Abstract

Reciprocity is a powerful motivation in social life. We study what older people give to their family for help received. Data are from the Panel on Health and Aging of Singaporean Elderly, Wave 2 (2011; persons aged 62+; N = 3103). Giving and receiving help are with family members other than spouse in the same household, in the past year. Types of help given and received are money, food/clothes/other material goods, housework/cooking, babysitting grandchildren, emotional support/advice, help for personal care, and help for going out. Multivariate models predict each type of giving help, with independent variables about the older person’s resources, needs, and help received. Reciprocity is demonstrated by positive relationships between receiving and giving help. Results show two kinds of reciprocity: “nontangibles for tangibles” and “same for same.” First, older people give their time and effort in return for money and material goods. This aligns with contemporary Singapore circumstances, in that older people tend to have ample time but limited financial resources, while family members (often midlife children) have the reverse. Second, same-for-same exchanges, such as housework both given and received, are shared tasks in families or normative behaviors in Singapore society. The results replicate and extend prior ones for Singapore. We discuss prospects for change in frequency and shape of family reciprocity as the state continues to modernize.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reciprocity is a strong and abiding principle in social relationships. When someone gives a material gift or service to another person, the recipient often feels that more than “thank you” should be offered in return. That may not happen soon, or in the same exact manner, but the motivation to reciprocate persists. As people return favors and goods for those received, reciprocity makes for powerful bonds of amity and trust in social communities. Reciprocity occurs in all arenas of social life, ranging across family, work, play, love relationships, organization management, and more. This analysis studies within-family social exchanges, asking how older persons who receive tangibles (money or material goods) and nontangibles (services of time and effort) reciprocate with their family. We study exchanges in Singapore, a swiftly modernizing society in which family ties are strongly valued and retained.

Background

The theoretical springboard for this analysis is social exchange theory (Simmel 1907, 1922). A central premise is reciprocity, namely, that people want and try to “give in return” for gifts and services received. Social exchange theory and reciprocity have been elaborated since Simmel’s insights, with increasing empirical orientation (Blau 1964; Gouldner 1960; Homans 1961; Kolm 2008; Kranton 1996; Molm 2003; Molm et al. 2007a; Purdam and Tranmer 2014; Thomése et al. 2005).Footnote 1 Types of giving and receiving behaviors include material goods, time, effort, space, overt affection, stated appreciation, and more. Motivations underlying reciprocity include obligation, altruism, emotional attachment, self-interest, social productivity, future benefits, and more (Beel-Bates et al. 2007; Fingerman et al. 2009; Horioka et al. 2016; Kolm 2008; Molm 1997; Silverstein et al. 2012).Footnote 2 Research on reciprocity assesses observed links between receiving and giving behaviors, and motivations are inferred from the links.Footnote 3

Purpose of analysis

We study giving and receiving help by older Singaporeans with their family members in the past year. The giving/receiving behaviors include tangibles (money, food/clothes/other material goods) and nontangibles (services requiring time and effort such as babysitting, housework, cooking, personal care, accompanying someone out of the house for appointments/errands, offering emotional support, providing advice). Empirical links between receiving and giving demonstrate the strength and types of reciprocity within families.

In Singapore society, there is longstanding dependence of older persons on their children for support and care. But Singapore is a well-known example of rapid state modernization, changing from “third world” to “first world” infrastructure and economy in just five decades. Amid swift modernization, what kinds of giving and receiving help are common in families and are reciprocal exchanges of help common? The contribution herein is understanding the strength and types of family reciprocity in Singapore, using good-quality data and analysis techniques. We test three hypotheses:

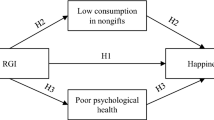

Hypothesis 1 Strong reciprocity exists between receiving and giving help with family members. Empirically, we expect statistically significant positive relationships between receiving and giving help. Hypothesis 2 For older persons, giving nontangibles for received tangibles is a typical form of reciprocal exchange. In return for money and material goods, older people give services that entail time and effort (physical, mental, emotional). Hypothesis 3 Receiving help is the strongest predictor of giving help, compared to other predictors about older persons’ psychosocial resources and health. Reciprocity is so powerful a motivation in social ties that it supercedes effects of personal features that prompt or inhibit older people to give help to family.

Methods

Data source

The data source is Wave 2 (2011) of the Panel on Health and Aging of Singaporean Elderly (PHASE). PHASE is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of older Singaporeans aged 60+. For Wave 1 (2009), a national sample of households was contacted for presence of persons aged 60+ (Malhotra et al. 2010); 4990 persons were interviewed (response rate 69.4%). In Wave 2 (2011), 3103 of them were reinterviewed (aged 62+; response rate 67.5% for alive located persons). Weights were generated to adjust for nonresponse (see Procedures). The questions about giving and receiving help were introduced in Wave 2; they are not in Wave 1.

Scope of analysis

The Wave 2 social exchange data cover central helping actions in older persons’ lives, but not all. What aspects of social exchange do the data cover, and not cover? First, the social exchanges are among family members, namely relatives in same household. Other valued exchanges are not queried, such as with kin living elsewhere, friends, or coworkers. Second, the older adult is the focal person. Helping behaviors are based on his/her reports, not those of other household members. Third, the data concern behaviors, not motivations, perceptions, or expectations. We infer positive motivation to reciprocate from empirical results showing two-way exchanges. Fourth, social exchanges in the past year are treated as contemporaneous, occurring in a recent timeframe. The data do not show timing of giving and receiving actions within that period.

Dependent variables

The dependent variables are types of help given by an older person to his/her family. Respondents were asked whether they gave these to any family members in the past 12 months: babysit grandchildren; money; housework or cooking help; food or clothes; and emotional support or advice. “Family members” are relatives in the same household except spouse. (Maids are common for cooking, cleaning, and child/elder care in Singapore households of many income levels. They are not relatives, so not “family members.”) “Babysit grandchildren” is analyzed just for older persons who have any in the household. “Money” can be regular, occasional, or holiday gifts. The five items are dichotomous (yes 1, no 0). We classify types of help as tangibles (money, material goods) and nontangibles (babysit, housework/cooking help, emotional support/advice).

Independent variables

The predictors reflect older persons’ resources, needs, and abilities to give help. We include sociodemographic features, time commitments, availability of potential receivers of help and of other potential givers of help, psychosocial features, illness and disability, and receipt of help.

The sociodemographic variables are gender, age (62–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75+), ethnic group (Chinese, Malay, Indian/Other), marital status (married, widowed, other nonmarried), education (no formal education, primary, secondary, above secondary), housing type (public housing 1–2 rooms, 3 rooms, 4 rooms, 5+ rooms/private housing), perceived income adequacy (much difficulty to meet expenses; some difficulty to meet expenses; just enough money, no difficulty; enough money, with some left over). Income adequacy does not signify income level; “just enough” and “enough with some left over” can be true for rich or poor people.

For time commitments, we use employment status (not working, working part-time, working full-time).

Availability of potential receivers, and presence of other potential givers, can affect how readily an older person (R, respondent) gives help. We created five variables about household members: numbers of R’s children in the household, R’s grandchildren in the household, other household members aged 19–59, other household members aged 60+, and maids. “Other household members” include R’s spouse and exclude R’s children, grandchildren, and maids. The availability variables are mutually exclusive.

Psychosocial features affect motivations to give help to others. Perceived loneliness is measured by the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al. 2004) (3 items; range 3–9; Cronbach’s α for Wave 2 data = .86). Depression symptoms are measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Kohout et al. 1993) (11 items; range 0–22; α = .75). Personal mastery is measured by the Pearlin Mastery Scale (Pearlin and Schooler 1978) (5 items; range 5–20; α = .88). Social network support (frequency and intimacy of social contacts outside the household) is measured by the Lubben Social Network Scale (Lubben 1988; Lubben and Gironda 2004) (12 items; range 0–60; α = .87). Lubben items about “relatives” were modified in PHASE surveys to “relatives not living with you,” in order to separate social network support from family activities. The psychosocial features are asked in self-response interviews, not proxy interviews (see “Procedures” section).

Illness and disability are measured by self-rated health (very healthy, healthier than average, of average health, somewhat unhealthy, very unhealthy), vision and hearing (no difficulty, difficulty with one of them, difficulty with both), chronic conditions (count of 18 physician-diagnosed conditions), physical limitations (count of nine upper and lower extremity actions difficult to perform alone), ADL disabilities (activities of daily living, or personal care; count of health-related difficulties in seven ADLs without personal or device assistance), and IADL disabilities (instrumental activities of daily living, or household management; count of health-related difficulties in seven IADLs without personal or device assistance).

Receiving help is the key predictor for the analysis. Respondents were asked whether they received these from any family members in the past 12 months: money; housework help; food, clothes, or other material goods; physical care such as help with eating, bathing, toileting, moving around the house; help to go to the doctors, marketing, shopping, go out to visit friends, using public transportation; and emotional support or advice. “Family members” are relatives in the same household except spouse. “Money” can be regular, occasional, or holiday gifts. Physical care is called ADL help herein, and help to go out is called IADL help. The six items are dichotomous (yes 1, no 0). We classify them as tangibles (money, material goods) and nontangibles (housework help, ADL help, IADL help, emotional support/advice).

The set of independent variables is large so results of receiving help (X) on giving help (Y) are well-controlled. They are sometimes called predictors, but no causality is intended.

Procedures

Sampling weights for Wave 2 were calculated to adjust for nonproportional sampling (Wave 1; age and ethnicity) and selective nonresponse (Waves 1 and 2; regression-based; age, gender, and ethnicity). Dependent variables had no missing data. Predictors had little missing data (exception shortly), and we coded such cases to the mode. Psychosocial measures had substantial missing data due to proxy interviews (N = 291; 9.4%). Multiple imputation by chained equations (Raghunathan et al. 2001) was used to create ten imputed datasets for statistical analyses where psychosocial items are included. Combination rules specified by Rubin (1987) adjusted for the variability of coefficients and standard errors between datasets.

Relationships between predictors and dependent variables were estimated using the Stata MICE procedure (StataCorp 2013). We started with bivariate relationships using logistic regression and then moved to multivariate logistic regressions. Models are for each type of giving help (Y) separately. Predictor effects are shown by odds ratios (OR). Significance levels are ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05. Only statistically significant findings are stated in Results, with their OR and significance level. Results and conclusions are based on collections of effects across models (such as % of a predictor’s effects that are statistically significant across models), not single (one model) effects.

Pseudo R2 values for models were generated by Stata for full-sample models (N = 3103). A straightforward method to produce them for models with imputed data is not currently available, so when psychosocial features are included, we use complete-case models (N = 2812) instead. Fortunately, explorations proved that predictor effects for models using N = 2812 and N = 3103 are almost identical, so this is acceptable.

Results

Sample descriptives

In the Wave 2 PHASE survey, half of the respondents are aged 75+ (45.2%; mean age 74.1) and a majority are female (54.5%) (Table 1). Respondents are largely Chinese (71.5%), married (57.0%), and have no formal or primary education (70.8%). The majority live in a 4-room or larger public flat (64.4%), and almost all report adequate income to meet needs (90.4%). Most respondents are not employed (81.1%). Many respondents live with one or more of their own children (66.1%; includes children’s spouses), and one-quarter live with any grandchildren (28.6%). A majority live in households with other people aged 60+ (53.4%; likely their own spouse), but seldom with others aged 19–59 (8.7%; such as niece/nephew). About one-fifth have a maid(s) in the household (17.3%). Overall, older Singaporeans feel little loneliness or depression, have strong personal mastery, and have moderate social network support. Remarkably, older Singaporeans do not vary much in psychosocial features; top-quartile values are close to means, and coefficients of variation are small (Table 1 footnote). The majority of respondents rate their health as “average” (61.5%), and the majority have no vision or hearing difficulty (66.6%). Most have one or more chronic conditions (88.7%; mean 2.54) and half have some physical limitation (49.5%), but disability is uncommon (16.3% ADL, 21.1% IADL).

Receiving and giving help

For receiving help, most older Singaporeans received money from family members in the past year (80.8%) (Table 2). About half received material goods (45.7%), followed by emotional support/advice (35.9%), housework help (29.8%), IADL help (26.0%), and least often, ADL help (4.6%). For giving help, older Singaporeans were most likely to provide money to family members (38.7%; includes holiday gifts), followed by emotional support or advice (29.8%), babysitting grandchildren (18.9%), housework or cooking help (14.7%), and least often, material goods (9.8%) (Table 2).

Older Singaporeans typically receive help more than they give help. The difference (receive/give ratio) is about 2:1 for money and housework. For material goods, the difference is nearly 5:1. But for emotional support/advice, receiving and giving are coequal in frequency; the ratio is 1:1 (see “Discussion” section).

Bivariate links between receiving and giving help

Bivariate models use each receive help item to predict each give help item (30 regressions; Table 3). The great majority of effects linking receive and give are statistically significant (79%). The majority of those significant effects are positive (61%), thus in line with reciprocity. Two overall results stand out. (1) Older adults who receive tangible help are especially likely to give nontangible help. We call this “nontangibles for tangibles.” Specifically, older persons who receive money are much more likely, than those who do not, to help with babysitting grandchildren (OR = 1.69*) and help with housework (2.63***). Older persons who receive material goods are more likely to help with housework (2.98***) and give emotional support/advice (4.01***). Altogether, four of six (4/6) possible evaluations of “nontangible for tangibles” have significant OR > 1.00. That contrasts with: nontangibles for nontangibles, 5/12; tangibles for nontangibles, 2/8; and tangibles for tangibles, 2/4. (2) Older adults are likely to give the same type of help they have received. We call this “same for same.” Odds ratios are: receive housework help with give housework help 3.74***, emotional support/advice with same 23.45***, money with same 2.10***, and material goods with same 4.55***. All four possible evaluations of “same for same” have significant OR > 1.00.

We also estimated models using the set of five receive help items to predict each give help item (five regressions). We call them chunk models. Remarkably, results for significance, positive/negative odds ratios, and even size of odds ratios are very similar to the bivariate models (results available on request). The substantive findings about “nontangibles for tangibles” and “same for same” are repeated.

Multivariate links between receiving and giving help

Full multivariate models include all predictors for each give help item (five regressions; Table 4). We state reciprocity results first, then effects for the other predictors.

The majority of effects linking receive help and give help are statistically significant (55%). Further, the majority of those significant effects are positive (69%), thus in line with reciprocity. The substantive findings about “nontangibles for tangibles” and “same for same” are repeated. (1) Regarding “nontangibles for tangibles,” older adults who receive money are more likely, than those who do not, to help with babysitting grandchildren (OR = 1.71*). Those who receive material goods are more likely to babysit grandchildren (1.80***), help with housework/cooking (1.89***), and give emotional support/advice (1.92***). These results vary only a little from the initial bivariate models; thus, controls for other predictors have little impact. As earlier, four of six (4/6) evaluations of “nontangibles for tangibles” have significant OR > 1.00. The other combinations seldom have OR > 1.00: nontangibles for nontangibles, 4/12; tangibles for nontangibles, 1/8; tangibles for tangibles, 2/4. (2) Regarding “same for same,” older adults are likely to give the same type of help they received: receive housework help with give housework help (OR = 2.78***), emotional support/advice with same (19.93***), money with same (2.03***), and material goods with same (6.29***). “Same-for-same” effects are very similar to the initial bivariate models; they do not erode with inclusion of other predictors. Again, all four possible evaluations of “same for same” have significant OR > 1.00.

Some results go against reciprocity (31% of significant effects have OR < 1.00), such that when older persons receive help of a given type, they are unlikely to give help of another type. This occurs for receive housework with give babysit (OR = 0.57**), receive IADL care with give money (0.75*), receive emotional support/advice with give money (0.68***), the reverse tie of receive money with give emotional support/advice (0.62*), and receive money with give material goods (0.66*). These negative relationships appear in initial models and persist in full ones.

Some relationships between receive and give are nil (45% of all effects are nonsignificant), in that receiving X has no effect on giving Y. They deserve substantive scrutiny, but statistical chance and skewness can also play strong roles. Nil effects occur mainly for receive ADL/IADL help with all give help Y’s. The ADL/IADL items are highly skewed (low variation) and that is the likely reason for no detectable effects.

Other predictors (besides receive help) reflect older persons’ resources and abilities for giving help to family. Overall, their effects are less strong than expected. Only 38% of them are statistically significant, but the majority of those (73%) are in line with hypotheses. No predictor domain, such as sociodemographic or illness/disability, stands out with strong effects. Only two specific predictors have strong, consistent effects: age (giving help decreases with increasing age; 10/15 effects are significant) and ethnic group (Chinese are more likely than other groups to babysit and give material goods, and less likely to give emotional support/advice; 8/10 significant effects). Moderate (less strong, less consistent) effects occur for income adequacy (people with high- and low-income adequacy offer more help than those with just enough) and ADL/IADL disabilities (less giving as disability increases). But most predictors show weak, inconsistent results—few significant effects, some in line with hypothesis and some against it. Table 4 shows effects for all independent variables.

R2 (explained variance) were calculated for the bivariate models, chunk models, and full models. R2 values are tiny for bivariate models (range < .001–.076; exception of .325 for receive emotional support/advice with give emotional support/advice) (Table 4). Values increase for chunk models (.051–.099; and .366 for give emotional support/advice). Full models have R2 ranging .085–.435. The lowest value (.085) occurs for give money, the near-highest (.302) occurs for give housework/cooking, and the highest (.435) occurs for give emotional support/advice.

Discussion

We highlight the strength and types of family reciprocity in Singapore and then compare the results with a prior analysis (Verbrugge and Chan 2008).

Reciprocity

Reciprocity in older Singaporeans’ family relationships is common, taking two forms. One is “nontangibles for tangibles.” Older Singaporeans give services requiring time and effort to their family in return for money and material goods, as anticipated (Hypothesis 2). This aligns with contemporary Singapore circumstances. Older people typically have ample time but limited financial resources, whereas their family members (often midlife children) have more ample financial resources but limited time. There is also evidence of “same-for-same” reciprocity, such as giving money when money is received. Response bias is unlikely since receive help and give help questions are in separate sections, not adjacent. There are, in fact, good substantive reasons for same-for-same exchange in Singapore households: Housework can easily be task-sharing and done together. Also, people shop for food and other material goods for the whole family, so giving and receiving these is easily mutual. Other same-for-same exchanges are normative. Money gifts often occur on holidays, especially Lunar New Year, and are expected to be two way when possible. High reciprocity for support/advice reflects the fundamental nature of emotional intimacy; it is not one-sided, and is felt and practiced on both sides. This drives the high R2 values for models with emotional support/advice.

Our main reciprocity hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) was noncontingent; we thought all links between receive and give would be positive in final models! Negative links might occur initially, for example, if ill persons receive often but give rarely, but those links would turn positive when resources and health were controlled. The results are not so thorough (100%), but reciprocity does occur for the majority of receive help—give help links. Moreover, except for age and ethnic group, receive help is the strongest, most consistent predictor of giving help (Hypothesis 3). Remarkably, directions of initial bivariate links between receive and give stay steady in full models–positive links stay positive, and negative ones stay negative. Thus, reciprocity is a powerful aspect of older adults’ lives regardless of their resources and needs.

Other empirical analyses show positive ties between older persons’ receiving and giving help (review in Verbrugge and Chan 2008, p. 23). Recent studies also show positive receive–give ties (Cong and Silverstein 2008; Geurts et al. 2012; Isherwood et al. 2016; Lowenstein et al. 2007; Morgan et al. 1991 just found). The exchange of “nontangibles for tangibles” is also in the literature, specifically as “time for money” (review in Verbrugge and Chan 2008, p. 23). “Time for money” was the main result of the analysis just cited and is further demonstrated since then (Cong and Silverstein 2008; Leopold and Raab 2011; Shi 1993 just found). “Same for same” is not commonly studied. Its distinctive importance is best seen when compared to “not same” options, as done herein. Lin and Wu (2014) also compare same-for-same with other options. Older Americans who provided sick care and comfort to children expect to receive the same from their children when it is needed.

Strong negative links between receive and give help are substantively important. This analysis shows that two aspects: Some occur in a context of positive ties: when one exchange is very strong and positive, another in the same domain is weak. Specifically, two-way exchange money is common, but receiving money reduces chances of giving material goods. And housework reciprocity is common, but receiving housework help reduces chances of giving babysitting. Time and enthusiasm can run out; perhaps older people feel that enough has been given by sharing money and housework. Other negative links show that money and emotional support/advice are not compatible. When one is received, chances are low of giving the other. Money and intimacy apparently “cross swords” in social exchange.

Even nil results (nonsignificant links between receive and give) merit attention. Substantively, they suggest that certain types of help are unconnected. If repeated in other analyses, this means that some routes are quite closed in social exchange, and reciprocity motivations aim elsewhere. Statistical aspects (chance and skewness) can also play a role. The nil results herein suggest statistical rather than substantive reasons (see "Results" section).

The reciprocity results speak to classic Asian themes about family relationships: coresidence, filial piety, and intergenerational transfers.Footnote 4 First, older Singaporeans typically live with kin. The majority of Wave 2 respondents live with their children (66%), and nearly all live with any relatives (92%; includes spouse). Coresidence boosts chances of giving, receiving, and reciprocity behaviors. Still, coresidence is probably not a large factor for reciprocity in Singapore since small geography facilitates social exchanges with nonresident kin. Second, filial piety is strict feelings of obligations by adult children to their older parents for housing, income support, and illness/disability care. It is an abiding principle in Asian family relations (Mehta 1999; Mehta and Ko 2004). We cannot document motivations herein, but trust that filial piety is one of the underlying motives for older Singaporeans’ receiving help. Third, intergenerational transfers (IGT) research emphasizes flows of resources in families, “upward” from children to parents, and “downward” from parents to children. The sizes and timing of flows are estimated and compared, and consequences of transfers for individual well-being are studied. Reciprocity research differs; it is intrinsically about two-way exchanges, with symmetry as its essence and measure. Reciprocity is relevant in all social relations, not just family, and its consequences for network structure and social cohesion are considered. Still, the two fields intersect since both concern flows of goods and services. IGT researchers who read this analysis may appreciate the finding that help is often two-way (reciprocal), and certain forms of two-way exchange are common (tangibles for nontangibles, and same for same).

Replication

This analysis offers a fine opportunity to compare with a prior analysis of Singapore family exchanges (Verbrugge and Chan 2008). The PHASE Wave 2 data used here (for 2011) have targeted, well-designed items about family helping behaviors, whereas the prior data (for 1995/1999) were a potpourri of usable but not ideal items. The two analyses are closely similar in other respects (predictors, statistical techniques).

The time between the results is about 15 years. One’s first impulse is to see if family reciprocity has changed in frequency and types in Singapore. But the immense difference in survey items for the two data sets prohibits assessing change with any confidence. However, the analyses can be used successfully to assess replication of the main substantive findings. Do they come to the same conclusion about the shape of family ties?Footnote 5

Replication is not boring! It is a fundamental goal of scientific research, and often an explicit purpose of research in the biological and physical sciences, but seldom in the social sciences (Bronstein 1990; Earp and Trafimow 2015; Hüffmeier et al. 2016; Open Science Collaboration 2015; Schmidt 2009). This may be due, in part, to the impossibility of identical procedures in social research. But replication can be broadened to mean “similar findings,” and we now compare the two analyses from that perspective.

Their results are similar for significant receive–give ties, predictor effects, and explained variance.Footnote 6 Reciprocity is more evident in this analysis, probably due to targeted (rather than potpourri) items on social exchange. These similarities are welcome, but our key criterion for replication is whether reciprocity is substantively similar in the two analyses. The answer is yes. “Nontangibles for tangibles” (2011) encompasses “time for money” (1995/1999).Footnote 7 This is replication with elaboration. In both analyses, receiving help is a central predictor of giving help (at the top here; less prominent in the prior analysis, likely due to hodgepodge items). The motivation to reciprocate appears to be fundamental in family life, often exceeding impacts of other resources/needs on older persons’ helping behavior. In sum, we now have robust evidence about strength and forms of family reciprocity in Singapore.

Prospects for change

Will family reciprocity continue in its current form? Social circumstances for older persons are changing in Singapore. The older population is becoming more financially independent and literate. From 2000 to 2010, the percent of persons aged 65+ who rely on their children as the primary source of income decreased from 75 to 63% (Department of Statistics, Singapore 2001a, b, 2011). Older persons with no formal education decreased from 70% in 2000 to 60% in 2010. Singapore has an official policy of reliance on family for care of older persons (Chin and Phua 2016; Mehta 2006; Phua 2001; Teo 2004). The policy is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future, but program changes can help family members for contemporary communications, care planning, and safety of older kin.

As the social composition of older Singaporeans changes, and as families respond to government programs and incentives, family ties and exchanges are likely to change as well. Scientific buttress is small to date. Empirical research about Singapore family values, intergenerational transfers, and family social exchange, whether cross-sectional or over time, is not ample. Studies are mostly qualitative with small samples (Ingersoll-Dayton and Saengtienchai 1999; Mehta 1997, 1999; Mehta and Ko 2004; Mehta et al. 1995; Milagros et al. 1995; Phua and Loh 2008). There are few quantitative studies with sizable samples to date (Chan 1997; Gubhaju et al. 2018; Ofstedal et al. 1999; Teo and Mehta 2001). Overall, the research shows that commitment to family (filial piety) persists in contemporary Singapore. Authors expect it will continue but find new behavioral expression in the near future.

To document change in reciprocity will require population-based data with same or highly similar items over one or more decades. A new Singapore study has been launched (2016–2017) for persons aged 60+ that includes the same social exchange questions.Footnote 8 Using PHASE Wave 2 and the new survey, frequencies of receiving and giving help, and the nature of family reciprocity, can be compared over time. We expect that “nontangibles for tangibles” and “same for same” will persist for older persons, but more “tangibles for tangibles” exchanges will occur as their financial resources increase.

Conclusion

Older Singaporeans give time and effort (physical, mental, emotional) to their family in return for money and material goods received; this is “nontangibles for tangibles.” They also often give the same type of help that they received (“same for same”) due to social norms and the ease of task-sharing. Family reciprocity helps maintain and enhance social cohesion and goodwill as the state modernizes.

The Singapore data used here have a good array of behaviors in family social exchanges: babysitting grandchildren, housework and cooking, help with personal care, help going away from home, emotional support/advice, money, and food/clothes/other material goods. These are classic family behaviors in Asian societies. Not included are affective behaviors such as stating appreciation and gratitude, courtesy and listening, embracing or touching, and saying “I love you.” Also absent are modern-life behaviors, such as electronic communications, organizing appointments, handling paperwork, arranging house and property services, help with computers and mobile devices, and safety training. Western studies have included some of these affective and instrumental items (Geurts et al. 2012; Lin and Wu 2014; Morgan et al. 1991; Parrott and Bengtson 1999). They are not yet in Asian studies. Indeed, affective items may be difficult to include in Asia where traditionally, emotions are not readily expressed and public decorum is prized (including during interviews). Nevertheless, the scope of financial, instrumental, and affective behaviors in family ties is large and has always been so. Efforts to stretch questions toward affective and modern-life behaviors will give still better views of reciprocity in older people’s lives.

Notes

Other theories about giving and receiving behaviors, and their motivations, have been developed in economics, sociology, social psychology, and anthropology (Bengtson et al. 2005; Carstensen 1992; Emerson 1972a, b, 1981; Garrison 1984; Marcum and Koehly 2015; Mauss 1925; Ring 1996; Thomas 2010; Wu et al. 2016). They do not contradict social exchange and reciprocity, but approach social relations from other perspectives.

Motivations resist direct measurement. Surveys sometimes ask about perceptions and expectations, but not motives for actual behaviors. Experimental research tries to tap motivations by giving different games to study groups, then assessing the game-behavior differences and participant attitudes about their game-mates (Jung et al. 2014; Malmendier et al. 2014; Molm et al. 2007b).

These topics were reviewed in Verbrugge and Chan (2008, pp. 6–8). Recent research has some new directions (reference list is available on request): (1) coresidence of parents and their adult children is declining due to improved financial resources of older people, migration of adult children, more residence types with care services, and the ethos of late-life independence. On the other hand, coresidence is boosted by more time that contemporary unmarried adult children stay with their parents. (2) For filial piety, much is written about its "erosion" in Asia. Some studies query people's attitudes about filial piety. These suggest reshaping (not erosion) of filial piety, especially its behavioral expression. Helping behaviors are changing worldwide to include conscious affective displays of caring and love, finding and monitoring others to care for older parents, planning and administrative tasks, and assuring security. (3) For intergenerational transfers, new foci are their long-range stretch over years and geography, and their psychosocial impact on older persons (receiving and giving help act as buffers for stress and loneliness).

This matter has troubled some readers, so we provide a metaphor. The items differ, so we have "apples and pears". For social change, we need "apples and apples". For substantive replication, "apples and pears" are fine; we ask if they look and behave quite similarly as fruits.

Empirical comparison: Both analyses have high percentages of significant effects of receive help on give help (79% 2011; 86% 1995/1999). Of those, the percentage of positive ones is higher for 2011 (61%; 38% 1995/1999). Strength of other predictors (besides receive) is about the same (similar percentages of significant effects overall and per hypothesis). For predictors that appear in both analyses, direction of effects on give help is the same. Explained variance for models is higher in 2011 (.243 on average; .167 1995/1999). Prevalences of receive/give help cannot be compared for 2011 and 1995/1999 because items differ so much.

Substantive replication: We arranged the 1995/1999 items into nontangibles and tangibles. Positive links between receive and give are not very common in the prior analysis, but better for "nontangibles for tangibles" (4/12) than the other combinations (nontangibles for nontangibles, 0/12; tangibles for nontangibles, 1/2; tangibles for tangibles, 1/2). (Results are stronger for 2011: 4/6, 4/12, 1/8, and 2/4, respectively; see “Results” section.) Regarding "same for same", replication cannot be assessed. It could not be assessed in the prior analysis, because receive and give items were so different.

Transitions in Health, Employment, Social Engagement and Inter-Generational Transfers in Singapore Study (THE SIGNS Study), funded by the Singapore Ministry of Health.

References

Beel-Bates CA, Ingersoll-Dayton B, Nelson R (2007) Deference as a form of reciprocity among residents in assisted living. Res Aging 29:626–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027507305925

Bengtson VL, Putney NM, Johnson ML (2005) The problem of theory in gerontology today. In: Johnson ML (ed) The Cambridge handbook of age and ageing. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511610714.003

Blau PM (1964) Exchange and power in social life. Wiley, New York

Bronstein RF (1990) Publication politics, experimenter bias and the replication process in social science research. J Soc Behav Personal 5:71–81

Carstensen L (1992) Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol Aging 7:331–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.331

Chan A (1997) An overview of the living arrangements and social support exchanges of older Singaporeans. Asia Pac Popul J 12:35–50

Chin CWW, Phua K-H (2016) Long-term care policy: Singapore’s experience. J Aging Soc Policy 28:113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2016.1145534

Cong Z, Silverstein M (2008) Intergenerational time-for-money exchanges in rural China: does reciprocity reduce depressive symptoms of older grandparents? Res Hum Dev 5:6–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600701853749

Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Republic of Singapore (2001a) Census of Population 2000 statistical release 1: demographic characteristics. Release date July 2001. ISBN 981-04-4448-6

Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Republic of Singapore (2001b) Census of Population 2000 statistical release 2: education, language and religion. Release date October 2001. ISBN 981-04-4459-1

Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Republic of Singapore (2011) Census of Population 2010 statistical release 1: demographic characteristics, education, language and religion. Release date January 2011. ISBN 978-981-08-7808-5

Earp BD, Trafimow D (2015) Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Front Psychol 6:621. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00621

Emerson RM (1972a) Exchange theory, part I: a psychological basis for social exchange. In: Berger J, Zelditch M Jr, Anderson B (eds) Sociological theories in progress, vol 2. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston, pp 38–57

Emerson RM (1972b) Exchange theory, part II: exchange relations and networks. In: Berger J, Zelditch M Jr, Anderson B (eds) Sociological theories in progress, vol 2. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston, pp 58–87

Emerson RM (1981) Social exchange theory. In: Rosenberg M, Turner R (eds) Social psychology: sociological perspectives. Basic Books, New York, pp 30–65

Fingerman K, Miller L, Birditt K, Zarit S (2009) Giving to the good and the needy: parental support of grown children. J Marriage Fam 71:1220–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00665.x

Garrison RW (1984) Time and money: the universals of macroeconomic theorizing. J Macroecon 6:197–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0164-0704(84)90005-3

Geurts T, Poortman A-R, van Tilburg TG (2012) Older parents providing child care for adult children: does it pay off? J Marriage Fam 74:239–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00952.x

Gouldner AW (1960) The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am Sociol Rev 25:161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

Gubhaju, B, Chan A, Østbye T (2018) Intergenerational support to and from older Singaporeans. In: Yeung JW, Hu S (eds) Family and population change in Singapore: half a century of development and policies. Routledge, London

Homans GC (1961) Social behavior: its elementary forms. Harcourt, Brace and World, New York (Revised edition 1974)

Horioka CY, Gahramanov E, Hayat A, Tang X (2016) Why do children take care of their elderly parents? Are the Japanese any different? NBER Working paper No. 22245. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22245

Hüffmeier J, Mazei J, Schultze T (2016) Reconceptualizing replication as a sequence of different studies: a replication typology. J Exp Soc Psychol 66(S1):81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.09.009

Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT (2004) A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging 26:655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

Ingersoll-Dayton B, Saengtienchai C (1999) Respect for the elderly in Asia: stability and change. Int J Aging Hum Dev 48:113–130. https://doi.org/10.2190/G1XR-QDCV-JRNM-585P

Isherwood LM, Luszcz MA, King DS (2016) Reciprocity in material and time support within parent–child relationships during late-life widowhood. Ageing Soc 36:1668–1689. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000537

Jung Y, Hall J, Hong R, Goh T, Ong N, Tan T (2014) Payback: effects of relationship and cultural norms on reciprocity. Asian J Soc Psychol 17:160–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12057

Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J (1993) Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 5:179–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/089826439300500202

Kolm S-C (2008) Reciprocity. An economics of social relations. Cambridge University Press, New York

Kranton RE (1996) Reciprocal exchange: a self-sustaining system. Am Econ Rev 86:830–851. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2118307

Leopold T, Raab M (2011) Short-term reciprocity in late parent–child relationships. J Marriage Fam 73:105–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.174103737.2010.00792.x

Lin I-F, Wu H-S (2014) Intergenerational exchange and expected support among the young-old. J Marriage Fam 76:261–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12093

Lowenstein A, Katz R, Gur-Yaish N (2007) Reciprocity in parent-child exchange and life satisfaction among the elderly: a cross-national perspective. J Soc Issues 63:865–883. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00541.x

Lubben J (1988) Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam Community Health 11:42–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003727-198811000-00008

Lubben J, Gironda M (2004) Measuring social networks and assessing their benefits. In: Phillipson C, Allan G, Morgan DHJ (eds) Social networks and social exclusion: sociological and policy perspectives. Ashgate, Aldershot, pp 20–34

Malhotra R, Chan A, Malhotra C, Østbye T (2010) Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the elderly population of Singapore. Hypertens Res 33:1223–1231. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.177

Malmendier U, te Velde VL, Weber RA (2014) Rethinking reciprocity. Annu Rev Econ 6:849–874. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-041312

Marcum CS, Koehly LM (2015) Inter-generational contact from a network perspective. Adv Life Course Res 24:10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2015.04.001

Mauss M (1925) Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques. L’Année Sociologique, 1923–24. Alcan, Paris. English translation by Cunnison I (1954) The gift: forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. Cohen and West, London

Mehta K (1997) Respect redefined: focus group insights from Singapore. Int J Aging Hum Dev 44:205–219. https://doi.org/10.2190/8L57-YT6L-XQCL-8DDP

Mehta K (1999) Intergenerational exchanges: qualitative evidence from Singapore. Southeast Asian J Soc Sci 27:111–122. https://doi.org/10.1163/030382499X00075

Mehta KK (2006) A critical review of Singapore’s policies aimed at supporting families caring for older members. J Aging Soc Policy 18:43–57. https://doi.org/10.1300/J031v18n03_04

Mehta KK, Ko K (2004) Filial piety revisited in the context of modernizing Asian societies. Geriatr Gerontol Int 4:577–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2004.00157.x

Mehta K, Osman MM, Lee AEY (1995) Living arrangements of the elderly in Singapore: cultural norms in transition. J Cross Cult Gerontol 10:113–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00972033

Milagros MGA, Domingo L, Knodel J, Mehta K (1995) Living arrangements in four Asian countries: a comparative approach. J Cross Cult Gerontol 10:145–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00972034

Molm LD (1997) Risk and power use: constraints on the use of coercion in exchange. Am Sociol Rev 62:113–133. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657455

Molm LD (2003) Theoretical comparisons of forms of exchange. Sociol Theor 21:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9558.00171

Molm LD, Collett JL, Schaefer DR (2007a) Building solidarity through generalized exchange: a theory of reciprocity. Am J Sociol 113:204–242. https://doi.org/10.1086/517900

Molm LD, Schaefer DR, Collett JL (2007b) The value of reciprocity. Soc Psychol Quart 70:199–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250707000208

Morgan DL, Schuster RL, Butler EW (1991) Role reversals in the exchange of social support. J Gerontol B Psychol 46:S278–S287. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/46.5.s278

Ofstedal MB, Knodel J, Chayovan N (1999) Intergenerational support and gender: a comparison of four Asian countries. Southeast Asian J Soc Sci 27:21–42. https://doi.org/10.1163/030382499X00039

Open Science Collaboration (2015) Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349(6251):943. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Parrott TM, Bengtson RL (1999) The effects of earlier intergenerational affection, normative expectations, and family conflict on contemporary exchanges of help and support. Res Aging 21:73–105. https://doi.org/10.1086/517900

Pearlin LI, Schooler C (1978) The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav 19:2–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136319

Phua KH (2001) The savings approach to financing long-term care in Singapore. J Aging Soc Policy 13:169–183. https://doi.org/10.1300/j031v13n02_12

Phua VC, Loh J (2008) Filial piety and intergenerational co-residence: the case of Chinese Singaporeans. Asian J Soc Sci 36:659–679. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853108X327155

Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Mock SE, Sabir M, Pardo TB, Sechrist J (2007) Capturing the complexity of intergenerational relations: exploring ambivalence within later-life families. J Soc Issues 63:775–791. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00536.x

Purdam K, Tranmer M (2014) Expectations of being helped in return for helping—citizens, the state, and the local area. Popul Space Place 20:66–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1756

Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P (2001) A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol 27:85–95

Ring PS (1996) Fragile and resilient trust and their roles in economic exchange. Bus Soc 35:148–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039603500202

Rubin DB (1987) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, New York. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470316696

Schmidt S (2009) Shall we really do it again? The powerful concept of replication is neglected in the social sciences. Rev Gen Psychol 13:90–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015108

Shi L (1993) Family financial and household support exchange between generations: a survey of Chinese rural elderly. Gerontologist 33:468–480. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/33.4.468

Silverstein M, Conroy SJ, Gans D (2012) Beyond solidarity, reciprocity and altruism: moral capital as a unifying concept in intergenerational support for older people. Ageing Soc 32:1246–1262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000058X

Simmel G (1907) [Exchange]. In idem, Philosophie des geldes [Philosophy of wealth]. Duncker and Humblot, Leipzig, Germany, pp 33–61. English translation by Levine DN (1971) Georg Simmel: on individuality and social forms. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 43–69

Simmel G (1922) Die kreuzung sozialer kreise [The web of group affiliations]. In idem, Soziologie [Sociology]. Duncker and Humblot, Munich, Germany, pp 305–344. English translation by Wolff KH, Bendix R (1955) Conflict and the web of group affiliations. Free Press, New York, pp 125–195

StataCorp (2013) Stata statistical software: release 13. StataCorp LP, College Station, TX

Teo P (2004) Health care for older persons in Singapore: integrating state and community provisions with individual support. J Aging Soc Policy 16:43–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J031v16n01_03

Teo P, Mehta K (2001) Participating in the home: widows cope in Singapore. J Aging Stud 15:127–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(00)00022-0

Thomas PA (2010) Is it better to give or to receive? Social support and the well-being of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol 65B:351–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp113

Thomése F, van Tilburg T, Broese van Groenou M, Knipscheer K (2005) Network dynamics in later life. In: Johnson ML (ed) The Cambridge handbook of age and ageing. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511610714.049

Verbrugge LM, Chan A (2008) Giving help in return: family reciprocity by older Singaporeans. Ageing Soc 28:5–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X07006447

Wu T-F, Cross SE, Wu C-W, Cho W, Tey S-H (2016) Choosing your mother or your spouse: close relationship dilemmas in Taiwan and the United States. J Cross Cult Psychol 47:558–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115625837

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Angelique Chan, Director, Centre for Ageing Research and Education, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School for launching and overseeing the Panel on Health and Aging of Singaporean Elderly (PHASE) longitudinal study of older Singaporeans. The PHASE Wave 2 survey (2011) was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under its Singapore Translational Research Investigator Award, as part of the project “Establishing a Practical and Theoretical Foundation for Comprehensive and Integrated Community, Policy and Academic Efforts to Improve Dementia Care in Singapore” (P.I.: D. Matchar, NMRC-STAR-0005-2009). The authors gratefully acknowledge use of the services and facilities of the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan, funded by NICHD Center Grant P2CHD041028.

Funding

This analysis was conducted with no grant or contract funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The PHASE Wave 2 survey was reviewed and approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: M. J. Aartsen.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Verbrugge, L.M., Ang, S. Family reciprocity of older Singaporeans. Eur J Ageing 15, 287–299 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-017-0452-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-017-0452-1