Abstract

Aim

Asian Americans have high levels of undiagnosed diabetes, but little is known about what influences diabetes screening in this group. We determined which sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors were associated with diabetes screening in the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) recommended screening groups for Asian Americans.

Subjects and methods

We included Asian Americans from the 2015 and 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System who fit the ADA’s diabetes screening guidelines and responded to a diabetes screening question. Logistic regression models were created to examine associations between sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors and diabetes screening in Asian Americans.

Results

Being a college graduate and having high blood pressure were associated with higher levels of diabetes screening for the two screening groups. A trend of decreased diabetes screening with less educational attainment was observed in both screening groups.

Conclusion

Diabetes screening in Asian Americans is influenced by socioeconomic and clinical factors. Additional work is needed to identify other Asian American-specific cultural factors that may have an impact on the decision to seek diabetes screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A disproportionate 1 in 2 Asian Americans are living with undiagnosed type II diabetes compared to 1 in 4 people from the general population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC 2016c). According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), diabetes screening is recommended for all asymptomatic adults < 45 years old who are overweight (25 kg/m2 ≤ body mass index (BMI) ≤ 29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) with one or more diabetes risk factors (African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander ethnicity; hypertension; hypercholesteremia, etc.), as well as all adults ≥ 45 years old regardless of BMI (ADA 2019; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2019; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIDDK 2018; US Preventive Services Task Force 2015). However, diabetes often goes undetected in Asian Americans because it can develop at a younger age and a lower BMI than typically observed (Becerra and Becerra 2015; CDC 2016c). In addition, the excess weight that is often characteristic of diabetes onset is typically absent in Asian Americans with undiagnosed diabetes (CDC 2016c). As young Asian Americans of normal weight have a higher propensity to have undiagnosed diabetes than similar individuals from other racial/ethnic groups, the ADA recommends that all Asian American adults > 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 undergo diabetes screening (ADA 2014; Araneta et al. 2015).

Despite increasing recognition of the need for routine diabetes screening in Asian Americans, little is known about the factors that influence diabetes screening in this group (Hsu et al. 2015; Tung et al. 2017). Existing work on diabetes screening in Asian Americans has mainly focused on the disparities in screening between this group compared to other racial/ethnic groups (Tung et al. 2017). As a result, there is a need for a contemporary US study that considers the influence that sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors have on diabetes screening in Asian Americans.

In this study, we examined the influence of sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors on diabetes screening in the ADA recommended screening groups for Asian Americans (ADA 2014). Through the use of regression models, we simultaneously determined the independent role of these factors on diabetes screening while adjusting for them. This study’s results allowed for the identification of sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics that influence diabetes screening in Asian American recommended screening groups and whether these factors differ between the two screening groups.

Methods

Study sample

We utilized two of the CDC’s nationally representative Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys, 2015 and 2017, for our study (CDC 2012, 2014a, b, 2016ab, 2018b). The BRFSS survey is administered via landline or cell phone and collects information on the health behaviors and chronic conditions of residents in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (CDC 2012, 2014a, b, 2016a, b, 2018b). Commercially available phone lists from Genesys, Inc. are used to contact potential BRFSS survey participants (Judd et al. 2013). The BRFSS performs oversampling and raking adjustments to ensure representativeness of some minority groups which are less likely to have access to telephones and cell phones (CDC 2018a; Judd et al. 2013).

We combined the 2015 and 2017 BRFSS to maximize the study’s sample and increase the power of our analyses. BRFSS surveys from 2014 and earlier were not included since the ADA recommendations for diabetes screening in Asian Americans were not released until December 23rd, 2014 (ADA 2014). The 2016 BRFSS survey was not included since it did not contain information on blood pressure, an important clinical factor of diabetes (CDC 2017a). The BRFSS datasets are publicly available for download at the CDC’s website (https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_data.htm) (CDC 2014b).

The study was comprised of Asian Americans who fell within the ADA’s guidelines for diabetes screening in Asian Americans (ADA 2014). This consisted of two groups: (1) Asian Americans < 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 and (2) Asian Americans ≥ 45 years old (Tung et al. 2017). For Asian Americans < 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2, we considered Asian American ethnicity as the additional diabetes risk factor (ADA 2014). Eligible study participants also needed to respond either “Yes” or “No” to “Have you had a test for high blood sugar or diabetes within the past three years?” (Section 1.1 in the 2015 and 2017 BRFSS) (CDC 2016a, 2018b). People whose answer was either “Don’t know/Not Sure”, “Refused”, or “Missing” to the question were excluded from the study (CDC 2016a).

Covariates

Information on sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors were also obtained from the 2015 and 2017 BRFSS surveys (CDC 2016a, 2018b). All these factors were categorical and included age, sex, household income, education, healthcare coverage, access to a personal doctor, BMI, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels (CDC 2016a, 2018b). For BMI, we have chosen to use the World Health Organization’s (WHO) cutoff points for underweight (BMI < 18.50 kg/m2), normal weight (18.50 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 23.00 kg/m2), overweight (23.00 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 27.50 kg/m2), and obesity (BMI ≥ 27.50 kg/m2) in Asian Americans instead of the BMI cutoff points typically used for the general population (Stegenga et al. 2014). These particular factors were chosen because they have been shown to be associated with diabetes in the literature or are associated with screening (Fletcher et al. 2002; NIDDK 2016; Oberoi et al. 2016). Not only does including these factors in the analysis allow us to examine their influence on diabetes screening in Asian Americans, but it also allows us to adjust for them and control, to a large extent, any confounding that could bias the study results (McNamee 2005).

Statistical models

We conducted bivariate analyses using Chi-squared tests to determine if there were any differences between Asian Americans that had diabetes screening in the past three years and those that did not. Separate logistic regression models were created for each of the two recommended diabetes screening groups for Asian Americans (ADA 2014). The logistic model for Asian Americans < 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 included sex, household income, education, healthcare coverage, access to a personal doctor, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels as covariates, while the logistic model for Asian Americans ≥ 45 years old included sex, household income, education, healthcare coverage, access to a personal doctor, BMI, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. Neither model adjusted for age since the two ADA recommended testing groups for Asian Americans essentially restricted study participants by age (Jager et al. 2008; Pourhoseingholi et al. 2012). In addition, we did not include BMI in the logistic model for Asian Americans < 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 since people in this group were restricted by the BMI cutoff (Jager et al. 2008; Pourhoseingholi et al. 2012). Survey weights were used in the logistic models to account for the complex survey design and unequal weighting of BRFSS data (CDC 2018a). For covariates that had ≥ 10% of their values missing, we created an indicator variable for the “missing” category and included this indicator variable in the two logistic models. All analyses were conducted in Stata 15 (StataCorp 2017).

Results

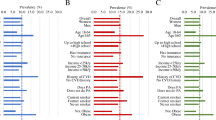

Our study was comprised of 6734 Asian American BRFSS respondents who fell into one of the two risk groups recommended for screening by the ADA (Table 1). Of the ,734 individuals in the study, 3313 had received diabetes screening in the past three years (49.2%), while 3421 had not (50.8%). Study participants were divided roughly evenly by age and gender, primarily made $50,000 or more a year (45.4%), and were mostly college-educated (56.9%). In terms of access to medical care, nearly all of the respondents had healthcare coverage (89.5%) and a majority had one healthcare provider (65.6%). Combined, overweight and obese respondents made up almost 60% of the study sample, and although the majority of respondents reported having high blood pressure (77.0%), over half of respondents noted that they did not have high cholesterol (62.3%).

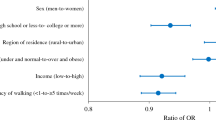

In Table 2, we report odds ratios (ORs) for the two risk groups, Asian Americans who are < 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 and Asian Americans ≥ 45 years old. A combined 3041 Asian Americans were < 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 in the 2015 and 2017 BRFSS surveys. In this young and overweight/obese Asian American risk group, college graduates had higher odds of diabetes screening compared to high school graduates (OR: 1.63), those with healthcare coverage were more likely to have had diabetes screening compared to those without healthcare coverage (OR: 1.63), those with one healthcare provider had higher odds of diabetes screening compared to those with no provider (OR: 1.72), and those who reported having high blood pressure had higher odds of diabetes screening compared to those without high blood pressure (OR: 2.06). Except for healthcare coverage, all of these associations were statistically significant, with p-values < 0.05. We also observed a pattern of decreased diabetes screening with lower levels of education among Asian Americans < 45 years old with a BMI > 23 kg/m2 in the study.

The second ADA recommended screening group, Asian Americans ≥ 45 years old, contained 3290 individuals. In contrast to the first ADA recommended screening group for Asian Americans, all other income levels had higher odds of diabetes screening compared to those earning < $15,000, college graduates (OR: 2.13), those with some college or technical school education (OR: 1.79) had higher odds of diabetes screening compared to high school graduates, and those with high blood pressure had higher odds of diabetes screening compared to those without high blood pressure (OR: 2.18). All of these associations were significant, with p-values < 0.05. BMI, which was included as a covariate in modeling this group, was not found to be significantly associated with diabetes screening. In Asian Americans ≥ 45 years old, lower education attainment corresponded with decreased diabetes screening.

Discussion

Using national BRFSS data from 2015 and 2017, we examined which sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors were associated with diabetes screening in the ADA recommended screening groups for Asian Americans. Although the relationships between certain factors and diabetes screening differed for the two screening groups, being a college graduate and having high blood pressure was associated with higher levels of diabetes screening for both Asian Americans < 45 years old with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 and Asian Americans ≥ 45 years old. We also found a trend of decreased diabetes screening with decreasing education for both Asian American screening groups.

Previous work on diabetes screening in Asian Americans has primarily concentrated on noting the low levels of diabetes screening in this group compared to other racial groups, rather than which factors influence diabetes screening in Asian Americans (Tung et al. 2017). In a study looking at diabetes screening among Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians/Alaska Natives that were either < 45 years old with BMI ≥ 25kg/m2 or ≥ 45 years old using BRFSS data, researchers found that not only were Asians the least likely to undergo diabetes screening of all races, but that they had a 34% lower odds of diabetes screening compared to Whites (Tung et al. 2017). Our study highlights factors such as education and hypertension that may shape these diabetes screening disparities among Asian Americans. Studies have shown that those with less educational attainment have limited health literacy, decreased desire to seek out preventative medical care, and unhealthier lifestyle behaviors (Faught et al. 2017; Jansen et al. 2018; Lachman and Weaver 1998; van der Heide et al. 2013; Zimmerman et al. 2015). Both Asian Americans without hypertension fitting the ADA recommended guidelines for diabetes screening and their physicians may not feel that these patients are at increased risk for diabetes and, thus, may not request diabetes screening (Hsu et al. 2015). It is of note that Asian Americas have low screening for other diseases, such as breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer, even after adjusting for sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors compared to other racial/ethnic groups (Pourhoseingholi et al. 2012; Tung et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2008). These findings may reflect the need to consider Asian American cultural beliefs and attitudes towards medical care in future studies on diabetes screening in this group (Jin et al. 2002; Juckett 2005; Kim and Zane 2016; Kim and Keefe 2010; Tung et al. 2017).

This study has several limitations that need to be considered. As the BRFSS is a self-reported survey, some misclassification of survey measures may occur and it is difficult to assess the true accuracy of the entire self-reported BRFSS dataset (CDC 2012, 2014b, 2016b). However, there have been studies to evaluate the accuracy of BRFSS datasets. For instance, a study comparing Massachusetts electronic health records (EHR) to Massachusetts BRFSS responses found that the prevalence of obesity (EHR: 22.8%, BRFSS: 23.8%), along with other medical conditions like hypertension and diabetes, were very similar between the two data sources (Klompas et al. 2017). In addition, a BRFSS validation study that examined the correlation between self-reported BMI with in-clinic BMI measurements found a correlation of R2 = 0.89 for men and a correlation of R2 = 0.92 for women (Andresen et al. 2003). In that context, we believe that any issues surrounding the accuracy of self-report would be minor if not negligible. Minor loss of accuracy due to self-report will likely result in minimal, if any, non-differential misclassification bias (Schneider et al. 2012). Although we adjusted for multiple sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors, some residual and unmeasured confounding may remain (Fewell et al. 2007). However, we adjusted for many of the covariates included in other studies on diabetes and diabetes screening in our analyses (Agardh et al. 2011; Arnetz et al. 2014; Casagrande and Cowie 2012; CDC 2017b; Cheung and Li 2012; Conway et al. 2018; Ganz et al. 2014; Harris and Eastman 2000; Kautzky-Willer et al. 2016; Narayan et al. 2007; Raparelli et al. 2017; Steele et al. 2017; Tung et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2012).

The limitations of our study are countered by several of its strengths. This is the first study on diabetes screening in Asian Americans to use the 2014 ADA recommended screening guidelines for this racial/ethnic group. Although using the BRFSS causes reliance on self-reported data, it allowed our study to have a national sample size > 6000 respondents that accurately represents the distribution of Asian Americans in the USA. Additionally, we used 2017 BRFSS data, the most recent survey with information on US diabetes screening. Relative to other studies on US diabetes screening in Asian Americans, this study was based off of more contemporary data (Tung et al. 2017). Given that this study’s data were as contemporary as possible, our findings accurately portray the current landscape of diabetes screening in Asian Americans.

Conclusions

Our study sought to determine which sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors were associated with diabetes screening in the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) recommended screening groups for Asian Americans and whether these associations differed between the two groups. The study’s results indicated that, despite differences in which factors influenced diabetes screening in the two groups, there was a pattern of decreased diabetes screening with lower education and those without hypertension. We shed some light on what factors impact diabetes screening in Asian Americans and highlight the importance of considering cultural factors in future efforts to increase diabetes screening in this racial group. The study’s findings demonstrate that further work is warranted to determine additional factors that play a role in diabetes screening in Asian Americans in order to develop culturally sensitive initiatives that will increase the number of undiagnosed diabetes cases that can be detected early and, ultimately, reduce future diabetes morbidity and mortality in this group.

References

Agardh EE, Sidorchuk A, Hallqvist J et al (2011) Burden of type 2 diabetes attributed to lower educational levels in Sweden. Popul Health Metr 9:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-9-60

American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2014) American Diabetes Association Releases Position Statement on New BMI Screening Cut Points for Diabetes in Asian Americans

American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2019) Complications. https://www.diabetes.org/diabetes/complications.

Andresen EM, Catlin TK, Wyrwich KW, Jackson-Thompson J (2003) Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health 57:339–343. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.5.339

Araneta MR, Kanaya AM, Hsu WC et al (2015) Optimum BMI cut points to screen Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 38:814–820. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-2071

Arnetz L, Ekberg NR, Alvarsson M (2014) Sex differences in type 2 diabetes: focus on disease course and outcomes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 7:409–420. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S51301

Becerra MB, Becerra BJ (2015) Disparities in age at diabetes diagnosis among Asian Americans: implications for early preventive measures. Prev Chronic Dis 12:E146. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150006

Casagrande SS, Cowie CC (2012) Health insurance coverage among people with and without diabetes in the U.S. adult population. Diabetes Care 35:2243–2249. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0257

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2012) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey data. CDC, Atlanta

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014a) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. 2013 codebook report. Land-line and cell-phone data

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014b) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Survey data. CDC, Atlanta

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016a) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. 2015 codebook report. Land-line and cell-phone data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2015/pdf/codebook15_llcp.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016b) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Survey data. CDC, Atlanta, GA

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016c) Diabetes and Asian Americans. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/spotlights/diabetes-asian-americans.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2017a) LLCP 2016 codebook report. Overall version data weighted with _LLCPWT. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/codebook16_llcp.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2017b) National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. http://www.diabetes.org/assets/pdfs/basics/cdc-statistics-report-2017.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2018a) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Comparability of data BRFSS 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2017/pdf/compare-2017-508.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2018b) LLCP 2017 codebook report. Overall version data weighted with _LLCPWT. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2017/pdf/codebook17_llcp-v2-508.pdf

Cheung BMY, Li C (2012) Diabetes and hypertension: is there a common metabolic pathway? Curr Atheroscler Rep 14:160–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-012-0227-2

Conway BN, Han X, Munro HM et al (2018) The obesity epidemic and rising diabetes incidence in a low-income racially diverse southern US cohort. PLoS One 13:e0190993

Faught EL, Gleddie D, Storey KE, Davison CM, Veugelers PJ (2017) Healthy lifestyle behaviours are positively and independently associated with academic achievement: An analysis of self-reported data from a nationally representative sample of Canadian early adolescents. PLoS One 12:e0181938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181938

Fewell Z, Davey Smith G, Sterne JAC (2007) The impact of residual and unmeasured confounding in epidemiologic studies: a simulation study. Am J Epidemiol 166:646–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm165

Fletcher B, Gulanick M, Lamendola C (2002) Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cardiovasc Nurs 16:17–23

Ganz ML, Wintfeld N, Li Q, Alas V, Langer J, Hammer M (2014) The association of body mass index with the risk of type 2 diabetes: a case–control study nested in an electronic health records system in the United States. Diabetol Metab Syndr 6:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-5996-6-50

Harris MI, Eastman RC (2000) Early detection of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus: a US perspective. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 16:230–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DMRR122>3.0.CO;2-W

Hsu WC, Araneta MRG, Kanaya AM, Chiang JL, Fujimoto W (2015) BMI cut points to identify at-risk Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes screening. Diabetes Care 38:150–158. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-2391

Jager KJ, Zoccali C, MacLeod A, Dekker FW (2008) Confounding: what it is and how to deal with it. Kidney Int 73:256–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ki.5002650

Jansen T, Rademakers J, Waverijn G, Verheij R, Osborne R, Heijmans M (2018) The role of health literacy in explaining the association between educational attainment and the use of out-of-hours primary care services in chronically ill people: a survey study. BMC Health Serv Res 18:394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3197-4

Jin XW, Slomka J, Blixen C (2002) Cultural and clinical issues in the care of Asian patients. Cleve Clin J Med 69:50. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.69.1.50

Juckett G (2005) Cross-cultural medicine. Am Fam Physician 72:2267–2274

Judd SE, Gutiérrez OM, Newby PK et al (2013) Dietary patterns are associated with incident stroke and contribute to excess risk of stroke in black Americans. Stroke 44:3305–3311. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.113.002636

Kautzky-Willer A, Harreiter J, Pacini G (2016) Sex and gender differences in risk, pathophysiology and complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev 37:278–316. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2015-1137

Kim W, Keefe RH (2010) Barriers to healthcare among Asian Americans. Soc Work Public Health 25:286–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371910903240704

Kim JE, Zane N (2016) Help-seeking intentions among Asian American and White American students in psychological distress: Application of the health belief model. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 22:311–321

Klompas M, Cocoros NM, Menchaca JT et al (2017) State and local chronic disease surveillance using electronic health record systems. Am J Public Health 107:1406–1412. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2017.303874

Lachman ME, Weaver SL (1998) The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 74:763–773

McNamee R (2005) Regression modelling and other methods to control confounding. Occup Environ Med 62:500–506

Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Williamson DF (2007) Effect of BMI on lifetime risk for diabetes in the U.S. Diabetes Care 30:1562–1566. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-2544

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2019) Overweight and obesity. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/overweight-and-obesity

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (2016) Risk factors for type 2 diabetes. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/risk-factors-type-2-diabetes

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (2018) Prediabetes screening: how and why. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/communication-programs/ndep/health-professionals/game-plan-preventing-type-2-diabetes/prediabetes-screening-how-why

Oberoi S, Chaudhary N, Patnaik S, Singh A (2016) Understanding health seeking behavior. J Family Med Prim Care 5:463–464. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.192376

Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani AR, Vahedi M (2012) How to control confounding effects by statistical analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 5:79–83

Raparelli V, Morano S, Franconi F, Lenzi A, Basili S (2017) Sex differences in type-2 diabetes: implications for cardiovascular risk management. Curr Pharm Des 23:1471–1476. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612823666170130153704

Schneider KL, Clark MA, Rakowski W, Lapane KL (2012) Evaluating the impact of non-response bias in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). J Epidemiol Community Health 66:290–295. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.103861

StataCorp (2017) Stata statistical software: release 15. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX

Steele CJ, Schöttker B, Marshall AH et al (2017) Education achievement and type 2 diabetes—what mediates the relationship in older adults? Data from the ESTHER study: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 7:e013569. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013569

Stegenga H, Haines A, Jones K, Wilding J; Guideline Development Group (2014) Identification, assessment, and management of overweight and obesity: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 349:g6608

Tung EL, Baig AA, Huang ES, Laiteerapong N, Chua K-P (2017) Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes screening between Asian Americans and other adults: BRFSS 2012–2014. J Gen Intern Med 32:423–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3913-x

US Preventive Services Task Force (2015) Final recommendation statement. Abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening

van der Heide I, Wang J, Droomers M, Spreeuwenberg P, Rademakers J, Uiters E (2013) The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J Health Commun 18(Suppl 1):172–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.825668

Wang JH, Sheppard VB, Schwartz MD, Liang W, Mandelblatt JS (2008) Disparities in cervical cancer screening between Asian American and Non-Hispanic white women Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:1968–1973. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-08-0078

Zhang X, Bullard KM, Gregg EW et al (2012) Access to health care and control of ABCs of diabetes. Diabetes Care 35:1566–1571. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0081

Zimmerman EB, Woolf SH, Haley A (2015) Understanding the relationship between education and health: a review of the evidence and an examination of community perspectives. In: Kaplan RM, Spittel ML, David DH (eds) Population health: behavioral and social science insights. AHRQ publication no. 15-0002, pp 347–384

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgements. This work was not funded by any financial grants or other sources of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PT originated the idea and the study design. LaT ran the data analyses and interpreted the results. LiT assisted with the study design. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The BRFSS data used in this study is a secondary publicly available data source that has been completely anonymized and released for public use by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Informed consent

This article is exempt from needing informed consent as no human participants were involved in the study and the data used have been completely anonymized and approved for public use by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Disclosure

PT does not have any financial support or relationship that may pose a conflict of interest. LaT does not have any financial support or relationship that may pose a conflict of interest. LiT does not have any financial support or relationship that may pose a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, P., Tran, L. & Tran, L. Sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors associated with diabetes screening in Asian Americans. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 1455–1462 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01267-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01267-2