Abstract

Given the popularity of social media among young men who have sex with men (YMSM), and in light of YMSM’s elevated and increasing HIV rates, we tested the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a live chat intervention delivered on Facebook in reducing condomless anal sex and substance use within a group of high risk YMSM in a pre-post design with no control group. Participants (N = 41; 18–29 years old) completed up to eight one-hour motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral skills-based online live chat intervention sessions, and reported on demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral characteristics at baseline and immediately post-intervention. Analyses indicated that participation in the intervention (n = 31) was associated with reductions of days of drug and alcohol use in the past month and instances of anal sex without a condom (including under the influence of substances), as well as increases in knowledge of HIV-related risks at 3-month follow-up. This pilot study argues for the potential of this social media-delivered intervention to reduce HIV risk among a most vulnerable group in the United States, in a manner that was highly acceptable to receive and feasible to execute. A future randomized controlled trial could generate an intervention blueprint for providers to support YMSM’s wellbeing by reaching them regardless of their geographical location, at a low cost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Young men who have sex with men (YMSM) represent the group with the highest incidence of new HIV infections in the U.S. and one of the few risk groups in the U.S. with increasing rates of infection [1]. Ninety one percent of all HIV diagnoses among adolescent males ages 13-19 were attributed to same-sex contact, and the greatest percentage increase in HIV incidence between 2006 and 2009 occurred in YMSM 13-24 years of age [2–4]. The primary mode of HIV acquisition for MSM is through condomless anal intercourse, [5–13] while drug and alcohol use have been shown to exacerbate the odds for risky sexual encounters [4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14–23]. Both condomless sex and substance use are relatively normative within gay communities and frequently co-occur [9, 10, 12]. Further, sexual risk behaviors among MSM are driven by experiences of gay-, race-, and HIV-related stigma and discrimination [5, 24–26] and poor mental health [27–34] Thus, effective HIV prevention approaches for YMSM might benefit from simultaneously addressing these determinants of sexual health and co-occurring health outcomes [27, 35], some of which we apply in the current intervention.

Effectively engaging YMSM in HIV prevention also requires appealing and convenient delivery modalities, including taking advantage of popular venues [36–39]. Social media, or platforms where virtual networks of individuals connect to communicate interactively online, represents one such modality with particular appeal, accessibility, reach, and cost-effectiveness for YMSM [40]. Similar to other groups, YMSM demonstrate a well-established reliance on electronic means of communication, including social media technology that enables meeting sex partners and forming sexual connections [41–43]. YMSM, in particular, learn about sex and initiate meaningful social and sexual connections on the internet, increasingly through social media technologies [44]. Virtual social and sexual networking venues are increasingly important in the lives of many YMSM [45], with social media especially forming a core component of young cohorts’ social and sexual development. Importantly, leading social and sexual lives through social media may increase YMSM’s risk for HIV infection [42, 46–48]. Therefore, social media platforms, such as Facebook, represent promising avenues for reaching YMSM for the purposes of HIV prevention that would resonate with their contemporary lifestyles and sexual health needs [45, 49].

In-office HIV prevention interventions, while generally effective [50], are not preferred by many MSM, who are more likely to delay or avoid seeking health services compared to heterosexual men due to perceived provider bias and a relative lack of visibility of competent services for this population [51]. In-office health promotion interventions may not be highly desirable for YMSM in particular given that they rely heavily on the internet for health information and as a primary source of socialization, communication, and learning [44]. In fact, YMSM report strong willingness to receive health promotion intervention services online [52]. They indicate significant openness to engaging in health-related online communication with providers about mental, sexual, and relationship health, in addition to discussing substance use, HIV risk reduction, and developmental influences on both [52]. Consequently, several online interventions have shown success in recruiting and retaining MSM [40, 53–55] and favorably impacting condom use [53, 56–59], mental health [57], HIV-related knowledge [53, 54], HIV risk reduction self-efficacy [53, 54], number of sex partners [57], HIV testing behavior [39, 60], and HIV status disclosure [56, 59]. However, to our knowledge, no interventions to-date have taken advantage of social media platforms to most effectively deliver HIV prevention to YMSM through these frequently used, highly convenient venues where many YMSM conduct their social and sexual lives.

In response to the internet’s having become a powerful tool for both HIV risk and prevention [36], we created Motivational Interviewing (MI) Communication about Health, Attitudes, and Thoughts (MiCHAT) [61], a pilot project to test the feasibility and acceptability of an online intervention to reduce HIV risk among YMSM. Towards this goal, we iteratively modified an efficacious MI-based in-office intervention [7] for live chat internet delivery via social media. The resulting intervention, MiCHAT, integrates two intervention strategies with substantial empirical support for reducing health-risk behaviors: MI to enhance participants’ motivation to reduce health risks and increase protective behaviors [62–70], and cognitive behavioral skills training (CBST) to further promote behavior change [71]. MiCHAT incorporates a focus on personal, social, and contextual determinants of HIV risk, including substance use, gay community norms, mental health, and gay-related stigma among MSM into motivational and skills-building components, as well as real-time behavioral tracking of risk behavior and relevant contexts.

In this paper, we present the results of the pilot study testing the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of this first MI/cognitive behavioral skills-training (CBST)-based live chat social media HIV prevention intervention among YMSM who both engage in condomless anal sex with high-risk male partners and use substances. We hypothesize that intervention participants will demonstrate a significant decrease in HIV risk from baseline to follow-up in primary outcomes, which include condomless anal sex and drug/alcohol use. Additionally, given psychosocial correlates of HIV risk, we postulate that participation in this intervention will lead to significant improvement in secondary outcomes, which include mental health (e.g., depression), gay-related stigma, and components of the IMB model.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Between February and December 2012, potential participants were recruited via Facebook (16.4 %), Craigslist (2.7 %), e-blasts sent by gay-themed-event promoters (15.8 %), Adam4Adam banner ads (6.2 %), and Grindr pop-up ads (6.1 %). Potential participants clicked on a link to a secure preliminary eligibility screener. We also screened potentially eligible participants from former studies who had indicated an interest in future research (30.1 %). Finally, participants were also recruited through friend referral (6.8 %), as well as field recruitment (10.7 %), where recruiters screened potential participants for eligibility using iTouch devices (a small computer with Wi-Fi capabilities that can be used for data collection in the field) in a variety of venues catering to gay, bisexual, and other MSM—including bars, sex venues, streets in predominately gay neighborhoods, and LGBT community events. Potential participants recruited online and in the field had the option to provide contact information at the end of the screener, in a separate survey, and the research staff later contacted them to describe the study, conduct a more thorough eligibility screening by phone, and schedule those who were eligible and interested for a hybrid phone-internet baseline appointment.

We conducted 146 eligibility screenings by phone, of which 41 (28 %) were eligible. Eligible participants were: born and self-identified as male; 18–29 years of age; reported a negative or unknown HIV status; had used drugs—specifically cocaine, methamphetamine, or ecstasy—on at least five of the past 90 days; and had at least one incident of condomless anal sex with an HIV-positive or status-unknown main partner, or casual partners of any HIV status in the past 90 days; or, had used the aforementioned drugs with an instance of condomless anal sex meeting the above criteria. The Institutional Review Board of the investigators’ institution approved all procedures.

Consent Process

Prior to the baseline assessment, participants were asked to email an image of their photo identification to the Project Coordinator for age confirmation. Once age eligibility was verified, copies of the participants’ identification were destroyed to prevent potential breaches of confidentiality. At the time of the baseline assessment, project staff called the participants and emailed them a link to an electronic version of the consent form. The staff read through the consent form with the participants, explained all study details, answered their questions, and clarified any points of confusion. Participants then provided an electronic signature indicating their consent to participate in the study, after which they received an electronic version of the consent form. None of the YMSM undergoing the consent process refused participation.

Assessments

There were two types of assessments, a baseline and an immediate post-intervention follow-up, both of which were audio-recorded for verification of protocol fidelity and data quality assurance purposes. Each assessment contained (1) a phone interview portion to record sexual and substance use behavior in the prior 30 days (Timeline Follow Back [TLFB] calendar [72, 73], described below), assess readiness and motivation to change drug use and condomless anal sex behaviors (“Contemplation Ladders,” [74, 75]); (2) and a self-administered assessment of psychosocial characteristics (e.g., mental health, stigma), to which participants were sent a link to an online survey following the phone interview. Participants had 1 week to complete the online survey.

In order to minimize potential bias created by utilizing the same staff for assessment and intervention delivery, different staff members conducted the TLFB assessment and delivery of MI intervention sessions (see counselor description below). Lastly, participants completed a post-intervention assessment mirroring the baseline assessment procedures and measures, immediately after the last intervention session for those completing all eight sessions or after several attempts were made to engage participants in completing as many sessions as possible (See Fig. 1). This follow-up assessment occurred approximately 3 months after baseline. Participants were compensated $40 in cash for each completed assessment. A final evaluation interview, conducted by study investigators over the phone and compensated with $30 in cash, provided in-depth qualitative feedback from participants’ experiences with the study. All participants spoke English and completed assessments and intervention sessions in English.

Intervention

MiCHAT was based on an efficacious in-office HIV prevention intervention delivered in four sessions to non-treatment-seeking YMSM who engaged in condomless anal sex and substance use [7]. To translate the in-office intervention for delivery via Facebook chat, our team conducted a series of focus groups and interviews with 13 participants from the original in-office intervention to gather suggested adaptations. Former in-office intervention participants [5–7] were contacted to provide feedback on their experiences with the study and its adaptation for online delivery. To obtain diverse perspectives for the development of MiCHAT, we contacted participants who (1) completed the minimal intervention dose of at least 3 of 4 sessions, (2) completed only 1–2 sessions, and (3) refused to participate in intervention sessions but agreed to be assessed over 12 months. Two of the investigators conducted the interviews and focus groups, and took notes of participant suggestions regarding how to create a feasible and acceptable online intervention from the original in-office intervention. The investigators then isolated elements relevant to modifying the intervention, and revised the intervention accordingly, and then presented the revised intervention to the participants for final feedback. This intervention development process and resulting intervention content is described in detail elsewhere [61] and summarized in Fig. 2 here. In addition to including modifications for facilitating social media delivery (e.g., guidance on online communication and online rapport building, confidentiality protections), the resulting MiCHAT intervention included new intervention content. This new content included writing exercises and homework assignments to address psychosocial and contextual risk factors such as stigma and mental health, as relevant, but not as direct targets of the intervention. CBST exercises were added to complement the MI treatment base for participants who were motivated to enact behavior change. CBT exercises included effective communication, self-monitoring, positive events scheduling and behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, and exercises for strengthening and accessing social support as an effective coping strategy. Finally, counselors distributed links to online informational resources as relevant to each participant’s risk behavior.

Thus, counselors used the MI treatment base to provide information about substance use and sex risk, enhance motivation and personal responsibility, and establish goals for reducing both target behaviors. CBT was introduced in the latter sessions to help motivated participants achieve their health goals. In its deployment of information and behavioral skills against a motivation-enhancing backdrop, MiCHAT adheres to the principles of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model of health behavior change [76–78].

Counselors, Training, Supervision and Intervention Delivery

Seven Master’s- and PhD-level therapists delivered the intervention and possessed prior experience delivering MI and CBST intervention techniques in research and clinical settings. A licensed clinical psychologist conducted the initial training, led weekly individual and group supervision, and provided feedback on 95 % of sessions. Training occurred through a two-day didactic seminar and completion of a mock course of treatment. A treatment manual, developed through the process described above and detailed elsewhere [61], guided therapists in delivering the treatment.

Sessions took place over the chat feature of Facebook. The Project Coordinator created secure, anonymous study accounts for each participant. Facebook accounts contained no identifying information; instead, participants received a unique numeric identification number. Similarly, therapists created Facebook accounts specifically for use in this study that contained their professional picture, educational and professional background, and resources for participants to use throughout the study (e.g., links to psychosocial and health informational resources.) The highest security settings allowed by Facebook were maintained throughout the study for each participant. To further protect participants’ privacy and confidentiality, at the beginning of each intervention chat session, the therapists verified that participants were in private spaces where they did not risk others reading their chat session. At the end of each session, the therapists asked participants to clear the text of the chat session and their internet browsing history. We configured the account settings so that no participants could see the profiles or existence of other participants. We encouraged participants not to post personal information on their study profiles, including pictures or identifiable information. At scheduled times, the counselor and participant signed into their study Facebook accounts and opened chat windows, where they completed each week’s session. All chat-sessions generated downloadable text from the secure Facebook interface, which was reviewed in supervision.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported their age, race/ethnicity, sexual identity, income, education, and relationship status (Table 1).

Primary Outcomes

The outcomes of interest—condomless anal sex with a casual partner (overall and under the influence of drugs/alcohol) and number of days of drug use—were collected using a 30-day timeline follow-back interview (TLFB.) [72, 73] Critical life events (e.g., vacations, birthdays, parties) were reviewed retrospectively to prompt recall of daily sex and drug use behavior. The TLFB has previously demonstrated good test–retest reliability, convergent validity, and agreement with collateral reports for drug abuse [79] and for sexual behavior [80, 81], and has been utilized with substance-using YMSM [19, 62, 82]. Each day was coded for drug use (alone and with sex), heavy drinking (5 or more drinks that day), sexual partner and type (main/casual), and condom use. Staff received extensive training and supervision in the administration of the TLFB and maintained good rapport throughout. They were also trained in being non-judgmental and sex-positive in order to facilitate honest self-reports and to respect the priorities and behaviors of all participants.

Psychosocial Outcomes

Participants self-administered several online measures related to the IMB model and gay-related stigma and mental health (specifically anxiety and depression), which have been shown to be associated with HIV risk [83, 84]. The information component of the IMB model was measured with two scales pertaining to the effects of drug use and sexual health knowledge. The former comprised of seven multiple choice items about the effects of cocaine, methamphetamine and ecstasy, with some item examples being “Long-term use of crystal meth can cause..” and “Which types of drugs should you not take together…?” [85]. The latter was an adaptation of the Sexual Health Knowledge Questionnaire for HIV-negative MSM (18 items in a true/false format, α = 0.70) [86]. Item examples are: “Having another STD makes it easier for an HIV+ person to give HIV to an HIV-negative partner.” and “HIV can be transmitted through oral sex, but the risks are much lower than for anal or vaginal sex.” Participants received a point for each correct response, therefore higher scores indicated more accurate HIV-related sexual health knowledge.

The motivation component of the IMB model comprised of motivation to change drug use and condomless anal sex behaviors (“Contemplation Ladders.” [74, 75]) Each of the ladders entailed ten items (configured as rungs on a ladder) pertaining to how ready one was to change their risk around drug or condom use, respectively. For example, a participant would select number 1 to indicate no intentions to change behavior (e.g., “I enjoy sex without condoms and have decided to never change it. I have no interest in using condoms.”); a score of 10 indicates that a change has occurred to minimize risk behavior and it is believe to be permanent (e.g., “I have changed my drug use and will never go back to the way I used drugs before.”) The Ladders instrument was delivered during the phone portion of the assessment. Participants were emailed the actual instrument ahead of time and the assessor read it along with them. Participants were asked to verbally communicate their answer to the assessor, who circled the correct number on a hard copy in the office.

The behavioral self-efficacy skills component of the IMB model consisted of the Drug Taking Confidence Questionnaire and Safer Sex Efficacy Questionnaire. The Drug Taking Confidence Questionnaire (α = 0.91) measures individuals’ confidence in their ability to resist the urge of using drugs in contexts that are typically considered conducive to such behaviors, which was rated on a Likert-type scale with response options from 1 (“not at all”) to 6 (“completely”.) Example items are: “How confident would you feel about being able to resist the urge of using drugs if… you wanted to celebrate with a friend” or “…you had been drinking and thought about using drugs.” Lastly, participants’ sense of control over and skill regarding their condom use was measured using the 13-item Safer Sex Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (α = 0.94.) [87, 88] Participants were asked “How confident are you that you could avoid having anal sex without a condom…” across a variety of different sexual situations (e.g., “when you really want sex?” and “when you are drunk or high on drugs?”). Responses range on a Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (extremely confident) and were summed to form an overall score ranging from 13 to 65.

The Gay-Related Stigma Scale [25] is a modified version of the HIV Stigma Scale [89]. There are two components of the stigma scale, 10 items each, with response options on a scale from 1 to 4. The first pertains to personally perceived stigma from friends and family in relation to disclosing sexual orientation (α = 0.93,) and includes items such as “I have been hurt by how people reacted to learning that I’m gay or bisexual” or “Since realizing that I’m GBT, I feel isolated from the rest of the world.” The second addresses ways in which one conceals their sexual minority identity due to stigma (α = 0.80,) with item examples being “I worry that people may judge when they learn I’m GBT” or “Telling someone I’m GBT is risky.” Anxiety and depression scores were obtained with the Brief Symptom Inventory Scale [90], a 12-item scale (α = 0.85). Participants are asked, on a Likert scale, whether they experienced a variety of symptoms in the previous 7 days, such as “nervousness or shakiness inside” or “feelings of worthlessness.”

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed to assess sample characteristics and the distribution of study variables. We compared participants who attended at least one intervention session to those who did not attend the intervention using Chi square tests and independent samples t tests. To evaluate changes in primary outcomes from baseline to 3-month follow-up, we used nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon signed rank tests), given the skewed distribution of the outcome variables. For secondary outcomes, which were normally distributed, we used paired samples t tests. For both primary and secondary outcomes, we expected to have a power of 0.95 at an alpha of 0.05 to detect a small effect size (Cohen’s d) based on a priori powered analyses, which were conducted using G-power (version 3.1), which we used to estimate the expected power and effect size for each of our analyses. Primary analyses included the 27 participants who completed both the baseline and follow-up assessments; however, we also used sensitivity analyses for the subsample of participants who attended at least one intervention session and also completed the follow-up assessment (n = 22). Results of these analyses were unchanged, therefore, in order to present the most conservative results, we present findings from analyses based on the sample of 27 participants with both baseline and follow-up assessments completed.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Forty-one YMSM enrolled in MiCHAT and completed the baseline assessment (see Table 1), with nearly half the sample being YMSM of color (46 %). Participants’ mean age was 25 years (SD = 3.22) with a range of 18 to 29 years old. The sample was diverse in terms of socioeconomic status; 46 % earned less than $30,000 annually and 34 % reported less than a bachelor’s degree. The majority of the sample (85 %) identified as being gay. All participants reported engaging in anal sex without a condom in the previous 30 days before baseline, with the average number of anal sex acts without a condom during that time being 7.63 (SD = 16.95), while the average number of anal sex acts without a condom under the influence of alcohol or drugs was 5.05 (SD = 16.07). Participants reported an average of 9.44 (SD = 7.22) heavy drinking days in the 30 days prior to their baseline assessment, and an average of 5.07 (SD = 6.28) drug-use days.

Session Attendance

Thirty-one of the forty-one participants (75.6 %) completed a baseline assessment and attended at least one of the eight intervention sessions (see Fig. 1 for enrollment and retention details). There were no significant differences in session participation by recruitment source. Those who attended intervention sessions (n = 31) had a significantly higher number of drug days at baseline than those who did not attend any intervention sessions (n = 10) (M = 5.9 versus M = 2.6; p < 0.05). No significant differences were found in age, race/ethnicity, income, education, or frequency of drug use or engagement in anal sex without a condom between those who attended sessions and those who did not. Among those who attended at least one intervention session and completed the follow-up assessment (n = 27) the average attendance was 5.74 (SD = 3.29) sessions. Of the 31 participants who engaged in intervention sessions, 19 (61 %) completed the minimum dose of at least five sessions (which contain the core motivational interviewing components of the intervention).

Efficacy of the Intervention

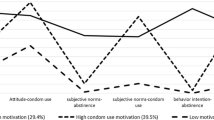

Figure 3 and Table 2 present efficacy results. We found significant reductions in risk behaviors between baseline and follow-up (Fig. 3). For primary outcomes, we found significant differences between baseline and follow-up assessments, such that the intervention was associated with decreased HIV-related risk behaviors in the past 30 days for the number of anal sex acts without a condom (M = 8.96 vs. M = 3.11, p = 0.042; dz = 0.40) and number of anal sex acts without a condom under the influence of drugs (M = 6.89 vs. M = 0.81, p < 0.001; dz = 0.44) (Fig. 3). We also found decreases in the number of heavy drinking days (M = 10.70 vs. M = 8.52, p = 0.082) and number of drug days (M = 5.52 vs. M = 3.30, p = 0.073), but the effect sizes for both these analyses (dz = 0.29 and 0.38, respectively) indicate that these analyses were underpowered.

Changes were also found in participants’ information/knowledge regarding substance use and sexual risk, consistent with IMB model components [77, 91] (Table 2). Specifically, there were significant increases in knowledge of sexual risk from baseline to follow-up (M = 9.52 vs. M = 10.74, p = 0.01) and increases in knowledge of the deleterious effects of substance use (M = 14.40 vs. M = 15.07, p = 0.05). There were no statistically significant changes from baseline to follow-up in participants’ motivation to reduce condomless anal sex acts and drug use (the Drug and Sex Ladders) or behavioral efficacy skills (Drug Taking Confidence and Safer Sex Efficacy Questionnaires) (Table 2). Lastly, our analyses indicated reductions in depressive symptoms (M = 14.48 vs. M = 13.37, p = 0.19) and gay-related concealment stigma (M = 20.33 vs. M = 18.18, p = 0.18) (Table 2). The reductions in depression and stigma were not statistically significant, but that the effect size for the latter (dz = −0.35) argues for the stigma analysis being underpowered. Further, the effect size for depression (dz = −0.10) is close to negligible. Results were unchanged when we conducted the same analyses on the 22 participants who attended at least one session and completed the follow-up assessment.

Acceptability and Feasibility of the Intervention

The one-hour phone interviews conducted by investigators with 23 participants (83 % of session participants) at the end of the study revealed an overwhelmingly positive evaluation of the project, including its scope, structure, and impact. We inquired about motivation for participation, intervention structure, length, content, comfort with communicating sensitive information via chat, and privacy and confidentiality concerns, as well as ease of navigating a virtual therapeutic relationship with counselors. Common reasons for participation were intrigue over this type of counseling modality and a desire to contribute towards “the good of the community.” Session and intervention duration were both found to be appropriate for orienting participants towards their goals and providing them with skills to achieve them. Participants deemed the content to be relevant because “it was about me.” Many expressed gratitude for having had a rare or first opportunity to explore issues of sexual health, risky circumstances, partnerships, and drug use with someone they deemed to be both non-judgmental and professional. The intervention begins by asking participants to choose their top three priorities in an electronic “card sort exercise,” [92] which emerged as highly revealing and useful. Specifically, participants are directed during the first session of the intervention to a link where they view a comprehensive list of values/priorities (e.g., health, honesty, appearance, finances, etc.), which they weigh in relation to their current standing and desired future achievements. Based on these considerations, they select three values that are most important to them and to which they return throughout the MiCHAT counseling sessions. In their final evaluation interviews, participants expressed that this exercise prompted them to “take a step back and look at my life and patterns,” and “stop and think” about the reasons behind behavior, or “have a bird’s eye view of my life.” Participants reported that conversations with counselors permeated their subsequent navigation of sexual and social contexts involving risk and substance use. They began viewing these contexts critically and exerting self-efficacy in changing their approach to risky scenarios, distancing themselves from “party and play” peer groups, and seeking alternative modes of socialization that were still fulfilling and less “harmful” to their health. Our continuous efforts to protect participants’ online privacy and confidentiality were effective in that not one interviewed participant reported privacy concerns and all expressed full trust in our commitment and ability to protect their data and identities. All interviewed participants, without exception, reported building a trustworthy therapeutic relationship with their counselors, with whom they comfortably shared sensitive information related to their substance use and sex lives as they considered changing these behaviors. Participants made several recommendations for improvement, such as delving into core issues (e.g., risky behaviors) earlier in the process by spending less time focused on study logistics, which we provided amply to reassure participants of their confidentiality and privacy being secured, and to minimize miscommunication in the absence of non-verbal cues and voice inflection. Some participants also expressed a desire for speedier session communication with counselors, which was in some cases impeded by text use, and suggested supplementing the intervention with voice or image media.

Discussion

While several interventions have demonstrated efficacy in reducing HIV risk behaviors among YMSM, the increasing incidence of HIV infection among this group calls for continued strides in intervention content and delivery modalities [38, 50, 83, 93, 94]. The MiCHAT intervention described here integrates MI and CBT exercises to increase knowledge, motivation, and behavioral skills for reducing sex risk and substance use. By delivering MiCHAT via Facebook, the most popular social media platform among young people including YMSM, we capitalized on the familiarity and accessibility of this venue where YMSM already conduct their lives [39]. Results indicate that participation in MiCHAT was associated with reductions in condomless anal sex overall, condomless anal sex under the influence of substances, and substance use (cocaine, ecstasy, methamphetamine, heavy drinking) at the immediate post-intervention assessment. Participants additionally reported significant engagement with the intervention, trust in their counselors, and that the intervention helped them consider their values, assess health risks, reflect on their goals and begin working towards them.

Given that HIV infection among YMSM is driven by several factors, such as stigma, we also examined the influence of the intervention on this determinant of risk. We found that participation in MiCHAT was associated with reductions in concealable stigma, despite the fact that the intervention did not specifically target this aspect directly. Given that gay-related stigma is associated with HIV risk behavior [35], our findings suggest important avenues for future work [5, 6]. Importantly, MiCHAT participation was associated with an increase in knowledge about sex and substance use risk, although not with self-reported motivation to change or self-efficacy for change, thus, only partially supporting the IMB model. This singular effect for improving knowledge, but not motivation and behavioral skills, is consistent with other studies where not all IMB model components were validated in relation to HIV risk [84], and may suggest a lack of generalizability of this model across contexts, including online interventions or application to younger cohorts of MSM [5].

Nevertheless, results suggest that MiCHAT represents a promising intervention in terms of content and delivery modality, capable of reducing condomless anal sex, substance use, and their co-occurrence among YMSM. Preliminary support also exists for MiCHAT’s potential ability to impact important contextual determinants of these risk behaviors, such as gay-related stigma. Incorporation of such targets in a next iteration of a larger MiCHAT study might lead to significant reductions in stigma, which might serve as a mediator of the intervention’s impact on health-risk behavior. Specifically, studies have also shown that HIV risk messages may be less effective for those with high levels stigma [95] and that HIV risk is associated with increased levels of stigma [5, 6, 96]. Thus, alleviating the impact of perceived stigma may lead to reductions in risk behavior by allowing participants to be more fully receptive to the intervention’s message and goals. Preliminary efforts to develop such interventions are currently underway [35].

A particularly notable finding was related to substance use, which has been shown to exponentially increase the odds of HIV transmission [6–8, 10]. Specifically, it was intriguing that those who engaged in sessions reported significantly more substance use and lower motivation to change this behavior at baseline than those who did not complete sessions. This, in combination with the finding that drug use days were significantly reduced at follow-up, shows the promise of this intervention for impacting substance use, especially if scaled up and available in a completely mobile format for men regardless of their geographical location.

Several limitations suggest possible future research directions. First, given the small sample size, the present study was underpowered to detect statistically significant effects in all outcomes. Further, the small sample of this pilot did not allow us to assess mediation or moderation effects to uncover the mechanisms through which this study effected behavior change, and the men for whom it was particularly likely to be efficacious. The lack of a control group, while appropriate for this preliminary feasibility and acceptability trial, precludes causal inference and the ability to rule out a therapeutic effect of time. While the effect sizes were small-to-moderate, it is plausible that the intervention did not have an impact beyond the effects of undergoing pre-post intervention assessments. Further, without including longer follow-up assessments, we are unable to determine the durability of the intervention effects. Future tests of MiCHAT’s efficacy, therefore, should employ randomization, a control group, sufficient sample size, and repeated follow-up assessments. Future research might also seek to deliver MiCHAT via a range of social media technologies, including fully mobile platforms which can further increase accessibility and appeal for reaching YMSM, especially those who are highly mobile. Lastly, participants’ feedback based on their intervention participation identified potential barriers to technology-based intervention delivery, such as the need to describe online study protections in depth, and constitute useful suggestions for a next iteration of this study.

Future research ought to compare MiCHAT against an in-office MI/CBT intervention or against a social media control intervention [39, 97–99] without the enhanced components of MiCHAT, in order to determine MiCHAT’s causal role in health behavior improvement and potential mechanisms of change, such as reduced depression [27, 35]. A fast-developing modality of reaching YMSM includes mobile and application (app)-based avenues, for which MiCHAT would constitute an ideal candidate given its strong potential for mobile adoption, as well as some of our participants’ desire to access sessions on their mobile devices. A more mobile version of MiCHAT could also take advantage of real-time risk monitoring and behavioral feedback [100, 101]. Further, participants in MiCHAT suggested alternatives to text-based delivery, such as voice (phone), and/or in combination with live video chat. These media alone or in configuration with each other may circumvent some difficulties tied to constraints of MiCHAT’s text-based delivery, specifically slower pace, variability in writing proficiency, and the lack of non-verbal cues in text exchanges, which are otherwise essential in communication.

Delivering a MI/CBT intervention over social media presents challenges. For example, former in-office intervention participants who contributed to the development of MiCHAT expressed concerns with privacy and confidentiality, and were to an extent reluctant to envision discussions of individuals’ sexual lives on a platform (such as Facebook), where they usually engage with others primarily in a non-sexual discourse [61]. Additionally, accountability for session attendance could be attenuated by the lack of face-to-face contact, which may have contributed towards suboptimal session completion rates. However, these challenges are balanced by benefits, including the ability of social media interventions to reach geographically isolated YMSM with scant resources [36, 37, 53], the fact that such interventions attain high acceptability by taking advantage of familiar and popular venues for YMSM, and their cost-effectiveness in supporting the well-being of YMSM [93].

In sum, MiCHAT represents a feasible and acceptable intervention with preliminary efficacy for reducing condomless sex, substance use, and their co-occurrence among YMSM. This study also demonstrates preliminary support for improving HIV risk knowledge and psychosocial factors, such as the impact of stigma. Future randomized controlled trials are warranted to further establish the efficacy of this intervention, as well as test the underlying mechanism of its effect. While technology-based interventions tested and disseminated over the internet are promising, understanding how to better adapt these interventions in clinical practices and community based settings will be critical to their success.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/gender/msm/facts/index.html. Accessed 1 April 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS and Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. HIV Fact Sheet. 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyYouth/sexualbehaviors/pdf/hiv_factsheet_ymsm.pdf. Accessed 2 Feb 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHBS: HIV Risk and Testing Behaviors Among Young MSM. 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/msm/ymsm.htm. Accessed 2 Feb 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance in Adolescents and Young Adults. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis JE, Walker JJ, Bamonte A, Golub SA, Parsons JT. Age cohort differences in the effects of gay-related stigma, anxiety and identification with the gay community on risky sex and substance use. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):340–9.

Parsons J, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub S. Predictors of day-level sexual risk for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1465–77.

Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub SA. A randomized controlled trial utilizing motivational interviewing to reduce HIV risk and drug use in young gay and bisexual men. Journal of Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(1):9–18.

Halkitis P, Green K, Carragher D. Methamphetamine use, sexual behavior, and HIV seroconversion. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2006;10(3–4):95–109.

Halkitis P, Moeller R, Siconolfi D, Jerome R, Rogers M, Schillinger J. Methamphetamine and poly-substance use among gym-attending men who have sex with men in New York City. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(1):41–8.

Halkitis P, Parsons J. Recreational drug use and HIV risk sexual behavior among men frequenting urban gay venues. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2002;14(4):19–38.

Halkitis P, Parsons J, Stirratt M. A double epidemic: crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. J Homosex. 2001;41(2):17–36.

Parsons J, Halkitis P, Bimbi D. Club drug use among young adults frequenting dance clubs and other social venues in New York City. J Child Adoles Subst. 2006;15(3):1–14.

Purcell DW, Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Mizuno Y, Woods WJ. Substance use and sexual transmission risk behavior of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(1–2):185–200.

Brown J. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: findings from an event-level study. Addict Behav. 2007;32(12):2940–52.

Catania J, Stall R, Paul J, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96(11):1589–601.

Celentano DD, Valleroy LA, Sifakis F, et al. Associations between substance use and sexual risk among very young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(4):265–71.

Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(10):1002–12.

Cooke R, Clark D. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(3):156–64.

Irwin TW, Morgenstern J, Parsons JT, Wainberg M, Labouvie E. Alcohol and sexual HIV risk behavior among problem drinking men who have sex with men: an event level analysis of timeline followback data. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):299–307.

Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20(5):731–9.

Parsons JT, Kutnick AH, Halkitis PN, Punzalan JC, Carbonari JP. Sexual risk behaviors and substance use among alcohol abusing HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Psychactive Drugs. 2005;37(1):27.

Wells BE, Kelly BC, Golub SA, Grov C, Parsons JT. Patterns of alcohol consumption and sexual behavior among young adults in nightclubs. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2010;36(1):39–45.

Wilton L. Correlates of substance abuse use in relation to sexual behavior in black gay and bisexual men: implications for HIV prevention. J Black Psychol. 2008;34(1):70–93.

Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. A model of sexual risk behaviors among young gay and bisexual men: longitudinal associations of mental health, substance abuse, sexual abuse, and the coming-out process. AIDS Edu Prev. 2006;18(5):444–60.

Frost DM, Parsons JT, Nanin JE. Stigma, concealment and symptoms of depression as explanations for sexually transmitted infections among gay men. J Health Psychol. 2007;12(4):636–40.

Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Erickson SJ. Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychol. 2008;27(4):455–62.

Safren SA, Reisner SL, Herrick A, Mimiaga MJ, Stall RD. Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. J AIDS. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S74–7.

Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):37–45.

Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, et al. Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk–taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE study. JAIDS. 2009;51(3):340–8.

Mustanski B. The influence of state and trait affect on HIV risk behaviors: a daily diary study of MSM. Health Psychol. 2007;26(5):618.

Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–42.

Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Mayer KH. Stressful or traumatic life events, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and HIV sexual risk taking among men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2009;21(12):1481–9.

Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, et al. Clinically significant depressive symptoms as a risk factor for HIV infection among black MSM in Massachusetts. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):798–810.

Hart TA, Heimberg RG. Social anxiety as a risk factor for unprotected intercourse among gay and bisexual male youth. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(4):505–12.

Pachankis JE. Developing an evidence-based treatment to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. (in press).

Chiasson M, Parsons J, Tesoriero J, Carballo-Dieguez A, Hirshfield S, Remien R. HIV behavioral research online. J Urban Health. 2006;83:73–85.

Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, Rietmeijer C. HIV prevention and care in the digital age. J AIDS. 2010;55:S94–7.

Sullivan PS, Grey JA, Rosser BRS. Emerging technologies for HIV prevention for MSM: what we have learned, and ways forward. J AIDS. 2013;63:S102–7.

Young SD, Cumberland WG, Lee S-J, Jaganath D, Szekeres G, Coates T. Social Networking Technologies as an Emerging Tool for HIV PreventionA Cluster Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):318–24.

Ybarra M, Bull S. Current trends in Internet-and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):201–7.

Garofalo R, Herrick A, Mustanski B, Donenberg G. Tip of the Iceberg: young men who have sex with men, the internet, and HIV risk. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1113–7.

McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. Young adults on the Internet: risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases and HIV. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(1):11–6.

Mustanski B, Lyons T, Garcia SC. Internet use and sexual health of young men who have sex with men: a mixed-methods study. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(2):289–300.

Wilkerson JM, Smolenski DJ, Horvath KJ, Danilenko GP. Simon Rosser B. Online and offline sexual health-seeking patterns of HIV-negative men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1362–70.

Rosser BRS, Wilkerson JM, Smolenski DJ, et al. The Future of Internet-Based HIV Prevention: a Report on Key Findings from the Men’s INTernet (MINTS-I, II) Sex Studies. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:91–100.

McFarlane M, Bull S, Rietmeijer C. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA. 2000;284(4):443.

Allison S, Bauermeister JA, Bull S, et al. The intersection of youth, technology, and new media with sexual health: moving the research agenda forward. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):207–12.

Buhi ER, Cook RL, Marhefka SL, et al. Does the Internet represent a sexual health risk environment for young people? Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(1):55–8.

Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Social media and young adults. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2010. http://www.pewinternet.org/2010/02/03/social-media-and-young-adults/. Accessed 24 Sept 2014.

Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, et al. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):38–67.

Krehely J. How to close the LGBT health disparities gap. Cent Am Prog. 2009. http://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2009/12/pdf/lgbt_health_disparities.pdf. Accessed 24 Sept 2014.

Hooper S, Rosser B, Horvath K, Oakes J, Danilenko G. An online needs assessment of a virtual community: what men who use the Internet to seek sex with men want in Internet-based HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(6):867–75.

Bowen A, Williams M, Daniel C, Clayton S. Internet based HIV prevention research targeting rural MSM: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. J Behav Med. 2008;31(6):463–77.

Kok G, Harterink P, Vriens P, de Zwart O, Hospers H. The gay cruise: developing a theory-and evidence-based Internet HIV-prevention intervention. Sex Res Social Policy. 2006;3(2):52–67.

Rosser SBR, Oakes MJ, Konstan J, et al. Reducing HIV risk behavior of men who have sex with men through persuasive computing: results of the Men’s Internet Study (MINTS-II). AIDS. 2010;24(13):2099–107.

Chiasson MA, Shaw FS, Humberstone M, Hirshfield S, Hartel D. Increased HIV disclosure three months after an online video intervention for men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS Care. 2009;21(9):1081–9.

Noar SM, Black HG, Piece LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:107–15.

Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Monahan C, Gratzer B, Andrews R. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an online HIV prevention program for diverse young men who have sex with men: the keep it up! intervention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2999–3012.

Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, Joseph H, et al. An online randomized controlled trial evaluating HIV prevention digital media interventions for men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46252.

Rhodes SD, Vissman AT, Stowers J, et al. A CBPR partnership increases HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM): outcome findings from a pilot test of the CyBER/testing internet intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(3):311–20.

Pachankis JE, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Golub SA, Parsons JT. Developing an online health intervention for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2986–98.

Velasquez MM, von Sternberg K, Johnson DH, Green C, Carbonari JP, Parsons JT. Reducing sexual risk behaviors and alcohol use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psych. 2009;77(4):657–67.

Bien T, Miller W, Tonigan J. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88(3):315–35.

Bellack A, DiClemente C. Treating substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(1):75.

Emmons K, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):68–74.

Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara F. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96(12):1725–42.

Lundahl B, Burke B. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clinic Psychol. 2009;65(11):1232–45.

Morgenstern J, Irwin T, Parsons JT, Wainberg M, Bux D. Cognitive behavioral risk reduction intervention versus MET for HIV- MSM with alcohol disorders. In: Working Group of NIAAA Grantees in the Prevention of HIV/AIDS. Bethesda; 2005.

Parsons JT. Positive Choices-an MET intervention for HIV+ MSM with alcohol disorders. In: Working Group of NIAAA Grantees in the Prevention of HIV/AIDS. Bethesda; 2005.

Morgenstern J, Irwin T, Wainberg M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men who have sex with men. J Consult Clin Psych. 2007;75(1):72–84.

Martell C, Safren S, Prince S. Cognitive-behavioral therapies with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. New York: Guilford Press; 2004.

Sobell L, Sobell M. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Assessing alcohol problems: a guide for clinicians and researchers, 5. Darby: Diane Publishing; 1995. p. 55–76.

Sobell M, Sobell L. Problem drinkers: Guided self-change treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

Biener L, Abrams D. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10:360–5.

Slavet J, Stein L, Colby S, et al. The Marijuana Ladder: measuring motivation to change marijuana use in incacertated adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2006;83:42–8.

Fisher W, Fisher J. A general social psychological model for changing AIDS risk behavior. In: Pryor JB, Reeder GD, editors. The social psychology of HIV infection. Hillside: Lawrence Erbaum Associates; 1993. p. 127–53.

Fisher W, Fisher J, Harman J. The information–motivation–behavioral skills model: A general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In: Wallston JSKA, editor. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Victoria: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.; 2003. p. 82–106.

Kiene S, Barta W. A brief individualized computer-delivered sexual risk reduction intervention increases HIV/AIDS preventive behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):404–10.

Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell T, Freitas T, McFarlin S, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psych. 2000;68(1):134–44.

Carey M, Carey K, Maisto S, Gordon C, Weinhardt L. Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(6):365–75.

Weinhardt L, Carey M, Maisto S, Carey K, Cohen M, Wickramasinghe S. Reliability of the timeline follow-back sexual behavior interview. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(1):25–30.

Morgenstern J, Bux D Jr, Parsons J, Hagman B, Wainberg M, Irwin T. Randomized trial to reduce club drug use and HIV risk behaviors among men who have sex with men. J Consult Clin Psych. 2009;77(4):645–56.

Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, Garcia SC, Grov C. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res. 2011;48(2):218–53.

Kalichman SC, Picciano JF, Roffman RA. Motivation to reduce HIV risk behaviors in the context of the information, motivation and behavioral skills (IMB) model of HIV prevention. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(5):680–9.

Lelutiu-Weinberger C. Drug knowledge questionnaire. Unpublished scale. 2011.

Vanable P, Brown J, Carey M, Bostwick R. Sexual health knowledge questionnaire for HIV+ MSM. In: Fisher T, Davis C, Yarber W, Davis S, editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge; 2013. p. 680.

Parsons J, Halkitis P, Bimbi D, Borkowski T. Perceptions of the benefits and costs associated with condom use and unprotected sex among late adolescent college students. J Adolesc. 2000;23(4):377–91.

Wells BE, Golub SA, Parsons JT. An integrated theoretical approach to substance use and risky sexual behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2010;15(3):509–20.

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29.

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605.

Fisher WA, Fisher JD. A general social psychological model for changing AIDS risk behavior. In: Reeder GD, Pryor JB, editors. The social psychology of HIV infection Hillsdale. NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. p. 127–53.

Miller WR, C’de Baca J, Matthews DB, Wilbourne PL. Personal values card sort. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico; 2001.

Sullivan PS, Carballo-Diéguez A, Coates T, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):388–99.

Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, et al. A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. JAIDS. 2005;39(2):228–41.

Huebner DM, Davis MC, Nemeroff CJ, Aiken LS. The impact of internalized homophobia on HIV preventive interventions. Am J Commun Pyschol. 2002;30(3):327–48.

Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Gamarel KE, Golub SA, Parsons JT. Race-based differentials of the impact of mental health and stigma on HIV risk among young gay and bisexual men. Health Psychol. under review.

Kingdon MJ, Storholm ED, Halkitis PN, et al. Targeting HIV prevention messaging to a new generation of gay, bisexual, and other young men who have sex with men. J Health Commun. 2013;18(3):325–42.

Pedrana A, Hellard M, Gold J, et al. Queer as F** k: reaching and engaging gay men in sexual health promotion through social networking sites. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e25.

Bull SS, Levine DK, Black SR, Schmiege SJ, Santelli J. Social media–delivered sexual health intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):467–74.

Donker T, Petrie K, Proudfoot J, Clarke J, Birch M-R, Christensen H. Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(11):e247.

Boulos MN, Wheeler S, Tavares C, Jones R. How smartphones are changing the face of mobile and participatory healthcare: an overview, with example from eCAALYX. Biomed Eng Online. 2011;10(1):24.

Acknowledgments

The MiCHAT Project was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R03-DA031607, Corina Lelutiu-Weinberger, Principal Investigator). The authors acknowledge the contributions of the MiCHAT Project Team—Michael Adams, Alex Brousset, Chris Cruz, Javauni Forrest, Joshua Guthals, Chris Hietikko, Catherine Holder, Ruben Jimenez, Jonathan Lassiter, Drew Mullane, and Matthew Robinson. We also gratefully acknowledge Richard Jenkins for his support of the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lelutiu-Weinberger, C., Pachankis, J.E., Gamarel, K.E. et al. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Efficacy of a Live-Chat Social Media Intervention to Reduce HIV Risk Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS Behav 19, 1214–1227 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0911-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0911-z