Abstract

Aims

We examine whether primary care continuity of care (PCCOC) improved for Medicare beneficiaries under a 3-year demonstration to help federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) become patient-centered medical homes (PCMH).

Subjects and methods

We used a difference-in-differences analysis to compare changes over time in PCCOC for beneficiaries in 503 demonstration sites to those in 827 comparison sites. We measured PCCOC using the claims-based usual provider of care (UPC) index (range 0–1) indicating the proportion of visits to the most commonly seen provider or practice over a 1-year period.

Results

Average baseline UPC index values were 0.77 at the provider level and 0.88 at the practice level, with similar values for demonstration and comparison sites. UPC decreased more over time in demonstration clinics than comparison clinics, but the magnitude of these changes were small.

Conclusions

FQHCs already have high levels of PCCOC. These levels did not increase in association with the 3-year PCMH demonstration. Continuity for practices is higher than for providers, suggesting that Medicare beneficiaries may see multiple providers within one FQHC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) have incorporated elements of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model since their inception. FQHCs provide care to low-income and high-need populations in underserved areas (HRSA 2016). FQHCs have historically provided high-quality, team-based, coordinated primary care to patients regardless of their ability to pay. They must provide fees on a sliding scale according to a patient’s income, and they receive enhanced reimbursements and additional grant funding to support their operations (Quyen et al. 2011; Shi et al. 2015; Starfield et al. 2005).

FQHCs are increasingly serving both disabled and elderly Medicare beneficiaries. The number of Medicare beneficiaries served in FQHCs nearly doubled from 1 to 2 million beneficiaries between 2005 and 2014, according to the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC 2016). While Medicare does not limit provider selection for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries may prioritize care at FQHCs because they are often convenient, provide interpreters or transportation services, and offer culturally-sensitive care (HRSA 2017b).

Given the growth of FQHCs as a usual source of care for Medicare beneficiaries living in underserved areas (Chang et al. 2016), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) recent FQHC Advanced Primary Care Practice (APCP) Demonstration evaluated whether helping FQHCs to achieve PCMH recognition improved outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries (Kahn et al. 2015a; Kahn et al. 2015b). Advanced primary care practices build upon the joint principles of a strong primary care delivery system including improved access, coordinated and comprehensive care, and continuous quality improvement. Several organizations, including the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), have encouraged practices to codify their application of PCMH principles (American Academy of Family Physicians et al. 2007; Mahmud et al. 2018). With CMS’s APCP Demonstration, FQHCs participating in the Demonstration received financial support and technical assistance to achieve NCQA Level 3 (the highest NCQA level of recognition) within a 3-year period. Recognition depended on scoring according to six standards, each of which comprised multiple elements. Recognized sites achieved Level 1, 2, or 3 recognition based on their total number of points scored across elements and on the number of points scored on must-pass elements. Points were assigned for the following six standards: (1) Enhance Access and Continuity, (2) Identify and Manage Patient Population, (3) Plan and Manage Care, (4) Provide Self-Care Support and Community Resources, (5) Track and Coordinate Care, and (6) Measure and Improve Performance (NCQA 2016).

An important dimension of care quality as reflected in the PCMH standards is care coordination, where information is shared among providers, providers communicate with patients, and follow-up care is appropriate (NQF 2010; PCPCC 2011). Continuity of care (COC), which refers to an ongoing relationship between a patient and his or her provider or practice and is one of the key elements of advanced primary care models, has been associated with improved outcomes and reduced costs (Amjad et al. 2016; DuGoff et al. 2016; Hussey et al. 2014; Maarsingh et al. 2016). COC among primary care providers might be particularly important for FQHCs, since the vast majority of the services FQHCs provide are primary-care focused. One of the mechanisms through which we hypothesize that the demonstration would improve beneficiary health and lower spending is through improved COC.

The FQHC Demonstration provided an opportunity to assess whether primary care COC (PCCOC) for Medicare beneficiaries visiting FQHCs changed with the Demonstration. Several studies have evaluated the influence of primary care delivery on outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries in FQHCs compared with other primary care settings, but PCCOC has often not been included as an outcome in these studies (Bailey and Goodman-Bacon 2015; Jackson et al. 2013; Mukamel et al. 2016; Shi et al. 2017; Wright et al. 2015).

This analysis includes three main objectives. First, we characterize baseline levels of PCCOC, measured both at the provider and the practice level, among Medicare beneficiaries seeking care within a nationwide sample of FQHCs. Second, we examine whether differences emerged over time in PCCOC for Medicare beneficiaries attributed to demonstration versus comparison FQHCs. Finally, we explore whether PCCOC was influenced by the CMS Demonstration for pre-specified subgroups of Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods

Detailed descriptions of the intervention and evaluation methods are available in prior reports and articles (Kahn et al. 2017; Kahn et al. 2015b; Timbie et al. 2017).

Intervention

The CMS FQHC APCP Demonstration assisted participating FQHCs in becoming NCQA-recognized Level-3 PCMHs using NCQA’s 2011 specifications (NCQA 2016). Level 3 recognition requires documentation of enhanced access and better data systems to manage and track populations. Support provided to demonstration sites included care management fees ($18 per quarter per attributed Medicare beneficiary), transformation assistance in the form of webinars and one-on-one coaching, and periodic feedback reports on beneficiary outcomes and spending, as well as clinic-level performance summaries.

Study sample

The demonstration sample included 503 FQHC practice sites that CMS selected to ensure diversity with respect to region, urbanicity, electronic health record adoption, baseline scores on the NCQA PCMH instrument, and receipt of medical home-related payments from payers. The evaluation team selected 827 comparison sites that were selected based on comparability of patient, site, and geographic characteristics. There was no overlap in sites from the same organization in the treatment and control groups, although within each group, an organization could have multiple sites.

Beneficiaries eligible for inclusion in the evaluation sample had to be continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B during the baseline year (November 2010 to October 2011). Beneficiaries were ineligible if they were enrolled in Medicare Advantage or had end-stage renal disease at any point during that period. Since the outcome measure for PCCOC can lead to spurious effects for patients with few visits (Eriksson and Mattsson 1983; Liss et al. 2011; Perry et al. 2016), we also required that the sample for this study have at least three primary care visits to an ambulatory provider in the baseline year and in each of the 3 demonstration years. The 123,653 beneficiaries in the final sample were attributed to a primary care practice responsible for the plurality of their primary care visits in the baseline year (the most common provider). If there was a tie between two providers, the beneficiary was assigned to the practice associated with the most recent claim. More details on the procedures noted here can be found in the appendix to Timbie et al. (2017).

Data

We used Medicare Parts A and B fee-for-service claims from November 2010 to October 2014 for beneficiaries attributed to demonstration and comparison FQHCs.

Outcome: measuring PCCOC

We measured PCCOC using the claims-based usual provider of care (UPC) index, which represents the proportion of primary care visits within a year to the provider responsible for the plurality of services over the same year. We chose to use the UPC index instead of the Bice–Boxerman index as our measure of continuity because the units of measurement provide a more straightforward interpretation of the concentration of visits with the most common provider. While both are measured on a 0 to 1 scale, the Bice–Boxerman is interpreted as the degree of care dispersion across all of a patient’s providers (Bice and Boxerman 1977; Pollack et al. 2016), while the UPC can be interpreted as the proportion of visits to the most common provider. Other studies have previously demonstrated that the UPC index is correlated with the Bice–Boxerman COC index (Pollack et al. 2016; Romaire et al. 2014; Smedby et al. 1984; Smedby et al. 1986).

Our initial examination of the UPC index indicated that approximately 30% of beneficiary-year measurements had a provider-level UPC value of 1, meaning that almost one-third of beneficiaries visited the same provider every year. In contrast, approximately 60% of the beneficiary-year measurements had a practice-level UPC value of 1, meaning that about three in five beneficiaries visited the same practice for an entire year, but not necessarily the same provider within the practice. To monitor changes in the proportion of beneficiaries who consistently see the same primary care provider in a given year, we also analyzed a binary measure of perfect COC (equal to a value of 1 if the beneficiary had a UPC value of 1 in the given year, and zero otherwise) over time, in addition to the continuous measure that is calculated on a 0 to 1 scale.

Analysis of provider- vs practice-level continuity

Practice-level continuity assesses the proportion of each patient’s primary care visits to the practice site with the plurality of services over the year, while provider-level continuity assesses the proportion of a patient’s primary care visits to a particular provider within the practice. Patients who consistently obtain care from the same practice may have better outcomes than patients who seek care from multiple, unaffiliated practices (Perry 2016).

For the practice-level COC analyses, a primary care practice was defined as an FQHC site, rural health clinic (RHC), or a non-FQHC/non-RHC primary care practice. We used provider transaction access numbers (PTANs) to identify unique FQHCs and RHCs, and tax identification numbers (TINs) for other primary care practices. For the provider-level analyses, a primary care provider was defined as a provider with one of the following taxonomy codes associated with their National Provider Identifier (NPI): internal medicine, general practice, family medicine, OB/GYN, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or geriatrics.

Analysis of changes over time among demonstration and comparison FQHCs

We used a difference-in-differences study design to compare changes in the UPC index over time for beneficiaries attributed to the demonstration versus comparison sites. We analyzed changes in UPC indices across each of the 3 demonstration years (November 2011 to October 2014) compared with the baseline year (November 2010 to October 2011) between the demonstration and control groups. This study design allowed us to control for unobserved factors that may differ between the two groups and that may influence COC, so long as these factors do not vary over time.

To strengthen the internal validity of the analysis, we applied propensity score weights to each beneficiary’s data that reflected his or her propensity to be attributed to a demonstration site. These weights are a function of baseline beneficiary, site, and geographic characteristics, including 14 baseline claims-based quality and utilization measures as well as the baseline PCCOC. For all analyses, we used propensity-score weighted generalized estimating equation (GEE) models to assess the relationship between the demonstration and the UPC index, while controlling for beneficiary- and site-level characteristics that may influence COC independent of the demonstration. Each model used the appropriate family and link function to account for the varied distributions of each outcome. These characteristics and their description are summarized in Table 1. The standard errors account for the clustering of beneficiaries within sites and over time.

Sensitivity analyses examining beneficiary and FQHC subgroups

To explore potential heterogeneity in the effect of the demonstration on PCCOC, we examined effects within beneficiary or FQHC subgroups where we hypothesized that demonstration effects on PCCOC might be strongest. The subgroups are as follows: 1) age 85+ versus 65–84 years; 2) black versus white race; 3) disabled versus non-disabled; 4) eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, (i.e., “dual eligibility”) versus non-dual; 5) rural versus urban site location; and, 6) medium-sized FQHCs with 5–14 sites versus smaller FQHCs with less than 5 sites. We ran separate models for each subgroup using a three way interaction term between the subgroup, the intervention indicator and the post-period in our difference-in-differences model.

Full models and description of control variables can be found in Appendix Table 5. Appendix Table 6 presents the results of all sensitivity analyses. All analyses were conducted in SAS, Version 9.3. The RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee approved this study.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Just over half the sample was dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and a similar percentage of beneficiaries were disabled. Over 60% of beneficiaries in both the demonstration and comparison groups lived in urban areas, and the majority of beneficiaries were attributed to sites that were part of multi-site FQHCs. Beneficiaries in both groups had just over seven provider visits per year, on average. Table 1 summarizes other characteristics of the beneficiary sample before applying propensity score weights.

Baseline primary care COC

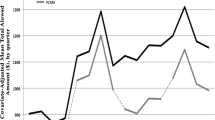

PCCOC was high among both providers and practices in the baseline (Fig. 1) year before the demonstration began. Figure 1 displays the unadjusted trends in the UPC index at the provider level and practice level over the analysis period. At baseline, the respective demonstration and comparison provider level PCCOC UPC index values were 0.77 and 0.78, and the practice-level PCCOC UPC index values were 0.88 and 0.89. Thirty-eight percent of beneficiaries had perfect provider-level continuity in the demonstration sites, and 37% in the comparison sites at baseline. Sixty-two percent of beneficiaries had perfect practice-level continuity at baseline for both demonstration and comparison groups.

Unadjusted trends in PCCOC over time, provider and practice level, demonstration group vs comparison. Notes: upper lines, continuous measure, lower lines, binary measure. PCCOC = primary care continuity of care is measured with the usual provider of care index (UPC). The continuous UPC index represents the proportion of visits to the provider that is responsible for the plurality of primary care services provided to each beneficiary. The binary UPC measure represents the proportion of beneficiaries with perfect provider-level primary care continuity (achieving a UPC index equal to 1). The ‘demonstration’ clinics are those participating in the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Federally Qualified Health Center Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration. The difference between the baseline and year 3 level for both the continuous and binary measures and the practice and provider levels are all significant at the p = 0.05 level.

Unadjusted changes in primary care COC with time

The trends in unadjusted PCCOC in both the demonstration and comparison groups declined slightly across all years from baseline to year 3 for both the provider and practice levels (Fig. 1), and the magnitude of the declines were similar between demonstration and comparison sites. The provider UPC index values decreased slightly from 0.77 to 0.75 in the demonstration sites and from 0.77 to 0.74 in the comparison sites. The practice-level UPC index values declined by a similar degree, as did the binary measure (Fig. 1).

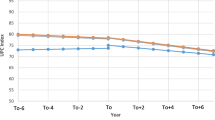

Difference-in-differences regression results

The effect of the demonstration on the continuous PCCOC was small in magnitude, even though the coefficients are statistically significant for years 2 and 3 (Table 2). For example, the effect of the demonstration on provider-level PCCOC in years 2 and 3 is −0.8 percentage points (p = 0.001) for the continuous UPC outcome measures. The decreases are larger in magnitude for the practice-level continuous UPC index measure. For example, the effect of the demonstration on the practice-level continuous UPC outcome measure is −1.3 percentage points (p < 0.001). The binary measure shows a similar pattern (Table 3), with both the provider and practice levels decreasing over time and the practice dropping more than the provider level, and no practical effect of the demonstration.

Some of the other coefficients in the regression models indicate associations with PCCOC. Advancing age (compared with < 65 years) is significantly associated with higher PCCOC for both the provider and practice levels. Being female or having a higher hierarchical condition categories (HCC) score (greater severity of illness) is associated with lower continuity at both the provider and practice levels. Participating in a CMS Shared Savings model or program is positively associated with provider-level, but not with practice-level, PCCOC.

PCCOC for subgroups

We hypothesized that the demonstration may affect particularly vulnerable groups differently. Across the analyses shown in Table 4, black beneficiaries in the demonstration sites showed improved COC across 2 of the 3 demonstration years relative to white beneficiaries at the provider level. FQHCs with 5–14 service delivery sites showed significant declines in provider-level UPC scores (for years 1 and 2) and practice-level UPC scores (for years 1, 2, and 3) compared to FQHCs with less than 5 service sites.

Discussion

Our study finds that in the year prior to the Demonstration’s onset, beneficiaries attributed to both the demonstration and comparison FQHCs already had high levels of PCCOC as measured by the UPC index. The continuous UPC index measure was over 0.70 for the provider level and over 0.80 at the practice level for both the comparison and demonstration practices. These UPC values are higher than those reported in published studies spanning multiple practice settings: Previous reports note provider-level UPC scores of 0.59 for practices caring for type 2 diabetic patients (Weir et al. 2016), of 0.69 for adult primary care patients (Ionescu-Ittu et al. 2007), and of 0.66 for geriatric primary care patients (Rodriguez et al. 2008). The higher baseline UPC index scores observed in our study may reflect characteristics of FQHCs and their efforts to promote team-based and continuous care (Quyen et al. 2011; Shi et al. 2013; Shi et al. 2003; Starfield et al. 2005).

An important finding of this paper is that practice-level PCCOC is higher at all time points than provider-level PCCOC. Strategies adopted by FQHCs to improve access and quality are likely to preserve or enhance practice-level PCCOC. If the regular provider is not available, FQHCs may substitute another team-based provider, resulting in a lower provider-level UPC index but not impacting the UPC index at the practice level. Increased use of electronic health records also allows multiple providers within the same practice to see the same patient more seamlessly. Additionally, FQHCs seek to accommodate urgent care needs, and offering same-day appointments could further reduce provider-level continuity.

For both groups, the UPC scores declined slightly across the 3-year CMS FQHC Demonstration, similar to previous studies that also found mixed results from initiatives to improve care coordination for Medicare beneficiaries (Peikes et al. 2009; Sinaiko et al. 2017). Given that FQHCs were already showing high levels of COC, this type of small decline may be inevitable. Many FQHCs adopted strategies that had potential to decrease both provider-level and practice-level COC, while improving access.

We find nearly identical values for demonstration and comparison sites at each point in time for both provider- and practice-level UPC indexes. This finding may reflect both demonstration and comparison sites implementing similar strategies to enhance PCCOC. By the end of the demonstration, approximately 37% of comparison sites had achieved some level of PCMH recognition compared with 84% of demonstration sites (Timbie et al. 2017). In our study, we observed both demonstration and comparison sites expanding hours, increasing staff, building teams to support primary care, and conducting patient- and community-level outreach. External funding from several other sources provided incentives for FQHCs to implement these strategies (Kahn et al. 2017; Timbie et al. 2017).

In subgroup analyses, higher levels of patient comorbidity are associated with lower continuity at both the practice and the provider levels. Finally, we found that continuity improved for black Medicare beneficiaries during the Demonstration. It is not clear why improvements were not observed for other subgroups. It could be that all FQHCs seek to improve care for underserved groups, so the differences between demonstration and comparison groups were minimal.

Limitations

In addition to the limitations of the COC measures noted in the methods section, it is not clear how to translate marginal changes in the COC score with meaningful impacts on beneficiaries’ experience of care coordination and resulting outcomes. Patient-reported care coordination may differ from claims-based PCCOC. However, claims-based measures do provide a comprehensive look at patterns of care. In the future, pairing quantitative findings with qualitative interviews of beneficiaries and providers about whether they perceive increases in continuity and whether there are impacts on health outcomes, or spending would be useful. Other limitations of the evaluation of the model itself have been described elsewhere (Kahn et al. 2017; Timbie et al. 2017), including a slower than anticipated achievement of Level 3 recognition in the demonstration sites, and practice improvements occurring in the control group over the same time period. Medicare beneficiaries represent a small, but growing, portion of FQHCs’ overall patient panel, and the demonstration payments for increased care coordination activities may not have been large enough to incentivize practice changes that significantly improved COC.

Conclusion

Consistent with FQHCs’ mission to improve access to care, our analyses show that Medicare FQHC users are achieving high levels of continuity of care at both demonstration and comparison site FQHCs. Overall, our demonstration and comparison site analyses demonstrated declines over time in provider-and practice-level COC, but the magnitudes of the changes were small.

References

AAAHC (2011) FY 2011 patient-centered medical home (PCMH) supplemental funding opportunity. Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care, Inc. https://www.aaahc.org/Global/pdfs/Medical%20Home/PCMH_Funding.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2016

American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, Association AO (2007) Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMH-joint.Pdf. Accessed January 2018

Amjad H, Carmichael D, Austin AM, Chang CH, Bynum JP (2016) Continuity of care and health care utilization in older adults with dementia in fee-for-service Medicare. JAMA Intern Med 176(9):1371–1378. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3553

Bailey MJ, Goodman-Bacon A (2015) The War on Poverty’s experiment in public medicine: community health centers and the mortality of older Americans. Am Econ Rev 105:1067–1104. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120070

Bice TW, Boxerman SB (1977) A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care 15:347–349

Chang CH, Lewis VA, Meara E, Lurie JD, Bynum JP (2016) Characteristics and service use of Medicare beneficiaries using federally qualified health centers. Med Care 54:804–809. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000564

CMMI (2018) Accountable care organizations (ACOs): general information. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ACO. Accessed 25 Jan 2018

CSSP (2011) Summary of affordable care act funding opportunities. Center for the Study of Social Policy. https://www.cssp.org/community/neighborhood-investment/other-resources/Opportunities-for-Communities-in-the-Affordable-Care-Act-September-2011.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2016

DuGoff EH, Bandeen-Roche K, Anderson GF (2016) Relationship between continuity of care and adverse outcomes varies by number of chronic conditions among older adults with diabetes. J Comorbid 6:65–72. https://doi.org/10.15256/joc.2016.6.76

Eriksson EA, Mattsson LG (1983) Quantitative measurement of continuity of care - measures in use and an alternative approach. Med Care 21:858–875. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198309000-00003

HRSA (2016) About the health center program. Health Resources & Services Administration. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/index.html. Accessed August 23 2016

HRSA (2017a) Health center controlled networks. Health Resources & Services Administration. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/qualityimprovement/strategicpartnerships/hccn.html. Accessed Jan 1 2017

HRSA (2017b) What is a Health Center? Health Resources & Services Administration. https://www.bphc.hrsa.gov/about/what-is-a-health-center/index.htmlv. Accessed Jan 1 2017

HRSA (2018) HRSA accreditation and patient-centered medical home recognition initiative. Health Services & Resources Administration. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/qualityimprovement/clinicalquality/accreditation-pcmh/index.html. Accessed Jan 1 2018

Hussey PS, Schneider EC, Rudin RS, Fox DS, Lai J, Pollack CE (2014) Continuity and the costs of care for chronic disease. JAMA Intern Med 174:742–748. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.245

Ionescu-Ittu R et al (2007) Continuity of primary care and emergency department utilization among elderly people. CMAJ 177:1362–1368. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.061615

Jackson GL et al (2013) The patient-centered medical home. Ann Intern Med 158:169–178. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579

Kahn KL et al (2017) Evaluation of CMS’s federally qualified health center (FQHC) advanced primary care practice (APCP) demonstration: final report. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Kahn KL et al (2015a) Evaluation of CMS’ FQHC APCP demonstration: final first annual report. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Kahn KL et al (2015b) Evaluation of CMS’s federally qualified health center (FQHC) advanced primary care practice (APCP) demonstration: final second annual report. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Liss DT, Chubak J, Anderson ML, Saunders KW, Tuzzio L, Reid RJ (2011) Patient-reported care coordination: associations with primary care continuity and specialty care use. Ann Fam Med 9:323–329. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1278

Maarsingh OR, Henry Y, van de Ven PM, Deeg DJ (2016) Continuity of care in primary care and association with survival in older people: a 17-year prospective cohort study. British J General Pract: J Royal College General Pract 66:e531–e539. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X686101

Mahmud A et al (2018) Examining differential performance of 3 medical home recognition programs. Am J Manag Care 24:334–340

Mukamel DB, White LM, Nocon RS, Huang ES, Sharma R, Shi LY, Ngo-Metzger Q (2016) Comparing the cost of caring for Medicare beneficiaries in federally funded health centers to other care settings. Health Serv Res 51:625–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12339

NACHC (2016) A sketch of community health centers: Chartbook, August 2016. National Association of Community Health Centers. http://nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Chartbook16.pdf. Accessed August 23 2016

NCQA (2016) Patient-Centered Medical Home Recognition. National Committee for Quality Assurancehttp://www.ncqa.org/programs/recognition/practices/patient-centered-medical-home-pcmh. Accessed August 23 2016

NQF (2010) Preferred practices and performance measures for measuring and reporting care coordination. National Quality Forum. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2010/10/Preferred_Practices_and_Performance_Measures_for_Measuring_and_Reporting_Care_Coordination.aspx. Accessed August 23 2016

PCPCC (2011) Core values, community connections: care coordination in the medical home. Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative

Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R (2009) Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among medicare beneficiaries 15 randomized trials. JAMA 301:603–618. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.126

Perry RJ, McCall N, Wensky SG, Haber SG (2016) Care continuity in a patient- centered medical home setting. Research Triangle Institute Press Publication No RR-0026-1602. RTI Press, Research Triangle Park NC

Pollack CE, Hussey PS, Rudin RS, Fox DS, Lai J, Schneider EC (2016) Measuring care continuity a comparison of claims-based methods. Med Care 54:E30–E34. https://doi.org/10.1097/Mlr.0000000000000018

Quyen NM, Shi LY, Hayashi S, Daly C, Sharma R, Politzer R (2011) Reducing disparities in accessing primary care: the role of health centers. J Gen Intern Med 26:S168–S168

Rodriguez HP, Marshall RE, Rogers WH, Safran DG (2008) Primary care physician visit continuity: a comparison of patient-reported and administratively derived measures. J Gen Intern Med 23:1499–1502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0692-z

Romaire MA, Haber SG, Wensky SG, McCall N (2014) Primary care and specialty providers an assessment of continuity of care, utilization, and expenditures. Med Care 52:1042–1049. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000246

Shi L, Lebrun-Harris LA, Parasuraman SR, Zhu J, Ngo-Metzger Q (2013) The quality of primary care experienced by health center patients. J Am Board Fam Med 26:768–777. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.130062

Shi L, Lee DC, Chung M, Liang H, Lock D, Sripipatana A (2017) Patient-centered medical home recognition and clinical performance in U.S. community health centers. Health Serv Res 52:984–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12523

Shi L et al (2015) Patient-centered medical home capability and clinical performance in HRSA-supported health centers. Med Care 53:389–395. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000331

Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J, Politzer R, Regan J (2003) Primary care quality: community health center and health maintenance organization. South Med J 96:787–795. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.SMJ.0000066811.53167.2E

Sinaiko AD et al (2017) Synthesis of research on patient-centered medical homes brings systematic differences into relief. Health Affair 36:500–508. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1235

Smedby B, Smedby O, Eriksson EA, Mattsson LG, Lindgren A (1984) Continuity of care. an application of visit-based measures. Med Care 22:676–680. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198407000-00010

Smedby O, Eklund G, Eriksson EA, Smedby B (1986) Measures of continuity of care — a register-based correlation study. Med Care 24:511–518

Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J (2005) Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 83:457–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

Timbie JW et al (2017) Implementation of medical homes in federally qualified health centers. N Engl J Med 377:246–256. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1616041

Weir DL, McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Eurich DT (2016) The interplay between continuity of care, multimorbidity, and adverse events in patients with diabetes. Med Care 54:386–393. https://doi.org/10.1097/Mlr.0000000000000493

Wright B, Potter AJ, Trivedi A (2015) Federally qualified health center use among dual Eligibles: rates of hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Health Aff (Millwood) 34:1147–1155. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0823

Acknowledgements

Funding support: funding was provided by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, (Contract: HHSM-500-2005-00028I, Task # T0008). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This research involved secondary data, and the RAND IRB determined this study exempt. As such, informed consent was not necessary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

APPENDIX A: Methodological Notes

APPENDIX A: Methodological Notes

Regression Models

For all analyses, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to model the relationship between participation in the demonstration and the UPC index, while controlling for beneficiary- and site-level characteristics that may influence continuity of care independent of the demonstration. GEE allows the selection of family and link functions, and accounts for repeated observations on the same beneficiaries over time. We used a Gaussian distribution with an identity link for the continuous UPC models, and binomial distribution with a log link for the binary UPC models. We adjusted standard errors for clustering of beneficiary responses over time using the Huber–White sandwich estimator.

The coefficients of interest are the interactions on the indicator for the demonstration group and the year indicators, as shown in the following equation:

The interpretation of the main coefficient of interest (β3Demo*Yearijt) is how much the UPC index value changed in the demonstration group over time compared to the comparison group. We controlled for beneficiary (X) and site-level (Z) characteristics that may influence continuity for beneficiaries (Timbie et al. 2017). Beneficiary characteristics include: age, race (White, Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other/unknown), gender, whether the beneficiary was also eligible for Medicaid, whether the beneficiary was disabled, whether the beneficiary was institutionalized, the number of visits to primary care providers per year, and the beneficiary’s hierarchical condition category (HCC) score (a measure of health risk).

We also include several site-level characteristics: whether the clinic was in a rural area (metro, non-metro urban, non-metro rural), region (Central, Mid-Atlantic, Northeast, Southeast, West, West-Central), household poverty in the Census tract; the number of delivery sites associated with the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), the number of years in operation, the total number of providers and Medicare beneficiaries associated with the FQHC at baseline, and whether the FQHC was also participating in other payment or delivery reform programs at the same time. These other payment and delivery system reform programs include the following: 1) whether the site received funds as part of the Affordable Care Act’s building capacity, New Access Point and/or Immediate Facility Improvement grant (CSSP 2011), 2) Health Center Controlled Networks funding for health IT collaborations between health centers (HRSA 2017), 3) quality accreditation from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the Joint Commission, or the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Care (HRSA 2018), 4) whether the site participated in either the Pioneer Accountable Care Organization program or the Medicare Shared Savings Program (CMMI 2018), 5) PCMH supplemental funding (one-time grant of $35,000 for PCMH transformation in 2011) (AAAHC 2011), and finally, 6) the HRSA PCMH initiative which covered the cost of applying for PCMH recognition.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buttorff, C., Timbie, J.W., Lavelle, T.A. et al. Do interventions promoting medical homes in FQHCs improve continuity of care for Medicare beneficiaries?. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 255–267 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01090-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01090-4