Abstract

Miami is a Southeastern United States (U.S.) city with high health, mental health, and economic disparities, high ethnic/racial diversity, low resources, and the highest HIV incidence and prevalence in the country. Syndemic theory proposes that multiple, psychosocial comorbidities synergistically fuel the HIV/AIDS epidemic. People living with HIV/AIDS in Miami may be particularly affected by this due to the unique socioeconomic context. From April 2017 to October 2018, 800 persons living with HIV/AIDS in a public HIV clinic in Miami completed an interviewer-administered behavioral and chart-review cross-sectional assessment to examine the prevalence and association of number of syndemics (unstable housing, low education, depression, anxiety, binge drinking, drug use, violence, HIV-related stigma) with poor ART adherence, unsuppressed HIV viral load (≥ 200 copies/mL), and biobehavioral transmission risk (condomless sex in the context of unsuppressed viral load). Overall, the sample had high prevalence of syndemics (M = 3.8), with almost everyone (99%) endorsing at least one. Each syndemic endorsed was associated with greater odds of: less than 80% ART adherence (aOR 1.64, 95% CI 1.38, 1.98); having unsuppressed viral load (aOR 1.16, 95% CI 1.01, 1.33); and engaging in condomless sex in the context of unsuppressed viral load (1.78, 95% CI 1.30, 2.46). The complex syndemic of HIV threatens to undermine the benefits of HIV care and are important to consider in comprehensive efforts to address the disproportionate burden of HIV/AIDS in the Southern U.S. Achieving the 90-90-90 UNAIDS and the recent U.S. “ending the epidemic” targets will require efforts addressing the structural, social, and other syndemic determinants of HIV treatment and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections have shown overall declining rates in the United States (U.S.) [1] and advances in antiretroviral treatment (ART) have made it possible for adherent persons living with HIV/AIDS to maintain HIV viral suppression. Virally suppressed individuals are not able to transmit the virus and have markedly improved life expectancies [2,3,4,5,6,7]. In addition to ART treatment as prevention (TasP), the advent of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has made a significant contribution to primary prevention of HIV [8]. Despite the overall decreasing rates and unprecedented developments in care and prevention, select geographic regions continue to struggle with continued high rates of HIV and poor HIV/AIDS treatment outcomes.

In particular, the Southern region of the U.S. makes up the majority of new HIV diagnoses (52%) with incidence remaining stable from 2012 to 2016 [9]. The South also has significant prevalence and HIV mortality; in 2015, the South contained 46% of individuals living with HIV in the U.S. and about half of the deaths among people living with HIV (47%). Examining differences within this high-risk geographic area, people of color are disproportionately burdened by HIV making up 77% of new diagnoses in 2017. Specifically, Black, non-Hispanic/Latinx individuals had the highest burden followed by Hispanic/Latinx individuals. Additionally, the Southeastern states of Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana have even higher rates of HIV diagnoses compared to their Southern state counterparts with the state of Florida containing the majority of the HIV “hot spots” (i.e., ranked within the top 10 for incidence and prevalence) including Miami, Orlando, and Jacksonville [9, 10]. Notably, Miami has the highest HIV incidence, the highest HIV prevalence, and is among the top three U.S. cities with the highest AIDS prevalence [9]. In addition, Miami is a city with high health and economic disparities, high ethnic/racial diversity, and relatively low resources compared to other areas of the U.S. making the HIV/AIDS epidemic similar to many developing regions with uncontrolled HIV across the globe [11, 12]. Given this increasing epidemic, understanding factors driving HIV/AIDS within Miami’s unique context is urgent to begin to intervene and mitigate the current public health crisis.

Syndemic theory proposes that multiple, co-occurring psychosocial comorbidities act synergistically to fuel the HIV/AIDS epidemic [13]. In other words, HIV is not a siloed issue, but rather driven by the interrelatedness of disease, mental health, behavior, and social and structural conditions. The complexity of syndemic factors results from the fact that syndemic conditions operate on multiple levels including intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, societal, and structural levels. Examples of syndemic conditions that have been explored as reinforcing HIV risk include depression, substance use, violence (abuse/trauma), stigma, unstable housing, food insecurity, and poverty [14,15,16]. To date, syndemic theory has primarily been used to contextualize HIV acquisition risk among high-risk groups, especially among men who have sex with men [17, 18]. Such research has established a well-supported link between syndemic conditions and HIV risk, including a positive dose–response relationship between number of syndemic conditions and seroconversion [16, 19, 20].

The syndemic conditions of depression, substance use, stigma, trauma, violence, and socioeconomic marginalization have been established as independent risk factors for poor HIV outcomes [21,22,23,24,25,26]. For example, in a prospective study, depression was a significant predictor of a greater rate of CD4+ T cell count decline and increase in HIV viral load [27]. Compared to non-users, all individuals who were using drugs, regardless of pattern of use (e.g., intermittent use, persistent use), had greater odds of having unsuppressed viral load [28] and increases in alcohol drinking significantly predicted lower odds of improving ART adherence and being virally suppressed [29]. Further, stigma, experiencing intimate partner violence, and trauma exposure have also been associated with poor ART adherence and lower odds of viral suppression [21, 30, 31]. Low education and housing instability, indicators of low socioeconomic status, have been associated with faster disease progression, difficulty sustaining viral suppression, poor ART adherence, and overall greater risk of forward transmission [32, 33]. Although these factors have been associated with poor HIV outcomes and subsequent consequences for secondary prevention, research examining the prevalence and correlates of syndemics in people living with HIV/AIDS is relatively understudied. Among persons living with HIV/AIDS, the number of experienced syndemic conditions is associated with lower rates of viral suppression, detectable viral load, decreased medication adherence, and increased healthcare utilization [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. It is especially noteworthy that only one of these studies [43] has been conducted in the Southeastern U.S., and, as discussed above, the Southeastern region of the U.S. is an area in which psychosocial syndemics are high, resources are low, and there is a disproportionate burden of HIV compared to other regions of the country [10].

The present study sought to address this gap by examining the prevalence and correlates of syndemics among persons living with HIV/AIDS who may be at risk for falling off different components of the HIV care continuum: patients receiving care at a public HIV care clinic in Miami. Specifically, we examined the association between the number of syndemics experienced and ART adherence, viral nonsuppression, and, given the importance of treatment as prevention, HIV transmission risk behavior in the context of unsuppressed viral load (i.e., biobehavioral transmission risk).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

From April 2017 through October 2018, 800 persons living with HIV/AIDS in a public, non-profit tertiary care hospital in downtown Miami completed a one-time interviewer-administered psychosocial assessment in either English or Spanish. Inclusion criteria included: (a) clinic patient receiving HIV care, (b) able to give consent, (c) 18 years of age or older, and (d) able to speak and understand either English or Spanish. Viral load data was extracted from medical charts per consent from patients. All study procedures received approval from the University of Miami Institutional Review Board prior to study onset. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Measures

Demographics

Age, race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status were collected.

HIV Biomarkers

Viral load was extracted from electronic medical records and unsuppressed virus was defined as ≥ 200 copies/mL, the clinical point at which transmission may potentially occur (i.e., individuals with < 200 copies/mL cannot transmit the virus) per the Prevention Access Campaign’s Undetectable = Untransmittable consensus statement [44].

Syndemic Conditions

Conditions chosen reflect the syndemic framework which posits that factors at multiple levels, such as intrapersonal (i.e., depression, anxiety, alcohol use, drug use), interpersonal (violence, abuse, trauma), societal (stigma), and structural (low education, unstable housing), drive disease outcomes. Further, conditions were chosen because they have shown independent associations with HIV disease outcomes including poor ART adherence, greater HIV symptoms, decreased CD4 + T-cell count, and increased viral load [21, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33, 45].

-

1.

Depression The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire [46] was used to assess depressive symptoms reflecting major depression diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V [47]. Participants endorsed how often a symptom bothered them on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Items are summed with greater scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. A dichotomous depression syndemic condition variable was created by scoring an individual positive if they indicated clinically relevant depression (score of 5 or greater).

-

2.

Anxiety The anxiety thermometer was adapted from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer [48], a single item self-report measure assessing distress using a visual analog scale from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress). For the current study, the word distress was replaced with “anxiety” so as not to overlap with the questions on the Patient Health Questionnaire. A dichotomous anxiety syndemic condition variable was created by scoring an individual positive if they indicated clinically relevant anxiety (a score of 4 or greater) [49, 50].

-

3.

Alcohol use Substance use was assessed using a measure adapted from the Addiction Severity Index—Lite [51]. Frequency of use in the past 30 days was assessed for alcohol, marijuana, crack, cocaine, heroin, other opioids, amphetamines, hallucinogens, ecstasy/MDMA, sedatives/tranquilizers, and other drugs (0 = no use, 1 = 1 to 2 times, 2 = about once a week, 3 = several times a week, 4 = about every day). Additionally, for those reporting drinking, average number of daily drinks was assessed. An alcohol use syndemic condition variable was created by scoring an individual positive if they reported any binge drinking (4 or more daily drinks) in the past 30 days.

-

4.

Drug use A drug use syndemic condition variable was created by scoring an individual positive if they reported any drug use in the past 30 days.

-

5.

Violence A 9-item adaptation of the Intimate Partner Violence Screening Tool [52] was used to assess lifetime childhood abuse, abuse experienced as an adult, and abuse in the context of a romantic relationship. An adaptation of the Brief Trauma Questionnaire [53] assessed lifetime trauma exposure. A violence syndemic condition variable was created by scoring an individual positive if they reported any abuse or trauma.

-

6.

HIV-related stigma The 6-item Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale [54] was used to assess participant’s perceived stigma associated with their own HIV status. Participants endorsed whether they agreed or not with statements regarding how they feel about their HIV status (e.g., Being HIV positive makes me feel dirty, I am ashamed that I am HIV positive). Patients endorsing at least one stigma item scored positive for the stigma syndemic condition variable.

-

7.

Unstable housing Patients were identified as positive for unstable housing if they reported homelessness or temporary/transitional housing in the past 12 months.

-

8.

Low education Patients were identified positive for low education if they reported less than a high school education.

-

Number of syndemic conditions All dichotomous syndemic condition variables were summed (range 0 to 8) with greater scores indicating greater conditions experienced.

ART Adherence

A single item from Wilson et al.’s [18] 3-item adherence measure (In the last 30 days, on how many days did you miss at least one dose of any of your HIV medicines?) was used to calculate percentage of ART adherence for the past month. Patient’s past month adherence was rated on a scale from 0% (missed all doses) to 100% (perfect adherence). A dichotomous variable representing nonadherence (< 80%) was created.

Biobehavioral Transmission Risk Behavior

A sexual behavior questionnaire assessed types of sexual partners (partner’s gender identity and anatomy), type of sex (anal insertive, anal receptive, or vaginal), condom use, and partner HIV status for the past 4 months. A dichotomous variable was created to identify patients with unsuppressed viral load reporting condomless sex. Any condomless sex with unsuppressed viral load was counted as risk behavior, including those acts with HIV-positive partners, given the risk for HIV reinfection with a second strain (“superinfection”) and associated detrimental effects on clinical outcomes including increased viral load and disease progression [55,56,57].

Data Analysis Plan

Statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 3.5.0 [58].Three logistic regression models, using Firth penalized likelihood method due to separation of binary outcomes, were used to test the association between number of syndemics and: (1) less than 80% ART adherence, (2) unsuppressed viral load (≥ 200 copies/mL), and (3) condomless sex in the context of unsuppressed viral load. All models controlled for age, gender (entered as a dummy variable for cisgender male [vs. cisgender females & gender minorities]), sexual minority status, partnered status (entered as a dummy variable for being in a relationship [vs. those endorsing single, divorced, separated, loss of long term partner, or widowed]), and race/ethnicity (entered as a dummy variable for Black, non-Hispanic/Latinx [vs. everyone else]). For model 2 (outcome = unsuppressed viral load), the model was run in stepwise fashion with the first iteration omitting ART adherence as a covariate, and the second iteration including ART adherence in order to examine the strength of the effect of syndemics on unsuppressed viral load both with and without accounting for adherence. Significant coefficients were transformed and reported in text as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The models were fit using the logistf function in the logistf package (version 1.22).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents patient characteristics. Overall, the sample was a mean of 50 years of age (range 22 to 80), Black, non-Hispanic/Latinx (66%), cisgender male (56%), heterosexual (76%), and single (59%). Patients had an average viral load of 10,499 (range 0 to 1,066,671). Compared to 2018 population estimates for Miami (72% Hispanic/Latinx, 18% Black, non-Hispanic/Latinx, 10% White, non-Hispanic/Latinx) [59], our sample reflects the racial disparities in HIV in Miami. Specifically, despite being 17% of the population of Florida, Black non-Hispanic/Latinx individuals made up 42% of all new HIV diagnoses in Florida [60]; such disparity is reflected in the current sample’s proportions (i.e., 66% Black, non-Hispanic/Latinx). The sample had high prevalence of syndemic factors (range 0-8, M = 3.8, SD = 1.5) including unstable housing (18%), low education (37%), depression (75%), anxiety (50%), drug use (27%), binge drinking (11%), violence (trauma/abuse, 86%), and HIV-related stigma (77%). Figure 1 presents the distribution of syndemic conditions for the sample. Almost the entire sample (99%) experienced 1 + syndemic condition, 95% experienced 2 + conditions, 82% experienced 3 + conditions, 56% experienced 4 + conditions, 32% experienced 5 + conditions, 13% experienced 6 + conditions, 4% experienced 7 conditions, and 1% experienced all 8 syndemic conditions.

Syndemics Predicting Biobehavioral Transmission Risk

Model 1

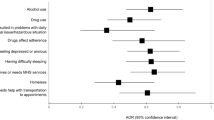

In examining the association of the number of syndemic conditions with ART adherence, the overall model was significant, χ2(6) = 56.61, p < 0.001. Specifically, each one unit increase in number of syndemic conditions was associated with an expected 64% increase in the odds of having less than 80% ART adherence (b = 0.49, SE = 0.09, χ2 = 31.78, aOR 1.64, 95% CI 1.38, 1.98, p < 0.001) while controlling for age, gender, sexual minority status, partner status, and race/ethnicity.

Model 2a

In examining the association of the number of syndemic conditions with unsuppressed viral load, the overall model that did not include ART adherence as a covariate was significant χ2(6) = 55.48, p < 0.001. Specifically, each one unit increase in number of syndemic conditions was associated with an expected 33% increase in the odds of having an unsuppressed viral load (b = 0.29, SE = 0.07, χ2 = 19.78, aOR 1.33, 95% CI 1.17, 1.52, p < 0.001) while controlling for age, gender, sexual minority status, partner status, and race/ethnicity.

Model 2b

When including ART adherence as a covariate, the overall model continued to remain significant, χ2(7) = 103.38, p < 0.001. Specifically, each one unit increase in number of syndemic conditions was associated with an expected 16% increase in the odds of having an unsuppressed viral load (b = 0.15, SE = 0.07, χ2 = 4.70, aOR 1.16, 95% CI 1.01, 1.33, p = 0.030) while also controlling for age, gender, sexual minority status, partner status, and race/ethnicity.

Model 3

In examining the association of the number of syndemic conditions with condomless sex in the context of unsuppressed viral load, the overall model indicated a significant association, χ2(6) = 28.48, p < 0.001. Specifically, each one unit increase in number of syndemic conditions was associated with an expected 78% increase in the odds of engaging in biobehavioral transmission risk (b = 0.58, SE = 0.15, χ2 = 13.43, aOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.30, 2.46, p < 0.001) while controlling for age, gender, sexual minority status, partner status, and race/ethnicity. Results from all models are presented in Table 2.

Post-hoc Analysis

In post hoc analyses, we examined if number of syndemic conditions were significantly different among certain subgroups shown to have HIV outcome disparities using independent samples t tests and one-way ANOVA. In examining syndemic distribution among groups, no significant differences emerged between age groups (under 25 years old vs. 25 years + ; t[11.86] = − 0.69, p = 0.502), gender groups (cisgender males vs. cisgender females and gender minorities; t[798] = − 0.29, p = 0.774), sexual orientations (sexual minorities vs. heterosexual; t[796] = 0.82, p = 0.414), or race/ethnicity groups (F[10, 188] = 0.91, p = 0.527).

Discussion

Findings from the present study of people living with HIV/AIDS in Miami, Florida provided consistent support for the association of greater syndemic burden and ART non-adherence, lower odds of viral suppression, and engagement in biobehavioral HIV transmission risk. In this public HIV clinic in Miami, a domestic epicenter of the HIV epidemic in the U.S., the prevalence of these syndemic conditions was exceptionally high. To date, few studies have examined syndemic theory in the context of persons living with HIV/AIDS, and almost none have been conducted in the Southeast region of the U.S. where HIV rates are disproportionately high compared to other regions of the country. Syndemic theory offers a compelling framework to contextualize Miami’s increasing HIV/AIDS epidemic. In the one study conducted in Miami [43], number of individual level barriers to HIV care (e.g., substance use) and number of system level barriers (e.g., transportation) were investigated as separate predictors of viral suppression. Results showed that only individual levels barriers (having 2 + factors) significantly predicted higher odds of detectable viral load. However, as first conceptualized, syndemic theory suggests that both the individual level syndemic factors and the structural level syndemic factors interact to produce worse disease outcomes [13]. Thus, the current study included multiple levels of syndemic conditions within the same syndemic count to examine the combined effects across levels.

Given the findings that intrapersonal (mental health, substance use), interpersonal (violence), societal (stigma), and structural (low education, unstable housing) level syndemic conditions were associated with factors that contribute to HIV transmission, it would be beneficial to explore intervention designs and theories that are able to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic across levels. In considering how to approach an HIV/AIDS epidemic within a complex environment, such as Miami, it is important to explore multilevel, simultaneous interventions. For example, the modified social ecological model [61] posits that individual, interpersonal, community, and public policy levels all influence the course of HIV/AIDS epidemics in specific regions and should be intervened on with a multipronged approach. Notably, the model posits that the stage of the epidemic (i.e., HIV incidence and prevalence) within an individual’s network and community determines the risk of disease acquisition. Considering the Southeast’s disproportionate rates of HIV, taking this into account may be necessary to reduce HIV incidence. Indeed, examining HIV prevention 25 + years into the epidemic, scholars have brought attention to the notion that employing single level interventions are not sufficient and do not produce substantial nor lasting effects [62, 63]. Although multifaceted interventions are complicated to design and implement, they have the potential to produce large-scale achievements in risk reduction. In conjunction with a multilevel intervention method, promoting a combination of behavioral and biomedical intervention strategies is necessary for maximum impact [64,65,66] given that HIV acquisition and transmission risk depend on both of these factors.

Although this is among the first known studies to examine how syndemic conditions are associated with HIV outcomes in a city with an HIV/AIDS epidemic, limitations should be noted. Data is cross-sectional, limiting the conclusions of temporality. Given that patients were recruited from a public HIV clinic in Miami, the generalizability is limited and may not reflect individuals connected to other types of care in Miami. However, it should be noted that this is an urban safety-net clinic serving the socially marginalized and underserved individuals not consistently connected to care [43]. There is also increasing recognition that an additive model, depending on a summation of binary variables, may not fully capture the dynamic interplay (e.g., severity of each condition) among syndemic conditions that is theorized to fuel the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Although the current study was able to establish additive effects of syndemic conditions, it did not examine multiplicative relationships as some have argued for as needed following a syndemic framework [67]. However, the current study did not have the sample size to test a fully saturated interaction model with the number of interaction terms that would be required. Further, despite the theoretical strength of potentially examining interaction effects [67], additive models provide practical and clinical significance [68]. The binary outcomes in the current sample had low prevalence; although this was statistically adjusted for in the analysis, this should also be considered a limitation and analysis should be replicated with samples with higher rates. Limitations notwithstanding, findings provide evidence for considering the impact of the occurrence of multiple epidemics happening within the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Miami and other afflicted regions.

Additionally, the sample had representation of important subgroups shown to have disparities in HIV risk and outcomes [69,70,71,72] including Black, non-Hispanic/Latinx individuals (66%), Hispanic/Latinx individuals (29%), Black-non-Hispanic/Latinx cisgender women (34%), transgender women (1%), men who have sex with men (21%), and those younger than 25 years old (1.5%). In post hoc analyses, we examined if number of syndemic conditions were significantly different among certain subgroups shown to have HIV outcome disparities. In examining syndemic distribution among age group (under 25 years old vs. 25 years +), gender groups (cisgender males vs. cisgender females and gender minorities), sexual orientations (sexual minorities vs. heterosexual), and race/ethnicities, results showed no significant differences. Findings may reflect the dire and complex HIV epidemic in Miami such that experiencing multiple psychosocial issues is synonymous with HIV infection. Indeed, 95% of the sample experienced 2 + syndemic conditions. However, it remains important to continuously consider moderated analyses to examine groups with greater HIV disparities in order to appropriately contextualize HIV epidemics in other regions of the U.S.

Despite the unprecedented developments in HIV prevention and care that essentially make HIV a chronic disease, certain geographic areas continue to not fully benefit from such advances. In a region of the U.S. with high HIV incidence and relatively high structural barriers to treatment, the complex syndemic of HIV threatens to undermine the benefits of care and are important in attaining public health HIV treatment goals. Achieving the 90-90-90 UNAIDS targets [73] and the recent U.S. “ending the epidemic” targets [74] will require comprehensive efforts addressing the structural, social, and syndemic determinants of HIV transmission and progression.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV/AIDS: Basic Statistics Atlanta, GA; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html. Accessed 17 May 19.

Teeraananchai S, Kerr S, Amin J, Ruxrungtham K, Law M. Life expectancy of HIV-positive people after starting combination antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. HIV Med. 2017;18(4):256–66.

May MT, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Orkin C, Kegg S, et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2014;28(8):1193–202.

Bavinton BR, Pinto AN, Phanuphak N, Grinsztejn B, Prestage GP, Zablotska-Manos IB, et al. Viral suppression and HIV transmission in serodiscordant male couples: an international, prospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet. 2018;5(8):e438–47.

Rodger A, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, Corbelli GM, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in MSM couples with suppressive ART: the PARTNER2 Study extended results in gay men. In: 22nd International AIDS Conference; July 23–27; Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2018.

Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, van Lunzen J, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2016;316(2):171–81.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):830–9.

Spinner CD, Boesecke C, Zink A, Jessen H, Stellbrink H-J, Rockstroh JK, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): a review of current knowledge of oral systemic HIV PrEP in humans. Infection. 2016;44(2):151–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV surveillance report 2017, vol. 29. Atlanta: CDC; 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV in the United States by Region Atlanta, GA; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/geographicdistribution.html. Accessed 15 May 18.

Miami Matters. 2018 Demographics: summary data for county: Miami-Dade: Health Council of South Florida 2018. https://tinyurl.com/miamimatters. Accessed 31 Oct 2018.

Foster S, Lu W. Atlanta ranksworst in income inequality in the U.S; 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-10/atlanta-takes-top-income-inequality-spot-among-american-cities. Accessed 31 Oct 18.

Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):941–50.

Okafor CN, Christodoulou J, Bantjes J, Qondela T, Stewart J, Shoptaw S, et al. Understanding HIV risk behaviors among young men in South Africa: a syndemic approach. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(12):3962–70.

Koblin BA, Grant S, Frye V, Superak H, Sanchez B, Lucy D, et al. HIV sexual risk and syndemics among women in three urban areas in the United States: analysis from HVTN 906. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):572–83.

Santos G-M, Do T, Beck J, Makofane K, Arreola S, Pyun T, et al. Syndemic conditions associated with increased HIV risk in a global sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(3):250.

Mustanski B, Phillips G, Ryan DT, Swann G, Kuhns L, Garofalo R. Prospective effects of a syndemic on HIV and STI incidence and risk behaviors in a cohort of young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):845–57.

Poteat T, Scheim A, Xavier J, Reisner S, Baral S. Global epidemiology of HIV infection and related syndemics affecting transgender people. J AIDS. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S210–9.

Guadamuz TE, McCarthy K, Wimonsate W, Thienkrua W, Varangrat A, Chaikummao S, et al. Psychosocial health conditions and HIV prevalence and incidence in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand: evidence of a syndemic effect. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(11):2089–96.

Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Biello KB, Robertson AM, Safren SA, Coates TJ, et al. The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort of sexually active men who have sex with men. J AIDS. 2015;68(3):329–36.

Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):473–82.

Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):539–45.

Carrico AW. Substance use and HIV disease progression in the HAART era: implications for the primary prevention of HIV. Life Sci. 2011;88(21–22):940–7.

Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Brandson EK, Lima VD, Anema A, Bangsberg DR, et al. The association between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals on HAART. J AIDS. 2009;52(3):342–9.

Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK, Lima VD, Rustad CA, Zhang W, et al. Impact of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status on HIV disease progression in a universal health care setting. JAIDS. 2008;47(4):500–5.

Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Jama-Shai N, Gray G. Impact of exposure to intimate partner violence on CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell decay in HIV infected women: longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0122001.

Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Kumar M, Kaplan L, Balbin E, Kelsch CB, et al. Psychosocial and neurohormonal predictors of HIV disease progression (CD4 cells and viral load): a 4 year prospective study. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1388–97.

Feldman MB, Kepler KL, Irvine MK, Thomas JA. Associations between drug use patterns and viral load suppression among HIV-positive individuals who use support services in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:15–21.

Barai N, Monroe A, Lesko C, Lau B, Hutton H, Yang C, et al. The association between changes in alcohol use and changes in antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression among women living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1836–45.

Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stockl H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2015;29(16):2183–94.

Brezing C, Ferrara M, Freudenreich O. The syndemic illness of HIV and trauma: implications for a trauma-informed model of care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(2):107–18.

Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Rueda S, et al. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;106(1):e1–23.

Poorolajal J, Molaeipoor L, Mohraz M, Mahjub H, Ardekani MT, Mirzapour P, et al. Predictors of progression to AIDS and mortality post-HIV infection: a long-term retrospective cohort study. AIDS Care. 2015;27(10):1205–12.

Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Knowlton AR, Wilkinson JD, Gourevitch MN, Knight KR. Syndemic vulnerability, sexual and injection risk behaviors, and HIV continuum of care outcomes in HIV-positive injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(4):684–93.

Sullivan KA, Messer LC, Quinlivan EB. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS (SAVA) syndemic effects on viral suppression among HIV positive women of color. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(S1):S42–8.

Friedman MR, Stall R, Silvestre AJ, Wei C, Shoptaw S, Herrick A, et al. Effects of syndemics on HIV viral load and medication adherence in the multicentre AIDS cohort study. AIDS. 2015;29(9):1087–96.

Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Garofalo R, Muldoon AL, Jaffe K, Bouris A, et al. An index of multiple psychosocial, syndemic conditions is associated with antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2016;30(4):185–92.

Pantalone DW, Valentine SE, Woodward EN, O’Cleirigh C. Syndemic indicators predict poor medication adherence and increased healthcare utilization for urban HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2018;22(1):71–87.

Harkness A, Bainter SA, O’Cleirigh C, Albright C, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Longitudinal effects of psychosocial syndemics on HIV-positive sexual minority men’s sexual health behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(4):1159–70.

Harkness A, Bainter SA, O’Cleirigh C, Mendez NA, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Longitudinal effects of syndemics on ART non-adherence among sexual minority men. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2564–74.

Blashill AJ, Bedoya CA, Mayer KH, O’Cleirigh C, Pinkston MM, Remmert JE, et al. Psychosocial syndemics are additively associated with worse ART adherence in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):981–6.

Biello KB, Oldenburg CE, Safren SA, Rosenberger JG, Novak DS, Mayer KH, et al. Multiple syndemic psychosocial factors are associated with reduced engagement in HIV care among a multinational, online sample of HIV-infected MSM in Latin America. AIDS Care. 2016;28(sup1):84–91.

Wawrzyniak AJ, Rodríguez AE, Falcon AE, Chakrabarti A, Parra A, Park J, et al. Association of individual and systemic barriers to optimal medical care in people living with HIV/AIDS in Miami-Dade County. JAIDS. 2015;69:S63–72.

Prevention Access Campaign. Consensus Statement: Risk of sexual transmission of hiv from a person living with HIV who has an undetectable viral load 2018. https://www.preventionaccess.org/consensus. Accessed 31 Oct 2018.

Lynn C, Chenneville T, Bradley-Klug K, Walsh ASJ, Dedrick RF, Rodriguez CA. Depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress as predictors of immune functioning: differences between youth with behaviorally and perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1587354.

Spitzer RL. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Distress Thermometer and Problem List for Patients; 2018. https://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/pdf/nccn_distress_thermometer.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct 2018.

Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494–502.

Beck KR, Tan SM, Lum SS, Lim LE, Krishna LK. Validation of the emotion thermometers and hospital anxiety and depression scales in Singapore: screening cancer patients for distress, anxiety and depression. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2016;12(2):e241–9.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O’Brien CP, Woody GE. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168(1):26–33.

Kalokhe AS, Paranjape A, Bell CE, Cardenas GA, Kuper T, Metsch LR, et al. Intimate partner violence among HIV-infected crack cocaine users. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(4):234–40.

Schnurr P, Vielhauer M, Weathers F, Findler M. The brief trauma questionnaire [measurement instrument]; 1999. http://www.ptsd.va.gov. Accessed 31 Oct 18.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the internalized AIDS-related stigma scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):87–93.

Redd AD, Quinn TC, Tobian AAR. Frequency and implications of HIV superinfection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(7):622–8.

Wagner GA, Chaillon A, Liu S, Franklin DR Jr, Caballero G, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder is associated with HIV-1 dual infection. AIDS. 2016;30(17):2591–7.

Sheward DJ, Ntale R, Garrett NJ, Woodman ZL, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C. HIV-1 superinfection resembles primary infection. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(6):904–8.

R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018.

United States Census Bureau. Miami city, Florida; Miami-Dade County, Florida Washington, DC; 2018. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/miamicityflorida,miamidadecountyflorida/PST045218. Accessed 17 May 2019.

Florida Department of Health. Blacks Living with an HIV Diagnosis in Florida, 2017 Tallahassee, FL; 2019. http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/surveillance/_documents/fact-sheet/Black_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed 27 June 19.

Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):482.

Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372(9639):669–84.

Safren SA, Blashill AJ, O’Cleirigh CM. Promoting the sexual health of MSM in the context of comorbid mental health problems. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S30–4.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chovnick G. The past, present, and future of HIV prevention: integrating behavioral, biomedical, and structural intervention strategies for the next generation of HIV prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5(1):143–67.

Bekker L-G, Beyrer C, Quinn TC. Behavioral and biomedical combination strategies for HIV prevention. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(8):7435.

UNAIDS. Combination HIV prevention: tailoring and coordinating biomedical, behavioural and structural strategies 10 to reduce new HIV infections. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2010.

Tsai AC, Burns BFO. Syndemics of psychosocial problems and HIV risk: a systematic review of empirical tests of the disease interaction concept. Soc Sci Med. 2015;139:26–35.

Stall R, Coulter RW, Friedman MR, Plankey MW. Commentary on “Syndemics of psychosocial problems and HIV risk: a systematic review of empirical tests of the disease interaction concept” by A. Tsai and B. Burns. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:129–31.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Risk by Racial/Ethnic Groups Atlanta, GA; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/index.html. Accessed 31 Oct 18.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV and Transgender People Atlanta, GA; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html. Accessed 17 May 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV among women Atlanta, GA; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html. Accessed 17 May 19.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men Atlanta, GA 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html. Accessed 17 May 19.

UNAIDS. 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014.

Azar A. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America; 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/blog/2019/02/05/ending-the-hiv-epidemic-a-plan-for-americahtml. Accessed 8 June 2019.

Funding

The project described was supported by the University Of Miami Developmental HIV/AIDS Mental Health Research Center (D-ARC) funded by P30MH116867 (Safren), the Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine funded by P30AI073961 (Rodriguez [Behavioral, Social Sciences and Community Outreach Core]), the Department of Psychology at the University of Miami, and from K24DA040489 (Safren). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any of the other funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (University of Miami Institutional Review Board; study #20160911) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Glynn, T.R., Safren, S.A., Carrico, A.W. et al. High Levels of Syndemics and Their Association with Adherence, Viral Non-suppression, and Biobehavioral Transmission Risk in Miami, a U.S. City with an HIV/AIDS Epidemic. AIDS Behav 23, 2956–2965 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02619-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02619-0