Abstract

Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) have disproportionate HIV/STI acquisition risk. Incarceration may increase exposure to violence and exacerbate psychosocial vulnerabilities, including internalized homophobia, which are associated with HIV/STI acquisition risk. Using data from HIV Prevention Trials Network 061 (N = 1553), we estimated adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between lifetime burden of incarceration and HIV/STI risk outcomes. We measured associations between incarceration and HIV/STI risk outcomes with hypothesized mediators of recent violence victimization and internalized homophobia. Compared to those never incarcerated, those with 3–9 or ≥ 10 incarcerations had approximately 10% higher prevalence of multiple partnerships. Incarceration burden was associated with selling sex (1–2 incarcerations: APR: 1.52, 95% CI 1.14–2.03; 3–9: APR: 1.77, 95% CI 1.35–2.33; ≥ 10: APR: 1.85, 95% CI 1.37–2.51) and buying sex (≥ 10 incarcerations APR: 1.80, 95% CI 1.18–2.75). Compared to never incarcerated, 1–2 incarcerations appeared to be associated with current chlamydia (APR: 1.47, 95% CI 0.98–2.20) and 3–9 incarcerations appeared to be associated with current syphilis (APR: 1.46, 95% CI 0.92–2.30). Incarceration was independently associated with violence, which in turn was a correlate of transactional sex. Longitudinal research is warranted to clarify the role of incarceration in violence and HIV/STI risk in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV persists as a critical public health priority, disproportionally impacting Black men who have sex with men (BMSM). Approximately one-third of BMSM are currently living with HIV and if these rates persist, projections suggest 50% will acquire HIV in their lifetime [1, 2]. Though BMSM report less drug use, fewer male sexual partners, and have comparable rates of unprotected anal intercourse than White MSM, they face a much greater risk of acquiring HIV [2, 3]. Other sexually transmitted infections (STI), including gonorrhea and syphilis, are also disproportionately more common among BMSM [4]. These infections can cause serious complications if left undetected and untreated and increase the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV [5, 6]. Given that individual-level drug and sex risk behaviors do not fully explain heightened infection risk among BMSM, there is a need to consider the potential importance of social and structural factors that may drive HIV/STI infection in this population.

Incarceration has consistently been associated with HIV/STI risk among heterosexual populations [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Though incarceration is prevalent among BMSM, with up to 60% having experienced incarceration in their lifetime [13,14,15], there has been little research examining its effects on HIV/STI risk specifically within this group. Extant studies on the relationship between incarceration and HIV/STI risk among MSM have been conducted primarily in non-generalizable samples (e.g., young MSM, specific geographic regions, those living with HIV) [16,17,18,19]. Extant studies often fail to estimate effects by race among MSM, despite evidence that the burden of incarceration is much higher for BMSM compared to White MSM [16, 18]. Within the studies that have done so, the findings regarding effects among BMSM are somewhat inconsistent. One study found that the interaction between Black race and history of incarceration was associated with increased HIV/STI risk behavior [16] while another found that White MSM had higher risk [18]. Finally, no known studies have examined lifetime cumulative number of incarcerations among BMSM rather than a dichotomous indicator of prior history. Considering that increasing number of incarceration events has demonstrated a dose–response relationship with HIV-related risk in other populations [20], there is a need to understand the total burden on incarceration among BMSM.

Incarceration may influence HIV/STI risk among BMSM by working through several pathways. HIV/STI may be transmitted during the incarceration [21] considering the high prevalence of untreated infections and same-sex segregation in correctional facilities [22]. As has been observed in heterosexual populations, incarceration disrupts social, sexual, and support networks as well as capital [23,24,25,26]. After release, network disruption may lead to new, multiple, and/or concurrent partnerships, proximate determinants of HIV/STI [27]. Reduced social capital and economic instability may also lead to other HIV/STI risk factors such as engagement in transactional sex, substance use, and depression [28, 29]; the relationships among incarceration and these factors may be bi-directional or cyclical, considering that transactional sex, substance use, and poor mental health may also lead to contact with the criminal justice system [30]. Because of the limited research on the role of incarceration on HIV/STI risk among BMSM, there is a need to examine this association in this population.

Two factors that may play a particularly important role in the relationship between incarceration and HIV/STI risk among BMSM are violence victimization [31, 32] and internalized homophobia [33], with high levels identified among BMSM [34], and which are strong correlates of HIV/STI risk [33, 35,36,37]. Incarceration may further exacerbate victimization among BMSM, with one in five individuals who are incarcerated reporting violence perpetrated by other inmates or correctional facility staff [38, 39]. Experiencing violence can result in emotional distress, difficulties adjusting to the community after release, greater risk of drug use and sexual risk behaviors, and sexual violence, leading directly to HIV/STI transmission [40,41,42,43,44]. Another potentially important pathway from incarceration to HIV/STI among BMSM may be internalized homophobia. Incarceration is stigmatizing [40] and stigma has been shown to inhibit the development of protective network ties, resulting in social isolation, emotional distress, depressive symptoms, and HIV/STI-related infection transmission [41,42,43]. Groups that are already highly stigmatized, such as racial and sexual and gender minorities, may be particularly vulnerable to internalizing stigma due to their incarceration [44] and homophobic attitudes within correctional facilities [45,46,47,48]. However, research on the interplay between incarceration, social/structural factors (i.e., violence and internalized homophobia), and HIV/STI risk has been limited.

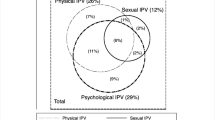

The purpose of the current study is to address a gap in the extant literature by measuring associations between the lifetime burden of incarceration and HIV/STI risk among BMSM. We used baseline data from The HIV Prevention Trials Network 061 Study (HPTN 061; the Brothers Study) to measure cross-sectional associations between lifetime number of incarcerations, HIV/STI risk indicators including sexual risk behaviors, and STI infection. Given the potential for incarceration-related increases in victimization and stigmatization that may translate to HIV/STI-related risk-taking, we also examined associations between incarceration and hypothesized mediators of violence and internalized homophobia as well as associations between these factors and other HIV/STI risk factors (Fig. 1).

Methods

Sample

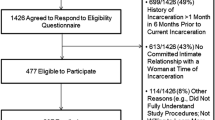

The parent study’s enrollment and recruitment methods have been comprehensively described elsewhere [49]. In brief, HPTN 061 was conducted to test the feasibility and efficacy of a peer-health navigation intervention to prevent the acquisition and transmission of HIV among BMSM. Enrollment occurred from 2009 to 2010 in six metropolitan cities in the United States (US): Atlanta, New York City, Washington DC, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston. Institutional review boards (IRB) at the participating institutions approved the study; NYU School of Medicine considers secondary analysis of de-identified data to be non-human subjects’ research and thus did not require IRB review. HPTN 061 enrolled 1553 participants at least 18 years of age who identified as a man or male at birth; identified as Black, African American, Caribbean, African or multi-ethnic Black; and who reported at least one instance of condomless sex with a man in the past 6 months. Participants completed an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) survey that assessed demographic information, HIV risk behaviors, experiences of violence, and internalized homophobia. They also provided specimens for HIV/STI testing. Of the 1553 enrolled in the study, 252 participants reported a prior HIV diagnosis and 95 were diagnosed with HIV at enrollment; our analyses were restricted to 1521 participants who responded to the incarceration question at baseline.

Measures

Exposure: Incarceration

Participants were asked: “How many times in your life have you spent 1 or more days in jail or prison?” We then categorized incarceration frequency into a four-level variable (never, 1–2 times, 3–9 times and ≥ 10 times).

Outcomes: HIV/STI Risk Behaviors and STI Infection

Multiple Partnerships

Participants reported the number of sexual partnerships in the past 6 months and those reporting three or more partners (i.e., the median in the sample) were categorized as having multiple partnerships.

Transactional Sex

Participants reported if they had given or received money from male sex partners in the past 6 months. Buying sex was defined as having given money, goods, or items in exchange for sex and selling sex was defined as having received money, goods, or items in exchange for sex.

Condomless anal Intercourse

We measured whether participants had engaged in condomless receptive anal intercourse in the past 6 months (i.e., as a bottom). Among participants who were HIV negative, we also assessed any condomless receptive anal intercourse with partners whom the participants reported to be HIV positive or whose HIV status was unknown.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Urine and rectal swabs were collected to test for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Hologic Gen Probe Aptima Combo 2, San Diego, CA) at the HPTN Laboratory Center. A blood specimen was collected for Treponema pallidum testing at local laboratories.

Hypothesized Mediating Factors: Internalized Homophobia and Violence

Internalized Homophobia

Internalized homophobia at baseline was assessed using a 7-item scale adapted from Herek and Glunt [50] measuring how strongly participants agreed or disagreed with statements describing how they felt in the past 90 days, such as: “I wish I weren’t attracted to men,” “I feel bad about being attracted to men because my community looks down on men who are,” and “As a Black man, I try to act more masculine to hide my sexuality.” The items were summed, with increasing scores indicating higher levels of internalized homophobia, which we then dichotomized at the median (scores ≥ 8; range 0–28) given there was a lack of linearity in the log odds with some outcomes.

Violence

Participants reported whether in the past 6 months any of the following three violent events occurred because of their race and/or sexuality: being punched, kicked, or beaten, having an object thrown at them; being threatened with physical violence; and being threatened with a knife, gun, or other weapon. Those who endorsed any of these violent experiences were coded as exposed to violence in the past 6 months (yes versus no).

Covariates

We included the following demographic and socio-economic confounders in multivariable models: categorical age (18–30 years, 31–50 years, and 51–70 years), since continuous age was not linear in the log odds of some outcomes; dichotomous past 6 month partnership history, categorized as Black men who have sex with men only (BMSMO) versus Black men who have sex with men and women (BMSMW); categorical site indicator (New York City, Washington DC, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Atlanta); dichotomous education variable indicating receipt of greater than a high school education (yes versus no); dichotomous functional poverty indicator defined as reporting insufficient income fairly often and very often versus never or once in a while; and categorical marital status indicator categorized as married/civil union/legal partnership, with a primary partner and cohabiting, with a primary partner and not cohabiting, and single/divorced/widowed.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted using R Version 3.5.1 “Feather Spray.”[51] We used modified Poisson regression with robust standard errors to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for associations between the number of times incarcerated and the HIV/STI-related sexual risk behavior and biologically-confirmed STI outcomes. Adjusted models controlled for sociodemographic factors including age, BMSMO/BMSMW status, study site, education, insufficient income, and marital status. We conducted similar analyses to estimate associations between frequency of incarceration and potential mediators of internalized homophobia and exposure to violence, as well as associations between the potential mediators and HIV/STI behavioral risk and STI infection outcomes.

Results

Sample Characteristics by Exposure to Violence and Internalized Homophobia

Of the analytic study sample (N = 1521), approximately 76% of participants were exposed to violence. Older participants reported instances of violence more frequently (31–50 [79.4%] and 51–70 [78.5%]) compared with younger men (18–30 [69.6%]; Table 1). The highest percentages of participants who experienced violence were from San Francisco (82.4%), followed by Los Angeles (79.4%), Boston (78.1%) and Atlanta (76.1%). Participants with lower education and income reported a higher prevalence of violence.

The prevalence of elevated internalized homophobia was approximately 1.8 times higher among BMSMW compared to BMSMO. Geographic differences were also observed, with participants in Boston (62.8%) reporting the highest prevalence of internalized homophobia, which was significantly higher compared to the referent city of New York. The prevalence of internalized homophobia was higher among participants with lower educational attainment and those reporting insufficient income. Compared to single/divorced/widowed participants, those who were married/in a civil union had approximately 1.4 times (95% CI 1.09–1.70) the prevalence of internalized homophobia. Though a larger proportion of participants aged 51–70 years had internalized homophobia compared to younger participants (54.7% vs 47.9%), the confidence intervals crossed the null and was not significant.

Frequency of Incarceration and HIV/STI-Related Sexual Risk Behaviors

Approximately 61% of participants reported having been incarcerated at least one time in their lives; 21% reported 1–2 incarcerations, 24% reported 3–9 incarcerations, and 15% reported ≥ 10 incarcerations (data not presented in tables). In the 6 months before the baseline interview, 75% reported multiple partnerships, 13% bought sex, 22% sold sex, and, among those reporting receptive anal sex in the past 6 months, 50% reported having had condomless receptive anal sex.

Incarceration was modestly associated with multiple partnerships (Table 2). In adjusted analyses, those incarcerated 3–9 times and those incarcerated ≥ 10 times had approximately 10% increased prevalence of multiple partnerships compared to those who had never been incarcerated (3–9 times APR: 1.11, 95% CI 1.03–1.20; ≥ 10 times APR: 1.10, 95% CI 1.01–1.19).

Increasing frequency of incarceration demonstrated a strong, approximately dose–response relationship with both buying and selling sex. In unadjusted analyses, those who were incarcerated ≥ 10 times had over two and half times the prevalence of buying sex (PR 2.58; 95% CI 1.76–3.79) and selling sex (PR 2.73; 95% CI 2.07–3.62) compared to those who were never incarcerated. Though these associations were attenuated in adjusted analyses, the dose–response relationships generally remained for both buying (1–2 times APR: 1.42, 95% CI 0.96–2.10; 3–9 times APR: 1.58, 95% CI 1.08–2.33; ≥ 10 times APR: 1.80, 95% CI 1.18–2.75) and selling sex (1–2 times APR: 1.52, 95% CI 1.14–2.03; 3–9 times APR: 1.77, 95% CI 1.35–2.33; ≥ 10 times APR: 1.85, 95% CI 1.37–2.51).

While a history of 10 or more incarcerations was associated with engaging in condomless receptive anal intercourse with an HIV-positive partner (PR 1.28 95% CI 1.00–1.64) in unadjusted analyses, the association was attenuated and non-significant after adjustment.

Frequency of Incarceration and STI

In unadjusted analyses, a history of 1–2 incarcerations or 3–9 incarcerations was not associated with a combined indicator of any STI (Table 2). When adjusting for covariates, compared to never being incarcerated, 1–2 incarcerations appeared to be associated with chlamydia (APR: 1.47, 95% CI 0.98–2.20) but not gonorrhea (APR: 1.24, 95% CI 0.71–2.15) or syphilis (APR: 1.18, 0.73–1.90), while 3–9 incarcerations appeared to be associated with syphilis (APR: 1.46, 95% CI 0.92–2.30) but not chlamydia (APR: 1.20, 95% CI 0.72–1.98) or gonorrhea (APR: 0.95, 95% CI 0.47–1.91). Those with ≥ 10 incarcerations appeared to have lower prevalence of each STI compared to those with no incarceration history (chlamydia: 0.44, 95% CI 0.22–0.87; gonorrhea: 0.07, 95% CI 0.01–0.51; syphilis: 0.53, 95% CI 0.27–1.02), but in adjusted analyses incarceration was not an independent correlate of infection.

Frequency of Incarceration and Hypothesized Mediators

Both before and after adjustment, incarceration was associated with increased experience of violence (1–2 times APR: 1.13, 95% CI 1.04–1.23; 3–9 times APR: 1.16, 95% CI 1.08–1.26; ≥ 10 times APR: 1.23, 95% CI 1.14–1.33; Table 3). In unadjusted models, having been incarcerated 3–9 times and ≥ 10 times were both significantly associated with elevated levels of internalized homophobia (APR: 1.23 95% CI 1.08–1.39 and APR: 1.27 95% CI 1.11–1:46, respectively), though in adjusted models these associations were reduced to null and no longer significant.

Hypothesized Mediators and HIV/STI-Related Sexual Risk Behavior and Infection

In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, violence exposure was associated with buying sex (APR: 1.50 95% CI 1.03–2.19) and selling sex (APR: 1.48 95% CI 1.14–1.92) but not with multiple partnerships or STI (Table 4). Internalized homophobia was not an independent correlate of risk behavior or infection in adjusted analyses, with the exception of a modest association with multiple partnerships (APR: 1.10, 95% CI 1.04–1.16).

Discussion

In this US sample of BMSM, history of incarceration and repeat incarcerations were common: sixty percent of the sample had been incarcerated at least once in their lifetime, as has been documented previously [14], and of those, many had cycled through the criminal justice system numerous times, with 24% reporting 3–9 prior incarcerations and 15% reporting 10 or more. Increasing exposure to incarceration was associated in a dose–response fashion with risk of transactional sex and also suggested low-level incarceration may be linked to elevations in chlamydia and moderate levels of incarceration were associated with syphilis. Our analyses also suggested that incarceration was associated with violence exposure, an established HIV/STI risk factor [36, 37]. Our findings are among the first to document associations between the cumulative burden of incarceration, sexual risk behaviors, and STI infection among BMSM, a population facing a disproportionately elevated risk of both HIV/STI and incarceration compared to the general population [1, 13, 14]. Future research using longitudinal data should measure the prospective relationships linking incarceration, violence, and HIV/STI risk and investigate mediating paths among these factors in this population.

To date, there is limited information about the relationships between incarceration and HIV/STI-related risk behaviors among BMSM [13, 16, 18, 52]. Most prior studies on the incarceration-HIV/STI link have been conducted in population-based samples composed largely of heterosexual populations [8, 9, 12, 53,54,55,56]. Findings from those studies suggest that incarceration is associated with 1.5–2 times greater likelihood of sexual risk behaviors including multiple and/or concurrent partnerships and buying and selling sex [57], and we likewise observed comparable relationships between incarceration and transactional sex in this sample of BMSM. Incarceration-related disruptions of networks including primary partnerships may result in buying sex after release from incarceration, while incarceration-related impacts on economic stability may result in selling sex, which may increase the risk of HIV/STI infection [8, 58]. We did not observe a strong association between incarceration and multiple partnerships as has been observed in primarily heterosexual samples [55, 56, 59, 60]. The extent to which incarceration may increase risk not only of high-risk sex such as transactional sex among BMSM, as well as elevations in partnership exchange rates, warrants further investigation.

Even prior to adjusting for covariates, STI prevalence was not higher among those with incarceration histories compared to those with no prior incarceration. In fact, we observed those with highest levels of repeat incarceration had consistently lower rates of STI, a finding that may reflect improved access to STI screening and treatment during incarceration compared to when in the community, and/or decreased access to new partners while incarcerated and decreased social mobility after incarceration [61]. It is also possible that individuals who cycle through jails and prisons frequently have higher levels of drug and sex risk-taking [55] and potentially greater perceived risk of infection, which may lead them to seek care. That said, in analyses adjusting for covariates, low and moderate incarceration levels appeared to be associated with a higher prevalence of STI and suggest that the experience of detainment and release may be linked among many involved in the criminal justice system to sexual risk-taking and also to increased risk of infection. Our results are aligned with a study conducted among young BMSM, which found that prior CJI was linked to better HIV care continuum metrics although frequent and cyclic CJI adversely impacted HIV care [62]. These findings underscore the importance of frequent STI screening for BMSM involved in the criminal justice system [63].

We hypothesized that violence and internalized homophobia may potentially link incarceration to HIV/STI risk. We did not observe an association between incarceration and internalized homophobia or between internalized homophobia and HIV/STI risk. The nature of this cross-sectional study may have precluded the ability to detect an association considering the incarceration may have occurred much earlier in a participant’s lifetime and their feelings of internalized homophobia measured at the time of this study have subsequently evolved. However, the elevated experience of violence, reported by over three-quarters of participants, demonstrated a modest dose–response relationship with increasing incarceration frequency. In turn, violence was linked to approximately 50% higher prevalence of transactional sex. Exposure to violence may increase HIV/STI risk by heightening a number of psychosocial factors (e.g., substance use, depression) that are also associated with sexual risk behaviors such as condomless sex, sex after drug use, and sex with multiple partners [64]. The already-prevalent experience of violence among BMSM in the community may be exacerbated by violence experienced within the criminal justice system [38, 39], considering that violence frequently co-occurs with high incarceration rates in communities where economic inequity and social disadvantages are high. Improving our understanding of the relationships among incarceration, violence, and HIV/STI risk is critical, as is preventing the unacceptably high levels of violence experienced by BMSM in general, particularly those who cycle through the criminal justice system.

Prevention efforts are needed to reduce the grossly disproportionate exposure to incarceration among Black men including BMSM in the US. In 2017, the rate of incarceration in the US dropped to its lowest level in 20 years yet a vast racial/ethnic disparity persists, and Black individuals are still approximately six times more likely to be imprisoned compared to White individuals [65]. Further, sexual minority individuals such as MSM have historically been overrepresented in the criminal justice system and therefore disproportionately exposed to violence therein [31], heightening the urgency for alternatives to incarceration, especially for this population. In addition to primary prevention efforts to reduce incarceration, HIV/STI prevention interventions tailored to BMSM impacted by the criminal justice system should be strengthened. Extant HIV/STI interventions for individuals involved in the criminal justice system are efficacious [66], though none are culturally tailored for MSM [67], let alone BMSM. A simulation study on the effects of a test, treat, retain, and condom use intervention for BMSM in the criminal justice system in Fulton County, Georgia, found that such an intervention strategy has the potential to substantially reduce HIV incidence, prevalence, and mortality among BMSM in jails and prisons as well as those within the community [68]. However, to inform the development of similar interventions that are tailored and target the salient factors for this population, we must continue to examine the pathways linking incarceration to HIV/STI risk for BMSM.

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. Cross-sectional data present challenges when making inferences. We are unable to determine the temporal relationships between incarceration and the outcomes, and there is potential for reverse causality. For example, individuals who engage in transactional sex may be more likely to come in contact with the police and be incarcerated; while we do not know where the transactional sex occurred, it was common to meet sex partners, including transactional partners, in public places within studies conducted around the same period as HPTN 061, which could increase risk of encountering police [69, 70]. The issue of temporality may be especially important for the measure of STI; even if incarceration did precede STI acquisition, the infection could have been treated and hence we did not detect an association. Future analyses with longitudinal data would allow for more rigorous assessment of temporality among these indicators. The self-reported measures are vulnerable to social desirability and recall bias, particularly for potentially highly stigmatized factors such as incarceration and sexual behavior. Although these data represent a large sample from diverse regions of the US, the current findings may not be generalizable to all BMSM and recruitment and context differ across the six cities included in this study. Incarceration was measured by participants’ response to a question asking how many times in their lifetime they had spent one or more nights in jail/prison, but given the range of reported number of incarcerations (from one to as many as > 300 times), it is possible that a small number of participants misinterpreted the question and reported the total number of nights they had been incarcerated in their lifetime.

This study contributes to and strengthens emerging evidence documenting the detrimental effects of incarceration, which unduly impacts already marginalized and vulnerable groups including BMSM. Our findings highlight that the epidemics of incarceration and HIV/STI among BMSM are interconnected and may be exacerbated by violent experiences. Preventing criminal justice involvement and mitigating its negative effects are crucial and may be a promising means of reducing HIV/STI risk among BMSM.

References

Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, Kelley R, Johnson K, Montoya D, et al. HIV among Black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):10–25.

Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS (London, England). 2007;21(15):2083–91.

Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL, Wilson PA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STDS in men who have sex with men 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/msm.htm.

Cohen MS. HIV and sexually transmitted diseases: lethal synergy. Top HIV Med. 2004;12(4):104–7.

Cohen MS. Classical sexually transmitted diseases drive the spread of HIV-1: back to the future. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):1–2.

Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, Ndeffo-Mbah M, Galvani A, Kinner SA, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. Lancet (London, England). 2016;388(10049):1089–102.

Khan MR, Miller WC, Schoenbach VJ, Weir SS, Kaufman JS, Wohl DA, et al. Timing and duration of incarceration and high-risk sexual partnerships among African Americans in North Carolina. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(5):403–10.

Khan MR, Golin CE, Friedman SR, Scheidell JD, Adimora AA, Judon-Monk S, et al. STI/HIV sexual risk behavior and prevalent STI among incarcerated African American men in committed partnerships: the significance of poverty, mood disorders, and substance use. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1478–90.

Adams JW, Lurie MN, King MRF, Brady KA, Galea S, Friedman SR, et al. Potential drivers of HIV acquisition in African-American women related to mass incarceration: an agent-based modelling study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1387.

Hearn LE, Whitehead NE, Khan MR, Latimer WW. Time since release from incarceration and HIV risk behaviors among women: the potential protective role of committed partners during re-entry. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1070–7.

Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, Tisdale C, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and associations with post-release STI/HIV risk behavior in a Southeastern city. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(1):43–7.

Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, Wang L, Liu TY, Mayer KH. Exploring the relationship between incarceration and HIV among black men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(2):218–25.

Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, Wang L, Liu TY, Mayer KH. The high prevalence of incarceration history among Black men who have sex with men in the United States: associations and implications. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):448–54.

Wilson PA, Nanin J, Amesty S, Wallace S, Cherenack EM, Fullilove R. Using syndemic theory to understand vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Latino men in New York City. Journal of Urban Health. 2014;91(5):983–98.

Phillips G 2nd, Birkett M, Salamanca P, Ryan D, Garofalo R, Kuhns L, et al. Interplay of race and criminal justice involvement on sexual behaviors of young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(2):197–204.

Philbin MM, Kinnard EN, Tanner AE, Ware S, Chambers BD, Ma A, et al. The association between incarceration and transactional sex among HIV-infected young men who have sex with men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2018;95(4):576–83.

Ompad DC, Kapadia F, Bates FC, Blachman-Forshay J, Halkitis PN. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between arrest and unprotected anal sex among young men who have sex with men: the P18 Cohort Study. J Urban Health. 2015;92(4):717–32.

Fisher DG, Milroy ME, Reynolds GL, Klahn JA, Wood MM. Arrest history among men and sexual orientation. Crime Delinquency. 2004;50(1):32–42.

Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Guillemi S, Hogg R, et al. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(9):1215–21.

Centers for Disease C, Prevention. HIV transmission among male inmates in a state prison system—Georgia, 1992–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(15):421–6.

Nijhawan AE. Infectious diseases and the criminal justice system. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352(4):399–407.

Fogel CI. Hard time: the stressful nature of incarceration for women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1993;14(4):367–77.

Browning SL, Miller RR, Spruance LM. Criminal incarceration dividing the ties that bind: Black men and their families. Impacts of incarceration on the African American family. London: Routledge; 2018. p. 87–102.

Comfort M, Grinstead O, McCartney K, Bourgois P, Knight K. “You can't do nothing in this damn place”: sex and intimacy among couples with an incarcerated male partner. J Sex Res. 2005;42(1):3–12.

Rindfuss RR, Stephen EH. Marital noncohabitation: separation does not make the heart grow fonder. J Marriage Fam. 1990;52:259–70.

May RM, Anderson RM. Transmission dynamics of HIV infection. Nature. 1987;326(6109):137–42.

Bassett E, Moore S. Social capital and depressive symptoms: the association of psychosocial and network dimensions of social capital with depressive symptoms in Montreal, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2013;86:96–102.

Åslund C, Nilsson KW. Social capital in relation to alcohol consumption, smoking, and illicit drug use among adolescents: a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:33.

Kurtz SP. Arrest histories of high-risk gay and bisexual men in Miami: unexpected additional evidence for syndemic theory. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(4):513–21.

Meyer IH, Flores AR, Stemple L, Romero AP, Wilson BD, Herman JL. Incarceration rates and traits of sexual minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):267–73.

Hensley C, Tewksbury R, Castle T. Characteristics of prison sexual assault targets in male Oklahoma correctional facilities. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18(6):595–606.

Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, DiFranceisco W, Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Amirkhanian YA, et al. Correlates of internalized homonegativity among black men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(3):212–26.

Wright EM, Fagan AA, Pinchevsky GM. The effects of exposure to violence and victimization across life domains on adolescent substance use. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(11):899–909.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2005. HIV/AIDS Surveill Rep. 2007;17:1–54.

Kimerling R, Armistead L, Forehand R. Victimization experiences and HIV infection in women: associations with serostatus, psychological symptoms, and health status. J Trauma Stress. 1999;12(1):41–58.

Turner AK, Jones KC, Rudolph A, Rivera AV, Crawford N, Lewis CF. Physical victimization and high-risk sexual partners among illicit drug-using heterosexual men in New York City. J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):957–68.

Hotton A, Quinn K, Schneider J, Voisin D. Exposure to community violence and substance use among Black men who have sex with men: examining the role of psychological distress and criminal justice involvement. AIDS Care. 2019;31(3):370–8.

Gonnerman J. Do jails kill people? The New Yorker 2019 February 20, 2019.

Schnittker J, John A. Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(2):115–30.

Welte JW, Barnes GM. The relationship between alcohol-use and other drug-use among New-York state college-students. Drug Alcohol Depen. 1982;9(3):191–9.

Pratt D, Piper M, Appleby L, Webb R, Shaw J. Suicide in recently released prisoners: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet. 2006;368(9530):119–23.

Gossop M, Manning V, Ridge G. Concurrent use and order of use of cocaine and alcohol: behavioural differences between users of crack cocaine and cocaine powder. Addiction. 2006;101(9):1292–8.

Moore K, Stuewig J, Tangney J. Jail inmates' perceived and anticipated stigma: implications for post-release functioning. Self Identity. 2013;12(5):527–47.

Hensley C. Attitudes toward homosexuality in a male and female prison: an exploratory study. Prison J. 2000;80(4):434–41.

Kupers TA. Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prison. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61(6):713–24.

Sit V, Ricciardelli R. Constructing and performing sexualities in the penitentiaries: attitudes and behaviors among male prisoners. Crim Justice Rev. 2013;38(3):335–53.

Alarid LF. Sexual orientation perspectives of incarcerated bisexual and gay men: the county jail protective custody experience. Prison J. 2000;80(1):80–95.

Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Eshleman SH, Wang L, Mannheimer S, del Rio C, et al. Correlates of HIV acquisition in a cohort of Black men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV prevention trials network (HPTN) 061. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e70413.

Gregory M. Herek BG. AIDS, identity, and community: the HIV epidemic and Lesbians and gay men. 1995 December 20, 2013. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Issues. https://sk.sagepub.com/books/aids-identity-and-community.

Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013.

Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–199.

Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld C, Palmer J, Oser C, Kaplan A, Krietemeyer J, et al. Relationships and HIV risk among incarcerated women. Prison J. 2007;87(1):143–65.

Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, White BL, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and implications for post-release HIV transmission. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):365–75.

Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601.

Khan MR, El-Bassel N, Golin CE, Scheidell JD, Adimora AA, Coatsworth AM, et al. The committed intimate partnerships of incarcerated African-American men: implications for sexual HIV transmission risk and prevention opportunities. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(7):2173–85.

Rogers SM, Khan MR, Tan S, Turner CF, Miller WC, Erbelding E. Incarceration, high-risk sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted infections in an urban population. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(1):63–8.

Browning SL, Miller RR, Spruance LM. Criminal incarceration dividing the ties that bind: black men and their families. J Afr Am Men. 2001;6(1):87–102.

Knittel AK, Snow RC, Riolo RL, Griffith DM, Morenoff J. Modeling the community-level effects of male incarceration on the sexual partnerships of men and women. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2015(147):270–9.

Knittel AK, Snow RC, Griffith DM, Morenoff J. Incarceration and sexual risk: examining the relationship between men's involvement in the criminal justice system and risky sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2703–14.

Marshall T, Simpson S, Stevens A. Use of health services by prison inmates: comparisons with the community. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2001;55(5):364–5.

Schneider JA, Kozloski M, Michaels S, Skaathun B, Voisin D, Lancki N, et al. Criminal justice involvement history is associated with better HIV care continuum metrics among a population-based sample of young black MSM. Aids. 2017;31(1):159–65.

Harawa NT, Brewer R, Buckman V, Ramani S, Khanna A, Fujimoto K, et al. HIV, sexually transmitted infection, and substance use continuum of care interventions among criminal justice-involved black men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S4):e1–e9.

Voisin DR. The relationship between violence exposure and HIV sexual risk behaviors: does gender matter? Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(4):497–506.

Bronson J, Carson EA. Prisoners in 2017. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6546. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2019.

Valera P, Chang Y, Lian Z. HIV risk inside U.S. prisons: a systematic review of risk reduction interventions conducted in U.S. prisons. AIDS Care. 2017;29(8):943–52.

Underhill K, Dumont D, Operario D. HIV prevention for adults with criminal justice involvement: a systematic review of HIV risk-reduction interventions in incarceration and community settings. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e27–e53.

Lima VD, Graf I, Beckwith CG, Springer S, Altice FL, Coombs D, et al. The impact of implementing a test, treat and retain HIV prevention strategy in Atlanta among black men who have sex with men with a history of incarceration: a mathematical model. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0123482.

Schrimshaw EW, Downing MJ Jr, Siegel K. Sexual venue selection and strategies for concealment of same-sex behavior among non-disclosing men who have sex with men and women. J Homosex. 2013;60(1):120–45.

Grov C, Crow T. Attitudes about and HIV risk related to the "most common place" MSM meet their sex partners: comparing men from bathhouses, bars/clubs, and Craigslist.org. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(2):102–16.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the following groups who made possible the HPTN 061 study: HPTN 061 study participants; HPTN 061 Protocol co-chairs, Beryl Koblin, PhD, Kenneth Mayer, MD, and Darrell Wheeler, PhD, MPH; HPTN061 Protocol team members; HPTN Black Caucus; HPTN Network Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Statistical and Data Management Center, Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research and Prevention; HPTN CORE Operating Center, Family Health International (FHI) 360; Black Gay Research Group; clinical research sites, staff, and Community Advisory Boards at Emory University, Fenway Institute, GWU School of Public Health and Health Services, Harlem Prevention Center, New York Blood Center, San Francisco Department of Public Health, the University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Behavioral and Addiction Medicine, and Cornelius Baker, FHI 360. We are thankful to Sam Griffith, Senior Clinical Research Manager, FHI 360, and Lynda Emel, Associate Director, HPTN Statistical and Data Management Center, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, for their considerable assistance with HPTN 061 data acquisition and documentation.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant ‘Stop-and-Frisk, Arrest, and Incarceration and STI/HIV Risk in Minority MSM’ (Principal Investigator: Maria Khan; R01 DA044037). This research uses data from the HIV Prevention Trials Network 061 (HPTN 061) study. HPTN 061 grant support was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): Cooperative Agreements UM1 AI068619, UM1 AI068617, and UM1 AI068613. Additional site funding included Fenway Institute Clinical Research Site (CRS): Harvard University CFAR (P30 AI060354) and CTU for HIV Prevention and Microbicide Research (UM1 AI069480); George Washington University CRS: District of Columbia Developmental CFAR (P30 AI087714); Harlem Prevention Center CRS and NY Blood Center/Union Square CRS: Columbia University CTU (5U01 AI069466) and ARRA funding (3U01 AI069466-03S1); Hope Clinic of the Emory Vaccine Center CRS and The Ponce de Leon Center CRS: Emory University HIV/AIDS CTU (5U01 AI069418), CFAR (P30 AI050409) and CTSA (UL1 RR025008); San Francisco Vaccine and Prevention CRS: ARRA funding (3U01 AI069496-03S1, 3U01 AI069496-03S2); UCLA Vine Street CRS: UCLA Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases CTU (U01 AI069424). The funder had a role in the design of the study by providing input into the design. The funder did not have a role in the data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The funding agencies had no role in designing the research, data analyses and preparation of the report. Maria Khan, Charles Cleland, and Joy Scheidell received support from the New York University Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (P30 DA011041). Maria Khan additionally was supported by the New York University-City University of New York (NYU-CUNY) Prevention Research Center (U48 DP005008). Typhanye Dyer and Rodman Turpin were supported by the University of Maryland Prevention Research Center (U48 DP006382). Russell Brewer was supported by a grant from NIDA (P30 DA027828-08S1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflicts were declared.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Severe, M., Scheidell, J.D., Dyer, T.V. et al. Lifetime Burden of Incarceration and Violence, Internalized Homophobia, and HIV/STI Risk Among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in the HPTN 061 Study. AIDS Behav 25, 1507–1517 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02989-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02989-w