Abstract

Regional variations in tool use among chimpanzee subspecies and between populations within the same subspecies can often be explained by ecological constraints, although cultural variation also occurs. In this study we provide data on tool use by a small, recently isolated population of the endangered Nigeria–Cameroon chimpanzee Pan troglodytes ellioti, thus demonstrating regional variation in tool use in this rarely studied subspecies. We found that the Ngel Nyaki chimpanzee community has its own unique tool kit consisting of five different tool types. We describe a tool type that has rarely been observed (ant-digging stick) and a tool type that has never been recorded for this chimpanzee subspecies or in West Central Africa (food pound/grate stone). Our results suggest that there is fine- scale variation in tool use among geographically close communities of P. t. ellioti, and that these variations likely reflect both ecological constraints and cultural variation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Regional variation in tool use among chimpanzees is well documented (McGrew 1992; Whiten et al. 1999; Humle 2003). For example, the use of wood or stones to crack nuts has only been observed in West Africa (Boesch et al. 1994; Matsuzawa 1994; Humle 2003) and in Cameroon (Morgan and Abwe 2006) and termite mound perforators have only been observed in the Republic of Congo (Sanz et al. 2004).

Chimpanzees use various tools and techniques to obtain honey and brood from Apini (honey) and Meliponini (stingless) bee nests. The use of clubs to pound into arboreal bee nests appears limited to Central Africa (Fay and Carroll 1994; Hicks et al. 2005; Sanz and Morgan 2009). Complex tool sets to extract honey from subterranean nests have only been documented in Central Africa (Boesch et al. 2009; Sanz and Morgan 2009) while West African chimpanzees mainly use their hands (Boesch and Boesch 1990).

Chimpanzees use tools to prey on a range of ant species (Schöning et al. 2007) and these tools are usually designed to provoke ants to attack and cling to them. ‘Ant dipping’ (McGrew 1974) for terrestrial ants involves the use of modified sticks (wands), stems or blades of grass, while ‘fishing’ (Sanz et al. 2010) for arboreal ant species involves the use of slender probes. Again, there is much regional variation in ant tools (Tutin et al. 1995; Hicks et al. 2005; Fowler and Sommer 2007; Sanz et al. 2010; Yamamoto et al. 2011), some of which obviously reflects different prey species or materials available for tool use. However, some of the variation described above may be cultural and most likely reflects complex interactions between ecological constraints, genetic variation and culture (Humle 2010). Observing variation among geographically close communities does, however, help to reduce the genetic and ecological components of variation and therefore provide evidence for cultural variation (Whiten et al. 1999; van Schaik 2009).

Previous observations on tool use in the rare Nigeria–Cameroon subspecies Pan troglodytes ellioti are from the Ebo Forest, Cameroon (Morgan and Abwe 2006; Abwe and Morgan 2008) and Gashaka Gumti National Park (from here on in this paper referred to as Gashaka), Nigeria (Fowler 2006; Fowler and Sommer 2007). In Ebo Forest, there is evidence of the chimpanzees using termite fishing tools (Abwe and Morgan 2008) and four tool combinations for cracking Coula edulis nuts (wooden anvil and wooden hammer, stone hammer and wooden anvil, stone hammer and stone anvil; stone hammer without anvil; Morgan and Abwe 2006). In Gashaka, chimpanzees use stingless bee digging and probing sticks to access both arboreal and ground nests of the largest type of stingless bees (Meliponula, Plebeina; Sommer et al. 2012), Dorylus ant dipping wands (Schöning et al. 2007) and ant fishing rods for Camponotus arboreal nests (Fowler and Sommer 2007).

The Gashaka population is only 25 km away in a straight line from our study site, Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve and until recently the two populations will have been connected to some extent genetically (Knight 2013). Here we provide evidence of a unique tool assemblage used by the small, nearly isolated Ngel Nyaki population. The aims of our study were to add to what little is published about tool use by P. t. ellioti by: (1) documenting tools and tool use within Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve, and (2) determining if this population shows differences/similarities in tool use with the lowland Gashaka population (Fowler and Sommer 2007). As outlined above, such information will contribute towards understanding the interplay of ecology, genetics and culture on tool use in P. t. ellioti.

Methods

Study site

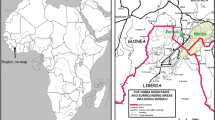

A community of approximately 18 chimpanzees (P. t. ellioti; Dutton et al. 2014) reside within the 46 km2 of Ngel Nyaki forest reserve, on the Mambilla Plateau (N11°00′–11°30′, E6°30′–7°15′) in Taraba State, Nigeria (Fig. 1). While much of the reserve is savannah scrubland, there is approximately 7.5 km2 of montane/submontane forest (Chapman and Chapman 2001) in two fragments: Ngel Nyaki forest (5.3 km2) and Kurmin Danko (2.2 km2), restricted mainly to steep slopes protected from fire and cattle grazing (Chapman et al. 2004). The forest ranges in altitude from 1,400 to 1,600 m in elevation. The climate has a distinct wet (mid April–late October) and dry season with an average annual rainfall of 1,800 mm (Nigerian Montane Forest Project rainfall data). The Ngel Nyaki chimpanzees are almost entirely isolated from other populations (Knight 2013), are not habituated and are difficult to follow; however, they are vocal and are sometimes heard ‘drumming’, pounding the buttresses of large trees with their fists and feet (Nyanganji et al. 2011).

Food resources commonly (>5 % of the diet/month) consumed by the Ngel Nyaki chimpanzees include Ficus spp. which occur in faeces during 9 months of the year with an annual proportion of 32 % (Dutton and Chapman 2014). When Ficus spp. were not found in faecal samples (during August, September and October), bark, grass, leaves, Vitex doniana, Cordia millenii, Isolona deightonii, and Opilia amentacea were found (Dutton 2013). Dutton and Chapman (2014) observed carpenter ants (Camponotus nr. perrisii) in chimpanzee faeces during 3 months (March, April and June), and stingless bees and beeswax during 1 month each of the year (April and August, respectively).

Data collection and analysis

Data on tool use were collected during reconnaissance and transect walks over a 44-month period from April 2010 to December 2013, for a total of 1,056 days in both dry (October–March) and wet (April–September) seasons during the course of a broader study on the ecology of P. t. ellioti in Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve (Dutton and Chapman 2014; Dutton et al. 2014). As the chimpanzees are not habituated, we were never able to directly observe them making or using tools. All our data are from objects found at ‘tool sites’ accompanied by evidence of chimpanzee presence, such as faeces, hair, dentition marks, foot/hand prints, scent (from undiscovered faeces), nests, remaining dietary items or any combinations of these. If suspected tool sites did not have any evidence of chimpanzee presence they were discarded. We defined tools as being either artefacts or naturefacts (sensu Fowler and Sommer 2007: and references within); that is, they were either tools in the sense that they had been fashioned by the chimpanzees, or unaltered objects used by the chimpanzees to fulfil a particular purpose. We followed the tool nomenclature of Fowler and Sommer (2007) to identify differences and/or similarities of tool types because Gashaka, their study site, is only 25 aerial km from Ngel Nyaki forest.

We measured the lengths and diameters of all stick tools and their ends were categorised into proximal (the end which was closer to the stem, branch or root of the plant from which the tool was removed) and distal (the end furthest from the stem, branch or root of the plant), based on end diameter [wider proximal ends (Fowler and Sommer 2007)] and/or growing direction of (previously stripped) side twigs, buds and/or leaves (directed away from the proximal end). These ends were further placed into one of five categories: sliced; blunt; frayed; pointed and split (after Fowler and Sommer 2007) and measured from the tip to the base of the end (defined as: the last part of the stick to show structural alteration when measured from the tip), running parallel with the stick. In addition we distinguished between frayed ends of ≥30 mm and less than 30 mm in length, because previous work (Sugiyama 1985) has made this distinction and our doing so should allow for future comparative studies. Animal ethics approval criteria (University of Canterbury Animal Ethics Committee, Approval # 2009/26R) disallowed the removal of any tools from the forest, so measurements and evidence could only be made/recorded at the time of discovery.

We compared dimensions (using t-tests) and characteristics (using preliminary data) of tools made by chimpanzees from Ngel Nyaki with those made by chimpanzees from neighbouring Gashaka (recorded by Fowler 2006).

All plant species were identified by consulting the literature (Keay 1990; Chapman and Chapman 2001; Hawthorne and Jongkind 2006), botanists from the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, and the West African Plants Facebook group. We were, however, unable to identify several plant species. We made voucher specimens of all species, which are kept at the Nigerian Montane Forest Project herbarium.

Results

We found 113 individual tools belonging to five tool types at 45 tool-sites over the 44 months (April 2010–December 2013) of opportunistic searches (Table 1). All tools we observed were used for feeding, either on insects (n = 111; four tool types) or fruit (n = 2; two tool types). We found 98 (86.7 %) tools associated with stingless bee (Meliponini) nests (84 digging sticks and 14 probing sticks), 13 (11.5 %) tools associated with the procurement of subterranean Camponotus ants (ten digging sticks and three dipping wands) and two separate tools (1.8 %) associated with the removal of exocarp from two fruit species (Pseudospondias microcarpa and Symphonia globulifera). Apparent tool assemblages (more than one tool type at the same tool-site) were found at tool sites used to collect stingless bee honey and brood, and on two occasions tool assemblages were found at tool sites used to collect ants.

Table 2 illustrates the range of dimensions (whether natural properties of the objects themselves (see Takemoto et al. 2005) or fashioned by the chimpanzees) of the vegetative tools (n = 111) used in insectivory. In 97 % (n = 110) of these tools it was the distal end (farthest away from the plant body) which was used in digging, probing and/or dipping. The proximal end was only used in 54 % of these tools. Fifty-three percent of the tools were used at both proximal and distal ends. All (n = 94) digging sticks were used distally and were typically frayed (Table 2).

While more than 20 plant species were used to make tools, there does not appear to be any consistency in which species were used. Stems of Psychotria peduncularis (a small shrub) showed the highest proportion of use as a tool (23.6 %, n = 26), while stems of the tree Strombosia scheffleri were used 12.7 % (n = 14) as well as the leaf rachis of the tree Carapa oreophila 8.2 % (n = 9).

Tool types

Subterranean stingless bees (Meliponini), species unidentified

Prey species

While stingless bees are common across Africa, species from the Cameroon Highlands remain poorly described (Njoya 2010). The subterranean species found at Ngel Nyaki forest store honey in an underground nest into which lead several entrances concealed under leaf litter (Fig. 2). The entrance tubes are made of wax approximately 8 mm in diameter with 1- to 2-mm-thick walls. The tubes always project upwards directly above the underground nest. Such nests are common (38 nests were discovered in the 44 months of this study) within Ngel Nyaki forest.

Digging sticks (used to dig, perforate and enlarge nest entrances)

We found 26 tool sites with a total number of 84 digging sticks associated with stingless bee subterranean nests (Fig. 3), with up to nine abandoned sticks (mean = 3) of between 6 and 75.5 cm in length (mean = 36.6, SD = 15.3) and 3.0–19.1 mm in diameter (mean = 8.3, SD = 2.7; Table 1). All tools used proximally were also used distally, with all (n = 84) tools used distally and 61 % (n = 51) used proximally. The mean proximal end length (19.9 mm, SD = 25.6) was significantly longer than the distal end length (12.1 mm, SD = 11.8; n (proximal) = 51, n (distal) = 83, U = 1410, z = −3.2352, p = 0.0012). These tools were almost exclusively frayed (97.7 %), with 10.7 % (n = 9) frayed above 30 mm in length, 17.9 % (n = 15) sliced, 2.4 % (n = 2) blunt and 2.4 % (n = 2) split. All tools were stripped of leaves/twigs, most displaying soil contamination, along with 19.0 % (n = 16) completely stripped of bark, 25 % (n = 21) distally stripped and 10.7 % (n = 9) proximally stripped (Table 2). Of the 20 identified plant species used by chimpanzees to construct tools, 16 were used for stingless bee digging sticks (Table 3).

Probing sticks (used to probe nests and extract honey/brood)

Again associated with stingless bee subterranean nests, we found nine tool sites with a total number of 14 probing sticks. We found up to three probing sticks per site (mean = 2, n = 14) ranging from 11 to 73 cm in length (mean = 35.4, SD = 18.8; Fig. 4; Table 1) and 4–13 mm in diameter (mean = 8.8, SD = 2.8; Table 1). Distal ends of tools (n = 14) were always used; however, only 35.7 % (n = 5) of tools showed proximal use. When the proximal end of a tool was used, the distal end was also used. There was no significant difference between the mean proximal end length (29.5 mm) and the mean distal end length (27.6 mm, n (proximal) = 5, n (distal) = 14; U = 32.5, z = −0.1852, p = 0.8493). Although we cannot be certain that these two subterranean stingless bee tool types (digging and probing sticks) had a different function, the differences in wear pattern and their proximity to extracted honey or wax strongly suggest that they differed from the digging sticks. In contrast to the digging sticks, these tools were never frayed but their ends were either sliced (35.7 %, n = 5) or blunt (64.3 %, n = 9; Table 2). They always had all leaves and twigs removed, and 28.6 % (n = 4) were completely stripped of bark. They showed little evidence of soil contamination, often (n = 11) exhibited traces of honey, and/or its odour and on two occasions beeswax. Probing tools were frequently (n = 5) found together with chewed beeswax, which sometimes exhibited chimpanzee dentition (Fig. 3). Seven of the nine tool sites that were discovered also contained two to five digging sticks (mean = 2.3, SD = 1.1). Two tool sites solely contained probing sticks (one probing stick at the first site and two probing sticks at the second site). Seven plant species were used to construct stingless bee probing sticks (Table 3).

Stingless bee tool analysis

The distal and proximal end lengths of stingless bee probing sticks were significantly longer than stingless bee digging sticks (U = 908, z = 3.357, p < 0.0003; U = 199, z = 2.054, p = 0.0399, respectively). There was no significant difference between the diameter (U = 677, z = 0.9036, p = 0.3662), or length (U = 647.5, z = 0.6041, p = 0.5458) of tools used to procure stingless bees.

Subterranean ants, Camponotus nr. perrisii

Prey species

Camponotus nr. perrisii (formerly identified by K.P. Yoriyo, Gombe State University, Nigeria), most commonly subterranean, is the most common ant species evident at Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve (P. Dutton, pers. obs) and was identified in chimpanzee faecal samples during March, April and June (Dutton and Chapman 2014). Army ants, Dorylus, are also present at Ngel Nyaki; they are epigaeic, organizing conspicuous swarm raids on the ground surface (Schöning et al. 2007) and have not been reported in the diet of chimpanzees (Dutton 2013). Nests of C. nr. perrisii appear to be either completely subterranean with only holes in the ground with multiple entrances/exits; or slight mounds (about 30 cm in height and 1 m in diameter) on the ground with one major entrance/exit at the top of the mound. Differences in substrate (e.g. compaction, moisture content, particle size) may determine nest variations (P. Dutton, pers. obs.).

Ant-digging sticks [used to dig and enlarge nest entrances and possibly stir (aggravate) ants]

We assume chimpanzees used ant digging sticks because on two occasions we disturbed chimpanzees, which immediately fled, leaving behind disturbed ant nests with abandoned tools. Some of the tools showed fresh soil contamination and the ant nests showed disturbance which appeared to be the result of digging with the soil-contaminated tools. We found four tool sites with a total number of ten ant-digging sticks associated with C. nr. perrisii ant nests. We found up to three digging sticks per site (mean = 2, n = 10, Fig. 5), ranging from 10 to 102 cm in length (mean = 42.1, SD = 27.8, n = 10) and 6.1–13 mm in diameter (mean = 9.0, SD = 2.0). Distal ends of tools were always (n = 10) used, while only 20 % (n = 2) of tools showed proximal use. The proximal sample size was too small (n = 2) to identify any significant difference between proximal (mean = 10.3 cm, SD = 2.83) and distal end lengths (mean = 24.1 cm, SD = 31.0). All ant digging sticks (n = 10) had frayed ends, were stripped of leaves and twigs, displayed soil contamination, and 30 % were either completely stripped of bark (n = 1), distally stripped of bark (n = 1) or proximally stripped of bark (n = 1). Six plant species were used to construct ant digging sticks (Table 3).

Ant dips (used to procure ants and transport to mouth)

We found two tool sites with two and one ant dips (respectively) associated with C. nr. perrisii ant nests. Ant dips ranged from 32 to 74 cm in length (mean = 57.7, SD = 22.5) and 5–8 mm in diameter (mean = 6.3, SD = 1.5; Fig. 6). Two tools were used only at the distal end and one tool was used only at the proximal end. Proximal and distal end length was similar among the three tools (proximal = 5.1 mm, distal = 3.2 and 6.2 mm). Ant dips differed from ant digging sticks in that they never showed soil-contamination and their ends were either pointed or blunt. Ant dips were always stripped of leaves and side twigs and were either completely stripped of bark (n = 1) or had no bark stripping (n = 2). At one tool site, two ant dips were discovered with three digging sticks, and at the other one ant dip was found with two digging sticks. Two plant species were used to construct ant dips (Table 3).

Ant tool analysis

Ant digging sticks had a significantly wider diameter than ant probing sticks (U = 27, z = 2.0284, p = 0.0425), however, there was no significant difference in length (U = 21, z = 1.0142, p = 0.3105), or tool end length (proximal + distal; U = 30, z = 1.7321, p = 0.0833) between tools used to procure ants.

Food-pound/grate against stone

These tools were observed twice, with a different fruit species on each occasion. On the first occasion, on 04 April 2010, we discovered bunches (approximately ten) and individual immature P. microcarpa fruits (individual fruit dimension: 1 cm width × 2 cm length) scattered along a chimpanzee trail and observed chimpanzee foot and hand prints in disturbed soil. The trail crossed a dried-up stream bed, in which was a boulder (1 m in height, 0.75 m in width, light grey in colour and rough, full of indentations) covered with smashed, scraped, rasped exocarp, mesocarp, juice and resins of P. microcarpa (equivalent to approximately 40 fruits). The ground around the boulder was also littered in mashed fruit. The closest P. microcarpa fruiting tree was at least 100 m away from the boulder and thus circumstantial evidence suggests that the fruit had been carried this distance along the chimpanzee trail before being pressed and scrubbed/rolled/scraped against the boulder to clean the seed of the bitter (senior author, pers. obs.) exocarp and mesocarp before swallowing the seeds. No seeds remained on or around the boulder and after a thorough search (approximately 5 min) no hammers were found with evidence of exocarp or resins/juices, even though appropriate sized stones were readily available. Seeds of P. microcarpa are common in the chimpanzeesʼ faeces at Ngel Nyaki (Dutton 2013).

On the second occasion, on 20 May 2010, we discovered, approximately 150 m off the transect, a group of 16 newly made chimpanzee nests with fresh (<24 h) faecal matter littering the ground. On the ground and directly beneath the nests we discovered a large, partly submerged stone (greatest exposed dimension: 25 cm height × 45 cm width) covered in fresh (<24 h) S. globulifera fruit exocarp (equivalent to approximately 12 fruits; Fig. 7). The sides of the stone were covered in a thick layer of moss, with the arch in the stone showing evidence of disturbance; moss was disturbed and had been rubbed off from the arch in the stone as though it had been used as an anvil on which to pound the S. globulifera (fruit dimensions: 4 cm width × 6 cm length) to release the seeds from the mesocarp which contains bitter latex. Most of the larger pieces of exocarp were damaged (bruising and cracking) and appeared consistent with impact blows with the arch of the rock. There was no evidence in the vicinity (5 m radius) to suggest hammers were used. Fruiting S. globulifera trees were located within a 50-m radius of the stone.

Further analyses of tool measurements

There was no significant difference in the mean length of tools among stingless bee digging sticks (mean = 36.6 cm, SD = 15.3), stingless bee probing sticks (mean = 35.4 cm, SD = 18.8), ant digging sticks [mean = 42.1 cm, SD = 27.8; Kruskal–Wallis: H (adjusted) = 0.843, df = 2, p = 0.6562] and ant dips [mean = 57.7 cm, SD = 22.5; Kruskal–Wallis: H (adjusted) = 3.74, df = 3, p = 0.291, imperfect approximation due to small sample size].

There was no significant difference in the mean diameter of tools among stingless bee digging sticks (mean = 8.3 mm, SD = 2.7), stingless bee probing sticks (mean = 8.8 mm, SD = 2.8), ant digging sticks (mean = 9.0 mm, SD = 2.0; Kruskal–Wallis: H = 1.65, df = 2, p = 0.4382) and ant dips (mean = 6.3 mm, SD = 1.5; Kruskal–Wallis: H = 4.26, df = 3, p = 0.3296, imperfect approximation due to small sample sizes).

Comparison of Ngel Nyaki and Gashaka tool dimensions

We found no significant differences in stingless bee digging stick length (n 1 = 84, n 2 = 9, t = 2.98, df–t = 48.1, p = 0.9976) and diameter (n 1 = 84, n 2 = 9, t = −0.274, df–t = 10.9, p = 0.3915) and stingless bee probing stick length (n 1 = 171, n 2 = 14, t = −0.019, df–t = 14.7, p = 0.4923) between Ngel Nyaki and Gashaka. However, Ngel Nyaki stingless bee probing sticks were significantly wider (n 1 = 172, n 2 = 14, t = −3.094, df–t = 17.1, p = 0.0029) than those at Gashaka. There were no significant differences in ant dipping wand length (n 1 = 72, n 2 = 3, t = 1.95, df–t = 1.8, p = 0.1039) or diameter (n 1 = 71, n 2 = 3, t = 0.063, df–t = 1.6, p = 0.5216) between populations. There was also no difference in length between Ngel Nyaki dipping wands (used for subterranean Camponotus) and Gashaka’s fishing rods (used for arboreal Camponotus; n 1 = 38, n 2 = 3, t = −2.925, df–t = 1.5, p = 0.0508). However, the diameter of Camponotus dipping wands found at Ngel Nyaki were significantly wider than Gashaka’s Camponotus fishing rods (n 1 = 38 n 2 = 3, t = −3.222, df–t = 1.5, p = 0.0428).

Discussion

The small, isolated population of approximately 18 P. t. ellioti individuals in Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve has its own unique tool assemblage with an observed five tool types. Four of these tool types may be part of tool sets, one set for digging and extracting honey and brood from stingless bee subterranean nests (stingless bee digging stick and stingless bee probe) and the other set for the extraction of ants from subterranean nests (ant digging stick and ant dip).

While we did not directly observe the chimpanzees using these tools, we found strong evidence for their use. For example, digging tools that we recovered from sites where chimpanzees had obtained honey from subterranean stingless bee nests had their ends caked in soil, most of them were frayed at one or both ends, their bark was stripped to varying extents and they had no odour of honey. This evidence suggests that these sticks had been used to dig through the soil and enlarge nest entrances (Tutin et al. 1995; Fowler and Sommer 2007). The wax and dentition marks we observed alongside the probes is indicative of these tools being used to determine the presence of honey and brood in the nest, verifying access into the hive, testing the structural integrity of the nest (Sanz and Morgan 2009) and possibly to pry out the honey itself. Tool sites that only contained stingless bee probes (without digging sticks) suggest that either these nests did not require digging because they were easy to access (e.g. nests were not built at great depths, loose soils, thin or soft batumen walls), chimpanzees used their hands to dig, or possibly they removed the digging tools from the site to re-use elsewhere (e.g. Sanz et al. 2010).

The ant digging stick is notable in that tools used for digging after ants have only been reported a few times for catching Dorylus army ants in Bossou, Guinea and in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo (Sugiyama 1995; Sanz et al. 2010; respectively). At Ngel Nyaki the ants were Camponotus nr. perrisii. Moreover, Camponotus spp. at Ngel Nyaki are subterranean, which differs from studies elsewhere where they are arboreal (Nishida and Hiraiwa 1982; Fowler and Sommer 2007; Yamamoto et al. 2011).

Ant dips are most probably used to transport ants from the nest into the mouth (Sugiyamaet al. 1988; Alp 1993). The term ‘ant dipping wand’ has previously been reserved for use with harvesting Dorylus species (see Whiten et al. 2001); however, as described here this term needs to be expanded in its meaning to include Camponotus species, as to our knowledge, they have not been recorded elsewhere. Alternatively a new tool type must be defined such as “Camponotus dip” to distinguish between ant genera.

Our discovery of the food-pound/grate against stone used to remove the skin and pulp from fruits of P. microcarpa and S. globulifera is especially interesting in that this is the first record of this tool type being used in West Central Africa. This technology differs from percussive extractive foraging (such as nut-cracking, baobab-smashing, Strychnos-smashing and pestle-pounding; Koops et al. 2010) in that the food item does not have a hard layer which requires smashing/cracking, but instead has an undesirable exocarp which requires removal. Other examples of non-extractive technology are stone and wooden cleavers, and stone anvils, used by chimpanzees in the Nimba Mountains (Guinea) to fracture large fruits of Treculiaa africana into manageable pieces (Koops et al. 2010). Other records of food being pounded onto stones come from Mahale, Tanzania (Nishida and Uehara 1983); Gombe, Tanzania; the Taϊ forest, Côte d’Ivoire; Assirik, Senegal (Whiten et al. 2001) and Bili, D.R.C. (Hicks 2010). Of relevance to this study is that food-pound/grate stones have not been found in P. t. ellioti populations in Cameroon or neighbouring Gashaka. S. globulifera is relatively common in Gashaka (Dishan et al. 2010) and very likely to be present in Ebo Forest (M. Cheek, pers. comm. 2012) The use of the food pound/grate stones by chimpanzees in Ngel Nyaki most resembles reported behaviour in capuchin monkeys (Sapajus libidinosus) from Fazenda Boa Vista, Brazil. There, the capuchins use two processing techniques (rubbing/piercing and stone tool use) to avoid the caustic chemicals protecting the nutritious kernel of cashew nuts (Sirianni and Visalberghi 2013).

Differences and similarities in tool use between Ngel Nyaki and Gashaka

Of note is that we found both similarities and differences in tools and tool use between the Ngel Nyaki population and the nearby Gashaka population of P. t. ellioti (Fowler 2006), only 25 aerial km away. Similarities included the presence of stingless bee digging and probing sticks, ant dipping wands, absence of termite procuring tools and preferential use of distal ends. Differences included the absence of food pound/grate stones at Gashaka and absence of honeybee tools and ant fish rods (for arboreal Camponotus ants) at Ngel Nyaki.

While analysis of the raw data is necessary for detailed comparisons between the studies, there is a high likelihood that ecological factors contribute to the difference in tools and tool use between these two neighbouring populations. For example, the difference in the selection and consumption of ant species using ant dips is likely a result of species availability (Dorylus at Gashaka versus Camponotus at Ngel Nyaki), likewise the use of ant fishing rods at Gashaka and their absence at Ngel Nyaki may reflect the arboreal nature of Camponotus chrysurus ants at Gashaka (Sommer et al. 2012) and the apparent scarcity of arboreal ants at Ngel Nyaki.

The fact that we found no significant differences in some tool dimensions between Ngel Nyaki and Gashaka (Table 4) but significant differences in others may also have ecological explanations. For example, the fact that the length of stingless bee digging sticks and stingless bee probing sticks were the same in both sites but that stingless bee probing sticks were significantly wider in Ngel Nyaki than in Gashaka might reflect the different structure of stingless bee nest types between the two sites. In Gashaka they are arboreal and subterranean, while at Ngel Nyaki only subterranean nests were observed. Arboreal nests likely require thinner probing tools compared to subterranean nests, as nest entrances are immersed within the tree bark and as a result tend to be thinner. In contrast, digging sticks are used to access subterranean nests at both sites.

Despite the fact that the chimpanzees in each population were eating different ant genera (Ngel Nyaki Camponotus versus Gashaka Dorylus) with different defence strategies [Dorylus (aggressive) and Camponotus (subtle)] we found no significant differences in ant dipping wand length or diameter, presumably because both dipping wands are used on subterranean ant nests; we had predicted that the difference in defence behaviours would select for significantly longer dipping wands used for Dorylus than those used for Camponotus.

There was also no difference in length between Ngel Nyaki dipping wands (used for subterranean Camponotus) and Gashaka’s fishing rods (used for arboreal Camponotus). However, the diameter of Camponotus dipping wands found at Ngel Nyaki were significantly wider than Gashaka’s Camponotus fishing rods which may result from the difference between accessing a subterranean Camponotus nest (Ngel Nyaki) and accessing an arboreal Camponotus nest (Gashaka). Thinner tools may be required to access arboreal ant nests as nest entrances are immersed within the tree bark and as a result tend to be thinner or more restricted than subterranean nests.

The fact that Dorylus ants are present at Ngel Nyaki but the chimpanzees appear to be ignoring them (i.e. no evidence of tool use or remains in their faeces; Dutton 2013) and that Dorylus ants are consumed in great proportions at Gashaka (Pascual-Garrido et al. 2013), may reflect cultural variation. However, these comparisons are speculative as the sample size from Ngel Nyaki is small (Table 4).

Morgan and Abwe (2006) found that P. t. ellioti in Ebo Forest, Cameroon, used hammers and anvils to crack open Coula edulis nuts with combinations of four tools: wooden anvil and wooden hammer, stone hammer and wooden anvil, stone hammer and stone anvil and stone hammer without anvil. None of these behaviours were recorded in either the Gashaka or Ngel Nyaki populations, despite the presence of Elaeis guineensis and Detarium microcarpum nuts in Gashaka (Fowler and Sommer 2007). There have not been any nuts identified at Ngel Nyaki; however, seeds of Carapa ereophila do have similar characteristics (hard outer shell; P. Dutton, pers. obs.) but these have not been identified in the diet of the chimpanzees (Dutton and Chapman 2014). The Ebo Forest population also differs from the Nigerian populations in the use of termite fishing tools. The fact that termite mounds (Macrotermes) are present within both Ngel Nyaki and Gashaka, but no evidence of tools are associated with them may reflect common ecological constraints (such as low abundance of mounds, suitable materials to manufacture tools and termite responsiveness to provocation; Fowler 2006) or a cultural variant (see Fowler and Sommer 2007). Additionally, small termite mounds (about 30 cm high; P. Dutton, pers. obs.) are present outside of the forest but are rare within the forest at Ngel Nyaki (Chapman pers. comm.) with the chimpanzee population seldom venturing outside (P. Dutton pers. obs.) this may reflect both ecological constraints and cultural variation. Tools used by chimpanzees to procure honey from African honeybees (Apis mellifera) have been observed in Gashaka but we found no evidence of such tools at Ngel Nyaki, despite eight encounters with honeybee nests during this study.

Although more research is clearly needed to understand the details of behavioural diversity amongst this population of P. t. ellioti, the current study has made it clear that even nearby populations of the subspecies can differ dramatically in their material culture.

References

Abwe EE, Morgan BJ (2008) The Ebo Forest: four years of preliminary research and conservation of the Nigeria–Cameroon chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes vellerosus). Pan Africa News 15:26–29

Alp R (1993) Meat eating and ant dipping by wild chimpanzees in Sierra Leone. Primates 34:463–468

Boesch C, Boesch H (1990) Tool use and tool making in wild chimpanzees. Folia Primatol 54:86–99

Boesch C, Marchesi P, Marchesi N, Frut B, Joulian F (1994) Is nut cracking in wild chimpanzees a cultural behaviour? J Hum Evol 26:325–338

Boesch C, Head H, Robbins MM (2009) Complex tool sets for honey extraction among chimpanzees in Loango National Park, Gabon. J Hum Evol 56:560–569

Chapman JD, Chapman HM (2001) The forests of Taraba and Adamawa States, Nigeria. An ecological account and plant species checklist. University of Canterbury, Christchurch

Chapman HM, Olsen SM, Trumm D (2004) An assessment of changes in the montane forests of Taraba State, Nigeria, over the past 30 years. Oryx 38:282–290

Dishan EE, Agishi R, Akosim C (2010) Women’s involvement in non timber forest products utilization in support zones of Gashaka Gumti National park. J Res For Wildl Environ 2:73–84

Dutton P (2013) Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes ellioti) ecology in a Nigerian montane forest. Ph.D. thesis. University of Canterbury

Dutton P, Chapman H (2014) Dietary preferences of a submontane population of the rare Nigerian-Cameroon chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes ellioti) in Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve, Nigeria. Am J Primatol. doi:10.1002/ajp.22313

Dutton P, Chapman H, Moltchanova E (2014) Secondary removal of seeds dispersed by chimpanzees in a Nigerian montane forest. Afr J Ecol. doi:10.1111/aje.12138

Fay JM, Carroll RW (1994) Chimpanzee tool use for honey and termite extraction in central Africa. Am J Primatol 33:309–317

Fowler A (2006) Behavioural ecology of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes vellerosus) at Gashaka, Nigeria. Ph.D. thesis. University College London

Fowler A, Sommer V (2007) Subsistence technology in Nigerian chimpanzees. Int J Primatol 28:997–1023

Hawthorne WD, Jongkind CCH (2006) Woody plants of western African forests, a guide to the forest trees, shrubs and lianas from Senegal to Ghana. Kew Publishing, Kew

Hicks TC. 2010 A chimpanzee mega-culture? Exploring behavioral continuity in Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii across northern DR Congo. Dissertation, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Hicks TC, Fouts RS, Fouts DH (2005) Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) tool use in the Ngotto Forest, Central African Republic. Am J Primatol 65:221–237

Humle T (2003) Behaviour and ecology of chimpanzees in West Africa. In: Kormos R, Boesch C, Bakarr MI, Butynski TM (eds) Status survey and conservation action plan: West African chimpanzees. IUCN, Gland, pp 13–19

Humle T (2010) How are army ants shedding new light on culture in chimpanzees. In: Lonsdorf EV, Ross SR, Matsuzawa T (eds) The mind of the chimpanzee: ecological and experimental perspectives. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 116–126

Keay RWJ (1990) Trees of Nigeria. Clarendon Press, New York p 486

Knight A (2013) The genetic structure and dispersal patterns of the Nigeria-Cameroon Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes ellioti). MSc thesis. University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Koops K, McGrew WC, Matsuzawa T (2010) Do chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) use cleavers and anvils to fracture Treculia africana fruits? Preliminary data on a new form of percussive technology. Primates 51:175–178

Matsuzawa T (1994) Field experiments on use of stone tools by chimpanzees in the wild. In: Wrangham RW, McGrew WC, de Wall FBM, Heltne P (eds) Chimpanzee cultures. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 351–370

McGrew WC (1974) Tool use by wild chimpanzees in feeding upon driver ants. J Hum Evol 3:501–508

McGrew WC (1992) Chimpanzee material culture. Implications for human evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Morgan BJ, Abwe EE (2006) Chimpanzees use stone hammers in Cameroon. Curr Biol 16:R632–R633

Nishida T, Hiraiwa M (1982) Natural history of a tool-using behavior by wild chimpanzees in feeding upon wood-boring ants. J Hum Evol 11:73–99

Nishida T, Uehara S (1983) Natural diet of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii): long-term record from the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. Afr Stud Monogr 3:109–130

Njoya MTM (2010) Diversity of stingless bees in Bamenda Afromontane Forests—Cameroon: nest architecture, behaviour and labour calendar. Dissertation, Hohen Landwirtschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn

Nyanganji G, Fowler A, McNamara A, Sommer V (2011) Monkeys and apes as animals and humans: ethno-primatology in Nigeriaʼs Taraba Region. In: Sommer V, Ross C (eds) Primates of Gashaka. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 101–134

Pascual-Garrido A, Umaru B, Allon O, Sommer V (2013) Apes finding ants: predator–prey dynamics in a chimpanzee habitat in Nigeria. Am J Primatol 75:1231–1244

Sanz C, Morgan D (2009) Flexible and persistent tool-using strategies in honey gathering by wild chimpanzees. Int J Primatol 30:411–427

Sanz CM, Morgan D, Gulick S (2004) New insights into chimpanzees, tools, and termites from the Congo Basin. Am Nat 164:567–581

Sanz CM, Schöning C, Morgan DB (2010) Chimpanzees prey on army ants with specialized tool set. Am J Primatol 72:17–24

Schöning C, Ellis D, Fowler A, Sommer V (2007) Army ant prey availability and consumption by Chimpanzees at Gashaka (Nigeria). J Zool 271:125–133

Sirianni G, Visalberghi E (2013) Wild bearded capuchins process cashew nuts without contacting caustic compounds. Am J Primatol 75:387–393

Sommer V, Buba U, Jesus G, Pascual-Garrido A (2012) Till the last drop. Honey gathering in Nigerian chimpanzees. Ecotropica 18:55–64

Sugiyama Y (1985) The brush-stick of chimpanzees found in south-west Cameroon and their cultural characteristics. Primates 26:361–374

Sugiyama Y (1995) Tool-use for catching ants by chimpanzees at Bossou and Monts Nimba, West Africa. Primates 36:193–205

Sugiyama Y, Koman J, Bhoye Sow M (1988) Ant-catching wands of wild chimpanzees at Bossou, Guinea. Folia Primatol 51:56–60

Takemoto H, Hirata S, Sugiyama Y (2005) The formation of the brush-sticks: modification of chimpanzees or the by-product of folding? Primates 46:183–189

Tutin CEG, Ham R, Wrogemann D (1995) Tool use by chimpanzees (Pan t. troglodytes) in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon. Primates 36:181–192

van Schaik CP (2009) Geographical variation in the behavior of wild great apes: is it really cultural? In: Laland KN, Galef BG (eds) The question of animal culture. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp 70–98

Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin CEG, Wrangham RW, Boesch C (1999) Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature 399:682–685

Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin CEG, Wrangham RW, Boesch C (2001) Charting cultural variation in chimpanzees. Behaviour 138:1481–1516

Yamamoto S, Yamakoshi G, Humle T, Matsuzawa T (2011) Ant fishing in trees: invention and modification of a new tool-use behavior. In: Matsuzawa T, Humle T, Sugiyama Y (eds) The Chimpanzees of Bossou and Nimba. Springer, Japan, pp 123–130

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Taraba State Forestry for logistical support and the Nigerian Montane Forest Project for field facilities and field assistance, especially to Alfred Moses and Suleiman A. Idi. Funding was from the North of England Zoological Society (Chester Zoo), Nexen Inc., A. G. Leventis Foundation and Primate Conservation Inc. (PCI).

The sampling protocol used in this study complied with the ethical standards in the treatment of animals with the guidelines laid down by the Primate Society of Japan, NIH (US), EC Guide for animal experiments, was approved by the University of Canterbury Animal Ethics Committee, Approval # 2009/26R and was in compliance with the laws governing animal research in Nigeria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Dutton, P., Chapman, H. New tools suggest local variation in tool use by a montane community of the rare Nigeria–Cameroon chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes ellioti, in Nigeria. Primates 56, 89–100 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-014-0451-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-014-0451-1