Abstract

This paper reflects on the impacts of agrarian change and social reorganisation on gender-nature relations through the lens of an indigenous group named the Kuruma in South India. Building upon recent work of feminist political ecology, I uncover a number of dualisms attached to the gender-nature nexus and put forward that gender roles are constituted by social relations which need to be analysed with regard to the transformative potential of gender-nature relations. Three main themes are at the centre of the empirical inquiry: gender subjectivities, rural off-farm employment and the human-nature nexus. I seek to show that, first, the production of gendered subjectivities cannot be simplified through essentialist assumptions that romanticise women’s relationships with nature; second, off-farm employment strategies both reinforce the social hierarchy in gender and contradict the Kuruma’s moral economies; and, finally, environmental and agrarian change redefine the use of agrobiodiversity and are related to ideas on progressive versus nonprogressive cultivation practices. The research is informed by qualitative research methods and offers a conceptual approach to the deconstruction of gender-nature relations from a poststructuralist feminist perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dualisms attached to the gender–nature relationship often produce an image of women being closer to nature than men. When I worked with an Indian Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) in 2010, the catchphrase “pro nature—pro women—pro poor” offered me inspiration for critical engagement with the gender-nature nexus in South India. Since 1998, the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation’s Community Agrobiodiversity Centre in Wayanad, Kerala has been promoting biodiversity conservation in agriculture by saving endangered rice varieties in the region. Researchers and environmental activists working for the NGO claim that loss of agrobiodiversity in rice systems is directly related to loss of women’s social status as well, which negatively affects indigenous female farmers in particular. Consequently, under the assumption that loss of agrobiodiversity and loss of women’s social status are intertwined, the NGO’s sustainable community development agenda now aims to implement more gender-sensitive use and management of agrobiodiversity (MSSRF 2003).

In this paper, I use the “pro nature—pro women—pro poor” catchphrase as a point of departure for exploring the research questions of how the social reorganization and agrarian change amongst the Kuruma in Wayanad impact gender–nature relations. I put forth the argument that this catchphrase discursively produces a relationship between women and nature that needs to be examined critically as, through it, poor women are seen as victims of changing environmental conditions, indicating that women’s agricultural knowledge and agrobiodiversity need to be protected in order to sustain nature. This idea not only reinforces an essentialist assumption of women as being closer to nature but also portrays marginalised, poor women as protectors of agrobiodiversity. I suggest that these viewpoints require a feminist analysis that critically engages the complexities of gender–nature relations.

The danger of romanticizing indigenous knowledge in India is a key issue raised by a number of feminist thinkers whose work aims to contextualise local knowledge and the management of natural resources (Agarwal 1992; Gururani 2002; Jewitt 2000; Kelkar 2007; Krishna 2007). Jewitt (2000), for example, focuses on examining naturalised assumptions regarding gendered knowledge formation while de-romanticising women’s agroecological expertise in Jharkand, India. Other work is concerned with the essentializing nature of engendering environmental knowledge fostered by Women, Environment and Development (WED) approaches. Kelkar (2007) points towards the interrelations of caste, class, religion and gender which are crucial for identifying “situated gendered actors”. In Gururani’s (2002) view, gender dynamics are culturally defined via sets of ideas and values regarding women and men, especially as they differ in age, class, and ethnicity. In these studies, the notion of situated knowledge is a crucial element for assessing women’s knowledge as embedded in sets of relations produced and based on uneven power dynamics. However, the deconstruction of gender as an analytical category in India “has been located at the bottom of the hierarchy and marginalised” (Krishna 2007: 501), consequently remaining a field of inquiry which has been rarely addressed from a feminist viewpoint.

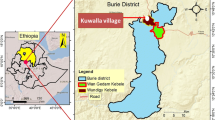

In the present paper, I seek to address this research gap while exploring gender–nature relations from an intersectional feminist political ecology viewpoint. Here I specifically ask how agrarian change and social reorganization are reshaping human-nature-relations amongst the Kuruma people, an indigenous population group in Wayanad, Kerala, India. My findings are based on empirical fieldwork informed by qualitative research methods and conducted from 2010 to 2012 in two indigenous agricultural communities in Wayanad. Crucial in this regard is the notion of doing gender while doing nature (see editor’s introduction in this issue), which builds upon a deconstructionist approach in which gender and nature are taken as socially constructed analytical categories. In order to understand the complex dynamics of gender–nature relations, an analysis of the interrelations between power, women’s agency and subjectivities is needed. In doing this, I aim to highlight the often ambivalent and contradictory meanings of gender–nature relations in the case of the Kuruma.

Background

Research area

India is currently facing an agricultural crisis that demands new policies (Lerche 2011; Narasimha Reddy and Mishra 2009) in order to overcome the low profitability of agriculture (Dhas 2009) which is negatively affecting rural population groups. In Kerala, the agricultural crisis can also be seen as being tied to a political–ecological crisis, leading to increased rural diversification (Arun 2012; Narasimha Reddy and Mishra 2009) and a higher incidence of farmer suicide,Footnote 1 which can be interpreted as a failure of the Indian state to look after its peasants in a globalised world (Muenster 2012).

The interrelations between the agricultural and political–ecological crises taking place in India are also affecting Wayanad, a mountain plateau district of Kerala state, bordering the Western Ghats in South India. The area is characterised by low geographical relief, with 113,000 hectares of agricultural land, of which 1853 hectares are uncultivable. Subsistence crops cover 16,756 hectares and cash crops 65,469. Wayanad district contributes overproportionally to the foreign exchange rates of the state through cash cropping, including pepper, cardamom, coffee, tea, ginger, turmeric, rubber and areca nut (Anil Kumar et al. 2010). Regarding the peoples inhabiting the region, Adivasi is an umbrella term used to refer to indigenous groups, who are also referred to as tribals in India (Rath 2006). The Adivasi have traditionally been involved in small-scale agriculture, mainly paddy cultivation (see Schöley and Padmanabhan and Suma and Grossmann in this issue).

Wayanad is undergoing the kinds of major changes in land use associated with changing agricultural practices from crop to cash farming. Furthermore, due to the low economic profitability of agriculture and increasing demand for agricultural land for real estate and infrastructural development, the cultivation of rice in the region is constantly declining (Nagabhatla and Anil Kumar 2013). Socially, these changes as well as out-migration, thwarted personal aspirations, indebtedness, weakened family relations and alcoholism have been linked to an increasing rate of farmer suicides (Muenster 2012). Ecologically, the region faces another challenge: declining biodiversity of rice landraces due to conversion to other sorts (Anil Kumar et al. 2010). According to Kuruma farmers in Wayanad, irregular rainfall patterns and water scarcity are also exacerbating the problems facing small-scale agriculture in the region (Kunze and Momsen 2015).

The present paper mainly seeks to reflect on the impacts of such agrarian change and social reorganization on gender–nature relations, as seen from the Kuruma perspective. I take the example of a rural off-farm employment program—the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA)—to examine the ways in which this ongoing change is not only gendered but is reshaping gender–nature relations among the Kuruma. As the Kuruma belong to the land-owning AdivasiFootnote 2 groups in Wayanad whose sources of subsistence are rice and vegetables, paddy cultivation thus has an especially strong cultural meaning for them, because rice is their main staple food and is essential to maintaining food security (ibid.). As landholders, they still grow and seek to conserve traditional rice varieties, such as Gandhakasala, which are seen as being central to sustaining Kuruma culture, traditions and consumption habits. However, as I have been describing, ongoing changes in land use and cultivation practices, including conversion of agricultural fields to land for housing and infrastructural development, are redefining gender–nature relations among the Kuruma.

The social organization of the Kuruma people

Exploring the changing gender–nature relations amongst the Kuruma, which have been strongly shaped and redefined by changes in social organization that have been taking place over the last 20 years, demands a closer examination of social roles and their meanings. Here, social organization refers to the family structures existing in the two distinct Kuruma settlements in the subdistricts of Panamaram and Kanjambetta, with a focus on how these have changed from joint to nuclear family structures over time (Betz et al. 2014). Family systems are closely related to social roles, here being defined as structurally given conditions, such as the norms, taboos, expectations, and responsibilities, linked to a given social position in a community. A joint family system in India is almost always dominated by male members, which means that women usually play a subordinate role (Chakrapani and Vijaya Kumar 1994). The relatively recent shift in family system structure amongst the Kuruma has led to a reorganization of property rights, from collective to individual ownership of land. Furthermore, unlike a joint family system, a nuclear family household is often characterised by a more balanced relationship between men and women (see Suma and Grossmann in this volume). This shift in property rights is reshaping gender relations among Kuruma married couples today, as they now tend to both decide over which crops and vegetables are to be cultivated. Thus, the transition from joint to nuclear family systems over the past 20 years has also changed the ways in which gender and related social roles constitute each other.

My conducted fieldwork in the two Kuruma communities in Panamaram and Kanjambetta has revealed how such social and agrarian transformations are mutually linked and are directly influencing social organization at the community level. The social reorganization discussed in this paper refers to changes in education, labour structure and mobility. All these factors, particularly changing labour structures, are affecting cultivation trends because, with growing involvement in off-farm labour, women’s capacities for engaging in family agriculture and performing their normal domestic duties are becoming more limited.

Conceptual framing: theorizing gender–nature relations

Understanding gender–nature relations from a feminist point of view requires the aid of three distinct theoretical strands: ecofeminism, new feminist political ecologies and the moral economy of the peasant.

Ecofeminism

Most feminist scholars describe ecofeminism as an umbrella term linking different approaches to environmental analysis by integrating a number of environmental perspectives (Mies and Shiva 1998; Shiva 1988; Plumwood 1993; Seager 1993). In India, ecofeminism is strongly influenced by Vandana Shiva (1988), who proposes a natural connection between women and environmental resources through which rural, indigenous women are often portrayed as the rightful caretakers of nature. However, the taken-as-a-given but actually socially constructed “feminine principle” in gender–nature relationships that Shiva relies on has been strongly critiqued by various feminist scholars, as it not only essentializes but reinforces dualisms between men/women, culture/nature, indigenous/non-indigenous, body/mind (Agarwal 1992; Jewitt 2000; Krishna 1998; Rometsch and Padmanabhan 2013).

New feminist political ecologies

The feminist political ecology framework provides useful ways for examining issues of resource-access control as well as gendered constructions of knowledge (Bhavnani et al. 2003; Elmhirst and Resurreccion 2008; Momsen 2009; Rocheleau et al. 1996). However, a more specific understanding of Indian contributions to political ecology is offered by Williams and Mawdsley (2006), which presents a useful example of how the traditional/modern binary is reproduced in India from a postcolonial political ecology perspective. Their work deconstructs the division posited by environmental discourses in India between the unsustainable resource usage of elites and threatened livelihoods of ecosystem people due to conflicts over natural resources. In their view, the ecosystem approach to indigenous peoples bears the danger of essentialism, as it embraces the indigenous as the traditional and ends up supporting the traditional/modern binary, which itself has been put into question.

Research inspired by new feminist political ecologies focus on co-constructions of both gender and nature and the ways in which both are socially constructed (Bauriedl 2010). Thus, nature is understood as a socially posited concept which is culturally and historically defined, whereas subjectivity refers to the idea of how people embrace and enact their roles in society (Nightingale 2012). Gender relations can be described as socially constructed forms of relations between women and men. From this perspective, the category of gender is understood as a critical variable in shaping processes of environmental change, livelihoods and visions for sustainable development (Elmhirst and Resurreccion 2008). Furthermore, influenced by poststructuralist theories of subjectivity, new feminist political ecologies explore performance of masculinities and femininities and how these shape gendered subjects through peoples’ everyday practices (Elmhirst 2011, 2015). Viewing gendered performance as a process and gendered subjectivities as social constructions challenges essentialist and binary views of gender relations.

The moral economy of the peasant

The moral economy of the peasant provides a useful theoretical understanding into what is considered to be morally unreasonable or unacceptable economic behaviour from a peasant perspective (Scott 1976; Evers and Schrader 1994; Brocheux 1983). Key to the economics of subsistence that guides peasant life is the safety-first principle, which is tied to the risk-avoidance principle, as peasants focus on the need for reliable forms of subsistence. Crucial in this regard is consideration of the relationships peasants have with their neighbours, elites and the state, looked at in terms of whether these networks aid or hinder them.

Taking into consideration insights from ecofeminism and new feminist political ecologies provides a perspective from which to analyse gender–nature relations; also including ideas derived from the moral economy of the peasantry approach further enriches the analytical approach used in this paper to better understand commodification of off-farm agricultural employment from a peasant standpoint. The next section provides background information about the research area: geographical location, research participants and current social-ecological changes that it is undergoing.

Methods

Qualitative research methods require multiple conceptual approaches and methods of inquiry focused on social processes, individual experiences and human environments (Crang 2003; Bryman 2008; Moss 2002; Winchester 2000). For the present research, two main phases of data collection were conducted in 2011 and 2012, with the unit of analysis being the household level within two Kuruma communities from two different subdistricts: the Kalluvayal and Kanjambetta settlements. Field site collection was based on random choice; my criteria for selecting participants included approachability, accessibility, openness and willingness to take part in the research along with the presence of ongoing social reorganization within their community. The latter was explored by asking both female and male farmers about significant changes in their family systems, gender relations, employment structures, cultivation practices and land use. They were usually interviewed separated by gender, in order to support female participation in the research.

The applied qualitative research methods were similar to those commonly used in other areas of the social sciences (Bryman 2008). Data was mainly gathered through semi-structured and open-ended interviews, which allowed for a flexible interview process. The analysis being presented here draws upon 57 transcribed interviews, including four small-group informant interviews (one female farmer, one male NGO activist and two female tribal promoters), 40 in-depth semi-structured interviews (15 married couples, 20 single women, four single men and one interview with a mother and her son) and 13 focus-group discussions, of which nine were among women and four among men. Recruitment was based on a snowballing sampling, with informed consent being obtained from all participants. Overall, 47 out of 93 households living in the selected communities were sampled. Interviews were conducted with the help of two female research assistants, who transcribed and translated the raw linguistic material into English. Atlas.ti was used to categorize the text into key codes used for analysis.

Having introduced the theories and methods used to inform this case study, the following section lays out the empirical findings. Three main themes are at the centre of the analysis: gender subjectivities, rural off-farm employment and the gender–nature nexus.

Findings

Gendered subjectivities

In this subsection, I put forward that changing agrarian relations and social transformation processes are reshaping gender–nature relations in Wayanad by redefining gender relations at the household level. In the following, I separately discuss the ways in which these process have differently affected women’s and men’s subjectivities in the Kuruma communities studied, though there are unavoidable areas of overlap as well.

Women’s subjectivities

The portrait of women’s subjectivities in the study area developed primarily through the interviews and reveals interrelations between education, mobility, perceptions of nature and employment. Crossing domestic boundaries is seen by the women interviewed as a positive change towards women’s emancipation. Compared to the joint family system, most Kuruma female participants explained that greater mobility today enables women to move beyond the domestic sphere, and the shift from joint to nuclear family settings appears to be favouring such social change. Women from both Kuruma communities stressed a link between education, off-farm labour and mobility, as all influence each other. Improved education is helping tribal women to overcome their inferiority complex and, therefore, has led to them having greater confidence and willingness to participate in public life. Crossing beyond the confines of the domestic domain has also offered tribal women more freedom to socialise with people outside their communities. One reason for the increasing mobility of both women and men in the area is greater accessibility to improved infrastructure, such as newly constructed roads.

As improved education allows women to take part in public life and to generate additional income outside the domestic sphere, most participants consider education to be the main driver for positive change towards empowerment of women within the newly emerging social organization of the Kuruma. Mostly elderly women offered a historical comparison of women’s roles in Kuruma society in the past and present. Whereas the past was characterised by social isolation of tribal communities in Wayanad, Kuruma people do currently interact with people from different caste groups. Earlier, women’s space was restricted to the home and agricultural fields, whereas today many women have crossed out of the domestic domain and are participating in the MGNREGA employment scheme and in women’s self-help groups (Devika and Thampi 2007). In their view, these governmental programmes have increased the variety and status of women’s responsibilities in the tribal household and at the community level. A senior widow stated that, in the past, women usually obeyed what men said but, today, “most of them [the women] are educated” and, therefore, “are engaged in many things and they are learning new things”. This change in gender performance is seen as a positive one by most of the women participants, because it is associated with increased power and independence in decision-making on the household level. The following quotation from a female farmer highlights the changing interrelations within the social reorganization of the Kuruma:

In the past, when it was the joint family system, it was the men who did everything, took all the decisions and mingled with the rest of society. The women at that time were denied all this. But now everything has changed: everyone is educated, so even the women are having jobs and, since they are educated, they can understand what is happening around them without anybody’s help. And also, they are now mingling with other people in the society. So all this has changed their lives.

Not only women are benefitting from improved education, however, as men are also recognising the new opportunities offered through the changes taking place in the social organization of Kuruma communities. As a result of improved education, women not only have greater authority in domestic decision-making processes but also a heightened responsibility to generate additional income for the family (Kunze and Momsen 2015). This new situation is redefining gendered roles and responsibilities among the Kuruma, and the women especially view education as the key towards their integration into the other society, meaning the wider sphere of non-Adivasi people. However, social networking and exchange among their own kind still appears to be particularly important for Kuruma women as well.

Kuruma women appear to be generally against a rigid and socially defined gendered division of labour in contemporary Kuruma society, due to recent changes resulting from what is known as the commodification of labour. Unlike in the past, when the Kuruma were able to trade in kind, more money is required to buy things today, so ensuring a constant income for their families has become crucial for maintaining their livelihoods. With the increasing involvement of women working outside the domestic realm, such as under the MGNREGA, men appear to feel less pressured to solely generate income for their families. Furthermore, farmer suicide rates have gone down, as women’s incomes seem to be helping to take care of their families’ financial needs, thus improving the outlook on life for their male members. This change in labour structure constitutes one major social change that has been resulting in greater gender equality among married couples. Because the MGNREGA offers equal payment for women and men, women feel fairly treated, which also results in greater confidence regarding their social status in the community. Furthermore, unlike the past, when Kuruma women usually did not cross domestic boundaries, participation in the MGNREGA also expands women’s mobility, because work is now often offered outside their communities.

Further, community interaction and embodiment are redefining women’s subjectivities among the Kuruma. Earlier, women used to wear traditional clothing, which is now being replaced by a contemporary mainstream dress code. This shift in embodied performance among Kuruma women is resulting in a feeling of social affiliation with women from other communities and is, consequently, challenging the dualism in bodily performance between Adivasi and non-Adivasi women in the Wayanad context. In addition, interaction between communities is also fostering greater social exchange, with Kuruma people, for example, attending religious functions and festivals taking place in other religious communities.

Yet, according to many Kuruma women, environmental knowledge and agricultural practices are still perceived to be men’s responsibility, which reinforces the formal/informal knowledge binary, a dichotomy based on the idea that “women are not aware about the climate or the environment, because men are more involved in agriculture than women”. In addition, “it is the men who know the methods and techniques […] and about seeds, their maturity and when to plant and harvest” (also see Schöley and Padmanabhan in this issue). Such statements by Kuruma women illustrate that, for them, agriculture is still categorized as a masculine knowledge domain. From this perspective, women only assist men in cultivation, which is then taken as an explanation for why women are not able to claim knowledge in this area.

Men’s subjectivities

Unlike women, whose subjectivities are presently being redefined through increased mobility, education and ongoing social reorganization, men’s subjectivities are still shaped by the notion of being “traditional agriculturalists”. Men at the age of 40–50 are reinforcing the existing socially constructed image of the Kuruma being ecosystem people, while building upon the traditional/modern cultivation practices dualism. From an emic point of view, one male Kuruma farmer argues that, “our case is different, communities like the Kuruma […] are really doing paddy cultivation but other community people do cultivation for their benefits and they keep on changing crops according to their benefit”. This perspective can be said to reveal how masculine identity among the Kuruma is being reproduced as maintaining tradition and being associated with “good” farming practices. Another male farmer, who received an eco-farmer award from the local government, provides interesting insights into his understanding of the very idea of traditional farming:

Traditional farmers know the soil well and they have a close relationship with soil. The traditional farming helps to protect the soil as well as the creatures in it. The modern farming is looking only for profit. […] Traditional farming is good.

This view portrays the dualism between traditional and modern cultivation practices. The traditional way of doing agriculture is constructed as good and environmentally friendly, whereas modern agricultural practices are considered to be only profit-oriented and, therefore, “bad” for the farmers and the environment. Furthermore, the good/bad dualism invoked here can also be linked to sustainability. Traditional farming is related to a sustainable farming approach, while modern farming is considered to be unsustainable. Another male Kuruma farmer describes the notion of traditional agriculture as follows:

We are traditional agriculturalists and, if you observe, you will find people like us doing paddy cultivation. Other people cultivate crops which are only a benefit for them. But we are not like that and, since we are traditional paddy cultivators, we cultivate paddy for own consumption, and we don’t do it for business purposes. For business purposes, people use chemical fertilizers and look for higher yields, and they sell it, and this is their aim of cultivation. But our case is different.

This thought nicely demonstrates the Adivasi/other dualism which distinguishes the traditional Kuruma from other farmers who do agriculture based on economically driven values, leading them, unlike the Kuruma, to use agrochemicals for better yields. This view on traditional agriculture also stresses the cultural meaning and value of growing rice for family consumption needs in order to sustain food security. Additionally, traditional farming is linked to the cultivation of old rice varieties crucial for maintaining the idea of consuming culture on special occasions and community events, such as festivals and weddings. These Kuruma farmers seem, then, to be constructing a “tribal” identity defined through being traditional agriculturalists who feel a need to protect their cultural heritage of cultivating rice—of traditional varieties and applying traditional methods—to meet the needs of their communities in the future.

Comparing women’s and men’s subjectivities with regard to the use and management of biodiversity in agriculture, the data presented from the interviews suggests that it is especially male farmers who want to maintain a traditional agricultural identify. Furthermore, Kuruma men’s perceptions on traditional agriculture appear to be related to the notion of ecosystem people, which reinforces the traditional versus modern dualism (Williams and Mawdsley 2006). Yet, at the same time, the importance of upholding and reproducing a traditional farming subjectivity also seems to be in accord with Scott’s (Scott 1976) safety-first principle, as continuance of rice cultivation also secures consumption needs which are based on rice being the most important staple food in Kerala.

Rural non-farm employment

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA)

As we have seen, reorganization of the Kuruma social system and changing environmental conditions have been impacting agricultural labour structures among them. Crucial in this regard is the MGNREGA, also commonly known as the NREGA, which was enacted by the Ministry of Rural Development of the Indian government in 2005 (Government of India 2013). Meant to improve livelihood security for people in rural areas by securing income for agricultural labourers outside peak seasons, the Act guarantees 100 days of payment for a daily wage rate of Rs. 120 for semi-skilled and unskilled laborers working in public works areas such as building road connectivity, flood control, water conservation and harvesting, drought proofing as well as micro-irrigation structures in villages (Jose and Padmanabhan 2015). In order to participate in the program, participants need to register officially and must have a bank account. In Wayanad, 66% of the total indigenous population is registered, some of whom also hold landed property, which in effect reduces the overall availability of labor for rice cultivation (ibid.).

Research has revealed that the introduction of MGNREGA has enhanced the socio-economic condition of socially disadvantaged groups, including landless laborers, scheduled castes/tribes and small marginalized farmers in rural areas. However, a lack of awareness-building campaigns regarding the program’s entitlements, social inclusion and good governance, to name only a few important issues, remains an institutional weakness to be addressed in the future (Haque 2011). In addition, a gendered analysis of the Act indicates that the program has had virtually no impact on the social transformation of women’s needs, though it potentially does support women’s empowerment (Pellissery and Jalan 2011).

The impacts of the MGNREGA on gender relations among the Kuruma who have informed this study appear to be ambivalent. Participation in the program—which attracts mainly single and uneducated people between 30 and 50 years old—is clearly gendered as today, it is mostly women who join because it provides opportunities for generating income, involving both agricultural and non-agricultural work. In Wayanad, in fact, female participation constitutes 95% of all MNREGA workers (Thadathil and Mohandas 2012). The main driver for women to participate in this rural employment program is the prospect of increased financial independence, given the guaranteed wage each month.

One can observe a shift towards greater appreciation of economic values in a nuclear-family setting, emphasising the need for both women and men to generate income. A male farmer, for example, explains that, through the MGNREGA

[w]omen and men have equal responsibilities and there is no division of labour work. Women today do all kind of work that men do. […] Men and women get equal wages in MGNREGA, and if we go for work outside we will get more wages, so we prefer doing work outside than going for MGNREGA work. For women, that wage is enough. […] If we [men] don’t have any other work outside, then we go for MGNREGA.

This male perspective on the Act seems to not only reflect but also reinforce the existing gendered social hierarchy. Further, it stresses that, unlike women, men have better options for generating income with better conditions than those offered through the MGNREGA. Women are perceived as co-earners, though men continue to follow the breadwinner model of acting as the family member who earns the most and takes economic decisions. As the quoted farmer perceives men like himself to be higher in the social hierarchy than women, he also feels entitled to receive better pay when possible. Today, accepting MGNREGA work appears, then, to constitute a female livelihood strategy, as men usually do not aim for it, given the low payment of Rs. 150 a day under the Act compared to an average daily wage rate for male paddy laborers of Rs. 250 (Thadathil and Mohandas 2012). This reveals existing gender differences in the labor market and shows that men have more opportunities to find better-paid daily wage work than women, particularly when the latter are less educated. Masculine work is also characterized by more physically strenuous tasks, such as carrying wood or stones used for construction and housing, a booming sector.

Kuruma moral economies

Aside from the positive impacts of the MGNREGA on the gendered division of labour—offering better income strategies for women and increasing their mobility—the program also needs to be subjected to critique, especially as the rules and regulations of the MGNREGA offer little long-term security towards fulfilling many of their everyday needs. Particularly for young mothers, the Act offers no options for generating additional household income, which might be a necessity for them due to logistical reasons, such as inability to undertake long commutes and lack of childcare possibilities during work hours. The program also conflicts with the Kuruma’s moral economy in terms of strategies of timing and resource pooling, because wages are only paid on a monthly basis, which makes it difficult to meet daily expenses for people who have not been used to having savings. Furthermore, given the limited work opportunities outside the agricultural season and a maximum of 100 working days, senior women critique how the Act fails to offer women economic stability.

Taking an activist feminist perspective, the NGO Women’s Voices in Wayanad has critically reflected upon the MGNREGA, which is viewed as constituting a governmental programme that, in effect, further reinforces the uneven power relations between women and men in the region. According to the NGO, the standard minimum-wage policy of the programme rather exploits than empowers women’s social and economic roles. Based on the NGO’s experience, Adivasis do not have the habit of saving money for the future, because they tend to spend it the same day that they get it. Furthermore, landless Adivasis and those who have difficulties getting an identity card required for MGNREGA registration are excluded from the Act. Hence, instead of reducing the social and economic vulnerability of marginalised groups like the Adivasis, the employment act rather takes advantage of marginalised people because, in exchange for their low-paid and temporary labour, it offers them little in terms of long-term livelihood security, as also mentioned by the Kuruma women cited in the previous subsection. This standpoint offers an interesting perspective on the exploitative aspects of the MGNREGA as being associated with an on-going marginalization of tribal people in Indian society.

Criticism of this rural work programme is also relevant for understanding tribal politics and the ways in which social hierarchies define people’s social status within Indian society. According to my Kuruma informants, participation in the MNGREGA differs according to class, caste and religion (Thadathil and Mohandas 2012). It is in fact middle-class people, mostly Christian women and older people, who tend to make use of this work opportunity. Particularly for seniors, the MGNREGA provides a strategy for generating additional income. From the Kuruma point of view, however, the Act might not necessarily provide the best future prospects for the poor, because when tribal people participate in the MNREGA, they are automatically re-categorized onto the Above Poverty Line (APL) list. Given the benefits offered by the government when registered on the Below Poverty Line (BPL) list—such as health insurance coverage or allowances for housing—tribal people often refrain from participating in the work programme, as it ultimately leads to a devaluation of their economic standing. This situation is a likely cause of the ambivalent opinions related to the MGNREGA and seems to undermine the government’s idea of enhancing social protection through public works (Pellissery and Jalan 2011).

Gender–nature nexus

A changing environment

Overall, agrarian change and changing environmental conditions, including increasing temperatures, irregular rainfall and water scarcity, appear to be negatively affecting gender–nature relations in the study area. These factors have also been shaping a wider agrarian crisis (Lerche 2011) which is characterised by the altering of cultivation practices from subsistence staples (rice) to cash crops (plantains, beans, ginger), due to the low economic profitability of rice today. Water is a key environmental concern in the region and is, naturally, closely related to agriculture.

A dominant theme for both male and female Kuruma farmers with regard to their knowledge of the agro-ecosystem is deforestation and lack of water. Deforestation has not only changed the physical landscape but also the ecosystem, resulting in increasing water scarcity. Lack of water is also strongly related to the current trend of conversion from food to cash crops, such as the introduction of areca nut (Jose and Padmanabhan 2015). Irregular rainfall poses a major challenge to paddy cultivation in particular because, unlike plantains and bananas, rice relies upon natural rainfall.

Male and female Kuruma farmers emphasise that water scarcity, irregular rainfall, infrastructural development as well as population growth are all negatively influencing the future of agriculture in their communities. Senior female farmers in particular stress the unpredictable patterns of rainfall that negatively affect the cultivation of rice in particular and the environment more generally. Despite the growing uncertainty of the future of agriculture, farmers of both genders all argue for a need to sustain paddy cultivation in order to maintain food security. This perspective reinforces the fact that agriculture is not only based on cultural but also on economic values, as being able to cultivate rice minimizes economic expenses and avoids financial risk according to the logic and ethics of subsistence production. One senior female farmer who works on her family’s fields suggests that environmental issues and obstacles to agriculture such as drought, erosion and flooding need to be overcome, because the Kuruma still feel the need to continue with agriculture while adapting to the changing environmental conditions. Adaptation can thus be seen as one strategy for trying to ensure subsistence production (Scott 1976) and, thereby, sustaining food security in the community. Furthermore, despite the changing environmental conditions they are facing, female and male farmers all underline the cultural value of rice. For example, one female farmer points out that “whatever happens, we won’t avoid cultivating paddy—at least for own consumption”. A male farmer adds that rice “is the most important food item for the Kuruma, and it is important to cultivate what we consume”. Buying rice from the outside would be too costly, contradicting the logic of the subsistence principle. Key for the continuance of paddy cultivation and home-grown rice is ownership or availability of agricultural land. However, some farmers reveal counter-tendencies to this perspective, complaining about the diminishing lack of interest shown by the young generation in agriculture, due to an increased orientation toward profitability. This lack of agreement within the farming community highlights a direct link between agrarian and social transformation processes taking place amongst the Kuruma farmers and in the Wayanad region in general. Furthermore, my fieldwork has revealed age to be an important factor for gaining a better understanding of the multiple dimensions of agrarian change, because it is particularly young Kuruma women who now show little interest in agriculture in Wayanad.

Another crucial factor reshaping gender–nature relations among the Kuruma is tourism. A male Kuruma farmer, referring to the growing real estate and tourism industries, explains:

Now tourism is spreading very fast, so the real estate business is thriving and so the value of land has gone up. This is a major problem for the tribal people. So, in these places, land use has drastically changed. One example is Kuruva Island nearby. Earlier it was all pristine forest and good water, but now there are so much anti-social elements. The water is very much polluted and the environment is not very safe. There are broken beer bottles everywhere. It is not safe to walk in the water anymore. […] We are not saying that tourism is bad and that tourists are unwelcome, but there should be a limit, and the rules and regulations should be strictly followed. (emphasis added)

Interesting is the dualism between social and anti-social relationships to nature, because it underlines the “ills of development” (Williams and Mawdsley 2006) and how they disturb the natural landscape while “exploiting nature”. One solution, or possibly a more “social” approach, offered by the Kuruma to maintaining a sustainable balance with the environment would be state intervention based on legal agreements that would seek to protect the natural landscape. Furthermore, female informants emphasised the need for infrastructural development as being crucial for sustaining agriculture in Wayanad.

The contradictory values of agrobiodiversity

The decision-making process regarding the growing of traditional rice varieties versus hybrid ones appears to be marked by ambivalence. The old rice variety Gandhakasala, for example, has a strong cultural meaning for the Kuruma and is mainly used for weddings, religious ceremonies and festivals. According to male farmers, the main reasons for a decline in old rice variety cultivation include a growing focus on economic values, meaning here the attempt to achieve high economic benefits from agriculture at the lowest possible expense. One male farmer explains the link between crop maturity and economic profit. A new rice variety, for example, takes two to three months to grow, whereas an old variety requires six months. Therefore, another male farmer describes the old variety as being “not progressive”, emphasising the need for agricultural progress. However, most Kuruma male farmers claim that, instead of only providing subsidies based on a profit-maximising orientation, financial support from the government should be given to maintain the cultural values of doing agriculture in a sustainable manner.

Female Kuruma farmers see the future of agriculture being dependent on environmental change and their capability as farmers to adapt to it. In this vein, it is worth noting that crop preferences are also related to the reliability of agricultural seasons and the availability of water for irrigation. For example, farmer of both genders from the Kanjambetta Kuruma settlement argue that the cultivation of old rice varieties should be seen as a gain because, unlike the new rice varieties, traditional ones are less vulnerable to pests and diseases. Particularly with regard to increasing water scarcity and/or irregular rainfall patterns, the cultivation of traditional rice varieties appears to be more feasible, as these are also more resistant to lack of water. Yet, a farming couple from the Kalluvayal Kuruma settlement has challenged this perspective, clarifying that, due to irregular rainfall patterns and water scarcity, farmers today can only cultivate during one agricultural season as opposed to two in the past. This tends to lead to the selection of those crops that grow easily within one season and require less water. For example, plantains require less water than paddy, though the latter does not require any pesticides or fertilizers.

Overall, the attitude towards agrobiodiversity amongst the Kuruma is contradictory and has multiple meanings in terms of traditional versus modern relations to nature. On the one hand, Kuruma female and male farmers underline the strong cultural importance of growing traditional rice varieties to sustain Kuruma culture and food traditions. On the other hand, the cultural significance of cultivating traditional rice varieties contradicts the increasingly economically driven nature of agriculture in Wayanad. Being a traditional farmer appears to stand in opposition to the idea of being a progressive one. In addition, changing rainfall patterns and the long cultivation period of traditional rice varieties challenge the basis of the Kuruma’s subsistence needs. However, with regard to pest control, the cultivation of traditional rice varieties might actually be a better choice.

Conclusions

In this paper, I have looked at the ways in which agrarian change and social reorganization of two Kuruma communities in Wayanad, India, are reshaping gender–nature relations. In doing so, I have focused on the three main themes gendered subjectivities, rural off-farm employment and the gender–nature nexus and identified a number of contradictions revealing the complexities of gender–nature relations.

Taking a careful look at gendered subjectivities in the study area has put under pressure the socially constructed image of women being closer to nature or protectors of agrobiodiversity, which are aspects that actually seem to play an insignificant role in the everyday lives of Kuruma women. Instead, it is rather men who reinforce the dichotomy between traditional/modern agriculture by constructing a self-identity of Kuruma people as being “traditional agriculturalists” who cultivate sustainably in environmental and economic terms. Agriculture is categorized as a masculine domain which not only constitutes social relations of power and authority between female and male Kuruma farmers but also denies women the right to claim agricultural knowledge. Kuruma women’s subjectivities are now, however, being strongly reshaped by social reorganization taking place at the community level, key determinants of which include access to education, mobility and increased employment opportunities.

Meanwhile, a governmental work program, the MGNREGA, is now contributing in a less than ideal manner towards increasing the transformative potential of shifting gender roles among the Kuruma at the household level. On the one hand, the MGNREGA has altered women’s social status in three important ways by, firstly, increasing women’s geographical mobility, secondly, offering women the opportunity to generate additional income for their families and, finally, enlarging women’s economic responsibility within the nuclear-family setting now becoming prevalent. Yet, on the other hand, the employment scheme seems to be reinforcing the traditionally gendered social hierarchy in which men are perceived as the “breadwinners” and women as mere co-earners. This finding contributes to recent work by Quisumbing et al. (2015) highlighting that gender norms limit women´s assets in agricultural interventions. Also, the MGNREGA appears to be in conflict with the Kuruma’s moral economy and its related risk-reduction principle, because the program’s 100-day work offer policy fails to offer long-term economic stability. In addition, the interplay of gender, age, ethnicity, social status, and caste are important intersectional categories of difference that might potentially reinforce gendered inequalities rather than support women’s empowerment through the program. This finding adds to Perkins’s (1993) work on technical and social changes in agriculture during political economic crisis. Thereby, the promotion of intensive agriculture is described as a response to the lack of food self-sufficiency which often conflicts with the very idea of social quality and justice.

Changing environmental conditions, such as irregular rainfall, water scarcity and land-use conversion practices as well as the tourism industry are resulting in an uncertain future for agriculture in the region. Nevertheless, both female and male Kuruma farmers stress the need to sustain old-variety rice cultivation in order to maintain food security and to minimize economic expenses. Some Kuruma farmers also consider tourism to be as an “anti-social” element that is exploiting nature in the region and, therefore, upsetting human–nature relations there.

Contradictory values also seem to be circulating within the Kuruma community regarding agrobiodiversity, specifically with regard to the cultivation of traditional versus modern rice varieties. Some informants in the study area do not consider old rice varieties to be progressive, whereas others argue for their continued cultivation, due to their resistance to pests, diseases and water scarcity. According to most female farmers, the availability of water through irrigation appears to be a crucial concern for sustaining agriculture in the future. Meanwhile, male farmers seem to be more concerned with the shift in values away from subsistence and towards profit-oriented farming. Instead, they argue for more financial support from the government to maintain the cultural values of doing agriculture sustainably, particularly with respect to paddy cultivation. These findings nicely demonstrate the ways in which knowledge systems are understood as multi-leveled structures and characterised as “open” systems that are constantly challenged by shifting formal and informal as well as local and global contexts (Brodt 1999).

How do these findings add to broader discourses on gender and natural resource management concerned with the ways in which social and agrarian change are gendered? The findings of this research of undertaken in South India reveal the need to consider ideas of negotiation and of survival strategies as outlined by work of Valdivia and Gilles (2001). As response to changes in the environment, small-scale Kuruma women and men farmers negotiated over the need to keep the old-variety rice in order to maintain food security on a household level. This can be viewed as a successful negotiation over the use of agrobiodiversity that aims at enhanced family well-being and the sustainable use of old-variety paddy seeds. The analysis of the rural employment programme (MGNREGA) provides examples for a successful negotiation amongst rural families as the participation is linked to an improved social status of Kuruma women. However, the analysis also highlights outcomes of unsuccessful negotiations of the MGNREGA programme because it interferes with small-farming moral economy and expands women´s economic responsibilities on a household level that might reduce the family well-being.

The use of the feminist political ecology framework appeared to be useful to analyse the interplay of agrarian change and the social reorganisation. Inspiring work in this regard is offered by Finnis (2007) who uses actor-oriented analysis that puts small-farm experiences at the centre of inquiry and aims towards a better recognition and incorporation of small-farmers experiences, voices and priorities. Considering actor network theory and supply chain management theory, referring to Jarosz’s (2000) idea of specific geographies of networks may further enrich conceptual approaches to map social-agrarian transitions.

Returning to the catchphrase with which I have tried to encapsulates the motivation underlying this paper, I conclude that, instead of simplifying gender–nature relations in terms of “pro nature—pro women—pro poor”, it is rather the complex dualisms of traditional/modern agriculture, formal/informal agricultural knowledge, progressive/anti-progressive methods as well as social/anti-social practices that are shaping the Kuruma’s relationships with their environment today.

Notes

Muenster’s (2012) ethnographic study on the political ecology of farmer suicides in the agrarian district of Wayanad reveals that they are linked to two trends: firstly, to specific practices of cash crop farming and to the regional history of the political–ecological crisis and, secondly, to biographies of migration, personal aspirations, choking debts, problematic family relations and possibly to diseases and alcoholism.

My fieldwork from 2010 to 2012 has revealed that is usually Kuruma men who own and inherit agricultural land. Once a woman is married, she usually uses her husband’s fields for cultivation. Meanwhile, unmarried women work on the fields of their parents or extended family members.

References

Agarwal, B. 1992. The gender and environment debate: Lessons from India. Feminist Studies 18(1): 119–159.

Anil Kumar, N.P., G. Gopi, and P. Prajeesh. 2010. Genetic erosion and degradation of ecosystem services in wetland rice fields: A case study from Western Ghats, India. In Agriculture, biodiversity and markets: Livelihoods and agroecology in comparative perspective, ed. S. Lockie, and D. Carpenter, 137–153. London: Earthscan.

Arun, S. 2012. ‘We are Farmers too’: Agrarian change and gendered livelihoods in Kerala, South India. Journal of Gender Studies 21(3): 271–284.

Bauriedl, S. 2010. Erkenntnisse der Geschlechterforschung für eine erweiterte sozialwissenschaftliche Klimaforschung. In Geschlechterverhältnisse, Raumstrukturen, Ortsbeziehungen: Erkundungen von Vielfalt und Differenz im spatial turn, ed. S. Bauriedl, M. Schier, and A. Strüver, 194–216. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Betz, L., I. Kunze, P. Prajeesh, T.R. Suma, and M. Padmanabhan. 2014. The social–ecological web: A bridging concept for transdisciplinary research. Current Science 10(4): 572–579.

Bhavnani, K.-K., J. Foran, P.A. Kurian, and D. Munshi (eds.). 2003. Feminist futures: Reimagining women, culture and development. London: Zed Books.

Brocheux, P. 1983. Moral economy or political economy? The peasants are always rational. The Journal of Asian Studies 42(4): 791–803.

Brodt, S.B. 1999. Interactions of formal and informal knowledge systems in village-based tree management in central India. Agriculture and Human Values 16(4): 355–363.

Bryman, A. 2008. Social research methods, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chakrapani, C., and S. Vijaya Kumar (eds.). 1994. Changing status and role of women in Indian society. New Delhi: MD Publications.

Crang, M. 2003. Qualitative methods: Touchy, feely, look-see? Progress in Human Geography 27(4): 494–504.

Devika, J., and B.V. Thampi. 2007. Between ‘Empowerment’ and ‘Liberation’: The Kudumbashree initiative in Kerala. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 14(1): 33–60.

Dhas, A. C. 2009. Agricultural crisis in India: The root cause and consequences. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/18930/. Accessed 8 March 2015.

Elmhirst, R., and B. Resurreccion (eds.). 2008. Gender and natural resource management. London: Earthscan.

Elmhirst, R. 2011. Introducing new feminist political ecologies. Geoforum 42(2): 129–132.

Elmhirst, R. 2015. Feminist political ecology. In The Routledge handbook of gender and development, eds. A. Coles, L. Gray and J. Momsen, 58–66. Routledge handbooks. London: Routledge.

Evers, H.-D., and H. Schrader. 1994. The moral economy of trade: Ethnicity and developing markets. London: Routledge.

Finnis, E. 2007. The political ecology of dietary transitions: Changing production and consumption patterns in the Kolli Hills, India. Agriculture and Human Values 24(3): 343–353.

Government of India. 2013. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005. http://nrega.nic.in. Accessed 8 March 2015.

Gururani, S. 2002. Construction of third world women’s knowledge in the development discourse. International Social Sciences Journal 54(173): 313–323.

Haque, T. 2011. Socio-economic impact of implementation of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in India. Social Change 41(3): 445–471. doi:10.1177/004908571104100307.

Jarosz, L. 2000. Understanding agri-food networks as social relations. Agriculture and Human Values 17(3): 279–283.

Jewitt, S. 2000. Unequal knowledges in Jharkhand, India: De-romanticizing women’s agroecological expertise. Development and Change 31(5): 961–985.

Jose, M., and M. Padmanabhan. 2015. Dynamics of agricultural land use change in Kerala: A policy and social-ecological perspective. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 14(3): 307–324.

Kelkar, M. 2007. Local knowledge and natural resource management: A gender perspective. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 14(2): 295–306.

Krishna, S. (ed.). 1998. Gender and biodiversity management. Gender dimensions in biodiversity management. Delhi: Konark.

Krishna, S. 2007. feminist perspectives and the struggle to transform the disciplines: Report of the IAWS Southern Regional Workshop. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 14(3): 499–514.

Kunze, I., and J. Momsen. 2015. Exploring gendered rural spaces of agrobiodiversity management—A case study from Kerala, India. In The Routledge handbook of gender and development, eds. A. Coles, L. Gray and J. Momsen, 106–116. Routledge handbooks. London: Routledge.

Lerche, J. 2011. Agrarian crisis and agrarian questions in India. Review essay. Journal of Agrarian Change 11(1): 104–118.

Mies, M., and V. Shiva. 1998. Ecofeminism. Melbourne: Spinifex Press.

Momsen, J. 2009. Gender and development. London: Routledge.

Moss, P. (ed.). 2002. Feminist geography in practice: Research and methods. Malden: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

MSSRF—The M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation. 2003. Farmers’ rights and biodiversity: A gender and community perspective. Chennai: MSSRF.

Muenster, D. 2012. Farmers’ suicides and the state in India: Conceptual and ethnographic notes from Wayanad, Kerala. Contributions to Indian Sociology 46(1–2): 181–208.

Nagabhatla, N., and N.P. Anil Kumar. 2013. Developing a joint understanding of agrobiodiversity and land-use change. In Cultivate diversity! A handbook on transdisciplinary approaches to agrobiodiversity research, ed. A. Christinck, and M. Padmanabhan, 27–51. Weikersheim: Margraf Publishers.

Narasimha Reddy, D., and S. Mishra. 2009. Agrarian crisis in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Nightingale, A.J. 2012. The embodiment of nature: Fishing, emotion, and the politics of environmental values. In Human-environment relations: Transformative values in theory and practice, ed. E. Brady, and P. Phemister, 135–147. London: Springer.

Quisumbing, A.R., D. Rubin, C. Manfre, E. Waithanji, M. van den Bold, D. Olney, N. Johnson, and R. Meinzen-Dick. 2015. Gender, assets, and market-oriented agriculture: learning from high-value crop and livestock projects in Africa and Asia. Agriculture and Human Values 32(4): 705–725.

Pellissery, S., and S.K. Jalan. 2011. Towards transformative social protection: A gendered analysis of the employment guarantee act of India (MGNREGA). Gender & Development 19(2): 283–294.

Perkins, J.H. 1993. Cuba, Mexico, and India: Technical and social changes in agriculture during political economic crisis. Agriculture and Human Values 10(3): 75–90.

Plumwood, V. 1993. Feminism and the mastery of nature. London: Routledge.

Rath, G.C. (ed.). 2006. Tribal development in India: The contemporary debate. New Delhi: Sage.

Rocheleau, D., B. Thomas-Slayer, and E. Wangari (eds.). 1996. Feminist political ecology: Global issues and local experiences. London: Routledge.

Rometsch, J., and M. Padmanabhan. 2013. Vandana Shiva: Kämpferin für das, Gute Leben‘oder rückwärtsgewandte Konservative? Ariadne 64: 40–47.

Scott, J.C. 1976. The moral economy of the peasant: Rebellion and subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Seager, J. 1993. Earth follies: Feminism, politics and the environment. London: Earthscan.

Shiva, V. 1988. Staying alive: Women, ecology and survival in India. New Delhi: Kali for Women.

Thadathil, M.S., and V. Mohandas. 2012. Impact of MGNREGS on labour supply to agricultural sector of Wayanad District in Kerala. Agricultural Economics Research Review 25(1): 151–155.

Valdivia, C., and J. Gilles. 2001. Gender and resource management: Households and groups, strategies and transitions. Agriculture and Human Values 18(1): 5–9.

Williams, G., and E. Mawdsley. 2006. India’s evolving political ecologies. In Colonial and post-colonial geographies of India, ed. S. Raju, M. Satish Kumar, and S. Corbridge, 261–278. New Delhi: Sage.

Winchester, H.P.M. 2000. Qualitative research and its place in human geography. In Qualitative research methods in human geography, ed. I. Hay, 1–22. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kunze, I. Dualisms shaping human-nature relations: discovering the multiple meanings of social-ecological change in Wayanad. Agric Hum Values 34, 983–994 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9760-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9760-x