Abstract

This paper investigates the effect of inward foreign investment on the relative employment of skilled labour. The extensive review of the empirical evidence shows that the results seem to be country-specific. Using Canadian industry-level panel data, the paper shows that most Canadian industries have experienced skill upgrading, and that foreign investment, as measured by FDI or majority ownership, has contributed to this development. Moreover, notwithstanding higher regulatory restrictions on foreign investment into Canadian services industries, foreign investment has had a similar impact on skill upgrading across both the services and non-services sectors. Finally, offshoring is found to only have a positive significant impact on skill upgrading in the services sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Increasing foreign direct investment (FDI) has become an important part of globalization in recent years, with generally agreed longer-term economic benefits to host countries. Nonetheless, FDI is one of the primary accused culprits of growing income inequality in the recipient countries, as it is often associated with “skill upgrading” (i.e., an increasing demand for skilled labour, relative to unskilled labour) and the resulting increase in relative wages for skilled labour.

There is broad agreement that a distinguishing feature of FDI or foreign affiliates of MNEs is their possession of firm-specific knowledge assets – patents, proprietary technology, trademarks, etc.– that can be exploited in host countries.Footnote 1 These assets provide the foreign affiliates with a technological knowledge advantage over domestically-owned firms. Thus, the higher knowledge (or technology) intensity of foreign-controlled firms has become a ‘stylized fact’ in the FDI literature. Given this fact, one could identify at least three important channels through which inward FDI can raise host-country demand for skills.

First, as a result of their alleged superior technological knowledge, foreign affiliates of MNEs are likely to be more skilled-labour intensive than national firms. The relative demand for skilled labour thereby tends to rise as multinationals grow in importance and substitute for the activity of national enterprises. Consequently, to the extent that advanced technologies are skill-biased, inward FDI shifts the demand for skilled labour outward for a given supply, and increases both relative wage and employment of these workers. A second channel is that foreign affiliates’ technological knowledge may spill over to local firms within the same industry via technical connections, business model copying and enhanced competition. As a result of these spillovers, relative demand for skilled labour also increases in the locally-owned firms, further raising aggregate demand for skills and increasing wage inequality. A third channel by which the demand for skilled labour would rise is through increased spending on capital. Implementing new technologies often involves making new capital investments (e.g., computers and office products). To the extent that capital and skills are complements in the production process, skill upgrading would arise not just directly from new technologies but also indirectly from the capital investments induced by these technologies.

On the other hand, there are also at least three reasons why inward FDI may not lead to skill upgrading. First, foreign affiliates may actually not employ more skilled workers in host countries; rather they may purposely come into industries with more skilled workers, in which case skill upgrading is the cause rather than the outcome of FDI. Second, as underlined in Bandick and Hansson (2009), technological capabilities of local firms may give rise to country-specific advantages and attract foreign firms. Thus, if technology sourcing is the reason for FDI, it is likely that the acquired domestic firms will keep the same skills mix after the foreign takeover, and thereby leaving the relative demand for skills unchanged. In other words, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) may differ from the other forms of FDI such as Greenfield investment in generating skill upgrading in host countries. Finally, Wu (2001) and Fajnzylber and Fernandes (2009) also raise the possibility of FDI being unskilled-biased as opposed to skilled-biased. For example, a relatively labour abundant country, such as China, may attract FDI that takes advantage of cheap unskilled labour. In that case, the net effect of inward FDI on the demand for skills would depend on the relative importance of skill-biased technology diffusion versus exploitation of the host country’s comparative advantage in the production of unskilled labour-intensive goods by foreign-owned firms.

Thus, it appears that inward FDI or the foreign-affiliate presence has various, and sometimes conflicting, effects on relative demand for skilled labour, which highlight the need for empirical work. In other words, the net effect of inward direct investment on skill upgrading is theoretically ambiguous without knowing the factors such as the type or motive behind the FDI. For many countries, empirical studies have explored this issue and found that the results seem to be country-specific. Previously, no study investigated this issue for Canada. Against this background, the purpose of this paper is twofold. First, it extensively reviews the empirical literature on FDI-induced skill upgrading in the recipient countries, distinguishing between the evidence for developed countries versus developing and transition countries. Second, using Canadian industry-level panel data, it contributes to the literature by investigating whether a foreign-affiliate presence (measured by FDI or foreign majority ownership) contributed to the relative employment of skilled individuals in Canada.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides an extensive review of the empirical evidence on the impacts of FDI on skill upgrading in the host countries. Section 3 outlines the empirical framework, describes the construction of variables and presents the empirical results. Finally, section 4 concludes the paper with a summary of the major findings.

2 Review of empirical literature

2.1 Developed countries

2.1.1 Foreign-affiliate activity and skill upgrading in U.S. manufacturing

Blonigen and Slaughter (2001) examine the impact of inward FDI flows and rising foreign-affiliate presence on skill upgrading within U.S. manufacturing. Using industry-level data, they find that inward FDI has not contributed to skill upgrading, and this finding is robust to different measures of foreign-affiliate activity (such as shares of employment, wages, assets and shipments) and different types of FDI (such as greenfield plants versus acquired ones). However, considering the case of Japanese inward FDI in particular, they report that while greater Japanese presence through acquisitions has no significant effect on skill upgrading, Japanese greenfield investment is found to be significantly correlated with lower, not higher, relative demand for skilled workers. They claim that this negative correlation accords with recent MNE models, which suggest that foreign affiliates focus on activities that are less skills-intensive than the activities of parent firms. Thus, if inward FDI brought new technologies into the U.S., they were not biased towards skilled labour.

2.1.2 Inward FDI and demand for skills in manufacturing firms in Sweden

Using firm-level data, Bandick and Hansson (2009) explore the impact of growing inward FDI and rising foreign-affiliate presence on skill upgrading in Swedish manufacturing. After separating the domestically-owned firms into non-MNEs and Swedish MNEs, they find that relative demand for skilled labour increases in non-MNEs acquired by foreigners, while there seems to be no effect on the relative demand for skills in acquired Swedish MNEs. They justify these findings on the grounds that technology transfers to non-MNEs by foreign acquiring firms are skills-biased, while technology sourcing is the essential motive behind foreign acquisition of Swedish MNEs. As mentioned above, if technology sourcing is the main reason for FDI, it is reasonable to assume that the acquired firms keep the same skill-mix after the takeover, leaving the relative demand for skills unaffected. Moreover, they report that the larger foreign presence has a positive impact on relative demand for skilled labour in non-acquired Swedish MNEs within the same industry, while it has no effect on non-MNEs not acquired by foreign firms. As a possible explanation, they argue that increased foreign ownership in an industry intensifies the competition for skills between foreign MNEs and Swedish MNEs, generally driving up the employment of skilled labour in Swedish MNEs.

2.1.3 FDI and the labour market in the U.K

Driffield and Taylor (2000) present a series of results concerning the labour-market impacts of inward FDI in the UK. They argue that one of the crucial impacts is to increase wage inequality via the use of relatively more skilled labour by foreign and domestic firms. This result is found to be a combination of two effects. First, the entry of MNEs increases the demand for skills in an industry or region, thus increasing wage inequality. Second, technology spillovers occur from foreign to domestic firms. As a result of these spillovers, relative demand for skilled workers increases in domestic firms, further contributing to the aggregate skill upgrading and wage inequality. Using panel data across UK manufacturing industries, Driffield and Taylor (2002) test whether inward FDI contributes to increasing the employment of skilled individuals. Focusing on the effect of spillovers, their results suggest that FDI has a positive impact on the relative demand for skills, even after controlling for the factors most commonly used to explain relative employment shifts – namely technological change (as measured by R&D intensity) and import intensity.

2.1.4 Multinational companies and wage inequality: the case of Ireland

Using pooled data on the Irish manufacturing sector, Figini and Gorg (1999) examine the impact of MNEs on wage inequality. They hypothesize that MNEs introduce a higher level of technology to the host country, which leads to an increase in the demand for skilled labour and wage inequality. Their empirical results indicate an inverted U-shape relationship between wage inequality and the presence of MNEs. In other words, as MNEs increase, wage inequality increases, reaches a maximum and then eventually decreases. The subsequent reduction in wage inequality is due to the fact that over time, indigenous firms learn new technologies by imitating the MNEs, and previously unskilled workers become skilled by working with the new technologies.

2.1.5 The impact of FDI on wages: Japanese manufacturing firms

Nakamura (2008) explores the impact of both inward and outward FDI on Japanese workers’ wages in manufacturing firms. Pertaining to inward FDI, he argues that it brings in new foreign technologies, employment and competition into the host country. Further, the higher skilled workers are more likely to benefit from FDI as foreign firms’ competitive advantage lies mostly in managerial skills and advanced technologies, which primarily require skilled workers. Although he finds no empirical evidence to support the above argument, the author reports that Japanese workers in general gain significantly in terms of wages if they work for firms that are at least 50 % owned by foreigners. This is consistent with the empirical finding that foreign-owned firms have a significant advantage in terms of productivity over their domestic counterparts. However, it is unclear if these wage gains from FDI are long lasting.

2.1.6 The effect of foreign acquisition on employment and wages: Finnish establishments

Huttunen (2007) investigates the effect of foreign acquisition on wages and employment of different skill groups, using panel data on Finnish establishments. The empirical results indicate that foreign acquisitions do have a positive effect on wages in all skill groups. The wage increase is not immediate, but occurs within one to three years after the acquisition. In terms of employment, the findings are mixed. A regression equation using the whole data shows that foreign acquisitions have no significant effect on the share of highly educated workers in the plant’s employment. But, the regression analysis on the matched sample indicates that there is a small negative impact on the share of highly educated workers after acquisitions. This decrease could be due to shareholders using takeover as an effective way to re-organize the company and dismiss non-value-maximizing managers.

2.1.7 The labor market effects of foreign-owned firms in Portugal

Using firm-level panel data in Portugal, Almeida (2007) investigates whether foreign investors acquire firms with high human capital or wages, or whether foreign acquisitions improve these outcomes. She finds that foreign-owned firms have a more educated workforce, and pay higher wages for a given workforce quality. However, by comparing the same firms before and after foreign acquisition, she finds that following an acquisition, the size of the firm increases but that there is no significant change in the human capital of the average worker. Moreover, the pre-foreign acquired firms are generally more similar to the foreign-controlled firms. Therefore, foreign investors acquire domestic firms with relatively high productivity and technological characteristics similar to their own. Another Portuguese study, by Tavares and Teixeira (2005), examines whether foreign ownership is a determinant of human capital intensity in technology-based firms. They find that foreign ownership has a positive relationship with the human capital intensity directly and indirectly when foreign ownership is considered jointly with R&D intensity and the frequency of contacts with universities.

2.1.8 Technology, MNE activity and skill upgrading in Italian manufacturing

Using industry-level data, Grasseni (2004) investigates whether skill-biased technological change and FDI play a role in explaining the skill upgrading in the Italian manufacturing industry. Specifically, the author distinguishes the effect of R&D on skill upgrading in foreign-owned firms located in Italy and Italian multinational firms investing abroad. The author finds a positive relationship between R&D and skill composition of the Italian labour force in foreign-owned firms that do R&D. This result is also confirmed using investment in intangible assets as an alternative measure of technological effort. Moreover, the same analysis conducted by distinguishing between low- and high-tech sectors shows a significant positive impact in low-tech sectors. One possible explanation could be that the R&D effort is biased towards skilled labour in low-tech sectors, where Italy is likely to have a comparative advantage. Another Italian study, by Piva and Vivarelli (2004), uses a panel of manufacturing firms and investigates the impact of three possible determinants: R&D, organizational change, and FDI on the ratio skilled to unskilled workers. They find that the FDI impact is positive (and mildly significant) on white-collar workers and negative on blue-collar workers.

To sum up, it emerges that despite the similarity between developed countries, it is difficult to draw a clear conclusion on the skill upgrading implications of inward foreign investment. The results of the reviewed studies suggest a positive, zero or even a negative impact of foreign investment on the demand for skills, depending on the countries.

2.2 Developing and transition countries

2.2.1 Wages, skills, and globalization in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic: an industry-level analysis

Crino (2005) analyzes the manufacturing sectors of Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. He provides a set of stylized facts regarding changes in the skill composition of the workforce and in the earning structure by skills that could be induced by trade flows and foreign presence through direct investment. All three countries have experienced sharp increases in earning inequality in almost all manufacturing industries. In Polish manufacturing industries, increasing (decreasing) FDI stocks are associated with higher (lower) shares of skilled labour in total wage bill and employment. However, in the transport equipments sector, the share of skilled labour in total employment is negatively correlated with FDI. For the other two countries, the author does not find clear evidence about the relation between FDI and the two labour market indicators.

2.2.2 Foreign direct investment and wage inequality

Using a panel data on more than 100 developing and developed countries, Figini and Gorg (2011) investigate the relationship between FDI and wage inequality. They find that the effect of FDI differs between developing and developed countries. Results for developing countries suggest a non-linear effect; wage inequality increases with inward FDI stock but the impact declines with further increases in FDI after a certain threshold. Specifically, when FDI is first introduced, it acts as a vehicle for new technology transfers into the host country, increasing the demand for skilled labour as well as wage inequality. Next, domestic firms will imitate the multinational’s technologies and consequently the previously unskilled workers become skilled. As a result, the wage gap reduces, yielding an inverted-U shaped pattern for the relationship between FDI and wage inequality. On the other hand, results for developed countries indicate that inequality seems to be negatively linked to inward FDI, but this effect diminishes as the FDI stock increases. This may suggest that developed countries are already at high levels of technological development and use mature technology. Thus, further inflow of technology through FDI implies that technologies become more widespread and easier to use, so that more workers can reap the benefits in terms of increased wage premium.

2.2.3 Inward foreign direct investment and skill upgrading in developing countries

Slaughter (2002) examines the relationship between inward FDI and skill upgrading in developing countries (Brazil, India, Malaysia, Mexico, and the Philippines). Focussing on the presence of U.S. multinationals, the author shows that inward FDI is positively correlated with skill upgrading in developing countries. FDI directly increases the demand for skilled labour by stimulating new investments in physical capital for adopting existing technologies. In addition, as the foreign technological knowledge spills over to domestic firms, they also increase their demand for skilled labour.

2.2.4 International economic activities and skilled labour demand: evidence from Brazil and China

Fajnzylber and Fernandes (2009) investigate the impact of three international economic activities – the use of imported inputs, exports, and FDI – on skilled labour demand of manufacturing firms in Brazil and China. The premise of their study is that the effect of these activities on firms’ demand for skilled labour in developing countries depends on the importance of technology diffusion relative to specialization based on comparative advantage. The authors find that FDI has a positive and significant effect on skilled labour demand in Brazil, implying that FDI might be diffusing skilled-biased technologies. On the other hand, FDI does not significantly affect the demand for skilled labour in China, suggesting that the effect of specialization (according to the country’s comparative advantage) in unskilled labour-intensive production by foreign-owned firms counteracts the impact of skilled-biased technology diffusion.

2.2.5 Foreign direct investment and skilled labour: evidence from Mexico

Feenstra and Hanson (1997) and Harrison and Hanson (1999) examine the effect of inward FDI on the demand for skills in Mexico. The Feenstra and Hanson study, using regional data at the industry level in manufacturing, reports that the Mexican states and industries that received more FDI after trade and FDI liberalization exhibit a greater demand for skilled labour. The other study, by Harrison and Hanson, also finds that Mexican firms that are foreign-owned tend to employ a higher share of skilled workers.

2.2.6 Impact of FDI on relative returns to skills: China

Unlike most existing studies, Wu (2001) investigates what happens when FDI is labour biased as opposed to skill biased. By studying China, a relatively labour abundant country, the author shows that such FDI will not increase the relative demand for skilled labour and will even reduce income inequality. Thus, countries like China attract FDI that takes advantage of cheap unskilled labour. This type of FDI usually brings relatively labour-biased technology transfers that employ more unskilled workers. On the other hand, FDI that is skill biased induces technology transfer and increases the relative returns to skills. Another Chinese study, by Hale and Long (2011), investigates the effect of FDI on wages. Using a stratified random sample of establishments, their results indicate that an FDI presence hires more skilled workers. By increasing the demand for skilled workers, FDI raises their wages. As such, an FDI presence increases income inequality in China.

2.2.7 Foreign direct investment and wage inequality: Thailand

Tomohara and Yokota (2011) examine the link between inward FDI and wage inequality between skilled and unskilled labour in Thailand. Using establishment-level panel data, they investigate the impact of inward FDI on relative demand shift towards skilled labour, by controlling for the effects of factors such as export orientation, establishment heterogeneity, and technological externalities. In looking at the FDI originated from Japan, Taiwan, the U.S. and other countries, they find that on average, inward FDI increases the demand for skilled labour via skill-biased technical change as well as externalities. However, FDI from Japan and Taiwan increases the demand for unskilled labour more than the demand for skilled labour as they were motivated by inexpensive factor inputs. As a result, they argue that the effects of FDI can be attributed not only to host country characteristics but also to the motivations for FDI. In another Thailand study, Matsuoka (2001) found evidence that suggests foreign-owned firms offer a higher salary to non-production employees (i.e., higher skilled workers) than to production workers. Using plant-level data on manufacturing firms, Matsuoka did not find any significant difference in labour productivity between foreign and local firms, suggesting that the wage differential might be attributed to imperfections in the labour market. Therefore, differentials in wage levels are due more to the relative bargaining strengths of skilled workers rather than the increased demand for skilled labour.

2.2.8 Foreign direct investment: who gains?

Velde and Morrissey (2002) examine whether FDI reduces poverty in developing countries. Using data from both five East Asian economies (Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines) and five African countries (Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Zambia, and Zimbabwe), they find that inward FDI increases wages. Nonetheless, wages for skilled workers increase relatively more than for unskilled workers, therefore increasing wage inequality. In another study, Velde and Morriseey (2004), using data from the International Labour Organization on wages and employment by occupation, investigate the effects of FDI on wages and wage inequality in five East Asian countries (Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines and Thailand). They find that inward FDI raises wages in these countries regardless of the level of skills. In addition, they find that FDI substantially raises wage inequality in Thailand, implying that FDI increases (reduces) the demand for skilled (unskilled) workers.

2.2.9 Globalization, increased FDI flows and wage inequality: Trinidad and Tobago

Hosein and Tewaire (2005) investigate the impact of FDI on wage inequality in Trinidad and Tobago, a small petroleum rich economy. They find that FDI increases the demand for skills and hence raises the returns to skilled labour relative to unskilled labour, with an overall consequence of an increase in sectoral wages in the FDI predominant sectors.

To sum up, it seems that while the reviewed Chinese studies often report that the country’s inward foreign investment was conducive to relative unskilled-labour employment, the evidence for most other developing and transition countries tends to suggest that foreign investment into the country induced skill upgrading (i.e., higher employment of skilled labour).

3 Empirical framework, data description and empirical results

3.1 Empirical framework

To investigate the impact of foreign-affiliate presence (or inward foreign investment) on the relative demand for skilled labour in host countries, we follow the commonly applied approach of Berman et al. (1994). The derivation of the empirical model starts out from a translog cost function, where skilled and unskilled labour are variable factors and physical capital is treated as a quasi-fixed factor. For each industry, the cost minimization assumption yields the following equation for the relative skilled labour demand:

where SW is the skilled-labour share of the total wage bill, w s (w u ) the wage paid to skilled (unskilled) workers, K capital stock, Y real value-added output, T a technology measure, i industry, t time and ε is an error term.Footnote 2

Following the literature, one can also use the employment (or hours worked) share of skilled labour (SH) as the dependent variable. An increase in SW or SH indicates skill upgrading.

The relative wage regressor ln(w s /w u ) accounts for variation in SW (or SH) due to substitution away from a more expensive factor. The coefficient β 1 is positive (negative), depending on whether the average elasticity of substitution between skilled and unskilled labour is below (above) 1.

The capital-to-value added regressor ln(K/Y) accounts for variation in SW (or SH) due to capital investment. A positive coefficient (β 2) indicates capital-skill complementarity whereby investment stimulates skilled-labour demand. The output (value added) regressor controls for industry scale and β 3 > 0 indicates the presence of increasing returns to scale. As a proxy for the technology measure (T), we use the share of ICT capital in total capital stock. If technological change shifts labour demand in favour of better-educated workers, β 4 is positive.

Equation (1) can be expanded to consider other potential explanatory variables, which according to the literature might exert some effects on the skill upgrading. Thus, we add to Eq. (1) regressors such as an offshoring variable (Offsh it ) and alternative measures of foreign-affiliate presence or inward foreign investment (IFI it ).

The intuition behind the offshoring variable (Offsh) runs as follows. In these days of international economic integration, a firm (or an industry) may decide to source certain activities that require low skills or standard technologies to external providers that have cheaper or more efficient production capabilities. This possibility of offshoring/outsourcing might allow the firm to move up the value chain by focusing on high value-added activities (i.e., those that are higher technology- and/or knowledge-intensive) and thereby increase the demand for skilled labour.

The key question in Eq. (2) is the sign of β 6. The interpretation of a significantly positive (negative) estimate of β 6 is that increased inward foreign investment has contributed to shifts in demand towards skilled (unskilled) workers.

However, identifying the effect of the relative wage term on skilled labour demand in Eq. (2) is difficult, since it is not plausible to treat relative wages as exogenous. In fact, several studies on the skill upgrading have noted that the relative wage term is likely to be endogenous in a wage share equation, and therefore omitted this variable in their estimation – as instruments to correct for its endogeneity are not available – see, e.g., Berman et al. (1994), Blonigen and Slaughter (2001), Fajnzylber and Fernandes (2009), Tomohara and Yokota (2011), Bernard and Jensen (1997), Pacnik (2003). As suggested, e.g., in Berman et al. (1994), although part of the variation in the relative wage can be due to differences in the skill-mix across industries, some of it is likely to be caused by the skill upgrading occurring within industries.Footnote 3 Furthermore, the definitional relationship between the dependent variable (as measured by the share of skilled labour in total wage bill) and the wage measures (constructed as the wage bill divided by employment for each skill group) might introduce bias into the estimates. To avoid this problem, the relative wage is usually excluded from the estimation.

Thus, following most previous studies, we also drop the relative wage term, but we include industry dummy variables that control for some differences in the excluded term and for other systematic differences in skilled labour demand across industries. The actual estimating equation therefore becomes:

where μ i represent industry-fixed effects Footnote 4

3.2 Data description and empirical results

The study covers 43 Canadian industries, including primary, manufacturing and services, over the period 1999-2008Footnote 5 – see Table 1 for the list of industries. The data on hours worked and labour compensation by educational attainment (primary or secondary education, post-secondary education, and university degrees or above), nominal GDP, GDP deflator, and cost of ICT and total capital services are obtained from Statistics Canada KLEMS database. Following the literature, we define skilled labour as employees with at least a post-secondary education. The total and M&E capital stock are geometric (infinite) end-year net stock of fixed non-residential capital in chained (2002) dollars, obtained from Statistics Canada CANSIM table 031–0002.

Data on foreign ownership, measured by the total assets and operating revenue under foreign control (i.e., involving a majority of at least 50 % of the voting equity), are obtained from Statistics Canada (Corporations Returns Act) by a special request. Total assets are the sum total of economic resources over which an enterprise exercises certain control. They include cash and deposits; accounts receivable and accrued revenue; inventories; investments and accounts with parents, subsidiaries and affiliates; portfolio investments; loans given to other enterprises; and capital assets. Operating revenue includes revenues from the sales of goods and services; rental and operating lease revenues; and revenues from commissions, franchise fees, and royalties. While the asset-based measures of foreign control are a stock item (reflecting economic decisions and market conditions that evolve more slowly over time), the revenue-based measures represent a flow item and are closely tied to the business cycle. Revenues tend to reflect current business conditions, causing them to be more volatile than asset-based measures. On the other hand, the stock of inward FDI, which involves a foreign investor holding at least 10 % of a local firm’s voting equity, includes the cross border investment between companies in the form of equity and inter-company debt; this data is obtained from CANSIM Table 376–0052. Thus, it is noteworthy that foreign ownership involves FDI but not necessarily the other way around.

Offshoring is defined as the imported share of intermediate inputs, calculated with the import proportionality assumption (which is often employed by the OECD) using input–output (IO) tables.Footnote 6

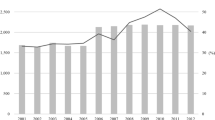

Before moving to the econometric analysis, Fig. 1 presents the trend development in the skilled-labour shares of total employment (i.e. hours worked) and wages, as well as in the shares of total assets and operating revenue under foreign control across specific industries.

Skilled-labour shares of hours worked & wages and Share of assets & operating revenue under foreign control, 1999–2008. Notes: Skilled labour refers to employees with at least a post-secondary education; and data for foreign-controlled affiliates’ assets and operating revenue include only enterprises with foreign ownership of 50 % or more

In the manufacturing sector, the relative employment and wages of skilled labour move in the same direction. More precisely, the shares of skilled labour in total hours worked and wages rose from 52.7 and 59.1 % in 1999 to 60.9 and 66.9 % in 2008, respectively. Over the same period, foreign-affiliate shares of total assets and operating revenue increased from 46.0 and 51.8 % in 1999 to 56.4 and 53.4 % in 2008, respectively. Together, these parallel trends suggest that a rising foreign-affiliate presence may have contributed to skill upgrading and rising wage inequality. Similar trend developments in the skilled labour shares of hours worked and wages, as well as in the shares of foreign-affiliate assets and revenue are observed in both wholesale and retail trade, although the magnitude of increases are lower in the latter industry. As for the primary sector, it has also experienced skill upgrading and rising wage share of skilled workers; but the extent of foreign ownership over the total assets and revenue has somewhat declined. For the variables discussed above and other key variables, Table 2 presents the summary statistics.

Turning to the econometric analysis, we estimate Eq. (3) using the feasible generalized least squares (GLS) technique to correct for arbitrary heteroscedasticity and serial correlation between the error terms for a given cross-section. This specification involves covariance across time periods within a given cross-section, as in a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) framework with period-specific equations, and is termed ‘period SUR’. Computationally, the cross-sectional fixed effects cannot be used together with period SUR. Thus, we follow Rao et al. (2008) in grouping industries with similar characteristics and using group dummies to control for the effect of differences in inter-group characteristics. All industries are reclassified into nine groups, with one dummy variable for each group. The nine groups are primary (NAICS 11–213), construction (NAICS 23), resource-based manufacturing (NAICS 311, 312, 321, 322, 324, 326–332), labour-intensive manufacturing (NAICS 313–316, 337, 339), high-tech manufacturing (NAICS 323, 325, 333–336), trade (NAICS 41–45), utility and transportation (NAICS 22, 484, 485), information, finance, insurance, real estate and business services (NAICS 51–562), and other non-public services (NAICS 61–81). The group dummy (D i j ) equals one if i ∈ j and zero otherwise.

We first carry out the estimation using the sample across all industries – see Table 3 for the results. Table 3 shows the results from estimating Eq. (3) with the demand for skills (the dependent variable) measured by both the employment and wage bill shares of skilled labour. It emerges that a foreign-affiliate presence, measured either by foreign majority ownership (i.e., total assets or revenue under foreign control) or FDI, has a positive and significant effect on the relative demand for skilled labour. Further, the magnitudes of the estimated coefficients on the three foreign investment variables are similar across the equations for employment and wage bill shares of skilled labour.Footnote 7

As for the impacts of other variables included in Eq. (3), we find that offshoring activity has no statistically significant impact on skill upgrading, which is counterintuitive – and this result is robust to considering offshoring as the only explanatory variable. Nonetheless, some existing studies also reported a similar finding (see, e.g., Esposito and Stehrer 2009). The technology measure variable, proxied by the share of ICT capital, induces higher skilled labour demand, confirming the skill-biased technological change. The coefficient on the value-added is positive and significant, indicating increasing returns to scale. Finally, the coefficient on the M&E capital to value-added ratio indicates a complementarity between M&E capital and skilled labour.Footnote 8

Ideally, it would be appealing to run regression for each industry separately, but unfortunately the number of observations in this case (i.e., the temporal dimension of the panel data) does not permit a meaningful industry-specific analysis. Nonetheless, according to the OECD study by Koyama and Golub (2006), there exist higher regulatory restrictions on FDI into Canadian services industries. As a result, we split the sample into services and non-services sectors (as shown in Table 1) and investigate whether inward foreign investment induces differential impact on skill upgrading across the two sectors – these results are reported in Table 4.Footnote 9 It seems that notwithstanding higher regulatory FDI restrictions in services industries, foreign-affiliate presence has had a similar (marginal) impact on skill upgrading across both the services and non-services sectors. Splitting the industries in this way, it also appears that offshoring activity contributes to skill upgrading in the services sector, which is consistent with services industries doing relatively more offshoring. For the other variables, all previous findings almost hold. See Table 5 for the extent of FDI regulatory restrictiveness by country and sector.

4 Conclusions

It is often argued that MNEs are important transmitters of technologies internationally, as they profit from their superior technological knowledge in many countries. By transferring advanced technologies and managerial know-how abroad, foreign affiliates of MNEs or foreign investments affect technological change in host countries. Consequently, as technological change is often skills biased, an increase in foreign investments might have a positive impact on the relative demand for skilled labour in the recipient countries. After conducting an extensive review of the empirical evidence on this issue across many countries, this paper found that the result tends to be country-specific and that there is no previous study that explored this issue in Canada. Thus, the present paper contributed to the literature by filling this important knowledge gap in investigating whether a foreign-affiliate presence contributed to the relative employment of skilled individuals in Canada.

The results of the paper sum up as follows. First, most Canadian industries have experienced skill upgrading, and inward foreign investment, as measured by FDI or majority ownership, has contributed to this development. This finding accords with the fact that in Canada, foreign majority-owned firms account for about 85 % of the country’s inward FDI stock. Second, notwithstanding higher regulatory restrictions on foreign investment into Canadian services industries, foreign investment has had a similar impact on skill upgrading across both the services and non-services sectors. Finally, offshoring is found to only have a positive significant impact on skill upgrading in the services sector.

While our empirical analysis is specific to Canada, one could draw a general conclusion (based on our findings and the review of the existing empirical evidence) that foreign investment contributes to jobs creation in the recipient countries. However, knowing which skill group is most likely to benefit from these employment opportunities would depend on the motives and the types of inward FDI.

Notes

A transnational investment is typically classified as direct investment if a foreign investor holds at least 10 % of a local firm’s voting equity; and a foreign affiliate is a business in which there is FDI. As for a foreign-controlled/owned firm, it entails the ownership of a majority (50 % or more) of the voting equity in a firm. An MNE is a company that owns and controls firms in at least two countries. Thus, it is noteworthy that foreign ownership involves FDI but not necessarily the other way around. In practice, however, a large proportion of FDI involves majority-owned firms. For instance, Statistics Canada reports that majority-owned firms accounted for about 85 % of Canada’s inward FDI stock in 2005. In this paper, we use the terms FDI and foreign affiliates of MNEs interchangeably.

See Fajnzylber and Fernandes (2009, p.566) for the derivation steps. Nonetheless, this empirical specification is common in the literature and its variants have been used by, e.g., Bandick and Hansson (2009), Tomohara and Yokota (2011), Blonigen and Slaughter (2001), Taylor and Driffield (2005), Feenstra and Hanson (1997) and others.

Also, as mentioned in Fajnzylber and Fernandes (2009), the cross-sectional variation in observed relative wages is often due to a variation in the unobserved quality of labour and thus is not exogenous.

Arguably, this treatment of relative wages is a shortcoming of the cost based approach to skill upgrading. One referee noted that the exclusion of this variable presumably reflects a trade-off between potential biases from omitted variables and from endogeneity. However, although not reported here, as a specification check, we also accounted for the relative wages and estimated equation (3) with the skilled-labour share of total employment as the dependent variable. This approach yielded the same conclusions.

It is worth mentioning that some authors, such as Berman et al. (1994) and Blonigen and Slaughter (2001), have estimated variants of Eq. (3) in first differences. Given the short temporal dimension of our panel data and for the sake of more degrees of freedom, we here estimate in level. Nonetheless, we ensure through diagnostic tests that the specification is not spurious.

As only the imported share of total domestic use of each commodity can be derived from IO tables, we simply assume that for each commodity the imported share in intermediate use is the same as the imported share in final demand – this is the import proportionality assumption.

For each equation, we considered separately a single foreign investment variable to avoid a potential multicollinearity problem.

However, the coefficient on M&E capital to value-added ratio is positive but statistically insignificant when the foreign-affiliate presence is measured by FDI intensity. This likely results from the collinearity between the two variables as both are normalized using the value-added.

In Table 4, the FDI intensity variable is overlooked because the period-SUR GLS estimation method we used requires that the number of cross-sections must equal or exceed the number of periods, which is not the case for the services sector when this variable is considered.

References

Almeida R (2007) The labor market effects of foreign owned firms. J Int Econ 72:75–96

Bandick R, Hansson P (2009) Inward FDI and demand for skills in manufacturing firms in Sweden. Rev World Econ 145:111–131

Berman E, Bound J, Grilliches Z (1994) Changes in the demand for skilled labor within U.S. manufacturing: evidence from the annual survey of manufactures. Q J Econ 109:367–397

Bernard AB, Jensen JB (1997) Exports, skill upgrading, and the wage gap. J Int Econ 42:3–31

Blonigen BA, Slaughter MJ (2001) Foreign-affiliate activity and U.S. skill upgrading. Rev Econ Stat 83(2):362–376

Crino R (2005) Wages, skills, and integration in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic: an industry-level analysis. Transit Stud Rev 12(3):432–459

Driffield N, Taylor K (2000) FDI and the labour market: a review of the evidence and policy implications. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 16(3):90–103

Driffield, N. and K. Taylor (2002) “Spillovers from FDI and skill structures of host-country firms”, Discussion Papers in Economics

Esposito, P. and R. Stehrer (2009), “Effects of High-Tech Capital, FDI and Outsourcing on Demand for Skills in West and East”, the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, wiiw Working Papers, No. 51

Fajnzylber P, Fernandes MA (2009) International economic activities and skilled labour demand: evidence from Brazil and China. Appl Econ 41:563–577

Feenstra R, Hanson G (1997) Foreign direct investment and relative wages: evidence from Mexico’s maquiladoras. J Int Econ 42:371–393

Figini P, Gorg H (1999) Multinational companies and wage inequality in the host country: the case of Ireland. Weltwirtschaftliches Arch 135(4):594–612

Figini P, Gorg H (2011) Does foreign direct investment affect wage inequality? An empirical investigation. World Econ 34:1455–1475

Grasseni, M. (2004) “Technology, MNEs Activity and Italian Skill Upgrading”, Departmental Working Papers No. 25, Department of Economics, Management and Quantitative Methods at Università degli Studi di Milano

Hale G, Long C (2011) “Did foreign direct investment put an upward pressure on wages in China?”, IMF economic review. Palgrave Macmillan 59(3):404–430

Harrison A, Hanson G (1999) Who gains from trade reform? Some remaining puzzles. J Dev Econ 59:125–54

Hosein R, Tewarie B (2005) Globalization, increased FDI flows and wage inequality in a small petroleum rich economy. West Indian J Eng 27(2):1–24

Huttunen K (2007) The effect of foreign acquisition on employment and wages: evidence from finnish establishments. Rev Econ Stat 89(3):497–509

Koyama, T. and S. S. Golub (2006), “OECD’s FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index: Revision and Extension to more Economies”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 525, OECD Publishing

Matsuoka, A. (2001) “Wage Differentials among Local Plants and Foreign Multinationals by Foreign Ownership Share and Nationality in Thai Manufacturing”, ICSEAD working paper series 2001–25

Nakamura, M. (2008) “Foreign and Domestic Equity Relationships and Firms’ Internal Wages: Differential Impacts by Worker Ranks at Japanese Manufacturing Firms”, mimeo, Sauder School of Business, University of British Columbia

Pavcnik N (2003) What explains skill upgrading in less developed countries? J Dev Econ 71:311–28

Piva M, Vivarelli M (2004) The determinants of the skill bias in Italy: R&D, organisation or globalisation? Econ Innov New Technol 13(4):329–347

Rao S, Tang J, Wang W (2008) What explains the Canada-US labour productivity gap? Can Public Policy 34:163–92

Slaughter, M. (2002) “Does Inward Foreign Direct Investment Contribute to Skill Upgrading in Developing Countries?”, CEPA Working Paper 2002–08, New School University

Tavares, A.T. and A. C. Teixeira (2005) “Human Capital Intensity in Technology-Based Firms Located in Portugal: Do Foreign Multinationals Make a Difference?”, FEP Working Papers No. 187, Universidade do Porto, Faculdade de Economia do Porto

Taylor K, Driffiled N (2005) Wage inequality and the role of multinationals: evidence from UK panel data. Lab Econ 12:223–249

te Velde DW, Morrissey O (2004) Foreign direct investment, Skills and wage inequality in East Asia. J Asia Pac Econ 9(3):348–369

Tomohara A, Yokota K (2011) Foreign direct investment and wage inequality: is skill upgrading the culprit? Appl Econ Lett 18(8):773–781

Velde, D.W. te and O. Morrissey (2002) “Foreign Direct Investment: Who Gains?”, Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Briefing Paper

Wu X (2001) Impact of FDI on relative return to Skill. Econ Transit 9(3):695–715

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two anonymous referees, Mahamat Hamit‐Haggar, Michael‐John Almon, Someshwar Rao, and seminar participants at Industry Canada for their valuable comments and suggestions. All errors and omissions remain the responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Industry Canada, Canada Revenue Agency or the Government of Canada.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Souare, M., Zhou, B. Foreign-affiliate presence and skilled labour demand. Int Econ Econ Policy 13, 233–254 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0302-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0302-y