Abstract

Seroadaptive behaviors are traditionally defined by self-reported sexual behavior history, regardless of whether they reflect purposely-adopted risk-mitigation strategies. Among MSM attending an STD clinic in Seattle, Washington 2013–2015 (N = 3751 visits), we used two seroadaptive behavior measures: (1) sexual behavior history reported via clinical computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) (behavioral definition); (2) purposely-adopted risk-reduction behaviors reported via research CASI (purposely-adopted definition). Pure serosorting (i.e. only HIV-concordant partners) was the most common behavior, reported (behavioral and purposely-adopted definition) by HIV-negative respondents at 43% and 60% of visits, respectively (kappa = 0.24; fair agreement) and by HIV-positive MSM at 30 and 34% (kappa = 0.25; fair agreement). Agreement of the two definitions was highest for consistent condom use [HIV-negative men (kappa = 0.72), HIV-positive men (kappa = 0.57)]. Overall HIV test positivity was 1.4 but 0.9% for pure serosorters. The two methods of operationalizing behaviors result in different estimates, thus the choice of which to employ should depend on the motivation for ascertaining behavioral information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Seroadaptive behaviors, such as serosorting (i.e. choosing partners based on a partner’s perceived HIV status) and seropositioning (i.e. choosing an insertive or receptive anal sex role based on a partner’s perceived HIV status) are common among men who have sex with men (MSM) and typically involve condomless sex [1–8]. Serosorting and many, but not all, seroadaptive behaviors are associated with a lower risk of HIV than condomless anal intercourse (CAI) with an HIV-positive/unknown-status partner but a higher risk of HIV than consistent condom use [1, 4, 9–11].

Though seroadaptive behaviors have been recognized since the 1990s, how these behaviors should be defined is still a topic of debate. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines serosorting as “choosing a sexual partner known to be of the same HIV serostatus, often to engage in unprotected sex, in order to reduce the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV” [12]. However, nearly all studies, including those from which HIV risk estimates were obtained, have defined seroadaptive behaviors based only on a man’s reported sexual behavior history. For example, men who have condomless anal sex only with men of the same HIV status are defined as serosorters. This definition, henceforth referred to as a “behavioral definition” or “behavioral measure”, defines men as serosorting even if their behavior did not reflect a purposive decision to reduce the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. Perhaps the behaviors merely reflect a limited availability of partners or a partner’s preferences for sexual positioning or condom use, rather than the individual’s attempt to conform to an explicit HIV prevention strategy. As an alternative measure, some studies have employed a definition that explicitly asks men if they purposely adopted behaviors based on their partner’s HIV status (henceforth referred to as a “purposely-adopted definition” or “purposely-adopted measure”). Though this latter definition is more closely aligned with that of CDC, the behaviors that men report purposely adopting to reduce the risk of HIV transmission or acquisition do not necessarily align with their reported sexual behavior history [13, 14]. Thus it is unclear if measuring purposely-adopted behaviors will provide a better estimate of HIV risk or be more useful for behavioral counseling compared to only measuring the behaviors themselves.

Only a few studies have used a combination of behavior and purposely-adopted definitions of seroadaptive behaviors in the same population [13–16]. A longitudinal study of San Francisco MSM found that few seroadaptive behaviors were the result of intentional HIV risk-reduction strategies [15], and an Internet-based study noted that only 15–52% of seroconcordant partnerships were intentional or purposive [16]. While these studies suggest that the two definitions of seroadaptive behaviors are distinct, neither directly compared the two definitions as independent measures of seroadaptive behaviors. Thus, the extent to which these two measures provide different estimates of the prevalence and risks/benefits associated with seroadaptive behaviors remains uncertain.

There were two primary objectives of this study. First, we used two separate surveys in the same patient population—one that collected sexual behavior history and a newly developed survey to collect information on purposely-adopted seroadaptive behaviors—to compare the prevalence and agreement of two measures of seroadaptive behaviors (behavior definition vs. purposely-adopted definition). Second, using our new survey, we examined the risk of testing newly HIV/STI positive for several purposely-adopted seroadaptive behaviors.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a cross-sectional study of MSM attending the Public Health-Seattle & King County (PHSKC) STD clinic enrolled from February 2013 to June 2015. Detailed recruitment and enrollment procedures are described elsewhere [17]. Briefly, all patients presenting to the PHSKC STD clinic for a new problem visit are asked to complete a clinical computer-assisted self-interview (clinical CASI) which includes information on demographics, sexual behaviors, drug use, and HIV testing history. Men who reported in the clinical CASI that they had >1 male sex partner in the prior 12 months were eligible to enroll in the study. Immediately after completion of the clinical CASI, participants completed a 10 min research CASI which queried men on their purposely-adopted seroadaptive behaviors in the prior 12 months, as described below. Data from the clinical CASI and research CASI were subsequently linked. Participants enrolled in the first 6 weeks of the study were paid $5 for their participation, but this increased to $10 for participants enrolled thereafter. Men were allowed to participate in the study more than once. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by our institution’s Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Data Collection and Measures

Data from the clinical CASI were used to construct the behavioral definition of seroadaptive behaviors. The sexual behavior information collected in the clinical CASI included sexual role (insertive or receptive) stratified by partner HIV status (HIV-positive, HIV-negative and unknown status), and condom use with partners stratified by sexual role and HIV status of partners. For example, “Have you topped anyone who was HIV-positive in the last 12 months?” and (for men who indicate “yes”) “In the last 12 months how often have you used condoms when topping HIV-positive partners?” Information about sexual role with partners was collected as yes/no, while condom use information was collected as always/usually/sometimes/never [4, 18].

Data from the research CASI were used to construct the purposely-adopted definition of seroadaptive behaviors. To develop and refine the research CASI, research staff conducted four rounds of cognitive interviews with 16 MSM PHSKC STD clinic patients to ensure comprehension of each question. The research CASI asked men if their decision to form partnerships, use condoms, or adopt a sexual role was based on the HIV status of their partner. The preamble to the survey indicated that questions referred to behaviors adopted by the respondent to reduce his risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. All questions were stratified by partnership type (main versus casual) and partner HIV status. Examples of these questions for HIV-negative respondents include: In the past 12 months, did you ever top an HIV-positive casual partner instead of bottom him because he was HIV-positive? or In the past 12 months, did you ever decide not to use condoms with an HIV-negative casual partner because he was HIV-negative? In the research CASI, men were initially asked about ever engaging in behaviors (yes/no) and for men who indicated “yes”, they were asked about the frequency of engaging in each behavior (always/usually/sometimes/never). In both CASI’s, all questions were asked about behaviors in aggregate in the prior 12 months and did not query men on behaviors with specific partners. Respondent HIV status was self-reported. Men who reported that they did not know their HIV status were considered to be HIV-negative for the purposes of this analysis.

We compared clinical and research CASI responses for five sexual behaviors, defined in Table 1. Because the clinical CASI data did not ask men about behaviors separately for main and casual partners, we collapsed partnership type data from the research CASI to more accurately map to the clinical CASI data. We categorized all behaviors into binary categories, “always” versus “not always”, with “not always” including the responses usually, sometimes, and never. In addition to the behaviors outlined in Table 1, we additionally included the category of “no seroadaptive behavior” for the research CASI (i.e. men who did not report engaging in seroadaptive behaviors with HIV-discordant or unknown-status partners) to examine the HIV/STI risk among men who reported no seroadaptive behaviors.

HIV and STI Testing

HIV and STI testing conformed to routine clinical practice; no testing was done as part of this study. The clinic’s protocol is to recommend HIV testing (both rapid and laboratory) for MSM who have not previously tested HIV positive. Staff performed rapid tests using the INSTI test on whole blood (bioLytical Laboratories, Richmond, British Columbia) and our laboratory tested for HIV using a third-generation EIA (Genetic Systems HIV1/2 Plus O EIA, Biorad Laboratories, Redmond, Washington). MSM with a negative HIV EIA were tested using pooled HIV RNA testing [19–22]. Urethral specimens (swab or urine) were obtained from MSM with signs/symptoms of urethritis or who reported urethral exposure to a partner with gonorrhea (GC) or chlamydia (CT). Rectal specimens were obtained from MSM who reported receptive anal sex in the prior year. Urethral and rectal specimens were tested for GC and CT using nucleic acid amplification testing (APTIMA Combo 2, GenProbe Diagnostics, San Diego, CA). All MSM who agreed to have a blood sample obtained were tested for syphilis using the rapid plasma reagin test. A single, experienced disease investigational specialist reviews all cases of syphilis in King County and assigns a stage based on laboratory and clinical findings. We defined early syphilis as primary, secondary, or early latent infection.

Statistical Methods

Prevalence and Agreement of Seroadaptive Behaviors

The unit of analysis was the clinic visit and the study sample was limited to visits where men completed both the clinical and research CASI’s. We describe the baseline characteristics of the total analytic sample (Table 2) and present the prevalence of seroadaptive behaviors as reported in the clinical CASI (behavior definition) and research CASI (purposely-adopted definition), stratified by the HIV status of the respondent (Table 3). We used Cohen’s kappa statistic to measure agreement between the clinical and research CASI and classified the magnitude of agreement as slight (0.0–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80) and almost perfect (0.81–1.00) [23]. In addition, we report: [1] the proportion of visits where men reported purposely adopting a behavior (per the research CASI), among visits where men were classified as engaging in that behavior based on their sexual history (per the clinical CASI) (i.e. P(research | clinical); Table 3, Column D); and [2] the proportion of visits where we classified men as engaging in a behavior based on their sexual history (per the clinical CASI), among visits where men reported purposely adopting the behavior (per the research CASI) (i.e. P(clinical | research); Table 3, Column E). The first quantity defines how often men with a given behavior purposefully adopted that behavior as a risk reduction strategy. The second quantity describes how often men who reported adopting a seroadaptive behavior consistently completed or “executed” that behavior.

Purposely-Adopted Seroadaptive Behaviors and HIV/STI Test Positivity

For our second objective (to examine the risk of testing newly positive for HIV/STI by seroadaptive behavior), we calculated the proportion of visits where men tested newly positive for HIV or bacterial STI, among those who reported always engaging in a given behavior. We aggregated men who tested positive for urethral GC or CT and rectal GC or CT to examine urethral GC/CT test positivity and rectal GC/CT test positivity, respectively.

Results

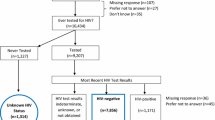

From February 2013 to June 2015, we enrolled participants at 3901 (55%) of 7143 visits by MSM patients, including 1997 unique HIV-negative MSM and 342 unique HIV-positive MSM. Ninety-six percent of visits (3751 of 3901) had behavioral data available from both the clinical and research CASI and are included in this analysis. Slightly more than one-half of visits were made by participants who were ≥30 years old, two-thirds of visits were by white, non-Hispanic MSM, and at >96% of visits men reported disclosing their HIV status or asking their partner’s HIV status in the prior year (Table 2). Nearly 90% of men reported ever using condoms with anal sex partners in the past year.

Prevalence and Agreement of Seroadaptive Behaviors

The prevalence and agreement of seroadaptive behaviors by method of definition is presented in Table 3. Regardless of the definition used, pure serosorting was overwhelmingly the most commonly reported behavior at visits by both HIV-negative and HIV-positive respondents. Consistent condom use was reported by 16–17% of HIV-negative respondents but only by <10% of HIV-positive respondents. The prevalence of other seroadaptive behaviors varied by behavior and definition but none were endorsed by more than 12% of respondents. The agreement of the two measures was highest for consistent condom use (substantial agreement for HIV-negative respondents and moderate agreement for HIV-positive respondents), pure serosorting (fair agreement), and condom serosorting (fair agreement) and lowest for seropositioning (slight agreement) and condom seropositioning (slight agreement).

The agreement we observed reflects both the purposeful adoption of reported sexual behaviors and the implementation of purposely adopted strategies. For example, among HIV-negative respondent-visits, of the 1375 visits where men reported that they only had sex with HIV-negative partners (i.e. pure serosorters per the behavioral definition), 1016 (73.9%) reported that they purposely chose to only have HIV-negative partners (i.e. pure serosorters per the purposely-adopted definition) (Table 3). Of the 1921 who reported that they chose to only have HIV-negative partners (i.e., pure serosorters per the purposely-adopted definition), only 52.9% (1016 of 1921) reported that they had only had sex with HIV-negative partners (i.e. pure serosorters per the behavioral definition). Relatively few men reported consistent condom use, seropositioning or condom seropositioning as a risk reduction strategy, and of those who did, less than half consistently adopted that behavior based on data from the clinical CASI. Consistent condom use was the exception to this pattern of discordance; 79.1% of men who always used condoms for anal sex reported that consistent condom use was a purposely-adopted risk reduction strategy, and 74% of men who reported consistent condom use was their strategy reported always using condoms.

Overall, HIV-positive men reported purposely adopted seroadaptive behaviors during fewer visits than HIV-negative men, with levels of pure serosorting and consistent condom use that were lower than those observed in HIV-negative men. As with HIV-negative men, many behaviors classified as seroadaptive based on the clinical CASI were not purposely adopted, and men reported behaviors consistent with their identified seroadaptive strategy during less than 60% of visits.

Purposely-Adopted Seroadaptive Behaviors and HIV/STI Test Positivity

Overall, men tested newly HIV positive at 38 (1.4%) of 2732 visits (Table 4). Among pure serosorters, HIV test positivity was 0.9%. For other behaviors, HIV test positivity ranged from a low of 0.0% for seropositioning to a high of 2.2% for men who did not engage in any seroadaptive behaviors.

Among all tested HIV-negative respondents, 22.5, 16.9 and 3.0% tested positive for rectal GC/CT, urethral GC/CT or early syphilis, respectively. Men who reported consistent condom use had the lowest rectal GC/CT (10.8%), urethral GC/CT (11.1%) and early syphilis (1.9%) test positivity. The rectal GC/CT test positivity was also relatively low (11.0%) for condom seropositioners (i.e. men who chose to use condoms for receptive anal sex with HIV-positive/unknown-status partners), while urethral GC/CT test positivity was highest (26.9%) for seropositioners (i.e. men who chose to adopt an insertive role with HIV-postive/unknown-status partners). Men who reported no seroadaptive behavior had the highest rectal GC/CT (27.0%) and syphilis (4.1%) test positivity. The risk of bacterial STI among serosorters, the largest group of HIV negative MSM, was not substantially lower than that observed in men who adopted no seroadaptive behavior.

STI test positivity was consistently higher for HIV-positive respondents than among HIV-negative respondents. Among HIV-positive respondents, seropositioners (i.e. men who chose to adopt a receptive anal sex role with HIV-negative/unknown-status partners) had the highest rectal GC/CT test positivity (40.0%). Condom seropositioners (i.e. men who used condoms for insertive anal sex with HIV-negative/unknown-status partners) had the lowest urethral GC/CT test positivity (13.3%).

Discussion

In this clinic-based population of MSM, we found that pure serosorting was the most commonly reported seroadaptive behavior, regardless of whether a behavioral definition or purposely-adopted definition was used. Overall, the prevalence of seroadaptive behaviors differed only slightly depending on the definition, but the agreement between the two measures was suboptimal and the concordance varied widely depending on the behavior. The relatively low level of agreement observed between our two approaches to measuring seroadaptive behaviors appeared to reflect a combination of low levels of success implementing purposely-adopted risk reduction strategies and the fact that some behaviors associated with diminished HIV risk were not purposely adopted. These findings suggest that the two methods to operationalize seroadaptive behaviors are distinct and thus the decision about which definition to employ should depend on the motivation for ascertaining behavioral information and the extent to which the different measures accurately identify risk. Of particular note, using our new survey which measured purposely-adopted seroadaptive behaviors, we found that men who reported no seroadaptive behavior had the highest HIV test positivity—twice as high as any other seroadaptive behavior—suggesting that adopting any seroadaptive behavior to reduce one’s risk of HIV is preferable to adopting no strategy.

The prevalence of pure serosorting that we observed using either definition is somewhat higher than previous estimates. Studies in North America that have employed a behavioral definition of pure serosorting have found that 8–31% of HIV-negative MSM and 12–21% of HIV-positive MSM engage in pure serosorting [1, 6, 15], while we noted a prevalence of 43 and 30%, respectively. The proportion of purposely-adopted pure serosorting in our study population (60% of visits by HIV-negative men and 34% visits by HIV-positive men), is slightly higher than two Swiss studies where 38–42% of men reported purposely-adopting pure serosorting [13, 14], The somewhat disparate findings between our study and others may be due to the different populations and time periods included in each study or different definitions used. Our behavioral definition did not require MSM to report CAI with seroconcordant partners, a stipulation of previous studies that would undoubtedly lower the prevalence of the behavior. Our purposely-adopted definition was also more inclusive in that we specifically asked men if they avoided serodiscordant or unknown-status partners. Employing this definition permitted us to assess how often men choose not to have partners based on the partner’s HIV status, instead of only examining how often men choose to have partners based on the partner’s HIV status. Despite differences in the prevalence of pure serosorting between our study and others, we found that the prevalence of the other seroadaptive behaviors was largely similar to studies that have employed behavioral [1, 6, 15] or purposely-adopted [13] definitions.

In our study population, pure serosorting and consistent condom use were not only the most commonly reported behaviors, but they were also the two behaviors that were most often purposely adopted. We found that 74% of HIV-negative and 52% of HIV-positive respondents who were classified as pure serosorters based on their behavior reported purposely adopting that behavior. For consistent condom use, the comparable proportions were 79 and 66%, respectively. These findings are similar to a partnership-level, Internet-based study of MSM [16], where the proportion of HIV-negative seroconcordant and HIV-positive seroconcordant partnerships that were purposely adopted (i.e. purposely adopted pure serosorting) was 80 and 48%, respectively. In a longitudinal study of San Francisco MSM [15], the seroadaptive strategy most adhered-to among HIV-negative MSM was pure serosorting (38% who intended to only have sex with men of concordant HIV status also reported that behavior at 12 months). Taken together, these studies suggest that, relative to other seroadaptive behaviors, pure serosorting is a very common, purposely-adopted strategy, though adherence to the strategy is inconsistent.

Agreement between the two definitions for behaviors other than pure serosorting and consistent condom use was poor and highly variable. The proportion of men who purposely adopted the sexual behavior they reported ranged from 11 (seropositioning) to 40% (condom serosorting) for HIV-negative MSM, and from 13 (condom seropositioning) to 54% (condom serosorting) for HIV-positive MSM. These data suggest a somewhat hierarchical classification of purposely adopted behaviors, with pure serosorting and consistent condom use reflecting behaviors that are most often adopted as conscious risk-reducing strategies whereas seropositioning and condom seropositioning are much less so. This hierarchy was also evident in participants’ reported success in executing seroadaptive behaviors. These were generally highest for pure serosorting and consistent condom use, particularly for HIV-negative men, and lowest for condom serosorting and condom seropositioning. It is somewhat unclear why we observed this pattern, but it is possible that partnership formation (e.g. serosorting) is more often based on partner HIV status while adopting an insertive or receptive role (e.g. seropositioning) is more likely to be influenced by partner-level factors other than HIV status [24–26] (i.e. preference for sexual role). It is also possible that men who practice pure serosorting do so out of fear of HIV infection as opposed to adopting a purposeful risk-reducing strategy [27].

Employing the purposely-adopted definitions from the new questionnaire, we found that HIV test positivity was 0.9% for men who adopted pure serosorting and was highest (2.2%) for men who reported no seroadaptive behavior. Though the absolute number of men who tested newly positive for HIV in our study population was small, these findings largely agree with studies employing a behavioral definition of seroadaptive behaviors [1], which have found that men who report no seroadaptive behavior not only have the highest HIV test positivity but also one that is approximately two-fold higher than pure serosorting. Our findings and others’ indicate that employing any seroadaptive behavior appears to lower one’s risk of HIV compared to employing no strategy at all, suggesting that behavioral risk messaging for HIV-negative MSM may consider encouraging men to adopt any strategy to reduce their risk of HIV, rather than focusing on recommending a specific behavior. The finding that having no seroadapative strategy is highly associated with HIV risk should prompt consideration of efforts to identify men without any purposeful plan for intervention (i.e. for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)).

We also found that bacterial STI test positivity varied by behavior, and that patterns in test positivity were different for HIV-negative and HIV-positive MSM. Notably, HIV-negative men who reported consistent condom use had the lowest STI test positivity but this was not the case for HIV-positive MSM. However, these results did serve to validate our new seroadaptive behavior questionnaire. For example, HIV-negative MSM who reported seropositioning (i.e. were the insertive partner with HIV-positive/unknown-status partners) had the highest urethral GC/CT positivity while HIV-positive MSM who were reported seropositioners (i.e. were the receptive partner with HIV-negative/unknown-status partners) had the highest rectal GC/CT test positivity. These findings advocate for the validity of these self-reported purposely-adopted behaviors and support the use of a tool measuring purposely adopted behaviors.

Though our study confirms that the two measures of seroadaptive behaviors are partially distinct from one another, the question remains—which measure of seroadaptive behaviors should be employed? From a clinical or HIV prevention perspective, the ultimate goal of measuring these behaviors is to better understand an individual’s risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. To the extent that past sexual behaviors align with future behaviors, using a sexual behavior history to measure seroadaptive behaviors may be preferred. In many clinical settings, patients’ sexual behavior history is already collected as part of routine clinical care. This information can be (and has been [4, 18]) used to construct behavioral definitions of seroadaptive behaviors, which has been invaluable to our understanding of the association of these behaviors with HIV and STI risk. On the other hand, it is possible that reported strategies may be better predictors of future HIV acquisition and thus might be more useful than the behavioral definition to identify individuals at high risk for HIV. Further, using a purposely-adopted definition may also be more appropriate to develop messaging that promotes these behaviors as harm-reduction strategies. Given that the HIV test positivity results using our new survey aligned closely with that of previous longitudinal studies employing a behavioral definition [1], the most important factor in deciding which measure to employ may simply be the specific goal or intent of measuring the behaviors (e.g. for behavioral surveillance, for clinical care, etc.). Ultimately, it is likely that a combination of the two methods (i.e. purposely adopted behaviors that were successfully executed) may be the most sensitive measure, and settings where both measures can be used should be encouraged to do so.

This study has a number of strengths. We used two independent CASI’s to capture behavioral and purposely-adopted definitions of seroadaptive behaviors, which allowed us to directly compare the two measures in the same population. Our definition of pure serosorting included partnership avoidance, a potential key seroadaptive strategy that has historically not been captured. Our research CASI was the result of considerable formative work to develop a series of seroadaptive strategy questions that could be consistently understood by our study population. There are also several limitations that merit discussion. First, although our data are helpful to describe the agreement between the two definitions of seroadaptive behaviors, the absence of a gold standard prohibits an assessment of the validity of the measures. Second, to the extent that individuals’ responses vary from one questionnaire to the next even with identical questions, our use of two independent CASI’s, though also a strength of this study, may have made the comparison of some behaviors unclear (i.e. the prevalence of purposely-adopted pure serosorting was higher than behaviorally-defined pure serosorting). Third, we collected aggregate data on types of partners as opposed to egocentric sexual network data (where men are asked specific questions about each sexual partner they have had in a specific time), an approach used in many prior studies. This does not allow us to understand how seroadaptive strategies may differ by partner. However, egocentric network data only collects information on partnerships that occur, thereby ignoring decisions not to form partnerships (i.e. partnership avoidance), an important seroadaptive strategy that was incorporated into our research CASI definition of pure serosorting. Also, insofar as our goal is to develop questions that can be used in clinical practice, aggregate data is simpler and likely much easier to incorporate into clinical or prevention counseling routines. Fourth, we did not collect information from participants about their motivations for employing seroadaptive behaviors or their understanding of these behaviors as risk-reducing strategies. Future studies on this topic should employ qualitative methods to elucidate this information to inform seroadaptive behavior measurement tools. Fifth, we categorized behaviors as “always” versus “not always” and collapsed data on primary and casual partners from the research CASI. Given that seroadaptive strategies may differ by partnership type [28], it is unclear how this may have affected the agreement between the two measures. Sixth, data on sexual behavior are subject to recall bias since participants were asked about their sexual behaviors in the past 12 months. However, the same recall period was used for both CASI’s so although this may have affected the prevalence estimates, it likely did not affect the agreement. Seventh, the kappa statistic is sensitive to the prevalence of behaviors and may be artificially low for less commonly reported behaviors. Some behaviors were quite uncommon in our study population, perhaps influencing the kappa values we report. Eighth, the absolute number of men who tested newly HIV positive was small and thus estimates of the proportion of men testing newly HIV positivity by behavior was often only based on one or two events. Finally, this was a clinic-based, frequently HIV-tested population of predominately white MSM where HIV status disclosure was high. How the two methods of measurement would compare in other racially- and geographically-diverse populations is unclear.

In summary, we found that the two measures of seroadaptive behaviors—a behavioral definition and purposely-adopted definition—are distinct from one another, a distinction that may have important public health implications. The complexities in measuring seroadaptive behaviors have made it difficult to craft clear and simple public health messages about the practice, and as a result, we do not know which behaviors, if any, should be promoted and to whom. Behavioral definitions of serosorting, though useful, may not accurately measure seroadaptive behaviors as active risk-reduction strategies, and thus using this definition to inform the development of harm-reduction messaging is questionable. Ultimately, the preferred measure, particularly in the era of PrEP, is likely one that better predicts an individual’s risk of acquiring HIV. To that end, future prospective studies are needed to better define the most clinically meaningful approach to measuring seroadaptive behaviors. In the absence of such data, we believe that clinicians and others counseling MSM about HIV risk reduction should integrate information about their self-reported behavior with information on what actions individuals are explicitly taking to diminish their risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV.

References

Vallabhaneni S, Li X, Vittinghoff E, Donnell D, Pilcher CD, Buchbinder SP. Seroadaptive practices: association with HIV acquisition among HIV-negative men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e45718.

Velter A, Bouyssou-Michel A, Arnaud A, Semaille C. Do men who have sex with men use serosorting with casual partners in France? Results of a nationwide survey (ANRS-EN17-Presse Gay 2004). Euro Surveill. 2009;14(47):429–33.

Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Johnson TP, Pollack LM. Sexual risk behavior and drug use in two Chicago samples of men who have sex with men: 1997 vs. 2002. J urban health. 2010;87(3):452–66.

Golden MR, Stekler J, Hughes JP, Wood RW. HIV serosorting in men who have sex with men: is it safe? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(2):212–8.

Snowden JM, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Seroadaptive behaviours among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: the situation in 2008. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(2):162–4.

Snowden JM, Wei C, McFarland W, Raymond HF. Prevalence, correlates and trends in seroadaptive behaviours among men who have sex with men from serial cross-sectional surveillance in San Francisco, 2004–2011. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(6):498–504.

Jin F, Prestage GP, Templeton DJ, Poynten IM, Donovan B, Zablotska I, et al. The impact of HIV seroadaptive behaviors on sexually transmissible infections in HIV-negative homosexual men in Sydney Australia. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(3):191–4.

Holt M, Lea T, Mao L, Zablotska I, Lee E, de Wit JB, et al. Adapting behavioural surveillance to antiretroviral-based HIV prevention: reviewing and anticipating trends in the Australian Gay community periodic surveys. Sex Health. 2006. doi:10.1071/SH16072.

Philip SS, Yu X, Donnell D, Vittinghoff E, Buchbinder S. Serosorting is associated with a decreased risk of HIV seroconversion in the EXPLORE Study Cohort. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12662.

Jin F, Crawford J, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, Imrie J, Kippax SC, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. AIDS. 2009;23(2):243–52.

Khosropour CM, Dombrowski JC, Swanson F, Kerani RP, Katz DA, Barbee LA, et al. Trends in Serosorting and the Association With HIV/STI Risk Over Time Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(2):189–97.

World Health Organization. Evidence and Technical Recommendations: Serosorting. Geneva: Switzerland; 2011.

Dubois-Arber F, Jeannin A, Lociciro S, Balthasar H. Risk reduction practices in men who have sex with men in Switzerland: serosorting, strategic positioning, and withdrawal before ejaculation. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(5):1263–72.

Lociciro S, Jeannin A, Dubois-Arber F. Men having sex with men serosorting with casual partners: who, how much, and what risk factors in Switzerland, 2007–2009. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):839.

McFarland W, Chen YH, Nguyen B, Grasso M, Levine D, Stall R, et al. Behavior, intention or chance? A longitudinal study of HIV seroadaptive behaviors, abstinence and condom use. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):121–31.

Siegler AJ, Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM, Rosenberg ES. The role of intent in serosorting behaviors among men who have sex with men sexual partnerships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(3):307–14.

Khosropour CM, Dombrowski JC, Hughes JP, Manhart LE, Golden MR. Evaluation of a computer-based recruitment system to enroll men who have sex with men (MSM) into an observational HIV behavioral risk study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(6):477–83.

Golden MR, Dombrowski JC, Kerani RP, Stekler JD. Failure of serosorting to protect African American men who have sex with men from HIV infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(9):659–64.

Stekler J, Maenza J, Stevens CE, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Wood RW, et al. Screening for acute HIV infection: lessons learned. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(3):459–61.

Stekler J, Swenson PD, Wood RW, Handsfield HH, Golden MR. Targeted screening for primary HIV infection through pooled HIV-RNA testing in men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2005;19(12):1323–5.

Stekler JD, Baldwin HD, Louella MW, Katz DA, Golden MR. ru2hot?: a public health education campaign for men who have sex with men to increase awareness of symptoms of acute HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(5):409–14.

Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Dragavon J, Thomas KK, Brennan CA, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(3):444–53.

Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Ostergren JE, Rosser BR, Horvath KJ. Reasons for non-use of condoms among men who have sex with men: a comparison of receptive and insertive role in sex and online and offline meeting venue. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(2):123–40.

Prestage G, Brown G, Down IA, Jin F, Hurley M. “It’s hard to know what is a risky or not a risky decision”: gay men’s beliefs about risk during sex. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1352–61.

Ronn M, White PJ, Hughes G, Ward H. Developing a conceptual framework of seroadaptive behaviors in HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men. J Infect Dis. 2014;1(210 Suppl 2):S586–93.

Prestage G, Down IA, Bradley J, McCann PD, Brown G, Jin F, et al. Is optimism enough? Gay men’s beliefs about HIV and their perspectives on risk and pleasure. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(3):167–72.

Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Cain DN, Cherry C, Stearns HL, Amaral CM, et al. Serosorting sexual partners and risk for HIV among men who have sex with men. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6):479–85.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the men who participated in this study and the front desk staff and clinic staff at the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD clinic. We also thank Shirley Zhang for survey programming support and data management support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R21 AI098497; Grant T32 AI07140 trainee support to CMK; and grants K23MH090923 and L30 MH095060 to JCD); and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (Grant P30 AI027757) which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute on Aging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MRG has conducted studies unrelated to this work funded by grants from Cempra and Melinta. JCD has conducted studies unrelated to this work funded by grants to the University of Washington from ELITech, Melinta Therapeutics, and Genentech. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khosropour, C.M., Dombrowski, J.C., Hughes, J.P. et al. Operationalizing the Measurement of Seroadaptive Behaviors: A Comparison of Reported Sexual Behaviors and Purposely-Adopted Behaviors Among Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) in Seattle. AIDS Behav 21, 2935–2944 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1682-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1682-0