Abstract

We conducted a novel pilot randomized controlled trial of the Treatment Ambassador Program (TAP), an 8-session, peer-based, behavioral intervention for people with HIV (PWH) in South Africa not on antiretroviral therapy (ART). PWH (43 intervention, 41 controls) completed baseline, 3- and 6-month assessments. TAP was highly feasible (90% completion), with peer counselors demonstrating good intervention fidelity. Post-intervention interviews showed high acceptability of TAP and counselors, who supported autonomy, assisted with clinical navigation, and provided psychosocial support. Intention-to-treat analyses indicated increased ART initiation by 3 months in the intervention vs. control arm (12.2% [5/41] vs. 2.3% [1/43], Fisher exact p-value = 0.105; Cohen’s h = 0.41). Among those previously on ART (off for > 6 months), 33.3% initiated ART by 3 months in the intervention vs. 14.3% in the control arm (Cohen’s h = 0.45). Results suggest that TAP was highly acceptable and feasible among PWH not on ART.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

South Africa currently provides treatment for nearly 60% of the 7.9 million people with HIV (PWH) in the country. While this is over a two-fold increase in the past decade [1], it is still far from achieving UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets [2]. Significant attrition from the care cascade has been documented consistently throughout the region, despite sweeping changes made to increase access to and availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) [3,4,5,6,7]. A recent prospective cohort study of 500 PWH presenting for testing in Soweto and Gugulethu townships adds to these data, showing that 62% of treatment-eligible PWH initiated ART, but only 25% had evidence of an undetectable HIV-1 plasma RNA (< 50 copies/ml) within 9 months of testing [8, 9].

Prior research has shown PWH encounter individual, social, and structural barriers to initiating care, such as fear of side effects, HIV-associated stigma, and long clinic waiting times [10]. For those who delay or decline treatment, the perceived risks of disclosing one’s status and experiencing HIV-associated stigma may outweigh the life-saving benefits of ART [11]. Conversely, those who start treatment and achieve viral suppression do so through a combination of adaptive coping and support from key partners. These findings are consistent with other studies showing that PWH who have non-judgmental, nonconfrontational support are more likely to be engaged in care [12, 13].

While prior research has focused on how to better engage individuals who fail to initiate ART, few studies have developed interventions targeting individuals who were previously on ART but discontinued treatment [7, 10]. Differentiated service delivery models, client-centered approaches that simplify and adapt HIV services to reflect the preferences, expectations, and needs of individual PWH, while reducing unnecessary burdens on the healthcare system, are critical in engaging this population in care [8, 14, 15]. Behavioral research can inform the feasibility and acceptability of differentiated care models for optimizing ART initiation and adherence. In particular, research focused on increasing resilience, or individuals’ capacity to overcome adversity and stress to achieve health and well-being [16,17,18], may be especially helpful for identifying modifiable strength-based factors that can promote healthy outcomes [11, 19, 20].

Interventions promoting adaptive coping may be associated with acceptance of a new HIV diagnosis by fostering problem solving and emotional expression, while mitigating the perceived risk associated with starting treatment [7, 21]. In addition, enhancing social support, including comfort and/or assistance from others, has been shown to be associated with better HIV-related health symptoms among PWH, possibly because it buffers people from the negative effects of stressors on physical health [19, 20]. For this reason, peer-delivered interventions may be successful in improving engagement in care for PWH by increasing levels of social support as well as providing patients with information on how to best navigate HIV-services [12, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

In this study, we developed and tested a new intervention, called the “Treatment Ambassador Program (TAP),” a client-focused, peer-based differentiated care strategy for addressing individual, social, and structural level barriers to ART initiation, in order to promote early and enduring treatment uptake by PWH [29,30,31]. Given its focus on reducing individual barriers to starting ART, promoting social support, and enhancing linkages to the healthcare system, we hypothesized that the Treatment Ambassador Program would be highly acceptable and feasible among PWH who faced challenges initiating or staying on ART in South Africa [32, 33].

Methods

Study Design

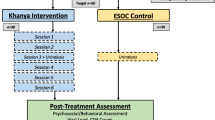

The study was a pilot randomized controlled trial of an intervention targeting PWH in Gugulethu Township, South Africa. We assessed acceptability and feasibility, along with fidelity to the intervention by peer interventionists, called “Treatment Ambassadors.” Eighty-four participants completed structured surveys at baseline; follow-up assessments occurred at three and 6-months post-baseline. Participants were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to intervention (n = 41) or control (n = 43) arms at baseline. We also conducted an evaluation of the different intervention components and their implementation using semi-structured exit interviews with 30 randomly selected participants (25 from the intervention arm and 5 from the control arm) upon completion of the intervention [34]. All study visits (for intervention and assessment sessions) took place in a neutral non-clinical space (e.g., a church or community center) that was convenient for participants.

Description of the Treatment Ambassador Program

The Treatment Ambassador Program was iteratively developed in partnership with a Community Advisory Board, a group of key stakeholders in the Gugulethu community, who provided crucial contextual expertise and guidance in the development of the intervention. Specifically, the research team met with the Community Advisory Board three to four times per year, beginning in the pre-pilot phase, and through the end of the study to solicit feedback, and provide progress reports. Core intervention components included one-on-one client-centered counseling sessions and patient navigation. The intervention development was based on prior research [7, 35, 36] and findings from a large systematic review focused on understanding why PWH delayed or discontinued treatment in low- and middle-income countries [6]. Building on the Theory of Triadic Influence (TTI) [37], this intervention was designed to address individual-, social-, and structural-level barriers to ART initiation (see Fig. 1). TAP was hypothesized to work through several mechanisms and levels as framed by the TTI: (1) individual-level factors, including attitudes and beliefs about treatment, by building the knowledge base and trust of treatment for participants, while promoting self-efficacy and effective coping strategies; (2) social-level factors through social interactive processes that address HIV-related stigma and the need for disclosure; and (3) structural-level factors through facilitating engagement with clinic providers.

The intervention was tailored for the South African context using content and strategies from Motivational Interviewing (MI)-enhanced interventions that were developed and tested in the U.S [38,39,40]. As shown in Table 1, the full intervention consisted of eight sessions over 8–14 weeks for PWH who had not initiated treatment within 6 months of testing or had previously initiated ART, but been off treatment for over 6 months. MI strategies were used to create collaborative, goal-oriented communication focused on enhancing intrinsic motivation for behavior change by helping individuals to identify discrepancies between their stated goals and values, and current behavior [41]. Treatment Ambassadors helped clients to develop problem-solving skills to overcome key individual- and social-level barriers. Interventions using MI have demonstrated acceptability, feasibility, and fidelity in research in South Africa [42, 43].

Two Treatment Ambassadors were identified by study staff from a group of PWH previously selected from among the 2500 PWH in care at Gugulethu Community Health Centers to be trained as clinic counselors [44]. The Treatment Ambassadors underwent two rounds of three full days of intensive training over 6 months in MI techniques and TAP intervention content and structure. Consistent with the client-centered counseling approach, TAP counselors tailored session content to individual participants’ needs, focusing on improving treatment knowledge, promoting self-efficacy and coping skills, and supporting perceptions of treatment benefits. Treatment Ambassadors conveyed stories about their own experiences with these issues to participants, in order to act as role models for ART initiation. Each session involved goal setting and review of the participant’s personal treatment plan. Treatment Ambassadors offered to accompany participants to their preferred treatment center and served as a liaison with healthcare providers. They also provided information about how to link to services and encouragement to link to other services (e.g., substance use/mental health), as well as practical tips for navigating through clinic, including reviewing a detailed map of the steps required to initiate care in a standard public facility.

Participants

Participants (n = 84) were recruited between January and December 2017 in Gugulethu using a community-based hybrid approach comprised of targeted sampling in community-based organization and peer-to-peer recruitment through snowball sampling in Gugulethu township, and distributing fliers in the community describing the study with contact information provided. The study protocol and data collection instruments were approved by Human Subjects Committees at Partners Healthcare and the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent. Study data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based, Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool [45]. The study was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03099707). This study was designed as a feasibility and acceptability trial, rather than an effectiveness trial. As such, the sample size was not determined by power analysis to detect an effect size. Rather, the sample size was the largest that was feasible in the context of a small study of a novel intervention.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria included people who: (1) were living with HIV; (2) were of 18 years of age or older; (3) had not initiated ART within 6 months of learning their status or were off treatment for at least 6 months; (4) lived within 60 km of the testing center; and (5) were English- or isiXhosa-speaking. All people living with HIV were eligible for treatment under current South African guidelines, including peer-based treatment preparedness sessions [46]. Participants were excluded if they were unable to provide informed consent, if they had been on ART within the last 6 months, or if they were women who reported current pregnancy at the time of consent (since they qualified for intensive adherence support under current South African guidelines). ART laboratory data were obtained from the South African National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) database [47,48,49]. Researchers screened 133 potential participants. Of these, 26 did not meet enrollment criteria due to an inability to sign informed consent (one individual) or recent ART use within the last 3 months (25 individuals). An additional 23 were withdrawn by the Principal Investigator due to not meeting inclusion criteria, with three individuals ultimately found to be HIV-negative, and 20 others appeared to be actively or recently on treatment based on data from NHLS (Fig. 2). Ultimately, 84 participants were successfully enrolled.

Randomization

Participants were randomized by the study’s principal statistician in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention or control arm after the baseline assessment was completed. Those in the control arm received no intervention, beyond engagement with study staff for the assessments at designated times. All participants had access to free comprehensive HIV care and services in community-based settings. Field staff worked with the principal statistician to develop a randomization assignment, and assignments were stored in a password-protected file only available to the principal statistician. Staff and participants were not blind to intervention arm assignment, however, researchers were blinded during consent and the baseline survey, prior to randomization, so that the baseline measures were not biased by foreknowledge of conditions. In addition, team members assessing clinical outcomes in NHLS were blinded to the study arms of the participants during data collection. Of the 84 participants enrolled, 43 were allocated to the control arm and 41 to the intervention arm (Treatment Ambassador Program).

Assessment Procedures

Overview

Eligible individuals provided signed informed consent for study participation and accessing NHLS data. They participated in structured, 60-min baseline and follow-up surveys conducted in person with a bilingual (English and isiXhosa) research assistant. Baseline and follow-up surveys used the same measures; follow-up assessments were conducted at Time 2 (T2; 3 months post-intervention, focused mainly on the past 3 months) and Time 3 (T3; 6 months post-intervention, focused mainly on the past 6 months). Participants received Rand 100 (roughly $8 U.S.) for each baseline and follow-up assessment for their time and fare for local public transportation, and a bonus of Rand 200 (roughly an additional $16 U.S.) for completing all three surveys. Participants in the intervention arm received Rand 20 (roughly $1.50 U.S.) for each session to cover transportation to and from the venue.

NHLS Data

We assessed ART initiation within 3 months after study enrollment. While the follow-up assessments were conducted at three and 6 months post-intervention, treatment initiation was measured only at 3 months to capture the importance of early treatment initiation, which is associated with better long-term outcomes [50, 51]. ART initiation was assessed using NHLS data, based on a measure of creatinine that was performed prior to initiation of tenofovir (part of the standard first-line ART regimen in South Africa). ART workup blood tests as recorded in NHLS have been previously validated as an accurate measure to impute dates of treatment initiation among South African PWH who are receiving public-sector HIV care [52]. All treatment initiation was verified with prescription data and pill bottle visualization, in which participants brought their medications to a visit with the Treatment Ambassador, to show them they had initiated treatment.

Survey Instrument

Survey measures were administered at baseline and follow-up to assess psychosocial characteristics, as well as sociodemographic and medical characteristics potentially related to behavior at baseline and at follow-up in both arms of the study to evaluate the moderators and mediators of intervention effects (see Table 2). The TTI states that health related behaviors are shaped by individual-, social-, and structural-level factors and thus, the survey attempted to analyze barriers at these three levels. Individual-level factors included self-perceived health and wellness, as well as coping and mental health. These factors were measured using the Short Form-8 questionnaire to capture general health perceptions, the AUDIT scale to measure alcohol and recreational drug use, the Brief COPE to assess how participants deal with stressors, and the Patient Health Questionnaire to measure depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints [53,54,55,56,57,58]. The social-level factors included were perceived social support, measured using the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, HIV-associated stigma (internalized, enacted, and anticipated), measured using the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale and the HIV stigma framework, and disclosure concerns, measured using HIV stigma scale [59,60,61,62]. Structural-factors included barriers to accessing ART and trust in ART efficacy, measured by assessing competing needs and barriers to care in the past 6 months and a scale based on the RAND HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study, respectively [63,64,65].

Intervention and Assessment Feasibility: Study Participant Tracking Records and Fidelity Ratings

Assessment of intervention feasibility measures included participation withdrawal and retention rates for the intervention and study assessments. We used the following benchmarks to assess feasibility of the intervention: ≤ 10% withdrawing from the intervention arm, ≥ 50% enrollment of eligible participants, ≥ 80% completion of 3-month and 6-month outcome assessments [66]. Sessions were recorded and scored to assess Treatment Ambassador’s fidelity to the intervention content and MI style using established procedures [40, 67, 68]. Trained independent isiXhosa raters coded the extent to which Treatment Ambassadors addressed key session content as presented in the manual and training. Fidelity to key content delivery was measured using a checklist, rated as “yes” (1), “no” (0), “partially” (0.5), or “N/A” (excluded). Scores for each content item were summed to create a total score for each session. The overall average content fidelity for all sessions was then calculated by averaging all the individual total session scores, with a 1 indicating perfect fidelity to the manualized session content. Fidelity to the MI strategies presented in the manual and training (i.e., reflective listening, asking permission, open ended question, expressing empathy, summaries, and overall quality) was assessed using a modified version of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Code [22] which is scored on a 7 point scale. An overall average of 5 and above indicates excellent adherence to MI style throughout sessions.

Intervention Acceptability: Qualitative Data

Semi-structured exit interviews were performed after completion of the intervention with a random subset of 30 participants (25 intervention, 5 control; 100% Black African; 96% females). While the focus of these semi-structured interviews was to understand the acceptability of the intervention, we also chose to interview a small number of control participants to provide a comparison to intervention participants to understand perceived barriers to and facilitators of ART initiation in the absence of the intervention [29]. Interviews were conducted in isiXhosa or English, at participant’s preference and audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated as required. Qualitative data were entered into NVivo 10© (QSR International Pty Ltd 2014) software.

Data Analysis

Data analysis focused on characterizing perceived acceptability (extent to which people receiving an intervention consider it to be appropriate), which was operationalized in terms of attitudes toward and perceptions of the intervention and its components [23]. Sample questions to assess perceived acceptability included questions regarding the structure of the sessions, comfort with the Treatment Ambassador, cultural sensitivity, and the content and length of the survey. Using an inductive approach based upon grounded theory, categories were constructed to name, define, and illustrate content themes [69]. We searched interview data for key concepts that pertained to intervention acceptability and displayed the text in matrices to identify patterns. Patterns of content appearing repeatedly in the data formed the basis for thematic categories. Coding began with a provisional start-list of themes based on prior research. Twenty percent of the interviews (n = 6) were independently read and new themes were iteratively generated based on identifying themes that were not present in the start-list, which resulted in a codebook. The team members coded 20% additional interviews (n = 6) to calibrate the methods of evaluation, and one individual, using the standards established, coded the remaining interviews (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.82). For each of the seven survey measures, we compared responses at 6 months by computing the mean response for each arm, a 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the between-arm difference in means, and a permutation test p-value for the between-arm difference in means adjusted for each participant’s baseline score. To assess preliminary efficacy, rates of ART initiation at 3 months for the two arms were compared by computing the relative “risk” of initiation and testing for an association between arm and initiation rate using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Participants

At enrollment (Table 3), participants’ median age was 34 (IQR 29, 43) years. Over three-quarters of the participants were female, and the majority were unemployed (88% in the control arm and 98% in the intervention arm). The median time since taking a diagnostic HIV-test was 33 (IQR 21, 53) months. Over half of the participants reported testing last for HIV due to “feeling sick” (51% in the control arm and 54% in the intervention arm). Across both arms, participants’ self-perception of health was good, very good, or excellent in the month prior to the intervention (86% in the control arm and 90% in the intervention arm); however, participants indicated challenges with coping (median 1 on a scale of 1 to 4), and over 90% reported food insecurity. There were no statistically significant differences at baseline between those assigned to the intervention and control arms on psychosocial, sociodemographic, and medical characteristics.

Feasibility and Fidelity

The intervention was highly feasible, with 90% of the 41 participants randomized to the intervention arm participating in the full intervention (three voluntarily withdrew before the intervention started and one voluntarily withdrew prior to completing the intervention). All 38 participants who started the intervention completed both the 3 and 6-month follow-up surveys. There were no adverse or unintended effects reported during the intervention or follow-up assessments.

The intervention counselors maintained high levels of fidelity. All eight sessions delivered to the 38 intervention participants who completed the full intervention were recorded, totaling in 256 recorded MI sessions. Roughly 25% were chosen at random to assess session content and MI style fidelity. Of 73 sessions (29%) randomly selected to assess content fidelity, the median score was 0.90 (IQR 0.81–0.95), with a score of 1 indicating that all content described in the manual was delivered in the session. Of 71 sessions (28%) randomly selected to assess MI style, the median intervention session score was 4.3 (IQR 3.6–5.0) indicating strong use of MI strategies during counseling sessions.

Intervention Acceptability—Qualitative Data

The exit interview data indicated that all 25 intervention participants interviewed found the intervention to be highly acceptable. Acceptability clustered around five primary themes: (1) support from an “ideal” partner promoting self-reflection; (2) support of autonomy and intrinsic motivation while promoting disclosure; (3) assistance with navigating a challenging clinical environment; and (4) the need to unpack barriers, including myths and misinformation, anticipated and internalized stigma, and denial. Table 4 summarizes results from our qualitative interviews. Individuals who engaged in the intervention but did not start ART reported several barriers to ART initiation that were not addressed by the intervention, including: structural challenges getting to clinic and waiting to be seen; competing needs and priorities; and social isolation Suggestions to improve the intervention from participants included: direct delivery of ART by nurses outside of a clinic setting; strategies to improve self-efficacy; and ongoing education regarding safety of ART usage (especially if using alcohol). See Table 5.

Survey Results

There was little evidence of difference between arms at 6 months on the survey measures, including ARV efficacy, social support, internal stigma, disclosure concern, and barriers (see Table 6). The exception was the depression measure (PHQ9). On average, intervention participants reported better (lower) scores (mean 0.32, SD 0.24) than control participants (mean 0.61, SD 0.56) (95% CI for difference in means = − 0.48, − 0.09; permutation test p-value, controlling for baseline scores = 0.002).

Preliminary Efficacy

Rates of confirmed ART initiation by 3 months in the intervention and control arms were 12% (5/41) and 2% (1/43), respectively (Fisher exact p-value = 0.105; Cohen’s h = 0.41). Relative “risk” of ART initiation was 5.2 (95% CI 0.6–43.0). Rates of confirmed ART initiation by 3 months among those who were previously on ART in the intervention and control arms were 33% (5/15) and 14% (1/7), respectively (Fisher exact p-value = 0.616; Cohen’s h = 0.45, indicating a meaningful effect size). Relative “risk” of ART initiation for this subgroup was 2.3 (95% CI 0.3–16.4). This exploratory study was not powered for definitive null hypothesis significance testing, but the first test of this new intervention was designed to explore preliminary efficacy.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we report on a novel behavioral intervention targeting a population at high-risk for poor health outcomes: PWH from a hard-to-reach population in South Africa who were aware of their status but were not taking ART nor engaged in care. These participants, all recruited though peers and other community members, were diagnosed with HIV on average 3 to 4 years prior to enrolling in the study. The Treatment Ambassador Program was shown to be highly acceptable and feasible as a tool to improve initiation among a highly disenfranchised population. In addition, participants in the intervention arm reported improvements in symptoms of depression as compared to the control arm. Peers, whom we identified as Treatment Ambassadors, delivered the intervention with a high degree of fidelity, despite having no formal advanced degree or counseling training. Our promising findings demonstrate the potential for peer-delivered interventions and provide support for an approach that is both acceptable and feasible.

The use of peers as counselors is based on a substantial literature that supports linking participants with peer supporters to promote HIV-related behavior change, with effect sizes generally comparable to provider-led interventions [24,25,26, 35, 70, 71]. Participants enrolled in the Treatment Ambassador Program cited gaining medical knowledge, social support, self-efficacy, support with disclosure, and overcoming challenges with stigmatizing health systems as critical aspects of the program. Among those initiating ART, intrinsic motivation, disclosing to a trusted friend or family-member, and an ability to overcome barriers appeared to be essential mechanisms of action. These findings are consistent with literature demonstrating that peer supporters can be credible role models and challenge negative peer norms about care and ART [27, 72,73,74,75]. Moreover, support with clinical navigation has been shown to improve engagement and retention of low-income PWH in HIV care [76], including in sub-Saharan Africa [13, 28, 77]. This component was based on the Health Resources and Service Administration HIV System Navigation model [78], and informed by prior research in South Africa [79], focusing on a strengths-based approach [80]. The individuals initiating ART in our sample described that the level of support provided by the Treatment Ambassadors was largely missing from their daily lives, supporting prior research that showed that PWH struggle to trust family and friends due to concerns about stigma and discrimination [81].

Given that South Africa has the highest burden of HIV/AIDS but a shortage of trained health care workers, task-shifting and sharing of health service responsibilities are essential for a treatment model to be sustainable and scalable in this setting [27, 74, 75, 82]. Peer-delivered, community-based interventions, such as the Treatment Ambassador Program, present both a scalable and sustainable solution to improving treatment for high-risk populations of PWH who struggle to engage in care. The feasibility and acceptability of this intervention suggest that there is untapped value in leveraging community resources to better engage these key populations. Peer interventions have potential for high-impact in low resource settings, as they reduce the burden on health care workers and strained health systems. Despite concerns that peer supporters could fail to deliver interventions with a high degree of fidelity, the Treatment Ambassadors in this study demonstrated that peers can be trusted to deliver interventions and should be leveraged in settings with shortages of health care workers. While past studies have primarily evaluated the impact of interventions focused on improving ART adherence [39, 79] and engagement in HIV primary care [83, 84], or promoting early ART initiation within the context of “treatment for all,” [85] few behavioral interventions have been designed for PWH who have delayed, declined, or discontinued ART [51].

This intervention showed high levels of feasibility and acceptability amongst a population that had remained out of treatment for, on average, 33 months since initial testing. This demonstrates the promise of differentiated service delivery models in engaging populations who have delayed or declined ART for an extended period, especially highly disenfranchised populations such as the one identified in this study. This is consistent with previous research that has found that peer supporters have a unique ability to access hidden populations that may have limited interactions with the health care system [86]. Individuals in this population described persistent barriers to accessing care, such as structural challenges in getting to the clinic, competing needs and priorities, and social isolation. In the study population, individuals experienced high levels of food insecurity and reported that needing money for food was the most common reason to delay or decline health care. Given that food insecurity is commonly cited as a reason for poor clinic attendance and poor ART uptake and adherence, it is important to address this competing need in order to improve adherence in this population [87]. While this intervention shows considerable promise and potential in reaching these individuals, modifications to the intervention are needed for the next phase of this research program to address persistent barriers, and future studies with a longer follow-up period and a study of intervention mediators may shed light on whether the impact can be augmented.

Several key limitations in our study should be considered. First, this is an exploratory study with a modest sample size. Data on effects of psychosocial factors in the pilot study were generally inconclusive. For example, while participants who initiated ART reported disclosure to others as a critical step to initiation, this sample was small and thus, these results do not necessarily imply that disclosure is a necessary step in ART initiation. Studies with a larger population and a longer follow-up may provide more detail on specific mechanisms of action in this population. In addition, participants in our study were diagnosed with HIV for, on average, 3 years before enrolling. Prior data collected at this site show that the longer PWH wait from the point of testing to initiate ART, the less likely they are to ever engage in care [83]. These data are supported by other studies in sub-Saharan Africa [84, 85]. Therefore, the Treatment Ambassador Program has the potential to be more efficacious if offered closer to the time of HIV testing. Further, participants highlighted persistent challenges with initiating treatment, such as structural challenges in getting to the clinic, competing needs and priorities, and social isolation, despite the acceptability and feasibility of this intervention. Future research is necessary that builds upon this intervention by incorporating the solutions to these barriers suggested by participants, such as direct delivery of ART, enhanced channels of social support, and ongoing education about the safety of ART usage.

Conclusions

There is an urgent need for interventions to improve rates of ART initiation among the 40% of South Africans living with HIV who are not on treatment. The present intervention was found to be highly acceptable and feasible, providing a potential strategy to engage a highly disenfranchised population who are not traditionally represented in standard healthcare settings. The model presented here shows a promising pathway to harness the power of peers in delivering interventions, while maintaining a high degree of fidelity. Beyond this, it identifies several promising intervention components that merit further study.

References

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Country Report—South Africa. 2018. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Ending AIDS: progress towards the 90–90–90 targets. United Nations. 2017. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/Global_AIDS_update_2017_en.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Cloete C, Regan S, Giddy J, et al. The linkage outcomes of a large-scale, rapid transfer of HIV-infected patients from hospital-based to community-based clinics in South Africa. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1(2):ofu058.

Fox MP, Shearer K, Maskew M, Meyer-Rath G, Clouse K, Sanne I. Attrition through multiple stages of pre-treatment and ART HIV care in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e110252.

Plazy M, Dray-Spira R, Orne-Gliemann J, Dabis F, Newell ML. Continuum in HIV care from entry to ART initiation in rural KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(6):680–9.

Plazy M, Orne-Gliemann J, Dabis F, Dray-Spira R. Retention in care prior to antiretroviral treatment eligibility in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e006927.

Bor J, Chiu C, Ahmed S, et al. Failure to initiate HIV treatment in patients with high CD4 counts: evidence from demographic surveillance in rural South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2018;23(2):206–20.

Katz IT. Linkage and retention to care for vulnerable populations in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Paper presented at: international conference on HIV treatment and prevention adherence, Miami, FL, USA; 2018.

Katz IT, Bogart LM, Dietrich JJ, et al. Understanding the role of resilience resources, antiretroviral therapy initiation, and HIV-1 RNA suppression among people living with HIV in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. AIDS. 2019;33:S71–9.

Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care: a systematic review. AIDS. 2012;26(16):2059–67.

Katz IT, Dietrich J, Tshabalala G, et al. Understanding treatment refusal among adults presenting for HIV-testing in Soweto, South Africa: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(4):704–14.

Genberg BL, Shangani S, Sabatino K, et al. Improving engagement in the HIV care cascade: a systematic review of interventions involving people living with HIV/AIDS as peers. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(10):2452–63.

Steward WT, Sumitani J, Moran ME, et al. Engaging HIV-positive clients in care: acceptability and mechanisms of action of a peer navigation program in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2018;30(3):330–7.

Duncombe C, Rosenblum S, Hellmann N, et al. Reframing HIV care: putting people at the centre of antiretroviral delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(4):430–47.

International Aids Society (IAS). Differentiated Care for HIV: A Decision Framework for Antiretroviral Therapy. IAS. 2016. https://www.differentiatedcare.org/Portals/0/adam/Content/yS6M-GKB5EWs_uTBHk1C1Q/File/Decision%20Framework%20REPRINT%20web.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Rutter M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24(2):335–44.

Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. Br J Soc Work. 2008;38(2):218–35.

Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225–36.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57.

Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(3):488–531.

Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(6):1038–46.

Moyers TMT, Manuel J, Miller WR. The motivational interviewing treatment integrity (MITI) code, version 2.0. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico CoA, Substance Abuse and Addictions (CASAA); 2003.

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):88.

Cully JA, Mignogna J, Stanley MA, et al. Development and pilot testing of a standardized training program for a patient-mentoring intervention to increase adherence to outpatient HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(3):165–72.

Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin K, Yang C, Sun CJ, Latkin CA. Results of a randomized controlled trial of a peer mentor HIV/STI prevention intervention for women over an 18 month follow-up. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1654–63.

Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, et al. Demonstration and evaluation of a peer-delivered, individually-tailored, HIV prevention intervention for HIV-infected MSM in their primary care setting. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(5):949–58.

Selke HM, Kimaiyo S, Sidle JE, et al. Task-shifting of antiretroviral delivery from health care workers to persons living with HIV/AIDS: clinical outcomes of a community-based program in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(4):483–90.

Hatcher AM, Turan JM, Leslie HH, et al. Predictors of linkage to care following community-based HIV counseling and testing in rural Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1295–307.

Katz I, Bogart LM, Courtney I, et al. South Africans living with HIV who delay or discontinue treatment: a qualitative study to understand the mechanisms of action of the treatment Ambassador Program (TAP). In: Paper presented at: international conference on HIV treatment and prevention adherence, June 8–10, 2018. Miami Beach, FL.

Katz IT, Bogart LM, Courtney I, et al. The Treatment Ambassador Program: a pilot randomized controlled trial for people living with HIV in South Africa who delay or discontinue treatment. In: Paper presented at: international conference on HIV treatment and prevention adherence, June 8–10, 2018. Miami Beach, FL.

Katz IT, Ehrenkranz P, El-Sadr W. The global HIV epidemic: what will it take to get to the finish line? JAMA. 2018;319(11):1094–5.

Hontelez JA, Newell ML, Bland RM, Munnelly K, Lessells RJ, Barnighausen T. Human resources needs for universal access to antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a time and motion study. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10:39.

Van Damme W, Kober K, Kegels G. Scaling-up antiretroviral treatment in Southern African countries with human resource shortage: how will health systems adapt? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(10):2108–21.

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann ML, Hanson WE. Advanced mixed methods research designs. 2003.

Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Courtney I, et al. Exploring treatment needs and expectations for people living with HIV in South Africa: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2543–52.

Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Laurenceau JP, et al. Internalized HIV stigma, ART initiation and HIV-1 RNA suppression in South Africa: exploring avoidant coping as a longitudinal mediator. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(10):e25198.

Flay B, Snyder F, Petraitis J. The theory of triadic influence. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2019.

Bogart LM, Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of rise, a community-based culturally congruent adherence intervention for black americans living with HIV. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(6):868–78.

Wagner GJ, Bogart LM, Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Mutepfa KD, Risley B. Increasing antiretroviral adherence for HIV-positive African Americans (Project Rise): a treatment education intervention protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(1):e45.

Goggin K, Gerkovich MM, Williams KB, et al. A randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of motivational counseling with observed therapy for antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):1992–2001.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Publications; 1991.

Cornman DH, Christie S, Shepherd LM, et al. Counsellor-delivered HIV risk reduction intervention addresses safer sex barriers of people living with HIV in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Psychol Health. 2011;26(12):1623–41.

Bogart LM, Skinner D, Thurston IB, et al. Let’s Talk!, a South African worksite-based HIV prevention parenting program. J Adolesce Health. 2013;53(5):602–8.

Grimsrud A, Lesosky M, Kalombo C, Bekker L-G, Myer L. Implementation and operational research: community-based adherence clubs for the management of stable antiretroviral therapy patients in Cape Town, South Africa A Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(1):e16–23.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Western Cape Government. The western cape consolidated guidelines for HIV treatment: prevention of mother- to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), children, adolescents and adults. In: Provincial government of the western cape-department of health. Cape Town, South Africa: Western Cape Government Health; 2018.

Bor J, MacLeod W, Oleinik K, et al. Building a national HIV cohort from routine laboratory data: probabilistic record-linkage with graphs. bioRxiv. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1101/450304.

Carmona S, Bor J, Nattey C, et al. Persistent high burden of advanced HIV disease among patients seeking care in South Africa’s national HIV program: data from a nationwide laboratory cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(suppl_2):S111–7.

National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS). National health laboratory service 2017/18 annual report. Johannesburg: NHLS; 2018.

Bassett IV, Wang B, Chetty S, et al. Loss to care and death before antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa. JAIDS-J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(2):135–9.

Gwadz M, Applegate E, de Guzman R, et al. Why do people living with HIV/AIDS delay, decline, or discontinue antiretroviral therapy?: A mixed-methods exploration. American Public Health Association Conference, New Orleans, Louisiana; 2014.

Maskew M, Bor J, Hendrickson C, et al. Imputing HIV treatment start dates from routine laboratory data in South Africa: a validation study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):41.

Onagbiye SO, Moss SJ, Cameron M. Validity and reliability of the Setswana translation of the Short Form-8 health-related quality of life health survey in adults. Health SA Gesondheid (Online). 2018;23:1–6.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: a manual for users of the SF-8 health survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc. 2001;15(10):5.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Heever HVD. Prevalence of alcohol use and associated factors in urban hospital outpatients in South Africa. Int J Enviro Res Public Health. 2011;8(7):2629–39.

Louw GJ, Viviers A. An evaluation of a psychosocial stress and coping model in the police work context. SA J Ind Psychol. 2010;36:1–11.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):87–93.

Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–95.

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29.

Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, et al. Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(5):597–606.

Sileo KM, Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, et al. HIV fatalism and engagement in transactional sex among Ugandan fisherfolk living with HIV. SAHARA-J: J Soc Asp HIV/AIDS. 2019;16(1):1–9.

Wagner GJ, Kanouse DE, Koegel P, Sullivan G. Correlates of HIV antiretroviral adherence in persons with serious mental illness. AIDS Care. 2004;16(4):501–6.

Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–39.

Catley D, Harris KJ, Goggin K, et al. Motivational Interviewing for encouraging quit attempts among unmotivated smokers: study protocol of a randomized, controlled, efficacy trial. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):456.

Catley D, Goggin K, Harris KJ, et al. A randomized trial of motivational interviewing: cessation induction among smokers with low desire to quit. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(5):573–83.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California; 2008: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/basics-of-qualitative-research. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

Mills EJ, Lester R, Thorlund K, et al. Interventions to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Africa: a network meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2014;1(3):e104–11.

Govindasamy D, Meghij J, Kebede Negussi E, Clare Baggaley R, Ford N, Kranzer K. Interventions to improve or facilitate linkage to or retention in pre-ART (HIV) care and initiation of ART in low- and middle-income settings–a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19032.

Wouters E, Van Damme W, van Rensburg D, Masquillier C, Meulemans H. Impact of community-based support services on antiretroviral treatment programme delivery and outcomes in resource-limited countries: a synthetic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:194.

Wools-Kaloustian KK, Sidle JE, Selke HM, et al. A model for extending antiretroviral care beyond the rural health centre. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:22.

Decroo T, Van Damme W, Kegels G, Remartinez D, Rasschaert F. Are expert patients an untapped resource for ART provision in Sub-Saharan Africa? AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:749718.

Duvivier H, Decroo T, Nelson A, et al. Knowledge transmission, peer support, behaviour change and satisfaction in post Natal clubs in Khayelitsha, South Africa: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):107.

Farrisi D, Dietz N. Patient navigation is a client-centered approach that helps to engage people in HIV care. HIV Clin. 2013;25(1):1–3.

Bassett IV, Coleman SM, Giddy J, et al. Sizanani: a randomized trial of health system navigators to improve linkage to HIV and TB care in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(2):154–60.

Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV system navigation: an emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S49-58.

Bassett IV, Giddy J, Chaisson CE, et al. A randomized trial to optimize HIV/TB care in South Africa: design of the Sizanani trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):390.

Saleebey D. The strengths perspective in social work practice. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2009.

Kaunda-Khangamwa BN, Kapwata P, Malisita K, et al. Adolescents living with HIV, complex needs and resilience in Blantyre, Malawi. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):35.

Ford N, Geng E, Ellman T, et al. Emerging priorities for HIV service delivery. PLOS Med. 2020;17(2):e1003028.

Katz IT. Bending the Arc on the HIV Epidemic: socio-behavioral interventions for people living with HIV in South Africa. In: Paper presented at: infectious diseases grand rounds, Boston Medical Center; 2018.

McNairy ML, Lamb MR, Abrams EJ, et al. Use of a comprehensive HIV care cascade for evaluating HIV program performance: findings from 4 Sub-Saharan African Countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(2):e44–51.

Hoffmann CJ, Mabuto T, Ginindza S, et al. Strategies to accelerate HIV care and antiretroviral therapy initiation after HIV diagnosis: a randomized trial. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(5):540–7.

Simoni JM, Nelson KM, Franks JC, Yard SS, Lehavot K. Are peer interventions for HIV efficacious? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1589–95.

The Lancet HIV. The syndemic threat of food insecurity and HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(2):e75.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the individuals who participated in this study, and the broader study team. The Treatment Ambassador Program (TAP) was supported by: National Institute of Health (NIH); Institute: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); Type: Planning Grant (R34). Project #: 5R34MH108393-02. Dr. Bogart was additionally support by P30MH058107. Dr. Bassett was supported to this work by a K24AI141036 grant from the NIH. The study can be referenced on Clinicaltrials.gov under the unique identifier NCT03099707. We particularly wish to acknowledge our Program Officer at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Michael Stirratt, Ph.D., Program Chief at the NIMH Division of AIDS Research for scientific guidance throughout the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Katz, I.T., Bogart, L.M., Fitzmaurice, G.M. et al. The Treatment Ambassador Program: A Highly Acceptable and Feasible Community-Based Peer Intervention for South Africans Living with HIV Who Delay or Discontinue Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Behav 25, 1129–1143 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03063-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03063-1