Abstract

Transgender women are at high risk of HIV infection, with younger transgender women (YTW) particularly vulnerable. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) has shown efficacy in reducing HIV acquisition, but little is known about PrEP indication or initiation among YTW. Baseline data from 180 YTW age 18–29 years enrolled in Project LifeSkills, an on-going HIV prevention intervention for YTW, were analyzed to examine factors associated with PrEP indication. The sample (mean age = 23.4, SD = 3.2) was comprised largely of women of color (69 %) and of low socioeconomic status (71 % unemployed). Overall, 62 % met criteria for PrEP indication, but only 5 % reported ever taking PrEP. Factors associated with increased odds of PrEP indication were: PrEP interest (aOR 3.24; 95 % CI 1.44, 7.33), number of recent anal sex partners (aOR 1.23; 95 % CI 1.04, 1.46), and lower collective self-esteem scores (aOR 0.67; 95 % CI 0.47, 0.94). Despite high levels of PrEP indication, there remain low levels of PrEP awareness and uptake among YTW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Transgender women in the U.S. are at very high risk of HIV infection, with an estimated prevalence of HIV infection (laboratory-confirmed) across studies of close to 30 % [1] and an estimated risk 49 times greater in comparison to all adults of reproductive age worldwide [2]. In the U.S., local HIV testing of transgender women in three cities found 12 % previously unrecognized HIV infection, with the highest number detected among those age 20–29 years (i.e., 45 % of all cases) [3], highlighting the vulnerability of young transgender women (YTW), in particular. High levels of sexual risk drive these rates in YTW, fueled by social and economic marginalization and exclusion and related psychosocial problems [4, 5]. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) has shown biological efficacy in reducing risk for HIV acquisition [6–11], but effectiveness at a population-level will depend on utilization among individuals at the highest risk of infection, such as YTW. Although transgender women have been included in PrEP efficacy studies [12], little is known about their awareness, interest, indication or initiation in community-based and practice settings and few data focus specifically on YTW. Prior studies of other high risk populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM) indicate that PrEP awareness and knowledge are related to PrEP uptake [13, 14]. One recent qualitative study that included 30 HIV negative/unknown status MSM and transgender women (in three California metro areas) suggests that while awareness of PrEP is relatively low, expressed interest (once described) is quite high (76 %) [15]. The purpose of this study was to identify correlates of PrEP indication, operationalized using guidelines released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [16], in order to advance prevention science and practice for PrEP implementation in this group at very high risk of HIV acquisition.

Methods

Study Sample

Between March 2012 and October 2014, 243 YTW were enrolled in Project LifeSkills, an on-going multi-site trial in Chicago, IL and Boston, MA testing the efficacy of a culturally-tailored, empowerment-based, and group-delivered HIV prevention intervention for YTW. Participants were recruited using a variety of convenience sampling strategies grounded in community-based participatory research principles with input from local transgender communities in each city, as well as from study staff who were members of the study population (i.e., YTW). These methods included, most prominently, outreach to community-based organizations and events, as well as bars and clubs, and social media outreach and advertisement (e.g. facebook, Craig’s List). Participants completed a 2 h baseline study visit comprised of standardized quantitative assessment via computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) and testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs; urethral gonorrhea and chlamydia). For participation in the parent intervention study, interested individuals were screened for eligibility, according to the following inclusion criteria: [1] age 16–29 years; [2] assigned a male sex at birth and now self-identify as a woman, female, transgender woman, transfemale, male-to-female (MTF), or on the trans feminine spectrum; [3] any HIV serostatus; [4] English-speaking; [5] no plans to move from the local area during the 12-month study period; and [6] self-reported sexual risk (i.e., condomless anal or vaginal intercourse; anal or vaginal intercourse with more than one sexual partner; anal or vaginal sex in exchange of money, food, shelter; or diagnosis with HIV or another sexually transmitted infection in the previous 4 months). All participants were consented for participation. The IRBs at both participating institutions approved the study.

Data Analytic Sample

Baseline data from 180 HIV-uninfected (laboratory-confirmed) YTW were included in these analyses. Participants who were HIV-infected at baseline (19.3 %; n = 47/243) were excluded from this analysis, given that PrEP is a primary HIV prevention strategy. Also excluded were participants with baseline HIV results pending (n = 2) and those with missing data for items used to construct the PrEP indication variable (n = 3; see below). Also excluded from the data analytic sample were YTW ages 16 and 17 years (n = 11) as CDC PrEP recommendations do not include this age range.

Measures

Outcome: PrEP Indication

Items assessing sexual behavior and sexual partner characteristics used for construction of the PrEP indication variable were adapted for YTW from the AIDS Risk Behavior Assessment (ARBA) [17]. A variable was created to reflect indication for PrEP (yes/no) operationalized using a combination of indicators of risk under the CDC guidelines for MSM and heterosexual men and women at high risk of HIV acquisition [16], given the lack of a specific set of criteria for transgender women. These included recent report of sex with an HIV-infected anal and/or vaginal partner, and/or condomless anal sex (receptive or insertive), and/or diagnosis with a STI (laboratory-confirmed via testing described above). We include those reporting condomless anal sex given recent evidence suggesting PrEP is indicated for MSM and transgender women in particular, who report receptive condomless anal sex regardless of partner status [10].

Sociodemographics

Age (in years), race/ethnicity (White, Black/African American, Latina/Hispanic, other minority race/ethnicity), current employment (part-time, full-time, unemployed), level of income (<$10,000 to ≥$80,000 in increments of $10,000), family history (“Did you grow up in a two-parent household?”), and relationship status (“Are you currently involved in a committed relationship with someone who you consider your boyfriend/girlfriend, spouse, or domestic partner?”) were assessed using standard approaches.

Medical Gender Affirmation

Medical gender affirmation was operationalized as reporting ever taking cross-sex hormone therapy, silicone injections, or receipt of genital reconstructive surgery (NB: We considered variations in the operationalization of this variable, including differentiating past versus current hormone use and use of silicone-only as separate variables however, there were too few cases to make this feasible).

Social Marginalization

Indicators of social marginalization included any reported history of transactional sex (“Have you ever traded sexual activity or favors for food, money, a place to sleep, drugs or other material goods?”), homelessness (“In your lifetime, have you ever been homeless at all? That is, you slept in a shelter for homeless people, on the streets, at a friend or relative’s house for a few nights or weeks, or another place not intended for sleeping.”), and jail/incarceration (“Have you ever been in jail/juvenile detention?”).

Access to Healthcare and Healthcare Service Utilization

We measured access to healthcare and healthcare utilization with three items, “What kind of insurance do you currently use to pay for health care?” (coded into three categories: uninsured, public or private); “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?”; “Where do you most often receive health care services?” (dichotomously coded as community-based clinic vs all others).

Substance Use and Mental Health

For use of illicit substances, we used an item from the ARBA that indicated whether or not the respondent ever had sex under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs in the prior 4 months. To measure mental health problems, we used the global score on the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), a 18-item scale of mental health symptoms experienced in the last 7 days [18] (response scale: 0-not at all to 4-extremely; range 0–72).

HIV Knowledge, Condom Use Self-Efficacy, and Number of Anal Sex Partners

For measurement of HIV knowledge, we adapted the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire (HIV-KQ-18) [19] for use with YTW, which include removal of three items referencing risk for non-transgender women and adding five items with specific relevance to YTW (total 20 items; coded as an index, range 0–20). To measure condom self-efficacy, we used the five-item Self-Efficacy for Negotiating Condom Use scale [20], for use with high risk youth. We measured the number of anal sex partners for receptive and insertive anal sex using items from the ARBA (described above).

PrEP Awareness, Initiation, Interest, and Acceptability

After a brief description of PrEP, participants were asked a series of questions, including whether they ever heard of PrEP (before the brief introduction in this study), ever taken PrEP, or ever participated in a PrEP study (yes/no). In addition, they were asked about their level of interest in taking PrEP (once described; 1-not interested at all, 2-somewhat interested, 3-very interested). PrEP acceptability was measured using 10 items assessing the likelihood (1-not at all likely, 2-somewhat likely, 3-very likely) of using PrEP under different scenarios, including dosing (e.g., if taken every day, three times/week), effectiveness (e.g., if 50 % effective) and partner-related variations (e.g., if you only had casual sex partners; items summed as an index with a range of 10–30).

Social Support and Collective Self-Esteem

To measure social support, we used a 6-item scale from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), which measures how often the respondent has someone available in the prior 4 months to help take care of them when sick, help with chores if sick, get together for relaxation, understand problems, make them feel loved and wanted, and borrow money from when needed. Responses options were provided on a frequency scale from 1-none of the time to 5-all of the time (range 6–30). The Collective Self-Esteem Scale (CSES) [21] is a 16-item self-report measure that assesses a person’s thoughts and feelings regarding their social group, which we modified to include reference to the “transgender community.” Using a seven-point scale, participants indicated the degree to which they agree or disagree with statements regarding the reference group (1-strongly disagree to 7-strongly agree). The CSES is divided into four subscales; each subscale consists of four questions. The Membership CSE subscale items assess how “good or worthy” a person feels about being in a particular social group (e.g., “I am a worthy member of the transgender community”). Items from the Private CSE subscale assess how good a person feels about her social group (e.g., “I feel good about the transgender community”). The Public CSE subscale items assess how a person believes others outside the social group judge her group (e.g., “In general, others respect the transgender community”). Finally, items in the Identity CSE subscale assess how important a person’s social group is to her self-concept (e.g., “Being part of the transgender community is an important reflection of who I am”).

Statistical Analysis

SAS v9.3 was used for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the total sample, and for groups stratified by PrEP indication. In crude logistic regression models, we regressed PrEP indication on each independent variable to examine bivariate, unadjusted associations. A multivariable logistic regression model was then fit to examine the factors associated with PrEP indication. The model was adjusted for covariates and potential confounders dichotomized for ease of interpretation (yes/no) and to maximize power in the model (unless otherwise indicated), including study site (Chicago or Boston), age (continuous), race/ethnic minority status (Black/Latina vs White), low income (<$10,000 vs all others), unemployment (vs part-time/full-time employment), history of cross-sex hormone therapy, history of incarceration, history of homelessness, history of sex work, unable to access healthcare in last 12 months, alcohol and/or drug use during sex, partnered/committed relationship, ever heard of PrEP, somewhat/very interested in PrEP (vs not at all interested), acceptability of PrEP (index score).

Results

The sample had a mean age of 23.4 years of age (SD = 3.2). The majority (68.9 %) were women of color (42.2 % Black/African American, 13.3 % Latina/Hispanic, 13.3 % another minority race/ethnicity) and were largely unemployed (71.1 %), with approximately a quarter of the sample reporting no health insurance (23.3 %). Most participants (64.8 %) reported being on cross-sex hormones for medical gender affirmation, with fewer reporting ever injecting silicone (6.7 %) or genital reconstructive surgery (2.8 %). Lifetime indicators of social marginalization were high in the sample, including history of sex work (46.7 %), homelessness (45.7 %), and jail/incarceration (29.4 %).

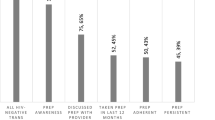

Overall, 61.7 % of the sample met criteria for PrEP indication (7.8 % reported an HIV-infected anal/vaginal sex partner, 59.4 % condomless anal sex, and 2.8 % diagnosed with a STI). Only 30.6 % reported having ever heard of PrEP (before being introduced to it in this study) and 5.0 % reported ever taking PrEP. The majority (68.9 %) reported being “somewhat” or “very” interested in PrEP in the future (42.8 % “somewhat” and 26.1 % “very”). No statistically significant differences were found in PrEP knowledge, initiation (“uptake”), or participation in a PrEP study by PrEP indication in bivariate analysis; however, interest in PrEP was significantly associated with an increased odds of PrEP indication (see Tables 1 and 2).

In an adjusted multivariable logistic regression model, factors associated with a statistically significant increased odds of PrEP indication were: PrEP interest (aOR 3.24; 95 % CI 1.44, 7.33; being “somewhat” or “very” vs “not at all” interested), greater number of insertive or receptive anal sex partners in last 4 months (aOR 1.23; 95 % CI 1.04, 1.46), and lower collective self-esteem membership scores (aOR 0.67; 0.47, 0.94; see Table 3).

Discussion

Given that PrEP awareness and knowledge are associated with PrEP initiation in prior studies, the low levels in YTW found in this study are cause for concern. Furthermore, the high risk of HIV infection among YTW in the U.S. and the demonstrated efficacy of PrEP as a prevention strategy, effectiveness at a population-level will depend on utilization among the highest risk individuals, including YTW. The PrEP care continuum (aka “cascade”) [22], has been put forth as a heuristic framework comparable to the HIV care continuum [23] to focus attention and promote research and practice across the PrEP care process. The initial steps in the continuum, including identifying, screening and assessing interest in PrEP have not been the subject of much research, but are important precursors to uptake. Prior PrEP awareness and knowledge is associated with initiation in individuals indicated for PrEP [14, 24], thus, the low levels of PrEP awareness and initiation in YTW found in this study, are cause for concern.

In contrast to the low levels of PrEP awareness and uptake, both PrEP interest and indication were quite high in this study. A total of 68.9 % reported interest in PrEP and 61.7 % were indicated for PrEP based on a combination of indicators specified in the CDC guidelines for MSM and heterosexual men and women. It is worth noting that while 77 % of those indicated for PrEP were somewhat/very interested in taking it, 57 % of those not indicated for PrEP were similarly interested in taking it. For PrEP providers, this suggests that education on high versus low risk for HIV infection is an important aspect of guidance towards PrEP-related decision-making. Factors related to indication included both interest in PrEP and a heightened sexual risk profile as indicated by significant association with a greater number of anal sex partners. While indicators of social marginalization and healthcare access were not related to PrEP indication, collective self-esteem, specifically the group membership subscale of the CSES was related to PrEP indication, which may reflect increased vulnerability and risk for HIV infection among isolated YTW specifically. Incorporating group membership and empowerment to increase transgender collective self-esteem, as well as linking YTW to other YTW for peer support and health navigation, represent potential components to improve the PrEP care continuum for this population, as well as to ensure delivery of gender affirming HIV prevention services.

To date most PrEP research has occurred either within the context of controlled environments such as feasibility and acceptability trials, clinical efficacy trials, or demonstration expansion projects with clinic-based samples and where PrEP medication is dispensed to participants as part of study protocols. Little-to-no research had been published on issues on “real world” implementation of PrEP among community-based samples of YTW, which will be needed to demonstrate effectiveness. The combination of high interest and indication found here present an opportunity for PrEP implementation and related implementation science research among YTW.

Limitations

Findings in this study are limited by both the nature of the study sample and the self-reported measures. This sample reflects a high risk group of YTW targeted for HIV prevention per the goals of the parent study, who may have relatively high levels of motivation to participate in HIV-related programming. In addition, we limited the parent study sample to individuals who were unlikely to move from the study area in order to maintain a high rate of retention in the study over time, which may have excluded highly transient individuals who may be at high risk of HIV infection for the PrEP sub-analysis. Thus, given both the convenience sampling method and our inclusion criteria, findings may not generalize to all urban YTW. Furthermore, given the relatively young age of participants, lifetime measures of transactional sex, incarceration, and homeless were used as indicators of social marginalization. Although a lifetime measure may not necessarily correspond to current social marginalization, it is reasonable to assume that these are markers of risk in this highly vulnerable group of YTW. Another limitation of our study was the measure of PrEP initiation, which was self-reported and not verified via blood draw for drug levels. A strength of the study, however, is the inclusion of two sites in different U.S. cities which provided greater diversity and allowed us to enroll one of the largest cohorts of YTW to our knowledge.

Conclusions

We conclude that interventions are needed for YTW that promote engagement the PrEP continuum of care (i.e., assessment of PrEP indication, interest, initiation), particularly given evidence of the association of PrEP indication with both higher interest and an enhanced behavioral risk profile.

References

Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):1–17.

Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22.

Schulden JD, Song B, Barrosb A, Mares-DelGrasso A, Martind CW, Ramireze R, et al. Rapid HIV testing in transgender communities by community-based organizations in three cities. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:101–14.

Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper G. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:230–6.

Garofalo R, Osmer E, Sullivan C, Doll M, Harper G. Environmental, psychosocial, and individual correlates of HIV risk in ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J HIV/AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2006;7(2):89–104.

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99.

Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, Irvin R, Mulligan K, Mayer K, et al. Bone mineral density in HIV-negative men participating in a tenofovir pre-exposure prophylaxis randomized clinical trial in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23688.

Hosek SG, Siberry G, Bell M, Lally M, Kapogiannis B, Green K, et al. The acceptability and feasibility of an HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trial with young men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;62(4):447–56.

Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, Chillag K, Mayer K, Thompson M, Grohskopf L, et al. Sexual risk behavior among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men participating in a tenofovir preexposure prophylaxis randomized trial in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;64(1):87–94.

Buchbinder SP, Glidden DV, Liu AY, McMahan V, Guanira JV, Mayer KH, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men and transgender women: a secondary analysis of a phase 3 randomised controlled efficacy trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:468–75.

Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–9.

Escudero DJ, Kerr T, Operario D, Socias ME, Sued O, Marshall BD. Inclusion of trans women in pre-exposure prophylaxis trials: a review. AIDS Care. 2014;28:1–5.

Bauermeister JA, Meanley S, Pingel E, Soler JH, Harper GW. PrEP awareness and perceived barriers among single young men who have sex with men. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(7):520–7.

Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, Cohan D, Weber S, Sachdev D, et al. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001613.

Galindo GR, Walker JJ, Hazelton P, Lane T, Steward WT, Morin SF, et al. Community member perspectives from transgender women and men who have sex with men on pre-exposure prophylaxis as an HIV prevention strategy: implications for implementation. Implement Sci. 2012;7:116.

CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: 2014 clinical practice guideline. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Bryant FB, Wilson H, Weber-Shifrin E. Understanding AIDS-risk behavior among adolescents in psychiatric care: links to psychopathology and peer relationships. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(6):642–53.

Derogatis L. Brief symptom inventory: administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems Inc; 1993.

Carey M, Schroder K. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief hiv knowledge questionnaire. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:172–82.

Rotheram-Borus M, Murphy D, Coleman C, Kennedy M, Reid H, Cline T, et al. Risk acts, health care, and medical adherence among HIV+ youths in care over time. AIDS Behav. 1997;1:43–52.

Luhtanen R, Crocker J. Collective self-esteem scale: self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1992;18:302–18.

Liu A, Colfax G, Cohen S, Bacon O, Kolber M, Amico KR, et al., editors. The spectrum of engagement in HIV prevention: proposal for a PrEP cascade. In: 7th International conference on HIV treatment and prevention adherence. Florida: Miami Beach; 2012.

McNairy ML, El-Sadr WM. A paradigm shift: focus on the HIV prevention continuum. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(1):S12–5.

Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, Doblecki-Lewis S, Postle BS, Feaster DJ, et al. High interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV-infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:439–48.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the LifeSkills Study Team in Boston and Chicago for their contribution to sample accrual and data collection and Abigail Muldoon for preparation of data for analysis. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH094323. The project described was also supported, in part, by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Grant Number UL1TR000150 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (CTSA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The CTSA is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT01575938.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuhns, L.M., Reisner, S.L., Mimiaga, M.J. et al. Correlates of PrEP Indication in a Multi-Site Cohort of Young HIV-Uninfected Transgender Women. AIDS Behav 20, 1470–1477 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1182-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1182-z