Abstract

Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) are incidental findings that are being increasingly identified because of recent advancements in abdominal imaging technologies. PCLs include different entities, with each of them having a peculiar biological behavior, and they range from benign to premalignant or malignant neoplasms. Therefore, accurate diagnosis is important to determine the best treatment strategy. As transabdominal ultrasonography (US) is noninvasive, inexpensive, and widely available, it is considered to be the most appropriate imaging modality for the initial evaluation of abdominal diseases, including PCLs, and for follow-up assessment. We present a review of the possibilities and limits of US in the diagnosis of PCLs, the technical development of US, and the ultrasonographic characteristics of PCLs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) are frequent incidental findings during transabdominal ultrasonography (US) or other abdominal imaging studies [1]. The prevalence of PCLs has been reported to vary from 0.2 to 45.9% (Table 1) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Depending on the imaging method used, the detection rates of cysts vary as described above, with the reported detection rates being 2.1–5.4% for computed tomography (CT) [2,3,4,5,6], 0.21–3.5% for US [7, 8], 10–45.9% for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [3, 9,10,11,12,13,14], and 9.4–21.5% for endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) [15, 16].

PCLs involve different entities, with each of them having a peculiar biological behavior, and they range from benign to premalignant or malignant neoplasms [17, 18]. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms account for approximately 9–10% of PCLs [19, 20]. Serous neoplasms (SNs) and pseudocysts are benign lesions, but mucinous pancreatic cystic lesions are associated with a risk of malignancy, and either aggressive treatment or surveillance is required. Mucinous pancreatic cystic lesions can be classified into mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) [21]. IPMNs are the most common pancreatic cystic neoplasms, and they include a wide pathological spectrum of conditions, such as low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and invasive carcinoma. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant lesions is sometimes difficult. International consensus guidelines have been developed, and a flowchart of the treatment policy for branch duct-type IPMNs has been presented according to morphological features [22].

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer

In recent years, PCLs, particularly IPMNs, have been attracting attention as risk factors for pancreatic cancer. The risk of pancreatic cancer in people diagnosed with pancreatic cysts has been reported to be about 3–22.5 times higher than that in people without pancreatic cysts [13, 23,24,25,26]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify cases at risk of carcinogenesis from pancreatic cysts, and to closely observe these cases and intervene with early surgical treatment in cancerous cases. Additionally, pancreatic cysts have been shown to be associated with the presence of ductal adenocarcinoma elsewhere in the pancreas [13, 24]. Therefore, it should always be kept in mind that a pancreatic cyst might be an indirect finding of pancreatic cancer.

Transabdominal ultrasonography

As US is noninvasive, inexpensive, and widely available, it is considered to be the most appropriate imaging modality for the initial evaluation of pancreatic diseases including PCLs. The reported detection rate of PCLs is 0.21–3.5% for US [7, 8]. Additionally, the sensitivity of US for detecting pancreatic cysts has been reported to be 70.2–88.3% [27, 28]. The US detection rate was shown to be correlated with PCL location and size, as well as with patient sex, weight, and abdominal diameter [29, 30].

As the range to visualize the pancreatic area is reduced in obese individuals and in individuals with gastrointestinal gas, US might underestimate the existence of a PCL in these individuals. The pancreatic tail, in particular, is often difficult to assess by US [29, 30]. However, it becomes clearly observable on US after drinking 350 mL of liquid, as the liquid-filled stomach acts as an acoustic window. The sensitivity of this approach (92.2%) has been reported to be higher than that of routine upper abdominal US (70.2%) for the detection of PCLs [27].

PCLs have been shown to be associated with the presence of ductal adenocarcinoma elsewhere in the pancreas [13, 24]. If PCLs are found, the entire pancreas should be carefully observed using US to assess the presence of pancreatic cancer at other locations, and other abdominal imaging modalities might be necessary. Color Doppler US has been shown to contribute to the differential diagnosis of PCLs and vascular lesions [31,32,33]. On the other hand, it is difficult to show the normal intrapancreatic vessels with conventional Doppler imaging. However, superb microvascular imaging (SMI), a novel imaging modality that uses a special filtering technique, was developed to detect and visualize very slow blood flow not detected by conventional color Doppler imaging. Accordingly, SMI has recently been used to diagnose pancreatic diseases [33, 34].

Tissue harmonic imaging

Harmonic waves are generated by the non-linear propagation of ultrasound waves through body tissues. These beams have frequencies that are multiples of a fundamental transmitted frequency. In tissue harmonic imaging (THI) sonography, higher harmonic frequencies generated by propagation of an ultrasound beam through tissues are used instead of emitted US frequencies to produce a sonographic image. Presently, the second harmonic is being used to produce the sonographic image as the subsequent harmonics have decreasing amplitudes and are thus insufficient to generate a proper image. The following two methods have been developed for the generation of harmonic images: (1) a method involving harmonic band filtering of the fundamental component of the receiving signal and (2) a method involving phase inversion.

THI has several potential advantages [35]. First, the lateral resolution is improved. Second, reverberation artifacts and side-lobe artifacts are reduced. Third, the signal-to-noise ratio is improved. Fourth, the image quality is improved by better discrimination between liquid and solid structures, increasing spatial and contrast resolutions [36, 37]. Additionally, US images acquired by THI appear to be significantly clearer when compared with images acquired by fundamental B-mode imaging for PCLs (Fig. 1) [35, 38]. Therefore, THI is particularly useful for depicting PCLs [39]. THI should be considered in routine abdominal ultrasound examinations.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography

Microbubble contrast agents can provide information on parenchymal vasculature, including its microvasculature. US contrast agents are confined to the blood pool, whereas CT or MRI contrast agents are rapidly cleared into the extravascular space. As microbubble contrast agents used in contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) are approximately the size of red blood cells, they act as blood pool contrast agents. An advantage of CEUS is the ability to study the dynamics of lesions in real time. US contrast agents have very few allergic side effects, can be used in cases with liver and renal disorders, and have value with regard to safety. The excellent tolerance and safety profiles allow repeated examinations if needed [40]. Several studies have shown that transabdominal CEUS can be used to improve the identification, characterization, and staging of pancreatic diseases including PCLs [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. A previous study reported that the diagnostic accuracy of CEUS is comparable to that of MRI for the detection of septa and mural nodules in PCLs (Fig. 2) [49]. The diagnostic accuracy of CEUS using a classification diagnostic criterion is superior to that of conventional US and shows substantial agreement with that of enhanced CT [50]. CEUS can be used for the differential diagnosis of PCLs and as a follow-up imaging technique.

Cystic diseases of the pancreas

In the following text, the morphological and sonographic characteristics of PCLs are outlined (Table 2). Additionally, a solid tumor with cystic degeneration is briefly described as an important differential diagnosis.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

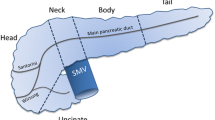

IPMNs are the most common pancreatic cystic neoplasms. They can be classified into branch duct type, main duct type, and mixed type. Main duct-type IPMNs require surgery because of high malignancy rates when the main pancreatic duct diameter is 10 mm or more (Fig. 3). Branch duct-type IPMNs are conditions mostly suspected as pancreatic cysts on diagnostic imaging. They are depicted as lobed and septal cystic lesions, but in reality, they involve dilation of the branched pancreatic duct.

IPMNs include a wide pathological spectrum of conditions, such as low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and invasive carcinoma. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant lesions is sometimes difficult. International consensus guidelines have been developed, and a flowchart of the treatment policy for branch duct-type IPMNs has been presented according to the morphological features [22]. The presence of high-risk stigmata indicates malignancy, and a cystic lesion of the head of the pancreas with obstructive jaundice, an enhancing mural nodule measuring 5 mm or more, and a main pancreatic duct diameter of 10 mm or more are important findings. If any of these are recognized, surgery is strongly recommended. On the other hand, worrisome imaging findings include a lesion size of 3 cm or more in diameter, thickening or contrasting of the cystic wall, a main pancreatic duct diameter of 5–9 mm, an abrupt change in the caliber of the pancreatic duct with distal pancreatic atrophy, lymphadenopathy and a cyst growth rate of 5 mm or more per year, and if any of these are recognized, EUS should be performed. Visualization of nodules on US is often difficult [51], and THI allows better evaluation of walls, septa, and mural nodules [39, 52]. CEUS can be of considerable help in the identification of mural nodules and septa in IPMNs. Mural nodules and septa are enhanced because of their vascularization [53]. On the other hand, mucin is not enhanced. Therefore, CEUS can improve the differential diagnosis between mural nodules and mucin. In addition, it has been reported that quantitative evaluation of echogenicity after intravenous injection of IPMNs is closely related to the malignancy of IPMNs [47, 54].

Pancreatic fibrosis or fibrosing reactions have been reported in IPMN [55, 56]. Ultrasound elastography is a possible method for noninvasively evaluating pancreatic fibrosis [57,58,59]. It was reported that elastography measurement of the background pancreatic parenchyma by US was useful for diagnosing the presence of BD-IPMN [60].

Current issues in the management of branch duct-type IPMNs include the selection of candidates for surgical resection and the development of intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma during follow-up of an IPMN that was not resected [26, 61, 62]. Another issue is the occurrence of a ductal carcinoma of the pancreas concomitantly with an IPMN during follow-up of the IPMN [63,64,65].

EUS is useful for surveillance of patients with IPMNs to assess the potential development of concomitant ductal carcinoma of the pancreas [66, 67]. As IPMNs have a long clinical course, follow-up methods should be feasible and tolerable for patients and should have a reliable diagnostic ability. US is reasonable as a follow-up method from a clinical point of view, although it has obvious limitations with regard to diagnostic ability [62]. Ideally, a combination of US and EUS, CT, or MRI is recommended at present; however, there is no consensus on the best approach for combining US with EUS, CT, or MRI.

Future prospective studies are necessary to determine the optimal surveillance strategy (intervals and imaging modalities) for branch duct-type IPMNs.

Mucinous cystic neoplasm

MCNs have an estrogen or progesterone receptor-positive ovarian-like stroma and usually occur in women. They often occur in the body and tail of the pancreas. Although the malignancy grade is not high, these tumors can eventually become malignant, and surgery is the preferred approach if the procedure is tolerable [21]. MCNs are typically macrocystic tumors 2 cm or more in diameter. Although MCNs are usually unilocular cystic lesions, septa have been observed within the cyst in some cases, and the area partitioned by the septum is visualized as a cyst (cyst in cyst). A mural nodule might be found in the cyst. The cystic content can be nonhomogeneous owing to the presence of mucin or intralesional hemorrhage (independent cyst). Generally, there is no communication with the pancreatic duct and no dilation of the main pancreatic duct. Small MCNs with diameters of only a few millimeters have been noted. The definitive diagnosis of small MCNs from images alone is difficult, and they are often confused with IPMNs. In such cases, follow-up observation focused on worrisome features and high-risk stigmata should be selected; however, according to the American Gastroenterological Association Institute guidelines, the significance of discrimination between IPMN and MCN is low [68]. Evidence of malignancy includes the presence of cystic wall irregularity and thickening, a mural nodule, or an adjacent solid mass (Fig. 4).

Serous neoplasm

As few SNs are malignant, they often do not require surgical resection, and follow-up is selected in asymptomatic patients [69]. The most common appearance is an irregularly contoured sphere involving a multilocular tumor composed of many microcystic components inside (Fig. 5). This appearance was first described by Compagno and Oertel [70] as a “honeycomb.” There might be macrocysts (less than 2 cm) at the margin of the tumor. Additionally, central fibrosis or calcification might be seen [71]. In some SNs, US shows a solid mass owing to the presence of a large number of very small cysts delimited by septa [72, 73]. Additionally, uncommonly, SNs might have an oligolocular or macrocystic appearance and/or no central scar. In these cases, differentiation from other cystic or solid neoplasms of the pancreas can be difficult. Doppler signals might be observed in the solid component and septa on Doppler US. The CEUS findings of SNs include septal enhancement and massive enhancement (homogeneous enhancement within the solid component of the tumor and an irregular shape) [74].

Pseudocyst

Pseudocysts can arise as a complication of acute pancreatitis. These cysts are fibrous-walled anechoic structures without an epithelial lining. Inflammatory cysts have been referred to as so-called pseudocysts. Recently, the revised Atlanta classification has made it possible to divide cysts into pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis (WON) [75].

Pseudocysts vary in size and shape. They are often unilocular, but might have internal septa-like structures. Their walls are thick, and they might have high echoic debris internally. Pseudocysts can be difficult to distinguish from pancreatic cystic neoplasms, especially when they contain debris. CEUS has been reported to improve the characterization of pseudocysts [76, 77]. Pseudocysts appear anechoic because of the absence of vessels. Rices and Wermke [77] reported that the sensitivity and specificity of CEUS for the diagnosis of pseudocysts were both 100% among nine patients with pseudocysts.

Solid pancreatic tumor with cystic degeneration

Solid pancreatic tumors, such as solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs), pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PNENs), and invasive ductal carcinomas (IDCs), might occasionally cause cystic degeneration and manifest as cystic lesions [78, 79]. Thus, solid tumors with cystic degeneration should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas, although their prevalence is very low when compared with that of true pancreatic cystic neoplasms.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm

SPNs typically occur in young women (mean age of approximately 30 years). They usually start as solid tumors and cause cystic degeneration, resulting in a cystic appearance on US owing to hemorrhagic necrosis (Fig. 6) [80]. On US, SPNs typically appear as well-demarcated tumors with a combination of solid and cystic areas, and they might have eggshell-like or linear-like calcification. The atypical pure fluid forms are difficult to differentiate from MCNs.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. a US shows a cystic mass with a thick wall and septum at the pancreatic tail. b The cut surface shows solid and cystic content surrounded by a fibrous capsule. c Low-magnification micrograph of hematoxylin and eosin staining shows pseudopapillae surrounded by non-cohesive neoplastic cells

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm

Many PNENs are delineated as well-defined round lesions with a homogenous internal echo. However, cystic degeneration is sometimes noted with the unilocular form. In previous investigations of resected pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, approximately 5–10% showed cystic degeneration [81, 82], and a high rate of 17% has also been reported [83]. A larger tumor size is considered to be associated with a higher rate of cystogenesis [83]. Additionally, it has been suggested that PNENs with cystic degeneration should be considered histologically different from PNENs without cystic degeneration and that they should be considered as low-grade independent subgroups [84, 85]. Although there is no clear mechanism of cystic degeneration, it is presumed to be associated with a tumor circulatory disorder and intratumoral hemorrhage. Cystic PNENs do not appear to have any typical US findings that can be used to distinguish them from other pancreatic cystic lesions (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, on US, cystic PNENs might show a pure cystic or mixed solid-cystic component, a more frequent unilocular form than multilocular form, and a thicker cystic wall (> 2 mm) when compared with MCNs [86].

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm. a US shows a cystic mass with a marked thick wall at the pancreatic head. b The cut surface shows a solid lesion and cystic degeneration with coagulation. c High-magnification micrograph of hematoxylin and eosin staining shows sheets of small round cells with rich fibrovascular stroma

Invasive ductal carcinoma

It has been reported that IDCs can cause cystic degeneration [87,88,89,90]. A pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) typically presents as an infiltrative hypoechoic solid mass. However, it has been reported that approximately 8% of PDACs have an intratumoral cystic appearance or show accompanying non-neoplastic cystic lesions in contact with the tumor [87]. The histopathologic findings of PDACs with cystic features are largely divided into neoplastic cystic and non-neoplastic cystic findings. Neoplastic cystic findings include large duct-type cysts, neoplastic mucin cysts, and colloid carcinomas formed by the neoplastic glands themselves and degenerative cystic changes usually associated with hemorrhagic tumor necrosis. Non-neoplastic cystic findings include retention cysts caused by ductal obstruction and pseudocysts caused by tumor-associated pancreatitis [88]. PDACs with degenerative cystic changes should be differentiated from SPNs and cystic PNENs. A combined retention cyst or pseudocyst might delay the diagnosis of PDACs as a small hypoechoic solid tumor can be masked by a large cystic lesion. PDACs should be considered in the differential diagnosis of PCLs.

Other IDCs, such as undifferentiated carcinomas with osteoclast-like giant cells [89] and adenosquamous carcinomas (Fig. 8) [90], might show bleeding and necrosis inside the tumor and cause cystic degeneration.

Conclusion

US is established as the most appropriate imaging modality for the initial evaluation of pancreatic diseases, including PCLs, as it is widely available, noninvasive, and inexpensive. In addition, new techniques, such as THI and CEUS, could contribute to the differential diagnosis of PCLs.

References

Zerboni G, Signoretti M, Crippa S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: prevalence of incidentally detected pancreatic cystic lesions in asymptomatic individuals. Pancreatology. 2019;19:2–9.

Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:802–7.

Ip IK, Mortele KJ, Prevedello LM, et al. Focal cystic pancreatic lesions: assessing variation in radiologists’ management recommendations. Radiology. 2011;259:136–41.

Zanini N, Giordano M, Smerieri E, et al. Estimation of the prevalence of asymptomatic pancreatic cysts in the population of San Marino. Pancreatology. 2015;15:417–22.

Ippolito D, Allegranza P, Bonaffini PA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 256-detector row computed tomography in detection and characterization of incidental pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:707546.

Chang YR, Park JK, Jang JY, et al. Incidental pancreatic cystic neoplasms in an asymptomatic healthy population of 21,745 individuals: large-scale, single-center cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5535.

Ikeda M, Sato T, Morozumi A, et al. Morphologic changes in the pancreas detected by screening ultrasonography in a mass survey, with special reference to main duct dilatation, cyst formation, and calcification. Pancreas. 1994;9:508–12.

Soroida Y, Sato M, Hikita H, et al. Pancreatic cysts in general population on ultrasonography: prevalence and development of risk score. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:1133–40.

Moris M, Bridges MD, Pooley RA, et al. Association between advances in high-resolution cross-section imaging technologies and increase in prevalence of pancreatic cysts from 2005 to 2014. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e3.

Girometti R, Intini S, Brondani G, et al. Incidental pancreatic cysts on 3D turbo spin echo magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: prevalence and relation with clinical and imaging features. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:196–205.

Zhang XM, Mitchell DG, Dohke M, et al. Pancreatic cysts: depiction on single-shot fast spin-echo MR images. Radiology. 2002;223:547–53.

Lee KS, Sekhar A, Rofsky NM, et al. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2079–84.

Matsubara S, Tada M, Akahane M, et al. Incidental pancreatic cysts found by magnetic resonance imaging and their relationship with pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2012;41:1241–6.

Kromrey ML, Bülow R, Hübner J, et al. Prospective study on the incidence, prevalence and 5-year pancreatic-related mortality of pancreatic cysts in a population-based study. Gut. 2018;67:138–45.

Sey MS, Teagarden S, Settles D, et al. Prospective cross-sectional study of the prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts during routine outpatient endoscopic ultrasound. Pancreas. 2015;44:1130–3.

Martínez B, Martínez JF, Aparicio JR. Aparicio, prevalence of incidental pancreatic cyst on upper endoscopic ultrasound. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31:90–5.

Fernández-del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer SP, et al. Incidental pancreatic cysts: clinicopathologic characteristics and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg. 2003;138:427–34 [discussion 433–434].

Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1218–26.

Johnson CD, Stephens DH, Charboneau JW, et al. Cystic pancreatic tumors: CT and sonographic assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:1133–8.

Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1934–43.

Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–32.

Tanaka M, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738–53.

Tada M, Kawabe T, Arizumi M, et al. Pancreatic cancer in patients with pancreatic cystic lesions: a prospective study in 197 patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1265–70.

Tanaka S, Nakao M, Ioka T, et al. Slight dilatation of the main pancreatic duct and presence of pancreatic cysts as predictive signs of pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Radiology. 2010;254:965–72.

Chernyak V, Flusberg M, Haramati LB, et al. Incidental pancreatic cystic lesions: is there a relationship with the development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma and all-cause mortality? Radiology. 2015;274:161–9.

Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Kawashima H, et al. Natural history of pancreatic cystic lesions: a multicenter prospective observational study for evaluating the risk of pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:320–8.

Nakao M, Katayama K, Fukuda J, et al. Evaluating the ability to detect pancreatic lesions using a special ultrasonography examination focusing on the pancreas. Eur J Radiol. 2017;91:10–4.

Jeon JH, Kim JH, Joo I, et al. Transabdominal ultrasound detection of pancreatic cysts incidentally detected at CT, MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210:518–25.

Sun MRM, Strickland CD, Tamjeedi B, et al. Utility of transabdominal ultrasound for surveillance of known pancreatic cystic lesions: prospective evaluation with MRI as reference standard. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:1180–92.

Sumi H, Itoh A, Kawashima H, et al. Preliminary study on evaluation of the pancreatic tail observable limit of transabdominal ultrasonography using a position sensor and CT-fusion image. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:1324–31.

Gandolfi L, Torresan F, Solmi L, et al. The role of ultrasound in biliary and pancreatic diseases. Eur J Ultrasound. 2003;16:141–59.

Bertolotto M, D’Onofrio M, Martone E, et al. Ultrasonography of the pancreas. 3. Doppler imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:161–70.

Yamanaka Y, Ishida H, Naganuma H, et al. Superb microvascular imaging (SMI) findings of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm: a report of two cases. J Med Ultrason. 2001;2018:515–23.

Tokodai K, Miyagi S, Nakanishi C, et al. The utility of superb microvascular imaging for monitoring low-velocity venous flow following pancreas transplantation: report of a case. J Med Ultrason. 2001;2018:171–4.

Hohl C, Schmidt T, Honnef D, et al. Ultrasonography of the pancreas. 2. Harmonic imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:150–60.

Shapiro RS, Wagreich J, Parsons RB, et al. Tissue harmonic imaging sonography: evaluation of image quality compared with conventional sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1203–6.

Choudhry S, Gorman B, Charboneau JW, et al. Comparison of tissue harmonic imaging with conventional US in abdominal disease. Radiographics. 2000;20:1127–35.

Littmann M, Schwaiger U, Sczepanski B, et al. Improved ultrasound imaging of the pancreas with the transsplenic view and tissue harmonic imaging. Ultraschall Med. 2001;22:163–6.

Hohl C, Schmidt T, Haage P, et al. Phase-inversion tissue harmonic imaging compared with conventional B-mode ultrasound in the evaluation of pancreatic lesions. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:1109–17.

Sidhu PS, Cantisani V, Dietrich CF, et al. The EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations for the clinical practice of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in non-hepatic applications: update 2017 (short version). Ultraschall Med. 2018;39:154–80.

Takeda K, Goto H, Hirooka Y, et al. Contrast-enhanced transabdominal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pancreatic mass lesions. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:103–6.

Kitano M, Kudo M, Maekawa K, et al. Dynamic imaging of pancreatic diseases by contrast enhanced coded phase inversion harmonic ultrasonography. Gut. 2004;53:854–9.

Rickes S, Malfertheiner P. Echo-enhanced sonography–an increasingly used procedure for the differentiation of pancreatic tumors. Dig Dis. 2004;22:32–8.

Beyer-Enke SA, Hocke M, Ignee A, et al. Contrast enhanced transabdominal ultrasound in the characterisation of pancreatic lesions with cystic appearance. JOP. 2010;11:427–33.

Rickes S, Mönkemüller K, Malfertheiner P. Echo-enhanced ultrasound with pulse inversion imaging: a new imaging modality for the differentiation of cystic pancreatic tumours. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2205–8.

D’Onofrio M, Barbi E, Dietrich CF, et al. Pancreatic multicenter ultrasound study (PAMUS). Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:630–8.

Vasile TA, Socaciu M, Stan Iuga R, et al. Added value of intravenous contrast-enhanced ultrasound for characterization of cystic pancreatic masses: a prospective study on 37 patients. Med Ultrason. 2012;14:108–14.

Fukuda J, Tanaka S, Ishida N, et al. A case of stage IA pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma accompanied with focal pancreatitis demonstrated by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. J Med Ultrason. 2001;2018:617–22.

D’Onofrio M, Megibow AJ, Faccioli N, et al. Comparison of contrast-enhanced sonography and MRI in displaying anatomic features of cystic pancreatic masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:1435–42.

Fan Z, Yan K, Wang Y, et al. Application of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in cystic pancreatic lesions using a simplified classification diagnostic criterion. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:974621.

Lü K, Dai Q, Xu ZH, et al. Ultrasonographic characteristics of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Chin Med Sci J. 2010;25:151–5.

Hammond N, Miller FH, Sica GT, et al. Imaging of cystic diseases of the pancreas. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1243–62.

D’Onofrio M, Caffarri S, Zamboni G, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in the characterization of pancreatic mucinous cystadenoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:1125–9.

Itoh T, Hirooka Y, Itoh A, et al. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced transabdominal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:144–52.

Loftus EV Jr, Olivares-Pakzad BA, Batts KP, et al. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas: clinicopathologic features, outcome, and nomenclature. Members of the pancreas clinic, and pancreatic surgeons of mayo clinic. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1909–18.

Kakizaki Y, Makino N, Tozawa T, et al. Stromal fibrosis and expression of matricellular proteins correlate with histological grade of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2016;45:1145–52.

Shiina T. JSUM ultrasound elastography practice guidelines: basics and terminology. J Med Ultrason. 2001;2013:309–23.

Hirooka Y, Kuwahara T, Irisawa A, et al. JSUM ultrasound elastography practice guidelines: pancreas. J Med Ultrason. 2001;2015:151–74.

Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Kawashima H, et al. Feasibility and usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided shear-wave measurement for assessment of autoimmune pancreatitis activity: a prospective exploratory study. J Med Ultrason. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-019-00944-4.

Koya T, Kawashima H, Ohno E, et al. Increased hardness of the underlying pancreas correlates with the presence of intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm in a limited number of cases. J Med Ultrason. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-019-00956-0.

Maguchi H, Tanno S, Mizuno N, et al. Natural history of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a multicenter study in Japan. Pancreas. 2011;40:364–70.

Yamaguchi T, Baba T, Ishihara T, et al. Long-term follow-up of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas with ultrasonography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1136–43.

Uehara H, Nakaizumi A, Ishikawa O, et al. Development of ductal carcinoma of the pancreas during follow-up of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Gut. 2008;57:1561–5.

Tanno S, Nakano Y, Koizumi K, et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas in long-term follow-up patients with branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Pancreas. 2010;39:36–40.

Mandai K, Uno K, Nakase K, et al. Association between hyperechogenic pancreas and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma concomitant with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. J Med Ultrason. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-019-00949-z.

Kamata K, Kitano M, Kudo M, et al. Value of EUS in early detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas in patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2014;46:22–9.

Torisu Y, Takakura K, Kinoshita Y, et al. Pancreatic cancer screening in patients with presumed branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. World J Clin Oncol. 2019;10:67–74.

Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, et al. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819–22 [quize 12–13].

Compton CC. Serous cystic tumors of the pancreas. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:43–55.

Compagno J, Oertel JE. Microcystic adenomas of the pancreas (glycogen-rich cystadenomas): a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:289–98.

Torresan F, Casadei R, Solmi L, et al. The role of ultrasound in the differential diagnosis of serous and mucinous cystic tumours of the pancreas. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:169–72.

Lewin M, Hoeffel C, Azizi L, et al. Imaging of incidental cystic lesions of the pancreas. J Radiol. 2008;89:197–207.

Yasuda A, Sawai H, Ochi N, et al. Solid variant of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:353–5.

Chen F, Liang JY, Zhao QY, et al. Differentiation of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms from serous cystadenomas of the pancreas using contrast-enhanced sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:449–55.

Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–11.

D’Onofrio M, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of the pancreas. Jop. 2007;8:71–6.

Rickes S, Wermke W. Differentiation of cystic pancreatic neoplasms and pseudocysts by conventional and echo-enhanced ultrasound. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:761–6.

Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Peters K, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas and tumor-like lesions with cystic features: a review of 418 cases and a classification proposal. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:168–78.

Paik KY, Choi SH, Heo JS, et al. Solid tumors of the pancreas can put on a mask through cystic change. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:79.

Tipton SG, Smyrk TC, Sarr MG, et al. Malignant potential of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2006;93:733–7.

Volkan Adsay N. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:S71–93.

Kongkam P, Al-Haddad M, Attasaranya S, et al. EUS and clinical characteristics of cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopy. 2008;40:602–5.

Bordeianou L, Vagefi PA, Sahani D, et al. Cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: a distinct tumor type? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1154–8.

Koh YX, Chok AY, Zheng HL, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinicopathologic characteristics of cystic versus solid pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Surgery. 2014;156:e2.

Singhi AD, Chu LC, Tatsas AD, et al. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1666–73.

Yoon WJ, Daglilar ES, Pitman MB, et al. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: endoscopic ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration characteristics. Endoscopy. 2013;45:189–94.

Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Anlauf M, et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas with cystic features: neither rare nor uniform. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1157–64.

Youn SY, Rha SE, Jung ES, et al. Pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma with cystic features on cross-sectional imaging: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2018;24:5–11.

Oehler U, Jürs M, Klöppel G, et al. Osteoclast-like giant cell tumour of the pancreas presenting as a pseudocyst-like lesion. Virchows Arch. 1997;431:215–8.

Colarian J, Fowler D, Schor J, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with cystic degeneration. South Med J. 2000;93:821–2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Ethical statements

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashimoto, S., Hirooka, Y., Kawabe, N. et al. Role of transabdominal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. J Med Ultrasonics 47, 389–399 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-019-00975-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-019-00975-x