Abstract

This systematic review provides an examination of the status of HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for Black, heterosexual women in the U.S. from 2012 to 2019. Using PRISMA guidelines, 28 interventions were identified. Over half of the interventions were: conducted in the southern region of the U.S.; evaluated using a randomized controlled trial; focused on adults; used a group-based intervention delivery; were behaviorally focused and theoretically driven. None included biomedical strategies of PrEP, nPEP, and TasP. Few interventions included adolescent or aging Black women; none included their sex/romantic partners. Future studies dedicated to addressing the specific needs of subpopulations of Black, heterosexual women may provide opportunities to expand and/or tailor current and future HIV/AIDS prevention interventions, including offering participants with options to choose which, and the level of involvement, of their sex/romantic partner(s) in their sexual health decision-making. While strides to improve HIV prevention efforts with Black, heterosexual women have occurred, more is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2018, more than 7000 women were diagnosed with HIV in the United States [1]. Of these diagnoses, 85% (n = 6014) were attributed to heterosexual contact; more than 1000 cases were due to injection drug use [1]. Women’s risk for HIV can increase due to their partner(s) high-risk behaviors, such as unprotected sex with other partners (male or female) and/or injection drug use [2]. There is also a differentiation in HIV risk due to age. The 2017 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV Surveillance Report [3] noted women over the age of 25 had higher percentages of new HIV diagnoses (25–34: 27%; 35–44: 23%; 45–54: 20%) compared to adolescent women (13–24: 14%) and women over the age of 55 (> 55: 16%). However, not all women are equally affected by HIV.

Since 2014, Black women have accounted for the largest numbers of HIV diagnoses among females [1]. Black women currently account for 13% of the U.S. female population, yet in 2018, represented 58% of HIV diagnoses with 92% of these being attributed to heterosexual contact [1]. Unlike other female racial groups, Black women are at greater risk for HIV acquisition due to social and structural factors related to their: selection of sexual partners [4]; their own and partners’ incarceration [5,6,7]; uninformed HIV status or partner’s HIV status [8,9,10]; poverty [11, 12]; low education [11, 13]; and lack of access to healthcare [12]. Insufficient knowledge of HIV prevention methods, racism, unemployment, intimate partner violence (IPV), and gender roles also affect Black women’s risk for HIV [14, 15]. The added responsibilities of caring for children and other family members can further influence Black women’s ability to cope and adjust to an HIV diagnosis [16].

With regard to women living with HIV (WLWH), this group represented 24% (n = 245,154) of those diagnosed with HIV in the U.S.[1]. Compared to HIV-negative women, WLWH experience different social and structural barriers relative to access to medical care and treatment [17, 18]. Adherence to HIV care is the most important factor that can improve health outcomes for individuals living with HIV. In the U.S., obtaining regular HIV care and viral suppression has been identified as an issue among Black individuals [19]. Social inequalities, domestic violence, and cultural expectations can further marginalize WLWH [17]. Compared to men living with HIV, WLWH are disproportionately affected by trauma experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder [20, 21]. WLWH are at risk for mental health disorders due to HIV related stigma [22,23,24] and perceived discrimination [23]. Lack of knowledge concerning risk of HIV transmission, lack of HIV status disclosure, and delays in linkage to care further affect WLWH. Additionally, WLWH with abusive histories have been identified as having higher rates of unprotected sex, high numbers of sexual partners, and poor adherence to treatment [25,26,27].

Regional disparities in HIV diagnosis also exist for Black women. The Southern region of the U.S. (herein referred to as the ‘South’) is the epicenter of the HIV epidemic and includes the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. In 2018, the South had the highest rate of HIV diagnosis (15.6 per 100,000) and contributed to more HIV diagnoses among females than any other region (n = 3988) [1]. Black women in the South also had the highest rate of HIV diagnoses compared to all other female racial groups (24.6 per 100,000) [1], and accounted for 69% of all diagnoses among women in that region [2, 28, 29]. High rates of HIV diagnoses in the South may be due to poor population health, high poverty rates, and negative health outcomes for HIV-infected individuals [28,29,30]. Despite these statistics and known factors related to Black women’s risk for HIV acquisition and/or onward transmission, limited research has been done to understand the current status of HIV and AIDS prevention interventions for Black women in the U.S.

Systematic Reviews Examining HIV Prevention Interventions for Black Women

Prior systematic literature reviews have examined HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for Black women in various contexts, including: sexual health [31]; addressing depression through sexual risk reduction [32]; HIV testing [33]; HIV risk reduction [34]; stigma reduction [35]; social and structural determinants of HIV treatment and patient care [18, 36]; and self-management of HIV and diabetes [37]. While these published systematic reviews have expanded our scope of the types of interventions that are available for Black women, there are aspects of these reviews that warrant further investigation of the literature.

First, previous systematic reviews that examine HIV prevention interventions for Black women include literature published prior to 2012 [31, 36]. While doing so does provide an extensive overview of the literature, it may: (1) include prevention interventions that may no longer be available; (2) may not consider the epidemiological shift in new HIV/AIDS diagnoses (e.g., the increase in new HIV/AIDS diagnoses among women over age 25 (3) and the elderly population [38]); and/or (3) exclude interventions that may include recently developed biomedical HIV prevention strategies. Biomedical strategies for HIV prevention aim to significantly decrease the acquisition or onward transmission of HIV [39, 40]. Biomedical strategies for HIV-negative individuals include non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis, nPEP [41], and pre-exposure prophylaxis, PrEP [42]. Though not a new biomedical strategy, treatment as prevention, TasP [43, 44] and antiretroviral treatment, ART [45, 46] are for people living with HIV (PLWH).

Second, some prior systematic reviews have examined HIV/AIDS prevention interventions conducted both in the U.S. and internationally [36]. While examining domestic and international interventions simultaneously is noteworthy, perceptions of Black women’s risk and associated risk factors may differ in international countries compared to the U.S. (e.g., historical and cultural contexts relative to gender and health, differences in health care access). As such, there is a need to examine peer reviewed literature on HIV/AIDS prevention interventions among Black women primarily in the U.S.

Purpose

Since 2012, a systematic review on all HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for Black women in the U.S., not specific to a particular outcome or sub-population, and organized with consideration for newer strategies for HIV prevention, has not been conducted. The current systematic review aims to provide an overview by: (1) identifying HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for Black women in the U.S.; (2) describing the characteristics of these HIV/AIDS prevention interventions; and (3) providing recommendations for the improvement of current and future interventions for this population.

Methods

Search Strategy

To thoroughly examine published literature regarding HIV prevention interventions for Black heterosexual women in the U.S., the following electronic databases were searched: PubMed; Web of Science; Psych Info; EBSCOhost: Health Source (consumer edition and nursing/academic edition), CINHAL, and Academic Search Complete. In consultation with an informational services and instruction librarian, studies were identified using a combination of the following MeSH terms: African American women AND (HIV OR human immunodeficiency virus) AND (prevent* OR intervention OR risk OR reduc* OR program OR trial* OR experiment OR efficac* OR impact) NOT transgender NOT incarcerated. To provide a more updated inquiry, two separate searches were conducted: May to August 2018 and November to December 2019. The same databases and search terms were used for each search. For both time frames, the query was modified to fit specific requirements of each of the databases. Manual review of reference listings from relevant studies was conducted to capture additional articles that did not appear in previous electronic database searches.

Criteria for Selecting Studies

Only literature published between January 2012 and December 2019 were included in the current review. The year 2012 was chosen as a cut-off date for two reasons. First, Truvada® (a composite of tenofovir and emtricitabine) was not approved by the FDA for PrEP until 2012. Second, other prevention strategies were not as prominent in the U.S. prior to 2012 (e.g., treatment as prevention, TasP [43, 44] and couples-based HIV testing and counseling, CHTC) [47,48,49].

Women within the prison system are disproportionately impacted by HIV [50,51,52]. The environment (e.g., the prison infrastructure [53, 54], prison management [53, 54], and allocation of housing) [55], as well as ethical considerations regarding HIV/AIDS clinical research among those in prison [56] can elevate women’s vulnerability to (and factors associated with) HIV [53,54,55, 57]. Due to these differences in environmental, social, and economic factors, the HIV prevention needs required for women within the prison system greatly differ from women not within the prison system. For these reasons, any HIV/AIDS prevention interventions that focused on women with criminal justice involvement, incarcerated women, or women recently released from prison were not included in the current review. Additionally, due to the unique HIV risk factors and characteristics of transgender women [58, 59] compared to cisgender heterosexual women, interventions that focused on transgender women were also excluded from this review.

Target Population

Black heterosexual women were the population of interest for the current review. Interventions were not excluded if they had populations of pregnant and/or adolescent Black women.

Interventions

Interventions specifically intended for Black women, or those that had samples of 50% or more Black women were included. Of these 9 interventions, an exception was made for one intervention (No. 22), which had a mixed sample of Black men and women with 45% of women identifying as Black. With respect to theoretical frameworks used for intervention development, for any intervention in which the theory was not easily identified, authors were contacted via email to obtain additional information regarding the theoretical framework(s) or approach(es) used for their respective interventions.

Comparison and Study Design

As the purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the interventions for Black women in the U.S., interventions were not excluded based on their study design.

Outcomes

All outcomes related to HIV/AIDS prevention were examined for each intervention. Specifically, interventions were categorized by the HIV status of their target population (HIV-negative, WLWH, or both HIV-negative and WLWH). The outcomes associated with each intervention by their sample’s HIV status was also reported.

Data Extraction

Titles and abstracts were screened by the first author, and all irrelevant articles were excluded. The second author screened the remaining titles and abstracts then excluded additional articles that did not meet the overarching goals of the current review. Full texts were obtained for the remaining articles and screened by the first author against a screening sheet detailing the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All articles that did not meet this criterion were excluded. Specifically, interventions that were not published between January 2012 and December 2019; focused on women with criminal justice involvement, women who are incarcerated, women recently released from prison, or transgender women; did not include at least 50% or more Black women in their sample population; or intervention outcomes were not related to HIV/AIDS prevention were excluded. Next, the second author screened any articles that were deemed questionable against the inclusion and exclusion checklist to determine their inclusion. Once complete, the remaining articles identified through our search were put into Excel spreadsheets. The following information items were extracted from each article.

The article title, associated authors, year, abstract; and intervention name, study design, study location, timeline for data collection, sample size, serostatus of target population (i.e., HIV-negative, HIV-positive, or both), intervention aim or purpose, hypotheses and/or research question(s) (if applicable), outcome measure(s), intervention type (behavioral, biomedical, structural, or a combination of these), intervention approach (e.g., individual, group-based), population category (e.g., IDU, couples, pregnant women, adolescents, etc.), intervention description, duration of intervention, theoretical basis for intervention development, result(s) from testing the intervention, strength(s), and limitation(s). The spreadsheets combined to create a database for all information included in this review.

Results

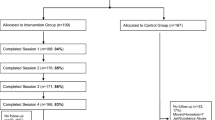

The findings from the current review were reported based on the PRISMA guidelines [60]. The following databases were searched for the current systematic review: PubMed (n = 387), EBSCOhost (Health Source, CINHAL, Academic Search Complete) (n = 392), Web of Science (n = 800), and Psych Info (n = 383), yielding a total of 1962 articles (see Fig. 1). Eight additional articles were identified through searching reference lists. After deleting all duplicates (n = 740), preliminary screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 1129 additional articles. These articles were excluded as they did not include heterosexual women, did not include 50% or more Black women, were international interventions, were conference abstracts, was an intervention that focused on populations other than heterosexual Black women or were irrelevant to the topic of the current review.

Full text articles of the remaining 101 records were examined by the first author and a second reviewer (blinded initials). After review, 61 additional published articles were excluded as they did not meet our inclusion criterion. Overall, 40 published articles, representing 28 interventions were included for review. A description of each intervention is located in Appendix A with the following characteristics: intervention name and supporting article(s) [by author(s) and publication year], study location, intervention type and design, sample (cases/controls), study purpose/aim, hypothesis and/or research question(s), approach of intervention delivery (e.g., web-based, group-based, individual, etc.), and description of the intervention. All interventions are referenced in the text using an intervention number (i.e., No. #). Three interventions did not specify an intervention name and will be referred to by the article’s author(s) and intervention number (No. 2, 10, 11).

Description of Interventions

Of the 28 interventions included in this review, 15 interventions were developed for HIV-negative Black women, 10 interventions for Black women living with HIV (BWLWH), and 3 interventions included both BWLWH and HIV-negative Black women. Eighteen interventions focused specifically on Black participants as the population of interest (i.e., 100% of the sample identified as Black), whereas nine interventions (Nos. 4, 6, 12, 15, 16, 19, 22, 25, 26) had at least 50% Black women within their sample (e.g., oversampled Black women) (see Appendix A). Of these 9 interventions, an exception was made for one intervention (No. 22), which had a mixed sample of Black men and women with 45% of women identifying as Black. All 28 interventions were behaviorally focused. Nineteen of the interventions were conducted in the South and/or evaluated using a randomized control trial (RCT). The other study designs that were used to test for intervention efficacy were: quasi-experimental (Nos. 2, 5, 10, 11, 13, 17, 20, 24); secondary data analysis (No. 17); single case study (No. 26); intent-to-treat (No. 5); mixed methods (No. 19); and a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods (not mixed methods) (No. 16).

Just over half of the interventions were delivered in either small or large groups (n = 16) (Nos. 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 13–15, 17, and 21–27), where 12 interventions used other approaches for delivery: individual [i.e., one-on-one (No. 16, 20, and 28)]; via an iPod touch (No. 19); a combination of group and individual components (Nos. 4, 9, 18); the web/Internet (Nos. 1, 6, 8); theater (No. 2); through the use of amenities on a college campus (i.e., condom dispensers) (No. 11).

Population

All interventions included heterosexually-identified, Black women. More than 80% of interventions included adult Black women (aged 18 years or older) (n = 23); however, 5 of the interventions included Black women who were between the ages of 13 and 20 years old and HIV-negative (Nos. 1, 7, 9, 14, and 15; refer to Appendix A for specific age ranges). Three interventions were developed for aging Black women (Nos. 22, 23, and 26), including one (No. 26) that was adapted from SISTA (No. 5). Three interventions were developed for both men and women (i.e., not couples) (Nos. 12, 16, and 21), and did not specifically address relationship-related issues. None of the interventions identified in the current review were created for, or included couples of Black women and their sexual or relationship partner(s).

At-risk Sub-groups

Among all interventions, only 6 focused on women identified as a ‘at risk’ sub-group for HIV (Nos. 5, 8, 9, 10, 21, 28) [2, 3, 28, 61]. For example, one intervention focused on sexually active substance abusing Black women (No. 9) whereas a different intervention was designed for women who had experienced IPV (No. 10) based on: (1) having experienced physical abuse, rape, or sexual abuse within 2 years prior to intervention participation, and (2) having had sex with an intimate partner when (the individual) did not want to within 2 years prior to intervention participation [62]. With respect to drug and/or alcohol use, one intervention was geared towards Black women who were non-injecting crack cocaine users (No. 21), and one focused on Black women who traded sex for money or drugs (No. 28). For individuals living with HIV, there are some groups who are more likely to transmit HIV to others and/or experience higher stigma, stress, and/or lower social support [63, 64]. The current review identified three interventions that enrolled women meeting some of this criterion (Nos. 20, 24, 25). Sister to Sister (No. 20) was adapted to meet the needs of homeless Black women living in Los Angeles County [65]. Another example is Project THANKS (No. 24), which aimed to prevent and manage the multiple conditions of HIV and other chronic diseases among BWLWH with comorbidities who are substance abusers. Of interest, only one intervention aimed to improve family functioning by reducing childbearing stressors among mothers living with HIV (MOMS, No. 25).

Culturally Informed Interventions

Eleven interventions were culturally informed, where direct input from members of the target population was obtained during intervention development, which may have included the adaptation of specific content or messaging to help ensure the intervention was culturally appropriate and to help increase engagement (Nos. 1, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 20, 23, 24, 26, and 27). In this context, cultural appropriateness refers to shared cultural experiences that can affect Black women’s risk for acquiring HIV. For example, SHIPS (No. 4) incorporated Black cultural messaging to increase learning about reducing unprotected sex. Project Ore (No. 7) addressed cultural issues through stimulating discussions about HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with DVD clips of interviews with youth to reinforce the concept of connectedness to friends and community with an African rite of passage exercise and ritual.

To better address factors related to HIV, five interventions used input from their target community (of Black women) for intervention development: Community Advisory Board (Nos. 10 and 19), Community Coalition Board (No. 12), Teen or Youth Advisory Board (Nos. 1 and 9). One intervention, SISTA (No. 5) was created to be culturally relevant and gender appropriate by (1) having the ability to be adapted across different organizational sites; (2) using Black women as peer leaders to lead the intervention; and (3) using culturally appropriate activities of games, role play, videos, and discussions about STIs. This particular intervention has also been adapted for different sub-populations of Black women, including for older Black women—Women to Women (W2W) (No. 26).

In addition, four interventions used community-based participatory research (CBPR) to develop or adapt the intervention (Nos. 10, 12, 22, and 23). In CBPR, diverse partners in the community are engaged (i.e., community engagement) to obtain and achieve multiple goals while addressing community-identified concerns [66]. For example, Project Thanks (No. 23) used CBPR to develop the intervention through focus groups to better understand how Black women defined, conceptualized, and interpreted their overall health status in the context of having a chronic illness concurrent with HIV. As a result, an “overall wellness” curriculum was developed to help women adopt healthy lifestyle behaviors to prevent risk associated with chronic disease, and substance abuse associated with HIV-related health complications. HIV-RAAP (HIV/AIDS Risk Reduction Among Heterosexually Active African American Men and Women; No. 12) also used CBPR with a culture and gender sensitive approach that involved a Community Coalition Board (CCB) to conduct a needs assessment to identify women’s health priorities and concerns (e.g., HIV/AIDS #1 health priority). The materials were then drafted, reviewed, and finalized by a panel of community and academic advisers that included African centered imagery and concepts. Staying true to CBPR, the CCB was actively involved throughout all stages of intervention development and delivery.

Outcomes of HIV/AIDS Prevention Interventions

Intervention effects were stratified and described based on the serostatus of each intervention’s sample population. Among interventions for HIV-negative Black women (n = 15), eleven intervention effects were identified (see Table 1). Of which, a number of the interventions focused on decreasing women’s engagement in unprotected sex or increasing their use of condoms (n = 12; Nos. 1–9, 11, and 14–15), increasing their knowledge on HIV/AIDS or STIs (in general) (n = 6; Nos. 1–3, 7, 8, 10), and reducing their use of substances with sex (i.e., alcohol or drug related risky sexual behaviors) (n = 7; Nos. 3, 5, 8–10, 13, and 14). Among interventions focusing on BWLWH (n = 10), seven intervention effects were identified across interventions (see Table 2). At least half of these interventions decreased unprotected sex or increased condom use (n = 5, Nos. 18, 20–24); increased one’s ability to communicate regarding disclosure of their HIV status, risk reduction strategies, or social support (n = 6); and addressed psychosocial mediators of self-efficacy (n = 5) (see Table 2). Among interventions that included both HIV-negative women and WLWH (n = 3), ten intervention effects were identified across interventions (see Table 3). For example, two interventions decreased unprotected sex or increased condom use (Nos. 27 and 28), and two interventions increased HIV/AIDS or STI knowledge (Nos. 26 and 27).

None of the interventions included in the current review incorporated PrEP, nPEP, or TasP.

Theoretical Frameworks, Models, and Approaches Used for Intervention Development

Social cognitive theory (n = 10) and theory of gender and power (n = 10) were the most used frameworks for intervention development (see Table 4; Fig. 2). Eighteen interventions incorporated two or more theories, models, or approaches (Nos. 1, 3–6, 8, 9, 11–14, 17, 18, 21–27), whereas 6 interventions used one theoretical framework, model, or approach (Nos. 7, 10, 15, 16, 19, 20). Three interventions used theories that were specifically created for use among Black individuals: (1) Nguzo Saba (No. 12), (2) NTU (No. 12), and (3) Black Feminist Theory (Nos. 9 and 10).

Africentric perspectives, such as Nguzo Saba and NTU (i.e., the essence of life) [67] are used within HIV-RAAP (No. 12) to support the premise that Black individuals are “interconnected communally and influenced by community decisions and lessons to be learned [68].” Africentrism refers to African influences on Black culture, consciousness, behavior, and social organization [68, 69]. According to Patricia Hill Collins [69], Afrocentric analyses implies that people of African descent created and re-created a valuable system of ideas, social practices, and cultures that have been essential to Black survival. Nguzo Saba principles, also known as Kwanzaa, uses African culture-infused principles of Umoja-unity, Kujichagulia-self-determination, Ujima-collective work and responsibility, Ijama-cooperative economics, Nia-purpose, Kuumba-creativity, and Imani-faith, and was specifically used to aid in discussions and activities throughout the seven-session curriculum of HIV-RAAP (No. 12) [67, 68]. Black feminist theory (BFT) aims to address and articulate the intersectional relationship of social, political, and economic issues (i.e., racism and sexism) within the lives and experiences of women of the African diaspora, while also creating space for Black women to consider their own experiences [69,70,71,72]. Thus, Black women learn to perceive the world and themselves from the perspective of their social group, also accounting for how they are perceived in the U.S. in a historical context. Through BFT, Black women can become empowered through consciousness changing in communities, and by taking steps to transform social institutions and inequalities [70, 71]. Wechsburge and colleagues (No. 9) used BFT to guide the adaptation of Young Women’s CoOp across multiple HIV vulnerable female populations (e.g., substance using Black women), both internationally [73,74,75] and in the U.S.[76]. Alternatively, Rountree and colleagues (No. 10) used BFT to guide the cultural development of their intervention to address HIV prevention needs of Black women who have experienced IPV.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current review is the first to summarize HIV/AIDS prevention interventions developed for Black, heterosexual women in the U.S. (specific to our inclusion criteria). Forty articles representing 28 interventions were included in this review. Fifteen interventions were created for HIV-negative Black women, ten interventions were created for BWLWH, and 3 interventions included both BWLWH and HIV-negative Black women. Of interest, 70% of included interventions were conducted in the South—a region where Black women are disproportionately affected by HIV. Though more efforts are needed to continue to decrease HIV incidence rates among Black women in this region, this finding highlights the continued effort to help improve HIV prevention efforts for this population. Additionally, no intervention focused on injection drug use as an outcome measure. Though substance abuse is an important contributing risk factor regarding heterosexual transmission of HIV and STIs among women [1, 2, 77,78,79], prior research has stated, “women who use and inject drugs remain underrepresented in many drug trials, studies, and hence in systematic review (78),” evident in the current findings. As such, there may be a need to expand current prevention interventions to identify not only substance-using Black women, but those who primarily inject drugs who need additional support and access to care. Furthermore, the current review highlights three main observations regarding biomedical prevention strategies, addressing different sub-groups of Black, heterosexual women, and the option of allowing participants to involve their sexual/romantic partners in the intervention.

Effective Biomedical Prevention Strategies

None of the interventions in the current review included newer biomedical strategies of PrEP, nPEP, and TasP for HIV prevention. An additional online search (not included in the review) was conducted to determine if any of the 28 interventions had biomedical components (e.g., PrEP, nPEP, TasP) that were not described in their academic articles. One intervention, Sister to Sister (No. 20), included an online factsheet (revised March of 2017) on guidelines for PrEP and nPEP use in the intervention’s program materials (see Appendix B) [80]. Improvement of HIV prevention efforts with Black women will require the use of both behavioral and biomedical (e.g., PrEP, nPEP, TasP) approaches.

Both PrEP and nPEP aim to prevent HIV acquisition among HIV-negative individuals. While nPEP is for HIV-negative individuals believed to have been exposed to HIV (e.g., unprotected sexual intercourse or injection drug use) [41, 81], PrEP is for individuals who are HIV-negative and at high-risk for acquiring HIV [42, 82]. PrEP, in particular, has the potential to empower Black women to be autonomous about their sexual health and HIV prevention options [42, 82, 83]. Both nPEP and PrEP can be used without a partner’s knowledge or consent, which may be important for and appealing to Black women: across the age continuum; with varying types of relationships; at risk for IPV [84]; who may face challenges with negotiating safer sex practices with their partners. At present, PrEP and nPEP are currently underutilized by Black women, which may be partially explained by their low awareness about these strategies as noted by one review on PrEP awareness [85]. TasP [43, 44, 86] is another effective biomedical strategy for HIV prevention that is often implemented by community-based organizations and healthcare professionals through engagement in HIV care. The effectiveness of TasP centers on maintaining adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among PLWH to ensure their viral loads remain undetectable to prevent onward transmission [43, 86, 87]. In addition to addressing the importance of adherence to ART, broader awareness about TasP may help decrease HIV-related stigma and improve support toward engaging and remaining in HIV care among BWLWH.

Toward the goal of reducing HIV incidence and HIV-related disparities among Black women in the U.S., current and future HIV prevention interventions ought to include content, activities, and mechanisms to access nPEP, PrEP, and ART for TasP. The inclusion of all available biomedical strategies in interventions, regardless of Blacks women’s HIV serostatus, may be beneficial as it could help improve broader awareness and uptake, as well support for using such methods. Findings from the systematic review also highlighted that additional HIV prevention interventions may be needed to address the needs of adolescent and older Black women, in addition to those with sexual/romantic relationship partners.

Adolescent Females

Five of the 28 interventions included in the review focused on adolescent, HIV-negative females (Nos. 1, 7, 9, 14, and 15). In 2017, the prevalence of HIV among adolescents aged 13 to 19 years in the U.S. was 8.1 per 100,000 [3]. There were 1060 Black adolescents diagnosed with HIV, and 128 diagnosed with AIDS [3]. Many adolescents engage in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., multiple sexual partners, condomless sex), which increases their risk for acquiring or transmitting HIV and other STIs [88]. Adolescents living with HIV are also less likely to be linked to care compared to other age groups [88]. Although the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for 2020 has indicated individuals aged 13 to 24 years as a target group for reducing new HIV infections [89], few interventions were created for adolescents as evident in our findings. Tailoring future interventions to address the HIV prevention and treatment needs of Black adolescent females may help improve HIV-related outcomes in this sub-group of women.

Older Women

Interventions developed for Black women who are 45 years of age and older were uncommon in the published literature, as noted by the 3 interventions identified in this review (Nos. 22, 23, and 26). Two of the interventions included BWLWH (Nos. 22 and 23) whereas the other intervention included Black women of both HIV serostatuses (No. 26). Recent reports show an increase in HIV diagnoses among older adults, with adults between 45 and 49 years having a rate of 14.1 per 100,000; and adults between 50 and 54 years having a rate of 12.5 per 100,000 [90]. Compared to younger individuals, older adults are more likely to have late stage HIV infection at the time of diagnosis [61, 91], are less likely to be assessed for STIs due to ageism [61], often have misconceptions about the absence of STIs, and are more likely to refuse discussing HIV due to fear of stigma [91]. Older adults are also at increased risk of acquiring HIV due to engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse, lacking HIV prevention knowledge, and having low self-perceived risk for HIV [61, 92]. Co-morbid conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer in addition to accelerated aging caused by HIV can provide further complications for older WLWH [93]. As such, additional HIV/AIDS prevention interventions may be needed to address these specific needs of aging Black women.

Women and Their Partner(s)

In the current review, none of the included interventions were designed for nor included Black women and their sexual and/or romantic relationship partner(s). Women’s HIV-related sexual risk behaviors (e.g., condomless intercourse) are dyadic in nature. Women in relationships are at increased risk for HIV when one or both partners have more than one sexual partner, condoms are rarely or not at all used, and/or when IPV occurs [94, 95]. Although couples-based approaches to HIV prevention are available and can help address the specific vulnerability and exposure women face regarding their gender roles, culturally and biologically [96,97,98], these interventions may have limitations. For example, women may not be given the autonomy to choose which sexual partner(s) to include and involve in their sexual health decision-making, as well as the level of involvement they would want their partner to have with them in the intervention. Also, the various dyadic types of sexual and/or romantic relationships that women may have are often not fully considered in the context of couples-based interventions. According to Karney et al. [99], “a dyadic perspective on HIV-prevention is not the same as a relationship perspective. All relationships are dyadic, but not all dyads are relationships…Within a dyadic perspective, there can be a continuum of involvement and influence ranging from superficial (one-time encounters) to enduring (long-term relationships).” Thereby, the incorporation of a dyadic perspective for future HIV/AIDS prevention interventions may help further our understanding of Black women’s differing relationship contexts and their associated needs relative toward having interventions tailored to better meet their desired involvement and inclusion of sexual and/or romantic partner(s). Use of a dyadic perspective could also help illuminate what relational interactions, types and other qualities affect Black women’s HIV prevention and treatment needs and associated outcomes.

Limitations

Limitations to this review exist. While it is believed the current review was exhaustive, the search terms used for each database may have excluded words that could have been useful in finding additional interventions that focused on HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for Black women in the U.S. A librarian was consulted to elicit search terms that could be useful across the various databases. Due to the overlap of interventions found across databases and the data extraction strategies used, it is unlikely that many interventions were missed. To provide an overview of interventions for Black women in the U.S. with published results on efficacy, the current review did not include on-going research studies found in online databases, such as Federal RePORTER (https://feder alreporter.nih.gov/) or Clinical Trials (https://ClinicalTrials.gov). It is possible some on-going studies could include a predominant sample of Black, heterosexual women, inclusive of any of the aforementioned subgroups, and are using biomedical strategies for HIV prevention. The present review further focused on interventions that either solely included or had a sample population of at least 50% heterosexual Black women, excluding the one intervention that was included. Interventions with sample populations substantially less than 50% Black women may have had different or similar findings than what is reported in this review. Differentiation between African Diasporas (i.e., African, Caribbean, Jamaican, Haitian, etc.) was also not done. Some HIV/AIDS prevention interventions may be differently effective for different populations of Black women in the U.S. relative to their African Diaspora. Further, the current review did not include interventions designed for Black, heterosexual women with a previous or current history of criminal justice involvement and/or incarceration, including prison. As noted in prior research [55, 56, 100, 101], women with recent or current involvement with the criminal justice system (i.e., incarcerated in state or federal prison) may need different approaches for HIV prevention, particularly within a prison setting, than what interventions in this review included. Due to these potential differences, a systematic review is warranted to examine the specific and unique HIV prevention needs of Black, heterosexual women who are or have been involved with the criminal justice system.

Conclusion

In light of these limitations, the current review identified and described the characteristics of 28 HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for Black, heterosexual women in the U.S., accompanied with providing relevant recommendations to help improve HIV/AIDS prevention efforts for this population. There is an urgent and compelling need to reduce HIV-related disparities among Black, heterosexual women in the U.S. While notable HIV/AIDS prevention interventions have been designed to address factors related to HIV among Black women, findings highlight opportunities to improve HIV/AIDS prevention efforts with this population. Incorporating newer biomedical strategies for HIV prevention and increasing prevention efforts among certain subpopulations of at-risk heterosexual Black women may help further decrease HIV incidence rates and onward HIV transmission.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (updated), vol 31. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published May 2020. Accessed May 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among women (updated 19 March 2019). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/gender/women/cdc-hiv-women.pdf. Accessed June 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017, vol 29. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published Nov 2018. Accessed Jan 2019.

Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Adimora AA. Sexual mixing patterns and heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans in the southeastern United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(1):114–20.

Harawa N, Adimora A. Incarceration, African Americans and HIV: advancing a research agenda. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(1):57–62.

Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, Wang L, Liu TY, Mayer KH. The high prevalence of incarceration history among Black men who have sex with men in the United States: associations and implications. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):448–54.

Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Blankenship KM. Associations of sex ratios and male incarceration rates with multiple opposite-sex partners: potential social determinants of HIV/STI transmission. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):70–80.

Seth PWT, Hollis N, Figueroa A, Belcher L. HIV Testing and service delivery among Blacks or African Americans—61 Health Department Jurisdictions, United States, 2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(4):87–90.

Jennings L, Rompalo AM, Wang J, Hughes J, Adimora AA, Hodder S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of knowledge of male partner HIV testing and serostatus among African-American women living in high poverty, high HIV prevalence communities (HPTN 064). AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):291–301.

Bachanas P, Medley A, Pals S, Kidder D, Antelman G, Benech I, et al. Disclosure, knowledge of partner status, and condom use among HIV-positive patients attending clinical care in Tanzania, Kenya, and Namibia. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(7):425–35.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2230–7.

Blackstock OJ, Frew P, Bota D, Vo-Green L, Parker K, Franks J, et al. Perceptions of community HIV/STI risk among US women living in areas with high poverty and HIV prevalence rates. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):811–23.

Aral SO, Adimora AA, Fenton KA. Understanding and responding to disparities in HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in African Americans. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):337–40.

Aaron E, Blum C, Seidman D, Hoyt MJ, Simone J, Sullivan M, et al. Optimizing delivery of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for women in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(1):16–23.

Wingood GM, Dunkle K, Camp C, Patel S, Painter JE, Rubtsova A, et al. Racial differences and correlates of potential adoption of preexposure prophylaxis: results of a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S95–S101.

Caiola C, Barroso J, Docherty SL. Black mothers living with HIV picture the social determinants of health. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29(2):204–19.

The Center for HIV Law and Policy. Women/women’s resource advocacy connection. https://www.hivlawandpolicy.org/issues/womenwomens-resource-advocacy-connection. Accessed Feb 2019.

Geter A, Sutton MY, Hubbard MD. Social and structural determinants of HIV treatment and care among black women living with HIV infection: a systematic review: 2005–2016. AIDS Care. 2018;30(4):409–16.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and African Americans 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html. Accessed Feb 2020.

McLean CP, Fitzgerald H. Treating posttraumatic stress symptoms among people living with HIV: a critical review of intervention trials. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(9):83.

Wagner AC, Jaworsky D, Logie CH, Conway T, Pick N, Wozniak D, et al. High rates of posttraumatic stress symptoms in women living with HIV in Canada. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7):e0200526.

Ojikutu B, Nnaji C, Sithole J, Schneider KL, Higgins-Biddle M, Cranston K, et al. All Black people are not alike: differences in HIV testing patterns, knowledge, and experience of stigma between US-born and non-US-born Blacks in Massachusetts. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(1):45–544.

Crockett KB, Edmonds A, Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Kempf MC, Konkle-Parker D, et al. Neighborhood racial diversity, socioeconomic status, and perceptions of HIV-related discrimination and internalized HIV stigma among women living with HIV in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(6):270–81.

Travaglini LE, Himelhoch SS, Fang LJ. HIV stigma and its relation to mental, physical and social health among Black women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(12):3783–94.

Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health (2002). 2011;20(7):991–1006.

Morales-Alemán MM, Hageman K, Gaul ZJ, Le B, Paz-Bailey G, Sutton MY. Intimate partner violence and human immunodeficiency virus risk among Black and Hispanic women. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):689–702.

Seth P, Wingood G, Robinson L, Raiford J, DiClemente R. Abuse impedes prevention: the intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV/STI risk among young African American Women. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1438–45.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in Southern United States 2016 (updated May 2016). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf. Accessed Nov 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States by geography 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/geographicdistribution.html. Accessed Nov 2019.

Reif S, Whetten K, Wilson E. HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the south reaches crisis proportions in last decade. Durham: Duke Center for Health Policy and Inequalities Research; 2011.

Ware S, Thorpe S, Tanner AE. Sexual health interventions for Black women in the United States: a systematic review of literature. Int J Sex Health. 2019;31(2):1–20.

Lennon CA, Huedo-Medina TB, Gerwien DP, Johnson BT. A role for depression in sexual risk reduction for women? A meta-analysis of HIV prevention trials with depression outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(4):688–98.

Rapid Response Service. Community-based interventions to increase HIV testing among Black women. In: Toronto OOHTN, 2016.

Hendrick CE, Canfield C. HIV Risk-reduction prevention interventions targeting African American adolescent women. Adolesc Res Rev. 2017;2(2):131–49.

Loutfy M, Tharao W, Logie C, Aden MA, Chambers LA, Wu W, et al. Systematic review of stigma reducing interventions for African/Black diasporic women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):19835.

Ruiz-Perez I, Murphy M, Pastor-Moreno G, Rojas-Garcia A, Rodriguez-Barranco M. The effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions in socioeconomically disadvantaged ethnic minority women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):e13–e21.

Tufts KA, Johnson KF, Shepherd JG, Lee JY, Ajzoon MSB, Mahan LB, et al. Novel interventions for HIV self-management in African American Women: a systematic review of mHealth interventions. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(2):139–50.

Franconi I, Guaraldi G. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection in the older patient: what can be recommended? Drugs Aging. 2018;35(6):1–7.

Padian NS, Buve A, Balkus J, Serwadda D, Cates W Jr. Biomedical interventions to prevent HIV infection: evidence, challenges, and way forward. Lancet. 2008;372(9638):585–99.

AVERT. HIV prevention programs overview (updated 13 June 2017). https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-programming/prevention/overview. Accessed Oct 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PEP 2018 (15 Jan 2018). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/pep.html. Accessed July 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) 2017 (updated 31 Aug 2017). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html. Accessed Sept 2018.

Williams B, Wood R, Dukay V, Delva W, Ginsburg D, Hargrove J, et al. Treatment as prevention: preparing the way. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14(Suppl 1):S6.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV treatment as prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html. Accessed Nov 2019.

Masur H, Brooks JT, Benson CA, Holmes KK, Pau AK, Kaplan JE. Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: updated guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(9):1308–11.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV treatment (updated 17 Oct 2019). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/livingwithhiv/treatment.html. Accessed Nov 2019.

Purcell DW, Mizuno Y, Smith DK, Grabbe K, Courtenay-Quick C, Tomlinson H, et al. Incorporating couples-based approaches into HIV prevention for gay and bisexual men: opportunities and challenges. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):35–46.

Leblanc NM, Mitchell J. Providers’ perceptions of couples’ HIV testing and counseling (CHTC): perspectives from a US HIV epicenter. Couple Fam Psychol. 2018;7(1):22–33.

World Health Organization. Guidance on couples HIV testing and counselling including antiretroviral therapy for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

Farley JL, Mitty JA, Lally MA, Burzynski JN, Tashima K, Rich JD, et al. Comprehensive medical care among HIV-positive incarcerated women: the Rhode Island experience. J Womens Health Gend Base Med. 2000;9(1):51–6.

Altice FL, Marinovich A, Khoshnood K, Blankenship KM, Springer SA, Selwyn PA. Correlates of HIV infection among incarcerated women: implications for improving detection of HIV infection. J Urban Health Bull NY Acad Med. 2005;82(2):312–26.

Talvi SJ. Women behind bars: the crisis of women in the US prison system. Emeryville: Seal Press; 2007.

Unodc I, Undp W, Unaids H. HIV prevention, treatment and care in prisons and other closed settings: a comprehensive package of interventions. Vienna: United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime; 2013. Accessed Nov 2019

Johnson ME, Kondo KK, Brems C, Eldridge GD. HIV/AIDS research in correctional settings: a difficult task made even harder? J Correct Health Care. 2015;21(2):101–11.

Strathdee SA, West BS, Reed E, Moazen B, Azim T, Dolan K. Substance use and HIV among female sex workers and female prisoners: risk environments and implications for prevention, treatment, and policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 2(0 1)):S110–S11717.

Westergaard RP, Spaulding AC, Flanigan TP. HIV among persons incarcerated in the USA: a review of evolving concepts in testing, treatment, and linkage to community care. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(1):10–6.

Binswanger IA, Merrill JO, Krueger PM, White MC, Booth RE, Elmore JG. Gender differences in chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance-dependence disorders among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):476–82.

Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper GW. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3):230–6.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and transgender people. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html. Accessed Nov 2019.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among people aged 50 and over (updated 12 Feb 2018). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html. Accessed Nov 2019.

Rountree MA, Bagwell M, Theall K, McElhaney C, Brown A. Lessons Learned: exploratory study of a HIV/AIDS prevention intervention for African American women who have experienced intimate partner violence. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2014;7:24–46.

Turan B, Rice WS, Crockett KB, Johnson M, Neilands TB, Ross SN, et al. Longitudinal association between internalized HIV stigma and antiretroviral therapy adherence for women living with HIV: the mediating role of depression. AIDS (Lond Engl.). 2019;33(3):571–6.

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, Browning WR, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):283–91.

Wenzel SL, Cederbaum JA, Song A, Hsu HT, Craddock JB, Hantanachaikul W, et al. Pilot test of an adapted, evidence-based HIV sexual risk reduction intervention for homeless women. Prev Sci. 2016;17(1):112–21.

Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011.

Foster PM, Phillips F, Belgrave FZ, Randolph SM, Braithwaite N. An Africentric model for AIDS education, prevention, and psychological services within the African American community. J Black Psychol. 1993;19(2):123–41.

Yancey EM, Mayberry R, Armstrong-Mensah E, Collins D, Goodin L, Cureton S, et al. The community-based participatory intervention effect of “HIV-RAAP”. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(4):555–68.

Collins PH. Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge; 2002.

Simien EM. Black feminist theory. Women Polit. 2004;26(2):81–93.

Simien EM, Clawson RA. The intersection of race and gender: an examination of Black feminist consciousness, race consciousness, and policy attitudes. Social Sci Q. 2004;85(3):793–810.

Opara I. Examining African American parent–daughter HIV risk communication using a Black feminist-ecological lens: implications for intervention. J Black Stud. 2018;49(2):134–51.

Wechsberg WM, Jewkes R, Novak SP, Kline T, Myers B, Browne FA, et al. A brief intervention for drug use, sexual risk behaviours and violence prevention with vulnerable women in South Africa: a randomised trial of the Women’s Health CoOp. BMJ Open. 2013;3(5):e002622.

Wechsberg WM, Krupitsky E, Romanova T, Zvartau E, Kline TL, Browne FA, et al. Double jeopardy—drug and sex risks among Russian women who inject drugs: initial feasibility and efficacy results of a small randomized controlled trial. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7(1):1.

Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Kline TL, Browne FA, Zule WA. Preliminary findings of an adapted evidence-based woman-focused HIV intervention on condom use and negotiation among at-risk women in Pretoria, South Africa. J Prev Interv Community. 2010;38(2):132–46.

Wechsberg WM, Lam WK, Zule WA, Bobashev G. Efficacy of a woman-focused intervention to reduce HIV risk and increase self-sufficiency among African American crack abusers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1165–73.

Des Jarlais DC, McCarty D, Vega WA, Bramson H. HIV infection among people who inject drugs: the challenge of racial/ethnic disparities. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):274–85.

El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA. Women who use or inject drugs: an action agenda for women-specific, multilevel, and combination HIV prevention and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2015;69(Suppl 2):S182–S190190.

Iversen J, Page K, Madden A, Maher L. HIV, HCV, and health-related harms among women who inject drugs: implications for prevention and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2015;69(Suppl 2 (0 1)):S176–S181181.

Sister to sister: a brief skills-based HIV risk-reduction program for women in primary health care clinics FACT SHEET. 2017. https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/docs/default-source/sister-to-sister/s2s-core-elements-fact-sheet/sister-to-sister-fact-sheet.pdf?sfvrsn=9f0932d3_2. Accessed Nov 2019.

Mitchell JW, Sophus AI, Petroll AE. HIV-negative partnered men’s willingness to use non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis and associated factors in a U.S. sample of HIV-negative and HIV-discordant male couples. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):146–52.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service; 2018. Accessed Jan 2018.

Raifman J, Sherman SGUS. guidelines that empower women to prevent HIV with pre-exposure prophylaxis: women and PrEP guidelines. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(6):e38–e3939.

Braksmajer A, Senn TE, McMahon J. The potential of pre-exposure prophylaxis for women in violent relationships. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(6):274–81.

Sophus AI, Mitchell JW. A review of approaches used to increase awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(7):1749–70.

Holmes CB, Hallett TB, Wilensky R, Bärnighausen T, Pillay Y, Cohen MS. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatment as prevention for HIV. In: Major infectious diseases, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017.

Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13:35.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth (updated 12 Nov 2019). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html. Accessed Nov 2019.

White House. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020. White House; 2017. Accessed Nov 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Preliminary), vol. 30 (published Nov 2019). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed May 2020.

Roberson DW. Meeting the HIV prevention needs of older adults. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29(1):126–9.

Smith TK, Larson EL. HIV sexual risk behavior in older Black women: a systematic review. Women’s Health Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Women’s Health. 2015;25(1):63–72.

Warren-Jeanpiere L, Dillaway H, Hamilton P, Young M, Goparaju L. Taking it one day at a time: African American women aging with HIV and co-morbidities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(7):372–80.

Wingood GM, Camp C, Dunkle K, Cooper H, DiClemente RJ. HIV prevention and heterosexual African-American women. In: HIV/AIDS in US communities of color. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 213–26.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):539–65.

El-Bassel N, Caldeira NA, Ruglass LM, Gilbert L. Addressing the unique needs of African American women in HIV prevention. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):996–1001.

El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, Hunt T, Remien RH. Couple-based HIV prevention in the United States: advantages, gaps, and future directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S98–S101.

El-Bassel N, Wechsberg WM. Couple-based behavioral HIV interventions: placing HIV risk-reduction responsibility and agency on the female and male dyad. Couple Fam Psychol. 2012;1(2):94.

Karney BR, Hops H, Redding CA, Reis HT, Rothman AJ, Simpson JA. A framework for incorporating dyads in models of HIV-prevention. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(Suppl 2):189–203.

Underhill K, Dumont D, Operario D. HIV prevention for adults with criminal justice involvement: a systematic review of HIV risk-reduction interventions in incarceration and community settings. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e27–e53.

Epperson MW, Khan MR, Miller DP, Perron BE, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L. Assessing criminal justice involvement as an indicator of human immunodeficiency virus risk among women in methadone treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38(4):375–83.

Funding

There is no funding attached to this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Amber I. Sophus declares that she has no conflict of interest. Jason W. Mitchell declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sophus, A.I., Mitchell, J.W. Reducing HIV Risk Behaviors Among Black Women Living With and Without HIV/AIDS in the U.S.: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav 25, 732–747 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03029-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03029-3