Abstract

Many gay, bisexual, and transgender (GBT) people of color (POC) join house and/or constructed family communities, which serve as support networks composed mostly of other non-biologically related GBT/POC. These networks can decrease or increase the risk of exposure to HIV via multiple mechanisms (e.g., providing informal sexual safety education versus stigmatizing family members with HIV, encouraging sexual safety practices versus unsafe escorting, teaching self-care versus substance use) but act to support family members in the face of social and economic hardship. Researchers interviewed ten members of these social networks in the Boston metro area of the US and produced a saturated grounded theory analysis to explore the role of gay family/house networks in HIV risk management. While network members utilized HIV prevention resources, interviewees described how their efficacy was related to the intentions of leadership and strength of kinship boundaries within their community, economic opportunities, and communication skills. Clinical and research implications are discussed.

Resumen

Muchos individuales gay, bisexual, o transgénero (GBT) que al igual son personas de color (PDC) se unen a comunidades caseras o de familias construidas, las cuales sirven como redes de apoyo compuestas mayormente de otros individuales GBT/PDC que no están relacionados biológicamente. A través de varios mecanismos, estas redes pueden disminuir o aumentar el riesgo de ser expuesto al VIH (por ejemplo, ofreciendo educación informal sobre sexo seguro, estigmatizando familiares con VIH, alentando prácticas sexuales seguras en vez de “escorting”, enseñando a cuidar de sí mismo en vez de usar sustancias) pero también funcionan como apoyo para familiares al estos enfrentarse con dificultades sociales y económicas. Los investigadores entrevistaron a diez personas pertenecientes a estas redes sociales en el área metropolitana de Boston en los EUA, y llevaron a cabo un análisis saturado de teoría fundamentada explorando el rol de redes familiares/caseras gay en el manejo de riesgo de VIH. Miembros de estas redes utilizaban recursos de prevención de VIH, pero los participantes del estudio pudieron describir como la eficacia de los mismos estaba asociada a: la fuerza del liderazgo y los límites de afinidad dentro de su comunidad, oportunidades económicas y destrezas de comunicación. Finalmente, se discuten las connotaciones clínicas e investigativas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Disproportionately, gay, bisexual, transgender people, and other Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) are at risk for HIV [1]. The sharpest increases in HIV diagnosis (2005–2014) were found among young Black and Latino MSM aged 13–24, with both groups having increases of about 87 percent [1, 2]. In addition, transgender individuals in HIV testing programs reported rates of diagnosis at 2.6% compared to 0.9% for males and 0.3% for females; the highest rates of diagnosis were found among Black transgender persons [3, 4]. Therefore, identifying effective points of entry to reach high-risk African American MSM (AAMSM) is a top priority in preventing HIV [1, 5, 6].

Constructed non-biological “gay family” networks and “houses” (as termed within these communities) are composed of gay, bisexual, and transgender people of color (GBT/POC) who assume family roles and relationships in relation to each other (e.g., father-son, mother-daughter) to signify deep commitments and provide support, often following rejection from their families of origin [7,8,9,10,11]. Gay adult men as well as transgender women act as fathers, mothers, or sisters within these communities, and young GBT/POC are invited to join these gay family networks (GFN) as sons or daughters. The relational strength of these social networks is evidenced by regular contact among members, enduring support, and the assumption of shared surnames in the community [9]. These families can include extended family members and may cross over state lines. Like families of origin, the networks act to unite a group of people and to communicate norms and values across generations [11]. The present qualitative analysis explores the ways in which HIV risk is negotiated within these networks in the Boston metro area; to date, research has not explored GFNs in the New England region of the US. For the sake of clarity in this paper, the term “family of origin” will be used to indicate biological and legally adoptive families, and gay family network (GFN) will be used to refer to constructed families in these communities (although some members also refer to these GFN simply as their families).

House and Family Networks

GBT/POC individuals in house and family networks face significant sociocultural barriers resulting from discrimination and oppression related to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and gender identity. These converging forces can lead to challenging social and personal conditions, including the lack of economic resources, stigma related to sexual orientation or gender identity, and health challenges [6, 12, 13]. Minority stressors, including the potential for internalized stigma, and experiences of discrimination and/or prejudice [14], interact and can exacerbate each other. The literature on intersectionality, the influence of overlapping minority social identities in relationship to stigma, prejudice, and discrimination, suggests that it can be important to consider how the confluence of racial and sexual minority identities may increase stress [15, 16].

Not only do stressors mount but every layer of stigma means that there are fewer resources available to fight other sources of stigma. For instance, people may find that they are barred from one minority community, where they might otherwise find support, because of a second minority identity. And, they might find that it is harder for them to secure financial resources because they need to overcome multiple stereotypes. The various fronts with which they have to battle compromise how individuals and communities are able to be resilient as well. The members of communities that have participated in our research not only bear intersecting racial and sexual minority stressors, but they typically face oppression due to their socioeconomic status and often their gender identity as well. By recognizing and understanding their intersecting minority stress experiences, HIV supports can be better tailored for individuals with multiple minority identities and for their communities [9, 17, 18].

In some gay and transgender communities of color, house and GFNs are formed to provide support in dealing with intersecting stressors [7, 11, 19]. Because of the heterosexist or genderist rejection from their families of origin or religious communities, these constructed networks are often the sole support network for their members [7, 19]. These groups have been found to draw upon kinship systems and community values found in African American communities, such as pride in self-reliance and racial identity, high regard for family relationships that are inclusive of non-blood relatives who are African American, prizing of community gathering and supports, and flexible family roles [9, 11, 20]. The notion of fictive kinship, enduring ties between people who are not connected by biology or marriage yet provide support for one another, has a central place in this community. These GFNs and houses can enhance resiliency in this manner by providing resources and support for their members [19, 21, 22]. Such networks may provide rich opportunities for HIV intervention and prevention but exploring mechanisms that members deem would be successful in their communities, particularly in non-performance families, has received limited attention [9, 10, 23].

Balls or pageants are forums for dance, fashion, or other artistic talents that can structure support and collaboration for house and GFN members. They include the enactment of gender performances and can take months of rehearsal and preparation [10, 11]. Members tend to pool together resources to afford travel to regional events and they can serve the function of a reunion of those residing in multiple locations. Although both GFNs and house communities are similar in adopting family member positions (e.g., father, daughter), serving social support functions, and sharing a hierarchical family structure [19], they differ in that gay families appear to be smaller and tend to emphasize developmental support over the ballroom or dance/performance competitions that are at the heart of house activity [7, 9]. Although some families may include members who participate in performances, most do not [7, 9]. While houses have been found to be oriented towards preparing members for these competitions, families tend to be oriented towards supporting members to achieve broader life goals (e.g., education, employment, partnering, health) [11]. Families can intersect with house communities, however, depending on the region, sharing members, or having one group subsume the other. Whether or not houses or families participate in ballroom competitions, many members of both attend as observers as these events bring together the larger community to engage in celebration writ large.

The Potential for HIV Intervention

Research within house communities in Los Angeles (L.A.) and New York City has found high rates of HIV seroprevalence and risk behaviors (13–20%) [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Further, these communities include a high proportion of individuals reporting depressive symptoms, homelessness, drug use, joblessness, and sexual and gender minority stigma [11, 27], suggesting that POC in these networks may represent one of the most vulnerable populations within MSM communities.

These networks may hold promise as sites for HIV interventions, serving as culturally-endogenous mechanisms for communicating norms around HIV. Research in L.A. has explored the structures and resiliency among house communities in considering culturally relevant factors to support HIV prevention [8, 10, 19, 23, 28, 29]. They found that risky behaviors acted as a means of escapism and avoidance of financial pressures and other stressors. There is a good deal of variability, however, in the ways that networks regulate risk factors [9, 23].

Engaging opinion leaders from Chicago house communities to deliver risk reduction messages has been associated with reduced number of sexual partners and condomless anal intercourse [30, 31]. Similarly, research in the Southern US on gay family networks [9] has indicated that because family leader sexual safety norms may influence members’ sexual behavior, a focused intervention by leaders could influence sexual safety norms across large social networks comprised of individuals with multiple high-risk factors, shaping future interventions. Efforts to increase attention to HIV in the Northern US were launched with the formation of the House of Latex by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1989 to provide outreach at community balls and HIV counseling to homeless gay and transgender youth [21]. In contrast to house and ball communities, much less is known about the potential role of GFNs in HIV prevention.

Study Objectives

More specific knowledge of GFNs is needed to learn how HIV risk and prevention is currently managed among GBT/POC in these networks. The purpose of this qualitative exploration of interviews with members of these families in the Boston metro area was to examine ways in which participants’ houses and families addressed protective and risk factors related to HIV prevention and intervention. To date, the majority of research on gay family networks has taken place in the LA area, the Midwest, and the Mid-South. We were especially interested to learn from members of these networks in an area of the country where intervention efforts have a history of taking place at balls or house functions, but where GFN structures outside of these settings have not been the focus of HIV intervention or prevention. We conducted the study with the aim of identifying strategies that could lead to the development of culturally-tailored interventions on a national level.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through referrals from a youth organization that provides supports for LGBTQ adolescents of color, including counseling services, case management for homeless youth, community activities, and provision of HIV prevention efforts. To be included in the study, they had to be members of gay houses or constructed families, be people of color, and be over 18 years of age. The participants all lived within the region of Boston, MA (see Table 1 for demographic information). All ten were gay, bisexual, or pansexual-identified individuals who were in GFNs (10) and/or house networks (4). Five participants of color identified as African American or Black, two identified as Black and Hispanic, two identified as Black and multiethnic (unspecified), and one identified as Hispanic. They were all assigned a male gender at birth; eight identified as men and two as transwomen. Their ages ranged between 18 and 29 years old and their roles in the families included mothers, fathers, daughters, sons, and one participant whose identities shifted across networks. The age they first joined a network ranged from 16 until 23. Four had achieved some high school experience, three had completed high school, two had completed college, and one was a current high school student. Their occupations included being a clerk, health service worker, youth worker, teacher, chef, student, and being currently unemployed. The study received institutional review board approval at the university where the primary investigators were affiliated. Participants received $35.00 for their participation in the interview.

Investigators

A description of the LGBTQ-affirmative investigative team is included to provide a context for the analyses. This team consisted of two White European American lesbian-identified psychologists and two African American doctoral students, one who identifies as a bisexual woman and the other as a gay man. All the research team members identified as cisgender. The senior investigators have expertise in both LGBTQ research and qualitative methods, having published, taught graduate-level courses, and served on numerous journal editorial boards, in these areas. They designed this study after conducting research on families in the underserviced US South and were focused on learning how houses and families in New England approached HIV-prevention. They worked to consciously bracket their expectations when studying networks in this region. The doctoral students have interests in intersectional identity research, particularly with respect to ethnic and LGBTQ identities. They were trained in qualitative analysis and co-conducted the unitizing of transcripts under the supervision of the first author, with the second author serving as an auditor.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted based on the main question: “How does being connected to a gay family network influence your attitudes and behaviors related to sexual safety?” Sub-questions asked participants to describe their general network structure and activities as well as sexual risk factors, ways of coping with stressors, risky sex/HIV communications, and testing and safe sex behaviors in relation to their networks. Also, they were asked to describe intervention efforts and recommend routes to intervention. The interviewers were cautious to ask non-leading questions in an open-ended manner to limit biasing. The interviews were conducted in person at a LGBTQ youth organization and were 1–1.5 hours in duration. They occurred in the latter half of 2013. Interviews were digitally recorded and then transcribed by a team of trained graduate students and any identifying information (e.g., network names and place names) was removed prior to coding. The program NVIVO 9.0 was used as a platform for coding data.

Grounded Theory Method

Grounded theory method [32] is an approach in which researchers develop an understanding of a phenomenon that is grounded in empirical observation and analysis. Due to its analytic rigor [33], it has become one of the most frequently used qualitative methods within psychology. There are a number of versions of grounded theory that have been advanced in psychological research as a way to explore subjective experiences and this study uses the approach developed by Rennie [34].

Following this approach, each interview was divided into units that each contained one main idea [35]. Each unit was assigned a label to denote the meaning that it contained (i.e., open coding). Then, researchers used a process of constant comparison in which each of the units was compared with each other unit to generate categories that reflected the commonalities identified. To develop a complex understanding of the relationships between units, they were sorted into as many categories as were relevant to their content (i.e., axial coding). Next, each category was compared to every other category, in turn, and a higher-order level of categories was formed. By repeating this process with each layer of categories, a hierarchical structure of findings was developed. At the apex of the hierarchy, a core category was conceptualized. The core category is the dominant theme in an analysis and articulates the central finding. It is based upon the examination of the data throughout the hierarchy (i.e., selective coding). In grounded theory methods, saturation occurs when further categories do not appear to be forthcoming when new data is added. As the last three interviews did not generate any new categories, this analysis was saturated at the seventh interview and data collection was halted at the 10th interview.

Credibility Checks

Within qualitative research, credibility checks often are used to bolster trustworthiness [33, 36], although the primary establishment of rigor is based within the inductive analytic process [34]. Three forms of checks were used in this study. First, participants were asked a set of questions to assess the thoroughness of the data collection following their interview. They were asked to consider whether there were relevant questions left unasked and whether there was anything about the interviewer (e.g., their race, gender, being a non-network member) that hindered their full disclosure. Overall, participants reported feeling comfortable in the interview but some clarified points of their experience that they thought might be unclear or added new information.

Second, a method of consensus was used in the coding [37] and the analysis came from a process of prolonged joint-engagement [38]. In this process, the first and third authors met weekly for approximately one year to discuss the coding and findings. Researchers dealt with disagreements by consulting the original transcripts and considering whether there might be multiple valid experiences being conveyed. Then the second author acted as auditor and reviewed the findings, providing feedback and suggestions that were considered by the team.

Finally, throughout the study, the process of memoing [32] was used to record shifts in conceptualizations and methods. Memoing also provided a structure for investigators to engage in reflective self-analysis in order to limit the effects of their assumption on the analytic process and further the analysis. It also acted as a forum to take notes on issues to consider together within the team meetings.

Results

The ten transcribed interviews yielded 509 meaning units, which were conceptually organized into a 5-level hierarchy (see Table 2). The following terms will be used to differentiate the levels of the hierarchy: A single core category for the hierarchy was derived from five clusters composed of 17 categories, which themselves contained 76 subcategories. In the descriptions of hierarchy, the following terms will be used to indicate how many interviews led to meaning units that contributed towards the development of a given category: few (1–2 participants), some (3–5), many (6–7), most (8–9), and all (10). These descriptors are best thought of as the number of respondents who considered a theme salient enough to mention during the interview. In these findings, “family of origin” or “biological parents/children” will be added to signify the families within which people were raised and the terms “parents”, “family” and “house” will be used to refer to people in their family or house network within LGBTQ community.

Cluster 1: The Quality of Relationships and Kinship Bonds Moderates Protections Against HIV Risk in Families/Houses, but Stigma Can Make HIV Hard to Discuss

Interviews from all ten participants contributed meaning units to this cluster. Three categories illustrated the relationships in GFNs and families, particularly with respect to issues concerning HIV.

Category 1.1: Families/Houses That Promote Building Healthy Relationships Through Support and Quality Time Spent Together are More Likely to Protect Members From HIV Risk

Most participants (9) relayed that the relationships fostered in families/houses were a positive force in their lives and accompanied HIV risk reduction. Many participants (7) conveyed that network members put aside individual differences for the sake of meaningful bonding and intentional time together, which tempered the effects of societal and family of origin rejection that most members faced as sexual and ethnic minorities. Within this context of mutually developed trust, discussion of sexual safety had more impact, as described by this interviewee:

It can be a positive because if, like I said, you’re so close to your gay family—our house really has a bond…. We [family leaders] talk about, you know, “We can’t stop you because you’re grown but if you’re gonna do it, protect yourself. You know how it is nowadays. It’s not a definite chance but it’s something that you might not want to live with 9 times out of 10.” (P02, Son)

Thus, families and houses were described generally as having a protective effect.

Category 1.2: Families/Houses That Have Strong Parental Leadership and Kinship Bonds are Likely to Lower HIV Risk

Most of the participants described leadership from parents as a protective factor against risky sexual behaviors because parents were so influential (8) and children were likely to respect their parents’ authority and heed their counsel (5). Most (8) interviewees thought that authoritative parents were better able than permissive ones to use their influence to educate gay family members about life, sex, and HIV. As such, some (5) noted how crucial it was for parents to set strict boundaries to maintain their authority:

You have people in the scene who have gay parents who like try to sleep with them. You have gay parents who will like sit down and get high with their children…If you want to be a parent—gay parent or regular parent—like, you still have to have that boundary, and you still have to have that level of respect…. [you can] still have that friendship, but you also have to remember you’re a parent first before you’re that child’s friend. (P05, Son)

Children in less structured families/houses were thought to be at greater risk of engaging in risky sexual practices.

Category 1.3: Mitigation of HIV Risk in Families/Houses is Limited by Poor Relational Quality of Individual Houses and the Stigmatization of HIV in the Family/House Culture

Most study participants (8) indicated that discussions of HIV should occur with more frequency, detail, and gravity. For instance, one participant (P01) said that, while he had talked to his gay siblings about HIV, he found their comments to be flippant: “When they talk about it, they be, you know, joking and stuff.” The stigmatization of HIV positive individuals was thought to prevent meaningful disclosure of HIV status, which could exacerbate risk:

P: Yeah, well people, like in the houses, they’re not really outspoken with their [HIV] status I guess… Like they’re not upfront with… the things they do, until like the aftermath of it… (P09, Daughter)

Many participants (6) thought that members who have HIV were justified in their mistrust of their community. As one interviewee (P03) remarked: “someone that’s HIV positive is going to always be shaded on [criticized] because of their status…. They always going to be looked at different.” Others (4 of 10) conveyed how common it was for gossip about someone’s status to be spread, and some (4) described the paucity of support available to individuals with HIV in the community. This marginalization accentuated the need for more education about HIV.

Cluster 2: Family/House Culture Demands Intense Involvement that can Lead to Competitive Rivalries, Risky Sexual Behaviors, and Escorting, Especially for New Members

Themes from all the participants’ interview responses contributed to this cluster, which contained four categories. Interviewees revealed how the relational bonds within these networks could be engulfing, and how the financial and emotional demands of ballroom competitions could lead to substance use or sales and escorting, propagating unsafe sexual behaviors.

Category 2.1: Houses and Participation in Ballrooms can Increase Risk due to Competition and Rivalries, which Create Community Discord and Social Unrest/Violence

Many participants (7) described the competitiveness between families in the ballroom scene and community discord. Others (5) described how the drama associated with competitions could leave members vulnerable to physical violence and risky behavior:

Balls can be very dangerous. Jealousy. People will cut you in the face because you won a category that has to do with your face. Or people will slip a roofie into your drink and try to take you home. It’s just like any club scene. (P04, Daughter)

The divisiveness undermined the camaraderie and togetherness that made networks protective against HIV risk. One son (P10) reported that safety was often minimized because of the singular focus on competing: “They don’t care about what you’re doing other than that. If you’re escorting, ‘Hey, as long as you’re at the ball!’” Some participants (3) reported how ballroom was so consuming that people lost their prior ethical grounding and began escorting for financial support to continue ballroom participation.

Category 2.2: Relationships in Families/Houses Can Be Transient or Unstable Which May Render Members Vulnerable to Relational Instability and Increase HIV Risk

Some participants (4) noted that disruptions in community togetherness were possible for both houses and families. Without a deep connection and a trusting bond, some GBT parents found it difficult to be vigilant in protecting their children from dangers:

I used to have a lot [of children], but now, like, they just keep on doing their own thing… And the ones that I had, we lost connection so I don’t know…. I leave it to their choice. If you want me to be your parent, I leave it to you.

Participants described how relationships within these networks could sometimes be transient, and some children would go from group to group in search of a stable environment where they could access social support. This placed them in vulnerable positions in the meantime as they lacked needed stability and could fall into escorting or families that dealt in drugs.

Category 2.3: Families/Houses That Practiced Escorting Increased HIV Risk, Especially When Practicing Unsafe Sex

Participants (6 of 10) described escorting as an accepted practice within these communities, despite the practice increasing HIV risk. Some participants (4) reported an association between escorting and the quality of relationships within gay houses and families, but there was disagreement about the direction of this association. While more participants saw it as indicative of unhealthy relationships, one interviewee thought that the need to protect each other from physical violence when escorting drew members closer together.

While some families/houses used protection while escorting, the allure of financial gain made it challenging:

If you’re escorting, you on your own. If you’re escorting you should know to protect yourself or not…. I did it the whole four years that I was in it. I protected myself. But it’s up to them if they want to. And if they are being offered more money, of course they’re going to say, “No, I don’t want to use protection.” (P03, Son/Daughter and Father/Mother)

The general consensus among these participants was that escorting would be difficult to curb considering how many family/house members’ livelihoods depended upon it. Safety in escorting was a more realistic goal.

Category 2.4: More Attention Should be Given to Substance Use in Families/Houses Because it is Common, Decreases Judgment, and Increases Risky Sex Practices

Most participants (9) identified pervasive alcohol and drug use as a major impediment to curtailing HIV within the community. Many spoke of the alterations in judgment and subsequent unsafe sexual behaviors caused by substance use:

I mean when you, when you’re on X [ecstasy]…. And…. I can say this with pure confidence because I’ve been… through it. To where, sober, I’m like “Oh no, I would never!” and then when I’m intoxicated, I’m just like, anything can entice you to go [condomless]. (P02, Son)

A few (2) participants detailed that the most commonly used substances within the community were alcohol and marijuana, but ketamine, cocaine, ecstasy, and prescription narcotics also were thought to be commonly abused.

Some (3) described how GBT parents could be effective agents in protecting gay children from the consequences of substance use without necessarily promoting abstinence. One gay parent (P03) always advised: “Do your pot… that’s fine. You wanna drink? That’s fine. Make sure it’s around me… because I can be aware, and I can just stop anything from happening.” Other participants (4) highlighted the need for more education and counseling within the community regarding the connection between substances and HIV risk.

Category 2.5: Being New to a Gay Family/House Potentially Increases HIV risk Because of Their Lack of Knowledge About HIV or Dangers of the Community

Many participants (6) mentioned how youth new to GFNs or the ballroom community were ignorant of associated dangers (e.g., escorting, substance use) and of safe sex knowledge. Some members (3) expressed outrage at their treatment:

The kid isn’t necessarily wanting a sexual relationship…. If the majority of the kids are having problems with their real family [of origin], of course they’re going to latch on to what you’re saying…. A lot of house members and a lot of the house fathers… will brain-fuck the kids. So like, they tell them “oh,” um, “I’ll give you this” or “you can move in with me”…. But there are a lot of kids that really don’t know what they’re doing but they’re being brain-fucked. (P10, Son)

There was a strong concern that their neediness led younger family members to be sexually manipulated. Ballroom was highlighted as an especially challenging environment with which to get accustomed. A few participants (2) recounted the sexual advances and harassment they experienced when they were new to the ballroom community, particularly at out-of-state balls where casual sex was common.

Cluster 3: Families/Houses Can Lower HIV Risk by Providing Support for Intersecting Marginalized Identities, but Support Can be Mixed for Transgender Individuals

This cluster was composed of four categories and based upon meaning units derived from all of the interviewees. Participants delineated how GFN culture provided sanctuary for individuals experiencing marginalization or stigma on multiple, overlapping levels: race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and gender identity. This experience of marginality occurred within their families of origin, religious and cultural communities, and society at large.

Category 3.1: Families/Houses May Lower HIV Risk by Providing Support Specific to the Needs of GBT/POC That Families of Origin Often do not or Cannot Provide

Most participants (8) indicated that families/houses were crucial to their sense of well-being because they provided nurturance and practical help with day-to-day living. One participant described, “A real parent be passionate and you got to take care of these kids and show them the way or don’t call them your kids” (P06, Mother). Family of origin rejection was not universal, but many (6) described how even relatively accepting families of origin had difficulty identifying with the struggles of being a GBT/POC, which made GFN relationships vital. One participant, for example, maintained a relationship with his family of origin, despite their religious objections to his sexuality: “They’re not accepting of it, but they’ll like… tolerate it, but they’re not for it, because they’re Christian, so they don’t really believe in that lifestyle” (P09). Network parents understood what it took to survive as a GBT/POC youth and were able to provide advice based upon their lived experience of negotiating these barriers.

Category 3.2: Families/Houses Provide Protection From Discrimination and Stigmatization by Providing Refuge for Sexual and Gender Identity Minorities, Which May Lower HIV Risk

There was a strong consensus among most (9) participants that gay houses/families provided protection from multiple sources of stigmatization (heterosexism, transphobia, etc.). For instance, a few (2) participants complained of limited vocational opportunities due to discrimination against sexual and racial minorities, some (3) participants expressed fears of physical harm due to their sexual minority status, and one participant explained that society has blamed HIV/AIDS on gay men. The GFN or houses provided sanctuary from the weight of these accusations:

It’s just that bond - and that, just that time to just, even escape from real life.… They [GBT parents are] always telling me, all their kids, you know, um, “Anytime you need to get away, you just need to clear your head, you just need to sleep for hours… come here. That’s what we’re here for, like, we’re here so you can get away from what we would call ‘the heterosexual normative life.’” (P02, Son)

Family/house members collectively developed resilience by bonding together as a community that celebrates rather than condemns diversity across multiple marginalized identities. This bonding facilitated discussions that were protective against HIV.

Category 3.3: Families/Houses Combat the Increased Challenges of Being a GBT/POC Versus a White LGBTQ Person

Interviews from many participants (7) indicated that the combined marginalization of being both racial/ethnic and sexual/gender minorities led to greater barriers than White LGBTQ people faced. Some of the interviewees (5) expressed the value of being surrounded by other POC who shared their sexual/gender identities:

And my opinion is that I don’t really honestly think that the majority of non-colored people go through most things that colored people go through. And I think that’s what makes our connection a little bit more stronger is because, we’ve gone through those things…like some of the things that [white housemate] complain about we’re like, “Alright, [Housemate],” like, “That’s not even that serious.” Like, “Relax with your little life crisis situation. You ain’t been through shit yet, alright? Calm down. You ever had this happen to you? No? Okay. When you figure out how you would have dealt with that situation, then you would have known how to deal with this situation you’re going through now. Relax. Not that serious.” You know what I’m saying? (P01, Son)

Thus, the intersectionality of ethnic, orientation, and gender identities strengthened connections, which tended to be seen as protective against HIV (see Cluster 1).

Category 3.4: Transgender People are at Increased Risk of HIV Due to Transphobia and Transnegativity, Even Within Some Families/Houses, Which Necessitates Targeted Services

Some participants (4) expressed the need for resources directed towards issues of transnegativity to reduce HIV risk among transgender networkmembers. One interviewee described how transwomen were often unable to access medical care, which increased their HIV risk:

I would assume that [being a transwoman’s] a risk ‘cause… they share, like, not - not always share needles, but sometimes they share needles. And I guess that’s where the HIV plays into it, cause that’s blood to blood…. pumping themselves up with, like, silicone or if they need to take like, um, hormones. (P05, Son)

Two transwomen participants (P04 and P08) spoke of discrimination within family/house culture and how it deleteriously affected their self-esteem. They described how support in families that were exclusively transwomen of color helped them develop resiliency to transnegativity.

Cluster 4: A Lack of Vocational and Communication Skills and Self-Esteem Hinder Resistance to Stigma and Increase Risky Choices in Relationships and Employment

This cluster comprised meaning units from most (8) of the participants who described a variety of inadequacies in skills within the community, primarily due to socioeconomic obstacles and a lack of professional mentoring. This cluster contained two categories that were dissected into psychosocial deficits and lack of vocational opportunities. Participants relayed how these issues collectively diminished individuals’ ability to cope with hardships and limited healthy thriving, ultimately placing members of the community at risk for HIV due to sex exchange based employment.

Category 4.1: Many Members of Families/Houses Have Poor Self-esteem and Lack Interpersonal Communication Skills that Lead to Risky Behaviors and Compromise Resilience

Some of the participants (5) contributed opinions about the source of the relational instabilities within the community, which promoted maladaptive behaviors. Insufficient knowledge about healthy communication and conflict resolution created discord and prevented communication about HIV. One gay father explained this problem as important in many respects:

What I think it might need is some way of teaching people tools to communicate more effectively…. Because there’s always been misunderstandings, and then once a big fight happens or whatever and then everything comes to light and everyone’s like, “Oh, I wish I would have known that two weeks ago, then I wouldn’t have hit her in her face” or “I wouldn’t have thrown the bottle” or something like that or whatever. So if people knew how to communicate effectively… it will, I think, help with less violence. (P07, Father)

Also, two transwomen (P04 and P08) spoke of poor self-esteem associated with being gender identity minorities, while another participant (P09) connected his rejection of safe sex practices to his distrust of others after being hurt. As a remedy to systemic and intra-individual problems, some participants (3) suggested implementing community-wide communications skill education (e.g., through organization workshops and online resources), counseling, and self-reflective exercises (e.g., journaling). Communication skills and self-valuing were thought to allow members to hear sexual safety advice from others and become invested in self-protection.

Category 4.2: A Poor Economy and Insufficient Communication Skills Make it Difficult to Find Employment, Increasing HIV Risky Jobs

Most participants (8) described a link between financial hardship and risky sexual practices, such as escorting. A father explained,

I understand people have to do what they have to do to get money and people have to survive because I’m pretty much surviving myself. I live check by check. I’m fortunate enough to have gone to college… have some degrees under my belt and have a career. But there’s a lot of people in our community… they have to… go below the standard to make money. Whether it be selling their bodies… call person, you know, um, drugs, all that other kind of stuff… it bothers me a little bit because I know… a lot of them have the potential to be and do something. (P07, Father)

The lack of vocational training, communication skills, and economic opportunities were seen as perpetuating escorting and other unsafe behaviors. This gay father further lamented that some members of the gay family/house community did not trust available vocational services because of fear of discrimination against them, or because they catered to White or higher income clients.

Cluster 5: Extensive Efforts to Reduce HIV Risk are Countered by Decisions to Self-Define and Celebrate Sexuality in Accepting Contexts—A Response to Stigma

Units emerging from all ten interviews contributed to this cluster and its three categories. All participants agreed that in the Boston metropolitan area, there was a focus on reducing HIV-risk, both from within families/houses and from local community organizations. Participants described these efforts as beneficial, and highlighted ways to maximize their efficacy.

Category 5.1: Some in Families/Houses Ignore Social Norms and Warnings About Risk, Not Wanting to Relinquish the Thrilling Aspects of Casual or Promiscuous Sex

Many of the interviews (7) contributed units to this category, describing attitudes about sexuality both within and outside GFN culture. Whereas “in [the] middle class and upper class, romance [was thought to be] prominent” (P04), the culture of poverty was thought to be tied to the need for sexual celebration and the pressure to escape:

It’s like… the pleasure of it all, like, with thinking about like, sex being like safe and what not, it just makes it so… like boring to me. I just like it, I don’t know, being… spontaneous I guess. And just like the whole… on the edge kind of thing… So that… makes me not like really think about HIV in the moment until after, like, I’m done. That’s when I think about the whole, like, “I’m stupid, I should never, I should’ve used a condom” and what not, because it’s too late to think about that because I already did. (P09, Daughter)

Sexual risk-taking was reported to be especially high when traveling to out-of-state ballroom competitions where there was an atmosphere of sexual exploration due to availability of novel partners.

Category 5.2: There are Limits to Mitigating HIV Risk in Families/Houses Because of Stubbornness in Personal Choice and Responsibility Regarding Safe Sex Behavior

Many participants (6) contributed to this category, suggesting that there were significant intrapersonal barriers to preventing HIV in the community. They expressed resignation about pervasive denial, rebelliousness, or stubbornness regarding safe sex and framed it as fundamentally about personal responsibility and choice, which inevitably would limit how effective prevention efforts could be. Some participants (5 of 10) thought distorted thinking led people to consider themselves invincible to illness, which was difficult to penetrate. When asked if there was anything that could coax people out of denial, one interviewee was incredulous:

Honestly speaking? No…. Until life really hits them. Like, that’s a lot of what the gay community, they’re very stubborn when it comes to real life situations, because… the real world and the gay community are two different lives…. Because gay life in some aspects is not reality. Like, escorting and getting thousands of dollars in one day is not really reality. Yeah, it’s reality because you did it, but at the same time, you don’t know, like, the consequences behind that… until life really, like, smacks them in the face. (P10, Son)

Similarly, a participant (P09) resisted safe sex advice because of mistrust of messages from others, which he attributed to “the whole bullying thing” from his childhood. He stated: “I just like push a lot away, to keep it from like, hurting I guess.” He wondered if people were simply jealous of his sexual freedom, questioning if they were “trying to be helpful” or “trying to… bring [him] down.” It was difficult for him to trust that safe sex messaging was protective.

Category 5.3: Continuing, Improving Upon, and Incentivizing HIV Education and Workshops May Increase Knowledge and Decrease HIV Risk

Most participants (8) expressed appreciation for the safe-sex education already occurring in the Boston area. They identified an array of educational efforts, including (a) conference and community organization workshops; (b) creative incorporation of sexual safety messages (flyers, presentations, activities) at ballroom events; (c) widespread communication at multiple levels, from ballroom leaders, GBT parents, siblings in families/houses, LGBTQ community organizations, etc.; and (d) distribution of free condoms and subsidized STI testing at LGBTQ organizations, health facilities, and mobile treatment centers. Participants emphasized the importance of programs tailored to the needs of the community (e.g., free condoms, sponsoring existing community activities with an educational component, offering free space to houses for ballroom practices, and providing educational materials and vouchers for food or events).

Current efforts have been so effective that some indicated the region was saturated with factual information, and they did not know if further efforts would be beneficial. However, many saw clear room for improvement, especially considering that several participants highlighted significant misconceptions among family/house members:

Within the scene, we just need more like… the right information…. Like a couple of weeks ago I was having a conversation with somebody and they said, “Well, I don’t really get tested like that, because I feel fine.” I’m like, “Well, you can’t always rely on feeling fine.” I was like, “Did you know specifically in males… like you could have gonorrhea or chlamydia for years and not have symptoms….” So it’s like, just little things like that. (P05, Son)

In addition to more applicable knowledge, interviewees thought that current efforts could be improved through: greater emphasis on substance use; more direct, less clinical language; sensitivity to the need for anonymity, especially for individuals with HIV who sometimes avoided workshops for fear of having their status exposed; and messages delivered by those within the community (e.g., GBT/POC who have HIV) versus professionals. Participants who had training in HIV prevention described being able to better educate their own families/houses as a result of the knowledge they received through organization connections. Finally, using GFN leaders and prominent parents to communicate sexual safety messages was thought to be more influential than outside messengers.

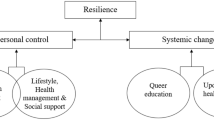

Core Category: Family/House Networks Strengthen Their Members in the Face of Social, Familial, and Economic Stressors by Creating Normative Systems That Generate New Values That Influence HIV Risk

The clusters that emerged from these ten interviews demonstrated how families/houses provided support for GBT/POC in the face of their intersecting, marginalized identities. Members described developing resiliency to discrimination and socioeconomic hardships by resisting out-group norms and developing in-group norms that affirmed their struggles. These new norms could decrease HIV risk by facilitating trusting relationships within families that emphasized safe sex, promoted personal pride, and celebrated their identities. GBT parents were identified as particularly effective agents in reducing HIV risk in the community because of their influence and credibility, but not all parents educated their families/houses about HIV. When the network norms helped members cope via illicit substance use, unrestrained sexual activity, and escorting practices, sexual safety decreased. Moreover, stigmatization of individuals with HIV exacerbated risk by creating a culture of shame that precluded disclosure and discussion of HIV. Sexual safety interventions that recognized these both engulfing and protective normative systems were thought to be better able to influence individuals in these networks. The implications of this understanding will be considered in the following section.

Discussion

This study found that GFNs and house networks of GBT/POC provided alternate systems of support that embraced the intersectional identities of their members in the face of severe minority stressors. These systems of support could be a life-line for some and their engagement in dramatic arts could be compelling. In order to maintain involvement, youth might engage in activities that helped their network survive or that allowed themselves or their network to afford to travel to and participate in balls or pageants. Some of these activities, such as escorting and illegal drug use and sales, could increase the likelihood of risky sexual behaviors dramatically. In addition, community norms were in place that could indirectly increase risk. For instance, the celebration of sex, the holding of events where alcohol and drugs were common, low employment rates, and distrust of external authority could compromise the effectiveness of the sexual safety messages that networks and external agencies promoted.

Developing Interventions That Work with GFNs Strengths

The family and house networks build upon positive traditional values, such as respect for elders and responsibility for other family members in African American cultures [39], and are invaluable assets in conjunction with biological and ethnic minority communities. Many participants described the struggles they had within their families of origin to be understood as sexual minorities, however, they tended to stay in connection with families of origin and utilize GFNs and houses as supplemental constructed families from which they could draw support and had freedom to engage into varying degrees.

Because of the strong support that these networks provide for their members, researchers may wish to consider ways to intervene that draw upon their strengths and potential. In the results (see Category 5.3), the participants described many forms of education that could be useful, however, offering these in a culturally-congruent manner is central. For instance, some local organizations have been effective in drawing in members of the community for condom use education, counseling, and social services by offering them a place to learn dances (e.g., j-setting) or practice routines. Because some of the high-risk factors are driven by economic needs (e.g., escorting, drug trade), it may be that culturally tailored HIV prevention could be integrated with employment/job skill training programs that some GFN leaders suggested would be helpful for their families.

Holding family leader education trainings to support members to hook up or escort safely can likewise be key. Recognizing that casual sex is more likely at balls or pageants, participants described that having condoms at these events and messages related to sexual safety could be helpful. They also described learning escorting strategies such as escorting in pairs, learning how to insist upon condom use at the beginning of a transaction, and using key words to signal danger to each other as culturally congruent interventions. Formalizing the teaching of these harm-reduction strategies can allow for their more thorough dissemination in these communities.

Developing Interventions to Change Network Norms

While the previous interventions support the current community values and activities, previous research also has recommended interventions that change community norms by working within them. Because peer condom-use norms have been found to influence condom use [40, 41], the deliberate development of GFN community expectations of condom use could be beneficial. The current research supports the findings that networks, and especially parents, influence the use of safe-sex behaviors among their children (9). Social network level interventions have been effective means of HIV prevention [4, 42, 43]. Because of their trusted roles and social credibility, GFN leaders are in singular positions to influence their community norms. Providing education and support to parents and prominent network members could encourage them to shift community standards. Previous research has found that both the number of sexual partners and frequency of condomless anal intercourse has been reduced by community leaders communicating risk prevention messages [30, 31], and has found that parents are invested in these efforts (9).

At the same time, many members described that there would always be participants who would not engage in sexual safety practices. New and transgender community members appeared to be especially in need of support and participants suggested that others might take advantage of them by encouraging them to engage in unsafe activities. Targeting education on issues related to gender diversity toward GFNs and inclusivity of the needs of transgender members could be a useful line of intervention. Moreover, working with parents and high-profile community members to reduce the stigmatization of individuals with HIV, which exacerbates the risk to all members by creating a culture of shame, could help to foster HIV disclosure and discussion of HIV. Piloting vocational interventions, developing interpersonal communication skills programs in the face of high levels of rejection and trauma, and shaping community-driven strategies to reduce stigma and strengthen sexual safety norms could be useful strategies that also could reduce shame if driven by community members. By engaging multiple strategies and working with the strong community capacity for mutual care, strength, and resilience of its members, HIV interventionists might be able to support these communities to tailor programs that address their needs.

Finally, it was notable that the discussion of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) did not emerge as a potential area of intervention in these interviews. Although awareness of PrEP has increased among GBMSM, willingness to take PrEP has lagged among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men [44]. GFN leaders may be particularly effective educators about the use of PrEP by reducing stigma surrounding its use by community members, reducing myths about the prophylactic, maintaining medical adherence, and emphasizing the use of condoms in tandem with PrEP.

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

The setting of this study was the Boston metropolitan region. Although its findings appear to support the research conducted upon networks within other regions of the country [9, 11, 19, 21,22,23, 26], most of this body of research is within urban areas and it is hard to assess how gay family networks may function in rural contexts. Also, while the vast majority of these networks are composed of GBT/POC, the families did sometimes report having known a person in a network who was White, lesbian, or heterosexual, and their experiences might be different than the ones described here.

Within the interviews, it was challenging to identify any discrete differences between houses and families. The participants who were in houses also were in family networks. The description of differences were in line with the existing understanding within the literature in which families tend to be smaller, more intimate, and more focused on the general developmental goals of the children (e.g., completing high school, developing positive interpersonal relationships) while houses provided support but had a stronger focus on organizing members to win competitions [7, 11].

At the same time, the study design included a number of credibility checks. In addition, the data reached saturation, suggesting that the number of participants was sufficient to develop a comprehensive analysis. The findings also provided guidance for considering intervention development within this population characterized by so many intersecting high-risk features. The study is unique in that it is one of the few that specifically focused on strategies for HIV prevention identified by GFN members. Although a number of HIV risks emerged in relationship to GFNs and Houses, many strengths were identified for utilization of GFNs in HIV prevention and intervention efforts.

References

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Trends in HIV diagnoses, 2005–2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/hiv-data-trends-fact-sheet-508.pdf. 2016a.

Balaji AB, Bowles KE, Binh CL, Paz-Bailey G, Oster AM. High HIV incidence and prevalence and associated factors among young MSM, 2008. AIDS. 2013;27:269–78.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV among transgender people. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/transgender/index.html. 2013.

Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender person in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):1–17.

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC. 2010.

Centers for Disease Control. HIV among gay and bisexual African American men. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html. 2016b.

Dickson-Gomez J, Owczarzak J, St. Lawrence J, et al. Beyond the ball: implications for HIV risk and prevention among the constructed families of African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(11):2156–68.

Holloway IW, Traube DE, Kubicek K, Supan J, Weiss G, Kipke MD. HIV prevention service utilization in the Los Angeles house and ball communities: past experiences and recommendations for the future. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(5):431–44.

Horne SG, Levitt HM, Sweeney KK, Puckett JA, Hampton ML. African American gay family networks: an entry point for HIV prevention. J Sex Res. 2015;52(7):1–14.

Kubicek K, Beyer WH, McNeeley M, Weiss G, Omni LFTU, Kipke MD. Community-engaged research to identify house parent perspectives on support and risk within the house and ball scene. J Sex Res. 2013;50:178–89. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.637248.

Levitt HM, Horne SG, Puckett J, Sweeney KK, Hampton ML. Gay families: challenging racial and sexual/gender minority stressors through social support. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2014;11(2):173–202.

Barrow RY, Berkel C, Brooks L, Groseclose D, Johnson DB, Valentine JA. Traditional sexually transmitted disease prevention and control strategies: tailoring for African American communities. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:S30–9.

Ford CL, Whetten KD, Hall SA, Kaufman JS, Thrasher AD. Black sexuality, social construction, and research targeting “The Down Low” (‘The DL’). Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:209–16.

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2013;1(S):3–26.

Crenshaw KW. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43:1241–99.

Moradi B, DeBlaere C. Replacing either/or with both/and: illustrations of perspective alternation. Couns Psychol. 2010;38:455–68.

Bowleg L. When black + lesbian + woman ≠ black lesbian woman: the methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–25.

Purdie-Vaughn V, Eibach RP. Intersectional invisibility: the distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles. 2008;59:377–91.

Kubicek K, McNeeley M, Holloway IW, Weiss G, Kipke MD. It’s like our own little world: resilience as a factor in participating in the ballroom community subculture. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1524–39.

Hill Collins P. It’s all in the family: intersections of gender, race, and nation. Hypatia. 1998;13(3):62–82.

Phillips G II, Peterson J, Binson D, Hidalgo J, Magnus M. House/ball culture and adolescent African American transgender persons and men who have sex with men: a synthesis of the literature. AIDS Care. 2011;23(4):515–20. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.516334.

Hwahng SJ, Nuttbrock L. Sex workers, fem queens, and cross-dressers: differential marginalizations and HIV vulnerabilities among three ethnocultural male-to-female transgender communities in New York City. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2007;4(4):36–59.

Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Supan J, Weiss G, Schrager S. Laying the groundwork for an HIV prevention intervention: a descriptive profile of the Los Angeles house and ball communities. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):1068–81.

Marks SM, Murrill C, Sanchez T, Liu K, Finlayson T, Guilin V. Self-reported tuberculosis disease and tuberculin skin testing in the New York City house ballroom community. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1068–73.

Murrill CS, Liu KL, Guilin V, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risk behaviors in New York City’s house ball community. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1074–80.

Sanchez T, Finlayson T, Murrill C, Guilin V, Dean L. Risk behaviors and psychosocial stressors in the New York City house ball community: a comparison of men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:351–8.

Austin EL, Lindley LL, Mena LA, Crosby RA, Muzny CA. Families of choice and noncollegiate sororities and fraternities among lesbian and bisexual African-American women in a southern community: implications for sexual and reproductive health research. Sex Health. 2014;11:24–30.

Schrager SM, Latkin CA, Weiss G, Kubicek K, Kipke MD. High-risk sexual activity in the House and Ball community: influence of social networks. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):326–31.

Wong CF, Schrager SM, Holloway IW, Meyer IH, Kipke MD. Minority stress experiences and psychological well-being: the impact of support from and connection to social networks within the Los Angeles House and Ball communities. Prev Sci. 2013;15:44–55.

Hosek SG, Lemos D, Hotton A, et al. An HIV intervention tailored for black young men who have sex with men in the House Ball community. AIDS Care. 2015;26(3):355–62.

Lemos D, Hosek S, Bell M. Reconciling reality with fantasy: exploration of the sociocultural factors influencing HIV transmission among Black young men who have sex with men (BYMSM) within the house ball community: a Chicago study. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2015;7(1):64–85.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

Fassinger RE. Paradigms, praxis, problems, and promise: grounded theory in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):156–66.

Rennie DL. Qualitative research as methodical hermeneutics. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):385–98.

Giorgi A. The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press; 2009.

Elliott R, Fischer C, Rennie DL. Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br J Clin Psychol. 1999;38:215–29.

Hill CE, Knox S, Thompson BJ, Williams EN, Hess SA, Ladany N. Consensual qualitative research: an update. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):196–205.

Denzin NK. The art and politics of interpretation. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. p. 500–15.

Sudarkasa N. Black families. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1997.

Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Impact of beliefs about HIV treatment and peer condom norms on risky sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. J Community Psychol. 2006;34:37–46.

Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Weakliem DL, Madray A, Mills RJ, Hughes J. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Rep. 1998;113:42–57.

Garfein RS, Bailey S, Golub ET, for the DUIT Study Team, et al. Reduction in injection risk behaviors for HIV and HCV infection among young injection drug users using a peer-education intervention. AIDS. 2007;21:1923–32.

Mackesy-Amiti ME, Finnegan L, Ouellet LJ, et al. Peer-education intervention to reduce injection risk behaviors benefits high-risk young injection drug users: a latent transition analysis of the CIDUS 3/DUIT Study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2075–83.

Grov C, Rendina J, Whitfield THF, Ventuneac A, Parsons JT. Changes in familiarity with and willingness to take Preexposure Prophylaxis in a longitudinal study of highly sexually actice gay and bisexual men. LGBT Health. 2016;3:252–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We would like to thank Marta Pagan-Ortiz for her translation of the abstract into Spanish.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levitt, H.M., Horne, S.G., Freeman-Coppadge, D. et al. HIV Prevention in Gay Family and House Networks: Fostering Self-Determination and Sexual Safety. AIDS Behav 21, 2973–2986 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1774-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1774-x