Abstract

Aim

Sociomedical risks are common problems during pregnancy and can have serious health consequences for both mother and child. They are frequently underestimated within prenatal care programmes, although routine screening could help identify women in need of additional support. The aim of this article was to systematically summarise risk assessment and screening recommendations for mental health problems, depression, substance misuse and intimate partner violence during pregnancy using evidence-based guidelines, in order to provide a decision support for healthcare professionals and policy-makers.

Subjects and methods

A systematic literature search in two guideline databases was carried out and websites of international institutions developing evidence-based guidelines were searched. Guidelines from Western, industrialised countries, published in English or German since 2007 and providing recommendations for sociomedical screenings during pregnancy were included. Furthermore, guidelines had to be based on a systematic literature search in at least two databases and had to involve recommendations explicitly linked to the evidence.

Results

Sixteen guidelines, developed by nine institutions from Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia, met the inclusion criteria. The majority of the guidelines recommended routine assessment, although some conflicting recommendations were found for depression, illicit drug use and violence.

Conclusion

Our research findings suggest that screening or assessment for the analysed risk factors is advisable. However, the assigned grades of recommendation reflect that the evidence base is limited. Further research should also concentrate on evaluating different screening methods, as there was little consensus on the ideal screening test.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sociomedical and psychosocial risk factors are common problems during pregnancy and in the postpartum period and can dramatically affect maternal and child health. In this article, we focused on mental health problems, depression, violence and substance misuse as sociomedical risks. In high-income countries, around 10–15 % of women suffer from postpartum depression, according to the World Health Organization (WHO 2009). Research suggests that one in ten women experience depression, anxiety or both during pregnancy and one in six women are affected in the year following birth (beyondblue 2011). In the United States (US), it is estimated that around 8 % of women drink alcohol during pregnancy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012) and that 4 % use illicit drugs (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2007). In a retrospective cohort study from the US, 2 % of the surveyed women reported illegal or nonmedical drug use and 4 % reported alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Coker et al. 2012). In many European countries, more than 10 % of pregnant women smoke (EURO-PERISTAT 2013). Prevalence rates for intimate partner violence during pregnancy range from 3 to 25 % (Perttu and Kaselitz 2006); in another publication, it was estimated that one out of four women worldwide are physically or sexually abused while pregnant (Heise et al. 2002).

Routine screening measures can help identify women in need of additional support and are therefore a crucial part of prenatal care. Prenatal care aims at detecting risk factors and preventing health problems in children and their mothers and is considered one of the most important healthcare services. However, the WHO report also stated that unneeded and unproven interventions are often provided to women with normal pregnancies (Banta 2003). Programmes for antenatal care vary significantly. As has been shown in a study by Bernloehr et al. (2005), in addition to the number of screening measures during pregnancy, the content of antenatal examinations differs substantially in European countries. Winkler et al. (2013) noted that the majority of the most common health threats, affecting around 10 % of pregnant women, are sociomedical issues, which are associated with socioeconomic, environmental and lifestyle factors. A survey amongst eight European countries demonstrated that assessment and screening for these health threats is currently only partially present in their national prenatal care policies (Winkler et al. 2013).

Evidence-based guidelines analyse and evaluate the currently available evidence and carefully assess the balance between benefits and potential harms of screening measures. They not only outline the evidence on a specific healthcare topic, but give explicit practice recommendations, for example, whether or not to offer routine assessment and screening (Muche-Borowski and Kopp 2011).

In the context of a larger project on the “re-orientation of the Austrian parent–child preventive care programme” on behalf of the Austrian Ministry of Health, we conducted a comprehensive systematic overview of screening recommendations during pregnancy and early childhood (until the age of 6 years) from evidence-based guidelines (Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Health Technology Assessment 2013). This article aims at summarising and analysing screening recommendations dealing with sociomedical risk factors (mental health problems, depression, substance misuse and intimate partner violence), as these are important public health problems with serious consequences that are, compared to other (medical) conditions, often underestimated within prenatal care.

Methods

Literature search

In June 2012, a systematic literature search for evidence-based guidelines was conducted in two guideline databases: the Guidelines International Network (GIN) and the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). In order to identify all potentially relevant screening guidelines, a broad search strategy was applied: in the GIN database, the search term “screening” was used and in NGC, “screening” was selected as the “guideline category”. This systematic literature search was supplemented by a comprehensive hand search on the web pages of international institutions that develop evidence-based guidelines. The hand search was conducted from June–December 2012 and updated in October 2013. A list of searched websites is provided in Table 1. All references were exported to a software tool for managing bibliographies (EndNote® X5).

Inclusion criteria

We included evidence-based guidelines from Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand, published in English or German since 2007 and dealing with (routine) risk assessment and screening measures (see Table 2). We chose the publication time frame of 5 years following the inclusion criteria of the NGC database (NGC 2014) and we decided to include only evidence-based guidelines that were developed according to a sound methodological process. Hence, guidelines had to meet the following methodological quality criteria: they had to be based on a systematic literature search in at least two databases and they had to formulate recommendations that were explicitly linked with the underlying evidence.

Guideline selection process

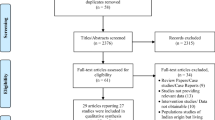

We identified 209 references in GIN and 446 references in NGC through the systematic search, as well as an additional 94 guidelines through the comprehensive hand search. After duplicates were removed, a total of 660 references were screened and assessed for inclusion using a three-step approach by two researchers. First, the titles of the guidelines were screened, then the references were excluded if the language was not English or German, if the guidelines were not developed in Europe, North America, Australia or New Zealand or if the thematic focus of the guideline was not relevant to pre- or postnatal care (e.g. cancer screening). In the second step, we screened the summaries of the guidelines that were mostly provided by the NGC database. Guidelines were excluded if they explicitly focused only on screenings for specific target groups (e.g. women or children with pre-existing diseases). Furthermore, they had to fulfil the previously stated methodological quality criteria. In the last step of the guideline selection, we checked the full texts with regard to the inclusion criteria. In cases of disagreement, we achieved consensus through discussion or by involving a third researcher. We identified a total of 138 guidelines for all screening measures during pregnancy and early childhood. For the focus of this article (sociomedical risk factors), we conducted an additional specific hand search for relevant guidelines on the websites of guideline-developing institutions (see Table 1). A total of 16 guidelines provided recommendations for screening and risk assessment for sociomedical risk factors. Figure 1 illustrates the guideline selection process.

Data extraction

The data extraction covered the recommendation—screening/risk assessment recommended (✓), not recommended (X), or unclear/no recommendation (?)—the grade of recommendation, the recommended timing of screening and the recommended methods. An overview of the recommendation grades and their meanings for each of the included guideline institutions is provided in Table 3.

Results

In total, 16 full text guidelines from 9 institutions fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included for analysis. We identified three guidelines from the United Kingdom (UK; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE 2008), the US (Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense VA/DoD 2009a) and Australia (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council AHMAC 2012) that covered prenatal care in general and, therefore, provided recommendations for all of the analysed health threats. Six guidelines, from the UK (NICE 2007; UK National Screening Committee UK NSC 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network SIGN 2012), Australia (beyondblue 2011), the US (VA/DoD 2009b) and Canada (Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care CTFPHC 2013) focused on mental health problems and included recommendations related to mental health assessment and depression screening. Concerning screening or assessment for substance misuse (alcohol, smoking, illicit drugs), another five specific guidelines were identified that had been developed by Canadian (Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada SOGC 2010; 2011) and US institutions (US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF 2008, 2009, 2013a). Finally, we analysed two guidelines from the US (USPSTF 2013b) and the UK (UK NSC 2006), providing recommendations for identifying pregnant women affected by domestic violence.

Mental health and depression

While all included guidelines agreed on incorporating an assessment for current or past psychiatric illness (including a family history) in prenatal care, we identified conflicting recommendations related to routine screening for depression. As can be seen in Table 4, five guidelines (NICE 2007; VA/DoD 2009a; beyondblue 2011; AHMAC 2012; SIGN 2012) provided recommendations regarding a risk assessment for mental health problems, including asking for family history or woman’s own history of psychiatric illness as well as for present state of mental health. All of the included guidelines gave a recommendation in favour of this assessment. On the whole, they also agreed on the recommended point of time (early in pregnancy) as well as on the recommended methods (anamnesis, family history). Concerning screening for depression (in the prenatal period, as well as postpartum), the recommendations were inconsistent. Five guidelines (NICE 2007; VA/DoD 2009b; beyondblue 2011; AHMAC 2012; SIGN 2012) made a pro-screening recommendation, while two (UK NSC 2011; CTFPHC 2013) gave “contra” recommendations. There is no consensus on recommended screening methods, either: the included guidelines mentioned the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the Whooley Questions, and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). However, all guidelines recommending routine screening for depression agreed on the point that screening should be offered at least once during pregnancy and at least once after birth. Two guidelines recommended against routine screening for depression: the Canadian guideline (CTFPHC 2013) gave a “weak recommendation” that no routine screening should be offered, but stated that clinicians should be alert to the possibility of depression. The UK NSC (2011) did not recommend systematic population screening, either, but referred to the clinical practice guideline by NICE and suggested that health professionals should be alert and manage postpartum depression according to the available guidance.

Substance misuse

The reviewed guidelines clearly recommended assessment for tobacco use and alcohol consumption, but were not consistent regarding screening for illicit drug use. All included guidelines (NICE 2008; USPSTF 2009; VA/DoD 2009a; SOGC 2011; AHMAC 2012) provided a pro-screening recommendation related to smoking during pregnancy. Most guidelines suggested that assessing smoking status should take place at the first prenatal care visit. The recommendations on assessment for alcohol use (VA/DoD 2009a; SOGC 2010; AHMAC 2012; USPSTF 2013a) are also homogeneous. Possible screening methods mentioned in the guidelines are the T-ACE (“Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut down, Eye-opener”) and the TWEAK (“Tolerance, Worry, Eye-opener, Amnesia, Cut down”) questionnaires, as well as specific interview questions. There was no consensus concerning assessment for illicit drug use. Three guidelines (VA/DoD 2009a; SOGC 2011; AHMAC 2012) recommended screening, whereas one institution (USPSTF 2008) stated that there was insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms. Moreover, there is uncertainty about the best screening method (Table 5).

Intimate partner violence

Although most of the reviewed guidelines (three out of five: VA/DoD 2009a; AHMAC 2012; USPSTF 2013b) advocated routine assessment for domestic violence, we also found contrary recommendations. One institution (UK NSC 2006) stated that a systematic population screening programme is not recommended, whereas another (NICE 2008) recommended that healthcare professionals should be alert to signs and symptoms of domestic violence, but did not encourage systematic screening. The guidelines in favour of routine assessment did not agree on the recommended screening methods; suggestions included the use of “Three simple, direct questions” (VA/DoD 2009a) or various standardized questionnaires (USPSTF 2013b; Table 6).

Grades of recommendation

The assigned recommendation grades indicate that the evidence for the analysed preventive interventions is not generally very good. The highest grade, A, was only assigned to three of the recommendations related to screening for tobacco use. The other recommendations are mostly based on grade B or lower grades or the recommendations are “consensus-based” or “good practice points” (see Table 3 for an overview of grades and their definitions). The UK NSC uses 22 criteria instead of recommendation grades: neither postpartum depression screening nor assessment for domestic violence have met all of the UK NSC’s “Criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme” (UK NSC, no date).

Discussion

The analysis of recommendations from evidence-based guidelines related to sociomedical and psychosocial factors during pregnancy suggests that screening for these conditions is advisable. Although we also found contrary recommendations for depression, illicit drug use and domestic violence, routine screening was still recommended by the majority of the identified evidence-based guidelines. From a total of 30 recommendations, analysed for all sociomedical factors, 25 were pro-screening.

Nevertheless, the assigned grades of recommendation show that the evidence seems to be rather low overall; some of the recommendations are even referred to as “consensus-based”. The exception is assessment for tobacco use, where we found three recommendations with the highest grade of A. This means that, although the evidence base for most of the screening measures covered in this article is apparently not very well established, most institutions concluded that a routine screening should take place anyway. Interestingly, the UK NSC, which, unlike the other institutions, develops policies rather than clinical (practice) guidelines, released “contra screening” recommendations, both for postpartum depression and domestic violence. However, in the case of postpartum depression, the UK NSC suggested that healthcare professionals should be alert and manage postpartum depression according to NICE (UK NSC 2011). The reason for the decision against screening, however, is that some of the 22 UK NSC appraisal criteria were not fulfilled. These criteria address the condition, the test, and the treatment, as well as the whole screening programme and it is mandated that, for example, evidence be available from high quality randomised controlled trials for the effectiveness of the screening programme in reducing mortality and morbidity (UK NSC, no date). According to the evaluation review, the UK NSC concluded that this criterion, amongst others, was not met for postpartum depression screening (Hill 2010).

Whereas included guidelines mostly agreed on the recommended timing of screening, there was, for most conditions, no consensus on the recommended screening method. For example, different tests were mentioned to screen for depression: four of the five pro-screening guidelines mentioned the EPDS, either as the recommended screening method (beyondblue 2011; AHMAC 2012) or as a possibility (VA/DoD 2009b; SIGN 2012). Other recommended tools included the Whooley Questions (NICE 2007; SIGN 2012) and the PHQ-2 (VA/DoD 2009b). A literature review (Gjerdingen and Yawn 2007) on this topic cited the EPDS as the most extensively studied screening tool, but came to the conclusion that further studies are needed to identify the ideal screening test for postpartum depression. The UK NSC report found a lack of consensus regarding the cut-off point to determine if the EPDS is considered to be positive or negative, which has implications on sensitivity and specificity (Hill 2010). However, all five of the pro-screening guidelines (NICE 2007; VA/DoD 2009b; beyondblue 2011; AHMAC 2012; SIGN 2012) agreed that screening for depression should take place both during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Guidelines providing recommendations for tobacco use screening did not recommend a specific test, but mentioned that smoking status should be “assessed”, “discussed” or “asked” about. This stands in opposition to the public health guidance by NICE (2010), which recommends using a carbon monoxide test, administered by a midwife at the first visit during pregnancy and at subsequent appointments. It is described as an immediate and non-invasive test to assess smoking status, although the optimal cut-off point is unclear. There was also no clear consensus regarding methods for assessing alcohol use, although the T-ACE and the TWEAK were mentioned by all included guidelines (VA/DoD 2009a; SOGC 2010; AHMAC 2012; USPSTF 2013a). Information on screening tools for assessing drug abuse was not specific; guidelines recommended “assessment of psychosocial factors” (AHMAC 2012), “open-ended, non-judgmental questioning” or the Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) tool (incorporates various questions to identify maternal drug use, as well as family violence and depression) (SOGC 2011) and a “self-report method” (VA/DoD 2009a).

Conflicting recommendations were found for domestic violence, drug abuse and depression screenings. Two (out of seven) guidelines (UK NSC 2011; CTFPHC 2013) advised against routine depression screening, but suggested that clinicians should be alert to signs and symptoms of depression. The UK NSC, despite its contra screening recommendation, concluded in its 2010 evaluation of NSC criteria that postpartum depression meets the criterion of an important health problem because it is common, has serious consequences and is usually not adequately detected during routine clinical practice (Hill 2010). The review by Gjerdingen and Yawn (2007) pointed out that screening alone may not have effects on clinical outcomes, as long as there are no care systems in place that provide effective treatment and follow-up of affected women. Out of four guidelines dealing with routine screening for illicit drug use, one US guideline (USPSTF 2008) did not release a recommendation due to insufficient evidence. Three of five analysed guidelines (from the US and Australia; VA/DoD 2009a; AHMAC 2012; USPSTF 2013b) supported routine assessment for intimate partner violence during pregnancy and each was assigned a recommendation grade of B, which stands for “a body of evidence that can be trusted to guide practice in most situations” (AHMAC 2012), “at least fair evidence that the intervention improves health outcomes” (VA/DoD 2009a) and “high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or of moderate certainty that net benefit is moderate to substantial” (USPSTF 2013b). The UK guidelines (UK NSC 2006; NICE 2008) did not recommend a systematic violence screening. The NICE guideline emphasized in its 2008 publication that evaluations of interventions for domestic violence are urgently needed, because there is insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of interventions for at-risk women. Nevertheless, NICE concluded that effective screening tools for domestic violence exist and that routine assessment is acceptable to women (NICE 2008). A survey among German women showed high acceptance of inquiry for intimate partner violence during antenatal care: 56 % supported routine screening, whereas 36 % preferred case-based inquiry. This finding was reported to be in line with previous studies that found higher acceptance of violence screening during pregnancy than during general care (Stöckl et al. 2013). An Australian study also showed high acceptance of routine assessment for alcohol and drug use amongst pregnant women; only 15 % of surveyed women were uncomfortable about being screened (Seib et al. 2012).

Other relevant aspects in the context of sociomedical screenings are, firstly, the most suitable setting in which the healthcare service should be delivered (e.g. during home visits, in the hospital, in a medical practice, etc.) and secondly, which healthcare professionals should undertake screening. Several barriers still seem to exist regarding depression screening, such as insufficient training and lack of time on the part of the physician, as well as social stigma (Gjerdingen and Yawn 2007). According to the findings of the UK NSC evaluation, the EPDS was found to be acceptable to women when the test was undertaken at home by a trained health visitor (Hill 2010). Generally, women of lower socioeconomic status are more often affected by mental health disorders, substance abuse and violence, and are less likely to take part in screenings than women of a higher socioeconomic status. Therefore, in several countries, screening measures are provided in home visits, which are undertaken by professional health visitors with the main advantage of reaching pregnant women and families that otherwise might not participate in the screening programme (Winkler et al. 2013). Regarding involved health professionals, there are also different approaches: whereas some countries include, for example, midwives, public health nurses or family nurses, in others, physicians are primarily responsible for prenatal care (Winkler et al. 2013).

Limitations

Our aim was to summarise recommendations from high-quality guidelines based on a sound methodological approach, rather than on expert consensus. Most guidelines identified through the literature search are so-called “clinical (practice) guidelines”. Other sources of information that could also contain valuable information on assessment for sociomedical and psychosocial factors are therefore missing in this analysis.

Additionally, we considered only those sociomedical risks for which we identified screening recommendations. Other important social determinants of health, such as lack of adequate housing, financial resources, or social support, are therefore not covered in this analysis.

We focused on risk assessment and screening measures, i.e. on the identification of pre-existing risk factors or diseases. Other approaches, such as health promotion and primary prevention, are equally important and should also be taken into account, in order to prevent risks in the first place.

Conclusion

On the basis of this analysis of recommendations from evidence-based guidelines, we conclude that screening for depression and mental health problems, substance misuse and domestic violence is generally advisable as a part of prenatal care. For most conditions, however, no agreement exists regarding the best screening methods. As the analysed sociomedical risk factors that affect many women during pregnancy can result in serious consequences for both mother and child, the majority of the identified evidence-based guidelines recommended routine screening, despite a lack of high-quality evidence in some areas. Further research is urgently needed to strengthen the evidence base. In the context of the implementation of a new screening measure into existing prenatal care programmes, an accompanying evaluation could be a reasonable way to gather more information about benefits and potential harms of the screening measures, as well as about important factors such as ideal screening methods.

References

Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) (2012) Clinical practice guidelines: antenatal care—module 1. http://www.health.gov.au/antenatal. Accessed 3 April 2014

Banta D (2003) What is the efficacy/effectiveness of antenatal care and the financial and organizational implications? Health Evidence Network report. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

Bernloehr A, Smith P, Vydelingum V (2005) Antenatal care in the European Union: a survey on guidelines in all 25 member states of the Community. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 122:22–32

beyondblue (2011) Clinical practice guidelines for depression and related disorders—anxiety, bipolar disorder and puerperal psychosis—in the perinatal period: a guideline for primary care health professionals. beyondblue, Melbourne, Australia. https://www.bspg.com.au/dam/bsg/product?client=BEYONDBLUE&prodid=BL/0891&type=file. Accessed 3 April 2014

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) (2013) Recommendations on screening for depression in adults. http://www.cmaj.ca/content/suppl/2013/07/29/cmaj.130403.DC3/depress-update.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age: United States, 2006–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (MMWR) 61:534–538

Coker AL, Garcia LS, Williams CM, Crawford TN, Clear ER, McFarlane J, Ferguson JE (2012) Universal psychosocial screening and adverse pregnancy outcomes in an academic obstetric clinic. Obstet Gynecol 119:1180–1189

Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense (VA/DoD) (2009a) VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of pregnancy. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/up/mpg_v2_1_full.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense (VA/DoD) (2009b) VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of major depressive disorder (MDD). http://www.healthquality.va.gov/mdd/mdd_sum09_c.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

EURO-PERISTAT Project with SCPE and EUROCAT (2013) European Perinatal Health Report: health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2010. http://europeristat.com/images/doc/Peristat%202013%20V2.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

Gjerdingen DK, Yawn BP (2007) Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J Am Board Fam Med 20:280–288

Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M (2002) A global overview of gender-based violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 78:5–14

Hill C (2010) An evaluation of screening for postnatal depression against NSC criteria. http://screening.nhs.uk/policydb_download.php?doc=181. Accessed 3 April 2014

Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Health Technology Assessment (2013) Re-orientation of the Austrian parent-child preventive care programme, parts I–IX. http://hta.lbg.ac.at/page/praevention-screening. Accessed 3 April 2014

Muche-Borowski C, Kopp I (2011) Wie eine Leitlinie entsteht. Z Herz Thorax Gefäßchir 25:217–223

National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) (2014) Inclusion criteria. http://www.guideline.gov/about/inclusion-criteria.aspx. Accessed 3 April 2014

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2007) Antenatal and postnatal mental health. The NICE guideline on clinical management and service guidance. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11004/30431/30431.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2008) Antenatal care: routine care for the healthy pregnant woman—clinical guideline. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11947/40145/40145.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2010) Quitting smoking in pregnancy and following childbirth: NICE public health guidance 26. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13023/49345/49345.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

Perttu S, Kaselitz V (2006) Addressing intimate partner violence: guidelines for health professionals in maternity and child health care. University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2012) Management of perinatal mood disorders: a national clinical guideline. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign127.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

Seib CA, Daglish M, Heath R, Booker C, Reid C, Fraser J (2012) Screening for alcohol and drug use in pregnancy. Midwifery 28:760–764

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) (2010) Alcohol use and pregnancy consensus clinical guidelines. http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/documents/gui245CPG1008E.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) (2011) Substance use in pregnancy. http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/documents/gui256CPG1104E.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014

Stöckl H, Hertlein L, Himsl I, Ditsch N, Blume C, Hasbargen U, Friese K, Stöckl D (2013) Acceptance of routine or case-based inquiry for intimate partner violence: a mixed method study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13:77

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2007) Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings. Rockville, MD

UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) (no date) Programme appraisal criteria: criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/criteria. Accessed 3 April 2014

UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) (2006) Domestic violence (pregnancy): The UK NSC policy on domestic violence screening in pregnancy. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/domesticviolence-pregnancy. Accessed 3 April 2014

UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) (2011) Postnatal depression: the UK NSC policy on postnatal depression screening in pregnancy. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/postnataldepression. Accessed 3 April 2014

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2008) Screening for illicit drug use: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdrug.htm. Accessed 3 April 2014

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2009) Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 150:551–555

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2013a) Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdrin.htm. Accessed 3 April 2014

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2013b) Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 158:478–486

Winkler R, Warmuth M, Piso B, Zechmeister-Koss I (2013) Towards a re-orientation of the Austrian ‘Parent–child preventive care programme’. J Public Health 21:583–592

World Health Organization (WHO) (2009) Mental health aspects of women’s reproductive health: a global review of the literature. WHO, Geneva

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tarquin Mittermayr, BA for conducting the systematic guideline search.

The Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Health Technology Assessment is funded by national research funds (The Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft) and by partner institutions (e.g. the Federation of Austrian Social Insurance Institutions and the Austrian Ministry of Health). This in-depth analysis of screening recommendations for sociomedical and psychosocial factors was carried out as decision support for the Austrian Ministry of Health within a larger project aimed at the re-orientation of the Austrian parent–child preventive care programme.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reinsperger, I., Winkler, R. & Piso, B. Identifying sociomedical risk factors during pregnancy: recommendations from international evidence-based guidelines. J Public Health 23, 1–13 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-015-0652-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-015-0652-0