Abstract

In a sample of people with HIV (PWH) enrolled in an alcohol intervention trial and followed for 12 months, we examined the association of changes in days (i.e., decrease, increase, no change [reference]) of unhealthy drinking (consuming ≥ 4/≥ 5 drinks for women/men) with antiretroviral therapy adherence (≥ 95% adherent), viral suppression (HIV RNA < 75 copies/mL), condomless sex with HIV-negative/unknown status partners, and dual-risk outcome (HIV RNA ≥ 75 copies/mL plus condomless sex). The sample included 566 PWH (96.8% male; 63.1% White; 93.9% HIV RNA < 75 copies/mL) who completed baseline, 6-, and 12-month assessments. Decrease in days of unhealthy drinking was associated with increased likelihood of viral suppression (odds ratio [OR] 3.78; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06, 13.51, P = .04) versus no change. Increase in days of unhealthy drinking was associated with increased likelihood of condomless sex (OR 3.13; 95% CI 1.60, 6.12, P < .001). Neither increase nor decrease were associated with adherence or dual-risk outcome. On a continuous scale, for each increase by 1 day of unhealthy drinking in the prior month, the odds of being 95% adherent decreased by 6% (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.88, 1.00, P = 0.04).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Unhealthy alcohol use is a spectrum ranging from drinking above nationally recommended limits to meeting diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders [1]. Prior studies have found that unhealthy alcohol use is common among people with HIV (PWH) [2,3,4], and that prevalence of alcohol use disorders is 2–4 times higher among PWH than among those without HIV [3, 5,6,7]. In samples of PWH receiving healthcare, 27–30% report unhealthy alcohol use and/or meet criteria for alcohol use disorder [8, 9]. Unhealthy alcohol use has serious consequences for the HIV care continuum [10, 11]. It has been associated with decreased care engagement [12], poor antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence [13,14,15,16,17], and decreased likelihood of HIV viral suppression [14, 18,19,20,21]. Consequently, unhealthy alcohol use is implicated as an important driver of morbidity and mortality in PWH [13, 22] and is a key behavioral challenge to address in order to improve HIV care [4, 23] .

In addition to adversely impacting clinical HIV outcomes, unhealthy alcohol use also increases the risk of HIV transmission by reducing inhibition around risky sexual behaviors, including having sex without a condom or having multiple partners [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Alcohol is known to impair risk assessment and sexual negotiation [28, 30]. Studies examining the circumstances of specific sexual encounters have found that individuals who used alcohol prior to sex were significantly more likely to engage in condomless sex [31]. Unhealthy alcohol use and HIV infection also have additive adverse effects on executive functioning, which may mediate health-related behaviors [32].

When PWH do reduce alcohol or other substance use, there is evidence that HIV behavioral and clinical outcomes improve [33,34,35], although few studies have examined outcomes longitudinally. A small number of prior studies of alcohol use patterns among PWH have found a benefit of cutting down on alcohol use, e.g., in an alcohol intervention trial of women with HIV [34], as well as negative outcomes associated with large changes in alcohol consumption among PWH receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration [36, 37]. While prior studies have built a foundation for understanding potential influences of decreased alcohol use on HIV-related outcomes, they are limited in several ways. First, alcohol use reduction may be driven by declines in health [38, 39], and thus the potential benefits of cutting back are not always discernable in HIV cohort studies. Second, prior studies have only examined the association between either unhealthy alcohol use and HIV clinical outcomes or HIV transmission risk behaviors, but not the combination of behavioral and clinical outcomes. Finally, little is known about the influence of changes in alcohol use on HIV behavioral and clinical outcomes in samples of PWH who historically were at greatest risk for HIV transmission but are now relatively healthy, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) with suppressive HIV treatment, and those with private insurance and regular access to care. Longitudinal analysis of alcohol treatment samples that include measures of both ART adherence and viral suppression over time are needed to examine how both increases and decreases in unhealthy alcohol use may impact both HIV behavioral and clinical outcomes, as well as combined behavioral and clinical outcomes, especially in samples of patients for whom HIV is otherwise relatively controlled.

The current study builds on prior investigations by addressing these gaps in the literature. Specifically, we followed PWH longitudinally over 1 year to examine the association between changes in number of days per month of unhealthy alcohol use over time (both decreases and increases) and adverse HIV-related behavioral and clinical outcomes, and their combination, within a primary care sample of PWH recruited to an alcohol-reduction intervention study in a large healthcare plan in the western United States. We anticipated that decreases in frequency of unhealthy alcohol use would be associated with higher likelihood of ART adherence and HIV viral control and lower likelihood of condomless sex over time, but that increases in frequency of unhealthy drinking would have an adverse effect on these same outcomes.

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) health care system. Participants included PWH in a KPNC San Francisco HIV primary care clinic who enrolled in a randomized trial assessing the effects of two behavioral interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use [40]. Study inclusion criteria were based on self-report of any unhealthy alcohol use in the prior year.

The two intervention arms were motivational interviewing (MI) and electronic feedback (EF), both of which used brief treatment models focused on alcohol use reduction; the control arm was usual care (UC). UC included primary care-based implementation of screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment for unhealthy alcohol use [41]. Of the 614 participants enrolled at baseline, 582 (94.8%) completed the 6-month telephone follow-up interview and 583 (95.0%) completed the 12-month telephone follow-up interview. Participants in all three arms showed reduction in alcohol consumption over time, with no overall differences by treatment arm [42]. In the current analyses we only included participants who completed assessments at baseline, 6- and 12-month time points (N = 566).

Measures

Details about measures and data collection procedures for this randomized control trial have been reported previously [40, 42]. Below, we describe measures specific to the secondary analyses presented here.

Primary Predictor: Changes in the Number of Days Reporting Unhealthy Alcohol Use

In the current analyses, self-reported data on frequency of recent unhealthy alcohol use was used to derive a measure of change in the number of unhealthy drinking days in the past month, denoted as ∆UD. Specifically, unhealthy alcohol use was measured based on reported number of days of consuming ≥ 4 drinks (women) and ≥ 5 drinks (men) in a day in the month prior to each interview. This cutoff has been validated as having adequate sensitivity and specificity as an indicator of unhealthy alcohol use [43] and is recommended as an indicator of intervention need based on national clinical guidelines [44]. To estimate ∆UD at each time point, we first subtracted the preceding time point’s unhealthy drinking days’ values from that at the subsequent time point. Depending on whether the difference was positive, negative or zero, we categorized ∆UD into one of three groups representing an increase, decrease or no change in number of unhealthy drinking days, respectively. For example, to estimate ∆UD at 6 months, we subtracted the unhealthy drinking days’ value at baseline from that at 6 months, and if the difference was positive the ∆UD at 6 months represented an increase in comparison with baseline. At baseline, ∆UD was considered missing, since there was no prior time point available for comparison. Secondary analysis examined the effects of a continuous measure of changes in unhealthy drinking days (either increases or decreases).

Study Outcomes

Four dichotomous outcomes were assessed:

Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence

For each time point following baseline, a dichotomous measure of 95% adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) (yes/no) was obtained based on self-report. Participants were asked whether they were currently taking ART medication (yes/no); and “What is your best guess (in %) about how much of your prescribed HIV medications you have taken in the last month?” Responses were dichotomized at ≥ 95%, a widely used cutoff that has been shown to be associated with viral control [17, 45]. Self-report ART adherence has been validated against other methods such as medication refills [46]. Using a self-reported adherence question in our analysis allowed us to simultaneously examine alcohol use and adherence at the same point in time.

Viral Suppression

A dichotomous measure of viral suppression was also measured based on HIV RNA level obtained from the KPNC HIV registry [47]. The registry is populated through electronic monitoring of inpatient, outpatient and laboratory testing databases [48]. HIV RNA levels were measured using lab values closest to the dates of enrollment, 6-month and 12-month follow-up (either before or after these time points), and levels of < 75 copies/mL (lower limit of quantification for the KPNC laboratory) were considered virally suppressed. The viral load measures taken more than 2 years (730 days) before the alcohol assessment dates were set to missing in all analyses that utilized these measures.

Condomless Sex

A dichotomous measure of engagement in risky sexual behavior was derived based on self-report of any condomless sex in the prior 6 months with someone who may or may not have been the participant’s main partner, and who was of negative or unknown HIV status. We chose this measure for the purpose of examining HIV transmission risk. Although condomless sex with individuals of HIV-negative or unknown status might be considered less concerning in light of the overall high rate of viral suppression in the study sample, condomless sex remains important to examine given the potential for variability in viral suppression across time, which implies that even PWH with strong viral suppression may wish to be cautious about condomless sex in order to minimize transmission risk; and for comparability with other studies of unhealthy drinking effects [26, 27].

Dual-Risk Outcome

Finally, higher HIV RNA level and risky sexual behavior can each have unfavorable health effects on PWH and their partners. These outcomes can work synergistically to increase harm because higher HIV RNA level indicates greater HIV infectivity and involvement in risky sexual behavior then increases the chance of transmitting the virus to partners [49]. Thus, we developed a dichotomous dual-risk outcome reflecting a combination of inadequate viral suppression and involvement in risky sexual behavior, in which participants had to have both HIV RNA level ≥ 75 copies/mL and reported condomless sex with a partner of HIV-negative or unknown status. We included this outcome due to its public health importance and because it has rarely been examined among PWH who use alcohol.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics were collected in the baseline survey and included sex (female, male [reference]), age (40–49, 50–59, ≥ 60, 20–39 [reference]), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, Other/Unknown, non-Hispanic White [reference]), income (unknown, < $50 K, ≥ $50 K [reference]) and HIV exposure risk factor (injection drug use, heterosexual/other, unknown, men who have sex with men-MSM [reference]). Although neither intervention resulted in improvements to unhealthy alcohol use relative to usual care in the full study sample, intervention group assignment (MI, EF, UC [reference]) was also considered a covariate due to the potential for group assignment to have small effects on alcohol use and/or clinical outcomes of interest. Baseline number of unhealthy drinking days and baseline values for outcomes of interest (no, yes [reference]) were also considered covariates.

Statistical Analysis

First, we examined the study participants’ baseline characteristics descriptively. We then estimated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of each outcome associated with time-varying change in the number of unhealthy drinking days ∆UD (increase, decrease, no change [reference]). Odds first were estimated unadjusted and then adjusted for covariates using a generalized linear mixed model (PROC GLIMMIX) in SAS 9.4. Statistical significance was defined at P < .05.

Results

The trial study sample included 566 adult PWH. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1; 96.8% of participants were male, the majority (63.3%) were between 40 and 60 years old with an average age of 49.1 years (SD = 10.9 years); 63.1% of participants were non-Hispanic white and 59.7% had annual income ≥ $50,000. The average number of unhealthy drinking days reported in the 30 days prior to baseline was 3.0 (SD = 5.9) days, and 23.9% met DSM-IV criteria at baseline for alcohol dependence. HIV infection was well-controlled with 93.9% having HIV RNA level < 75 copies/mL and 75.8% reporting ART medication adherence ≥ 95%; 40.1% participants reported condomless sex in the 6 months prior to baseline, and 2.3% of participants were categorized as dual-risk (having both HIV RNA level ≥ 75 copies/mL and reporting condomless sex) at baseline. The baseline demographics characteristics of those who were included in the analysis (N = 566) and those who were excluded due to missing data at one or more follow up interviews (N = 48) were comparable. The mean (SD) difference in days between the self-report alcohol measure and viral load assessments were 93.8 (109.2) days for baseline, 113.0 (112.5) days for the 6-month survey, and 120.5 (112.4) for the 12-month survey.

At 6 months, in comparison with the baseline, more than half of the study participants (50.5%) had no change in their unhealthy drinking days; 41.3% had a decrease and 8.1% had an increase. The average number of unhealthy drinking days reported in the prior 30 days at 6 months was 1.2 (SD = 3.5) days. Compared to drinking at 6 months, at 12 months 69.6% of participants had no change in their unhealthy drinking days, 13.4% had a decrease, and 17.0% had an increase. The average number of unhealthy drinking days reported in the prior 30 days at 12 months was 1.4 (SD = 3.8) days.

ORs and 95% CIs from both unadjusted and adjusted models are provided in Table 2. In the unadjusted models, compared with those who had no change in unhealthy drinking, PWH with an increase in unhealthy drinking days trended toward lower odds of ART adherence ≥ 95% (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18, 1.04, P = 0.06) and had higher odds of reporting condomless sex (OR 4.54, 95% CI 2.25, 9.16, P < .0001). A decrease in unhealthy drinking days was associated with a decrease in condomless sex (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.13, 3.25, P = 0.02). No significant association was observed between changes in unhealthy drinking days and HIV RNA level or the dual-risk outcome of having both higher RNA level and reporting condomless sex.

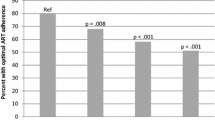

In the adjusted models, reduction in unhealthy drinking days was significantly associated with increased likelihood of viral suppression (OR 3.78, 95% CI 1.06, 13.51, P = 0.04) compared with those who had no change in unhealthy drinking. Compared with the reference group, those who had an increase in unhealthy drinking days had higher odds of reporting condomless sex with someone of negative or unknown HIV status (OR 3.13, 95% CI 1.60, 6.12, P < .001). We did not observe any significant association between changes in unhealthy drinking days and self-reported ART adherence or the dual-risk outcome in adjusted models.

To further understand our results, we conducted a secondary analysis to examine a continuous measure of change in unhealthy drinking days, calculated as the difference between the preceding time point’s number of unhealthy drinking days and those at the subsequent time point. This continuous measure accommodates those with decreases or increases in drinking days over time. For every 1-day increase in unhealthy drinking days comparing time points, the odds of ART adherence decreased by 6% (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.88, 1.00, P = 0.04, Supplementary Table 1). The continuous measure was not associated with other outcomes.

Discussion

In this large sample of PWH receiving regular primary care who were recruited for an alcohol behavioral intervention study, we found that, after adjustment for potential confounders, a reduction in unhealthy drinking days was associated with greater odds of viral suppression, and an increase in unhealthy drinking days was associated with a greater odds of reporting condomless sex with a partner of HIV-negative or unknown HIV status. These findings highlight how changes in unhealthy drinking over time can impact both HIV clinical outcomes and transmission risk.

These findings build on and support the work of prior investigations that have found associations between changes in alcohol use and adverse outcomes among PWH [35, 36, 50]. These studies have examined both effects of increases and decreases in alcohol use. In two recent analyses of Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) data [36], changes in alcohol use over time in both directions, based on change in routine Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) screening scores, were associated with greater HIV disease severity (measured using clinical measures—CD4 and viral suppression—and a comprehensive composite risk index—the VACS Index 2.0) [36, 37, 51]. In both studies, HIV disease severity generally improved over time, and while those with stable alcohol use had the greatest improvements, those with greater increases in alcohol use had smaller improvements in HIV disease severity. Another VACS study used group-based trajectory analysis to examine associations between alcohol use groups and HIV disease based on VACS Index scores [52]. The study identified the greatest likelihood of high HIV severity risk among those with a high likelihood of consistent heavy alcohol use. In an alcohol intervention sample study conducted among women living with HIV, increases in drinking were associated with both improvement in adherence and viral suppression [35]. One survey-based study of medication adherence among Veterans with a history of unhealthy drinking found a temporal and dose–response relationship between drinking days and missed days of ART medication [50].

Although our findings are consistent with prior studies, we found that unhealthy drinking changes did not consistently predict study outcomes as expected. Specifically, only condomless sex was associated with increased drinking and only viral suppression was associated with decreased drinking after adjustment for covariates. And in the main models, neither adherence nor dual risk were associated with changes in drinking over time, though an increase in the number of unhealthy drinking days was associated with decreased likelihood of adherence. It is unclear why we found this pattern, given that the effects of alcohol on patients’ ability to optimally adhere to ART are well-documented [13, 53]. Because viral control and ART adherence are tightly linked (i.e., it is unlikely that the former will be achieved without the latter), the non-significant results with regard to adherence could relate to measurement error. Specifically, our measure of adherence may have resulted in mis-categorization as a result of inaccurate self-report due to social desirability and/or misremembering.

It is also surprising that no association between increased alcohol use and viral suppression was observed, and that the point estimate suggested the possibility that increased alcohol use could improve likelihood of viral suppression. Further research is needed to investigate this issue especially given that most participants were virally suppressed at baseline and relatively few increased their drinking over time, and thus our ability to examine effects of drinking increase is limited. Finally, our findings indicated increased risk of condomless sex associated with increased unhealthy drinking but no association between condomless sex and decreased unhealthy drinking. This divergent finding potentially suggests that the effect of changes in drinking behavior on condomless sex may be mediated by different mechanisms. It is possible that while alcohol use is directly associated with condomless sex, reductions in alcohol use may not, by themselves, be sufficient to increase condom use behaviors.

Despite the somewhat inconsistent results, our findings highlight the adverse effects of increasing days of unhealthy drinking over time on subsequent transmission risk behaviors, even among PWH engaged in care with well-controlled HIV, and suggest several areas for further exploration. In contrast to most prior studies, we examined the effects of changes in number of days of unhealthy drinking on clinical outcomes, and found effects associated with this measure. Some participants identified as decreasing alcohol use over time therefore could still meet unhealthy drinking criteria (based on a categorical definition) at all time points. Potential factors also contributing to the effects we found could include unmeasured changes in health behavior [54, 55] and changes in frequency of intoxication (potentially associated with condomless sex) [24, 56]. Effects of changes in days of unhealthy drinking versus categorical measures, as well as potential factors contributing to the outcomes, are important areas for future study.

Reducing HIV transmission risk behavior among non-virally suppressed PWH is a key focus in effectively ending the HIV epidemic. In this analysis, we did not see any significant associations between change in unhealthy drinking days and the dual-risk measure we created to examine this outcome (i.e., HIV RNA level ≥ 75 copies/mL and engaging in condomless sex), although a lack of statistical power likely limited our ability to examine the longitudinal relationship of changes in unhealthy drinking days with this somewhat rare combined outcome. However, the question of whether changes in unhealthy alcohol use influence both outcomes in tandem warrants further investigation given its potential public health impact.

Study Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge this study was the first longitudinal analysis of the relationship of changes in days of unhealthy drinking over time to HIV clinical outcomes as well as HIV transmission risk behaviors among PWH. The study was conducted in a large primary care-based sample of PWH who reported unhealthy drinking. The study had very high (> 95%) follow-up interview rates and our methods integrated self-report measures and electronic health record data sources to examine study outcomes. In contrast to most prior studies, we examined the potential effects of changes in days of unhealthy drinking using a continuous measure; an approach that can inform potential results of both increases and decreases in alcohol use frequency. However, limitations should also be noted. The study was based in a private health care system in a single geographic region and the sample was primarily MSM, relatively high income, and largely white; and findings may not be generalizable to public samples, those with higher alcohol problem severity, or to women. The study also had greater power for detecting effects of decrease rather than increase in unhealthy drinking over time, because relatively few participants in the sample increased their drinking. Some participants had missing viral load measures, which may have impacted our results in this analysis. Alcohol use and ART adherence measures were based on self-report. Objective measures would be helpful in supporting patient self-report data on condomless sex, e.g., sexually transmitted infection diagnoses. However, such infections could be diagnosed and treated outside the health plan, could be acquired from another PWH, and would not specifically indicate condomless sex from partners of unknown or HIV-negative status; therefore, we believe benefits outweigh the limitations of our self-report measure.

Conclusions

This study examined change in days of unhealthy alcohol use and its association with ART adherence, HIV viral suppression, and condomless sex over time among PWH engaged in care. Results suggest that reduction in the number of unhealthy drinking days could potentially improve viral suppression, but that increases in unhealthy drinking days could increase the likelihood of condomless sex. Increases in unhealthy drinking frequency may also adversely impact ART adherence. Findings highlight the clinical importance of reducing the frequency of unhealthy alcohol use in PWH.

References

Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596–607.

Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(2):179–86.

Cook RL, Sereika SM, Hunt SC, et al. Problem drinking and medication adherence among persons with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(2):83–8.

Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, et al. Alcohol use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection: current knowledge, implications, and future directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(10):2056–72.

Williams EC, Joo YS, Lipira L, et al. Psychosocial stressors and alcohol use, severity, and treatment receipt across human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status in a nationally representative sample of US residents. Subst Abuse. 2017;38(3):269–77.

Chander G, Josephs J, Fleishman JA, et al. Alcohol use among HIV-infected persons in care: results of a multi-site survey. HIV Med. 2008;9(4):196–202.

Silverberg MJ, Chao C, Leyden WA, et al. HIV infection, immunodeficiency, viral replication, and the risk of cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(12):2551–9.

Sullivan LE, Goulet JL, Justice AC, et al. Alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms over time: a longitudinal study of patients with and without HIV infection. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(2–3):158–63.

Crane HM, McCaul ME, Chander G, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with hazardous alcohol use among persons living with HIV across the US in the current era of antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1914–25.

Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800.

Williams EC, McGinnis KA, Edelman EJ, et al. Level of alcohol use associated with HIV care continuum targets in a national US sample of persons living with HIV receiving healthcare. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(1):140–51.

Monroe AK, Lau B, Mugavero MJ, et al. Heavy alcohol use is associated with worse retention in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(4):419–25.

Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, et al. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(3):178–93.

Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(4):411–7.

Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Bashi J, et al. Alcohol use and non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients in West Africa. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1416–21.

Paolillo EW, Gongvatana A, Umlauf A, et al. At-risk alcohol use is associated with antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among adults living with HIV/AIDS. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41(8):1518–25.

Cook RL, Zhou Z, Kelso-Chichetto NE, et al. Alcohol consumption patterns and HIV viral suppression among persons receiving HIV care in Florida: an observational study. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017;12(1):22.

Chander G. Addressing alcohol use in HIV-infected persons. Top Antivir Med. 2011;19(4):143–7.

Shacham E, Agbebi A, Stamm K, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with poor health in HIV clinic patient population: a behavioral surveillance study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):209–13.

Conigliaro J, Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, et al. How harmful is hazardous alcohol use and abuse in HIV infection: do health care providers know who is at risk? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(4):521–5.

Kahler CW, Liu T, Cioe PA, et al. Direct and indirect effects of heavy alcohol use on clinical outcomes in a longitudinal study of HIV patients on ART. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1825–35.

Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, et al. Risk of mortality and physiologic injury evident with lower alcohol exposure among HIV infected compared with uninfected men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:95–103.

Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–5.

Gerbi GB, Habtemariam T, Tameru B, et al. The correlation between alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviors among people living with HIV/AIDS. J Subst Use. 2009;14(2):90–100.

Barta WD, Tennen H, Kiene SM. Alcohol-involved sexual risk behavior among heavy drinkers living with HIV/AIDS: negative affect, self-efficacy, and sexual craving. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(4):563–70.

Przybyla SM, Krawiec G, Godleski SA, et al. Meta-analysis of alcohol and serodiscordant condomless sex among people living with HIV. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(5):1351–66.

Hutton HE, Lesko CR, Li X, et al. Alcohol use patterns and subsequent sexual behaviors among women, men who have sex with men and men who have sex with women engaged in routine HIV care in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(6):1634–46.

Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Cunningham K, et al. Alcohol use predicts sexual decision-making: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S19–39.

Scott-Sheldon LA, Walstrom P, Carey KB, et al. Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among individuals infected with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis 2012 to early 2013. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):314–23.

Parsons JT, Vicioso K, Kutnick A, et al. Alcohol use and stigmatized sexual practices of HIV seropositive gay and bisexual men. Addict Behav. 2004;29(5):1045–51.

Woolf-King SE, Fatch R, Cheng DM, et al. Alcohol use and unprotected sex among HIV-infected Ugandan adults: findings from an event-level study. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(7):1937–48.

Rothlind JC, Greenfield TM, Bruce AV, et al. Heavy alcohol consumption in individuals with HIV infection: effects on neuropsychological performance. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11(1):70–83.

Lucas GM, Gebo KA, Chaisson RE, et al. Longitudinal assessment of the effects of drug and alcohol abuse on HIV-1 treatment outcomes in an urban clinic. AIDS. 2002;16(5):767–74.

Cook RL, Zhou Z, Miguez MJ, et al. Reduction in drinking was associated with improved clinical outcomes in women with HIV infection and unhealthy alcohol use: results from a randomized clinical trial of oral naltrexone versus placebo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(8):1790–800.

Barai N, Monroe A, Lesko C, et al. The association between changes in alcohol use and changes in antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression among women living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1836–45.

Williams EC, McGinnis KA, Bobb JF, et al. Changes in alcohol use associated with changes in HIV disease severity over time: a national longitudinal study in the Veterans Aging Cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;189:21–9.

Williams EC, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, et al. HIV disease severity is sensitive to temporal changes in alcohol use: a National Study of VA Patients With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(4):448–55.

Bilal U, McCaul ME, Crane HM, et al. Predictors of longitudinal trajectories of alcohol consumption in people with HIV. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42(3):561–70.

Kelso-Chichetto NE, Plankey M, Abraham AG, et al. Association between alcohol consumption trajectories and clinical profiles among women and men living with HIV. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(1):85–94.

Silverberg MJ, Leyden WA, Leibowitz A, et al. Factors associated with hazardous alcohol use and motivation to reduce drinking among HIV primary care patients: baseline findings from the Health & Motivation study. Addict Behav. 2018;84:110–7.

Mertens JR, Chi FW, Weisner CM, et al. Physician versus non-physician delivery of alcohol screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment in adult primary care: the ADVISe cluster randomized controlled implementation trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10(26):26.

Satre DD, Leibowitz AS, Leyden W, et al. Interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use among primary care patients with HIV: the Health and Motivation Randomized Clinical Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2054–61.

Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):783–8.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [NIH Publication No. 07–3769]; 2005, updated Jan 2007. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/clinicians_guide.htm. Accessed 6 Oct 2019.

Altice F, Evuarherhe O, Shina S, et al. Adherence to HIV treatment regimens: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Patient Prefer Adher. 2019;13:475–90.

Simoni JM, Huh D, Wang Y, et al. The validity of self-reported medication adherence as an outcome in clinical trials of adherence-promotion interventions: findings from the MACH14 study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(12):2285–90.

DeLorenze GN, Satre DD, Quesenberry CP, et al. Mortality after diagnosis of psychiatric disorders and co-occurring substance use disorders among HIV-infected patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(11):705–12.

Satre DD, Altschuler A, Parthasarathy S, et al. Implementation and operational research: affordable Care Act implementation in a California health care system leads to growth in HIV-positive patient enrollment and changes in patient characteristics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):e76–82.

Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey KB, Johnson BT, et al. Behavioral interventions targeting alcohol use among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(Suppl 2):126–43.

Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, et al. A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(7):1190–7.

Tate JP, Sterne JAC, Justice AC, et al. Albumin, white blood cell count, and body mass index improve discrimination of mortality in HIV-positive individuals. AIDS. 2019;33(5):903–12.

Marshall BDL, Tate JP, McGinnis KA, et al. Long-term alcohol use patterns and HIV disease severity. AIDS. 2017;31(9):1313–21.

Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, et al. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(2):180–202.

Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC. Health behavior predictors of medication adherence among low health literacy people living with HIV/AIDS. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(9):1981–91.

Mangili A, Murman DH, Zampini AM, et al. Nutrition and HIV infection: review of weight loss and wasting in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy from the nutrition for healthy living cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(6):836–42.

Kahler CW, Wray TB, Pantalone DW, et al. Daily associations between alcohol use and unprotected anal sex among heavy drinking HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(3):422–30.

Acknowledgements

We thank Agatha Hinman for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Funding

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, U01 AA021997, K24 AA025703.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Satre, D.D., Sarovar, V., Leyden, W. et al. Changes in Days of Unhealthy Alcohol Use and Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence, HIV RNA Levels, and Condomless Sex: A Secondary Analysis of Clinical Trial Data. AIDS Behav 24, 1784–1792 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02742-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02742-y