Abstract

Background

Basic life support (BLS) is one of the most efficient ways to improve out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) victims’ outcomes. Resuscitation initiated by a random witness of OHCA is essential to increase the chances of survival.

Aim

To assess the impact of BLS training in cardiac patients on knowledge about first aid for OHCA.

Materials and methods

The study group consisted of 68 participants who completed a questionnaire prior to BLS training. Forty-three of them then filled out the same questionnaire again after the BLS course. Participants’ knowledge was assessed with a self-designed questionnaire, which comprised 41 questions divided into six domains, namely legal aspects, resuscitation technique, resuscitation algorithm, knowledge about using an automated external defibrillator (AED), “calling for help” knowledge and identifying sudden cardiac arrest.

Results

The average score before the BLS course was lower compared with final results (43.8% ± 15.6% vs. 68.6% ± 22.7% [% of max. score], p = 0.001). The best scores, both before and after the BLS course, were gained in the “calling for help” knowledge (79.5% ± 33.5% vs. 80.4% ± 17.4% [% of max. score], p = 0.5) and “knowledge about using AEDs” domains (62.4% ± 35.2% vs. 74.7% ± 29.3% [% of max. score], p = 0.1). Patients who completed first aid courses gained better scores in the “knowledge about using an AED” domain (93.3% ± 14.9% vs. 58.6% ± 35.4% [% of max. score], p = 0.02). No differences between the other domains and overall scores were reported (total score: 48% ± 12% vs. 42% ± 17.5% [% of max. score], p = 0.5).

Conclusion

General knowledge about BLS is poor. BLS training in cardiac patients improves knowledge about first aid for OHCA. Education and hands-on training are crucial to improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. The average incidence among adults is approximately 75–96 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year (Berdowski et al. 2010; Luc et al. 2019). The predominant cause of OHCA in developing countries is cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Davies and Thomas 1984; Engdahl et al. 2002). Despite a decrease in the incidence of CVD and better diagnostic and therapeutic methods, outcomes after OHCA remain poor. On average, every tenth patient who suffers from OHCA survives to discharge but most of these patients are cognitively impaired, especially in terms of memory, attention deficits, and executive functioning (Atwood et al. 2005; Berdowski et al. 2010; Hawkes et al. 2017; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska et al. 2018). The most effective way to improve survival is early recognition of cardiac arrest and immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with early defibrillation given by bystanders (Bobrow et al. 2010; Han et al. 2019; Iwami et al. 2009, 2012; Valenzuela et al. 2000). The European Resuscitation Council (ERC) has developed Basic Life Support (BLS) guidelines, which provide lifesaving procedures that can be used even by lay people until cardiac arrest victims can be given professional medical care. Unfortunately, many bystanders do not provide CPR (Bouland et al. 2017; Krammel et al. 2018; Nurnberger et al. 2013). Previous studies have demonstrated that overall population knowledge about BLS and first aid is relatively poor (Özbilgin et al. 2015; Rajapakse et al. 2010). While it has been shown that BLS training improves knowledge, CPR quality, awareness and willingness to help OHCA victims (Lund-Kordahl et al. 2019; Pehlivan et al. 2019; Villalobos et al. 2019); however, there is a paucity of data regarding BLS knowledge and BLS training among cardiac patients. Thus, we sought to evaluate the impact of BLS training in cardiac patients on knowledge about first aid for OHCA.

Methods

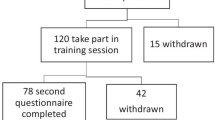

The study group consisted of 68 patients with stable angina admitted to the Department of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, University Hospital in Krakow for elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Before discharge, all patients filled out a questionnaire, which was administered with explanations by trained medical researcher. Then, two weeks after discharge, the BLS course was conducted by a certified ERC instructor. After training, participants were asked to fill out the questionnaire again. The questionnaire comprised 41 questions, the first 16 relating to general information such as age, sex, marital status, education, participation in first aid courses in the past, attitude to providing CPR and opinion about compulsory BLS courses. The second section consisted of 25 exam questions, each with only one correct answer. The questionnaire was divided into six domains covering legal aspects, resuscitation technique, resuscitation algorithm knowledge, knowledge about using AEDs, “calling for help” knowledge, and identifying sudden cardiac arrest. BLS training as well as the self-designed questionnaire were prepared based on the current ERC guidelines (Perkins et al. 2018). Signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Standard descriptive statistical methods were used. The normality of the data was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Quantitative variables were described using means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as percentages and a direct comparison between the groups was done using the Chi-square test. One-way analysis with unpaired two-sample T-tests (for normal distribution) or the Mann–Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed data) was applied for quantitative variables. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted with STATISTICA version 13 software (StatSoft Inc., Krakow, Poland).

Results

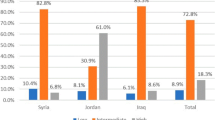

The majority of participants were married (57.4%), female (72%), pensioners (86.8%), and with a higher level of education (73.5%) — Table 1. Only around every tenth respondent (8.9%) had attended a first aid course in the past. The main reasons for non-participation were lack of BLS courses in the neighborhood (33.8%) and fear of providing first aid (20.5%). The vast majority believed that first aid course participation should be compulsory for adults and would like to take part in BLS training themselves in the future (95.6% and 97.1%, respectively). Although more than half of the participants rated their knowledge of first aid for OHCA as “good” (52.9%), on the other hand, most stated that population’s knowledge of first aid for OHCA is insufficient (94.1%). Only 19.1% had ever been witnesses of CPR provided to OHCA victims, and none had performed it personally (Table 2). Of all included patients, 39.7% declared they would not start CPR during OHCA before BLS training. There was no increase in terms of willingness to provide first aid after BLS training (Table 3). As presented in Table 4, higher total scores were observed after BLS training (43.8% ± 15.6% vs. 68.6% ± 22.7% [% of max. score], p = 0.001). The best pre- and post-course scores were for the “calling for help” knowledge (79.5% ± 33.5% vs. 80.4% ± 17.4% [% of max. score], p = 0.5) and “knowledge about using AEDs” domains (62.4% ± 35.2% vs. 74.7% ± 29.3% [% of max. score], p = 0.1). Moreover, participants who had attended previous first aid courses prior to the study gained better scores in the pre-training questionnaire for “knowledge about using AEDs” (93.3% ± 14.9% vs. 58.6% ± 35.4% [% of max. score], p = 0.02) with no differences between the remaining domains and overall score. Participants who agreed with compulsory first aid courses had significantly better scores in “resuscitation technique” and “resuscitation algorithm knowledge” and better overall scores compared to those who disagreed (34.5% ± 18.1% vs. 5.6% ± 7.9% [% of max. score], p = 0.04; 36.5% ± 17.1% vs. 8.3% ± 11.8% [% of max. score], p = 0.04; 45.2% ± 14.4% vs. 13.3% ± 16.2% [% of max. score], p = 0.01, respectively). Interestingly, patients who believed that levels of knowledge about BLS among adults is generally adequate had significantly worse results in “resuscitation algorithm knowledge” (11.1% ± 19.3% vs. 37.1% ± 16.7% [% of max. score], p = 0.04). However, there was no difference in terms of their overall score (23.0% ± 22.5% vs. 45.0% ± 14.9% [% of max. score], p = 0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that overall knowledge about first aid for cardiac arrest victims is not satisfactory. The average score from our self-designed questionnaire before BLS training was only 10.9 ± 3.9 points with 43.8% correct answers. However, participation in first aid courses improves knowledge about first aid for OHCA. Our results are consistent with other studies suggesting insufficient levels of knowledge in the general population (Goniewicz et al. 2002; Özbilgin et al. 2015; Rajapakse et al. 2010). In our study, only 8.9% of all participants had attended first aid courses in the past. However, our results contradict those of a study conducted in Poland in 2000 suggesting that approximately 75% of the Polish population has received CPR training (Rasmus and Czekajlo 2000). The most popular sources of knowledge about first aid are obligatory CPR training in workplaces, driving schools, secondary and high schools. However, those courses are insufficient due to scarce training time. The inability to gain knowledge and experience was mainly related to a lack of opportunities to take part in first aid training. This shortcoming also seems to be the main reason for the variance and low levels of knowledge about first aid found in our study group. A low level of knowledge about first aid for OHCA was also related to attitude to applying CPR. In a previous study, the majority of individuals who were witnesses of sudden cardiac arrest hesitated to perform CPR mainly due to a lack of proper knowledge and fear of making a mistake (Özbilgin et al. 2015). We observed similar results in our study. Before the BLS course, most participants were hesitant and nearly 40% said they would not start CPR for OHCA. On the other hand, nearly all the participants agreed with obligatory first aid courses and would also like to train their own BLS skills. Our study revealed that BLS training in cardiac patients significantly improves knowledge about first aid in OHCA. Similar results in other populations have been observed in multiple studies (Lund-Kordahl et al. 2019; Mohamed 2017; Villalobos et al. 2019; Wingen et al. 2018). We observed improvement of knowledge in all domains of first aid in OHCA. Before and after BLS training, participants scored best for “calling for help” and AED usage. The common emergency telephone number in the European Union is “112” and has been advertised in the media as a universal call number for all emergency units for several years now. A similarly high profile can be observed for AEDs, which can be found in many public places and are advertised in social campaigns. The worst results were for recognition of sudden cardiac arrest, and CPR technique and algorithm, where participants gave only approximately 30% correct answers. Nevertheless, we observed significant improvements in these domains after BLS training, which may confirm the importance of education. Individuals who had participated in first aid training in the past had better knowledge mainly about AED utilization (93% correct answers) in contrast to identifying sudden cardiac arrest (28% correct answers). Apart from the undeniable impact of BLS training on overall and specific knowledge about first aid in OHCA, it is also essential to point out its significance for bystanders’ attitude and awareness. Tanigawa et al. (2011) reported that after CPR training, bystanders were three times more likely to apply CPR for OHCA victims than those without CPR training. Conversely, we did not observe similar results in our study. The insufficient sample size might partially explain this outcome. Unfortunately, a single BLS training session is not enough to maintain dexterity. In a recent study, 70% of participants had received CPR training more than ten years ago, explaining the poor level of knowledge about resuscitation that was observed (Rajapakse et al. 2010). Improving and maintaining BLS knowledge at a satisfactory level might be achieved only with regular courses, which could be logistically difficult or even impossible. However, applications on smartphones and tablets and the use of virtual reality, broadcasts on TV, or BLS training in workplaces could be a solution (Atkins 2012; Cerezo Espinosa et al. 2019; Vancini et al. 2019). The social and medical benefit from high levels of knowledge of the BLS algorithm in the general population is inestimable; thus, widespread training should be considered. Our study has some limitations. The most important is its non-randomized design with all the potential for bias. Thus, there is a tendency for unmeasured confounders affecting the outcome. Furthermore, the small sample size limits the generalizability of results. Another potential drawback is that the study was conducted in a big academic city. We suspect that in rural areas, results might be worse. Despite these limitations, the presented data affect important issues and demonstrate that even a single BLS training session among cardiac patients improves their knowledge about first aid for OHCA.

Conclusion

BLS training improves knowledge about first aid for OHCA in cardiac patients. However, general knowledge about BLS prior to the course was poor, which underlines the importance of education and hands-on training to improve outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Atkins DL (2012) Bystander CPR: how to best increase the numbers. Resuscitation 83(9):1049–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.06.005

Atwood C, Eisenberg MS, Herlitz J, Rea TD (2005) Incidence of EMS-treated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation 67(1):75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.03.021

Berdowski J, Berg RA, Tijssen JGP, Koster RW (2010) Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation 81(11):1479–1487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.006

Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, Stolz U, Sanders AB, Kern KB, Vadeboncoeur TF, Clark LL, Gallagher JV, Stapczynski JS, LoVecchio F, Mullins TJ, Humble WO, Ewy GA (2010) Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 304(13):1447–1454. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1392

Bouland AJ, Halliday MH, Comer AC, Levy MJ, Seaman KG, Lawner BJ (2017) Evaluating barriers to bystander CPR among laypersons before and after compression-only CPR training. Prehosp Emerg Care 21(5):662–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1308605

Cerezo Espinosa C, Segura Melgarejo F, Melendreras Ruiz R, Garcia-Collado AJ, Nieto Caballero S, Juguera Rodriguez L, Pardo Rios S, Garcia Torrano S, Linares Stutz E, Pardo Rios M (2019) Virtual reality in cardiopulmonary resuscitation training: a randomized trial. Emergencias 31(1):43–46

Davies MJ, Thomas A (1984) Thrombosis and acute coronary-artery lesions in sudden cardiac ischemic death. N Engl J Med 310(18):1137–1140. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198405033101801

Engdahl J, Holmberg M, Karlson BW, Luepker R, Herlitz J (2002) The epidemiology of out-of-hospital “sudden” cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 52(3):235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9572(01)00464-6

Goniewicz M, Chemperek E, Mikuła A (2002) Attitude of students of high schools in Lublin towards the problem of first aid. Wiad Lek 1(55 Suppl):679–685

Han SK, Lee WS, Lee JE, Kim JS (2019) Prognostic value of the conversion to a Shockable rhythm in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients with initial non-Shockable rhythm. J Clin Med 8(5):644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050644

Hawkes C, Booth S, Ji C, Brace-McDonnell SJ, Whittington A, Mapstone J, Cooke MW, Deakin CD, Gale CP, Fothergill R, Nolan JP, Rees N, Soar J, Siriwardena AN, Brown TP, Perkins GD (2017) Epidemiology and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in England. Resuscitation 110:133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.10.030

Iwami T, Nichol G, Hiraide A, Hayashi Y, Nishiuchi T, Kajino K, Morita H, Yukioka H, Ikeuchi H, Sugimoto H, Nonogi H, Kawamura T (2009) Continuous improvements in “chain of survival” increased survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: a large-scale population-based study. Circulation 119(5):728–734. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.802058

Iwami T, Kitamura T, Kawamura T, Mitamura H, Nagao K, Takayama M, Seino Y, Tanaka H, Nonogi H, Yonemoto N, Kimura T (2012) Chest compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with public-access defibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation 126(24):2844–2851. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.109504

Krammel M, Schnaubelt S, Weidenauer D, Winnisch M, Steininger M, Eichelter J, Hamp T, van Tulder R, Sulzgruber P (2018) Gender and age-specific aspects of awareness and knowledge in basic life support. PLoS One 13(6):e0198918. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198918

Luc G, Baert V, Escutnaire J, Genin M, Vilhelm C, Di Pompéo C, CEL K, Segal N, Wiel E, Adnet F, Tazarourte K, Gueugniaud PY, Hubert H (2019) Epidemiology of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a French national incidence and mid-term survival rate study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 38(2):131–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2018.04.006

Lund-Kordahl I, Mathiassen M, Melau J, Olasveengen TM, Sunde K, Fredriksen K (2019) Relationship between level of CPR training, self-reported skills, and actual manikin test performance-an observational study. Int J Emerg Med 12(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-018-0220-9

Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska WA, Czyż-Szybenbejl K, Kwiecień-Jaguś K, Lewandowska K (2018) Prediction of cognitive dysfunction after resuscitation – a systematic review. Adv Interv Cardiol 14(3):225–232. https://doi.org/10.5114/aic.2018.78324

Mohamed E (2017) Effect of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training program on knowledge and practices of internship technical institute of nursing students. J Nurs Health Sci 06:73–81. https://doi.org/10.9790/1959-0603037381

Nurnberger A, Sterz F, Malzer R, Warenits A, Girsa M, Stockl M, Hlavin G, Magnet IAM, Weiser C, Zajicek A, Gluck H, Grave MS, Muller V, Benold N, Hubner P, Kaff A (2013) Out of hospital cardiac arrest in Vienna: incidence and outcome. Resuscitation 84(1):42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.07.002

Özbilgin Ş, Akan M, Hancı V, Aygün C, Kuvaki B (2015) Evaluation of public awareness, knowledge and attitudes about cardiopulmonary resuscitation: report of İzmir. Turkish J Anaesthesiol Reanim 43(6):396–405. https://doi.org/10.5152/TJAR.2015.61587

Pehlivan M, Mercan NC, Çinar İ, Elmali F, Soyöz M (2019) The evaluation of laypersons awareness of basic life support at the university in Izmir. Turk J Emerg Med 19(1):26–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjem.2018.11.002

Perkins GD, Olasveengen TM, Maconochie I, Soar J, Wyllie J, Greif R, Lockey A, Semeraro F, Van de Voorde P, Lott C, Monsieurs KG, Nolan JP (2018) European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation: 2017 update. Resuscitation 123:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.12.007

Rajapakse R, Noc M, Kersnik J (2010) Public knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Republic of Slovenia. Wien Klin Wochenschr 122(23–24):667–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-010-1489-8

Rasmus A, Czekajlo MS (2000) A national survey of the polish population’s cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge. Eur J Emerg Med 7(1):39–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/00063110-200003000-00008

Tanigawa K, Iwami T, Nishiyama C, Nonogi H, Kawamura T (2011) Are trained individuals more likely to perform bystander CPR? An observational study. Resuscitation 82(5):523–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.01.027

Valenzuela TD, Roe DJ, Nichol G, Clark LL, Spaite DW, Hardman RG (2000) Outcomes of rapid defibrillation by security officers after cardiac arrest in casinos. N Engl J Med 343(17):1206–1209. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200010263431701

Vancini LR, Nikolaidis TP, de Lira AC, Vancini-Campanharo RC, Viana BR, Andrade DM, Rosemann T, Knechtle B (2019) Prevention of sudden death related to sport: the science of basic life support—from theory to practice. J Clin Med 8(4):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8040556

Villalobos F, Del Pozo A, Rey-Reñones C, Granado-Font E, Sabaté-Lissner D, Poblet-Calaf C, Basora J, Castro A, Flores-Mateo G (2019) Lay people training in CPR and in the use of an automated external defibrillator, and its social impact: a community health study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(16):2870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162870

Wingen S, Schroeder DC, Ecker H, Steinhauser S, Altin S, Stock S, Lechleuthner A, Hohn A, Bottiger BW (2018) Self-confidence and level of knowledge after cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in 14 to 18-year-old schoolchildren: a randomised-interventional controlled study in secondary schools in Germany. Eur J Anaesthesiol 35(7):519–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000000766

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Bartosz Partyński and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Jagiellonian University.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 32 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Partyński, B., Tokarek, T., Dziewierz, A. et al. Impact of basic life support training on knowledge of cardiac patients about first aid for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 21–26 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01442-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01442-5