Abstract

Lateralization is a fundamental principle of the brain organization widespread among vertebrates but rather unknown in invertebrates. Evidences of lateralized courtship and mating behavioral traits in parasitic wasps are extremely rare. Here, courtship and mating sequences and the presence of mating lateralization in Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci, one of the most effective biological control agents of mealybugs, were investigated. Courtship and mating behavior in A. sp. near pseudococci consisted in the male chasing of the female, pre-copula, copula, and post-copula phases. Males mating success was not related to the duration of chasing and pre-copula. High-speed videos showed population-level lateralization in A. sp. near pseudococci during courtship. Most the wasps used the right antenna to start antennal tapping and this led to a higher mating success, although lateralization had no impact on the frequency of the antennal tapping. Both females and males displayed this behavior. Higher mating success was detected when females displayed antennal tapping during sexual interaction, though male tapping was performed with a slightly higher frequency. To the best of our knowledge, this report on behavioral asymmetries of mating traits in A. sp. near pseudococci represents a quite rare evidence of lateralized behavior in parasitic wasps of economic importance. Our findings add basic knowledge on the behavioral ecology of this biocontrol agent with potential implications on the optimization of mass-rearing procedures aimed at using this parasitoid in Integrated Pest Management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Key message

-

Evidences of asymmetric mating traits in parasitic wasps are limited

-

We studied mating laterality in Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci, a biocontrol agent of mealy bugs

-

High-speed videos showed population-level lateralization during courtship

-

Lateralization had no impact on the frequency of the antennal tapping

-

Parasitoids used the right antenna to start antennal tapping; this led to higher mating success

Introduction

Lateralization (i.e., the different specialization of the right and left sides of the nervous system reflected in left–right behavioral asymmetries) is a fundamental principle of the brain organization widespread among vertebrates (Rogers et al. 2013a, b; Vallortigara et al. 2011; Vallortigara and Rogers 2005; Vallortigara and Versace 2017). Recent evidences support the hypothesis that lateralization can increase neural capacity, enabling the brain to perform simultaneous processing (Vallortigara 2000; Vallortigara and Rogers 2005). Later, it has been highlighted that also invertebrates, endowed with simpler nervous systems, showed lateralized traits (Ades and Ramires 2002; Backwell et al. 2007; Benelli et al. 2015a, b, c; Rigosi et al. 2015; Rogers and Vallortigara 2008, 2015; Rogers et al. 2013a, b, 2016; Romano et al. 2015, 2016a; Versace and Vallortigara 2015). However, behavioral asymmetries in insects are still scarcely investigated (Frasnelli et al. 2012). Behavioral asymmetries of courtship and mating behavior represent a fascinating issue. Recently, lateralized displays in the courtship and mating behavior have been reported for tephritid flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) (Benelli et al. 2015c), stored product beetles such as the confused flour beetle (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), the khapra beetle (Coleoptera: Dermestidae), and the rice weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (Benelli et al. 2017a, b; Romano et al. 2016a), earwigs (Dermaptera: Labiduridae) (Kamimura 2006), and the parasitoid Leptomastidea abnormis (Girault) (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) (Romano et al. 2016b).

Basic knowledge about the presence of behavioral asymmetries in parasitic wasps is extremely scarce. To the best of our knowledge, this topic was investigated for the first time in parasitic wasps by Romano et al. (2016b). These authors reported that the encyrtid L. abnormis showed a population-level lateralization of male courtship display, with right-biased male antennal tapping (i.e., a key step during courtship that allows the acquisition of information about mate quality) on the female’s head. However, a deeper understanding of laterality of mating traits in parasitoids may lead to the optimization of mass-rearing monitoring processes, helping to explain potential mating failures (Giunti et al. 2015).

Anagyrus pseudococci (Girault) is a koinobiont endoparasitoid commonly used worldwide as a biological control agent against mealybugs (Planococcus spp. and Pseudococcus spp.) (Daane et al. 2012; Fortuna et al. 2015; Heidari and Jahan 2010). Triapitsyn et al. (2007) demonstrated the existence of two morphotypes in the population of A. pseudococci released in biological control projects carried out in California for the management of Planococcus ficus (Signoret). The two morphotypes differed only for the color of the first antennal funicle segment of the female, partially black (basal half) and white (distal half) in Anagyrus pseudococci (Girault), and entirely black in the other morphotype, which was named Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci (Girault). Anagyrus pseudococci is known only from Sicily (Italy), Argentina, and Cyprus, A. sp. near pseudococci occurs in the Mediterranean countries (Sicily included), in the Palaearctic Asia, in Brazil and USA. This study deals with the latter species, which is the one mass-reared and commercialized by BioPlanet (Cesena, Italy).

While several studies have been conducted on host–parasitoid interactions of A. sp. near pseudococci (Franco et al. 2008; Güleç et al. 2007; Heidari and Jahan 2010; Suma et al. 2012), no information is available about its courtship behavior. Notably, A. sp. near pseudococci females rely on their antennae, endowed with sophisticated sensilla, performing antennal tapping during host location and selection (Bugila et al. 2014; Fortuna et al. 2015). Since a left-biased lateralized antennal tapping has been recently reported at population level in L. abnormis, a close-related encyrtid species (Romano et al. 2016b), we hypothesized a key role of lateralized of antennal tapping during courtship and mating behavior of A. sp. near pseudococci. Therefore, in this research, the courtship and mating behavior of A. pseudococci were investigated under laboratory conditions, producing an ethogram. Furthermore, antennal tapping frequencies, their laterality, and the following success in mating approaches were characterized based on the analysis of high-speed video recordings.

Materials and methods

Insect rearing and general observation

Commercially mass-reared specimens of A. sp. near pseudococci were provided before adult emergence by BioPlanet (Cesena, Italy). Immediately after emergence, parasitoids were sexed, singly stored in clean glass vials, and fed with a tiny drop of water and honey 1:1 (v:v). Virgin sexually mature males and females (aged 2 days) were used in all observations. All experiments were conducted during June 2016 in laboratory conditions described by Romano et al. (2016b). All experiments were carried out in a Petri dish arena (50 mm diam. × 10 mm high) from 10:00 to 18:00 h. The arena was surrounded by a white wall of filter paper (Whatman No. 1, height 30 cm), to reduce the effect of external cues that could affect the A. sp. near pseudococci behavior (Benelli and Canale 2012).

Courtship and mating

To investigate courtship and mating behavior of A. sp. near pseudococci, a virgin male and five virgin females were gently transferred into a testing arena using a clean glass vial (diam. 10 mm; length 50 mm). Male behavior was focally observed for 45 min, or until the end of mating. For each replica, we observed the duration of the following phases: (i) chasing (i.e., time spent by the male following the female); (ii) pre-copula (i.e., time spent by the male mounting the female, until genital contact); (iii) copula (i.e., from the male’s insertion of the aedeagus into the female genital chamber until genital disengagement); (iv) post-copula (i.e., time spent by the male on the female’s thorax or motionless on the substrate close to the female, after genital disengagement); and (v) the duration of the whole courtship and mating sequence. Successful and unsuccessful mating attempts were noted. A total of 47 insect pairs were tested. Males and females that did not engage any courtship approach or did not move for more than 30 min were discarded. Thirty mating pairs were considered for statistical analysis.

Antennal tapping video characterization

Preliminary observations revealed that antennal tapping during courtship behavior can be performed by A. sp. near pseudococci males and females. We video-recorded the antennal tapping behavior performed by males or females during courtship behavior. Only a single antennal tapping sequence was analyzed for each wasp (Benelli et al. 2012), to avoid pseudo-replications. The video recording began once a male mounted a female and the antennal tapping started. The mean pulse frequency (Hz) (i.e., the inverse of the average duration of the tapping during antennation recorded throughout the frame-by-frame analysis at a rate of 1000 frames per second [fps] of video recordings) and the relationship between frequency and mating success were analyzed. Furthermore, we evaluated the presence of population-level behavioral asymmetries in A. sp. near pseudococci by observing which antenna was used to palpate the partner first and whether behavioral asymmetries had any effect on male mating success. Sex differences in antennal tapping frequency and lateralization were also noted.

Eighty-nine pairs of insects were tested. Females constrained in confined spaces were discarded; for laterality observations, we considered only females that are approached by males when they were free in the middle of the arena (Romano et al. 2016b). We analyzed 50 mating pairs performing antennal tapping during the courtship behavior.

The high-speed video recordings were made using a HotShot 512 SC high-speed video camera (NAC Image Technology Inc., Simi Valley, CA, USA). Sequential images from each antennal tapping were captured at a rate of 1000 fps with an exposure time of 1 ms and a video duration of 8.20 s (Romano et al. 2016b). The area where insects were expected to perform antennal tapping was lit with four LED illuminators (RODER SRL, Oglianico, TO, Italy) that emit light (420 lm each) at k = 628 nm (Briscoe and Chittka 2001).

Data analysis

Data concerning courtship duration, mating duration, and mating success were analyzed with JMP 7 (SAS, 1999). Data normality was checked using Shapiro–Wilk test (P < 0.05). The variance between values was analyzed with Fisher’s F-test (P < 0.05). Differences in pre-copula duration, copula duration, and whole duration of the mating sequence were analyzed using a general linear model with a normal error structure and two fixed factors (i.e., laterality and mating outcome; P < 0.05; Benelli et al. 2017b). Differences in male and female antennal tapping frequency were analyzed using a general linear model with a normal error structure and three fixed factors (i.e., laterality, sex, and mating outcome; P < 0.05).

Differences in male mating success were analyzed using a generalized linear model with a binomial error structure and one fixed factor (laterality): y = Xß + ε where y is the vector of the observations (i.e., the male success or failure), X is the incidence matrix, ß is the vector of fixed effects (i.e., laterality), and ε is the vector of the random residual effects. A probability level of P < 0.05 was used to assess the significance of differences among values.

Laterality differences between the numbers of parasitoids using left or right antennae during courtship approaches were analyzed using a χ 2 test with Yates correction (P < 0.05; Sokal and Rohlf 1981).

Concerning the high-speed video recordings of parasitoid courtship and mating, to check inter-rater reliability among laterality data, two blind observers re-analyzed a subset of the data [i.e., 39 high-speed videos (video ID numbers: 1–9, 11–19, 21, 22, 24–26, 28–30, 32, 35, 37–39, 41–44, 46–49); Bisazza et al. 2001]. Inter-rater reliability was calculated (Cohen 1960; Gwet 2014; Romano et al. 2016b). The concordance index was 0.95, and Cohen’s kappa was 0.874.

Results

Courtship and mating behavior

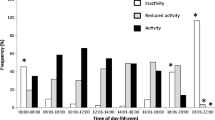

Courtship and mating sequence of A. sp. near pseudococci is quantified in the ethogram depicted in Fig. 1. After the detection of a female, the male started chasing her and then attempt to mount on the thorax of the female, which constantly walked, and the pre-copula phase started. Receptive females bend dorsally their abdomen allowing the insertion of the aedeagus into their genital chamber. At the end of the copula, genital disengagement occurred and the male remounted for a short period the female or stayed still on the substrate close to her (Fig. 1). Results showed that no significant differences in the duration of chasing (F 1,29 = 0.006; P = 0.941), pre-copula (F 1,29 = 0.027; P = 0.872), and the whole courtship and mating sequence (F 1,29 = 2.900; P = 0.100) were detected between successful and unsuccessful mating approaches (Fig. 2).

a Ethogram quantifying the courtship and mating behavior of the encyrtid parasitoid Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci. b Presence of lateralized antennal tapping behavior in males and female wasps during courtship. The thickness of each arrow indicates the proportion of individuals displaying different behavioral phases. Green arrows indicate females showing right-biased antennal tapping, red arrows showed females using first the left antenna. Orange arrows indicate males showing right-biased antennal tapping, brown arrows showed males using first the left antenna. (Color figure online)

High-speed video characterization of lateralized antennal tapping

In A. sp. near pseudococci, the antennal tapping was displayed both by females (60% of the observed wasps) and by males (40%; Fig. 1b). Mating success was higher when females displayed antennal tapping during sexual interactions (χ 2 = 4.818; d.f. = 1; P = 0.029) (Fig. 3). In addition, males displaying antennal tapping performed it with slightly higher frequencies, compared to females (F 1,49 = 7.2689; P = 0.010; Fig. 4).

a Impact of male and female antennal tapping behavior on Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci mating success. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (generalized linear model, P < 0.05); n.s. not significant. b Influence of left-biased and right-biased antennal tapping on A. sp. near pseudococci mating success. Above each column, different letters indicate significant differences (generalized linear model, P < 0.05)

The preferential use of the right antenna to start antennal tapping led to higher mating success, compared to left-biased interactions (χ 2 = 7.589; d.f. = 1; P = 0.006) (Fig. 3). However, the lateralized use of antennae showed no effect on antennal tapping frequency (F 1,49 = 0.004; P = 0.953) (Fig. 4). As a general trend, slightly higher frequencies of antennal tapping were observed in successful mating pairs (F 1,49 = 4.726; P = 0.035) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Recently, asymmetries of mating traits have been found in several insect species (Benelli et al. 2015c, 2017a; Romano et al. 2016a, b), suggesting that laterality would have crucial relevance in the acceptance and coordination of two conspecifics during courtship and mating behavior. It has been argued that lateralization at population level has evolved as a characteristic feature of social species, while solitary species display more frequently asymmetries at individual level (Ghirlanda and Vallortigara 2004; Vallortigara and Rogers 2005; Vallortigara 2006; Ghirlanda et al. 2009; Rogers and Vallortigara 2008, 2015; Rogers et al. 2013a). However, a number of recent studies on invertebrates reported population-level lateralization in different solitary species, proposing that behavioral asymmetries in solitary animals could be related to frequent and prolonged social or “almost social” interactions occurring during their life cycle, such as courtship and mating and/or agonistic approaches (Ades and Ramires 2002; Backwell et al. 2007; Frasenelli et al. 2012; Benelli et al. 2015a, b, c, 2017a; Romano et al. 2015, 2016a, b). Focusing on insect courtship and mating behavior, recent research reported evidences of lateralized mating traits in earwigs (Kamimura 2006), olive fruit flies (Benelli et al. 2015c), rice weevils and confused flour beetles (Benelli et al. 2017a; Romano et al. 2016a), and even a parasitoid species (Romano et al. 2016b).

In this study, we investigated the poorly known courtship and mating behavior of the parasitic wasp A. sp. near pseudococci, a biological control agent of mealybugs, showing a lateral bias in the sexual interactions. Our observations allowed describing the mating sequences of this species that included the chasing of the female by the male and a pre-copula phase, where the male mounts the female courting her until copula occurs. In addition, a post-copula phase was observed, where the male remounted for few seconds the female and/or the mating pairs stay still and close each other. According to our data, mating success was not related to the duration of chasing or pre-copula phases. Furthermore, lateralization of the antennal tapping performed during the pre-copula in A. sp. near pseudococci was evaluated, revealing that both females and males of this parasitoid exhibited a tendency in using the right antenna over the left one, when started antennal tapping session. In agreement with our results, a right-biased antennal tapping was also observed during the courtship of L. abnormis (Romano et al. 2016b), another encyrtid species occupying an ecological niche closely related to that of A. sp. near pseudococci, even if with lower-temperature requirements (Tingle and Copland 1989). However, while in L. abnormis only the males perform antennal tapping on the potential mate (Romano et al. 2016b), in A. sp. near pseudococci, antennal tapping was displayed by both sexes. In addition, the males of A. sp. near pseudococci carried out antennal tapping with a slightly higher level of pulse frequency over females, and the mating success was higher in mating pairs where females bring up the antennae to palpate those of males, which were held forward and still during the mount. We hypothesize that males produced aphrodisiac secretions on antennal glands inducing antennal tapping in females. Indeed, it has been reported that A. sp. near pseudococci presents sexual dimorphism of antennae, since male’s antennae are provided with sophisticated glandular structures that are absent in the females (Fortuna et al. 2015). Therefore, the production of alluring substances could act as a selective mechanism to persuade females on the male quality (see also Benelli and Romano 2017; Romano et al. 2016a).

Interestingly, from an intra-sexual point of view, individuals performing antennal tapping with slightly higher frequency of pulses outperformed individuals with lower values of the frequency of antennal tapping in terms of mating success. This indicates the important role that tactile stimuli play, aside olfactory cues, in better allocating or harvesting contact pheromones. Finally, A. sp. near pseudococci used preferentially the right antenna to start antennal tapping behavior. In addition, right-biased individuals were more successful in mating. This phenomenon may be due to the prolonged mating interaction occurring also in other insect species including another encyrtid (Benelli et al. 2015c, 2017a; Romano et al. 2016a, b) as well as may be due to a higher number of sensory structures and/or glandular areas on the right antenna (Anfora et al. 2010; Hädicke et al. 2016; Romano et al. 2016b).

To the best of our knowledge, this report on behavioral asymmetries of mating traits in A. sp. near pseudococci represents a quite rare evidence of lateralized behavior in parasitic wasps of economic importance. Our findings add basic knowledge to the behavioral ecology of this biocontrol agent with potential implications on the optimization of mass-rearing procedures aimed to employ this parasitoid in Integrated Pest Management.

Author contributions

DR and GB designed the research and conducted the experiments. All authors analyzed data and contributed new reagents and/or analytical tools. All authors wrote and approved the manuscript.

References

Ades C, Ramires EN (2002) Asymmetry of leg use during prey handling in the spider Scytodes globula (Scytodidae). J Insect Behav 15:563–570. doi:10.1023/A:1016337418472

Anfora G, Frasnelli E, Maccagnani B, Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G (2010) Behavioural and electrophysiological lateralization in a social (Apis mellifera) but not in a non-social (Osmia cornuta) species of bee. Behav Brain Res 206:236–239. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.023

Backwell PRY, Matsumasa M, Double M, Roberts A, Murai M, Keogh JS, Jennions MD (2007) What are the consequences of being left-clawed in a predominantly right-clawed fiddler crab? Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 274:2723–2729. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0666

Benelli G, Canale A (2012) Learning of visual cues in the fruit fly parasitoid Psyttalia concolor (Szépligeti) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Biocontrol 57:767–777. doi:10.1007/s10526-012-9456-0

Benelli G, Romano D (2017) Does indirect mating trophallaxis boost male mating success and female egg load in Mediterranean fruit flies? J Pest Sci. doi:10.1007/s10340-017-0854-z

Benelli G, Canale A, Bonsignori G, Ragni G, Stefanini C, Raspi A (2012) Male wing vibration in the mating behavior of the olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) (Diptera: Tephritidae). J Insect Behav 25:590–603. doi:10.1007/s10905-012-9325-9

Benelli G, Donati E, Romano D, Stefanini C, Messing RH, Canale A (2015a) Lateralization of aggressive displays in a tephritid fly. Sci Nat Naturwiss 102(1–2):1–9. doi:10.1007/s00114-014-1251-6

Benelli G, Romano D, Messing RH, Canale A (2015b) First report of behavioural lateralisation in mosquitoes: right-biased kicking behaviour against males in females of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus. Parasitol Res 114:1613–1617. doi:10.1007/s00436-015-4351-0

Benelli G, Romano D, Messing RH, Canale A (2015c) Population-level lateralized aggressive and courtship displays make better fighters not lovers: evidence from a fly. Behav Process 115:163–168. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2015.04.005

Benelli G, Romano D, Stefanini C, Kavalieratos NG, Athanassiou CG, Canale A (2017a) Asymmetry of mating behaviour affects copulation success in two stored product beetles. J Pest Sci. doi:10.1007/s10340-016-0794-z

Benelli G, Romano D, Kavallieratos N, Conte G, Stefanini C, Mele M, Athanassiou C, Canale A (2017b) Multiple behavioural asymmetries impact male mating success in the khapra beetle, Trogoderma granarium. J Pest Sci 90:901–909. doi:10.1007/s10340-017-0832-5

Bisazza A, Sovrano VA, Vallortigara G (2001) Consistency among different tasks of left–right asymmetries in lines of fish originally selected for opposite direction of lateralization in a detour task. Neuropsychologia 39:1077–1085. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00034-3

Briscoe AD, Chittka L (2001) The evolution of colour vision in insects. Annu Rev Entomol 46:471–510. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.471

Bugila AA, Branco M, Silva EBD, Franco JC (2014) Host selection behaviour and specificity of the solitary parasitoid of mealybugs Anagyrus sp. nr. pseudococci (Girault)(Hymenoptera, Encyrtidae). Biocontrol Sci Technol 24(1):22–38

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 20:37–46

Daane KM, Almeida RPP, Bell VA, Walker JTS, Botton M, Fallahzadeh M, Mani M, Miano LL, Sforza R, Walton VM, Zaviezo T (2012) Biology and management of mealybugs in vineyards. In: Bostanian NJ, Vincent C, Isaacs R (eds) Arthropod management in vineyards. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 271–307. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4032-7_12

Fortuna TM, Franco JC, Rebelo MT (2015) Morphology and distribution of antennal sensilla in a mealybug parasitoid, Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci (Hymenoptera, Encyrtidae). Microsc Microanal 21(S6):8–9

Franco JC, Silva EB, Cortegano E, Campos L, Branco M, Zada A, Mendel Z (2008) Kairomonal response of the parasitoid Anagyrus spec. nov. near pseudococci to the sex pheromone of the vine mealybug. Entomol Exp Appl 126(2):122–130

Frasnelli E, Iakovlev I, Reznikova Z (2012) Asymmetry in antennal contacts during trophallaxis in ants. Behav Brain Res 232(1):7–12

Ghirlanda S, Vallortigara G (2004) The evolution of brain lateralization: a game theoretical analysis of population structure. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 271:853–857

Ghirlanda S, Frasnelli E, Vallortigara G (2009) Intraspecific competition and coordination in the evolution of lateralization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 364:861–866

Giunti G, Canale A, Messing RH, Donati E, Stefanini C, Michaud JP, Benelli G (2015) Parasitoid learning: current knowledge and implications for biological control. Biol Control 90:208–219

Güleç G, Kilinçer AN, Kaydan MB, Ülgentürk S (2007) Some biological interactions between the parasitoid Anagyrus pseudococci (Girault) (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) and its host Planococcus ficus (Signoret) (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Pseudococcidae). J Pest Sci 80(1):43–49

Gwet KL (2014) Handbook of inter-rater reliability: The definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement among raters. Advanced Analytics LLC, Stataxis Publishing Company, Gaithersburg

Hädicke CW, Ernst A, Sombke A (2016) Sensing more than the bathroom: sensilla on the antennae, cerci and styli of the silverfish Lepisma saccharina Linneaus, 1758 (Zygentoma: Lepismatidae). Entomol Gen 36:71–89

Heidari M, Jahan M (2010) A study of ovipositional behaviour of Anagyrus pseudococci a parasitoid of mealybugs. J Agr Sci 2:49–53

Kamimura Y (2006) Right-handed penises of the earwig Labidura riparia (Insecta, Dermaptera, Labiduridae): evolutionary relationships between structural and behavioral asymmetries. J Morphol 267:1381–1389

Rigosi E, Haase A, Rath L, Anfora G, Vallortigara G, Szyszka P (2015) Asymmetric neural coding revealed by in vivo calcium imaging in the honey bee brain. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 282(1803):20142571

Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G (2008) From antenna to antenna: lateral shift of olfactory memory in honeybees. PLoS ONE 3(6):e2340. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002340

Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G (2015) When and why did brains break symmetry? Symmetry 7:2181–2194

Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G, Andrew RJ (2013a) Divided brains: The biology and behaviour of brain asymmetries. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rogers LJ, Rigosi E, Frasnelli E, Vallortigara G (2013b) A right antenna for social behaviour in honeybees. Sci Rep 3:2045. doi:10.1038/srep02045

Rogers LJ, Frasnelli E, Versace E (2016) Lateralized antennal control of aggression and sex differences in red mason bees, Osmia bicornis. Sci Rep 6:29411

Romano D, Canale A, Benelli G (2015) Do right-biased boxers do it better? Population-level asymmetry of aggressive displays enhances fighting success in blowflies. Behav Process 113:159–162

Romano D, Kavallieratos NG, Athanassiou CG, Stefanini C, Canale A, Benelli G (2016a) Impact of geographical origin and rearing medium on mating success and lateralization in the rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J Stored Prod Res 69:106–112

Romano D, Donati E, Canale A, Messing RH, Benelli G, Stefanini C (2016b) Lateralized courtship in a parasitic wasp. Laterality 21(3):243–254

Sokal RK, Rohlf FJ (1981) Biometry. Freeman and Company, New York

Suma P, Mansour R, La Torre I, Ali Bugila AA, Mendel Z, Franco JC (2012) Developmental time, longevity, reproductive capacity and sex ratio of the mealybug parasitoid Anagyrus sp. nr. pseudococci (Girault) (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae). Biocontrol Sci Technol 22(7):737–745

Tingle CCD, Copland MJW (1989) Progeny production and adult longevity of the mealybug parasitoids Anagyrus pseudococci, Leptomastix dactylopii, and Leptomastidea abnormis [Hym.: Encyrtidae] in relation to temperature. Entomophaga 34(1):111–120

Triapitsyn SV, Gonzàlez D, Vickerman DB, Noyes JS, White EB (2007) Morphological, biological, and molecular comparisons among the different geographical populations of Anagyrus pseudococci (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae), parasitoids of Planococcus spp. (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae), with notes on Anagyrus dactylopii. Biol Control 41:14–24

Vallortigara G (2000) Comparative neuropsychology of the dual brain: a stroll through animals’ left and right perceptual worlds. Brain Lang 73(2):189–219

Vallortigara G (2006) The evolutionary psychology of left and right: costs and benefits of lateralization. Dev Psychobiol 48(6):418–427

Vallortigara G, Rogers LJ (2005) Survival with an asymmetrical brain: advantages and disadvantages of cerebral lateralization. Behav Brain Sci 28:575–633

Vallortigara G, Versace E (2017) Laterality at the neural, cognitive, and behavioral levels. In: Call J (ed) APA handbook of comparative psychology: vol. 1. basic concepts, methods, neural substrate, and behavior. American Psychological Association, Washington DC, pp 557–577

Vallortigara G, Chiandetti C, Sovrano VA (2011) Brain asymmetry (animal). Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 2:146–157. doi:10.1002/wcs.100

Versace E, Vallortigara G (2015) Forelimb preferences in human beings and other species: multiple models for testing hypotheses on lateralization. Front Psychol 6:233. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00233

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Sala (BioPlanet, Cesena, Italy) for providing the mass-reared parasitoids tested in this study. We would like to thank Alice Bono for her kind assistance during high-speed video recordings. Giovanni Benelli is funded by BIOCONVITO P.I.F. “Artigiani del Vino Toscano” (Regione Toscana, Italy). This study was partially supported by the H2020 Project “Submarine cultures perform long-term robotic exploration of unconventional environmental niches” (subCULTron) [640967FP7]. Funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All applicable international and national guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted.

Additional information

Communicated by M. Traugott.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Romano, D., Benelli, G., Stefanini, C. et al. Behavioral asymmetries in the mealybug parasitoid Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci: does lateralized antennal tapping predict male mating success?. J Pest Sci 91, 341–349 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0903-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0903-7