Abstract

We conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the perceptions of quality of life among people living with HIV who received home-based care services administered through outpatient clinics in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. Data were collected from a sample of 180 consecutively selected participants (86 cases, 94 controls) at four outpatient clinics, all of whom were on antiretroviral therapy. Quality of life was evaluated using the WHOQOL-BREF instrument. In adjusted analysis, those who received home-based care services had a quality of life score 4.08 points higher (on a scale of 100) than those who did not receive home-based care services (CI 95%, 2.32–5.85; p < 0.001). The findings suggest that home-based care is associated with higher self-perceptions of quality of life among people living with HIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Home-based care (HBC) for people living with HIV (PLHIV) and their families plays an essential role in the provision of palliative care [1]. Its aim is to meet their physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs as well as to give aid and support from time of diagnosis to death and bereavement. Quality of life is an essential component of the overall health and well-being of those living with HIV infection. Contributors to an improved quality of life include social support [2,3,4,5], spiritual well-being [3], and a higher level of education [6, 7]. Because quality of life is closely associated with physical, psychological, spiritual and social health, it is often measured in evaluations of the impact of HIV-related interventions in different target populations [8].

The government of Viet Nam has called for provision of HBC services for PLHIV and their families as part of the national response to HIV. Since 2004, HBC models have been supported by several international organizations in Viet Nam [9]. A 2009 rapid situational assessment in Nam identified a wide scope and quality of HBC services as well as limited coverage among five provinces in Viet Nam. However, in interviews and focus group discussions, PLHIV and their caregivers reported highly valuing HBC services, particularly help with emotional support, managing stigma and discrimination, adhering to antiretroviral therapy (ART), treatment of symptoms in the home, and accessing hospital care [10]. In 2010, Viet Nam developed national guidelines for “Community- and Home-Based Care for People Living with HIV” [1].

From late 2010 to December 2015, the Ho Chi Minh City Provincial AIDS Committee (PAC) received financial and technical support from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) to carry out the HBC services at eight-outpatient clinics. The objective: of the HBC services was to improve the quality of life of PLHIV and their families. Each participating clinic had a HBC team, including one team lead who was a member of the clinic health staff and one or two volunteers who were PLHIV or peer educators. They provided training on ART compliance and nursing skills for the volunteers who would provide in-home services, and supported implementation of HBC activities. Services provided to patients and their families in the home included counseling on the prevention of HIV transmission, hygiene, and positive living (taking care of their health and body, having emotional well-being, believing that they can live a normal, productive and healthy life with HIV); and physical care, including symptom management, referral to services for treatment for opportunistic infections (including tuberculosis treatment, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and ART), and support for medication adherence [1]. HBC teams provided family members with training on monitoring HIV treatment adherence, nursing skills, and counseling of their HIV-infected loved ones. HBC teams visited each client once a month; however, teams could increase the frequency of visits based on the client’s needs. Clients could receive the HBC services as long as they wanted.

We conducted this study to determine whether people living with HIV who received HBC services perceived their quality of life to be better than those who did not receive HBC services.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional study was carried out in two of the eight outpatient clinics providing HBC services and two control clinics in Ho Chi Minh City in January 2015. As the intervention home-based care group (HBC group), we selected the two outpatient clinics that had the greatest number of patients who had been on ART for at least 1 year. As the control group, we selected from eight outpatient clinics not providing any HBC, the two with the greatest number of patients on ART for at least 1 year, and in the same geographic location as the two HBC clinics. Other than not offering HBC services, control clinics had the same model and structure of operation and similar staffing profiles. Total patient volume at the four selected clinics ranged from 636 to 1828, and all were freestanding (not hospital-based).

Study Participants

Clinic staff screened all patients for eligibility on the day of their routine clinic visit or medication pick-up. Criteria for inclusion in the study included: (1) age at least 18 years; (2) enrolled at the outpatient clinic and receiving ART treatment at that clinic for at least 1 year; and (3) ability to read, understand and give written consent in Vietnamese to participate in the study. The study was limited to those who had been on ART for at least 1 year in order to ensure greater homogeneity across subjects. During the first year on ART, PLHIV are often faced with many mental health and medical problems, which would make them different from those who had been on ART for some time. This could lead to bias in measuring quality of life. At the HBC clinics, only those patients who had received HBC services for at least 3 months, as determined at the screening stage, were included. Outpatient clinics did not have specific criteria for selecting patients to receive HBC services. All patients received information about HBC services, however HBC services were only provided to patients who requested them. HBC teams respected the rights of PLHIV to choose whether or not they would like to receive HBC. PLHIV and families had the right to continue or discontinue HBC services.

Patients were excluded if they were too acutely ill to be interviewed at the outpatient clinic, if they were not currently on ART, or had been on ART for less than 1 year at their current outpatient clinic. Clients provided written informed consent and completed both interviewer-administered and self-administered questionnaires. Clinical information was abstracted from medical records of consenting clients. All participants were provided with the equivalent of 10 USD to compensate them for their time. The protocol was approved by the Hanoi School of Public Health Institutional Review Board and the Center for Global Health of the CDC.

Sampling

Sample size calculations were based on the comparison between subjects with and without HBC services on the domain of the data collection tool where the smallest effect size was expected to occur. With the sample size of 86 in each group, we had 80% power at an alpha of 0.05 to detect an effect size in any given domain as small as 4%.

At all participating study outpatient clinics, patients on ART were required to pick up their medication at least once a month. Over a three-week period, all patients at each outpatient clinic were screened for eligibility criteria. Participants were consecutively selected at the time of their outpatient clinic visit until the sample quota had been filled. The total number of participants in this study was 180 (86 in outpatient clinics providing HBC services and 94 in outpatient clinics not providing HBC services).

Data Sources

Data were collected from three sources: (1) patient medical records, from which demographic and health information were extracted; (2) a self-administered quality of life questionnaire; and (3) a face-to-face interview establishing participant demographics and assessing their access to and utilization of HBC services.

Primary Study Outcome

The primary outcome of this study was the perceived quality of life of PLHIV. The World Health Organization (WHO) developed a tool to measure quality of life, the WHOQOL-100, from an original pilot assessment, using a unique cross-cultural approach [11]. The WHOQOL-100 contains 100 questions plus an additional four questions that address overall quality of life and general health. In our study, perceived quality of life was measured using the “brief version” of the WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) [12]. The WHO defines “quality of life” as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns,” [12, 13] and has been validated for use in Viet Nam [14]. The WHOQOL-BREF assesses various aspects of an individual’s quality of life, and incorporates questions from four domains: physical (7 items such as activities of daily living, and mobility), psychological (6 items such as bodily image and appearance and negative feelings), social relationships (3 items such as personal relationships and social support), and environment (8 items such as financial resources). These domains are comprised of 24 questions; in addition, the scale includes two items that examine general quality of life (the first asks about an individual’s overall perception of quality of life and the second asks about an individual’s overall perception of his or her health), for a total of 26 items. Questions are answered using a 5-item Likert scale where, in most cases, “1” indicates low, negative perceptions, and “5” indicates high, positive perceptions. Therefore, domain scores are scaled in a positive direction where higher scores denote higher quality of life. Summary domain and total health-related quality of life scores were calculated according to a scoring method developed by the WHOQOL-BREF [13] group.

Study interviewers were four members of the HCMC PAC health staff. They were all trained to obtain informed consent, conduct interviews, and oversee the completion of the self-administered WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. At HBC clinics, an interviewer then asked additional questions about patient access to and use of HBC services. Participants from control clinics were asked if they had received services or participated in activities similar to those offered by the HBC clinics.

Independent Variables

We collected data from medical records on factors that could be associated with the perception of quality of life, including demographic information (e.g., age, gender, education level, and marital status) and clinical information, such as general health status, HIV clinical stage when starting ART, current stage (using CDC classification [15]: asymptomatic, symptomatic, converted to AIDS), year of diagnosis, and means of infection (if known). Additional factors which could potentially confound an association between HBC and quality of life, such as clinical stage of HIV (at the time services were started and currently), length of time HBC services had been utilized, length of time receiving ART, physical measurements (body mass index, viral load and CD4 count), side effects of treatment, and history of co-morbidities, were abstracted from medical records.

Statistical Analysis

We used STATA v12 (College Station, Texas) for all data analyses. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized in total and stratified by study arm, and differences between the two groups were tested using t-tests for normally distributed continuous data, Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous data not normally distributed, and χ2 tests for categorical data. Quality of life scores (ranging from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale) were averaged within each domain, with items reverse-coded where necessary to maintain a consistent directionality. As per WHO instructions, these average scores were multiplied by 4 to get transformed scores on a scale of 4–20, which were then standardized to the WHOQOL 100 using the following equation: (transformed score − 4) * (100/16). A total quality of life score was constructed by summing individual domain scores (on the scale of 4–20), which yielded a maximum total QOL score of 80. Total and domain quality of life scores for both study arms were summarized. Quality of life was treated as a continuous variable, and summary statistics were generated for each domain.

To determine whether receipt of HBC services was associated with a higher mean satisfaction rating for quality of life among the participants, unadjusted linear regression models were performed. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) techniques were utilized to account for clustering by outpatient clinic. Multivariable GEE models were constructed which contained those variables significant in unadjusted analyses at the alpha = 0.05 level, and were additionally adjusted for age and gender.

Results

For our study, we recruited 180 patients from four outpatient clinics, including 86 patients (47.8%) from the two HBC clinics and 94 patients (52.2%) from the two control clinics. Participants were evenly distributed with between 42 and 47 patients from each of the four clinics. In the two HBC clinics, the research team approached 278 patients during 3 weeks of data collection and 86 (31%) patients met the study inclusion criteria. All patients who were asked to participate agreed to do so. At the time interviews were conducted, selected patients had been receiving HBC services for a median (interquartile range) of 24 (7) months and were all currently receiving services.

Overall, the mean (sd) patient age was 36.7 (6.8) years old; 60% of participants were male; and about half were married (Table 1). Nearly 80% of participants reported living above the poverty level, and 70% had less than a high school education. No significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed between the two study arms.

At the time of the interview, patients in the HBC group had spent approximately two more years attending the outpatient clinic and on ART compared to patients in the control group (p < 0.001 for both). Patients in the HBC group were significantly less likely to have started treatment early; almost twice as many patients in the HBC group had started ART at Stage III or IV as compared to those from control clinics (40.7% vs. 22.3%, p = 0.04). However, the median CD4 count at the most recent visits did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.83). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the proportion of participants reporting to have experienced side effects since their last visit. Although more participants in the HBC group had been diagnosed with an opportunistic infection during the prior month (48% vs. 36%), this difference was not significant (p = 0.12).

Participant Quality of Life Scores

The standardized mean (standard deviation, sd) quality of life score across all patients was 51.8 (6.2) out of a maximum score of 80 points (Table 1). Differences across domain scores did not greatly vary, however participants scored highest in the “physical” domain 58.6 (11.3) and lowest in the “psychological” domain 54.4 (11.0), out of a possible 100 points.

Association of Home-Based Care Program with Perceived Quality of Life (Univariate Analysis)

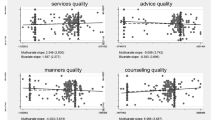

Participants in the HBC group reported an overall mean quality of life score 3.6 points higher than participants in the control group (CI 95%, 1.5, 5.7; p = 0.001; Table 2). We used GEE analysis to examine potential risk factors individually (Table 2). Education was statistically significantly associated with perceived quality of life; those who had attained more than a high school education were more likely to report a better quality of life, with an average score that was 3.2 points higher (p < 0.001) than those who had not gone beyond a high school education. Quality of life was slightly but significantly lower with time enrolled in the outpatient clinic among participants in the HBC group, with scores decreasing by 0.01 on average for each additional month enrolled in the outpatient clinic. Variables such as age, marital status, length of time on ART, recent CD4 count, clinical stage of HIV at the time ART was started, and “currently ill” were not associated with quality of life (p > 0.05. Table 2).

Multivariable Analysis

Covariates that were significant at the alpha = 0.05 level when analyzed individually were included in a multivariable model (Table 2), the model was additionally adjusted for age and gender. In multivariable analysis, participants in the HBC group had a quality of life score four points higher on average than those in the control group, with other factors held constant. In addition, education and months on ART had independent effects on the quality of life. The patients with a higher level of education had a better perceived quality of life, with a score 3.0 points higher on average (p < 0.001); with every one-month increase in length of time in the outpatient clinic, the quality of life score decreased by 0.01 (p = 0.04; Table 2).

Discussion

The results of our study found that patients with HIV who accessed and received HBC services had a higher perceived quality of life score than those who had no access to those services. On average, those in the HBC group had a quality of life score of four points higher than those in the control group. Results of our study supported findings of a systematic review of home palliative care and inpatient hospice care, which were generally found to improve patients’ spiritual well-being, pain and symptom control, and anxiety management [16]. Other positive effects of HBC reported by studies have included reductions in functional decline and rates of institutionalization and mortality [16], as well as self-reported adherence and improvement in pharmacy refills [17].

The absolute score point difference between groups was four, which is clinically significant [18]. Our study also found slightly higher mean quality of life scores among those receiving HBC in all domains: physical, psychological, social, and environmental. This supports previous findings in the literature that HBC provides benefits to PLHIV in a number of ways. It facilitates care in a familiar environment, increases patients’ ability to take ownership of their own problems and life expectancy, reduces the possibility of opportunistic infections, reduces both the macro and micro costs of health care, and has the potential for offering emotionally satisfying palliative care to those with AIDS, thereby improving their quality of life and assisting them in coping with depression and stigma [19,20,21,22,23].

We also found other factors related to quality of life in our study. There was a positive effect of education level on perceived quality of life, independent of access to HBC. This finding supports those reported in other studies conducted in Iran and Thailand in which a significant relationship was found between higher level of education and better quality of life among PLHIV [6, 24]. Although we found a relationship between reporting as “currently ill” and a lowered perceived quality of life, as was reported in other studies [24, 25], this result was not statistically significant. However, this may be due to insufficient power. Finally, number of months in the outpatient clinic was negatively correlated with quality of life. However, quality of life scores of those with access to HBC remained higher, even when adjusted for months attending the outpatient clinic.

There are some limitations of this study. Because the HBC service was rolled out as a small project, the relatively small sample size and the purposive selection of outpatient clinics limit the generalizability of the study results. Also, by limiting the study to those who had been on ART for at least 1 year and those who were literate and so could complete the self-administered questionnaire, we excluded people who were new to treatment or illiterate and therefore might be particularly in need of additional social support. In addition, without a pre/post study design, we were not able to compare quality of life scores before and after receipt of services. In order to encourage more open discussion of care, we did not inquire about specific health care and HBC service providers, although it is likely that the quality of individual care providers would impact perceptions of the quality of that care. Additionally, the participants in the two groups differed clinically, as patients in the HBC group had attended the outpatient clinic and received ART approximately 2 years longer than the control group. We were, however, able to take this into account in the analysis phase of our study. Our results may also be subject to some selection bias, since only patients who had elected to receive HBC are included; we do not have data on those patients who chose not to utilize HBC services in clinics where services were offered.

This study was conducted in Viet Nam in an environment of diminishing external donor support and uncertainty of domestic support and funding for even basic HIV services, including antiretroviral drugs. PAC-supported HBC services were discontinued in December 2015 and no HBC services are currently offered formally in outpatient clinics in Viet Nam. Although PLHIV and their families can receive basic supportive care from peer groups or networks, these are not formally structured and organized, as were the HBC services offered through the outpatient clinics. Nonetheless, our study suggests that HBC services may be beneficial in perceptions of patients’ quality of life. As Viet Nam moves forward to prioritize HIV services for domestic funding, this evaluation data can be helpful to guide supportive care for PLHIV.

References

Ministry of Health/VAAC. National guidelines: community-and home-based care for people living with HIV. 2010.

Bastardo YM, Kimberlin CL. Relationship between quality of life, social support and disease-related factors in HIV-infected persons in Venezuela. AIDS Care. 2000;12(5):673–84.

Liu C, Johnson L, Ostrow D, Silvestre A, Visscher B, Jacobson LP. Predictors for lower quality of life in the HAART era among HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(4):470–7.

Bajunirwe F, Tisch DJ, King CH, Arts EJ, Debanne SM, Sethi AK. Quality of life and social support among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Western Uganda. AIDS Care. 2009;21(3):271–9.

Bekele T, Rourke SB, Tucker R, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25(3):337–46.

Khumsaen N, Aoup-Por W, Thammachak P. Factors influencing quality of life among people living with HIV (PLWH) in Suphanburi Province, Thailand. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. Jan-Feb. 2012;23(1):63–72.

Allavena C, Prazuck T, Reliquet V, et al. Impact of education and support on the tolerability and quality of life in a cohort of HIV-1 infected patients treated with enfuvirtide (SURCOUF Study). J Int Assoc Phys AIDS Care. 2008;7(4):187–92.

Kabore I, Bloem J, Etheredge G, et al. The effect of community-based support services on clinical efficacy and health-related quality of life in HIV/AIDS patients in resource-limited settings in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(9):581–94.

The Goverment of Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Decision of the Prime Minister: Approving the National Strategy on HIV/AIDS prevention and control in Viet Nam till 2010 with a vision to 2020. In: Minister TP, editor. Vol 36/2004/QD-TTg. Ha Noi: The Goverment; 2004. p. 75.

A Joint MoH/VAAC, FHI and PEPFAR Collaboration. Community and Home-based Care in Viet Nam- Findings and recommendations from a rapid assessment. 2009.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. 1992. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018871.htm.

Division of metal health and prevention of substance abuse, World Health Organizaton. WHOQOL-BREF. Geneva. 1998.

World Health Organisation. WHOQOL-BREF. Introduction, admistration, scoring, and generic version of the assessment. Geneva: WHO; 1996.

Tran BX. Quality of life outcomes of antiretroviral treatment for HIV/AIDS patients in Vietnam. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e41062.

Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection–United States, 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-03):1–10.

Harding R, Karus D, Easterbrook P, Raveis VH, Higginson IJ, Marconi K. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with HIV/AIDS? A systematic review of the evidence. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(1):5–14.

Young T, Busgeeth K. Home-based care for reducing morbidity and mortality in people infected with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(1):CD005417.

Den Oudsten BL, Zijlstra WP, De Vries J. The minimal clinical important difference in the World Health Organization quality of life instrument–100. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(5):1295–301.

Layzell S, McCarthy M. Community-based health services for people with HIV/AIDS: a review from a health service perspective. AIDS Care. 1992;4(2):203–15.

Tanzania Commission for AIDS. Home based care in Tanzania. TACAIDS. 2008. http://www.ncbi.n/m.nih.gov/pubamed/16499.

Waran. M. Home-based care in HIV/AIDS, the Indian experience. In: International Conference on AIDS, 2002;vol 142002.

World Health Organisation. Community home-based care. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

Samson-Akpan PE, Ella RE, Ojong IN. Influence of Home-Based care on the Quality of Life of people living with HIV/AIDS in Cross River State, Nigeria 2014.

Nojomi M, Anbary K, Ranjbar M. Health-related quality of life in patients with HIV/AIDS. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11(6):608–12.

Da Silva J, Bunn K, Bertoni RF, Neves OA, Traebert J. Quality of life of people living with HIV. AIDS care. 2013;25(1):71–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the interviewers and the HCMC PAC staff for their contribution to the collection of data. We would like to thank FHI in Viet Nam for providing HBC activities in the outpatient clinics, and CDC in Viet Nam for supporting HBC services and reviewing the study protocol and manuscript. This study was funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under the terms of PS001468. We wish to acknowledge support from the UCSF’s International Traineeships in AIDS Prevention Studies (ITAPS), U.S. NIMH, R25MH064712. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under the terms of PS001468.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of The Ethical Review Board for Biomedical Research Hanoi University of Public Health and ADS of CDC and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bui, Q.T.T., Brickley, D.B., Tieu, V.T.T. et al. Home-Based Care and Perceived Quality of Life Among People Living with HIV in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. AIDS Behav 22 (Suppl 1), 85–91 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2108-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2108-3