Abstract

Among 958 applicants to a supportive housing program for low-income persons living with HIV (PLWH) and mental illness or a substance use disorder, we assessed impacts of housing placement on housing stability, HIV care engagement, and viral suppression. Surveillance and administrative datasets provided medical and residence information, including stable (e.g., rental assistance, supportive housing) and unstable (e.g., emergency shelter) government-subsidized housing. Sequence analysis identified a “quick stable housing” pattern for 67% of persons placed by this program within 2 years, vs. 28% of unplaced. Compared with unplaced persons not achieving stable housing quickly, persons quickly achieving stable housing were more likely to engage in care, whether placed (per Poisson regression, ARR: 1.14;95% CI 1.09–1.20) or unplaced (1.19;1.13–1.25) by this program, and to be virally suppressed, whether placed (1.22;1.03–1.44) or unplaced (1.26, 1.03–1.56) by this program. Housing programs can help homeless PLWH secure stable housing quickly, manage their infection, and prevent transmission.

Resumen

Unas 958 personas de bajos recursos y quienes viven con VIH y enfermedades mentales o bien presentan problemas de abuso de sustancias solicitaron a un programa de vivienda complementada con servicios de apoyo. Entre ellas, se evaluó los impactos de la colocación en viviendas sobre la estabilidad en la misma, así como la participación en los cuidados médicos para el VIH, y la supresión de la carga viral. Las bases de datos administrativas y del registro de vigilancia brindaron información médica y domiciliar, incluyendo información sobre vivienda estable (por ejemplo, asistencia de pago de renta a largo plazo, o vivienda complementada con servicios de apoyo) y vivienda inestable (por ejemplo, alojamiento de emergencia temporal) subsidiada por el gobierno. El método “análisis de secuencia” permitió identificar una pauta caracterizada por estabilidad domiciliar conseguida de modo ligero (es decir, de forma oportuna) en el 67% de las personas quienes fueron colocadas por este programa dentro de un lapso de dos años, comparado con 28% de las personas quienes no fueron colocadas. En comparación con las personas quienes no fueron colocadas y no lograron estabilidad de vivienda de modo ligero, las personas quienes lograron estabilidad de vivienda de modo ligero tuvieron una mayor probabilidad de participar en cuidados médicos, ya sea que fueran colocadas (según regresión de Poisson, cociente de riesgo ajustado: 1.14; intervalo de confianza de 95%: 1.09-1.20) o no fueran colocadas (1.19, 1.13-1.25) por este programa, así como de lograr la supresión de la carga viral, ya sea que fueran colocadas (1.22, 1.03-1.44) o no fueran colocadas (1.26, 1.03-1.56) por este programa. Los programas que facilitan la colocación en o el pago de vivienda y apoyo en el mismo pueden ayudar a las personas con VIH y sin hogar obtener vivienda estable de modo ligero, controlar su infección, y prevenir la transmisión.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

In the United States, HIV disproportionately affects low-income persons [1, 2]. There are millions more very-low-income Americans than there are affordable and available homes, and this gap is especially acute in New York City (NYC) [3], which has record high numbers of homeless persons [4]. Compared with stably housed persons living with HIV (PLWH), homeless PLWH are more likely to suffer from mental illness, substance use disorders, and other comorbidities that may act as barriers to effective services [5]. Homeless PLWH are less likely than stably housed PLWH to receive routine medical care and adhere to HIV treatment and more likely to have detectable viral loads (VL), increasing their likelihood of poor health outcomes and onward transmission of HIV [5].

This link between unstable housing, low engagement in HIV care, and decreased rates of viral suppression for PLWH is supported by a breadth of observational and experimental research, including multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs). The RCTs support a causal relationship, among homeless and unstably housed PLWH, between acquiring stable housing and achieving viral suppression. Wolitski et al. [6] randomly assigned participants in three cities across the United States to receive either immediate rental assistance (treatment) or standard housing assistance (control). While the intent to treat analysis was complicated by a high proportion of the control group obtaining stable housing through other programs, the as-treated analysis found that participants experiencing homelessness were 2.5 times as likely to have a detectable viral load as those who did not experience homelessness. Buchanan et al. [7] randomized homeless individuals from inpatient hospitals in Chicago to receive either supportive housing (treatment) or usual discharge planning and care (control). The intervention group was statistically significantly more likely to have lower median viral loads after 12 months. Towe et al. [8] randomly assigned residents of NYC HIV emergency housing to receive assistance for rapid permanent rehousing and case management for 1 year (treatment) or standard housing placement assistance (control). Over the next year, relative to the control group, the intervention group experienced almost twice the housing placement rates and twice the improvement in viral suppression.

In addition to RCTs, both longitudinal [9,10,11,12] and cross-sectional [13,14,15] observational studies have shown a consistent association between unstable housing and poor care and/or suppression outcomes for PLWH. While the outcomes in these studies are often clearly defined (viral suppression at last VL test, care visit within study period), the exposure of “housing” is less distinct. Much of the literature on HIV and housing fails to account for the wide array of potential living situations between homelessness and stable housing, or for the time-varying nature of housing as a variable (i.e., moving in and out of different housing situations). As a recent example, Galarraga et al. used an instrumental variables approach to find that unstable housing had a negative effect on viral suppression and adequate CD4 cell count in a long-running cohort of PLWH at multiple sites in the US (including NYC) [16]. Housing status was dichotomized into stable/unstable categories and based on self-report of current living situation—participants were not asked about history of housing or homelessness.

The limitations of focusing on literal homelessness at one point in time, rather than a more nuanced and dynamic understanding of living situation as a changing part of an individual’s experience over time, have been noted elsewhere [5]. In response, some researchers have begun to explore housing patterns or trajectories and their relation to care and suppression among PLWH. Marcus et al. used a multisite cohort to dynamically investigate patterns of housing stability, with housing status (improved consistently versus not) as the outcome of interest, finding that participants with recent injection drug use had less consistent housing improvement [17]. Despite this relatively novel approach, the authors acknowledged limitations in their classification of housing, which was determined in part by federal standards. There remains little to no research that characterizes housing status as a dynamic, nuanced exposure of interest and its relation to care and viral suppression among PLWH; previous research in this area has focused only on time housed in a homeless shelter or jail [18].

The New York City/New York State–Initiated Third Supportive Housing Program (NY/NY III), instituted in 2007, is a joint effort between NYC and New York State (NYS) that provides government-subsidized supportive housing for populations chronically or at risk of homelessness [19]. As is typical for supportive housing programs, this includes help finding and paying for an apartment (sometimes in a congregate facility, but mostly scattered-site), and connection with a case manager for ongoing housing and non-housing support services. One of the included populations is multiply diagnosed PLWH, i.e., PLWH with co-morbidities of mental illness or substance use disorder. NY/NY III takes a Housing First approach to placing applicants living with HIV, i.e., immediate permanent supportive housing placement for unstably housed persons, without requiring sobriety or treatment [20].

Previous research has explored the relationship between supportive housing provided by NY/NY III and new HIV diagnoses, and between NY/NY III and AIDS-free survival among PLWH [21, 22]. However, little is known about the effects of NY/NY III or other government-subsidized housing programs on housing stability patterns over time and the medical outcomes of HIV care and viral suppression among New Yorkers with HIV. Given the challenges to HIV treatment adherence among PLWH with housing and behavioral health issues, it is important to understand whether and how housing programs improve HIV viral suppression via increased housing stability over time. In this evaluation, we characterized housing stability patterns over time and described how housing stability influences HIV care engagement and viral suppression, prior to and after enrollment by PLWH in the NY/NY III program, overall and by housing placement.

Methods

Population, Data Sources, and Housing Types

This evaluation used matched governmental administrative data from NYC and NYS, which included dates of residence in jails, hospitals, government-subsidized housing for low-income persons with chronic physical or mental health conditions, and homeless shelters. Detailed information about the data sources and matching for evaluation of the NY/NY III supportive housing program has been published previously [23, 24]. Briefly, data were provided by units now within the NYC Department of Social Services, as well as the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, NYC Department of Correction, and NYS Office of Mental Health. Independent human review of sample cases indicated acceptable matching performance (sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 96%). Deterministic matching using first and last name, date of birth, and Social Security number was used to link service data with NY/NY III data. Probabilistic matching with first, middle, and last name, date of birth, Social Security number, sex assigned at birth, and address (when available) was conducted with other datasets using QualityStage software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) [25].

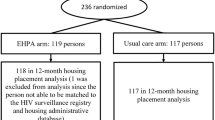

The evaluation population consisted of adults living with HIV who presented themselves to a housing services provider and applied for and were determined to be eligible for NY/NY III between 2007 and 2010. Applicants were considered eligible for NY/NY III if they (1) were chronically homeless (i.e., either staying at least two of the last 4 years in a homeless shelter or living on the street, or being disabled and spending at least one of the last 2 years in a shelter or living on the street) and (2) had been diagnosed with a serious and persistent mental illness, a substance use disorder, or both mental illness and chemical addiction, or (3) were young adults aging out of foster care and thus at risk of homelessness. This evaluation was limited to the subset of these eligible applicants who had diagnosed HIV infection as of their eligibility date, determined by matching the data to the NYC HIV surveillance registry.

More eligible people enroll in the NY/NY III program than can be placed in NY/NY III housing. There are no additional criteria for housing placement, and while placement is not random, housing agencies must place someone after interviewing no more than three eligible applicants for a vacant unit. We categorized eligible applicants living with HIV into two groups: (1) applicants who were placed in NY/NY III housing for > 7 consecutive days (“placed”) and (2) applicants who were not placed in NY/NY III housing during 2 years after eligibility or were placed in NY/NY III housing for ≤ 7 consecutive days (“unplaced”). Seventy-five placed persons living with HIV were excluded because they were living in non-NY/NY III government-subsidized housing within one day prior to NY/NY III housing placement and therefore considered to be pre-exposed to government-subsidized housing. To reduce bias, the date of a person’s first enrollment in the NY/NY III housing program, rather than housing placement, was the baseline time point for this evaluation: time from enrollment/eligibility to placement varied, and some persons were not placed at all. For each person, we examined the 12-month period pre-enrollment and 24-month period post-enrollment.

The NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Institutional Review Board determined that this is a non-research evaluation activity.

Outcomes and Covariates

A primary outcome of interest was patterns of housing stability, particularly as they related to stable housing, in the 2 years (24 months) following enrollment. Housing type was classified for the analysis as one of the following five types: stable government-subsidized housing (e.g., NY/NY III, public housing, or rental subsidies with or without supportive housing [supportive housing being housing plus services for persons facing homelessness who are also living with mental illness or substance use disorder] through the large NYC HIV/AIDS Services Administration [HASA] program or federally funded Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS [HOPWA] and Ryan White programs), unstable government-subsidized housing (e.g., HASA emergency housing including supported or transitional single room occupancy, or NYC homeless shelters), jail/incarceration, medical or psychiatric institutionalization/hospitalization (e.g., as indicated by Medicaid claims or the NYS Office of Mental Health psychiatric hospitalization registry), or—during unaccounted time outside of these administrative datasets—non-institutional. While participants using rental subsidies did not reside directly in government-owned or operated housing, this living situation has been considered stable in multiple noteworthy studies on housing and health [6, 26]. We conceptualized a stable housing pattern as continuous placement in stable government-subsidized housing, rarely interrupted by stays in other housing types; it considered both housing type and duration.

Other primary outcomes included engagement in HIV-related medical care (also referred to as “care engagement”), as indicated by having at least one reported CD4 count, CD4 percent, or VL test in the second year (months 13–24) following enrollment; and HIV viral suppression, as indicated by having at least one VL test in the second year following enrollment and having the result of the last test in that period be ≤ 400 copies/mL. Matched HIV registry data provided information on these outcomes, as it contained for all diagnosed and reported NYC PLWH the dates of HIV diagnoses and dates and values of all subsequent HIV-related laboratory tests, including VLs and CD4 counts and percents. We focused on medical outcomes in the second year after enrollment to allow time for housing patterns to be established and potentially influence subsequent care outcomes, but to better understand the outcomes over time, we also measured them in the first year (months 1–12) following enrollment.

One exposure was placement in NY/NY III supportive housing for > 7 days, which typically occurred ~ 50 days after a person was determined to be eligible. For the multivariable analyses of HIV medical outcomes, we classified the exposure both in terms of placement in NY/NY III housing (vs. non-placement) and housing stability patterns that emerged in sequence analysis (which we ultimately dichotomized as quick stable housing vs. patterns of delayed stable housing or non-institutional housing).

Covariates from the NY/NY III application document included the following characteristics: age at enrollment, gender identity, race and ethnicity, education, substance use in the past 6 months, diagnosed mental illness, and activities of daily living requiring assistance. Gender identity values were woman and man. Race/ethnicity values were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, Asian, and all other non-Hispanic racial identities. Education was self-reported. Substance use in the past 6 months was based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnoses of alcohol- or other substance-related disorder recorded and/or confirmed by clinicians at social services agencies. Diagnosed mental illness, which excluded mental retardation and substance use disorders, was based on clinician-recorded Axis I or Axis II codes and according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Activities of daily living included walking, climbing, traveling, hearing, vision, feeding oneself, meal preparation, housekeeping, cognitive functions, managing finances, toileting, and personal hygiene.

Covariates also included the following clinical characteristics based on data in the HIV registry: CD4 count, care engagement, and VL, each in the 12 months prior to enrollment; HIV/AIDS diagnosis year; and estimated ART eligibility based on CD4 count and DHHS ART guidelines as of NY/NY III enrollment. Finally, pre-baseline housing stability pattern was a covariate, as was calendar year of placement, given changes in ART guidelines and potentially in the HIV housing landscape.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a sequence analysis to identify clusters of housing patterns for 1 year pre- and 2 years post-enrollment (Fig. 1a, b; see Appendix for details) [27, 28]. We calculated the distribution of the analysis population by pre-enrollment demographic and clinical characteristics, overall and by NY/NY III housing placement (placed vs. unplaced), and used a Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test of association or median two-sample test to compare placed and unplaced. We calculated the distribution of post-enrollment housing patterns overall and by NY/NY III housing placement, and the distribution of post-enrollment medical outcomes overall and by placement and housing patterns.

a Housing patterns among persons living with HIV in the 12 months prior to enrollment in the NY/NY III supportive housing program. b Housing patterns among persons living with HIV in the 24 months following enrollment in the NY/NY III supportive housing program. Notes: Each graph represents a cluster of housing patterns that emerged in sequence analysis. After the sequence analysis was conducted, each resulting cluster was given a name by the investigators to succinctly characterize it, based on assessment of the housing types and their predominant order and length of time. Each horizontal line in the graphs represents one person’s sequence of housing types for each month. The x-axis represents time in months during the 1 year (12 months) prior to enrollment in the NY/NY III supportive housing program (a) or during the 2 years (24 months) following enrollment (b). A change in color in a horizontal line reflects that a person’s predominant housing type changed. For example, a blue line for the first 2 months after enrollment that then becomes a yellow line afterwards represents a person living in unstable government-subsidized housing for two months and then moving to stable government-subsidized housing; such a housing pattern is typical in the post-enrollment cluster that investigators named “quick stable housing”

Finally, we conducted multivariable log-linear Poisson regressions to test whether having the outcome of a stable housing pattern was associated with the exposure of NY/NY III housing placement, and whether the outcomes of being in care and being virally suppressed were associated with the exposures of placement and a stable housing pattern, controlling for pre-enrollment housing patterns and demographic and clinical characteristics. Although analyses of binary outcomes do not often use Poisson regression, it is appropriate when modified with a robust error variance [29], as we have done. Models of suppression were built for the entire analytic population as well as the subset of persons engaged in care in that year. Regression models were adjusted for gender identity (man, woman), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, ≥ 55 years), race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, white, all others), substance use in the past 6 months, and pre-enrollment care status (for analysis of medical care) or suppression status (for analysis of suppression).

We determined statistical significance using two-sided p-value < 0.05. Sequence analysis was performed using TraMineR and cluster packages in R 3.3.1 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All other analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Baseline Demographic, Clinical, and Housing Characteristics

During 2007–2010, 958 PLWH applied to and were eligible for (i.e., enrolled in) NY/NY III. Of these, 72% were male, 91% were Black or Hispanic, 86% had a diagnosed alcohol- or substance-related disorder in the past 6 months, and 99% had a diagnosed mental illness; median age at enrollment was 47 years (Table 1). Young adults aging out of foster care were a small minority of our final population (11 persons), of whom only 2 did not have mental illness or substance use disorder. Therefore, 99% of PLWH in our analysis were chronically homeless and living with a mental illness. The following pre-enrollment housing patterns were identified: unstable government-subsidized housing (72%), non-institutional (16%), and multiple housing types (12%) (Fig. 1a; clusters validation ratio = 0.285). In the 12 months leading up to enrollment, 94% of persons were engaged in care, 65% had a CD4 count of at least 200 cells/mm3 (per last pre-enrollment CD4 count), and 34% were virally suppressed (per last pre-enrollment VL).

Housing Placement Overall and by Baseline Characteristics

Four hundred seventy-three persons (49%) were placed in NY/NY III housing (Table 1). They were similar to the 485 (51%) unplaced persons on most baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and pre-enrollment housing patterns. However, placed and unplaced persons differed by some baseline characteristics. For example, placed persons were more likely to have been, before enrollment, living in unstable government-subsidized housing (77% vs. 68%; p = 0.01 for overall difference in housing types), engaged in care (96% vs. 92%; p = 0.03), and estimated to be eligible for ART (69% vs. 59%; p < 0.01), and less likely to have used substances in the last six months (84% vs. 89%; p = 0.02). While 7 days in NY/NY III housing was the lower bound for inclusion in the placement group, median days in NY/NY III housing in the 24 months after enrollment among the 473-person placed group was actually 579 days (interquartile range: 292–683).

Housing Stability After Enrollment

The following post-enrollment housing patterns were identified: stable government-subsidized housing within a half-year (“quick stable housing,” 47%), stable government-subsidized housing after 1 year (“delayed stable housing,” 30%), and non-institutional (23%) (Fig. 1b; clusters validation ratio = 0.444). Persons placed and unplaced in NY/NY III housing had different housing patterns post-enrollment (p < 0.01; Fig. 2), with placed persons more likely than unplaced to be quickly stably housed (67% vs. 28%) and less likely to be non-institutionalized (11% vs. 34%). This difference persisted after adjustment for baseline characteristics, with placed persons more than two times as likely as unplaced to have quick stable housing after enrollment (vs. not having quick stable housing [delayed stable housing or non-institutional], adjusted relative risk [ARR] = 2.36, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.02–2.75).

HIV-Related Medical Care and Viral Suppression After Enrollment

In this population of PLWH, nearly all of whom were living with mental illness or substance use disorder, 90% were engaged in care and 44% virally suppressed in the second year following enrollment in the NY/NY III supportive housing program. Persons placed in NY/NY III housing were more likely than unplaced to be engaged in care (93% vs. 87%, p < 0.01) and virally suppressed (47% vs. 41%, p = 0.10) in the second year post-enrollment, although the difference in percentage virally suppressed was not statistically significant. These differences were driven by the difference between placed and unplaced in the proportion achieving quick stable housing, since persons who were quickly stably housed had the highest rates of care engagement (> 95% at year 2) and viral suppression (50% at year 2; Fig. 3; placed persons with non-institutional housing patterns had higher suppression rates at 12 months).

HIV medical care engagement and viral suppression at, and for 2 years after, the enrollment of persons living with HIV in the NY/NY III supportive housing program, by placement in NY/NY III housing and housing stability patterns. Notes: HIV medical care engagement and viral suppression are calculated based on 12 months of data. Outcomes at 0 months since program enrollment are baseline measures based on the 12 months prior to enrollment. Outcomes at 12 months are based on the first year following enrollment, and those at 24 months are based on the second year following enrollment

In multivariable log-linear Poisson regressions of care engagement and viral suppression in the second year post-enrollment, the reference group was unplaced persons not quickly achieving stable housing (i.e., persons not placed in NY/NY III housing who had either of two housing patterns: delayed stable housing or non-institutional). Compared to that population, persons quickly achieving stable housing were more likely to be engaged in care, whether they were placed (ARR = 1.14, 95% CI 1.09–1.20) or unplaced (ARR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.13–1.25) in NY/NY III housing (Table 2). Persons quickly achieving stable housing were also more likely to be virally suppressed, whether placed (ARR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.03–1.44) or unplaced (ARR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.03–1.56). However, among the subset of persons engaged in care, suppression was not associated with NY/NY III housing placement and pattern (e.g., placed quick stable housing, ARR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.76–1.18).

Discussion

As might be expected, placement in government-subsidized supportive housing was associated with a quick stable housing pattern for low-income persons with HIV who had a range of pre-enrollment housing types, and almost all of whom had diagnosed mental illness and/or substance use disorder. Notably, in the second year after enrollment in the program, 90% of persons in our analysis were engaged in HIV-related medical care, but fewer than half were virally suppressed, suggesting that many were not prescribed or adhering to ART even though they visited a doctor. Persons achieving quick stable housing, whether placed or unplaced by this particular housing program, went on to have better HIV outcomes in the second year than persons with other housing patterns: they were 14–19% more likely to engage in care and 22–26% more likely to achieve viral suppression.

Most persons in the analysis, whether placed or unplaced by NY/NY III, had a pattern of stable government-subsidized housing within 2 years (i.e., the quick or delayed stable housing patterns), with placed persons more than twice as likely as unplaced to be stably housed quickly. This is probably due to the NY/NY III program itself, since prior to enrollment, placed persons were similar to unplaced on most characteristics and actually more likely to have had a pattern of unstable government-subsidized housing. Because NYC has numerous housing programs for low-income persons, it is unsurprising that some persons unplaced by NY/NY III achieved stable government-subsidized housing through other means. Programs explicitly for persons with HIV provide emergency housing, supportive housing, housing subsidies, or housing placement assistance to over 30,000 persons per year; NY/NY III’s program for PLWH is a relatively small program among these, and not the only one with case management [30]. (Also, unpublished data, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2017) Our analysis suggests that NY/NY III together with other NYC housing programs available to PLWH may be meeting housing needs for many but not all unstably housed PLWH. (A minority of PLWH are accessing emergency housing, such as NYC homeless shelters or HASA’s single room occupancy units [30, 31].) In other settings with fewer subsidized housing options, a particular housing program may have a relative impact on stable housing among PLWH that is greater than we observed. Our analysis underscores that, when analyzing the effects of housing programs, it is important to distinguish between enrollment, achievement of housing outcomes such as housing placement by the program, and achievement of stable housing from any source.

Our findings are consistent with literature on the effects of better housing on care and viral suppression among persons with HIV. A literature review by Aidala et al. found that PLWH generally are more likely to be engaged in care and virally suppressed if they are stably housed than if homeless or unstably housed [5]. Three randomized controlled trials in US cities found that homeless or unstably housed PLWH who were offered permanent housing were more likely than those receiving usual services to achieve viral suppression [6,7,8]. In NYC, PLWH without recent housing need were more likely to be engaged in care and treatment than those with housing need [32], PLWH enrolled in housing services were more likely to be virally suppressed if they had not needed emergency housing [33], and PLWH who were initially homeless and later housed were more likely to achieve viral suppression than PLWH with sporadic incarceration and homelessness and PLWH with extensive incarceration [18]. Our analysis extends these findings by dynamically assessing housing status in a real-world program setting and using large administrative matches to measure exposures and outcomes.

We found that relatively quick movement from homelessness to government-subsidized housing was associated with viral suppression, which suggests that housing helps to decrease HIV transmissibility. While many health-related analyses about the effects of housing focus on outcomes related to addiction and mental illness, our analysis joins a few others in suggesting a link between stable housing and reduced transmission potential of an infectious disease, including the aforementioned RCTs of housing interventions for homeless or unstably housed PLWH [5,6,7,8]. As additional examples, an analysis of youth placed in the NY/NY III supportive housing program found that placement was associated with greater housing stability and lower rates of sexually transmitted infections [23]. A prospective analysis of injection drug users in a Canadian city found that those unstably housed were more likely to acquire hepatitis C [34]. Housing may thus benefit the health of not only the individual served but also their intimate contacts.

Our findings suggest that the Housing First approach to housing placement may improve health and reduce the risk of HIV transmission, even or especially for persons with chronic physical, mental, or behavioral health issues. This is consistent with previous literature on the Housing First approach which has shown improved housing and/or health outcomes for persons with substance use disorders and mental illness [35,36,37,38,39]. For example, among chronically homeless adults living with mental illness, those randomized to immediate housing placement had better housing outcomes and no worse symptoms of mental illness or substance misuse than those randomized to housing contingent on treatment and sobriety [35]. And among chronically homeless adults with high alcohol-related emergency health care use, health care and public service costs declined after being randomly selected for immediate Housing First placement, and this decline was greater among placed persons than controls, who had been wait-listed for placement [39].

Limitations

Our analysis is subject to several limitations. Placement in NY/NY III housing was not randomized, so placed persons may have differed systematically from unplaced persons in ways that affected quick stable housing. We attempted to address this by controlling in the housing analysis for factors hypothesized to be associated with both placement and housing [40], but there may have been unmeasured confounders.

Supportive housing is not homogeneous. Despite access to multiple administrative data sources, we did not have information on the type of supportive housing (e.g., scattered-site versus single site) or the intensity and frequency of case management and other supportive services accessed by individual participants during the study period. However, we do have some aggregate information about post-placement case management for NY/NY III tenants as a whole. Within a given 2-week period, 90% received case management services, averaging (overall as well as for PLWH) just over 2 h [41]. The case management services provided to the most NY/NY III tenants and that occupied the most time were related to housing/independent living (e.g., money management, entitlement assistance, and conflict resolution) and mental health (e.g., counseling, support groups, and medication management). Approximately three-quarters of NY/NY III tenants who said they needed help with managing medications, getting other social services, or seeing a doctor said they received each of those types of help. A multisite RCT with homeless adults living with mental illness in Canadian cities found that both intensity and frequency of case management may play a role in determining the degree and nature of housing, health, and quality of life outcomes, while also emphasizing the effectiveness of a Housing First model compared to treatment as usual, regardless of supportive housing type or service intensity [42, 43].

Persons classified as having non-institutional residence were considered to be unstably housed, although their housing situation was unknown and some could have been stably housed independently or receiving housing or medical services from providers not included in the match, such as outside of NY. Such potential misclassifications are expected to be few in number because we included numerous data sources, services are concentrated in NYC, and it may be difficult for persons from this high-need population to achieve housing stability independently. Nevertheless, such misclassifications could have resulted in an inflated association between NY/NY III placement and quick stable housing, and between quick stable housing and care and suppression.

We used electronically reported HIV-related laboratory tests as a proxy for care engagement, but some of these tests may have been from inpatient or emergency visits among persons not in routine outpatient HIV care. This seems especially possible given that a much higher proportion appeared engaged in care than virally suppressed. This limitation may affect persons with hospitalizations the most, overestimating the proportion engaged in care. Persons in the analysis averaged 3 hospitalizations in the 24-month post-placement period, and persons with quick stable housing had fewer hospitalizations than persons with delayed stable housing. This means that quick stable housing may be even more strongly associated with engagement in routine outpatient HIV care than we found.

We could not ensure that ascertainment and definitions of some covariates were consistent across sites. However, our main exposures (program placement and housing stability patterns) and outcomes (care and suppression) did not rely on program intake forms and were consistently reported and defined.

Strengths

This analysis longitudinally ascertained housing status using multiple matched administrative databases. These delivered information about housing programs as well as other institutions providing housing such as jails, hospitals, and behavioral treatment facilities. If unplaced by NY/NY III, NYC PLWH may pursue housing placement via other programs including HASA, HOPWA, and Ryan White; these were all included in the match, and our exposure categories in the analyses of care and suppression accounted for the fact that persons unplaced by NY/NY III had access to these. We assessed housing status dynamically over a period of time, rather than only dichotomously or at a single time point, as few prior analyses have done [23].

HIV status and medical outcomes were ascertained via the HIV registry, which has high reporting rates. Specifically, approximately 93% of persons with HIV in NYC have been diagnosed and reported to the registry [44], and HIV-related laboratory tests are electronically reported and estimated to be > 97% complete, with minimal differences in completeness by subgroup (unpublished data, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene).

Conclusions

PLWH chronically or at risk of homelessness who were placed in NY/NY III supportive housing were more likely than those unplaced to have quick stable housing. Quick stable housing was associated with higher rates of care engagement and viral suppression, regardless of whether that housing was achieved via placement through this particular supportive housing program or through another government-subsidized housing program. These effects were found for a population made vulnerable not only by their HIV status and unstable housing but also mental illness and substance use disorder. Many unstably housed persons cycle through shelters and jails [45]. Living with HIV, mental illness, most with substance use disorder, and all without a home, the NY/NY III PLWH population may be particularly susceptible to experiencing short-term unstable housing stays prior to their enrollment. Our analysis seems to show that NY/NY III permanent supportive housing, or any quick placement into government-subsidized housing, does reasonably well at stabilizing housing for this population. Expansion of opportunities for PLWH to be housed quickly and affordably may be beneficial for individual and population health. This includes PLWH-specific government housing subsidies, affordable housing options generally, and interventions that offer immediate housing placement, such as Housing First, or other housing options such as those funded by federal HOPWA and Ryan White programs. Finally, given that 90% of these supportive housing applicants were engaged in care in the second year after enrollment but fewer than half were virally suppressed, additional medication prescribing and adherence support may be beneficial for this population.

References

Denning PH, DiNenno EA, Wiegand RE. Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence—24 cities, United States, 2006–2007. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(31):1045–9.

Gillies P, Tolley K, Wolstenholme J. Is AIDS a disease of poverty? AIDS Care. 1996;8(3):351–64.

Joint Center of Housing Studies of Harvard University. The state of the nation's housing, 2016. Cambridge: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University; 2016.

New York City Department of Homeless Services. Daily report. 2016; https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/dhs/downloads/pdf/dailyreport.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2017.

Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, et al. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):e1–e23.

Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):493–503.

Buchanan D, Kee R, Sadowski LS, Garcia D. The health impact of supportive housing for HIV-positive homeless patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 3):S675–680.

Towe VL, Wiewel EW, Zhong Y, Linnemayr S, Johnson R, Rojas J. A randomized controlled trial of a rapid re-housing intervention for homeless persons living with HIV/AIDS: impact on housing and hiv medical outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(9):2315–25.

Muthulingam D, Chin J, Hsu L, Scheer S, Schwarcz S. Disparities in engagement in care and viral suppression among persons with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(1):112–9.

Weiser SD, Yuan C, Guzman D, et al. Food insecurity and HIV clinical outcomes in a longitudinal study of urban homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2013;27(18):2953–8.

Williams CT, Kim S, Meyer J, et al. Gender differences in baseline health, needs at release, and predictors of care engagement among HIV-positive clients leaving jail. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S195–202.

Milloy MJ, Marshall BD, Montaner J, Wood E. Housing status and the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9(4):364–74.

King WD, Larkins S, Hucks-Ortiz C, et al. Factors associated with HIV viral load in a respondent driven sample in Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(1):145–53.

Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV. Health status, health care use, medication use, and medication adherence among homeless and housed people living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2238–45.

Bowen EA, Canfield J, Moore S, Hines M, Hartke B, Rademacher C. Predictors of CD4 health and viral suppression outcomes for formerly homeless people living with HIV/AIDS in scattered site supportive housing. AIDS Care. 2017;29(11):1458–62.

Galarraga O, Rana A, Rahman M, et al. The effect of unstable housing on HIV treatment biomarkers: an instrumental variables approach. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2018;214:70–82.

Marcus R, Groot AD, Bachman S, et al. Longitudinal determinants of housing stability among people living with HIV/AIDS experiencing homelessness. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S7):S552–S56060.

Lim S, Nash D, Hollod L, Harris TG, Lennon MC, Thorpe LE. Influence of jail incarceration and homelessness patterns on engagement in HIV care and HIV viral suppression among New York City adults living with HIV/AIDS. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0141912.

Levanon Seligson A, Lim S, Singh T. New York/New York III supportive housing evaluation: interim utilization and cost analysis. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2013.

U.S. Housing and Urban Development. Housing First in permanent supportive housing. 2014.

Lee CT, Winquist A, Wiewel EW, et al. Long-term supportive housing is associated with decreased risk for new HIV diagnoses among a large cohort of homeless persons in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3083–90.

Hall G, Singh T, Lim SW. Supportive housing promotes AIDS-free survival for chronically homeless HIV positive persons with behavioral health conditions. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:776–83.

Lim S, Singh TP, Gwynn RC. Impact of a supportive housing program on housing stability and sexually transmitted infections among New York City young adults aging out of foster care. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:297–304.

Lim S, Gao Q, Stazesky E, Singh TP, Harris TG, Levanon SA. Impact of a New York City supportive housing program on Medicaid expenditure patterns among people with serious mental illness and chronic homelessness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):15.

IBM InfoSphere QualityStage [computer program]. Armonk, NY;2011.

Arcaya MC, Graif C, Waters MC, Subramanian SV. Health Selection into neighborhoods among families in the moving to opportunity program. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(2):130–7.

Levenshtein VI. Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions, and reversals. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR. 1965;163(4):845–8.

Ward JH Jr. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc. 1963;58:236–44.

Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–6.

HIV/AIDS Services Administration. HASA facts, August 2017. New York: New York City Human Resources Administration; 2017.

Kerker BD, Bainbridge J, Kennedy J, et al. A population-based assessment of the health of homeless families in New York City, 2001–2003. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(3):546–53.

Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, Messeri P, Siegler A. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):101–15.

Beattie CM, Wiewel EW, Zhong Y, et al. Multilevel factors associated with a lack of viral suppression among persons living with HIV in a federally funded housing program. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):784–91.

Kim C, Kerr T, Li K, et al. Unstable housing and hepatitis C incidence among injection drug users in a Canadian setting. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):270.

Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(4):651–6.

Padgett DK, Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Stefancic A. Substance use outcomes among homeless clients with serious mental illness: comparing housing first with treatment first programs. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(2):227–32.

Kertesz SG, Crouch K, Milby JB, Cusimano RE, Schumacher JE. Housing first for homeless persons with active addiction: are we overreaching? Milbank Q. 2009;87(2):495–534.

Palepu A, Patterson M, Moniruzzaman A, Frankish CJ, Somers J. Housing first improves residential stability in homeless adults with concurrent substance dependence and mental disorders. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):e30–36.

Larimer ME, Malone D, Garner MD, et al. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301(13):1349–57.

Lim S, Singh TP, Hall G, Walters S, Gould LH. Impact of a New York City supportive housing program on housing stability and preventable health care among homeless families. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:3437–54.

LevanonSeligson A, Johns M, Lim S, Singh T. Interim report on the New York/New York III supportive housing evaluation. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2010.

Somers JM, Moniruzzaman A, Patterson M, et al. A randomized trial examining housing first in congregate and scattered site formats. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0168745–e01687450168745.

Stergiopoulos V, Hwang SW, Gozdzik A, et al. Effect of scattered-site housing using rent supplements and intensive case management on housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2015;313(9):905–15.

HIV Epidemiology and Field Services Program. Medical care and clinical status among persons with HIV in New York City, 2014. New York City: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2015.

Lim S, Harris TG, Nash D, Lennon MC, Thorpe LE. All-cause, drug-related, and HIV-related mortality risk by trajectories of jail incarceration and homelessness among adults in New York City. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(4):261–70.

Acknowledgements

All authors contributed substantially to the conception, design, analysis, and/or interpretation of data for this paper. All participated in critical revisions, approved this final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The authors thank the New York/New York III supportive housing consumers and agencies, whose participation in the New York/New York III program and completion of applications made it possible to conduct this analysis. We thank multiple agencies that provided data and/or conducted data linkage for this program evaluation, or that provided input about the evaluation. These include the New York City Human Resources Administration, and within it, Customized Assistance Services and the HIV/AIDS Services Administration; the New York State Office of Mental Health; the New York City Department of Correction; the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and within it, the Office of IT Informatics, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control, and Bureau of Mental Health; and the New York City Department of Homeless Services. Thank you to Eleonora Jimenez-Levi and Luis Roberto Rodriguez-Porras for their assistance in preparing the Spanish language abstract.

Funding

At the time of this analysis, all authors worked for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which, in conjunction with New York State, funds and oversees the supportive housing being evaluated. No grants, equipment, or drugs were used for this analysis; no support was received from NIH, Wellcome, or HHMI. Early and partial versions of the findings of this manuscript were presented at the International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence (2016: poster 23; 2017: poster 123).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors are not engaged in any financial or other contractual agreements with potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiewel, E.W., Singh, T.P., Zhong, Y. et al. Housing Subsidies and Housing Stability are Associated with Better HIV Medical Outcomes Among Persons Who Experienced Homelessness and Live with HIV and Mental Illness or Substance Use Disorder. AIDS Behav 24, 3252–3263 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02810-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02810-8