Abstract

We examined individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors associated with condom use during receptive anal intercourse (RAI) among 163 low-income, racially/ethnically diverse, HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in Los Angeles (2007–2010). At baseline, 3-month, and 12-month visits, computer-assisted self-interviews collected information on ≤3 recent male partners and the last sexual event with those partners. Factors associated with condom use during RAI at the last sexual event were identified using logistic generalized linear mixed models. Condom use during RAI was negatively associated with reporting ≥ high school education (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.32, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 0.11–0.96) and methamphetamine use, specifically during RAI events with non-main partners (AOR = 0.20, 95 % CI 0.07–0.53) and those that included lubricant use (AOR = 0.20, 95 % CI 0.08–0.53). Condom use during RAI varies according to individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors that should be considered in the development of risk reduction strategies for this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV in the United States (US), and accounted for 68 % of HIV infections diagnosed among adults and adolescents in 2013 [1]. Among MSM there are substantial disparities in the prevalence and incidence of HIV by race/ethnicity. It has been estimated that the rates of HIV diagnosis among African American MSM and Hispanic/Latino MSM are 6.0 and 2.7 times that among White MSM, respectively [2]. One factor driving these disparities may be the well documented socio-economic inequities across racial/ethnic groups in the US, such as lower levels of income and elevated rates of poverty [3], which have been associated with a higher prevalence of HIV among MSM [4, 5]. As one strategy to curb the HIV epidemic among MSM in the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that MSM “at substantial risk of HIV acquisition” consider the use of daily oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [6], which significantly reduces the risk of HIV infection [7–12]. However, because consistent daily use of PrEP is required for maximal protection against HIV and PrEP does not protect against other sexually transmitted infections, behavioral interventions designed to support consistent condom use during anal intercourse remain crucial to HIV prevention among MSM [13].

Recognizing that sexual risk behaviors vary within-individuals and depend on multiple contextual or situational factors [14, 15], numerous sexual event-specific analyses have examined the influence of event-level factors on condom use during anal intercourse among MSM and have provided information critical to the development of MSM-specific HIV prevention interventions that promote consistent condom use [16–29]. Although an in-depth review of the literature is beyond the scope of this article, previous event-specific analyses have identified an association between condom-unprotected anal intercourse (CUAI) and substance use before or during sex [16, 17, 19, 23, 26] (specifically methamphetamine use [20–22, 29]), partner’s substance use before or during sex [17, 23, 24], sex with a main or steady partner [25, 27, 28], knowledge of partner’s HIV status [16, 18], and sex with a seroconcordant partner [25, 29]. However, there were several notable differences across these studies. For example, definitions of CUAI were not consistent as some studies examined CUAI generally [18, 22, 24, 25], while others stratified CUAI by position (i.e., insertive anal intercourse [IAI] vs. receptive anal intercourse [RAI]) [16, 20, 27–29], partnership serostatus (i.e., seroconcordant vs. serodiscordant) [17], and partner type (i.e., main vs. casual) [16, 18] or restricted their analysis to casual partners only [19, 21, 23, 26]. Many of these studies also focused event-specific analyses on the effect of substance use before or during sex on CUAI [16, 19–22]. Those that examined the relationship between CUAI and a broader range of event-level factors (e.g., sexual/emotional attraction to partner, knowledge of partner’s sexual history, location of sexual event, lubricant use during sexual event, ejaculation during sexual event, duration of penetration) were conducted among Latino [24, 25], HIV-positive [23], or predominately White, high-income, and educated MSM [17, 26–28] and did not consistently control for partnership serostatus or substance use before or during sex [27, 28]. Thus, given the elevated rates of HIV among low-income, racial/ethnic minority MSM in the US [2, 4, 5, 30], additional event-specific analyses that examine the relationship between condom use and a range of sexual event-level factors among low-income, racially/ethnically diverse MSM are needed to expand our understanding of sexual risk behaviors and help focus risk reduction strategies for those most vulnerable to HIV.

Because condom-unprotected RAI is associated with the greatest risk of HIV infection [31–33], we used longitudinal data from a cohort of high-risk, low-income, racially/ethnically diverse HIV-negative MSM to simultaneously examine the effect of multiple individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors on condom use during RAI at the last sexual event with recent sexual partners. More specifically, we examined whether sexual event-level factors associated with condom use in previous research are similarly associated with condom use among these MSM. We hypothesized that sex with a main partner, sex with a seroconcordant partner, and substance use, particularly methamphetamine use, before or during sex would be inversely associated with condom use during RAI.

Methods

Study Design

In the Pipeline—Enrollment in a Research Registry for Microbicide Clinical Trials—was conducted in Los Angeles between 2007 and 2010 among 422 MSM who practice RAI by the Network for AIDS Research in Los Angeles (NARLA), a consortium of infectious disease doctors, epidemiologists, sociologists, psychologists, and behavioral scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Friends Research Institute, Inc. (FRI), California State University, Dominguez Hills, and AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA). In the Pipeline was designed to examine barriers to microbicide trial participation among MSM and identify the best format for the delivery of educational materials on rectal microbicides. Racially/ethnically diverse MSM were recruited for the study via flyers and advertisements posted online and at three community-based service organizations in Los Angeles: the UCLA Clinical AIDS Research and Education (CARE) Center, Friends Community Center (the Los Angeles site of FRI), and APLA. To be eligible for participation, interested individuals had to be at least 18 years-old, anatomically male, willing to test for HIV/STIs, self-report RAI in the past 12 months, and provide informed consent. By design, approximately 50 % of In the Pipeline participants were HIV-positive. HIV-positive participants were mostly (>90 %) recruited from the UCLA CARE Center or APLA, which provide services to HIV-infected individuals, while two-thirds of HIV-negative participants were recruited from the Friends Community Center, which primarily serves low-income, substance-using MSM and transgender women. All eligible participants underwent rapid HIV testing, unless self-reported HIV infection could be confirmed via medical records maintained at the UCLA CARE Center or APLA. Positive rapid HIV test results were confirmed via Western Blot. Given our goal to inform the development of HIV prevention strategies for HIV-negative MSM, we restricted our analysis to HIV-negative In the Pipeline participants.

Study Procedures

In the Pipeline participants were followed for 1 year, and completed three study visits (at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months) conducted by trained study staff at the UCLA CARE Center, Friends Community Center, and APLA. During each visit, participants completed computer-assisted self-interviews (CASIs), which collected information on socio-demographics, substance use, and sexual behaviors. Participants were compensated up to $105 for completing all three study visits. Human Subjects Protection Committees at UCLA, FRI, and APLA approved all study procedures.

Measures

Individual-Level Factors

At baseline, CASIs collected information on socio-demographics and substance use in the past 6 months. Socio-demographics included: age (in years), race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Native American, Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, mixed race or other) sexual identity (gay/homosexual, bisexual, or straight/heterosexual), highest level of education (no formal schooling, less than high school, high school graduate, some college or university, college or university graduate, or graduate or professional degree), annual income (≤$9800, $9801–$19,600, $19,601–$29,400, >$29,400), employment (full-time employment, part-time employment, full-time student, disabled and not able to work, retired, or unemployed), and homelessness in the past year. Substance use questions ascertained information on the types of substances used in the past 6 months (alcohol, marijuana, crack or powder cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, or opioids), as well as their frequency of use (once or twice, monthly, weekly, or daily/almost daily). Data on sexual activity in the past month (number of male anal intercourse partners and number of RAI events) were also collected at each visit.

Partnership-Level Factors

At each visit, CASIs collected partner-specific data on up to three recent sexual partners (i.e., last partner [P1], second to last partner [P2], and third to last partner [P3]). Age (in years), race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Native American, Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or other), HIV status (HIV-negative, HIV-positive, or HIV status unknown), and partner type were collected for each partner. In our analysis, HIV-positive and HIV status unknown partners were considered serodiscordant. Main partners were defined as the participant’s primary or most important sexual partner, while regular partners (someone the participant had sex with on a regular basis, but did not consider a main partner), friends, acquaintances, one-time partners, unknown individuals, or trade partners were considered non-main partners. For participants’ most recent partners (P1), participants were asked about perceived partner concurrency (How many other people do you think P1 had anal or vaginal sex with during the same time period you were sexual partners?), trade sex within the partnership (Did you ever give P1 drugs, money or other goods to have anal sex with you? and Did P1 ever give you drugs, money or other goods to have anal sex with you?), and partnership intimacy. Intimacy was measured via the 27-item Partnership Assessment Scale designed to ascertain the amount of information known about and activities engaged in with sexual partners (Cronbach’s α: visit 1 = 0.95; visit 2 = 0.91; visit 3 = 0.94) [34]. CASIs also included a partner tracking system to identify partnerships continuing at subsequent visits.

Sexual Event-Level Factors

For the last sexual event with each partner, participants were asked whether any substances were used (marijuana, methamphetamine, ecstasy, volatile nitrites [poppers], crack or powder cocaine, ketamine, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid [GHB], heroin, acid, mushrooms, oxycontin, Vicodin, Valium, and Viagra) and whether they had RAI. If a participant reported having RAI, he was also asked about lubricant and condom use during RAI, as well as whether his partner ejaculated inside of him. Additional information on the location (participant’s home, partner’s home, someone else’s home, hotel or motel, work/school, church, car, recreational area [e.g., movies, bowling alley, sporting event, etc.], public space [e.g., park or public restroom], bathhouse or sauna, dance club or bar, sex club, jail or prison, abandoned building, crack house, or other) and duration (in minutes) of RAI was collected for the last sexual event with most recent partners only (P1). Given that In the Pipeline was designed to inform future research on rectal microbicides, which will most likely be applied by the receptive partner prior to or during anal intercourse, data on IAI were not collected.

Statistical Analysis

To identify individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors associated with condom use during RAI at the last sexual event with reported partners, we modeled condom use during RAI using logistic generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with individual random effects to account for the correlation between sexual events with different partners nested within the same individual. Although some of the reported partnerships continued over time, there was not enough information in the data to fit a model with partnership random effects. Thus, we restricted our analysis to the first observation for continuing partnerships. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were examined for each individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factor. Factors were selected for inclusion in our final adjusted model based on previous research indicating their association with sexual risk behaviors or HIV infection risk among MSM (Model 1). Analyses considering factors only collected for participants’ most recent partners (P1) were limited to the sexual events for which they were collected, and for consistency adjusted estimates for these factors were only adjusted for other factors collected for all reported partners. Finally, in exploratory analyses, we assessed the significance (α level = 0.05) of two-way interactions (one at a time) between partnership-level and sexual event-level factors collected for all reported partners, including partner type (main or non-main), age mixing (partner >10 years younger than participant, participant and partner within 10 years of age, or partner >10 years older than participant), partnership serostatus (seroconcordant or serodiscordant), methamphetamine use, volatile nitrite (popper) use, crack or powder cocaine use, Viagra use, lubricant use, and ejaculation (Models 2 and 3 include significant two-way interactions). All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC).

Sample Selection

Given our focus on condom use during RAI among HIV-negative MSM, we excluded two HIV-negative anatomically male transgender women In the Pipeline participants from our analysis sample. Of the 208 HIV-negative MSM participants, 163 provided data on condom use during RAI at the last sexual event with at least one partner and were included in our analysis. Compared to those who provided data on condom use during RAI at the last sexual event with at least one partner (n = 163), those who did not (n = 45) reported fewer male anal intercourse partners and fewer RAI events in the past month at baseline and were more likely to be African American, identify as straight or heterosexual, or report homelessness in the past year.

Results

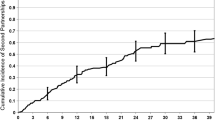

Participants (N = 163) contributed data from a median of two visits to the analysis (IQR = 1–2). Participants were racially/ethnically diverse (38 % White; 24 % African American; 27 % Hispanic/Latino), mostly identified as gay or homosexual (58 %), and had a mean age of 35.8 years (SD = 11.0; min = 18.0; max = 72.0) (Table 1). Although 87 % of participants reported at least a high school education, 37 % reported being unemployed and almost half reported an annual income less than $9800 or homelessness in the past year. Substance use (past 6 months) was common with 59 % of participants reporting any substance use (crack or powder cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens or opioids), 40 % reporting crack or powder cocaine use, and 34 % reporting methamphetamine use.

At baseline, 42 % of participants provided outcome data on condom use during RAI at the last sexual event with one partner only, 18 % provided these data for two partners, and 42 % provided these data for three partners. On average those who provided outcome data for fewer partners reported fewer RAI events in the past month and were more likely to be African American, not identify as gay or homosexual, report an annual income less than $9800, or report homelessness in the past year (data not shown).

During the study period, participants provided data on condom use during 404 RAI events (Table 2). Of these RAI events, 23 % were with main partners and 65 % were with partners within 10 years of age. Over half of RAI events were with HIV seroconcordant partners (58 %; 229/392). However, of RAI events with serodiscordant partners (n = 163), 93 % were with serostatus unknown partners and only 7 % were with HIV-positive partners. Participants reported any substance use (methamphetamine, ecstasy, volatile nitrites [poppers], crack or powder cocaine, ketamine, GHB, heroin, acid, mushrooms, oxycontin, Vicodin, Valium, or Viagra) during 37 % of RAI events, and methamphetamine use during 18 % of RAI events.

Condoms were used during 56 % of RAI events. Table 3 displays individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors associated with condom use during these RAI events. In unadjusted analyses, self-identifying as gay or homosexual (OR = 1.83; 95 % CI 1.05, 3.21) and lubricant use during RAI (OR = 4.06; 95 % CI 2.39, 6.90) were associated with condom use during RAI, while sex with a main partner (OR = 0.56; 95 % CI 0.32, 0.95) and methamphetamine use (OR = 0.50, 95 % CI 0.27, 0.93) were associated with not using condoms during RAI. After adjusting for individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors (Model 1), reporting at least a high school education (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.32, 95 % CI 0.11, 0.96) and methamphetamine use (AOR = 0.28, 95 % CI 0.12, 0.69) were associated with not using condoms during RAI, while lubricant use during RAI was associated with condom use during RAI (AOR = 6.41, 95 % CI 3.21, 12.80).

Although there was no overall association between sex with a main partner and condom use during RAI after adjusting for individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors (Model 1), we found that the effect of methamphetamine use on condom use during RAI was modified by partner type (Model 2; partner type by methamphetamine use interaction: F statistic = 3.46; p value = 0.06). Methamphetamine use was associated with not using condoms during RAI with non-main partners (OR = 0.20, 95 % CI 0.07, 0.53), but was not associated with condom use during RAI with main partners (AOR = 1.17, 95 % CI 0.21, 6.57). We also found that the effect of methamphetamine use on condom use during RAI was modified by lubricant use during RAI (Model 3; lubricant use by methamphetamine use interaction: F statistic = 4.08; p value = 0.04). Methamphetamine use was associated with not using condoms during RAI events that included lubricant use (AOR = 0.20, 95 % CI 0.08, 0.53), but was not associated with condom use during RAI events that excluded lubricant use (OR = 1.47, 95 % CI 0.26, 8.41).

Discussion

We examined the effect of individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors on condom use during RAI among low-income, racially/ethnically diverse HIV-negative MSM in Los Angeles. As seen in similar sexual event-specific analyses conducted among MSM populations with different socio-demographic profiles [17, 23–28], condom use during RAI varied across sexual events according to several event-level factors. While there were similarities between our findings and those from previous sexual event-specific analyses in terms of event-level factors associated with condom use during RAI (i.e., methamphetamine use before or during sex) [20–22, 29], several event-level factors associated with condom use in previous research were not associated with condom use in our sample (i.e., partner type and partnership serostatus) [25, 27–29]. Moreover, we observed an association between lubricant use and condom use during RAI, which has not been documented in previous research [28]. Given these differences, our findings underscore the continued need to understand the impact of event-level factors on sexual risk behaviors across socio-demographically diverse MSM populations. Moreover, our findings provide critical information for the development of targeted condom promotion and HIV risk reduction strategies for low-income, racially/ethnically diverse MSM who are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection in the US.

Consistent with previous sexual-event specific analyses [20–22, 29], we observed an overall relationship between methamphetamine use and condom use during RAI, such that condom use was less frequent in the context of methamphetamine use. However, we also found that the relationship between methamphetamine use and condom use during RAI differed by partner type. While methamphetamine use was not associated with condom use in the context of main partnerships, it was inversely associated with condom use during RAI in the context of non-main partnerships. In an earlier event-specific analysis conducted among racially/ethnically diverse, young MSM in urban areas across the US, a similar relationship was observed between being high on alcohol or drugs and engaging in condom-unprotected RAI with casual partners that did not remain in the context of sex with main partners [16]. Over repeated sexual encounters, main partnerships likely establish norms surrounding condom use. Thus, without established norms to rely on, non-main partnerships may be more susceptible to the dis-inhibitory effects of methamphetamine [35, 36] and practice higher risk sexual behaviors in the context of methamphetamine use. HIV prevention strategies that facilitate risk reduction planning with non-main partners may help reduce the risk of HIV acquisition among methamphetamine using MSM. Although consistent condom use remains an essential HIV prevention strategy even in the context of PrEP [13], daily oral PrEP, which does not rely on event-specific adherence, may be a more feasible risk reduction strategy for methamphetamine using MSM with non-main partners. Available data do not support concerns that biomedical HIV prevention strategies, such as PrEP, cannot be successfully implemented with people who use drugs [37, 38].

Unlike a previous sexual event-specific analysis conducted among mostly White, highly educated HIV-negative MSM recruited via social-networking websites for MSM in the US [28], we observed an overall association between lubricant use and condom use during RAI. However, we also found that lubricant use during RAI modifies the relationship between methamphetamine use and condom use. That is, methamphetamine use was inversely associated with condom use during RAI in the context of lubricant use, but was not associated with condom use during RAI in the absence of lubricant use. We previously reported on an event-specific analysis of factors associated with lubricant use during RAI within this sample where we found that substance use was associated with lubricant use within partnerships that did not use condoms during RAI [39]. As we previously hypothesized [39], the lack of condom use during RAI may have been driven by a desire to enhance sexual pleasure, which some MSM have reported is reduced in the context of condom use [40, 41]. Given that methamphetamine use decreases the sensation of pain during RAI [35] and is often motivated by a desire to enhance sexual pleasure [42], methamphetamine use in the context of lubricant use, which reduces friction during AI and thus also enhances sexual pleasure, may be associated with less condom use so as not to interfere with sexual pleasure. While additional research is needed to confirm and understand the mechanism underlying this finding, alternative prevention strategies that do not limit sexual pleasure, such as rectal microbicides [43], may be more acceptable to HIV-negative MSM who use methamphetamine to enhance their sexual experiences.

Despite previous research demonstrating that MSM use condoms less frequently with main partners [25, 27, 28], we did not observe an overall association between partner type and condom use. Decreased condom use in the context of main partnerships has been attributed to the belief that engaging in CUAI is a symbol of trust within partnerships and that condom use interferes with intimacy [44–46], suggesting that partnership dynamics related to condom use within low-income MSM populations may differ from those within general MSM populations. While this finding requires further investigation, it also underscores the need to better understand the impact of partnership dynamics on HIV transmission risk across diverse MSM populations.

Although the HIV status of one’s sexual partner is a major determinant of risk, unlike findings from previous sexual event-specific analyses [25, 29], condom use during RAI with serodiscordant (HIV-positive or HIV status unknown) partners was not more common than with seroconcordant partners within our sample. Seroadaptation refers to the practice of sexual risk behaviors based on the perceived HIV status of one’s sexual partners [47, 48], and has been documented as a widely used risk reduction strategy among MSM [49, 50], including low-income MSM [29]. Thus, the absence of an association between partnership serostatus and condom use during RAI within our sample may partially be explained by the fact that only 7 % of serodiscordant partnerships were with known HIV-positive partners. Nevertheless, participants could have been exposed to HIV during sexual events with HIV status unknown partners, suggesting a continued need for interventions that encourage or facilitate HIV serostatus disclosure between sexual partners to support consistent condom use in the context of risk.

Finally, we found that participants with at least a high school education were less likely to use condoms during RAI, which is inconsistent with previous research documenting a relationship between lower levels of education and the practice of higher risk sexual behaviors among MSM [17, 21]. While this finding warrants further investigation, it may be explained by the fact that those with less education were more likely to report ever exchanging sex for drugs, money or other goods with their most recent sexual partners (although this association was not statistically significant), which may be due to the fact that they were also more likely to report an annual income less than $9800. Thus, condom use during RAI may have been more frequent in the context of these potentially higher risk partnerships.

Our study has several limitations. First, In the Pipeline participants may not be representative of all RAI practicing MSM as they were largely recruited from the Friends Community Center, which primarily serves low-income, substance using MSM and transgender women. Additionally, event-specific data were only collected for the last event with up to three recent sexual partners at each visit and we further restricted our analysis to events in which the participant provided data on condom use during RAI. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to all RAI events among MSM. Second, due to the sensitive nature of information on substance use and sexual practices, participants may have under-reported these behaviors. However, In the Pipeline utilized CASIs, which have been shown to minimize under-reporting of sensitive information relative to data collection via face-to-face interviews [51, 52]. Third, we cannot be certain of the accuracy of reported partner characteristics as partners were not directly interviewed. Finally, methamphetamine use may not have been associated with condom use during RAI in the context of main partnerships or in the absence of lubricant use because few RAI events were with main partners (23 %) or excluded lubricant use (30 %).

Despite these limitations, some major strengths of our study are its focus on RAI events reported by high-risk, low-income, racially/ethnically diverse MSM and use of detailed event-level data. Our findings provide new insight on the potential impact of individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors on sexual risk among MSM, and have implications for future research exploring the role of contextual factors on condom use during RAI within this population. More specifically, additional research is needed to understand the mechanism underlying our findings related to education and lubricant use, as well as event-level factors associated with condom use during RAI events with serodiscordant partners. Finally, research examining whether the individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level factors associated with condom use during RAI within our sample are similarly associated with condom use within MSM racial/ethnic groups is needed to advance HIV prevention science and help focus the development of interventions promoting condom use and other HIV prevention strategies for MSM at greatest risk of HIV infection.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/2013/surveillance_Report_vol_25.html (2015). Accessed 8 Mar 2015.

Purcell DW, Johnson CH, Lansky A, et al. Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:98–107.

U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Reports, P60-249, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2013. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-249.pdf (2014). Accessed 18 Apr 2015.

Robertson MJ, Clark RA, Charlebois ED, et al. HIV seroprevalence among homeless and marginally housed adults in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1207–17.

Xia Q, Osmond DH, Tholandi M, et al. HIV prevalence and sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men: results from a statewide population-based survey in California. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(2):238–45.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Public Health Service Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2014 Clincal Practice Guideline. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf (2014). Accessed 7 Jan 2015.

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99.

Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410.

Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34.

Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90.

McCormack S, Dunn D. Pragmatic open-label randomised trial of preexposure prophylaxis: the PROUD study [22LB]. Presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2015; Seattle, WA.

Baeten J, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L et al. Near elimination of HIV transmission in a demonstration project of PrEP and ART [24]. Presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistics Intefctions; 2015; Seattle, WA.

Mansergh G, Koblin BA, Sullivan PS. Challenges for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in the United States. PLoS Med. 2012;9(8):e1001286.

Cooper ML. Toward a person x situation model of sexual risk-taking behaviors: illuminating the conditional effects of traits across sexual situations and relationship contexts. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(2):319–41.

Braine N, van Sluytman L, Acker C, Friedman S. Des Jarlais DC. Sexual contexts and the process of risk reduction. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(7):797–814.

Stueve A, O’Donnell L, Duran R, San Doval A, Geier J. Being high and taking sexual risks: findings from a multisite survey of urban young men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(6):482–95.

Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(10):1002–12.

Prestage G, Van de Ven P, Mao L, Grulich A, Kippax S, Kaldor J. Contexts for last occasions of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-negative gay men in Sydney: the health in men cohort. AIDS Care. 2005;17(1):23–32.

Holtgrave DR, Crosby R, Shouse RL. Correlates of unprotected anal sex with casual partners: a study of gay men living in the southern United States. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):575–8.

Mansergh G, Shouse RL, Marks G, et al. Methamphetamine and sildenafil (Viagra) use are linked to unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex, respectively, in a sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(2):131–4.

Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Humberstone M, Wong T, Wolitski RJ. A comparison of on-line and off-line sexual risk in men who have sex with men: an event-based on-line survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(2):235–43.

Koblin BA, Murrill C, Camacho M, et al. Amphetamine use and sexual risk among men who have sex with men: results from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance study–New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42(10):1613–28.

Wilson PA, Cook S, McGaskey J, Rowe M, Dennis N. Situational predictors of sexual risk episodes among men with HIV who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(6):506–8.

Wilson PA, Diaz RM, Yoshikawa H, Shrout PE. Drug use, interpersonal attraction, and communication: situational factors as predictors of episodes of unprotected anal intercourse among Latino gay men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):691–9.

Zea MC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT. Unprotected anal intercourse among immigrant Latino MSM: the role of characteristics of the person and the sexual encounter. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):700–15.

Lambert G, Cox J, Hottes TS, et al. Correlates of unprotected anal sex at last sexual episode: analysis from a surveillance study of men who have sex with men in Montreal. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):584–95.

Rosenberger JG, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Condom use during most recent anal intercourse event among a U.S. sample of men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. 2012;9(4):1037–47.

Hensel DJ, Rosenberger JG, Novak DS, Reece M. Sexual event-level characteristics of condom use during anal intercourse among HIV-negative men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(7):550–5.

Murphy RD, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Hucks-Ortiz C, Shoptaw SJ. Seroadaptation in a sample of very poor Los Angeles area men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1862–72.

Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e17502.

Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(4):1048–63.

Grulich AE, Zablotska I. Commentary: probability of HIV transmission through anal intercourse. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(4):1064–5.

Jin F, Jansson J, Law M, et al. Per-contact probability of HIV transmission in homosexual men in Sydney in the era of HAART. AIDS. 2010;24(6):907–13.

Gorbach PM, Holmes KK. Sexual partnership effects on STIs/HIV transmission. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2008. p. 127–36.

Drumright LN, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Club drugs as causal risk factors for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men: a review. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10–12):1551–601.

Colfax G, Santos GM, Chu P, et al. Amphetamine-group substances and HIV. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):458–74.

Landovitz RJ, Fletcher JB, Inzhakova G, Lake JE, Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. A novel combination HIV prevention strategy: post-exposure prophylaxis with contingency management for substance abuse treatment among methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(6):320–8.

Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–9.

Pines HA, Gorbach PM, Reback CJ, Landovitz RJ, Mutchler MG, Mitsuyasu R. Commercial lubricant use among HIV-negative men who have sex with men in Los Angeles: implications for the development of rectal microbicides for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1609–18.

Carballo-Dieguez A, Bauermeister J. “Barebacking”: intentional condomless anal sex in HIV-risk contexts. Reasons for and against it. J Homosex. 2004;47(1):1–16.

Calabrese SK, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT. The pleasure principle: the effect of perceived pleasure loss associated with condoms on unprotected anal intercourse among immigrant Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(7):430–5.

Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Motivations associated with methamphetamine use among HIV+ men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(3):149–56.

Carballo-Dieguez A, Ventuneac A, Dowsett GW, et al. Sexual pleasure and intimacy among men who engage in “bareback sex”. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S57–65.

Remien RH, Carballo-Dieguez A, Wagner G. Intimacy and sexual risk behaviour in serodiscordant male couples. AIDS Care. 1995;7(4):429–38.

Davidovich U, de Wit JB, Stroebe W. Behavioral and cognitive barriers to safer sex between men in steady relationships: implications for prevention strategies. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(4):304–14.

Theodore PS, Duran RE, Antoni MH, Fernandez MI. Intimacy and sexual behavior among HIV-positive men-who-have-sex-with-men in primary relationships. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(3):321–31.

Van de Ven P, Kippax S, Crawford J, et al. In a minority of gay men, sexual risk practice indicates strategic positioning for perceived risk reduction rather than unbridled sex. AIDS Care. 2002;14(4):471–80.

Parsons JT, Schrimshaw EW, Wolitski RJ, et al. Sexual harm reduction practices of HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men: serosorting, strategic positioning, and withdrawal before ejaculation. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 1):S13–25.

Snowden JM, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Seroadaptive behaviours among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: the situation in 2008. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(2):162–4.

McFarland W, Chen YH, Nguyen B, et al. Behavior, intention or chance? A longitudinal study of HIV seroadaptive behaviors, abstinence and condom use. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):121–31.

Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280(5365):867–73.

Ghanem KG, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, Zimba R, Erbelding EJ. Audio computer assisted self interview and face to face interview modes in assessing response bias among STD clinic patients. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(5):421–5.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all study staff and participants without whom this study would not have been possible. This work was supported by the California HIV/AIDS Research Program (CHRP) under grant MC08-LA-710, the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services (CHIPTS) under National Institute of Mental Health grant P30MH058107, the National Institute of Mental Health under grant F31MH097620, the National Institute on Drug Abuse under grants T32DA023356 and K23DA026308, and the UCLA Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) under grant 5P30AI028697 (Core H).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pines, H.A., Gorbach, P.M., Weiss, R.E. et al. Individual-Level, Partnership-Level, and Sexual Event-Level Predictors of Condom Use During Receptive Anal Intercourse Among HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex with Men in Los Angeles. AIDS Behav 20, 1315–1326 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1218-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1218-4