Abstract

One of the most exciting yet stressful times in a physician’s life is transitioning from supervised training into independent practice. The majority of literature devoted to this topic has focused upon a perceived gap between clinical and non-clinical skills and interventions taken to address it. Building upon recent streams of scholarship in identity formation and adaptation to new contexts, this work uses a Heideggerian perspective to frame an autoethnographical exploration of the author’s transition into independent paediatric practice. An archive of reflective journal entries and personal communications was assembled from the author’s first 3 years of practice in four different contexts and analyzed using Heidegger’s linked existentials of understanding, attunement and discourse. Insights from his journey suggest this period is a time of anxiety and vulnerability when one questions one’s competence and very identity as a medical professional. At the same time, it illustrates the inseparable link between practitioners and the network of relationships in which they are bound, how these relationships contextually vary and how recognizing and tuning to these differences may allow for a more seamless transition. While this work is the experience of one person, its insights support the ideas that change is a constant in professional practice and competence is contextual. As a result, developing educational content that inculcates contextual flexibility and an increased comfort level with uncertainty may prepare our trainees not just to navigate the unavoidable novelty of transition, but lay the groundwork for professional identities attuned to engage more broadly with change itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transition from postgraduate training into independent practice is a rite of passage in a physician’s professional life. As exciting a time as this is, it is far from seamless, often involving a move from the familiarity of one’s principal site of training to a new context of practice.

The difficulties inherent within this transition have not gone unnoticed (Borus 1982; MacDonald and Cole 2004; Higgins et al. 2005; Wilkie and Raffaelli 2005; Calman 2006; Robinson et al. 2007; Cronan 2008; Brown et al. 2009; Griffin et al. 2010; Westerman et al. 2010), with the majority of scholarship on this topic focused upon the disconnect between newly-qualified physicians’ sense of preparedness for practice in clinical abilities and their lack of comfort with abilities in “non-clinical” competencies, such as management, leadership, business acumen and understanding how to negotiate one’s role in an organization (McKinstry et al. 2005; McDonnell et al. 2007; Morrow et al. 2009; Westerman et al. 2010; Teunissen and Westerman 2011; Westerman et al. 2013). Highlighting the relative lack of formal courses and training in non-clinical skills both “before and after appointment” (Higgins et al. 2005, p. 519), interventions have largely been targeted towards final-year residents and new consultants principally to address these areas. Among these include dedicated curricular interventions in multiple specialties to facilitate transition to practice (Borus 1978; MacDonald and Cole 2004; Holak et al. 2010; Shaffer et al. 2017), an explicit re-focus of the final year of residency training as a transition to practice year (Lister et al. 2010), and calls to introduce “nonclinical tasks and roles” during clinical training (Westerman et al. 2010, p. 1916).

Yet as Calman (2006, p. 547) notes, “no matter how much preparation you do, how many books you read or courses you attend, nothing can really prepare you for that first day and the ones that follow.” One reason this may be is that transition to independent practice is more than just about learning non-clinical skills or moving into a new organizational context. As importantly, for me this period was also a transition into a new sense of self, echoing the experience of more than half of new consultants who found that their “transition from specialist registrar to consultant involved a re-examination of who and what they were” (Brown et al. 2009, p. 412).

Certain medical education scholars have conceptually considered the vulnerable moments in which a past identity must be disassembled in favour of an uncertain new one (Jarvis-Selinger et al. 2012), while others have noted that “it takes time for attendings to settle in, both at work and in their personal environment” (Westerman et al. 2010, p. 1914). Practically speaking, however, if we are to optimally support physicians during a period characterized as “the most stressful in a medical specialist’s career” (Robinson et al. 2007, p. 54), it is critical to undertake a more detailed examination of what it actually looks and feels like as attendings ‘settle in’ and re-constitute themselves as independent practitioners in new contexts. In this spirit, I set out to re-examine who and what I was during a time that can perhaps best be described as “a crisis of professional identity” (Wilkie and Raffaelli 2005, p. 107), drawing upon autoethnography and insights from the work of philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Methodology

Autoethnography has emerged as an important qualitative methodology in medical education (Farrell et al. 2015) and has been used to explore several diverse topics in the field (Darnton 2007; Gallé and Lingard 2010; Varpio et al. 2012; Farrell et al. 2017). Concerning transition to independent practice specifically, there are works with autoethnographic components scattered across several disciplines, although they take the form of practical ‘how-to’ guides or informal wisdom passed along to upcoming colleagues (Ullman 1966; Saha et al. 1999; Robinson et al. 2007; Cronan 2008; Brandt 2009; Hayden and King 2015; David and Nasir 2016). I looked to develop this implicit tradition more robustly, drawing upon Ellis’ emphasis to “connect the autobiographical and personal to the cultural and social” by privileging “concrete action, emotion, embodiment, self-consciousness, and introspection” (in Douglas and Carless 2013, p. 84). Further, I contextualized this approach by incorporating Heidegger’s (1927) understanding of being, how it is linked to anxiety and uncertainty, and how we as humans draw upon the linked “existentials” of attunement, discourse and understanding to make meaning out of the situations into which we are “thrown”. In “using (my) personal experiences as primary data; intending to expand the understanding of social phenomena; and recognizing that processes can vary and result in different writing products” (Chang 2013, p. 108), I sought to create an account that, while highly individualized, could provide significant explanatory power upon a singular time in all physicians’ lives.

This account is based upon my first 3 years of independent practice as a consultant general paediatrician, drawing from an archive of reflective journal entries and personal communications related specifically to transition as well as the challenges I encountered while working recurrently in four different Canadian practice contexts. These included two remote secondary general hospitals in rural regions in which I was the sole paediatrician, a tertiary centre general hospital in a large-urban centre with a dedicated paediatric ward and an outpatient consultation clinic in a remote location. All of these texts were re-read and analyzed descriptively at the beginning of my fourth year of independent practice. As this study and these writings are solely related to my personal experience, ethics approval was not necessary. However, I have kept all practice contexts, place names and geographies anonymous.

The end of the beginning, or, a found home

As I undertook my final year of training in a different program and city than where I completed my first three, I already had some sense that the practice of paediatrics varied between contexts. While I thought I would just pass through largely unnoticed, however, my new program and hospital welcomed me wholeheartedly. Like in my previous centre, I developed professional relationships with other residents, allied health professionals, paediatricians and families. Regardless if I was on the in-patient ward, in the emergency department (ER), or rotating through a subspecialty service, people knew me and clearly cared about me. I saw my fellow residents either daily in the hospital or in the evenings for study groups, which while useful for learning, were just as useful for talking about one’s day, negotiating the stresses of the impending licensing exam and discussing post-residency plans to come. Additionally, I felt well-supported from an administrative perspective. It was easy to arrange meetings about career advice with mentors and program directors, and the residency education office answered e-mails quickly about topics such as exam preparation.

From a Heideggerian (1927) perspective, my participation in this new system was akin to being “thrown” into it. Yet while I was “thrown” into a new hospital and training program in my final year, my expectations of uncertainty and difficulty were countered by the individual and systemic support on generous offer. Further, I had not distinctly appreciated at the time that although I had changed programs, I had maintained a stable identity as a senior resident, and the expectations others had of me remained essentially unchanged. While we always find ourselves in new situations because time is always moving forward, these are often predictable, patterned and expected from our past experience. In this sense, we are more or less “at home”—in ourselves and in our world. Even though we are always “thrown” into a complex series of relations (Elpidorou and Freeman 2015), this home-like familiarity often overshadows that complexity.

Heidegger’s (1927) example of hammering is a useful example to further illustrate how the complex associations between myself, my environment, and the tools that I used to accomplish the work of a senior resident blur together. He describes a builder using a hammer to engage in the task of hammering nails in order to make a shelter capable of providing protection from the rain. The ability to use the hammer smoothly and easily to accomplish the task of keeping one’s self warm and dry renders the tool “ready-to-hand”. It is key to note that the tools I am describing in my experience are not to be confused with tangible instruments, such as a reflex hammer or a stethoscope. Rather, the ‘hammer’ here is my biomedical lens, specifically how it enables me to ‘see’ clinically and use it to effect competent patient care. The totality with which I, like all physicians, am bound up in this worldview easily blurs the lines between our selves and our biomedical perspective. When it is “ready-to-hand”, clinical work to can be performed seamlessly and often without conscious recognition that the ability to use this tool is contextually bound.

Further, as in my prior centre of residency training, I was able to easily build up a reservoir of tacit knowledge that enabled me both to further my clinical knowledge base and to instrumentalize it to ‘get things done’ in order to provide patient care in the familiar context of this tertiary care paediatric centre. For example, I knew not only why and how to order an MRI; I had developed a sense of how to get one done urgently on an overbooked slate. I was fully bound up in my context of practice, or in Heideggerian terms, a “totality of relevance”, able to engage in skilled activity in order to seamlessly accomplish tasks without any conscious recognition of the complexities of the network of activity in which I was embedded (Heidegger 1927). In short, I had developed and maintained a strong identity as a senior paediatric resident and as a burgeoning general paediatrician, feeling deeply connected to my program and creating an unexpected professional home.

Coming undone

The sections that follow describe the uncertainties that accompanied my being “thrown” into independent practice in a variety of new contexts. Although each section focuses primarily upon each existential of attunement, discourse, and understanding in their own right, as Elpidorou and Freeman (2015, p. 663) note, “any one of the existentials mutually implies all of the others for they are inextricably linked.”

Thrown part 1: from resonance to out of tune

As the clock struck midnight on residency, I had no doubt that I was ready to set sail into the brave new world of independent practitioner. I had planned to start by doing locum work in a tertiary general hospital where I had done a clinical rotation a few months prior. I felt it would be fine; after all, I knew the paediatricians, I knew the hospital and I knew the city. Yet it felt more akin to “a real culture shock…marked by isolation and stress” (Griffin et al. 2010, p. 305). In the week between finishing training and beginning work, notes of unwelcome change began to appear. I stopped receiving a regular paycheque. E-mails to my program were answered with less speed and interest, and I received notice that my residency e-mail account was soon going to be deactivated. I had to scramble for a licensing appointment and lacked a billing number in my first few days of work, both of which took unexpected effort to organize. The electronic medical record software in the office was strikingly different, and although I had learned to dictate during residency, reports inevitably piled up by the end of the office day, adding hours of work. The medical office assistants finally gave in and made me my own key so they could go home at a reasonable time. Instead of having a few minutes to review with an attending paediatrician, allowing me to gather my thoughts, I had to transition immediately into discussing my impression with a nervous and expectant parent. As a result, things felt all over the place, caregivers often appeared confused, and more than one family left without bloodwork requisitions I had forgotten to print off and give to them.

I had only scratched the surface of the unexpected complexities awaiting me in the first months of independent practice (Morrow et al. 2009), and the hospital itself was not much better. I was constantly introducing myself to not just parents and children I was looking after but unit clerks, nurses, other physicians and learners who had no idea who I was. Physicians calling for paediatric advice would have an audible note of disappointment in their voice when they realized it was me on the other end of the line and not the person for whom I was locuming. In residency, the responsibilities given to me allowed me to move easily between the multiple areas I was covering on-call. Yet now, my pager beeped incessantly, interrupting work in one place, such as reviewing an ER consult, for immediate attention in another, such as attending a delivery. Unlike as a senior resident, where I was confident entrusting certain tasks to junior residents and medical students, I now felt uncertain at best and borderline paralyzed far more than I cared to admit openly. As I wrote in an e-mail to my former program director a few months into independent practice:

These last few months have been far more stressful than I had ever expected. From significant amounts of unexpected expenses on licensing fees, to the rapid change of financial management that comes when one no longer receives a regular paycheque, to the beginning of loans to pay back, to the feelings of precarity that accompany the excitement of no longer having to review with anyone, it’s been hard.

Thrown part 2: What do you mean? Or, discourse derailed

“You can write ‘breast as a gift’,” my nursing colleague told me as I was writing orders. We were in the nursery of the secondary general hospital where I was starting a seven-day call stint for the first time. “Okay. Breast as a…wait, what?” was my confused response. Apparently, this meant not including breastfeeding in the baby’s planned daily total fluid intake. An innocent use of language on the one hand, but also a harbinger of what would follow. Having spent the vast majority of my training in tertiary paediatric centres, my default setting was working with other paediatricians, nurses, respiratory therapists and child life workers, all of who practiced exclusively in paediatric settings. Despite different backgrounds, there was a significant repository of shared assumptions, relevance, language use and dedicated paediatric expertise upon which to draw, that, in retrospect, allowed conversation to flow easily, orders to be followed through without difficulty and worrisome changes in clinical status to be readily communicated.

Here, however, for me “the new hospital (was) unfamiliar, and its organizational structure, culture, patient population, policies, and atmosphere (were) completely unknown” (Westerman et al. 2010, p. 1916). Children were admitted to an in-patient ward of all ages. While the nurses clearly meant well, their expertise was general, reflected in simultaneous patient assignments of a 6-month-old with bronchiolitis, a 55-year-old recovering from a heart attack and a 72-year-old struggling with an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. They would page for seemingly trivial concerns, yet they might not call if someone significantly worsened overnight with an asthma exacerbation. In procedural or critical care scenarios, things I had come to take for granted—nursing colleagues knowing how to hold an infant during a lumbar puncture or respiratory therapists having a suction set up at the bedside prior to intubation, for example—were absent. What had been tacitly understood in residency needed explicit discussion and re-iteration in these new spaces; the lack of shared relevance led me to feeling frustrated with new colleagues and shaky in my ability to trust them.

Compounding this was the significant difficulty of providing phone advice and organizing air medical evacuation for assessment from remote nursing stations. Place names were completely unfamiliar; further, I had no idea of the skill level or comfort of the nurses calling, whether I could trust their clinical findings, and which services they could even provide in the community. That the calls continued around the clock, interrupting morning rounds, afternoon clinic and attempts at sleep, only added to the level of stress. I struggled with not being able to physically see a child or ask a caregiver questions directly. Instead, while I desired to be a careful steward of health care resources, I found myself medevac’ing far more children than was necessary because I could not get a clear handle if the child in question was well enough to stay in their community. As I noted to a colleague in an e-mail:

After I finished residency, I had a (very) foolish idea that I was ready to be a really good practitioner of paediatrics. I think residency prepared me to be a safe practitioner, but to be a really good consultant in the community? Much less convinced right now.

Thrown part 3: How do I do this again?

Perhaps the biggest challenge to confront me with loss of meaning, however, was the growing uncertainty in my clinical abilities. I had thrived in an academic tertiary paediatric centre, priding myself on making judicious use of consultants but also erring on the side of caution when I felt uncertain. Here, it was easy to have a cardiology fellow come ‘take a quick listen’, for example, when I was unsure about a murmur. In addition, while I had had some exposure to children struggling with behavioural, developmental and mental health concerns, these were the vast minority of interactions during my residency, limited to a developmental paediatrics rotation or a crisis situation in the ER that meant child or adolescent psychiatry support was readily available. Finally, the bloc-based nature of my program made my experience with outpatient care a one-off enterprise. It was standard as a resident to see someone once, pronounce a diagnosis, order a slew of tests and—thanks to the vagaries of my moving on to the next rotation—never see them again to know directly whether those were indeed helpful interventions.

Once in independent practice, I was confronted with biomedical conditions I had studied for but never seen, such as a toddler with myocarditis, a newborn missing part of their chest wall due to an undiagnosed congenital condition, or the time a girl showed up in the ER in florid respiratory failure secondary to a catastrophic pulmonary hemorrhage. Other conditions I had extensive comfort with, such as eczema, were far worse than I had seen in training; it often looked akin to a burn injury, driven by MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) superinfection, an inability for many families in outlying communities to access regular paediatric care and poor living conditions aided and abetted by structural violence. I saw numerous children for obesity and laid out what I had thought was a comprehensive care plan, only to see many return 3 months later having gained another five kilograms. I confidently diagnosed a child with what I thought was a viral rash, saw him the next day when he seemed much better both to his mother and myself, and watched him come back to the ER the following night with intussusception secondary to what was actually an atypical presentation of Henoch–Schönlein purpura.

Further, the consultations for behavioural, developmental, and mental health concerns were a recurrent feature across all four practice contexts in which I worked. I had only a sliver of experience with autism, anxiety, language delay, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities and self-harm, yet I was the consultant to whom these questions were directed. As I wrote to a friend and colleague:

I can do a developmental screen, but making judicious referrals for complex behavioural consults are a real challenge. The amount of potential psychiatric issues are staggering, while the resources in the community for appropriate referral are sadly limited.

Many of the families that I saw for these concerns had been waiting months with their children clearly struggling, and trying to develop an efficient yet comprehensive approach—not to mention a fluent grasp of locally available diagnostic and rehabilitation services—was akin to a crash course in a second residency albeit without supervision and guidance. Finally, I agonized over when to schedule follow-up and to gauge which children I actually needed to see again, who could be safely followed by their family physician, and how I could be available for ongoing support yet not put unnecessary burden on the health care system or extend waitlists to years on end. In a discussion with a mentor, she empathized with this difficulty:

I think residency prepares us to take care of children with DORV (double-outlet right ventricle – a congenital cardiac lesion), which we almost never see, and far less for ADHD, which we see all the time.

I remember how proudly I had written FRCPC (Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada) after my name for the first time just a few months prior, a tangible reminder that I was now a fully-qualified paediatrician. But increasingly, I felt I should instead be writing FRAUD. The relationships that previously made skilled activity possible literally without a second thought in my resident identity veered towards “unready-to-hand” as a novice independent practitioner. Suffice to say, I was not just “thrown” into the novel situation of independent practice, but thrown out of my previous comfort zone and thrown off the patterns I had come to expect. As a result, the seamless integration of activity I had felt as a senior resident fell apart, my ability to make meaning largely evaporated for the time being, and I felt ripped open and broken as an attending.

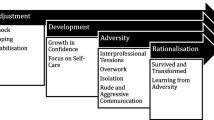

Re-constitution, or, the way back to the future

From unready-to-hand to present-at-hand

In step with the growing recognition of the key role that emotion plays in learning and practice in health professions education (Dornan et al. 2015; Leblanc et al. 2015), the described difficulties of my transition to independent practice are laced with leitmotifs of anxiety and uncertainty. As Heidegger (1927) notes, we are not just “thrown” into situations; rather, we always find ourselves there in a type of mood. As a fundamental mood, anxiety renders what had been a familiar world, foreign, and what had been easily understandable, unintelligible (Wheeler 2016). As a result, “one feels at home nowhere” (Elpidorou and Freeman 2015, p. 667). In sharp contrast to the fluid, everyday activity we come take for granted, anxiety turns us away from this, rendering us out of tune with the situation and out of sync with the world we had thought we had known.

Paradoxically, though, it is also in anxiety that we may see ourselves for who we really are (Elpidorou and Freeman 2015). When things do break down, the blurring between actor and tool that had allowed fluid activity to happen seamlessly separates out into elements that we can consciously distinguish—often for the first time—and understand how they actually articulate (Heidegger 1927). Otherwise put, the situation becomes “present-at-hand”. Finding ourselves consciously in anxiety and homeless in the world that formerly felt familiar impels us forward towards possibilities to make ourselves at home again (Wheeler 2016). We are driven to make meaning to attune ourselves to new situations and to move towards “readiness-to-hand” (Heidegger 1927).

Yet to do so, we need a way by which we become consciously aware of the circumstances that have thrown spanners in the gears of our typical ability to make meaning. As Ellis (in Holman Jones et al. 2013, p. 34) comments, “I tend to write about experiences that knock me for a loop and challenge the construction of meaning I have put together for myself. I write when my world falls apart or the meaning I have constructed for myself is in danger of doing so”. Like Ellis, one of the anchors that kept me moored at a time where so much felt adrift was continuing my writing practice that I had begun 15 years before as a university undergrad. Unlike in the past, however, I began re-reading what I had written as a self-dialogue to provide a way forward during this difficult time. Pieces such as the following from my journal approximately 18 months into practice point to this growing consciousness:

My definition of paediatrician has been broadened, my understanding of the standardization of competencies contextualized, my definition of what Canada is, expanded beyond measure. Who am I now? Who am I becoming? How does context call me into being? I am undone and remade everyday, as we must be. Nothing happens in a vacuum. How could it?

Writing enabled me to recognize for the first time that my clinical knowledge and practice ability would stay “unready-to-hand” as long as I remained tethered to a resident identity and relied principally on the tacit understandings that had enabled me to work as that specific person, in that specific context, in that specific time. Otherwise put, as a finishing senior resident my clinical knowledge had been “ready-to-hand”, not just because I had incorporated a biomedical paediatric lens, but because I was able to instrumentalize it through a role that I had come to inhabit as second nature and through deep and tacit understandings of practices and organizations that enabled its effective use in my residency centres of training. When I was “thrown” into new contexts of practice in a new role, that clinical knowledge became to some degree “unready-to-hand”. It was not that I was broken or as though I had forgotten how to do a neonatal resuscitation, treat asthma, or recognize when someone had gotten sicker. Rather, it was that I could no longer instrumentalize it in habitual ways to do as an attending what I had become used to doing as a resident.

Attunement discourse understanding, re-united – or, building a new home

Writing further served as a way of making the “totality of relevance” in each of my new contexts “present-at-hand”, allowing me to consciously examine the unfamiliarities of my new world and harness them in productive ways to re-constitute myself as an attending. Practically speaking, this meant engaging in concrete approaches I transferred from residency, including redoubled efforts to read around clinical presentations and investing significant energy in order to expand my clinical repertoire to include a well-developed approach to behavioural, developmental and mental health concerns—in diagnosis, differential diagnosis and general management strategies.

In addition, as Kilminster et al. (2011, p. 1013) suggest, “performance does not depend only on individual attributes, but is fundamentally affected by organizational practices, activity and cultures”. In order to instrumentalize my knowledge in these new contexts, I had to learn those practices, activities and cultures in which I now found myself and also incorporate myself into those networks of relations. This meant developing an attuned sense of available resources in each context of practice and learning to harmonize a general approach to local systemic variations in each place I worked. For example, some places had an embarrassment of riches when it came to getting psychoeducational testing organized and infant development services provided. Others had much less in terms of resources, but recognizing I could meet people ‘where they were’—such as going on school visits or making time to sit down with allied health professionals as a group—allowed me to make judicious and creative use of what was available,

It also required finely tuning clinical skills and critical care comfort in remote locations in ways different than in the dedicated paediatric centres in which I had grown up professionally. In this way, anxiety served as a motivator for improvement. I learned over time that the best way for me to confront it was to prove to myself clinically and comprehensively that I was unlikely to miss something important. As I wrote to a colleague:

Somehow you have to get comfortable when the cardiologist and the echocardiography machine are 3½ hours away, and your confidence in your work-up for a murmur heard on day two of life—for a baby who otherwise looks and examines well and who will go home to a remote community even further away—may not be 100%.

As for direct management of critical situations, I drew on a metaphor of being a conductor in a symphony. In addition, though, I recognized that my colleagues, while trying their best, were at a different level of paediatric comfort and might have differing frames of relevance. As I remarked in an e-mail to a colleague:

As a paediatrician in a general centre, your knowledge and disposition is far different often than those you will work with. For example, the nurses are excellent yet there is a dance between respecting their skill set while also recognizing your knowledge on the situation (as well as experience) is likely far greater.

For example, I needed to frequently provide in-time feedback around things such as bag and mask ventilation, emphasize closed-loop communication and be much more deliberate in making sure preparation for invasive procedures was adequate. I learned to ask certain questions when outlying centres called—including the caller’s level of comfort—that made transfers into the hospital much more efficient. To extend the metaphor, conducting sometimes was not enough; it was at times necessary to show one’s first violinist—a nursing, general practice physician or respiratory therapist colleague, for example—how to play their instrument in the context of care for a critically ill infant.

Finally, I learned that my expertise and comfort was both enabled and limited by my context of practice, and I had to be okay with that. For example, I had no problems putting umbilical lines into neonates and keeping them under my care or monitoring a baby with a known respiratory infection who needed frequent secretion management and high-flow oxygen, but nursing expertise and availability in that context meant that they had to be transferred out to specialized centres. Initial frustrations around obesity management—as raised above—opened up entire avenues of thought around advocacy and structural issues of healthy food access and safety for exercise in remote communities, and reminded me paediatrics is a practice that extends far beyond the walls of the clinic. As I wrote in my journal:

The growth curves of independent paediatric development are steep, and in the daily struggles to induce some sort of general rules of practice from daily interactions, one could be forgiven for having originally mistaken the vast, comprehensive child health forest that I have entered as an attending for the relatively small section of acute care centre trees in which I grew up as a resident.

Combined with the growing familiarity of the places in which I was recurrently working and moving further in time into independent practice, I began to slowly but surely feel at home again—both in my new identity as an independent practitioner as well as in my contexts of practice where I had to tune that new stance towards the variability that existed in each. In so doing, competence—both my internal sense of it and how I believed others viewed it—felt restored, re-anchoring my identity as a medical professional, this time as one capable of providing safe and effective clinical care independent of supervision. Yet this remains a work in progress; stabilizing a new identity as an independent practitioner is a years-long process, one in which I still find myself re-constituting a new home from the integration of past pieces, current experiences and the influences of future plans.

Limitations

The utility and drawback of autoethnography is its ‘N of 1’ orientation. It is powerfully able to explore a phenomenon in depth and granular detail and use those highly personal insights to illuminate broader issues common to many. Yet the way in which it produces knowledge remains highly personalized, which opens up necessary consideration as to the degree to which its insights are indeed generalizable to others. While I read my journal entries and actively engaged in discussion with other colleagues recurrently during this time period, the manner in which this story was assembled is from a look back with the perspective of one now a few years into practice. It is reasonable to suggest that the level of emotionality and details included within this text, therefore, may be different than had I written it in the first year of practice when it felt far from certain that everything was going to be all right. As McConnell and Eva (2012, p. 1320) note, “emotional experiences, particularly negative ones, are more likely to be mulled over than non-emotional experiences.” As a result, reflective journal writing spurred by challenges to “the construction of meaning I have put together for myself” (Ellis, in Holman Jones et al. 2013, p. 34) is likely going to include preferentially events that were more trying than mundane details that quickly faded into the background or the numerous situations where things, no doubt, went well.

In addition, Heidegger’s intent and messaging in both Being and Time and his greater corpus of work remain under active exploration even 60 years after his death. I have endeavoured to remain faithful to my reading of the original text as well as judiciously incorporate several commentaries to inform this current work. However, I must note that this account is largely descriptive in orientation rather than critical. Further work that, for example, discursively explores deeper social, cultural and historical conditions that might make transition troublesome, or how this developmental period might be experienced and embodied differentially by those whose identities intersect differently than mine are needed perspectives to incorporate into this discussion. Finally, while competency-based frameworks such as the Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) are increasingly shared by medical education systems in multiple nations, this work is an illustration that microcultures and contexts of clinical practice vary importantly even within a single discipline, a single province and a single country. Nonetheless, I remain optimistic that the insights available here offer complementary thinking points for consideration of how transition to independent practice might be better approached, irrespective of one’s situation.

Conclusion

In their work on earlier transitions in training, Kilminster et al. (2011, p. 1013) suggest that physicians “can never be fully prepared in advance of a transition because learning, practice and performance are inseparable and each depends on the others.” Indeed, on the one hand, despite all the preparation in the world, we cannot know the future that awaits us or our learners. What we can say, however, is that the transition into independent practice that all physicians face has the potential to be an unexpectedly vulnerable time, one that challenges one’s sense of competence, and, by extension, one’s professional identity. This issue will only continue to gain importance as locum employment and working in multiple contexts is a reality that more and more new practitioners in the UK and Canada are facing in their first few years of independent practice (Griffin et al. 2010; Fréchette et al. 2013).

What we can also say is that change is a constant, a recurrent theme of health care practice and one’s professional trajectory. While nothing will mitigate the anxiety that accompanies the arrival of the future, explicit cultural and institutional recognition of the depth of change in transition may make that anxiety predictable, rendering it far less crippling and much more productive. There is currently a lack of suitable preparation for the emotional and interpersonal challenges that arise with the onset of independent practice, and expanding promising initiatives such as peer mentorship groups for final-year residents and newly-minted attending physicians (Wilkie and Raffaelli 2005; MacMillan et al. 2016) is paramount. Further, national bodies such as the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada have now explicitly included ‘Transition to Practice’ as part of the continuum of competence spanning a professional career (Royal College 2015). While this is a welcome development, it focuses exclusively on the period prior to certification and independent practice. Echoing others’ calls for establishing a months-long period for post-certification support (Griffin et al. 2010), I suggest that national licensing bodies and training programs give serious consideration to conceptualizing transition as a period that encompasses both sides of the certification divide.

Finally, the last thing we can say is that while transition to independent practice is considered largely from a perspective of individualism, we are never “thrown” into a vacuum. Indeed, using one’s biomedical abilities and enacting a professional identity of physician are never a-contextual; rather, as illustrated, they are critically dependent upon on a networked set of relationships that allow this ability to be “ready-to-hand”, which in turn allows contextually competent activities of skilled health care to flourish. This understanding, combined with an emphasis upon identifying which component pieces in each context allow a clinical disposition to be enacted, may help us as a field to render the inevitability of major transitions much more seamless for those following us. In the final balance, then, developing educational content that inculcates contextual flexibility and an increased comfort level with uncertainty may prepare our trainees not just to navigate the unavoidable novelty of transition, but lay the groundwork for professional identities attuned to engage more broadly with change itself.

References

Borus, J. F. (1978). The transition to practice seminar. American Journal of Psychiatry, 135(12), 1513–1516.

Borus, J. F. (1982). The transition to practice. Journal of Medical Education, 57, 593–601.

Brandt, M. T. (2009). Transitioning from residency to private practice. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 20, 1–9.

Brown, J. M., Ryland, I., Shaw, N. J., & Graham, D. R. (2009). Working as a newly appointed consultant: A study into the transition from specialist registrar. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 70(7), 410–414.

Calman, F. (2006). Preparing for the first day of the rest of your life. How should we train clinical oncology consultants? Clinical Oncology, 18, 547–548.

Chang, H. (2013). Chapter 3: Individual and collaborative autoethnography as method. In S. Holman Jones, T. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 107–122). Oxford: Routledge.

Cronan, J. J. (2008). My first job: The transition from residency to employment: What the employer and employee should know. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 5, 193–196.

Darnton, R. (2007). Crossing the PBL divide: From PBL medical student to medical teacher. Medical Education, 41, 222–225.

David, E. A., & Nasir, B. S. (2016). Transition to practice, lessons learned: Academic general thoracic surgery. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 151, 920–924.

Dornan, T., Pearson, E., Carson, P., Helmich, E., & Bundy, C. (2015). Emotions and identity in the figured world of becoming a doctor. Medical Education, 49, 174–185.

Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2013). Chapter 2: A history of autoethnographic enquiry. In S. Holman Jones, T. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 84–106). Oxford: Routledge.

Elpidorou, A., & Freeman, L. (2015). Affectivity in Heidegger I: Moods and emotions in being and time. Philosophy Compass, 10(10), 661–671.

Farrell, L., Bourgeois-Law, G., Ajjawi, R., & Regehr, G. (2017). An autoethnographic exploration of the use of goal oriented feedback to enhance brief clinical teaching encounters. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 22(1), 91–104.

Farrell, L., Bourgeois-Law, G., Regehr, G., & Ajjawi, R. (2015). Autoethnography: Introducing ‘I’ into medical education research. Medical Education, 49, 974–982.

Fréchette, D., Hollenberg, D., Shrichand, A., Jacob, C., & Datta, I. (2013). What’s really behind Canada’s unemployed specialists? Too many, too few doctors? Findings from the Royal College’s employment study. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Gallé, J., & Lingard, L. (2010). A medical student’s perspective of participation in an interprofessional education placement: An autoethnography. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24, 722–733.

Griffin, A., Abouharb, T., Etherington, C., & Bandura, I. (2010). Transition to independent practice: A national enquiry into the educational support for newly qualified GPs. Education for Primary Care, 21(5), 299–307.

Hayden, S. R., & King, E. M. (2015). Preparing for the transition to practice: A compilation of advice from program directors to residency graduates. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 49(6), 937–941.

Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and time (Sein und Zeit, J. Stambaugh, Trans.). (1996). Albany: SUNY Press.

Higgins, R., Gallen, D., & Whiteman, S. (2005). Meeting the non-clinical education and training needs of new consultants. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 81, 519–523.

Holak, E. J., Kaslow, O., & Pagel, P. S. (2010). Facilitating the transition to practice: A weekend retreat curriculum for business-of-medicine education of United States anesthesiology residents. Journal of Anesthesiology, 24, 807–810.

Holman Jones, S., Adams, T., & Ellis, C. (2013). Introduction: Coming to know autoethnography as more than a method. In S. Holman Jones, T. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 17–48). Oxford: Routledge.

Jarvis-Selinger, S., Pratt, D. D., & Regehr, G. (2012). Competency is not enough: Integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Academic Medicine, 87(9), 1185–1190.

Kilminster, S., Zukas, M., Quinton, N., & Roberts, T. (2011). Preparedness is not enough: Understanding transitions as critically intensive learning periods. Medical Education, 45, 1006–1015.

LeBlanc, V. R., McConnell, M. M., & Monteiro, S. D. (2015). Predictable chaos: A review of the effects of emotions on attention, memory and decision making. Advances in Heath Sciences Education, 20, 265–282.

Lister, J. R., Friedman, W. A., Murad, G. J., Dow, J., & Lombard, G. J. (2010). Evaluation of a transition to practice program for neurosurgery residents: Creating a safe transition from resident to independent practitioner. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 2, 366–372.

MacDonald, J., & Cole, J. (2004). Trainee to trained: Helping senior psychiatric trainees make the transition to consultant. Medical Education, 38, 340–348.

MacMillan, T. E., Rawal, S., Cram, P., & Liu, J. (2016). A journal club for peer mentorship: Helping to navigate the transition to independent practice. Perspectives in Medical Education, 5, 312–315.

McConnell, M. M., & Eva, K. W. (2012). The role of emotion in the learning and transfer of clinical skills and knowledge. Academic Medicine, 87, 1316–1322.

McDonnell, P. J., Kirwan, T. J., Brinton, G. S., Golnik, K. C., Melendez, R. F., Parke, D. W., et al. (2007). Perceptions of recent ophthalmology graduates regarding preparation for practice. Ophthalmology, 114, 387–391.

McKinstry, B., Macnicol, M., Elliot, K., & Macpherson, S. (2005). The transition from learner to provider/teacher: The learning needs of new orthopaedic consultants. BMC Medical Education, 5, 17.

Morrow, G., Illing, J., Redfern, N., Burford, B., Kergon, C., & Briel, R. (2009). Are specialist registrars fully prepared for the role of consultant? The Clinical Teacher, 6, 87–90.

Robinson, G., Morreau, J., Leighton, M., & Beasley, R. (2007). New hospital consultant: Surviving a difficult period. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 120(1259), 54–57.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. (2015). The competence by design competence continuum. Retrieved January 20, 2018 from http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/framework/competence_continuum_diagram_e.pdf.

Saha, S., Saint, S., Christakis, D. A., Simon, S. R., & Fihn, S. D. (1999). A survivalist guide for generalist physicians in academic fellowships part 2: Preparing for the transition to junior faculty. The Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14, 750–755.

Shaffer, R., Piro, N., Katznelson, L., & Hayden Gephart, M. (2017). Practice transition in graduate medical education. The Clinical Teacher, 13, 1–5.

Teunissen, P. W., & Westerman, M. (2011). Opportunity or threat: The ambiguity of the consequences of transitions in medical education. Medical Education, 45, 51–59.

Ullman, M. (1966). On the transition from private practice to general hospital psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry, 14, 261–269.

Varpio, L., Bell, R., Hollingworth, G., Jalali, A., Haidet, P., Levine, R., et al. (2012). Is transferring an educational innovation actually a process of transformation? Advances in Heath Sciences Education, 17, 357–367.

Westerman, M., Teunissen, P. W., Fokkema, J. P. I., van der Vleuten, C. P. M., Scherpbier, A. J. J. A., Siegert, C. E. H., et al. (2013). The transition to hospital consultant and the influence of preparedness, social support and perception: A structural equation modelling approach. Medical Teacher, 35(4), 320–327.

Westerman, M., Teunissen, P. W., van der Vleuten, C. P. M., Scherpbier, A. J. J. A., Siegert, C. E. H., van der Lee, N., et al. (2010). Understanding the transition from resident to attending physician: A transdisciplinary, qualitative study. Academic Medicine, 85(12), 1914–1919.

Wheeler, M. (2016). Martin Heidegger. In E. N. Zalta (Eds.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved June 13, 2017, from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/heidegger/.

Wilkie, G., & Raffaelli, D. (2005). In at the deep end: Making the transition from SpR to consultant. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 11, 107–114.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Dr Joanna Bates and Dr Anne Rowan-Legg for both the time they took to read earlier versions of this manuscript as well as the helpful comments provided for its revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schrewe, B. Thrown into the world of independent practice: from unexpected uncertainty to new identities. Adv in Health Sci Educ 23, 1051–1064 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-9815-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-9815-4