Abstract

Amidst expanding interest in local food and agriculture, food banks and allied organizations across the United States have increasingly engaged in diverse gleaning, gardening, and farming activities. Some of these programs reinforce food banks’ traditional role in distributing surplus commodities, and most extend food banks’ reliance on middle class volunteers and charitable donations. But some gleaning and especially gardening and farming programs seek to build poor people’s and communities’ capacity to meet more of their own food needs, signaling new roles for some food banks in promoting community food security and food justice. This article reports the results of a national survey and in-depth case studies of the ways in which food banks are engaging in and with local agriculture and how this influences food banks’ roles in community and regional food systems. The patterns it reveals reflect broader tensions in debates about hunger relief and food security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Food relief goes local—so what?

Building off expanding interest in local food and agriculture, in recent years food banksFootnote 1 across the United States have increasingly engaged in gleaning,Footnote 2 gardening, and farming. Journalists and hunger relief professionals have touted these programs as innovative departures from food banks’ traditional distribution of canned and boxed commodities (Harris 2005; Bratton 2008; Zezima 2008; Evans and Clarke 2011; Santos 2011; Weise 2011). But are food banks’ links and involvement in local agriculture really transforming the overall quality of food they distribute? And to what extent do these diverse gleaning, gardening, and farming activities signal new roles for food banks in community and regional food systems? Are these programs changing food banks’ relationships with poor people in their cities and regions? Or are gleaning, gardening, and farming programs perpetuating the ironies and inequities of the emergency food system, for which scholars and activists have widely critiqued food banking?

In 2011–2013, we conducted a national survey and fifteen in-depth case studies documenting patterns and practices of gleaning, gardening, and farming by and for food banks in the United States. Recording how much food these programs were yielding provided a basic measure of how, and how many, food banks are gaining a large share of food from these sources. Visiting and interviewing the people who run these programs allowed us to explore their motivations, relationships with constituencies, and other questions related to their aims and operations. In this article, we first review scholars’ and advocates’ critiques of food banking, then discuss our findings, and finally consider their political and practical implications for food banks’ roles in community food systems.Footnote 3

Our findings suggest that food banks’ gleaning, gardening, and farming programs are alternately challenging and reinforcing longstanding patterns of food relief. Most of the local produce obtained through these programs effectively constitutes additional commodity surplus. This enables some food banks to distribute more diverse and nutritionally healthier foods as well as increase the total quantity of food distributed. These programs change food banks’ relationships with their suppliers, but not so much with the recipients of their food. Most gleaning, gardening, and farming programs perpetuate food banks’ reliance on middle class volunteers and charitable donations. However, some food banks are playing new and expanded roles in building community food security and promoting food justice, especially through programs that invest in building poor people’s capacity to garden and farm (and cook) themselves. This represents a significant departure from most food banks’ traditional missions, operations, and politics. It suggests various ways that hunger relief systems have the potential to promote community food security more broadly.

Food banks and community food security

Scholars and activists concerned with community food security often celebrate strategies that deploy local agriculture to help feed and revitalize poor communities, but rarely cast food banks as the drivers of this or other positive changes. Rather, many have condemned food banks for the roles they play in community food systems and the broader food system. Food banks’ gleaning, gardening, and farming programs challenge some of these critiques and assumptions, though they reinforce others.

Janet Poppendieck’s critique of food banking in Sweet Charity (1999) has largely defined critical food studies and community food security practitioners’ perspectives on food banks. Exposing the “seven deadly ‘ins’” of “emergency food”—its insufficiency, inappropriateness, nutritional inadequacy, instability, inaccessibility, inefficiency, and indignity—Poppendieck (1999) argued that not only did food banks distribute a bad mix of foods, but they also did it in ways that reinforced the inequities and injustices of the food system and society. By subsidizing mainly processed, boxed, and canned commodity producers for their mistakes (mainly over-supply or mislabeled goods), the emergency food system benefits big industry and the poverty-industrial complex of nonprofits at least as much as it does poor people. Moreover, in a much-echoed critique, Poppendieck (1994, 1999) examined how food banks’ reliance on upper income volunteers reinforces public acceptance, even celebration, of a system that casts the poor as dependent and passive recipients of charity and diverts attention from more fundamental solutions to hunger and poverty (see also Allen 1999; Fisher and Gottlieb 1995; Guthman 2011; Tarasuk and Eakin 2005; Winne 2008). As Mark Winne (2007) emphasized, “there is something in the food-banking culture and its relationship with donors that dampens the desire to empower the poor and take a more muscular, public stand against hunger.”

The commodity surplus distribution system that food banks largely coordinate appears to fundamentally contradict Hamm and Bellows’ classic definition of community food security as a “condition in which all community residents obtain a safe, culturally acceptable, nutritionally adequate diet through a sustainable food system that maximizes community self-reliance, social justice, and democratic decision-making” (2003: 37).Footnote 4 Defining food assistance “as that which the corporate sector cannot retail” effectively precludes the food and social system—and in practice also the diet—envisioned by community food security advocates (Tarasuk and Eakin 2005: 177). Even distributing local produce from big industry ties food banks to the “conventionalizing, scale-inducing, structural inequity” of the industrial food system, which “easily morphs” local food “into a commodity” (DeLind 2011: 277). As long as food banks are synonymous with distribution of surplus commodities, it is easy to cast their work as antithetical to maximizing justice, democracy, and de-commoditization.

Food studies scholars and activists on the left regularly acknowledge food banks as part of the food security “safety net”; and community food security advocates generally support linking sustainable agriculture and fighting hunger. But rarely are food banks characterized as engines of community food security and justice (see Allen 1999; Allen et al. 2003; Feenstra 1997; Fisher and Gottlieb 1995; Gottlieb and Joshi 2010; Hamm and Bellows 2003; Levkoe 2006; Poppendieck 1999; Wells et al. 1999; Winne et al. 1997; Winne 2008). Beyond arguments for a stronger welfare state and more equitable distribution of income and wealth, advocates commonly focus on smaller organizations such as community kitchens, gardens, farms, and food centers owned and operated by poor people building food sovereignty.

But is it time for community food security advocates to embrace or at least explore if food banks can be potential engines of the changes we want to see in community food systems? Have food banks’ local agriculture programs begun to effectively answer some of our critiques? Have the fruits and vegetables they yield substantially changed the mix of food that food banks distribute, and the ways this food is produced, distributed, and consumed? More profoundly, are gleaning, gardening, and farming programs enabling food banks to transcend their traditional roles as distributors of surplus commodities? Are they changing food banks’ relationships with middle class volunteers and, most importantly, with people who are poor and hungry? Ultimately, are these programs promoting community food security and justice?

There is little literature on food banks’ local agriculture programs. Some case study research has examined gleaning programs, often using ethnographic methods to examine how they operate (Evans and Clarke 2011; Hoisington et al. 2001; Molnar et al. 2001). Some scholars have explored their dependence on middle class volunteers (Poppendieck 1994, 1999; Tarasuk and Eakin 2005). But researchers have not yet documented nationwide patterns in food banks’ involvement with local agriculture, nor have researchers assessed the impacts and implications of various types of gleaning, gardening, and farming programs.

We sought to capture these broad patterns as well as the ways in which these programs are departing from food banks’ traditional roles to promoting community food security in more meaningful ways. In our assessment of these programs, we operationalize the goals and standards of community food security—maximizing self-reliance, justice, and democracy—in terms of the ways in which food programs build poor individuals’ and communities’ capacity to meet more of their own food needs. Poor people’s active participation in these programs—as growers, harvesters, distributors, and chefs, beyond being recipients of handouts—was one key variable by which we assessed them (though we did not measure the quality of anyone’s participation). We also noted whether programs were investing in (1) building individual human capacities, for example in people’s food production, processing, preparation, consumption, or other life or job skills; and (2) the physical infrastructure of disadvantaged communities’ food systems, for instance via support of home and community gardeners, seed banks, and farms.

Methods

We chose to study food banks (as opposed to cupboards or other small organizations) because they present opportunities to consider how hunger relief systems can be transformed at a large scale, that of the city, region, or nation. Food banks’ methods of counting the food they distribute are also standardized, though their ability to tally the food in their local agriculture programs varies greatly. We defined “local” as food produced in programs run by food banks or food sourced directly from producers in food banks’ own region or state (and in some cases adjacent states). We focused on fruits and vegetables, though many food banks distribute local venison donated by hunters and some (mainly in Texas) have distributed meats from industrial processors.

The programs we identified and included in our universe constitute the main ways food banks attain produce from local agriculture. They are:

-

Gleaning: Volunteers, nonprofit staff, or farm workers harvest vegetables and fruit that farmers or gardeners do not want, in the field or sometimes from farmers markets. This food is distributed to food banks, member cupboards and feeding programs, and sometimes to volunteers who do the picking.

-

Grow-a-row: Gardeners or farmers plant and harvest rows, plots, or fields of vegetables for donation to food banks, member cupboards, and feeding programs.

-

Garden support programs: Food banks support community, school, and home gardeners in poor and middle class communities, providing education, materials such as seedlings and soil, as well as outlets for donated produce.

-

Gardens and farms: Food banks often have gardens at their facilities and sometimes own farms. Staff and volunteers tend and harvest these sites, some of which include gardener and new farmer training programs.Footnote 5

-

Direct sourcing: Some food banks contract with farmers for single crops or to supply a mix of food for weekly distribution to food banks or directly to low-income households.

Although we did not count them in our tally of programs and food, we also documented how some food banks process, preserve, and prepare food that they grow or glean, typically in their own kitchens and sometimes in the context of cooking education and food service worker training programs.

Our research consisted of two parts: (1) a national survey of gleaning, gardening, and farming programs run by, or that worked directly with, food banks, and were active in 2011; and (2) in-depth case studies that included site visits to 15 organizations and in-person interviews with 27 staff members at those organizations (mainly executive directors and program directors).Footnote 6

The national survey consisted of web-based research and follow-up emails and phone calls to food banks, in three stages. First, we reviewed the 2011 directory of Feeding America, the trade association that includes most of the larger food banks in the United States (202 in 2011), identifying food banks that reported their garden, farm, or gleaning programs. Additionally, we screened the websites of the remaining members of Feeding America to identify additional food banks with such programs that had not been captured in the directory. Our second phase involved working with our partner organization, SHARE Food Program, and Hunger Free Pennsylvania to identify additional food banks that were not affiliated with Feeding America. The third phase consisted of a snowball sample, developed by asking each individual we contacted at food banks and their partners about other programs we had not yet identified.

We collected standardized information via Internet review, email surveys and/or telephone calls to all food banks noted to have farming, gardening, or gleaning programs. That basic information included:

-

1.

Confirmation that the program(s) existed;

-

2.

Characteristics and types of gleaning, gardening, and farming programs;

-

3.

Number of pounds of local produce yielded or distributed in 2011;

-

4.

The total amount of food distributed by the food bank that year.

This data supports our analysis of national patterns of production and distribution. Ample room for error exists both in our identification of food bank programs and in food banks’ tallies of produce from these programs. However, the food banking sector’s standardization of how food banks count pounds of food and other information they report for reimbursement from federal and state food programs, and to Feeding America, helps control for this error.

For the in-depth case studies, we selected a sample of twelve food banks and three nonprofit gleaning organizations that distribute to food banks. In choosing cases, we sought a wide range of gardening, gleaning, and farming programs in different regions of the U.S., with different operations as well as local climates and agricultural bases. They provide a diverse, fairly representative cross-section of programs in terms of geography, size, and type of local agriculture work. Site visits involved in-depth interviews with multiple staff, visits to local farms, gardens, and gleaning sites, and participation in some gleaning and gardening activities.

Our interviews examined the history and operations of each program. We asked about how each program works, including details of the production and distribution chain. We asked about the program’s mission, participants, and outputs, among other questions. We also asked if the leaders of those food banks were aware of other food banks’ local agriculture initiatives as well as their own plans and ideas for the future. The paragraphs that follow provide an overview of the patterns from the national survey and then the details of the case studies and other programs we found.

National patterns

We identified 115 organizations with relevant programs in the U.S.—90 food banks, nine state associations of food banks, and 16 other nonprofit organizations. These organizations altogether run 73 gleaning programs, 65 gardening programs, and 21 programs operating or partnering with farms. Almost half of the members of Feeding America were involved in local agricultural programs in some capacity, as were other smaller, non-member food banks.

In total, the programs we identified tallied more than 274 million pounds of local fruit and vegetable production and distribution in 2011, but most of the volume was concentrated in a small number of food banks. At most food banks, produce that comes directly from local farms and gardens accounts for a small proportion of the total food they distribute, typically about one percent. However, we found seventeen food banks that grew and sourced over five percent (and thirteen of those over ten percent) of their total food directly from local agriculture, mostly through large-scale gleaning (Table 1).

By volume, commodity surplus from industrial agriculture dwarfs other sources of local produce distributed by food banks and their member agencies. By far the greatest amounts of fresh fruits and vegetables sourced directly from local growers to food banks—almost 97 percent of the total we counted—are harvested through gleaning programs that distribute millions of pounds. Most of this produce comes from big commercial farms (over half in California) and is picked and packed by their workers. A smaller portion of the total, still millions of pounds, is gleaned by legions of volunteers, often from churches. A small number of food banks also harvest and source large amounts of “first pick” produce from their own and nearby farms. In garden support programs, however, most of the harvest goes unrecorded because only a small proportion is passed through food banks themselves, and when it is counted the amounts tend to be small.

The geography of food banks distributing larger proportions of local produce varies, but certain patterns emerge. Food banks in affluent suburbs in Chester County, Pennsylvania, West Chester and Long Island, New York, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Food Gatherers), and Santa Clara/San Mateo (Silicon Valley) and Orange County, California, have combined gleaning, gardening, and farming programs to make local fruits and vegetables between 13 and 50 percent of all the food they distribute to the relatively small proportion of area residents in poverty. Yet wealthy communities are not the only ones to achieve such high percentages, as food banks in poorer cities and rural regions have too, including in Tucson, East Texas, Raleigh, and the Blue Ridge region of Northwest Virginia. (Food banks in Cleveland and Detroit distribute large amounts of produce, though they do not record what proportion is local).

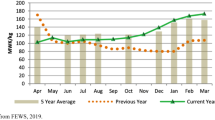

Even among food banks distributing large proportions of fresh local food, the number of pounds of local produce distributed per person receiving food at member agencies fluctuates (as noted in Table 1, the total amounts of food and numbers of recipients vary considerably between food banks). The typically modest amounts of fresh local produce per person in most cases are often distributed unevenly among member agencies, especially to those with greater refrigeration and distribution capacity. Even at the cupboards and other feeding organizations with the greatest amounts of produce, often only some of the people they serve receive these fruits and vegetables. And in every region the seasonality of local agricultural production creates variation across the year.

Over 85 percent of the food banks and allied organizations involved in fresh produce distribution rely upon volunteers donating time or food in some or all of their local agriculture programs, suggesting that most of these initiatives do not challenge or diminish food banks’ dependence on these forms of charity. Mostly middle class volunteers plant, weed, and harvest food banks’ own gardens, participate in grow-a-row donation programs, or glean fields or backyards. Gardening, gleaning, and a few farming programs have created new volunteer opportunities quite different from packing and moving boxes in warehouses, energizing old volunteers and attracting new ones to food banks (or to garden for food banks they never visit). Some people even pay for the experience of gleaning for food banks.

While commodity surplus and middle-class volunteers figured largely in our findings, we also found over 40 food banks that involve and support poor people in growing, processing, preparing, and sometimes selling their own food. These food banks’ and their partners’ investments in programs in which poor people play active roles generally reflect goals that are distinct from their other local agriculture programs.

In interviews, food bank staff reported diverse motivations for starting and expanding their different local agriculture programs. They consistently cited the rise in poverty and demand for food relief since the mid-2000s, and the increasing efficiency and diminishing surplus from industry, as impetuses to seek new sources of food (interviews 1–3, 5–7, 11–20, 25–27). They broadly shared an aim to diversify the mix of foods they distribute beyond canned and boxed commodities, increasing the volume and share of fresh fruits and vegetables, including “the leafy stuff” that is least shelf-stable (interview 6), and thereby promoting healthier diets (interviews 1–8, 11–24). Some food bank staff noted they gained greater control over their supply of food by running their own farms or contracting with farmers (interviews 1–3, 5–7, 9, 12, 14, 22, 25–27).

Other interviews revealed certain food bank leaders’ desire to do more than change the nature of the food they distribute: to alter their relationships with the people they help feed, and to transform the roles their organizations play in community food systems—as one executive director put it, to “go beyond the old business of cans in, cans out” (interview 1). Often, they cast gardening, farming, and some gleaning programs as better positioned than the commodity surplus system to address the roots of hunger. Food bank staff whose gardening and farming programs are aimed centrally at participants from low-wealth communities aspire to support poor people’s skill building to gain greater control over their own food supply. Some also seek to encourage active lifestyles among the poor in their community, school, and home gardening, and some farming and gleaning programs (interviews 1–3, 7, 8, 12–14, 21–26).

The wide range of motivations, operations, and outputs and outcomes in our sample is evident in the cross-section of gleaning, gardening, and farming programs profiled below. Within each of these categories, too, these programs are diverse.

Gleaning

Field gleaning has transformed the mix of foods distributed by an increasing number of food banks. Gleaning is an ancient tradition, a key part of the agricultural poor laws of the Bible. But unlike ancient and feudal traditions in which the poor gleaned farmers’ fields and could decide whether and how to eat, donate, or sell the food, today mostly middle class volunteers and farmworkers do the work of gleaning for food banks. However, some exceptional gleaning programs involve people who receive food assistance in connecting with their sources of food and building their capacity to provide for their own food needs.

While the great majority of food (and of produce) “gleaned,” “recovered,” or “salvaged” for most food banks comes from wholesale terminals and supermarkets, in some parts of the United States field gleaning has scaled up substantially, especially as food banks and their state associations have connected with corporate farms. In 2012, the California Association of Food Banks’ Farm to Family program distributed 127 million pounds of fresh produce to 41 food banks around the state, aggregating donations and paying growers to cover added costs, mainly for packing (see California Association of Food Banks n.d.; 2011). Similar gleaning programs operate in Arizona (18.5 million pounds in 2011), Texas (13 million), Ohio (26 million, though much of this is from wholesalers), and smaller programs in Arkansas (1.2 million), Colorado (1 million), and Kentucky (almost 1 million). More are starting up in other states, inspired by the work of their peers.

Some longer-established volunteer and corporate gleaning programs operate independent of but in partnership with food banks. The Society of St. Andrew, founded in 1983, marshals over 30,000 volunteers annually, 110 per gleaning event, mainly from churches but also from the Boy Scouts and other groups, especially in the Southeast but as far west as the Rockies. In 2011, it distributed almost 27 million pounds of produce, mostly potatoes. Ag Against Hunger, based in Salinas, California, and founded in 1990, aggregates donations from over 50 growers and shippers whose workers glean in the fields and packinghouses. It also organizes teams of volunteers to glean on alternate Saturdays from April through November. It consolidates all this produce at a central cooling facility and then distributes it to food banks—8.4 million pounds in 2011. Ag Against Hunger also trades some of this food with programs in other regions of California and Arizona, to gain a more diverse range of produce across a longer season, a pattern also evident within Arizona, Oregon, and Maryland. These supply chains and the mix of farmworkers and middle class volunteers who harvest the food represent common patterns in gleaning from commercial farms for food banks.

Many food banks run their own gleaning programs, and some of these achieve a large scale of distribution, too. The St. Mary’s Food Bank Alliance in Flagstaff, Arizona, for example, distributed over 7.35 million pounds of produce in 2011, 11.5 percent of all the food it gave out. Much of this came from Arizona’s state program, while St. Mary’s own Citrus Gleaning program registers and picks trees in home gardens, sending the harvest to the Sun Orchards company to make juice that the food bank then distributes.

Most food bank gleaning programs rely on farmworkers and middle class volunteers, but prisoners also figure prominently in some programs. The Association of Arizona Food Banks, Maryland Food Bank, and the Arkansas Hunger Relief Alliance use inmates to glean farmers’ fields. The Arkansas program, which is run in collaboration with the Society of St. Andrew, deploys prisoners as its main source of labor.

Although the large gleaning programs discussed above account for the great majority of produce sourced directly from regional farms to food banks, other gleaning programs run by or tied to food banks operate differently and promote distinct politics of food. Some food banks encourage cupboards and their clients to participate in gleaning, and some connect their member feeding organizations to farmers markets, urban farms, and other sources of fresh, local produce to glean in their neighborhood. Also, individuals across the country have established an increasing number of small nonprofit gleaning organizations that donate their harvest to food banks and member agencies. They glean from farms, community gardens, and especially backyard fruit trees in cities and suburbs.

Neighborhood gleaning organizations that partner with food banks typically deploy middle class volunteers, though in different ways. Village Harvest in San Jose (203,000 pounds in 2011) and the New Orleans Fruit Tree Project (10,000 pounds) recruit volunteers to harvest from willing tree owners’ backyards. Food Forward in Los Angeles (350,000 pounds) began in 2009 by recruiting volunteers from the mainly middle class networks of Craigslist and the local Slow Food chapter. In addition to volunteer “picks,” Food Forward advertises picks for private groups, for a fee, as an alternative to conventional corporate picnics or birthday parties, selling the experience of doing meaningful work in the fields and an optional trip to a food pantry (interview 8).

Some programs that involve poor people in gleaning and processing the harvest promote food justice and community food security more directly and explicitly. The Portland Fruit Tree Project is, in the words of its founder, Katy Kolker, “a unique urban twist on traditional gleaning” (interview 21). The organization reserves half of the volunteer slots in its “harvest parties” for low-income individuals or people living with food insecurity; and its “group harvests” are exclusively for clients of hunger relief organizations with which it partners. People take home half of what they glean, typically about 5 pounds per person, delivering the rest directly to food cupboards; and they also use some of the fruit in food preservation workshops. They gleaned 67,000 pounds in 2012, though the goal of the program is not simply to get fruit into the emergency food system. It also aims to give people the experience of harvesting and preserving their own food, building knowledge and skills for increased self-sufficiency. In addition to gleaning and food preservation, the organization plants community orchards and offers workshops on fruit tree care, aiming to influence other parts of the food chain and community food security (interview 21). These sorts of activities are more common among smaller urban agriculture and community food institutions than among big food banks. Food bank gardening and farming programs more often involve poor people more actively than gleaning programs.

Gardening

Food banks operate and partner with a variety of gardening programs. Most take the form of grow-a-row donation networks among middle class gardeners or food banks’ own gardens tended by middle class volunteers. Yet a growing number of food banks are running community, home, and school garden support programs, often aimed at engaging poor people in producing (and processing, cooking, and eating) their own food. These programs typically yield relatively small amounts of food across a limited growing season, though their goals differ from those of the large-scale gleaning programs that prioritize volume.

Two grow-a-row programs, the Garden Writers of America’s Plant-A-Row for the Hungry and AmpleHarvest.org, link tens of thousands of home and community gardeners in every state to thousands of food cupboards. In 2011, Plant-A-Row tallied over two million pounds of donated vegetables and fruit and AmpleHarvest.org close to fifteen million, dispersed widely in mostly small amounts. Many food banks also run their own grow-a-row programs. Second Harvest of the Inland Northwest in Spokane, Washington, boasts the nation’s largest Plant-A-Row program at a food bank, counting almost 285,000 pounds donated from gardeners, farms, and farmers markets in 2011 (though other food banks typically classify farmers market donations as gleaning instead of “grow-a-row”). This amounted to about 1.7 % of all the pounds of food distributed by the food bank.

Many food banks combine grow-a-row donations with the harvest from their own production gardens, which are typically small. Harvesters Community Food Network in Kansas City, Missouri, has a garden at its warehouse and partners with a network of gardens and garden centers around the city. These sites yielded nearly 40,000 pounds in 2011. This yield is the median average among food bank gardening programs we found (the mean average is 143,000 pounds, much higher due to exceptional yields from some programs).

Demonstration and teaching gardens operated by food banks generally produce less food, but they aim to involve poor people more than most grow-a-row programs and production gardens at food bank warehouses. The Oregon Food Bank in Portland, for example, runs a five-week beginner gardening series for adults with the state extension service and operates two Learning Gardens (one with an adjacent middle school). These gardens yielded 17,000 pounds of fresh produce in 2011, but they supported more home and community garden production by poor people as they distributed seedlings through cupboards and other partner agencies (interviews 19, 20). FOOD for Lane County, across the state in Eugene, runs three growing sites, from which it counted over 75,000 pounds and operated diverse educational and food distribution programs: the 2.5 acre GrassRoots Garden, with a city compost demonstration site, outdoor kitchen, and workshops by food bank staff and master gardeners; a 1-acre community garden where neighbors and students from nearby schools grow and learn about food; and a 3.5 acre youth farm, home to the food bank’s teen job skills program which operates a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program and two produce stands. These programs engage a mix of middle class and poor constituencies; and they build a variety of skills for food production, consumption, and related social, economic, and ecological literacies.

An increasing number of food banks have developed programs offering material as well as technical support to home and community gardeners, mainly in poor communities, at a large scale. The Atlanta Community Food Bank supports over 100 community gardens linked to cupboards and other community organizations. The food bank helps find land and organize neighbors to start gardens, in addition to supplying seeds, tilling, tools, and volunteers for garden maintenance and harvest days. The large Tapestry WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) garden is the only garden where the food bank records the harvest (over 106,000 pounds in 2011). The From the Ground Up program at the Capital Area Food Bank in Washington, D.C., teaches partner agencies’ staff and clients about gardening, sustainability, and food justice (interviews 22, 23). In its first year, 2011, the home gardening program at the Food Bank of Santa Barbara, California, provided some 4,000 people with training and materials. It also started community-based seed banks and a seed library at the food bank’s warehouse.

Some food banks have established gardens with other institutions that serve poor people at a city or countywide scale, including affordable housing and school systems. Food Gatherers in Ann Arbor, Michigan, started community gardens at thirteen affordable housing sites, where it also runs health, nutrition, and leadership programming and a farmers market where some residents sell their harvest. In addition, the food bank operates its own half-acre farm and supports gardens at about thirty churches (interviews 12, 13). The Chester County Food Bank adopted a strategy to transform school food in the poorest districts of Pennsylvania’s wealthiest county through gardening and sourcing and processing locally grown produce. It established gardens and related curriculum at thirty schools and an education center for students, teachers, and the public at the county-owned Springton Manor Farm, where the food bank’s outdoor classroom offers workshops on gardening and nutrition. In the food bank’s well-equipped kitchen, it makes value-added products from the school garden harvests and other locally sourced produce, including dried fruit, soups, tomato sauce, and other foods that are incorporated into a backpack program at schools and daycare centers as well as senior boxes and meals on wheels programs. While Chester County Food Bank’s large sourcing of food from local farms is what enables it to substantially change the food in school cafeterias, its engagement of students and teachers in the entire food chain aims to influence people’s “food skills and literacies” and “the culture of school food” (interviews 1–3).

Farming

Programs that involve food banks in farming or connect them to local farms for more than gleaning are less common and generally newer, compared to gleaning and gardening programs. Some focus on sourcing from local farms. Other food banks have hired staff farmers to run their own farms, sometimes operating youth, refugee, or other workforce development programs, and sometimes supporting community and home gardeners. These programs address a wide range of goals.

A few food banks purchase large amounts of fruits and vegetables from small local producers, often on contract. The Maryland Food Bank contracts with two farms to grow about a dozen acres of the crops which member agencies and their clients demand most, an approach common among food banks contracting with farms. The Lowcountry Food Bank in Charleston, South Carolina, purchases food from small-scale, minority farmers at prices that aim to ensure farmers a decent wage. The leaders of the Chester County Food Bank—in a suburban county with acute development pressures, much sprawl, and an active farmland preservation movement—view the food bank’s contracts with over 40 vegetable, fruit, and dairy farms, coupled with its farm auction purchases, gardening programs, farms, and staff farmer, as investments in the viability and preservation of a rich local agricultural heritage (interviews 1–3, 27).

Links to local fruit and vegetable farmers have inspired changes in the distribution systems of food banks. Some, including Gleaners in Detroit and the Food Bank for New York City in Harlem, have developed CSA programs. These often operate alongside local fruit and vegetable distribution to cupboards, where food banks have invested in cooling equipment to handle perishable produce, and also sale at farmers or mobile markets.

Some exceptional food banks deploy farming to explicitly promote food justice and challenge the traditional culture and systems of food banking. Inter-Faith Food Shuttle in Raleigh, North Carolina, runs two farms and helped start, purchase, and sustain seven community gardens, including growing spaces for recent immigrants and others who have struggled to access land. Its farms and gardens host its Youth Agriculture Training Program, Young Farmer Leadership Program, and a Regional Outreach Training Center run in partnership with Milwaukee’s Growing Power. Inter-Faith connects some of its graduates to the Craft-Up program, in which young farmers intern with experienced farmers, supporting the preservation of small- and mid-scale farming in the region. “Food doesn’t fix the problem” of hunger, says director and co-founder, Jill Staton Bullard, in explaining why the food bank got into gardening, farming, and cooking with people experiencing food insecurity (interview 14).

The Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona in Tucson runs two “community farms” of about three acres each, a program for home gardeners, and a demonstration and market garden. Its farms and garden honor the area’s native peoples through plantings and events, host youth programs that operate farmers markets, and are tied to community organizing, cooking, and nutrition programs at the food bank’s community food center (interviews 24, 25). Similarly, the New Hampshire Food Bank operates three farms, one with a small farm business incubation program for refugees resettled by the food bank’s parent organization, Catholic Charities. Some of the harvest is incorporated into the food bank’s culinary training program. Through these sorts of youth and workforce development programs, some food banks have diversified their community development activities and their roles in the food system.

A new politics of food banking?

The various local agriculture programs discussed above have divergent implications for food banks’ roles in community food systems. Most of the gleaning programs essentially extend the commodity surplus system and often the inequities associated with it. Most of the gleaning and gardening programs reinforce the charitable model of food banking, with its reliance on middle class volunteers and donors. But some gardening, farming, and a few exceptional gleaning programs allow food banks to take on new roles in community food systems, including meaningful investments in promoting food justice and community food security.

Large-scale gleaning programs have dramatically transformed the variety and nutritional quality of the food that some food banks distribute. This alone is an important change. The recent replication of these programs in many states—along with food banks’ adoption of nutrition policies and investments in nutrition education—suggests that many food banks are getting better at promoting dietary health. This, in a sense, constitutes a relatively new and constructive role for food banks.

However, the ways the large gleaning programs attain fruits and vegetables are problematic from a community food security perspective, as they reproduce the familiar inequities of the emergency food system and industrial agriculture more generally. By extending the commodity surplus system to the fields and packinghouses of corporate farms, these programs further enrich big corporations through direct payments and tax write-offs for their donations.Footnote 7 They reproduce the everyday problems of working conditions and wages in industrial agriculture, and in some states they are part of the prison-industrial complex. While some may be tempted to view inmates’ involvement as a restorative act, for both prisoners and the communities they are helping to feed, their work is neither entirely voluntary nor substantially remunerated.

In one of the greatest ironies we found, Arizona’s statewide program gleans blemished produce arriving from Mexico at the Nogales border crossing, taking food grown in a poorer country, often on farms owned by U.S. companies. Food banks then distribute it to poor people in one of the states most invested in restricting poor Latin Americans’ migration to seek opportunities in the U.S. The inequities of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which restricts the movement of people but not goods, thus extend beyond the private market to implicate the food relief system as well.

Neighborhood gleaning programs appear less problematic, though their reliance on middle class volunteers and philanthropy reinforces the charitable mode of food banking and also keeps the means of production and distribution out of the hands of the poor. Some middle class gleaning and gardening programs share the widespread irony in community food programs that often espouse radical politics but resort to charitable models that reproduce inequality. For example, Food Forward originated when its founder, working with migrant workers in California, realized that most farmworkers could not afford the produce they picked. While this origin story rooted in a food justice critique is an important part of the organization’s identity, it operates with middle class volunteers and markets the experience for corporate retreats and school trips in ways that seek to make those volunteers and paying customers feel good about their charity.

The Portland Fruit Tree Project is an important counter-example to the great majority of gleaning programs, as it involves poor people centrally in its work, though it is exceptional and also run by a partner organization, not a food bank itself. In another ironic twist, though, much of its staff is made up of AmeriCorps volunteers making modest stipends, while Food Forward has created full-time jobs with living wages. This reflects broader patterns characteristic of local food and agriculture nonprofits with largely middle class versus poor constituencies.

Most food bank gardening programs, too, reinforce the charitable model of food relief, but those gardening and farming programs principally involving poor people represent an important departure from this. Through programs that provide material, educational, and other technical support for poor people in gardening and farming, food banks are promoting community and household food production, workforce and small business development, and a variety of life skills and literacies. The farmer and culinary worker training programs at some food banks even address the critique of community food security advocates who view employment and increased wages as the true solution to hunger. Ultimately, these gardening and farming programs involving poor people arguably constitute food banks’ greatest investment in building communities’ capacity to meet their own food needs, and the greatest departure from the commodity surplus and charitable systems of food banking.

Gardening also sometimes transforms the roles of middle class volunteers, whose service to the poor takes on new meanings (beyond donating food or money) when it involves teaching in educational programs or informal support of fellow community gardeners. Food bank staff reported that garden support and education are among their most popular programs, often helping catalyze both poor and middle class participants’ deeper involvement in community food systems. These findings are consistent with other research on community gardening and gardeners’ donations to food relief, which has found that growing and distributing food strengthens community capacity and networks of social and economic support, including but beyond food production and distribution (Alaimo et al. 2010; Blair et al. 1991; Feenstra et al. 1999; Helphand and Lawson 2011; Levkoe 2006; Vitiello and Wolf-Powers 2014).

However, it is important to recognize the limits of food banks’ small farming and community, school, and home garden support programs for meeting poor people’s immediate needs and promoting community food security over the long-term. In light of the vast demand for food assistance, these programs are no substitute for commodity surplus programs, volunteer support, and donations. Gardening and farming complements but does not replace most of the canned and boxed starches, proteins, and other calories distributed by food banks. Gardening at a large scale is also not a realistic strategy for all people who experience food insecurity, due to factors ranging from time constraints to land access. Similarly, not every cupboard, homeless shelter, or soup kitchen will be a viable place to garden or farm, depending on their organizational capacity, location, and focus of their work. But many poor people and feeding organizations are good candidates to grow their own food, as illustrated by the larger garden support programs run by food banks.

The variety of food banks’ local agriculture programs also suggests a range of potential policy and system changes, from corporate to charitable to radical. The corporate gleaning programs clearly improve emergency food itself, injecting substantial proportions of fresh fruits and vegetables into federal and state distribution programs; and they could do so beyond the regions where they have already scaled up. Some food banks have set specific targets for the percentage of fresh and local food they distribute, suggesting that state and federal policies and programs could, too. Changing the metrics that matter to food banks (largely pounds distributed) is challenging; however, teaching and supporting poor people to provide for more of their own food needs has potential to play well in political circles where reducing dependency is a priority. Programs profiled above offer examples of how food production and distribution systems can be transformed to provide more healthful, fresh food to poor people, and to grow people’s capacity to cook and eat it, whether or not food banks go beyond the commodity surplus system.

Those gardening and farming programs that promote community food security exist in an unusual but growing political space for food banks. The small amounts of food tallied by these programs help explain why several food bank staff reported finding limited interest in this work among other food banks, especially after answering their questions about how many pounds they generate. Conversely, the same staff, whose programs explicitly promote food justice and sovereignty, noted difficulty in getting community food security advocates excited about their work, due to suspicion of the food banking industry (interviews 26, 29–31). These disconnections and missed opportunities are familiar in the politics of food and hunger (Campbell 2004). Yet the work of an increasing number of programs suggests that a new politics of food banking is possible.

Conclusion

Parsing the various paths taken by food banks’ local agriculture programs reveals a great variety of approaches, politics, and implications for improving the emergency food system. Corporate gleaning programs distribute the greatest amounts of food, but also reproduce familiar ironies and injustices of food relief and industrial agriculture. Gardening programs and neighborhood gleaning expand food banks’ reliance upon middle class charity. But many gardening programs also involve poor participants in meaningful ways, and some explicitly promote food sovereignty and build individual and community capacity. Some food banks have become citywide community and home garden support organizations, managing networks of community gardens and distributing thousands of potted tomatoes and other vegetables through cupboards. Farming and culinary training programs have given food banks even more diverse roles in community and economic development and attendant opportunities to transform food relief systems. While the numbers of pounds of food point to the dominance of the commodity surplus system, particularly in the big statewide gleaning programs, the thousands of gardeners, the smaller number of farmers, and a handful of food justice programs we found illustrate that food banks can assume new roles in community food systems.

These findings suggest that no longer should we exclude food banks from our visions of community food security. But they also indicate that it remains important to be discerning as we assess the outcomes and implications of food banks’ local agriculture work for social justice. Still, the recent growth of gardening, farming, and gleaning programs that involve poor people and promote food justice is a hopeful sign that food banks and the food relief systems they largely orchestrate can become more effective agents of community food security.

Notes

Food banks are nonprofit organizations designated by state governments to distribute federal and state food aid to food cupboards (also known as pantries and sometimes confusingly also called “food banks”), soup kitchens, homeless shelters, and other emergency food and feeding organizations.

In general terms, gleaning refers to the collection of goods that their producers or resellers cannot or choose not to sell. It most commonly refers to the harvesting of crops from farmers’ fields, but also from gardens and other sites.

While this article presents a normative critique of this work, our separate report on this research, aimed largely at food bank staff and related practitioners, includes more detailed quantitative analysis as well as case studies of the programs we visited (Vitiello et al. 2013).

Community food security differs from food security partly in that (1) food security in the U.S. is measured at the household level, while community food security encompasses the larger scale of a community; and (2) community food security is viewed as a process of seeking these goals as well as an end-state.

We distinguish farms and gardens in this paper by whether the food bank calls a site a farm or garden. The main distinction between food banks’ farms and gardens is that most of the farming programs sell some of their harvest, often through farmers markets or mobile markets run by food bank youth or job training programs, whereas the great majority of the gardening programs do not sell their harvest.

Our citations of interviews aim to illustrate the prevalence of certain findings from those interviews, i.e., how many interviewees noted particular things.

Tax write-offs enable corporations and individuals to decrease the amount of taxes they pay to government.

Abbreviations

- CSA:

-

Community-supported agriculture

- WIC:

-

Women, infants, and children

References

Alaimo, K., T.M. Reischl, and J.O. Allen. 2010. Community gardening, neighborhood meetings, and social capital. Journal of Community Psychology 38(4): 497–514.

Allen, P. 1999. Reweaving the food security safety net: Mediating entitlement and entrepreneurship. Agriculture and Human Values 16(2): 117–129.

Allen, P., M. FitzSimmons, M. Goodman, and K. Warner. 2003. Shifting plates in the agrifood landscape: The tectonics of alternative agrifood initiatives in California. Journal of Rural Studies 19(1): 61–75.

Blair, D., C. Giesecke, and S. Sherman. 1991. A dietary, social and economic evaluation of the Philadelphia urban gardening project. Journal of Nutrition Education 23: 161–167.

Bratton, J. 2008. Food banks turn to gleaning in lean times. USA Today (July 22). http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/food/2008-07-21-farmfood_N.htm. Accessed 20 June 2012.

California Association of Food Banks. N.d. Farm to Family Out the Door: A Food Bank’s Guide to Produce Distribution in California. http://www.cafoodbanks.org/farm-family-out-door. Accessed 20 June 2012.

California Association of Food Banks and California Department of Food and Agriculture. 2011. Utilizing New Methods of Crop Harvesting to Introduce Nutrient-Dense Specialty Crops to Low Income Consumers. http://www.cafoodbanks.org/utilizing-new-methods-of-crop-harvesting. Accessed 20 June 2012.

Campbell, M.C. 2004. Building a common table: The role for planning in community food systems. Journal of Planning Education and Research 23(4): 341–355.

DeLind, L.B. 2011. Are local food and the local food movement taking us where we want to go? Or are we hitching our wagons to the wrong stars? Agriculture and Human Values 28(2): 179–194.

Evans, S.H., and P. Clarke. 2011. Disseminating orphan innovations. Stanford Social Innovation Review 2. http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/disseminating_orphan_innovations. Accessed 10 June 2013.

Feenstra, G.W. 1997. Local food systems and sustainable communities. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 12: 28–36.

Feenstra, G.W., S. McGrew, and D. Campbell. 1999. Entrepreneurial community gardens: Growing food, skills, jobs and communities. California: University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication. 21587.

Fisher, A., and R. Gottlieb. 1995. Community food security: Policies for a more sustainable food system in the context of the 1995 Farm Bill and beyond. Working Paper no. 11. The Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies. School of Public Policy and Social Research. Los Angeles: University of California.

Gottlieb, R., and A. Joshi. 2010. Food justice. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Guthman, J. 2011. “If they only knew”: The unbearable whiteness of alternative food. In Cultivating food justice: Race, class, and sustainability, ed. A.H. Aikon, and J. Agyeman, 263–281. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hamm, M.W., and A.C. Bellows. 2003. Community food security and nutrition educators. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 35(1): 37–43.

Harris, W. 2005. Banking on home grown goodness: Community gardens find a food bank niche. Kerr Center Field Notes (summer), 6–8. http://www.kerrcenter.com/nwsltr/2005/summer2005/community_gardens.htm. Accessed 20 June 2012.

Helphand, B., and L. Lawson. 2011. The culture of food and Chicago’s community gardens. Site Lines 6(2): 6–9.

Hoisington, A., S.N. Butkus, S. Garrett, and K. Beerman. 2001. Field gleaning as a tool for addressing food security at the local level: Case study. Journal of Nutrition Education 33(1): 43–48.

Levkoe, C.Z. 2006. Learning democracy through food justice movements. Agriculture and Human Values 23(1): 89–98.

Molnar, J.J., P.A. Duffy, L. Claxton, and C. Bailey. 2001. Private food assistance in a small metropolitan area: Urban resources and rural needs. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 28(3): 187–210.

Poppendieck, J. 1994. Dilemmas of emergency food: A guide for the perplexed. Agriculture and Human Values 11(4): 69–76.

Poppendieck, J. 1999. Sweet charity? Emergency food and the end of entitlement. New York: Penguin.

Santos, M. 2011. Bringing fresh produce to food banks. HealthyCal archive. www.healthycal.org/archives/3730. Accessed 28 May 2013.

Tarasuk, V., and J.M. Eakin. 2005. Food assistance through ‘surplus’ food: Insights from an ethnographic study of food banks work. Agriculture and Human Values 22(2): 177–186.

Vitiello, D., J.A. Grisso, R. Fischman, and K.L. Whiteside. 2013. Food relief goes local: Gardening, gleaning, and farming for food banks in the U.S. university of Pennsylvania. https://sites.google.com/site/urbanagriculturephiladelphia/food-banks-and-local-agriculture

Vitiello, D., and L. Wolf-Powers. 2014. Growing food to grow cities? The potential of agriculture for economic and community development in the urban United States. Community Development Journal 49(4): 508–523.

Weise, E. 2011. More food banks offer fresh fruits, vegetables. USA Today (January 31). http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/food/2011-01-31-foodbank31_ST_N.htm. Accessed 20 June 2012.

Wells, B., S. Gradwell, and R. Yoder. 1999. Growing food, growing community: Community supported agriculture in rural Iowa. Community Development Journal 34(1): 38–46.

Winne, M. 2007. The futility of food banks. Washington Post (November 19). http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/discussion/2007/11/16/DI2007111601442.html. Accessed 20 June 2012.

Winne, M. 2008. Closing the food gap: Resetting the table in the land of plenty. Boston: Beacon.

Winne, M., H. Joseph, and A. Fisher. 1997. Community food security: A guide to concept, design, and implementation. Venice: Community Food Security Coalition.

Zezima, K. 2008. From canned goods to fresh, food banks adapt. New York Times (December 9).

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was funded by a pilot grant from the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Public Health Initiatives (CPHI) and conducted in collaboration with the SHARE Food Program of Philadelphia. We wish to thank Steveanna Wynn at SHARE, Sheila Christopher at Hunger Free PA, Holly Beddome from the University of Manitoba, our colleagues in the CPHI, and especially the staff of food banks and partner organizations who hosted our site visits and interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vitiello, D., Grisso, J.A., Whiteside, K.L. et al. From commodity surplus to food justice: food banks and local agriculture in the United States. Agric Hum Values 32, 419–430 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9563-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9563-x