Abstract

With the increasingly adverse impact of global warming on extreme weather conditions, including landslides, it is more important than ever to alert the public to landslide risks so that people can take precautionary measures. We report the first major project in Hong Kong assessing the public’s understanding of landslides and perceptions of the Landslip Early Warning System (“current LEWS”) and exploring the perceived usefulness of the concept of a multi-tiered LEWS (“multi-tiered LEWS”). In Study 1, we gauged the public’s understanding of landslides and knowledge of the current LEWS by collecting information from five focus groups. That information was used to construct the survey that we administered in Study 2, in which 1834 individuals participated in face-to-face interviews. The results show that only 37% of the participants saw the connection between global warming and landslides. The majority of the sample believed that slope safety has clearly improved over the last decade (88%) and that landslides are a remote concern (91%). Although 90% of the participants were aware of the current LEWS, only 28% were concerned about it because it had little impact on their residential or activity areas. The concept of a multi-tiered LEWS was positively received, although there is an urgent need for further research to demonstrate how to implement this concept with sufficient public education to ensure that it will improve public alertness of landslides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hong Kong, which is home to 7.6 million residents, occupies a land area of 1100 km2 populated by hilly slopes with little flat land (60% of the land is steeper than 15°, 30% is steeper than 30°). Urban development has also resulted in the creation of more than 60,000 large engineered slopes (Cheung 2021). The combination of highly concentrated urban developments on steep terrain near engineered slopes and natural hillsides results in a worryingly high risk of landslides. Worldwide, landslides pose a serious risk of death, causing more than 55,000 fatalities from 2004 to 2016 (Froude and Petley 2018). Hong Kong records an average of 300 (reported) landslides per year, resulting in significant socioeconomic damages (CEDD 2014) and nearly 500 deaths since 1948 (Cheung 2021; Keegan 2022). At the global level, special journal issues and annual forums on technological advances in detecting landslide risks provide a platform for joint efforts to address the problem of landslides (see Fifth World Landslide Forum 2021 for conference topics; Sassa 2017; Sassa and Picarelli 2010). Unfortunately, concerted efforts in the field of engineering are not paralleled by research efforts that provide an understanding of the public’s perception of landslide risks and warnings. Our study focused on gauging the public’s perception of Hong Kong’s Landslip Early Warning System (“current LEWS”), which is the world’s first territory-wide landslide warning system.

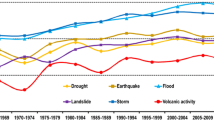

The World Economic Forum’s (2022) most recent report about the top 10 global concerns identifies five risks related to environmental issues, including extreme weather, highlighting global concerns about management and safety measures to respond to climate change. According to the Hong Kong Observatory (HKO), Hong Kong’s annual rainfall progressively increased at an average rate of 36 mm per decade from 1947 to 2019, possibly because of climate change (Cheung 2021). Indeed, the HKO reported that the chance of hourly rainfall of at least 100 mm has doubled over the past century (Wong et al. 2011). Situated in a subtropical region, Hong Kong receives an average annual rainfall of 2400 mm that certainly fuels landslides. With the effects of global warming causing severe rainstorms, the frequency and scale of landslides are expected to increase correspondingly (Gariano and Guzzetti 2016), underscoring the precipitating dangers of extreme landslide events and the need for enhanced foresight.

The 2008 rainstorm over Hong Kong’s Lantau Island brought more than 600 mm of rain in a 24-h period, causing more than 2400 landslides (see the CEDD for risk descriptions at https://hkss.cedd.gov.hk). A simulated study transposed this rainstorm to Hong Kong’s main districts, resulting in more than 1900 natural-terrain landslides and 100 engineered slope failures (Ho et al. 2016). In another simulated study, Taiwan’s 2009 Typhoon Morakot was transposed to Hong Kong, resulting in the possibility of 1040 mm of rainfall in 24 hours and 49,000 natural-terrain landslides, which would have completely overwhelmed the Hong Kong landslide management system (Ho et al. 2016). With escalating concern about the role of global warming in more extreme landslide events, there is an outcry for an effective warning system that will alert the public to prepare for landslides. We sought to evaluate the perceived effectiveness of Hong Kong’s current LEWS’s capability in alerting and urging people to action during landslide emergencies, a system that has been in use for 45 years.

In response to increasing concerns about landslide risks in the 1970s, Hong Kong created a regulatory body to oversee slope maintenance and landslide prevention. Established in 1977, the Geotechnical Engineering Office (GEO) developed the Slope Safety System with the goal of reducing the risk of landslides in Hong Kong and promoting public awareness of landslides and their associated risks. 1977 was also the year that Hong Kong established the first iteration of the LEWS, the first in the world to cover an entire territory (Chan et al. 2003), whereas the landslide public warning alert was made public in 1983 (Kong et al. 2020). The current LEWS was developed using real-time rainfall data collected from a territory-wide network of automatic rain gauges, rainfall forecasts provided by meteorologists, and a rainfall-landslide correlation model (Yu et al. 2004). When the current LEWS detects emerging landslide risks, two of the three tiers (i.e., levels) of its warning system are activated to ensure the interdepartmental preparedness of the HKO and the GEO. The first (internal) alert level (the “Consultation” level) is triggered when the past 24 hours of rainfall at 10 or more rain gauges exceeds 100 mm. The second (internal) alert level (“Alert” level) is triggered when the total rainfall required to reach the final public alert level (“Warning” level) is just short of 100 mm (Guzzetti et al. 2020; Kong et al. 2020). The current LEWS only alerts the public when its highest tier (“Warning” level) is reached indicating that at least 15 landslides are forecasted in Hong Kong, warning the entire city to exercise caution and avoid risky areas.Footnote 1 Historically, a warning was in force for 90% of Hong Kong’s fatal landslide incidents (Kong et al. 2020). The GEO also developed a Landslide Potential Index featuring a multi-tiered system categorized by the estimated number of landslides based on rainfall information (see the CEDD for risk descriptions at https://hkss.cedd.gov.hk). However, this index is only shared with the public after every intense rainstorm.

Around the globe, multi-tiered public alert systems (see Guzzetti et al. 2020) provide ordered levels of guidance to residents in affected areas, a feature that the current LEWS lacks (see Table 1 for a comparison of various alert systems). For instance, in 2004 Taiwan established a three-tiered landslide warning system that has two public advisory levels: “Yellow” (to advise evacuation from at-risk areas) and “Red” (forced evacuation). In 2008, Seattle (WA, USA) established a four-tiered warning system that has three public advisory levels (“Outlook,” “Watch,” and “Warning”), which are associated with increasing degrees of caution (Baum and Godt 2010). In the same year, the Åknes mountain region in Norway implemented a five-tiered landslide warning system with three public advisory levels alerting and urging preparations for clustered evacuation. It advises local municipal departments to increase their preparedness days in advance of landslide risks associated with the mountain (Blikra et al. 2007; Lacasse and Nadim 2009; see also Calvello et al. 2015 for a similar system with a public advisory in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). In a global survey administered to institutions overseeing site-specific LEWS, 14 out of 23 institutions (60%) reported utilizing several levels of alarms, which can provide additional levels of advice for emergency actions from the public (Michoud et al. 2013). These graded alerts enable communication with the public about increasing landslide dangers and the corresponding precautionary measures. In this research, we tested the public’s perception of the concept of a multi-tiered LEWS in Hong Kong. In Fig. 1, we compare the current warning system in Hong Kong with the concept of the multi-tiered warning system.

With hazardous landslide incidents a distant memory for many Hong Kong residents (the most recent “Extremely High” landslide cases, as defined by the Landslide Potential Index, occurred in 1994 and 2008), there are concerns surrounding the continued effectiveness of the current LEWS to achieve its intended purpose of urging residents to reduce their exposure to landslide risks. Since 1994, the single public alert has been issued an average of three times a year and has been used during minor to major landslide incidents, resulting in potential perceptions of false positive events on the part of many Hong Kong residents in areas that were unaffected by landslides (see the HKO website for annual landslide warning data at https://www.hko.gov.hk). Extensive research into and expansion of the current LEWS has focused on utilizing technological advancements that target enhanced landslide predictive modeling and real-time data collection, resulting in improved internal warning levels (see Choi and Cheung 2013; Kong et al. 2020; Pun et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2004; see also Sassa and Picarelli 2010). However, these technological advances were not paralleled by sufficient research into whether the single public alert has effectively guided residents to timely precautionary actions since its original iteration in the 1980s.

Using interviews and questionnaires, Scolobig (2016) explored the perception of landslide risk governance in the Nocera Inferiore region in Italy and found that although residents understood the dangers of landslides in their areas, they were less aware of policies on risk prevention or government-implemented emergency plans. The author concluded that to enhance these policies’ effectiveness, the government should work closely with the residents in identifying methods of communicating the risks to the public, thus ensuring public safety in natural disasters. These suggestions were echoed by the European Directives and UNISDR Frameworks that encourage active participation by the public in landslide preparedness policies (see also Scolobig et al. 2016). Following the footsteps of Scolobig and colleagues’ research agenda, we utilized semi-structured interviews and questionnaires to gauge the public’s understanding of the current LEWS and the concept of the multi-tiered LEWS for use in Hong Kong, thereby enabling stakeholders or end users to take part in evaluating policy effectiveness.

We report two studies to understand the effectiveness of the LEWS in Hong Kong. In Study 1, we employed a qualitative methodology and conducted five focus groups with residents living in landslide-prone areas to gauge their overall perceptions of landslide risks. Common themes in the focus groups were identified and used to develop questions for use in Study 2’s quantitative face-to-face interviews with nearly 2000 participants. The face-to-face interviews enabled us to gauge the public’s perception of landslide awareness, along with their attitude toward the concept of a three-tiered LEWS. Figure 2 presents a flow chart of the entire data collection process.

Study 1: focus groups

Sample

Study 1, which took place in December 2019, involved five focus groups with 5 to 11 participants each. The focus groups included 34 residents living in landslide-prone areas and five media representatives. With the help of non-governmental organizations located in landslide-prone areas, we used a nonprobability sampling technique to identify the residential participants in each area by advertising the study and inviting residents to participate. The media representatives were recruited by the GEO based on their previous collaborations. All focus groups took place at either the GEO or the offices of non-governmental organizations. The sample was 28% men and 72% women, all of whom were at least 21 years of age. The general characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 2.

Method

The focus group discussion questions were designed to assess three key topics (see Table 3):

-

A

Understanding of landslide issues in Hong Kong

-

B

Perceptions of the current LEWS

-

C

Reception of the concept of a multi-tiered LEWS

All of the discussions were conducted in Cantonese by an experienced moderator, who had 30 years of experience of conducting focus group research with participants from various age groups and socioeconomic backgrounds in the Greater China region. The discussions were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Based on the results of the focus groups, common themes were identified and used to develop the survey questions and response options for Study 2. Upon completion of the discussion, the participants were debriefed and thanked. Each of the residents received a HK$400 (US$50) cash incentive for his/her time.

Results

Based on the qualitative data collected from the focus groups, we identified common themes and ideas for each of the three key topics discussed.

Landslide issues in Hong Kong

Because all of the participants lived in landslide-prone areas, we started the focus group discussion by addressing landslide issues. The results were interesting. Almost none of the residential participants had ever experienced a landslide, and some did not believe that their residential area was at risk. For instance, one resident stated that her husband and she “have lived there for 40 years, and [they] had never experienced any landslides.” The few residential participants who had experienced landslides described them as “scary” and reported that they “happened 10–20 years ago.” However, some participants did not express concern, believing that landslides were “location-specific” and “would not occur in their areas.” Some participants were also aware of the GEO’s slope safety work in the last decade and said that it had helped improve slope safety. They also believed that currently, Hong Kong’s slopes are generally safe.

The current (single-tiered) LEWS

To assess the participants’ perceptions of the current LEWS, we asked whether they had seen, heard, and/or paid attention to it. Some stated that they were aware of the current LEWS, but they did not express concern about it or pay attention to it. These participants indicated that the system “does not convey much information” and “is not that useful.” Some also reported that the current LEWS did not provide a clear action plan and therefore was not as salient as other weather warnings (e.g., warnings about rainstorms and tropical cyclones), which did provide such information. They also felt that the current LEWS failed to communicate important information about the severity, risk levels, and locations of landslides. Some noted that this lack of information resulted in the perception that landslides would not occur in their residential area.

The concept of a multi-tiered LEWS

To understand the participants’ reception of a multi-tiered LEWS, we showed them the idea of a three-tiered system, which would warn the public when each level (i.e., tier) of landslide risk was attained, and asked whether they understood it. Some reported that although the system was easy to comprehend, it could be further improved if “specific precautionary measures were also provided for each tier.” Some of the participants proposed their own precautionary measures for each tier (see Table 4 for sample measures translated into English). The participants also expected location-specific information and indicated that “the same warning level may not apply to all areas.” Some also suggested the potential need to educate the public on how to interpret the multi-tiered LEWS if a warning is issued at the same time as other weather warnings. For instance, if the (current) Black Rainstorm and the (hypothesized) Level 1 Yellow Landslip Warning are issued, should people stay at home or go to a shelter?

When discussing the perceived usefulness of a multi-tiered LEWS, the participants identified the following four attributes:

-

A

Communication (communicating the risk of landslides to the public)

-

B

Alertness (raising public awareness of the risk of landslides)

-

C

Call to action (reminding the public to take precautionary measures)

-

D

Crisis management (reducing landslide-related casualties)

Some of the participants expressed the view that the new system “conveys a stronger sense of crisis,” “increases people’s alertness,” and signals to people that they “may have to leave.” In other words, they found the three-tiered warning system to be more effective than the current system on all four of the perceived usefulness attributes.

Study 2: face-to-face survey interviews

Sample

Study 2 involved face-to-face survey interviews conducted in October and November 2020. The sample consisted of 1834 individuals recruited from all 18 districts in Hong Kong. In each district, experienced interviewers from a local professional fieldwork service provider used a systematic sampling technique in which they invited pedestrians in various high-traffic locations (e.g., subway stations, shopping malls) to complete a survey interview on a tablet. We conducted the interviews between 10 a.m. and 9 p.m. on both weekdays and weekends to increase the likelihood of recruiting participants from different socioeconomic backgrounds (e.g., students, working-class, retired seniors). The survey was written in traditional Chinese and the interviews were conducted in Cantonese.Footnote 2 The average completion time was 15 min. The sample was 45% men and 55% women, all of whom were at least 18 years of age. The sample’s general characteristics are shown in Table 5.

Method

Using the common themes identified in the focus group discussions in Study 1, we developed a questionnaire for Study 2 to obtain quantitative data. The survey covered the following four sections (described in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7):

-

A

Perceptions of global warming

-

B

Understanding of landslide issues in Hong Kong

-

C

Understanding and evaluation of the current LEWS

-

D

Evaluation of the concept of a multi-tiered LEWS

Both open- and closed-ended questions (e.g., yes/no categories, Likert scales, and multiple-choice questions) were used in the survey. The participants also provided demographic information such as gender and age. The survey also included other questions that were not central to our main research questions and therefore are not reported in this paper. Upon completion of the survey, each participant was debriefed, thanked, and given a souvenir.

Results

Global warming

To examine the participants’ view of the relationship between global warming and weather conditions in Hong Kong, we asked whether they thought global warming had any impact on eight weather conditions. As shown in Fig. 3, the two modal responses were “rise in temperature” (82%) and “disappearance of winter” (72%). Of special note was that “landslides” (37%) were perceived as the least related to global warming. In other words, the participants appeared to be unaware of the close link between global warming, rainfall, and landslides.

Landslide issues in Hong Kong

The responses to questions about landslide issues in Hong Kong are shown in Fig. 4. To examine the participants’ understanding of landslide issues in the city, we asked about their level of concern related to slope safety problems on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not concerned at all”) to 4 (“very concerned”). Approximately half of the participants indicated that they were either “quite concerned” (42%) or “very concerned” (8%) (B1). To examine the participants’ views on slope safety in Hong Kong, we asked about their perceptions of the safety of Hong Kong’s slopes on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not safe at all”) to 4 (“very safe”), and a majority responded that the slopes were either “quite safe” (75%) or “very safe” (9%) (B2). To examine whether the participants thought that slope safety has improved over the last decade, we asked them to compare the slope safety of today with that of 10 years ago on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“far worse than 10 years ago”) to 4 (“far better than 10 years ago”), and a majority responded that today’s slope safety was either “a bit better than 10 years ago” (53%) or “far better than 10 years ago” (35%) (B3). Taken together, although only half of the participants expressed concern about slope safety problems, the majority believed that Hong Kong’s slopes are safer than they were 10 years ago and are generally safe today.

To assess the participants’ awareness of the risk of landslides in Hong Kong, we asked them whether their residential area was at risk of landslides, and 91% answered “no” (B4). Furthermore, when asked about their previous experiences with landslides, 96% of the participants indicated that neither they nor their families had ever experienced landslides (B5). Taken together, it is important to note that most of the participants believed that they were immune to the risk of landslides in Hong Kong.

The current (single-tiered) LEWS

We also examined the participants’ awareness and knowledge of Hong Kong’s weather warnings. More importantly, we wanted to learn whether the participants were concerned about the current LEWS, which warns the public only upon the attainment of the highest level of landslide risk, and were aware of the manner in which it issues public warnings. The responses to these questions related to the current LEWS are shown in Fig. 5.

To examine their awareness of the current weather warnings, we asked the participants whether they had seen or heard of each of the ten weather warnings issued by the HKO via different media channels (e.g., television, radio, Internet). The Rainstorm Warning had the highest level of awareness (99%), whereas the Frost Warning had the lowest level of awareness (58%) (C1). Ninety percent of the participants reported having seen or heard of the Landslip Warning (nearly the same percentage as those who were aware of the Fire Danger Warning).

To assess the participants’ knowledge of the graphical representation of the Landslip Warning, we asked the 90% of the participants who were aware of the warning to recall and describe the signal. The most frequent features recalled were “mountain” (50%) and “pebbles running down” (42%), which were accurate features of the signal (C2). When shown the Landslip Warning signal, 90% of the participants reported having seen it (C3).

To measure whether the participants’ broad awareness of the ten weather warnings matched their concern about them, we compared the percentage of those who reported being aware of each warning with those who reported being concerned about each warning. The participants were the most aware of (99%) and concerned about (89%) the Rainstorm Warning (C1 and C4). Although 90% of the participants were aware of the Landslip Warning, only 28% were concerned about it. Of special interest was the difference between the two percentages (i.e., awareness versus concern) for each warning. The warning with the lowest difference was the Rainstorm Warning (10%), and the warning with the highest difference was the Landslip Warning (62%). Thus, it is prudent to conclude that the Rainstorm Warning functions well enough that the participants were aware of and paid attention to it. In contrast, although the participants were aware of the Landslip Warning, they paid little attention to it. When the 72% of participants who expressed a lack of concern about the Landslip Warning were questioned, the majority indicated that the reason for their lack of concern was that the warning does not impact their residential or work areas (65%) (C5).

The concept of a multi-tiered LEWS

The responses to questions about the proposed multi-tiered LEWS are shown in Figs. 6 to 7. To assess the participants’ evaluation of the concept of a multi-tiered LEWS that warns the public at every level of landslide risk, we showed them the LEWS and the concept of a multi-tiered public warning system and asked them which one they preferred. The majority preferred the multi-tiered system (84%) to the current LEWS (15%), with 1% indicating no preference (D1). When asked how easy it was to understand the concept of a multi-tiered system on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not easy at all”) to 4 (“very easy”), the majority responded that the multi-tiered system was either “quite easy” (65%) or “very easy” (24%) to understand (D2).

To understand the perceived effectiveness of the current LEWS and that of the concept of a multi-tiered system, we asked the participants to compare the effectiveness of the two systems with respect to the four attributes identified in Study 1:

-

A

Communication (communicating the risk of landslides to the public)

-

B

Alertness (raising public alertness to the risk of landslides)

-

C

Call to action (reminding the public to take precautionary measures)

-

D

Crisis management (reducing landslide-related casualties)

For each attribute, the participants rated the effectiveness of each system on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not effective at all”) to 4 (“very effective”). A paired sample t-test indicated that the proposed multi-tiered LEWS received significantly higher ratings on all four attributes (ts (1833) > 10.67, ps < .01) than the current LEWS, suggesting that the proposed multi-tiered LEWS excelled in communication, alertness, call to action, and crisis management (D3–10).

To assess the evaluation of the design of the concept of a multi-tiered warning signal, we asked the participants to rate the suitability of the Yellow-Red-Black code for characterizing each tier on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not suitable at all”) to 4 (“very suitable”). The majority responded either “quite suitable” (63%) or “very suitable” (28%) (D11).

To understand how the warning system could affect the participants’ precautionary measures and actions, we asked them to describe what they would do when a current LEWS warning of the highest level of landslide risk versus a multi-tiered LEWS warning of any level of landslide risk was issued. With respect to their reaction to a current LEWS warning of a high risk, the most frequent responses were “not take any measures” (38%), followed by “avoid walking to or standing close to a steep slope/retaining wall” (21%) (D12). With respect to their reaction to a multi-tiered LEWS warning, the modal response for all three levels of risk was “leave home/slope for a safe place or shelter” (47%, 56%, and 58% for Levels 1, 2, and 3, respectively) (D13–15).

Of special note were the graded responses for several precautionary action categories. The current LEWS warning attained the highest percentage (38%) of responses in the “not take any measures” category, which can be interpreted as ignoring the warning. In the same category, the percentages for Levels 1 to 3 were very low (14%, 6%, and 4% for Levels 1, 2, and 3, respectively). The current LEWS warning attracted 16% of the responses in the “leave home/slope for a safe place or shelter” category, whereas a Level 1 multi-tiered LEWS warning would prompt 47% to leave, a Level 2 multi-tiered LEWS warning would prompt 56% to leave, and a Level 3 multi-tiered LEWS warning would prompt 58% to leave. In other words, the participants were more likely to take active measures when a multi-tiered warning was in place, even if it was only Level 1. At Level 3, two-thirds of the participants would leave for a safe place or shelter.

Conclusion

Using a hybrid approach of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies with nearly 2000 participants, our research explored the public’s understanding of landslides in Hong Kong and their perceptions of the current LEWS, along with the concept of a multi-tiered LEWS. The key findings were as follows:

-

1.

Few of the participants saw the connection between global warming and landslides. Although many were aware that global warming affects weather conditions in Hong Kong, the majority related that effect to the increase in temperature (82%) and the disappearance of winter (72%). Only 37% of the participants realized the connection between global warming and landslides (the lowest percentage among the ten weather conditions included in the survey).

-

2.

Slope safety work has clearly improved over the last decade, and landslides are a remote concern, even for those living in landslide-prone areas where 91% of our participants believed that their neighborhoods are not at risk. Although only 4% of the participants and their families had experienced landslides, it is prudent to infer that there is some awareness of the landslide risk in the society. Furthermore, more than 80% believed that slope safety problems have improved over the last decade and that slopes in Hong Kong are generally safe. Although the results imply that the GEO’s impressive slope safety work has gained public recognition, they also reveal the public’s false sense of safety from landslides created by that work.

-

3.

Although the participants were widely aware of the current LEWS, they paid insufficient attention to it. Most importantly, of the 1320 participants who reported not being concerned about the current LEWS in the survey interviews, 65% believed that it does not impact their residential or activity areas (e.g., school/work arrangements).

-

4.

The concept of a multi-tiered LEWS was positively received, demonstrating its soundness in communication, alertness, call to action, and crisis management. Compared with the current LEWS, the multi-tiered LEWS’s provision of additional public information about landslide severity appeared to be more effective in communicating the risk levels and increasing public alertness. The multi-tiered LEWS was also perceived as more effective in reminding people to take appropriate precautionary measures and reducing landslide-related casualties. Although 89% of the participants found the multi-tiered LEWS easy to understand, those living in landslide-prone areas expected the provision of more specific precautionary measures or actions for each tier.

The current research is not without limitations. For the focus groups, we recruited the participants from landslide-prone (rural) areas, alongside media representatives with prior collaborations with the GEO, who might have been more aware of landslide issues and the current LEWS than the general population in Hong Kong. To map a comprehensive picture of landslide risks, it is also important to consult residents in urban areas through focus groups. After all, the general public living in the urban areas might have different concerns and reactions to landslide risks that were not captured by our rural participants. Furthermore, although we pilot-tested the concept of a three-tiered public alert system, it is certainly not a unique concept. Japan’s five-tiered system has also been in place since 2007 and Rio de Janeiro’s four-tiered has been in place since 2010, raising a question about whether a four- or even five-tiered system drives stronger and clearer precautionary actions than a three-tiered system. This is certainly an important but understudied issue.

In summary, the concept of a multi-tiered LEWS system was perceived to introduce significant improvements in communication, alertness, call to action, and crisis management compared with the current single-tiered LEWS. The multi-tiered system may be more effective in mobilizing the public to proactively take precautionary measures, although further research is needed to demonstrate how this concept can be implemented together with other warnings (e.g., rainstorms) during extreme weather conditions. Finally, public education is foundational for improving the public’s knowledge of landslides and enhancing their readiness to deal with them. This study’s method of utilizing focus groups and questionnaires to survey the public on perceptions of landslide risks and warnings provides a framework for how to involve the public as stakeholders, producing invaluable information regarding the effectiveness of current and conceptual changes to the current LEWS. The questionnaire developed in the current research was contextualized for local usage, setting an example of procuring “indigenous” questions for use in other countries investigating public perceptions of landslide warning systems or other public warning systems (see also Scolobig 2016).

Notes

The public Landslip Warning is issued when there is a forecast of 15 or more landslides based on any or multiple of the four thresholds: (a) past 24-h of rainfall, (b) past 23- and 1-h forecasted rainfall, (c) past 22- and 2-h forecasted rainfall, and (d) past 21- and 3-h forecasted rainfall.

In Hong Kong, people primarily speak Cantonese and write using traditional Chinese characters.

References

Baum RL, Godt JW (2010) Early warning of rainfall-induced shallow landslides and debris flows in the USA. Landslides 7:259–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-009-0177-0

Blikra LH, Jogerud K, Hole J, Bergeng T (2007) Åknes/Tafjord prosjektet—status og framdrift for overvåking og beredskap. Report 01–2007. www.aknes-tafjord.no, 30p

Calvello M, d’Orsi RN, Piciullo L, Paes N, Magalhaes MA, Lacerda WA (2015) The Rio de Janeiro early warning system for rainfall-induced landslides: analysis of performance for the years 2010–2013. Int J Disast Risk Reduc 12:3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.10.005

CEDD (2014) When hillside collapse: a century of landslides in Hong Kong. Civil Engineering and Development Department, HKSAR Government, 2nd edn

Chan RKS, Pang PLR, Pun WK (2003) Recent developments in the landslip warning system in Hong Kong. Proceedings of the 14th Southeast Asian Geotechnical Conference. Balkema, Lisse, The Netherlands, pp 137–151

Cheung RWM (2021) Landslide risk management in Hong Kong. Landslides 18:3457–3473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-020-01587-0

Choi KY, Cheung RWM (2013) Landslide disaster prevention and mitigation through works in Hong Kong. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng 5(5):354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2013.07.007

Froude MJ, Petley DN (2018) Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 18:2161–2181. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-18-2161-2018

Gariano SL, Guzzetti F (2016) Landslides in a changing climate. Earth-Sci Rev 162:227–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.08.011

Guzzetti F, Gariano SL, Peruccacci S, Brunetti MT, Marchesini I, Rossi M, Melillo M (2020) Geographical landslide early warning systems. Earth-Sci Rev 200:102973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102973

Ho K, Lacasse S, Picarelli L (2016) Slope safety preparedness for impact of climate change. CRC Press, 1st edn. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315387789

Keegan M (2022) How Hong Kong protects people from dangerous landslides. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220225-how-hong-kong-protects-people-from-its-deadly-landslides. Accessed 21 June 2022

Kong VWW, Kwan JSH, Pun WK (2020) Hong Kong’s landslip warning system—40 years of progress. Landslides 17:1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-020-01379-6

Lacasse S, Nadim F (2009) Landslide risk assessment and mitigation strategy. In: Sassa K, Canuti P (ed) Landslides—Disaster risk reduction. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 31–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-69970-5_3

Michoud C, Bazin S, Blikra LH, Derron MH, Jaboyedoff M (2013) Experiences from site-specific landslide early warning systems. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 13(10):2659–2673. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-2659-2013

Pun WK, Chung PWK, Wong TKC, Lam HWK, Wong LA (2020) Landslide risk management in Hong Kong—experience in the past and planning for the future. Landslides 17:243–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-019-01291-8

Sassa K (2017) The 2017 Ljubljana Declaration on landslide risk reduction and the Kyoto 2020 Commitment for global promotion of understanding and reducing landslide disaster risk. Landslides 14:1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-017-0857-0

Sassa K, Picarelli L (2010) Preface for the thematic issue “Early warning of landslides.” Landslides 7:217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-010-0233-9

Scolobig A (2016) Stakeholder perspectives on barriers to landslide risk governance. Nat Hazards 81:27–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-1787-6

Scolobig A, Thompson M, Linnerooth-Bayer J (2016) Compromise not consensus: designing a participatory process for landslide risk mitigation. Nat Hazards 81(S1):45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-2078-y

Wong MC, Mok HY, Lee TC (2011) Observed changes in extreme weather indices in Hong Kong. Int J Climatol 31:2300–2311. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2238

World Economic Forum (2022) The global risks report 2022 (17th edn) https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2022.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2022

Yu YF, Lam JS, Siu CK, Pun WK (2004) Recent advance in Landslip Warning System. Proceedings of the Seminar on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Engineering, Hong Kong, pp 139–147

Acknowledgements

This paper is published with the permission of the Director of Civil Engineering and Development, Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The authors would like to thank Regis Chee, Raymond Cheung, George Lau, Dawnie Ng, and Irene Sze for their help in preparing this article.

Funding

Preparation of the paper was facilitated by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council’s Area of Excellence Scheme (Project AoE/E-603/18) and General Research Fund (Project 16601818). Felity Kwok received support from the Hong Kong PhD Fellowship Scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yik, M., Pun, W.K., Kwok, F.H.C. et al. Perceptions of landslide risks and warnings in Hong Kong. Landslides 20, 1211–1224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-022-02021-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-022-02021-3