Abstract

Self-regulated learning is recognized as a core competence for academic success and life-long formation. The social context in which self-regulated learning develops and takes place is attracting growing interest. Using cross-sectional data from secondary education students (n = 561), we aimed to formulate explanatory arguments regarding the effect of social support on metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies, and academic achievement, considering the potential mediating role of goal orientation self-management. Structural Equation Modelling yielded a conceptually consistent and statistically satisfactory empirical model, explaining a moderate-high percentage of the variance in self-regulated learning and academic achievement. The results showed that perceived support from teachers and family positively predicted metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies, and mastery self-talk and negatively predicted work-avoidance self-talk. Moreover, mastery self-talk and work-avoidance self-talk directly and indirectly (through metacognitive knowledge) predicted academic achievement. Perceived social support is proposed as a marker of vulnerability/protection and as a resource for facing challenges in the academic context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The construct of self-regulated learning has generated increasing interest over the last three decades due to its heuristic value, enabling academic learning to be modelled and inspiring educators who seek to understand how students become engaged and autonomous (Huang et al., 2023; Schunk & Greene, 2018). Self-regulated learning is defined as a process of activating and sustaining cognitions, affects, and actions, when students address learning objectives in interaction with environmental factors. It is conceived as a self-directed process that is started and sustained by metacognition, which comprises metacognitive knowledge (MK) and control of one’s thinking (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2013; Zeidner & Stoeger, 2019). Metacognitive knowledge consists of ideas and beliefs about the self as a learner (declarative), about how to perform learning strategies (procedural) and about when and why to use them (conditional) (Efklides, 2017). On the other hand, metacognitive control entails self-awareness of and access to learning strategies, which comprise metacognitive (planning, monitoring, reviewing, and evaluating), cognitive (rehearsal, elaboration, and organization), and motivational (focusing attention, and maintaining self-motivation) learning strategies (Zeidner & Stoeger, 2019). These types of skills conform a basic competence which is considered a key to academic success and life-long learning (OECD, 2018). Research studies involving diverse educational levels and situations have consistently found that self-regulated learning is positively associated with academic engagement (Cleary et al., 2020; Li & Lajoie, 2022), adjustment (De la Fuente et al., 2020; García-Ros et al., 2022), and achievement (De la Fuente et al., 2020; Dent & Koenka, 2016; Mega et al., 2014).

Since the earliest theoretical models of self-regulated learning appeared, environmental conditions have been perceived as having a key influence on development and implementation of metacognitive knowledge and skills (Panadero, 2017; Puustinen & Puulkinen, 2001). Special emphasis has been placed on social support, which is considered the basis for enhancement of inner motivational resources (i.e. motivational self-regulation), which will, in turn, favour self-regulated learning (Perry et al., 2018; Skinner et al., 2008). Recent theoretical proposals specifically highlight self-management of academic goals as a manifestation of motivational self-regulation (Miele & Scholer, 2018; Wolters, 2003). The supposed relationships between these dimensions are described in the following sections.

The influence of social support on self-regulated learning

Several theoretical models of self-regulated learning have highlighted the role of social environmental influences. Thus, for instance, Ben-Eliyahu and Bernacki (2015) have drawn attention to the ecology of factors that affect learning. These authors sustain that academic engagement may not only be conditioned by the immediate academic environment of the classroom, but also by other microsystems (i.e. family, teachers, peers) and distal systems (e.g. cultural values, social conditions). In fact, primary socializing contexts are thought to determine the development of self-regulated learning, and in particular motivational self-regulation, through social influence processes such as modelling, scaffolding, and direct instruction (Wolters, 2011; Zimmerman & Schunk, 2012). At the same time, according to the Self-Determination Theory (SDT, Ryan & Deci, 2002), insofar as those contexts fulfil basic psychological needs (competence, autonomy, and relatedness), they will foster or undermine self-regulation by modulating the internalization and integration of interests and goals (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Stroet et al., 2013).

Supportive relationships with family, teachers, and peers are considered essential, both as a condition to fulfil basic needs and as a guidance resource for the development of learning strategies (Danielsen et al., 2011; Stroet et al., 2013). According to the Self-System Model of Motivational Development (SSMMD; Newman, 2000; Skinner et al., 2008), the need for competence should be fulfilled by a supportive social context that provides structure (i.e. information on desired outcomes), while the need for autonomy should be satisfied by supplying confidence in students’ abilities, and the need for relatedness should be met by provision of involvement. In general, perceived social support is thought to moderate the appraisal of situations as threatening and to enhance self-confidence to cope with new challenges (Cohen et al., 2000; Schwarzer & Knoll, 2007). The effect of peer support, however, is considered to be more uncertain, as it has been associated with both positive and negative manifestations (Rueger et al., 2008; Worley et al., 2023).

Self-regulated learning, motivational self-regulation, and goal oriented self-talk as a principal motivational strategy

As already mentioned, learning strategies are classified into metacognitive, cognitive, and motivational strategies. Metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies (MCLS) have prevailed in research on self-regulated learning, although the motivational facet is increasingly being considered (Bakhtiar & Hadwin, 2021). This facet is now emphasized as a core part of self-regulation, as it may affect the intention to learn and the effort and persistence during the learning process, as well as learning strategies and academic achievement (Wolters, 2003). This entails viewing motivation from an agentic perspective. Thus, although the essential role played by a motivational learning climate is generally recognized, some authors have indicated that teaching students to regulate their own motivation may be more effective for promoting self-regulated learning (Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006; Miele & Scholer, 2016).

Among the first theoretical approaches to motivational self-regulation, the structural model developed by Boekaerts (1996, 1999) deserves to be highlighted. This author distinguished between two interrelated regulatory systems, one of which was referred to as information processing and the other as emotional-motivational management. Boekaerts and colleagues (Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006; Boekaerts & Niemivirta, 2000) later developed a dual processing self-regulation model and adopted a dynamic perspective in which two alternative processing paths were proposed (mastery/growth vs. coping/ well-being). The first path would be taken by the student when pursuing self-chosen learning goals, in line with personal interests and values, while the second path implies prioritising ego-protective goals when confronting failure, coercion, or competing goals or when the learner is unwilling to invest energy in a task.

More recently, the metamotivational model of motivation regulation posited by Miele and Scholer (2016, 2018) delimited different procedures that individuals might use to manage one’s own motivation inner speech aimed at reminding oneself of the reasons for engaging in a task is emphasized in the model. Specifically, mastery self-talk focuses on developing one’s interests or improving one’s personal skills and abilities; on the other hand, performance self-talk focuses on gaining/maintain good grades (self-enhancing), demonstrating one’s competence or avoiding looking incompetent to others (self-defeating).

Goal setting and striving are central to the self-regulated learning construct, and there is some evidence that mastery goals are generally better attuned to self-regulation than performance goals. Thus, mastery-oriented students are more likely to experience positive academic emotions (Schweder, 2020), to self-monitor (Cellar et al., 2011) and to use MCLS (Merett et al., 2020), ultimately favouring persistence and achievement (Sideridis & Kaplan, 2011; Wood et al., 2013). The relationship between the performance-orientation tendency and self-regulated learning seems to depend on whether the main underlying concern of the student is to demonstrate their capability (self-enhancing) or to avoid being evaluated negatively (self-defeating), with the first option being better adapted to self-regulation (Brdar et al., 2006). On the other hand, work-avoidance orientation, which consists of the intention to invest the minimum effort in academic tasks, has been described (King & McInerney, 2014; Mendoza & Ronnel, 2022). It is thought to characterize students disaffected with school (bored, passive), and to be caused by feelings of incompetence, low task-value beliefs or low sense of control to meet achievement goals (Jarvis & Seifert, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2002). It has also been negatively associated with MCLS and academic achievement (Brdar et al., 2006; Suárez-Riveiro et al., 2001; Takashiro, 2016).

Some evidence has already been produced with respect to goal-directed self-talk (GDST) as a strategy for motivational self-regulation, although more investigation is clearly needed. Mastery and performance self-talk strategies have been shown to positively predict academic engagement (Smit et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017), MCLS (Suárez-Riveiro et al., 2016; Wang, 2013), effort, and academic achievement (Kryshko et al., 2020; Schwinger & Otterpohl, 2017; Smit et al., 2017), while work-avoidance self-talk has been negatively related to MCLS (Suárez-Riveiro et al., 2016).

Perceived social support, at least from parents and teachers, may be expected to affect the balance between growth and well-being paths described in the dual processing self-regulation model and also the adoption of motivational strategies focused on reinforcing mastery or performance orientation. The motivational inclination of an individual may, in turn, affect cognitive and metacognitive self-regulation. However, the relationship between perceived social support and self-regulated learning remains unexplored, and the interplay between metacognitive, cognitive, and motivational areas of self-regulated learning should also be analysed further. In this respect, exploring a normative, age-related transitional period such as early adolescence deserves special attention, given that self-regulated learning skills and social support resources may help adolescents to cope better with the stress produced by new challenges faced at school (Anderson et al., 2000; Evans et al., 2018).

The present study

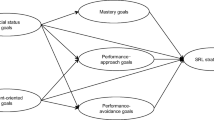

The present study considers the role of perceived social support from teachers, family, and friends on self-regulated learning (MK, MCLS, and GDST) and academic achievement and the relationships between MK, MCLS, and GDST. These relationships are addressed at a global level, i.e. in terms of tendencies manifested across learning episodes. The conceptual model is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the following hypotheses were established:

-

H1. Perceived social support from teachers, family, and friends is associated with academic achievement, and a mediational effect of self-regulated learning (metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive, cognitive, and motivational learning strategies) on this association is also expected.

-

H2. Goal-directed self-talk predicts metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies.

Method

Participants

The study sample consisted of 561 students (56.1% females), aged between 12 and 15 years (M = 13.46; SD = 1.08), enrolled in secondary school academic courses (Grade 7, 25.8%; Grade 8, 21.2%; Grade 9, 33.3%; Grade 10, 19.6%) and recruited from various state schools in Galicia (Spain), situated in regions characterized by different degrees of urbanization (European Commission, 2014).

Measures

Perceived support from teachers was evaluated by several items of the Spanish version of Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC; Moreno et al., 2014). HBSC is a collaborative international World Health Organization survey that collects data on the health and well-being of students aged 11, 13, and 15 years. The questionnaire has seven items, with a 5-point Likert-type scale response format, designed to assess the student’s perception that teachers care for and value them (e.g. “My teachers are interested in me as a person” and “My teachers give me extra help when I need it”). The HBSC has demonstrated reliability and validity across diverse adolescent samples (Bi et al., 2021; Currie & Morgan, 2020; Danielsen et al., 2011). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.86.

Perceived support from family and friends was assessed with the Spanish version of The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1988) adapted by Landeta and Calvete (2002). The scale includes eight items, with 6 Likert-type points, which explore the extent to which students perceive that family (4 items) or friends (4 items) would be available to them when needed (e.g. “I can talk about my problems with my family” and “My friends really try to help me”). The MSPSS has shown good reliability and validity with adolescent students (Bi et al., 2021). The Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were high for both scales (α = 0.89).

Goal-directed self-talk was evaluated with the self-Regulation of Achievement Goals subscale of the Escalas de Estrategias Motivacionales del Aprendizaje-Versión Secundaria (EEMA-VS; Suárez-Riveiro & Fernández-Suárez, 2011). This subscale consists of 18 items, with 5 Likert-type points, designed to measure four types of strategies aimed at regulating achievement goals: mastery self-talk (5 items, e.g. “Before starting a complicated task, I usually think about how interesting it might be”), self-enhancement (5 items, e.g. “I set myself the goal to do my homework better than anyone else”), self-defeating (4 items, e.g. “When I participate in class, I consider avoiding to appear not capable to my classmates”), and work-avoidance (4 items, e.g. “I usually plan to work as little as possible in class or at home”). The reliability and validity of the scale have been established in previous studies (Suárez-Riveiro et al., 2016; Suárez-Riveiro & Fernández-Suárez, 2011). The Cronbach’s alpha for the sub-scales ranged between 0.82 and 0.89.

Metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies were assessed with the Spanish version of the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI; Schraw & Dennison, 1994) adapted by Huertas et al. (2014). The scale has fifty-two items, with 5 Likert-type points, distributed in two categories: MK (17 items) and MCLS (35 items). The first includes declarative knowledge (e.g. “I learn more when I am interested in the topic”), procedural knowledge (e.g. “I am aware of what strategies I use when I study”), and conditional knowledge (e.g. “I can motivate myself to learn when I need to”). The second includes five subprocesses: planning (e.g. “I think of several ways to solve a problem and choose the best one”), monitoring (e.g. “I find myself analysing the usefulness of strategies while I study”), reviewing (e.g. “I stop and go back over new information that is not clear”), evaluating (e.g. “I ask myself if I learned as much as I could have once I finish a task”), and cognitive strategies (e.g. “I use the organizational structure of the text to help me learn”). Huertas et al. (2014) showed that MAI is a reliable, valid instrument for measuring adolescents’ MK and MCLS. The Cronbach’s alpha values for subscales were 0.88 and 0.92, respectively.

Students’ academic achievement was measured by the grade-point average (GPA), obtained from official school records. Official grades in Spanish schools are scored from 0 to 10, with a pass mark of 5.

An academic and sociodemographic questionnaire was administered to collect information about students’ sex, age, academic courses, school, repeated courses, additional educational needs, and parental education level.

Procedure

An ex post facto prospective design with more than a causal link was applied. This type of design enables the assessment of the direct and indirect influences of a set of independent variables on a dependent variable, for a unique group of participants.

The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study and the data collection procedure. The participating educational centres were selected by convenience sampling. All accessible subjects in the sample were surveyed. As the participants were minors, their family or legal tutors were informed about the purpose of the study and were asked to sign an informed consent permitting their children to participate in the study. Data were collected by two members of the research team during the first trimester of the school year, with the prior permission and consent of students, families, teachers, and schools, according to the APA Ethics Code Standards (APA, 2017) and the Declaration of Helsinki. The students were informed that participation in the study was voluntary, and the data was treated confidentially. Questionnaires about perceived social support and self-regulated learning were administrated collectively by researchers in the classrooms during the normal academic schedule; assessments lasted approximately 30 min. Students’ academic grades were obtained from school records at the end of the first trimester of the school year.

Data analysis

The hypothesised relationships between perceived social support, self-regulated learning, and academic achievement were analysed by Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), implemented with IBM AMOS 21. Model fit was evaluated using various criteria including the chi-square test, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardized root mean residual (SRMR), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI). The fit was considered good when it fulfilled the following criteria: RMSEA and SRMR both < 0.08, CFI and GFI both > 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1995). Bootstrapping was used to calculate the 90% confidence intervals of path coefficients. There were no missing data for the variables included in the model.

Results

Preliminary analysis

The first step in handling the data was to perform descriptive analysis. The mean values, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and Cronbach alpha coefficients of the measurements used in this research are shown in Table 1. Appropriate asymmetry indexes and kurtosis and acceptable coefficients of reliability were obtained for all of the variables. The Mardia’s Kurtosis Index was 24.21, indicating that the distance from multivariate normality was not critical for the analysis (Rodríguez-Ayán & Ruiz, 2008).

The next step was to carry out bivariate correlation analysis (Pearson’s r) to verify the magnitude of the relationship between the variables included in the conceptual model (Fig. 1). Significant correlations between variables varied from −0.42 to 0.73, at significance levels of p ≤ .05 and p ≤ .01 (Table 1).

Hierarchical regression analysis was then performed to assess the relative contribution of each source of support to self-regulated learning and academic achievement, as well as possible mediational effects. Therefore, the assumptions for multivariate analysis were first assessed by checking the linearity, collinearity, homoscedasticity, normality, and interdependence between residues. The hierarchical regression analysis (R2 = 0.19, F (15,545) = 9.53, p ≤ .000) showed that support from family and friends did not significantly affect academic achievement. Nevertheless, on the basis of the theoretical framework described in the introduction and the observed correlations between family support and dimensions of self-regulated learning, only support from friends was omitted from the model tested.

Structural models

The model of the relationships between perceived support from family and teachers, self-regulated learning, and academic achievement was examined using path analysis, by applying the maximum likelihood estimation method.

Goodness-of-fit measures showed that the proposed model produced a poor fit to the data (X2(df) = 809.37 (69), p ≤ .000; GFI = 0.83; CFI = 0.85; RMSEA = 0.14; SRMR = 0.15). Several of the model path coefficients were low and non-significant (p > .05). Additionally, modification indices suggested covariance between perceived support from family and teachers and an effect of MK on MCLS. Considering these data, and in accordance with the underlying theoretical framework, a decision was therefore taken to re-specify the model, removing all non-significant paths and including the perceived social support covariance and the effect of MK on MCLS. The final model is shown in Fig. 2.

After modification of the model, the goodness-of-fit measures indicated a satisfactory fit to the data (X2(df) = 183.4 (54), p ≤ .000; GFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.07 (CI 90% = 0.06–0.08); SRMR = 0.03). All of the model path coefficients were statistically significant (Table 2). The effect size of the determination coefficients was obtained using Cohen´s f2 coefficient (Cohen, 1992), taking into account the following critical values: f2 = 0.02 small; f2 = 0.15 medium; and f2 = 0.35 high. The effect size for personal variables of mastery self-talk (f2 = 0.28), word-avoidance self-talk (f2 = 0.28), MK (f2 = 0.82), MCLS (f2 = 4.88), and academic achievement (f2 = 0.19) was medium to high. These results show that the relationships between perceived support from family and teachers and mastery and work-avoidance self-talk explained 16% of the variance in academic achievement, 83% of the variance in MCLS, and 45% of the variance in MK.

The total, direct, and indirect effects of the variables included in the model were analysed. The bootstrap method (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993) was used to determine confidence intervals (CIs) and the significance of total, direct, and indirect effects, by estimating confidence intervals corrected to 90% and with 2000 samples chosen at random from the data. The results of these analysis are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

The main goal of the present study was to develop an explanatory model of the influence of significant others as sources of support in self-regulated learning, and ultimately in academic achievement in secondary school students. On the basis of the theoretical framework and preliminary statistical analysis, an empirical model that included support from teachers and from family as independent variables was tested. This model presented adequate fit indexes and significant direct and indirect relationships, with medium to high size effects.

In general terms, we observed the expected relationships between perceived social support, self-regulated learning, and academic achievement. In line with hypothesis 1, a significant direct effect of support from teachers on academic achievement was observed, a finding that is consistent with those of previous studies (An et al., 2022; Lee & Simpkins, 2021). As already indicated by Stiller and Ryan (1992), support from teachers, as principal representatives of the academic context, unsurprisingly affected learning outcomes. Teachers are the main providers of information and opportunities for the students to acquire necessary disciplinary knowledge and skills to adapt to a changing world, particularly in relation to learning-to-learn and self-regulation (OECD, 2018). This commitment should lead to pupil’s perceived structure (i.e. expectations, feedback), which would be expected to fulfil their need for competence, one of the basic psychological needs, as regarded by the Self-Determination Theory (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Newman, 2000; Stroet et al., 2013). Through supplying clear information about how to effectively achieve desired outcomes, teachers can improve metacognitive knowledge and awareness regarding learning strategies and oneself as a learner. In accordance with this assumption, we have demonstrated a positive predictive effect of perceived support from teachers on MK and MCLS and a mediating effect of MK on the relationship between support and MCLS and the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement. Studies carried out to date on the relationship between perceived social support and self-regulated learning have concentrated on MCLS, consistently confirming that support from teachers positively predicts strategic learning (McEown & McEown, 2018; Yildirim, 2012) and that this effect mediates the relationship between perceived support and achievement (Jelas et al., 2016; King & Ganotice, 2014). Our data suggest that, as expected, MK plays a central role in the variability in achievement explained by MCLS.

Teachers can also fulfil students’ need for autonomy and relatedness (the other basic psychological needs), as long as they enable personal choices and interests and foster feelings of emotional security and closeness (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Marchand & Skinner, 2007). Students who perceive autonomy support from their teachers are expected to exhibit more internalized motivation, so that the student’s behaviour will comply with personal interests or values, and will have an internal perceived locus of causality and will be experienced as volitional (Reeve et al., 2008). On the other hand, perceived involvement support from teachers is expected to contribute to students’ general feelings of self-worth, favouring adoption of a mastery processing path and affecting both self-regulation of achievement goals, MK, and MCLS, as assumed in the dual processing self-regulation model (Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006; Boekaerts & Niemivirta, 2000) and the metamotivational model of motivation regulation (Miele & Scholer, 2016, 2018). Our findings are consistent with these ideas, showing that perceived support from teachers positively predicted mastery self-talk and negatively predicted work-avoidance self-talk; moreover, these effects mediated the relationship between perceived support from teachers and MK and MCLS. Nevertheless, no relationship between perceived support from teachers and performance self-talk was observed, which suggests that student’s use of this type of strategy may vary depending on the level of challenge, competitive pressure, and perceived support in particular learning episodes; such variation has previously been demonstrated in relation to goal orientations (Elliot et al., 2005; Yeo et al., 2009).

Regarding family support, its direct predictive value of family support on achievement was not significant, although indirect effects were observed through GDST and MK. Previous studies have reported a significant direct effect of parental support on the academic achievement of secondary school students (Ferraces et al., 2020; Jiang et al, 2011; Lam et al., 2012). In the present study, asking participants globally about the family as a source of support and jointly assessing the MCLS of participants may have blurred the principal and multifaceted role of family in promoting and monitoring academic outcomes. More investigation is clearly needed on this issue.

We found that the effect of perceived support from family on self-regulated learning was also in the expected direction. We observed a positive effect of this source of support for MCLS, which is consistent with previous observations (Choe, 2020; Monroy et al., 2019; Won & Yu, 2018). We also demonstrated a positive effect of perceived support from family on MK and mastery self-talk and a negative effect on work-avoidance self-talk. No previous data are available on these effects. From a theoretical perspective, diverse functions performed by the family may favour self-regulated learning by fulfilling basic psychological needs. Indeed, regarding the structure facet of support, parental modelling, reinforcement, and instruction about student homework is consistently recognized (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2001). Family are also assumed to provide support for autonomy by tailoring a suitable general environment in which their children can feel responsible for their own actions, fostering autonomous self-regulation in general (Soenens et al., 2007) as well as involvement support by responding sensitively, with warmth and acceptance (La Guardia et al., 2000). In the light of our results, replicate studies considering the role of different parental support resources would be valuable to clarify processes underlying the adoption of different forms of goal-directed self-talk as strategy for regulating motivation, as well as the effect of this and other types of motivational strategies on MK and MCLS.

Finally, the effect of perceived support from friends on academic achievement was not statistically significant, although the correlations indicated the expected direction of the relationship. Perceived support from peers has previously been shown to predict academic achievement, both directly and through MCLS (Jelas et al., 2016; King & Ganotice, 2014; Song et al., 2015). Perhaps, as suggested by Rueger et al. (2008), we may expect different levels and outcomes of perceived support when close relationships such as friendships are considered, as in the present study. Furthermore, friendship is particularly important during adolescence, probably determining increased attention to social goals (intimacy, complicity, sharing joy), while support from classmates may be perceived as being more closely connected to academic goals.

Regarding the role of motivational self-regulation on the proposed model, the trends in the data obtained in the present study are also as expected from the proposed hypothesis. More precisely, mastery self-talk directly and positively predicted MK and MCLS and indirectly predicted academic achievement through MK. On the other hand, work-avoidance self-talk directly and indirectly (through MK) negatively predicted academic achievement. Neither self-enhancing nor self-defeating strategies contributed to the model tested, although the latter strategy was significantly negatively correlated with academic achievement. Thus, our results are consistent with the assumption that mastery self-talk activates MK and gives rise to MCLS, which in turn would favour academic achievement, while work-avoidance self-talk would hinder academic engagement and achievement. The relationships between self-enhancing and self-defeating strategies and self-regulated learning and achievement should be further analysed. Previous data on the relationship between GDST and MCLS suggest that it depends on the specific type of strategy being examined (Suárez-Riveiro et al., 2016); this also seems to apply to the relationships between MCLS and academic achievement (Dent & Koenka, 2016).

In summary, our results highlight the importance of perceived social support both from teachers and family as regards adoption of adaptive/maladaptive forms of motivational self-regulation, as well as a mediating effect of motivational strategies being prioritised by the student on MK and MCLS, with repercussions for academic achievement. A global image of the interplay between perceived social support, self-regulated learning, and achievement is provided that may serve as basis for a more domain-specific or state-dependent exploration of learning in context.

Some limitations of the study must be considered. First, all variables—except academic achievement—were measured through self-reports. Although these variables are considered reliable and suitable for measuring self-regulated learning and perceived social support, they are not exempt from subjective bias (e.g. social desirability). Second, our analysis was based on cross-sectional data, and therefore neither definitive causal nor directional conclusions should be drawn. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to establish causal relationships and their direction. Future research should also explore further the effect of different sources (e.g. family and teachers), as well as specific types of support resources, on the knowledge and use of specific learning strategies.

Conclusion

The study findings add to current scientific knowledge by establishing explanatory links between social support from family and teachers, self-regulated learning, and academic achievement, considering the moderating role of MK and GDST in secondary students. Current findings suggest that perceived social support may serve as a marker of vulnerability/protection in regard to the challenges typically faced by adolescents in their transition to secondary school as well as of the difficulties/potential for self-regulation and academic achievement. Moreover, the findings may lay the foundations for outlining guidelines and intervention programs aimed at favouring adjustment of adolescents in the educational system, providing them with the skills to respond to the growing training demands of the so-called “knowledge and lifelong learning society” and helping to mitigate the difficulties that may hinder vocational development and social integration. Based on the study findings, the inclusion of social support as a dimension of programs aimed at training learning skills is expected to enhance the effectiveness of such programs; this is, in fact, indicated by some intervention studies that have focused on the way in which support contributes to the individual’s basic needs and fosters social integration. Improvement of perceived social support and self-regulation skills is contemplated a priori as an adequate strategy favouring academic progress.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Retrieved Oct 2, 2023, from https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

An, F., Yu, J., & Xi, L. (2022). Relations between perceived teacher support and academic achievement: Positive emotions and learning engagement as mediators. Current Psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03668-w

Anderson, L. W., Jacobs, J., Schramm, S., & Splittgerber, F. (2000). School transitions: Beginning of the end or a new beginning? International Journal of Educational Research, 33, 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(00)00020-3

Bakhtiar, A., & Hadwin, A. F. (2021). Motivation from a self-regulated learning perspective: Application to school psychology. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/08295735211054699

Ben-Eliyahu, A., & Bernacki, M. L. (2015). Addressing complexities in self-regulated learning: A focus on contextual factors, contingencies, and dynamic relations. Metacognition Learning, 10, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-015-9134-6

Bi, S., Stevens, G. W., Maes, M., Boer, M., Delaruelle, K., Eriksson, C., Brooks, F. M., Tesler, R., van der Schuur, W. A., & Finkenauer, C. (2021). Perceived social support from different sources and adolescent life satisfaction across 42 countries/regions: The moderating role of national-level generalized trust. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 1384–1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01441-z

Boekaerts, M. (1996). Personality and the psychology of learning. European Journal of Personality, 10, 377–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0984(199612)10:5<377::AID-PER261>3.0.CO;2-N

Boekaerts, M. (1999). Self-regulated learning: Where we are today. International Journal of Educational Research, 31, 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00014-2

Boekaerts, M., & Cascallar, E. (2006). How far have we moved toward the integration of theory and practice in self-regulation? Educational Psychology Review, 18(3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9013-4

Boekaerts, M., & Niemivirta, M. (2000). Self-regulated learning: Finding a balance between learning goals and ego-protective goals. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 417–450). Elsevier.

Brdar, I., Rijavec, M., & Loncaric, D. (2006). Goal orientations, coping with school failure and school achievement. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173569

Cellar, D. F., Stuhlmacher, A. F., Young, S. K., Fisher, D. M., Adair, C. K., Haynes, S., Twichell, E., Arnold, K. A., Royer, K., Denning, B. L., & Riester, D. (2011). Trait goal orientation, self-regulation, and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(4), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9201-6

Choe, D. (2020). Parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of parental support as predictors of adolescents’ academic achievement and self-regulated learning. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105172

Cleary, T. J., Slemp, J., & Pawlo, E. R. (2020). Linking student self-regulated learning profiles to achievement and engagement in mathematics. Psychology in the Schools, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22456

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

Cohen, S., Gottlieb, B. H., & Underwood, L. G. (2000). Social relationships and health. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention (pp. 3–23). Oxford University Press.

Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In M. R. Gunnar & L. A. Sroufe (Eds.), Self-processes and development (Vol. 23, pp. 43-77). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Currie, C., & Morgan, A. (2020). A bio-ecological framing of evidence on the determinants of adolescent mental health-a scoping review of the international Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study 1983-2020. SSM-Population Health, 100697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100697

Danielsen, A. G., Breivik, K., & Wold, B. (2011). Do perceived academic competence and school satisfaction mediate the relationships between perceived support provided by teachers and classmates, and academic initiative? Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(4), 379–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.587322

De la Fuente, J., Amate, J., González-Torres, M. C., Artuch, R., García-Torrecillas, J. M., & Fadda, S. (2020). Effects of levels of self-regulation and regulatory teaching on strategies for coping with academic stress in undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00022

Dent, A. L., & Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 425–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Efklides, A. (2017). Affect, epistemic emotions, metacognition, and self-regulated learning. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 119(13), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811711901302

Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. Champan & Hall.

Elliot, A. J., Shell, M. M., Henry, K. B., & Maier, M. A. (2005). Achievement goals, performance contingencies, and performance attainment: An experimental test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(4), 630–640. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.4.630

European Commission. (2014). A harmonised definition of cities and rural areas: The new degree of urbanisation. Retrieved Oct 2, 2023, from https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/working-papers/2014/a-harmonised-definition-of-cities-and-rural-areas-the-new-degree-of-urbanisation

Evans, D., Borriello, G. A., & Field, A. P. (2018). A review of the academic and psychological impact of the transition to secondary education. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01482

Ferraces, M. J., Lorenzo, M., Godás, A., & Santos, M. A. (2020). Students’ mediator variables in the relationship between family involvement and academic performance: Effects of the styles of involvement. Psicología Educativa. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2020a19

García-Ros, R., Pérez-González, F., Tomás, J. M., & Sancho, P. (2022). Effects of self-regulated learning and procrastination on academic stress, subjective well-being, and academic achievement in secondary education. Current Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03759-8

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. C., Walker, J. M. T., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 2001(36), 3.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modelling: Concepts, issues and applications (pp. 76–99). Sage.

Huang, L., Zhou, J., Wang, D., Wang, F., Liu, J., Shi, D., Chen, X., Yang, D., & Pan, Q. (2023). Visualization analysis of global self-regulated learning status, hotspots, and future trends based on knowledge graph. Sustainability, 15, 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032798

Huertas, A. P., Vesga, G. J., & Galindo, M. (2014). Validación del instrumento ‘inventario de habilidades metacognitivas (MAI) con estudiantes colombianos. Revista de Investigación y Pedagogía, 5(10), 55–74.

Jarvis, S., & Seifert, T. (2002). Work avoidance as a manifestation of hostility, helplessness, and boredom. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 48(2), 174–118. https://doi.org/10.11575/ajer.v48i2.54921

Jelas, Z. M., Azman, N., Zulnaidi, H., & Ahmad, N. A. (2016). Learning support and academic achievement among Malaysian adolescents: The mediating role of student engagement. Learning Environments Research, 19(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-015-9202-5

Jiang, Y. H., Yau, J., Bonner, P., & Chiang, L. (2011). The role of perceived parental autonomy support in academic achievement of Asian and Latin American adolescents. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9(2), 497–522.

King, R. B., & Ganotice, F. A. (2014). The social underpinnings of motivation and achievement: Investigating the role of parents, teachers, and peers on academic outcomes. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0148-z

King, R. B., & McInerney, D. M. (2014). The work avoidance goal construct: Examining its structure, antecedents, and consequences. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39, 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.12.002

Kryshko, O., Fleischer, J., Waldeyer, J., Wirth, J., & Leutner, D. (2020). Do motivational regulation strategies contribute to university students’ academic success? Learning and Individual Differences, 82, 101912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101912

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-etermination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367

Lam, S., Lam, S., Kikas, E., Cefai, C., Veiga, F. H., Nelson, B., Hatzichristou, C., Polychroni, F., Basnett, J., Duck, R., Farrell, P., Liu, Y., Negovan, V., Shin, H., Stanculescu, E., Wong, B. P. H., Yang, H., & Zollneritsch, J. (2012). Do girls and boys perceive themselves as equally engaged in school? The results of an international study from 12 countries. Journal of School Psychology, 50, 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.07.004

Landeta, O., & Calvete, E. (2002). Adaptación y validación de la Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido. Ansiedad y Estrés, 8, 173–182.

Lee, G., & Simpkins, S. D. (2021). Ability self-concepts and parental support may protect adolescents when they experience low support from their math teachers. Journal of Adolescence, 88, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.01.008

Li, S., & Lajoie, S. P. (2022). Cognitive engagement in self-regulated learning: An integrative model. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 37, 833–852.

Marchand, G., & Skinner, E. A. (2007). Motivational dynamics of children’s academic help-seeking and concealment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.65

McEown, K., & McEown, S. (2018). Individual, parental and teacher support factors of self-regulation in Japanese students. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2018.1468761

Mega, C., Ronconi, L., & Beni, R. D. (2014). What makes a good student? How emotions, self-regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033546

Mendoza, N. B., & Ronnel, B. K. (2022). The social contagion of work avoidance goals in school and its influence on student (dis)engagement. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 37, 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00521-1

Merett, F. N. M., Bzulneck, J. A., De-Oliveira, K. L., & Rufini, S. É. (2020). University students profiles of self-regulated learning and motivation. Educational Psychology, 37(e180126), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202037e180126

Miele, D. B., & Scholer, A. A. (2016). Self-regulation of motivation. In K. R. Wentzel & D. B. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 363–384). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Miele, D. B., & Scholer, A. A. (2018). The role of metamotivational monitoring in motivation regulation. Educational Psychologist, 53(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1371601

Monroy, J. A., Cheung, R. Y. M., & Cheung, C. S. (2019). Affective underpinnings of the association between autonomy support and self-regulated learning. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 65(4), 402–422. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.65.4.0402

Moreno, C., Ramos-Valverde, P., Rivera, F., García-Moya, I., Jiménez-Iglesias, A., Sánchez-Queija, I., Moreno-Maldonado, C., & Morgan, A. (2014). Cuestionario HBSC 2014—España. Ministerio de Sanidad. Retrieved Oct 2, 2023, from https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/entornosSaludables/escuela/estudioHBSC/cuestionarios.htm

Newman, R. S. (2000). Social Influences on the development of children’s adaptive help seeking: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Developmental Review, 20, 350–404. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1999.0502

OECD. (2018). The future of education and skills. OECD. Retrieved Oct 2, 2023, https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Perry, J. C., Fisher, A. L., Caemmerer, J. M., Keith, T. Z., & Poklar, A. E. (2018). The role of social support and coping skills in promoting self-regulated learning among urban youth. Youth & Society, 50(4), 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X15618313

Puustinen, M., & Puulkinen, L. (2001). Models of self-regulated learning: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 45(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830120074206

Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Jang, H. (2008). Understanding and promoting autonomous self-regulation: A self-determination theory perspective. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Rodríguez-Ayán, M. N. R., & Ruiz, M. A. (2008). Atenuación de la asimetría y de la curtosis de las puntuaciones observadas mediante transformaciones de variables: Incidencia sobre la estructura factorial. Psicológica, 29(2), 205–227.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2008). Gender differences in the relationship between perceived social support and student adjustment during early adolescence. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 496–514. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.496

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–34). University of Rochester Press.

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460–475. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1033

Schunk, D. H., & Greene, J. A. (2018). Historical, contemporary, and future perspectives on self-regulated learning performance. In D. H. Schunk & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2013). Self-regulation and learning. In W. M. Reynolds & G. E. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Educational psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 59–78). John Wiley & Sons.

Schwarzer, R., & Knoll, N. (2007). Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. International Journal of Psychology, 42(4), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701396641

Schweder, S. (2020). Mastery goals, positive emotions and learning behavior in self-directed vs. Teacher-directed learning. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00421-z

Schwinger, M., & Otterpohl, N. (2017). Which one works best? Considering the relative importance of motivational regulation strategies. Learning and Individual Differences, 53, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.12.003

Sideridis, G. D., & Kaplan, A. (2011). Achievement goals and persistence across tasks: The roles of failure and success. The Journal of Experimental Education, 79, 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2010.539634

Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840

Smit, K., Brabander, D., Cornelis, J., Boekaerts, M., & Martens, R. L. (2017). The self-regulation of motivation: Motivational strategies as mediator between motivational beliefs and engagement for learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 82, 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.01.006

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., Luyckx, K., & Goossens, L. (2007). Conceptualizing parental autonomy support: Adolescent perceptions of promotion of independence versus promotion of volitional functioning. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 633–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.633

Song, J., Bong, M., Lee, K., & Kim, S. (2015). Longitudinal investigation into the role of perceived social support in adolescents’ academic motivation and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 821–841. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000016

Stiller, J. D., & Ryan, R. M. (1992). Teachers, parents, and student motivation: The effects of involvement and autonomy support. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Retrieved Oct 2, 2023, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED348759

Stroet, K., Opdenakker, M. C., & Minnaert, A. (2013). Effects of need supportive teaching on early adolescents’ motivation and engagement: A review of the literature. Educational Research Review, 9, 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.11.003

Suárez-Riveiro, J. M., & Fernández-Suárez, A. P. (2011). Evaluación de las estrategias de autorregulación afectivo-motivacional de los estudiantes: Las EEMA-VS. Anales de Psicología, 27(2), 369–380.

Suárez-Riveiro, J. M., Fernández-Suárez, A. P., Rubio, V., & Zamora, Á. (2016). Incidencia de las estrategias motivacionales de valor sobre las estrategias cognitivas y metacognitivas en estudiantes de secundaria [Incidence of value motivational strategies on high school students’ cognitive and metacognitive strategies]. Revista Complutense de Educación, 27(2), 421–435. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_RCED.2016.v27.n2.46329

Suárez-Riveiro, J. M., Gonzalez-Cabanach, R., & Valle, A. (2001). Multiple-goal pursuit and its relation to cognitive, self-regulatory, and motivational strategies. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158677

Takashiro, N. (2016). What are the relationships between college students’ goal orientations and learning strategies? Psychological Thought, 9(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.5964/psyct.v9i2.169

Wang, C. (2013). Achievement goals, motivational self-regulation, and academic adjustment among elite Chinese high school students [Doctoral dissertation, Ball State University]. Ball State University. Retrieved Oct 2, 2023, http://cardinalscholar.bsu.edu/handle/20.500.14291/197414

Wang, C., Shim, S. S., & Wolters, C. A. (2017). Achievement goals, motivational self-talk, and academic engagement among Chinese students. Asia Pacific Education Review, 18, 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-017-9495-4

Wolters, C. A. (2003). Regulation of motivation: Evaluating an underemphasized aspect of self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(4), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3804_1

Wolters, C. A. (2011). Regulation of motivation: Contextual and social aspects. Teachers College Record, 113(2), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/01614681111130020

Won, S., & Yu, S. L. (2018). Relations of perceived parental autonomy support and control with adolescents’ academic time management and procrastination. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.12.001

Wood, R. E., Whelan, J., Sojo, V., & Wong, M. (2013). Goals, goal orientations, strategies, and performance. In E. A. Locke & G. P. Latham (Eds.), New developments in goal setting and task performance (pp. 90-114). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Worley, J. T., Meter, D. J., Ramirez Hall, A., Nishina, A., & Medina, M. A. (2023). Prospective associations between peer support, academic competence, and anxiety in college students. Social Psychology of Education, 26, 1017–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09781-3

Yeo, G., Loft, S., Xiao, T., & Kiewitz, C. (2009). Goal orientations and performance: Differential relationships across levels of analysis and as a function of task demands. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 710–726. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015044

Yildirim, S. (2012). Teacher support, motivation, learning strategy use, and achievement: A multilevel mediation model. The Journal of Experiential Education, 80(2), 150–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2011.596855

Zeidner, M., & Stoeger, H. (2019). Self-regulated learning (SRL): A guide for the perplexed. High Ability Studies, 30(1–2), 9–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2019.1589369

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2012). Motivation: An essential dimension of self-regulated learning. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 1–30). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Grant PID2021-126981OB-I0 funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe” and by Xunta de Galicia (ED431C 2022/17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZM-L: investigation, writing original draft preparation, data curation, visualization; VM: formal analysis, validation, data curation; EV: investigation, writing—review and editing; MªEM: investigation, resources, visualization; CT: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Compostela (registration USC-29/2020).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Z. Martínez-López. Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, C/Xosé María Suárez Núñez, s/n, Campus Vida, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain. Email: zeltia.martinez@usc.es

Current Themes of Research

Academic and psychosocial adjustment. Adolescence. Perceived social support. Self-regulated learning.

Relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education

Villar, E., Martínez-López, Z., Mayo, M. E., Braña, T., Rodríguez, M., & Tinajero, C. (2022). A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Relationship between Social Support and Binge Drinking among Adolescents and Emerging Adults. Youth, 2(4), 570-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040041

Martínez-López, Z., Villar, E., Castro, M., & Tinajero, C. (2021). Self-regulation of academic emotions: recent research and prospective view. Anales de Psicología, 37(3), 529- 540. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.415651

Mayo, M. E., Iglesias-Souto, P. M., Martínez-López, Z., & Taboada-Ares, E. M. (2021). Do medical students feel trained enough to communicate bad news? Educación Médica, 22(3), 135-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2020.07.007

Tinajero, C., Martínez-López, Z., Rodríguez, M.S., & Páramo, M.F. (2020). Perceived social support as a predictor of academic success in Spanish university students. Anales de Psicología. 36 (1), 134-142. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.344141

Pérez-Pereira, M., Martínez-López, Z., & Maneiro, L. (2020). Longitudinal relationships between reading abilities, phonological awareness, language abilities and executive functions: Comparison of low risk preterm and full-term children. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00468

Tinajero, C., Martínez-López, Z., Rodríguez, M.S., Guisande, M.A., & Páramo, M.F. (2015). Gender and socioeconomic status differences in university students' perception of social support. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30 (2), 227-244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-014-0234-5

V.E. Moran. Institute for Social, Territorial and Educational Research, National Council for Scientific and Technical Research-National University of Rio Cuarto, Rio Cuarto, Argentina. Email: moranvaleria@gmail.com

Current Themes of Research:

Adolescence. Adults. Educational measurement.

Relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Azpilicueta, A. E., Cupani, M., Ghío, F. B., Morán, V. E., Garrido, S. J., & Bruzzone, M. (2022). Career decision self-efficacy Item Bank: A Simulation study. Current Psychology, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03749-w

Garrido, S. J., Azpilicueta, A. E., Morán, V. E., & Cupani, M. (2022). Psychometric Properties of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T) in Argentinian Adolescents. Psychological Thought, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.37708/psyct.v15i2.725

Morán, V.E., Curi, M. V., Fabbro, N. & Alessandrini, L. (2022). Argentinean validation of the Social Connectedness Scale. Psychologica, 65, e065003. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8606_65_3

Cupani, M., Moran, V., Azpilicueta, A., Piccolo, N., & Artuso, F. (2019). Alternate Forms Public Domain RIASEC Markers for Interests and Self-Efficacy: Spanish version. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 17 (2), 359-382. http://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v17i48.2136.

Morán, V. E., Zalazar-Jaime, M. F., & Cupani, M. (2019). Adaptación argentina de dos medidas de Autoeficacia en el ámbito académico universitario. Contextos Educativos, (24), 197-211.

Azpilicueta, A. E., Cupani, M., Morán, V. E., & Garrido, S. (2019). Adaptación de tres medidas de variables involucradas en la elección de carrera: Indecisión de carrera, decisión de carrera y ansiedad decisional. Perspectivas en Psicología, 16(1), 26-37.

Morán, V. E., Cupani, M., Azpilicueta, A. E., Garrido, S. J., & Martinatto, C. A. (2019). Argentinean Validation of the Factorial Structure of the Learning Experiences Questionnaire (LEQ). Journal of Career Development, 0894845319828536. https://doi.org/10.1177/089484531982853

E. Villar. Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, C/Xosé María Suárez Núñez, s/n, Campus Vida, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain. Email: evavillar.garcia@usc.es

Current Themes of Research

Academic and psychosocial adjustment. Adolescence. Perceived social support. Self-regulated learning.

Relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education

Villar, E., Martínez-López, Z., Mayo, M. E., Braña, T., Rodríguez, M., & Tinajero, C. (2022). A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Relationship between Social Support and Binge Drinking among Adolescents and Emerging Adults. Youth, 2(4), 570-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040041

Martínez-López, Z., Villar, E., Castro, M., & Tinajero, C. (2021). Self-regulation of academic emotions: recent research and prospective view. Anales de Psicología, 37(3), 529- 540. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.415651

M.E. Mayo. Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, C/Xosé María Suárez Núñez, s/n, Campus Vida, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain. Email: emma.mayo@usc.es

Current Themes of Research

Psychosocial adjustment. Learning disabilities. Children, young adults and families.

Perceived social support.

Relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education

Villar, E., Martínez-López, Z., Mayo, M. E., Braña, T., Rodríguez, M., & Tinajero, C. (2022). A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Relationship between Social Support and Binge Drinking among Adolescents and Emerging Adults. Youth, 2(4), 570-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040041

Mayo, M. E., Iglesias-Souto, P. M., Martínez-López, Z., & Taboada-Ares, E. M. (2021). Do medical students feel trained enough to communicate bad news? Educación Médica, 22(3), 135-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2020.07.007

Mayo, M. E., Fernández de la Iglesia, J. D. C., & Roget, F. (2020). La atención a la diversidad en el aula: dificultades y necesidades del profesorado de educación secundaria y universidad. Contextos Educativos. Revista de Educación, 25, 257-274. https://doi.org/10.18172/con.3734

Mayo, M.E., Taboada-Ares, E.M., Iglesias-Souto, P.M., Real, J.E., & Dosil, A. (2018). Family Environment and Coping Strategies for Families Dealing with Children that are Blind or Visually Impaired. Current Perspectives in Depression and Anxiety. https://doi.org/10.29011/CPDA-101.100001

Mayo, E. M., González-Freire, B., & Trillo, V. M. (2015). Ansiedad ante los exámenes en la universidad: Estudio de caso único. Ansiedad y estrés, 21(1), 21-33.

C. Tinajero. Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, C/Xosé María Suárez Núñez, s/n, Campus Vida, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain. Email: carolina.tinajero@usc.es

Current Themes of Research

Academic and psychosocial adjustment. Adolescence. Perceived social support. Self-regulated learning.

Relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education

Villar, E., Martínez-López, Z., Mayo, M. E., Braña, T., Rodríguez, M., & Tinajero, C. (2022). A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Relationship between Social Support and Binge Drinking among Adolescents and Emerging Adults. Youth, 2(4), 570-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040041

Martínez-López, Z., Villar, E., Castro, M., & Tinajero, C. (2021). Self-regulation of academic emotions: recent research and prospective view. Anales de Psicología, 37(3), 529- 540. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.415651

Páramo, M.F., Cadaveira, F., Tinajero, C., & Rodríguez, M.S. (2020). Binge drinking, cannabis co-consumption and academic achievement in first year university students in Spain: Academic adjustment as a mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (542), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020542

Tinajero, C., Martínez-López, Z., Rodríguez, M.S., & Páramo, M.F. (2020). Perceived social support as a predictor of academic success in Spanish university students. Anales de Psicología. 36 (1), 134-142. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.344141

Tinajero, C., Cadaveira, F., Rodríguez, M.S., & Páramo, M.F. (2019). Perceived social support from significant others among binge drinking and polyconsuming Spanish university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16 (4506), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224506

Páramo, M.F., Araújo, A.M., Tinajero, C., Almeida, L.S., & Rodríguez, M.S. (2017). Predictors of students’ adjustment during transition to university in Spain. Psicothema, 29 (1), 67-72. 2017. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.40

Rodríguez, M.S., Tinajero, C., & Páramo, M.F. (2017). Pre-entry characteristics, perceived social support, adjustment and academic achievement in first-year Spanish university students: A path model. Journal of Psychology, 151(8), 722- 738. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1372351

Páramo, M.F., Araújo, A.M., Tinajero, C., Almeida, L.S., & Rodríguez, M.S. (2017). Predictors of students’ adjustment during transition to university in Spain. Psicothema, 29 (1), 67-72. 2017. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.40

Tinajero, C., Martínez-López, Z., Rodríguez, M.S., Guisande, M.A., & Páramo, M.F. (2015). Gender and socioeconomic status differences in university students' perception of social support. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30 (2), 227-244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-014-0234-5

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-López, Z., Moran, V.E., Mayo, M.E. et al. Perceived social support and its relationship with self-regulated learning, goal orientation self-management, and academic achievement. Eur J Psychol Educ 39, 813–835 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00752-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00752-y