risk categories to disrupt further spread of HIV.

Violence Exposure as a Factor for HIV Risk Behaviors

The risk environment framework [11] suggests that interpersonal and broader socioenvironmental contexts generate barriers to and facilitators of individual HIV risk behaviors [12,13,14,15]. Violence exposure, such as intimate partner violence (IPV), may represent a key risk factor embedded in social contexts that shape individuals’ HIV risk behaviors. IPV refers to physical, sexual, and psychological aggression and abuse that intimidates or controls another in an intimate relationship [16, 17]. Problematic substance use behaviors have been frequently reported as a maladaptive coping mechanism in response to distress associated with IPV exposure [18, 19]. Consistently, higher rates of unhealthy alcohol use and unsafe substance use, such as binge drinking in the general population [18, 20] and the use of contaminated needles among people who inject drugs [21], have been reported among IPV survivors compared to those without IPV exposure. Similarly, IPV survivors may have less control over sexual activities and be less empowered to promote healthy sexual practices [22], such as negotiating condom use with partners [18]. Consistently, IPV exposure has been linked to increased sex risk behaviors in general populations [23].

Importantly, from an ecological perspective [24], violence at a structural level can contribute to the HIV risk environment [11, 25], particularly among people who inject drugs. Violence at a structural level refers to the socioenvironmental context that is beyond individuals’ direct control such as police violence [11, 25]. Studies from Eastern Europe have documented that people who inject drugs frequently encounter punitive police practices [26], including physical, verbal, and sexual violence [27,28,29]. The prevalence of police violence is elevated in Ukraine, triggered by overall socioeconomic instability and its induced aggression, violence, and war in the region [30]. Consistent with findings from studies in Eastern Europe [26], police violence disproportionately affects people who inject drugs, particularly those who are HIV positive in Ukraine. They are often confronted with police violence on their way to or from service venues, including syringe-exchange sites, pharmacies legally selling sterile injection equipment [31], and HIV and addiction clinics [25, 32, 33]. In an earlier study of people who inject drugs in Odesa, Ukraine, 86% reported coercive experiences with police, including paying police to avoid arrest and being threatened by police to provide information on other people who inject drugs [29]. Another study showed that 58.5% of HIV-positive people who were recently released from prison have been detained without charges and 85.2% of those in addiction care clinics were detained on their way to or from a care site in Ukraine [32].

As is the case with exposure to IPV, experiences or expectations of police violence may generate substantial distress among violence survivors, which may trigger substance use and sexual risk behaviors. Empirical studies have consistently reported that police violence is associated with increased rates of binge drinking [34], needle sharing [28], and inconsistent condom use or coercion into unprotected sex [35, 36]. However, limited recent data are available concerning the potential role of IPV and police violence in HIV risk behaviors and polysubstance use among people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Polysubstance use, the concurrent or sequential use of more than one drug or type of drug [37], is particularly relevant to HIV harm reduction efforts among people who inject drugs, considering that polysubstance use has been associated with adverse outcomes regarding the treatment of substance use disorders [38, 39] and with sexual risk behaviors [40].

Moderating Effects: Socioeconomic Status and Gender

Holding a social status of less power and fewer resources in a given society may exacerbate the association between violence exposure and HIV risk behaviors [41]. Gender and socioeconomic status (SES), for example, fundamentally shape the probability of risk exposure of any type [42,43,44]. Further, consequences of exposure might be worse for those who hold less privileged status, because access to personal and social resources are often structured unfavorably for those who hold a less privileged position in these two potent social status markers [45,46,47,48].

Consistently, empirical studies have reported that female gender and lower economic resources are associated with elevated violence exposure and vulnerability globally [49, 50] and in this region [51]. In Ukraine, 33% of women experience IPV, compared to 23% of men [52]. Similarly, in Ukraine, sexual violence perpetrated by police almost exclusively affects women who inject drugs (13.1% vs. 1.4% of their male counterparts) [53]. Further, women may suffer more consequences subsequent to violence exposure [41], as evidenced by increased rates of alcohol use disorders [54] and marijuana use [55] than male IPV survivors. Similarly, violence survival has been recognized as a critical factor for HIV risks, particularly among women [56, 57]. As such, it is plausible that associations of violence with HIV risk and its related problematic substance use might be more evident among HIV-positive women who inject drugs than their male counterparts. Gender differences may emerge even more prominently in cultural contexts that hold strong patriarchal values at a societal level, such as Ukraine [58, 59].

SES might be another moderator of differential risk exposures and vulnerability for HIV-positive people who inject drugs. Food insecurity or living in poverty may function as an additional source of distress and risk for HIV-positive people who inject drugs [60]. With limited disposable economic resources among those with lower income, substance use may represent an option to cope with economic distress [61,62,63]. Moreover, economic vulnerability among IPV survivors with low SES may increase economic dependence on their abusive partners [64] and further decrease negotiation power and control over sexual practices [65]. Possible contributions of SES to the linkage between violence and HIV risk behaviors might be particularly relevant to Ukraine, which has experienced drastic economic disruption and uncertainty [66].

Current Study

Few data from Ukraine are available on the relationships among IPV, police violence, HIV risk behaviors, and polysubstance use among HIV-positive people who inject drugs or the possible roles of gender and SES in these associations. To address these research gaps, the current study addressed the following research aims:

-

(1) To assess the association of IPV and police violence with HIV risk behaviors (i.e., recent injection drug use and inconsistent condom use) and polysubstance use.

-

(2) To explore female gender and low SES as potential moderators of the relation between violence exposure and HIV risk behaviors and polysubstance use.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, Participants, and Procedures

The Providence/Boston-CFAR-Ukraine study consecutively recruited and enrolled 191 HIV-positive people who inject drugs from July through September 2017 at seven health care facilities in six regions of Ukraine, including three facilities providing opioid agonist therapy only (two sites in the Kyiv region and one in the Mykolaiv region) and four facilities providing colocated opioid agonist therapy and HIV treatment services (in the Dnipro, Lviv, Odesa, and Cherkasy regions). Of note, possible site differences by the type of care provision (i.e., addiction treatment only vs. addiction treatment with colocated HIV care) were evaluated in a prior study and no systematic site differences were found [67]. An on-site research assistant screened patients referred by their health provider for eligibility, invited eligible patients to enroll in the study, obtained informed consent, and administered a face-to-face interview using Research Electronic Data Capture in a private and confidential location at the clinics. Eligibility criteria included: (a) 18 years or older; (b) lifetime history of injecting drugs; (c) HIV-positive status; (d) currently receiving opioid agonist treatment; (e) fluent in Russian or Ukrainian; and (f) able to provide informed consent. Researchers initially approached 198 potential participants. Of the 198 people, 191 met the eligibility criteria and agreed to participate in the study. Survey measures were administered in either Russian or Ukrainian, depending on participants’ preference. Participants received 200 Ukrainian hryvnia ($8 U.S. dollars at the time of the study) in cash as compensation for their time and transportation costs. Further details on the study design, study sites, and sampling procedures can be found elsewhere [67]. The institutional review boards at the affiliated institutes approved all study procedures.

Measures

Outcome Measures

Polysubstance Use

This measure [68, 69] was based on three dichotomized items assessing past-30-day injection substance use [heroin, opioids (codeine, street methadone, krokodil, shirka), or heroin mixed with stimulants (crack)]; past-12-month risky drinking (AUDIT-C score above four for men and above three for women); and current cigarette use. We summed the resultant dichotomous outcomes into a composite variable and defined use of more than two types as polysubstance use.

HIV Risk Behaviors

HIV risk behaviors were measured with two items [68, 69], recent injection drug use and inconsistent condom use. Injection drug use was assessed as number of days of reported injection drug use in the past 30 days (i.e., at least 1 day). Inconsistent condom use was assessed as having any sex without a condom in the past 12 months.

Predictors

Intimate Partner Violence

IPV was measured with three dichotomized items [70]: “In the past 12 months, has a partner threatened you with violence, pushed or shoved you, or thrown something at you that could hurt?”; “Have you had an injury, such as a sprain, bruise, or cut because of a fight with a partner?”; and “Has a partner insisted on or made you have sexual relations with him/her when you didn’t want to?” Any positive response was considered as having IPV experience.

Police Verbal Violence

We assessed lifetime experience of verbal violence from police [71] with one item: “Has a police officer verbally abused you?” Any positive response was considered as experiencing police verbal violence.

Police Physical Violence

Lifetime police physical violence was measured with one item: “Have you been beaten by a police officer?” Any positive response was considered as experiencing police physical violence.

Police Sexual Abuse

Lifetime experience of sexual abuse perpetrated by police [71] was assessed with two items: “Have you ever been forced to have sex with a police officer?” and “Have you been forced by a police officer to have sex with other people?” Any positive response was considered as having police sexual abuse exposure.

Moderators

Moderators included gender and per capita household income dichotomized at the sample median income (1,666 Ukrainian hryvnia) as a proxy variable for SES.

Covariates

Covariates in each model included age in years (M = 39.96, SD = 6.93). For the model predicting HIV risk behavior (i.e., injecting drugs or inconsistent condom use), we added the covariates of past-12-month risky drinking, assessed using AUDIT-C.

Analysis

We used logistic regression for models with dichotomous outcome variables. First, to evaluate the association of IPV, police verbal or physical violence, and police sexual violence with polydrug use and HIV risks, three logistic regressions were estimated for each outcome measure. Second, we evaluated possible gender moderation by testing interaction terms between gender and each violence measure (i.e., IPV × gender; police verbal or physical violence × gender; and police sexual violence × gender). Finally, we evaluated possible SES moderation by testing interaction terms between income and each violence measure. All covariates were included in each model. For the HIV risk behavior variables, risky drinking was added as a covariate. We conducted all analyses using SPSS version 25.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics. In this sample, about three fourths of participants were male, reflecting the demographics of people who inject drugs in Ukraine. About one third reported using more than two drugs in the past 12 months, and more than half were engaged in HIV risk behaviors by either injecting drugs or inconsistently using condoms. Approximately 14% of both men and women experienced IPV. Most participants in this sample reported experiencing verbal (83.2%) or physical (77.4%) violence from police. Police sexual violence was almost exclusively reported by women.

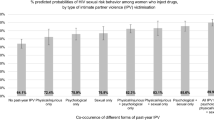

Violence Exposure, Polysubstance Use, and HIV Risk Behaviors

Models 1, 4, and 7 focused on the main effect of IPV and police violence on outcome measures (Table 2). Compared to people who experienced no IPV, those who experienced IPV had almost three times higher odds of using more than two drugs (AOR 2.74, 95% CI 1.15, 6.51). IPV was not associated with HIV risk behaviors (i.e., injecting drugs or inconsistent condom use). Police verbal abuse was associated with inconsistent condom use (OR 2.71, 95% CI 1.10, 6.70). Sexual violence from police was associated with an almost sixfold increase in odds of inconsistent condom use (OR 5.88, 95% CI 1.23, 28.09).

Gender and SES Moderation

We assessed whether female gender and lower income moderated the detrimental impacts of violence exposure on outcome measures. We evaluated gender interaction terms first (Table 2, Model 2 for polysubstance use, Model 5 for injecting drugs, and Model 8 for inconsistent condom use). Next, income interaction terms were evaluated (Table 2, Model 3 for polysubstance use, Model 6 for injecting drugs, and Model 9 for inconsistent condom use). Gender differences emerged in relation to polysubstance use. The odds of engaging in polysubstance use were lower for women in relation to police physical abuse (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.07, 0.96). We found no evidence for SES differences.

Discussion

The current study evaluated the extent to which IPV and police violence experiences were associated with HIV risk behaviors—namely, injection drug use, unprotected sex, and polysubstance use. We also explored potential gender and SES differences in these associations.

Consistent with prior studies of violence and substance use in other contexts [18, 20, 21], this study’s findings suggest that IPV experience is associated with increased odds of polysubstance use among HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Major stressors such as IPV may increase reliance on substance use for immediate relief to cope with distress triggered by IPV [18]. More adaptive options to address distress associated with IPV, such as seeking professional counseling or support from family and friends, might be perceived as financially expensive or socially challenging [72]. HIV-positive people who inject drugs have two highly stigmatized characteristics—substance use [73] and HIV-positive status [74]. Because HIV-positive people who inject drugs live at the intersection of these stigmata [67], they might be less likely to disclose their experience of IPV, another socially stigmatized experience [75], to others to seek help. Particularly, when IPV survivors live in a society with a more permissive attitude toward IPV, as seems the case in Ukraine [76], seeking professional counseling or support from families and friends can be challenging. Exploring intersectional stigma as a possible mechanism linking IPV and substance use might advance our understanding of the association between IPV and polysubstance use.

The current findings also suggest that police violence is associated with HIV risk behaviors, especially inconsistent condom use and polysubstance use. This study confirmed that sexual violence perpetrated by police in Ukraine primarily affects women who inject drugs (25% vs. 0.7% of men) [53]. This study’s findings are also in line with prior studies reporting heightened sexual risk behaviors among those exposed to police violence [34,35,36, 77]. The police’s authority to arrest people who inject drugs creates inequity in power that makes people who inject drugs vulnerable to various forms of abuse, including sexual violence. Experiencing sexual violence in such fundamentally power-imbalanced interactions may increase disempowerment and helplessness among violence survivors [27], which can further compromise their negotiation capacity with sexual partners regarding protective sexual practices [18, 22].

In this cohort, neither IPV nor police violence measures were associated with injection drug use, suggesting that violence exposure might be a particularly important risk factor for polysubstance use and inconsistent condom use. However, our violence measure only assessed any lifetime exposure to violence rather than severity or frequency. Because police violence against people who inject drugs, for example, is particularly prevalent, measures of any lifetime experience may need to be revisited. Rather, probing diverse dimensions of police violence exposure, such as timing, frequency, severity, or accumulation of exposure over time, may be a fruitful direction in future studies to further clarify the role of violence in injection drug use in this specific population in Ukraine.

We found evidence for gender moderation in the association of police physical violence with polysubstance use. Moderation analyses could identify subgroups of HIV-positive people who inject drugs, had violence exposure, and have particularly heightened vulnerabilities to polysubstance use and HIV transmission-related risk behaviors. In contrast to prior studies documenting heightened alcohol use disorders [54] or marijuana use [55] among female IPV survivors relative to male survivors, in this cohort, men who had experienced police physical violence had higher odds of polysubstance use. These findings may provide support for the gender socialization hypothesis [78] and gendered-strain theory [79], which postulate that women’s maladjustment profiles tend to take an inward format (e.g., depression) rather than outward format (e.g., substance use), because externalizing behavior problems, such as substance use, are not aligned with gendered behavioral norms. Possible influences of gendered behavioral norms might be more prominent in cultural contexts where traditional gendered norms are strongly held at a societal level, such as Ukraine [58, 59].

Alternatively, our findings might be due to inadequate representation of women. Although this study reflects the gender distribution of people who inject drugs in Ukraine, women were relatively less represented in our study sample (n = 48; 25.1%), which is different than studies reporting worse consequences of violence exposure for women—those studies had either similar representation across genders [55] or overrepresentation of women [54]. Further, IPV, widely known to be higher among women in Ukraine [52], was higher among men in this cohort, which was unexpected. Relatedly, our analyses of sexual violence perpetrated by police, which disproportionately affected women in this cohort and other settings [53], were limited by the smaller number of female participants, likely contributing to a very large confidence interval associated with police sexual violence. Because women are more likely to be exposed to IPV [52] and sexual police violence [53, 80,81,82], oversampling HIV-positive women who inject drugs and having a gender-balanced sample could further explicate these issues in cultural contexts such as Ukraine, where an IPV-permissive attitude toward women remains pervasive [58, 59].

We found no evidence for income moderation. The study’s findings suggest that IPV victimization and police sexual violence might equally affect HIV-transmission behaviors regardless of income level. As such, intervention strategies in Ukraine may need to involve HIV-positive people who inject drugs across varying income levels.

Our study findings should be contextualized in light of their methodological limitations. First, this study used cross-sectional data, limiting our ability to rule out reverse causality. Prospectively evaluating violence exposure and its temporality in determining HIV risks will further clarify the role of violence. Specifically, a longitudinal framework can open an opportunity to evaluate joint and unique impacts of violence in varying developmental epochs. Childhood violence exposure—for example, child abuse—has been associated with increased substance use [83, 84] and risky HIV sexual behaviors [84, 85], and seems to intersect with IPV exposure during adulthood to increase the risk of unhealthy alcohol use [86]. Second, self-report surveys may introduce social desirability bias, due to the sensitive nature of and stigma associated with drug use and sex risk behaviors. Third, the clinic-based convenience sampling approach limited sample representativeness. Fourth, our polysubstance use measure specifically focused on the two most prevalent legal substances and those typically administered via injection, considering the importance of this type of substance administration among people who inject drugs. Expanding the measure of polysubstance use might be a fruitful future direction to advance our understanding of complex substance use behaviors among people who inject drugs. Fifth, due to the overall limited sample size, we evaluated each violence measure separately, rather than including all measures in one model. With our current modeling strategy, we couldn’t delineate a unique association of each violence measure with polysubstance use and HIV risk behaviors. To address this concern, we estimated associations among the three violence measures (i.e., IPV and police verbal or physical abuse, IPV and police sexual abuse, and police verbal or physical abuse and police sexual abuse). None of the phi coefficients was statistically significant, suggesting no substantial overlap in associations between the three violence measures. Finally, we examined possible gender and SES moderation effects separately, but could not explore the potential intersectionality of gender with SES. People typically identify with multiple categories of social disadvantage (e.g., low SES and female gender). A better understanding of the intersection of multiple socially disadvantaged statuses [87] could add to the analysis of violence exposure and HIV risk behaviors.

Conclusions

This study adds the following conclusions to the existing literature on violence and HIV risk. First, it focused on HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Ukraine and thus, provides empirical evidence supporting the risk environment framework [11] and ecological perspective [24] in prevention efforts to disrupt further spread from this high-risk group to the general population. Second, this study focused on polysubstance use, which is particularly relevant to people who inject drugs [38, 39], and their HIV risks, such as sexual risk behaviors [40]. Third, we tested gender and SES differences to further clarify the linkage between violence exposure and HIV risk transmission-related behaviors.

In conclusion, this study’s findings support the link between violence experiences at both individual and structural levels with HIV risks among HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Consistent with prior studies [13, 88], our study findings might imply that the risk environment, specifically IPV and police sexual violence, is linked to HIV transmission from key populations and their sex partners to the general population in Ukraine. Consequently, efforts targeting this key population should aim to create enabling [89] or structural [90] HIV prevention strategies that account for social and environmental contexts that HIV-positive people face [12,13,14]. Primary prevention strategies to reduce IPV and police sexual violence [13, 88] could include public education regarding IPV to counter permissive attitudes toward IPV in Ukraine [81]. Further, police training with a focus on HIV prevention and occupational safety needs to be implemented for the benefit of people who inject drugs [91] and to increase police perpetrators’ awareness of victims’ traumatization and HIV risks [92, 93]. Relatedly, the globally and regionally pervasive stigma regarding substance use leads police to perceive people who inject drugs as potential criminals [94] and fuels a punitive policing approach to limiting drug use [95]. As such, coupled with effective police training, public health messaging about drug use as a chronic health condition [96] may be useful to improve attitudes of the general public and police together [97] and reduce police violence in Ukraine. Further, this study’s findings indicate the need for trauma-informed HIV prevention. Routine screening for interpersonal and structural violence experiences of HIV-positive people who inject drugs could increase health professionals’ understanding of their risk environment and help providers further tailor needed mental health services for violence survivors. Taken together, a multipronged trauma-informed approach has the potential to reduce risks among HIV-positive people who inject drugs and protect their human rights.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to our compliance with the IRB regulations for the current study but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Altice FL, Azbel L, Stone J, et al. The perfect storm: incarceration and the high-risk environment perpetuating transmission of HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Lancet. 2016;388(10050):1228–48.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Ukraine: HIV and AIDS estimates. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2016.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2018–2017 data. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019.

Frank TD, Carter A, Jahagirdar D, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2017, and forecasts to 2030, for 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(12):E831–59.

Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49.

Kruglov Y, Kobyshcha Y, Salyuk T, Varetska O, Shakarishvili A, Saldanha V. The most severe HIV epidemic in Europe: Ukraine’s national HIV prevalence estimates for 2007. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(suppl 1):i37-41.

UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010.

KuzinMartzynovskaAntonenko IVZ. HIV infection in Ukraine. Kyiv: Public Health Center of the Minority of Health; 2019.

Goliusov AT, Dementyeva LA, Ladnaya NN, Pshenichnaya VA. Country progress report of the Russian Federation on the implementation of the declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS. Moscow: Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation; 2010.

Pylypchuk R, Marston C. Factors associated with sexual risk behaviour among young people in Ukraine. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2009;16(4):165–74.

Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13(2):85–94.

Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):59–72.

Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(5):1026–44.

Rothenberg R, Baldwin J, Trotter R, Muth S. The risk environment for HIV transmission: results from the Atlanta and Flagstaff network studies. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):419–32.

Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–9.

Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health. 2011;20(7):991–1006.

Rutter M. Pathways from childhood to adult life. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1989;30(1):23–51.

Zahnd E, Aydin M, Grant D, Holtby S. The link between intimate partner violence, substance abuse and mental health in California. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011.

Braitstein P, Li K, Tyndall M, et al. Sexual violence among a cohort of injection drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(3):561–9.

World Health Organization. Violence against women and HIV/AIDS: critical intersections. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):149–77.

Bronfrenbrenner U. Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005.

Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Dvoryak S, Reisner SL, Needle R, Woody G. “We fear the police, and the police fear us”: structural and individual barriers and facilitators to HIV medication adherence among injection drug users in Kiev, Ukraine. AIDS Care. 2010;22(11):1305–13.

Mazhnaya A, Bojko MJ, Marcus R, et al. In their own voices: breaking the vicious cycle of addiction, treatment and criminal justice among people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2016;23(2):163–75.

Lunze K, Lunze FI, Raj A, Samet JH. Stigma and human rights abuses against people who inject drugs in Russia: a qualitative investigation to inform policy and public health strategies. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136030.

Lunze K, Raj A, Cheng DM, et al. Punitive policing and associated substance use risks among HIV-positive people in Russia who inject drugs. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):19043.

Booth RE, Dvoryak S, Sung-Joon M, et al. Law enforcement practices associated with HIV infection among injection drug users in Odessa, Ukraine. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2604–14.

Kozyreva O, Sagaidak-Nikituk R, Demchenko N. Analysis of the socio-economic development of Ukrainian regions. Balt J Econ Stud. 2017;3(2):51–8.

Spicer N, Bogdan D, Brugha R, Harmer A, Murzalieva G, Semigina T. ‘It’s risky to walk in the city with syringes’: understanding access to HIV/AIDS services for injecting drug users in the former Soviet Union countries of Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan. Global Health. 2011;7:22.

Izenberg JM, Bachireddy C, Soule M, Kiriazova T, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. High rates of police detention among recently released HIV-infected prisoners in Ukraine: implications for health outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):154–60.

Judice N, Zaglada O, Mbuya-Brown R. HIV policy assessment: Ukraine. Washington: USAID; 2011.

Odinokova V, Rusakova M, Urada LA, Silverman JG, Raj A. Police sexual coercion and its association with risky sex work and substance use behaviors among female sex workers in St. Petersburg and Orenburg, Russia. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):96–104.

Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women, drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:S16-21.

Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Pretorius C, et al. Estimating the impact of reducing violence against female sex workers on HIV epidemics in Kenya and Ukraine: a policy modeling exercise. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69:122–32.

Schensul JJ, Convey M, Burkholder G. Challenges in measuring concurrency, agency and intentionality in polydrug research. Addict Behav. 2005;30(3):571–4.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Polydrug use: patterns and responses. Lisbon: EMCDDA; 2009.

Tavitian-Exley I, Vickerman P, Bastos FI, Boily MC. Influence of different drugs on HIV risk in people who inject: systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2015;110(4):572–84.

Tavitian-Exley I, Boily MC, Heimer R, Uuskula A, Levina O, Maheu-Giroux M. Polydrug use and heterogeneity in HIV risk among people who inject drugs in Estonia and Russia: a latent class analysis. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1329–40.

Caldwell JE, Swan SC, Woodbrown VD. Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychol Violence. 2012;2(1):42–57.

Adler NE, Rehkopf DHUS. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29(1):235–52.

Aneshensel CS, Rutter CM, Lachenbruch PA. Social structure, stress, and mental health: competing conceptual and analytic models. Am Sociol Rev. 1991;56(2):166–78.

Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1989;30(3):241–56.

Aneshensel CS. Toward explaining mental health disparities. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(4):377–94.

Pearlin LI, Bierman A. Current issues and future directions in research into the stress process. In: Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. p. 325–40.

Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Creatore MI, Gozdyra P, Glazier RH. Urban neighborhoods, chronic stress, gender and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(10):2604–16.

Yu D, Peterson NA, Sheffer MA, Reid RJ, Schnieder JE. Tobacco outlet density and demographics: analysing the relationships with a spatial regression approach. Public Health. 2010;124(7):412–6.

World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Laflamme L, Burrows S, Hasselberg M. Socioeconomic differences in injury risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Survey on violence against women: well-being and safety of women. Helsinki: Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe; 2019.

United Nations Development Programme. Ten unknown facts about domestic violence in Ukraine: a joint EU/UNDP Project releases new poll results. Kyiv: United Nations Development Programme; 2010.

Kutsa O, Marcus R, Bojko MJ, et al. Factors associated with physical and sexual violence by police among people who inject drugs in Ukraine: implications for retention on opioid agonist therapy. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:20897.

Anderson KL. Perpetrator or victim? relationships between intimate partner violence and well-being. J Marriage Fam. 2002;64(4):851–63.

Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Clinically abusive relationships in an unselected birth cohort: men’s and women’s participation and developmental antecedents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113(2):258–70.

Dunkle KL, Jewkes R. Effective HIV prevention requires gender-transformative work with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(3):173–4.

Silverman JG, Decker MR, Kapur NA, Gupta J, Raj A. Violence against wives, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection among Bangladeshi men. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(3):211–5.

Yakushko O. Ambivalent sexism and relationship patterns among women and men in Ukraine. Sex Roles. 2005;52(9–10):589–96.

Maume DJ, Hewitt B, Ruppanner L. Gender equality and restless sleep among partnered Europeans. J Marriage Fam. 2018;80(4):1040–58.

Idrisov B, Lunze K, Cheng D, Blokhina E, Gnatienko N, Patts G, et al. Food insecurity, HIV disease progression and access to care among HIV-infected Russians not on ART. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(12):3486–95.

Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990–2010). Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(1):4–27.

Mossakowski KN. Is the duration of poverty and unemployment a risk factor for heavy drinking? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(6):947–55.

Lee JO, Hill KG, Hartigan LA, et al. Unemployment and substance use problems among young adults: does childhood low socioeconomic status exacerbate the effect? Soc Sci Med. 2015;143:36–44.

Moreno CL. The relationship between culture, gender, structural factors, abuse, trauma, and HIV/AIDS for Latinas. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(3):340–52.

Jewkes RK, Levin JB, Penn-Kekana LA. Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(1):125–34.

O’Leary KD, Tintle N, Bromet EJ, Gluzman SF. Descriptive epidemiology of intimate partner aggression in Ukraine. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(8):619–26.

Sereda Y, Kiriazova T, Makarenko O, et al. Intersectional stigma and quality of care for HIV-positive people in addiction treatment in Ukraine. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(5):e25492.

Weatherby NL, Needle R, Cesari H, et al. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Eval Program Plann. 1994;17(4):347–55.

Needle R, Fisher D, Weatherby N, Chitwood D. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav. 1995;9(4):242–50.

Silverman JG, Raj A, Cheng DM, et al. Sex trafficking and initiation-related violence, alcohol use, and HIV risk among HIV-infected female sex workers in Mumbai. India J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S1229–34.

Booth RE, Kennedy J, Brewster T, Semerik O. Drug injectors and dealers in Odessa. Ukraine J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(4):419–26.

Weissbecker I, Khan O, Kondalova N, Poole L, Cohen JT. Mental health in transition: assessment and guidance for strengthening integration of mental health into primary health care and community-based service platforms in Ukraine. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2017.

Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, Hasin DS. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(5):378–88.

Mahajan J, Sayles V, Patel R, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22:S67–79.

Overstreet NM, Quinn DM. The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;35(1):109–22.

Tran TD, Nguyen H, Fisher J. Attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women among women and men in 39 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0167438.

Lunze K, Raj A, Cheng DM, et al. Sexual violence from police and HIV risk behaviours among HIV-positive women who inject drugs in St Petersburg, Russia: a mixed methods study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(4):20877.

Chodorow N. Mothering, object-relations, and the female Oedipal configuration. Fem Stud. 1978;4(1):137–58.

Broidy L, Agnew R. Gender and crime: a general strain theory perspective. J Res Crime Delinq. 1997;34(3):275–306.

Sarang A, Rhodes T, Sheon N, Page K. Policing drug users in Russia: risk, fear, and structural violence. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(6):813.

Cottler LB, O’Leary CC, Nickel KB, Reingle JM, Isom D. Breaking the blue wall of silence: risk factors for experiencing police sexual misconduct among female offenders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):338–44.

Network EHR. Women and drug policy in Eurasia. Vilnius: EHRN; 2010.

Banducci AN, Hoffman EM, Lejuez CW, Koenen KC. The impact of childhood abuse on inpatient substance users: specific links with risky sex, aggression, and emotion dysregulation. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(5):928–38.

Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high-risk behaviors, and morbidity in adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(3):344–52.

Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: a 30-year follow-up. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):149–58.

Grest CV, Cederbaum JA, Lee D, Lee JO. Adverse childhood experiences, intimate partner violence, and alcohol use among college students. J Interpers Violence. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520913212.

Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality–an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–73.

Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):268–84.

Tawil O, Verster A, O’Reilly KR. Enabling approaches for HIV/AIDS prevention: can we modify the environment and minimize the risk? AIDS. 1995;9(12):1299–306.

Des Jarlais DC. Structural interventions to reduce HIV transmission among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2000;14:S41–6.

El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA, El Sadr WM. HIV and people who use drugs in central Asia: confronting the perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(0–1):S2-6.

Beletsky L, Grau L, White E, Bowman S, Heimer R. Prevalence, characteristics, and predictors of police training initiatives by US SEPs: building an evidence base for structural interventions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(1–2):145–9.

Beletsky L, Thomas R, Shumskaya N, Artamonova I, Smelyanskaya M. Police education as a component of national HIV response: lessons from Kyrgyzstan. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:S48-52.

Rhodes T, Platt L, Sarang A, Vlasov A, Mikhailova L, Monaghan G. Street policing, injecting drug use and harm reduction in a Russian city: a qualitative study of police perspectives. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):911–25.

Nebrenchina L. Drug policy in Russia. Moscow: Andrey Rylkov Foundation for Health and Social Justice; 2009.

Bahora M, Hanafi S, Chien V, Compton M. Preliminary evidence of effects of crisis intervention team training on self-efficacy and social distance. Admin Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2008;35(3):159–67.

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(1):39–50.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to an associate professor of medicine at Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Dr. Daniel Fuster, MD, PhD, for his help with translating the abstract into Spanish. We would also like to extend our gratitude to study participants for their contribution to the study.

Funding

This study was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant No. P30AI042853) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant Nos. K99DA041245, R00DA041245, and a NIDA INVEST fellowship). The funding agencies played no role in any aspects of the current study, including the design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of the study and the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JOL originated the study, guided data analyses, led the writing of the article, and coordinated drafting of the manuscript among co-authors; YY finalized the literature review, conducted analyses, and drafted the method and result sections, including tables; BI contributed to the data collection, organized the database, and contributed to the analysis framework; TK, OM, YS, and SB designed and led implementation of data collection and management; KC conducted the literature search with a focus on intimate partner violence and outcome measures; SFS conducted the literature search with a focus on police violence and outcome measures; PSN, NH, TF, JHS, and JL contributed to the interpretation of the study findings and provided important intellectual input; KL contributed to the conceptualization of the study, secured the funding, led the data collection, and contributed to the interpretation of findings. In addition, all authors have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study procedures for the current study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the affiliated institutes, Boston Medical Center, and the Ukrainian Institute on Public Health Policy.

Informed Consent

All study participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.O., Yoon, Y., Idrisov, B. et al. Violence, HIV Risks, and Polysubstance Use Among HIV-Positive People Who Inject Drugs in Ukraine. AIDS Behav 25, 2120–2130 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03142-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03142-3