Abstract

Since there has been no clear overview of educational practices that benefit high-ability students in mixed-ability classrooms in grades one to six, this review aims to provide insight into the effects of educational practices on the cognitive and affective-motivational learning outcomes of high-ability students. In order to identify these educational practices, we conducted a review of the existing literature, comprising a systematic search of the Education Resources Information Center and Web of Science databases for studies from the last 25 years. Only empirical studies that investigated the impact of interventions were included. Applying these criteria resulted in the inclusion of seventeen studies. Four different educational practices were shown to have a positive impact on cognitive learning outcomes: providing dynamic feedback, enhancing self-regulated learning, adjusting the curriculum and providing differentiated instruction. The impact of educational practices on affective-motivational learning outcomes was inconclusive. Based on this review, we conclude that teachers can help high-ability students in mixed-ability classrooms in grades one to six across various educational contexts using the educational practices reported in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since the 1980s, international research on high-ability (HA) students has increased (Kulik & Kulik, 1984). We define HA students as students who excel in the intellectual (or cognitive) domain (Gagné, 2004; Heller et al., 2000; Renzulli, 2005). In the USA, in particular, a significant knowledge base has been developed and various programmes for HA students have been implemented in the education system. As there is a trend in (mainstream) education towards improving and adapting the learning environment as much as possible to the individual needs of diverse learners, this topic of research is becoming increasingly important (Amor et al., 2019; Van Mieghem, et al., 2018). It is especially important in elementary education to meet the needs of HA students to prevent loss of motivation, as this can have a negative effect on their further school careers (Snyder & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2013; Vu et al., 2021). First- to sixth-grade classrooms are typically more heterogeneous in terms of cognitive ability than classes of older students. Most existing studies recommend part- or full-time separation, such as pull-out or accelerated programmes, in which HA or gifted students are instructed in a setting outside the classroom (Bailey et al., 2012; García-Martínez et al., 2021; Jen, 2017; Kim, 2016; Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2016). Although cognitive learning outcomes are often the main focus, many of the existing review studies report one or more positive effects on the social and emotional development of HA students. Research has continued to suggest that the affective and motivational aspects of learning can be beneficial for HA students’ cognitive development (Gagné, 2004; Siegle & McCoach, 2005), emphasising the importance of gaining insight into both the cognitive and the affective and motivational learning outcomes. Compared to these specific programmes, less is known about the effectiveness of educational practices implemented in regular mixed-ability classrooms for cognitively gifted and HA students. Thus, it remains unclear which educational practices can challenge and stimulate HA students in mixed-ability classrooms. This review aims to fill the gap in the literature by systematically exploring the effects of educational practices implemented in mixed-ability first- to sixth-grade classrooms on the cognitive and affective-motivational learning outcomes of HA students.

Theoretical framework

High-ability students

Assumptions about and the criteria for ‘giftedness’ differ according to the theoretical model employed (Gagné, 1985, 2004; Heller et al., 2000; Renzulli, 1999; Siegle & McCoach, 2005; Subotnik et al., 2011). Across all models, HA students are those who excel in a certain domain. Since the intellectual (or cognitive) domain is considered important in education, in this review, we focus on giftedness in the cognitive domain (Gagné, 2004; Heller et al., 2000; Renzulli, 2005). Theoretical and empirical studies consider different non-cognitive personal and environmental factors to be important for developing high ability into outstanding mastery. For example, students with high self-regulation skills and high levels of autonomous motivation tend to show higher achievement (Reis & McCoach, 2000; Snyder & Wormington, 2020). Although different terms are in use (Dai & Chen, 2013), recent research often uses the term ‘high-ability students’ (Barbier, et al., 2022; Miller & Neumeister, 2017) to refer to students who have the cognitive ability to reach the highest levels of academic success (Dare et al., 2019). There is no clear cut-off in terms of scores on measurements of cognitive ability; they range from the top 20% to the top 1% (Gagné, 2004; Renzulli, 2005; Terman, 1925). From here on, we will use the term ‘HA students’.

HA students significantly differ from their non-HA peers on certain cognitive aspects. First, HA students tend to have an excellent memory and can recall knowledge more efficiently than their typical peers (Aubry et al., 2021; Giofrè et al., 2013; Rodríguez-Naveiras et al., 2019). Also, they can process information faster (Paz-Baruch et al., 2014; Spiegel & Bryant, 1978). Additionally, research points out that HA students are better at solving problems than their peers and can use various strategies to do so (Abdulla Alabbasi et al., 2021). Furthermore, they generally demonstrate better higher-order thinking skills, including critical thinking (Kettler, 2014). In addition to these shared (meta)cognitive characteristics, HA students show differences in motivation, interests, personality, and other non-cognitive characteristics that impact the development of outstanding ability into performance at school (Gagné, 2004).

Since HA students differ from average students, it is important to consider their advanced cognitive skills and related needs. To develop their abilities and skills, HA students need a stimulating, motivating and challenging learning environment that takes into account the variety of their needs. Teachers play an important role in creating such an environment. Because student performance is the result of the interaction between individuals and their environment (Gietz, 2011; Lewin, 1963), a lack of fit can lead to motivational problems and underperformance (Barbier, et al., 2022; Snyder & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2013). Teachers thus have a responsibility to create an appropriate learning environment, also for HA students. Therefore, it is relevant to look into evidence-based educational practices that benefit HA students.

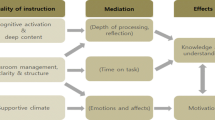

Effective educational practices

Numerous theoretical and instructional models in the domain of learning and instruction elaborate on educational practices that are effective in enhancing student motivation and achievement (De Corte, 2013; Deci & Ryan, 2002; Pintrich, 2003; Tomlinson et al., 2003). Some models are broad and applicable to all students; for example, all students need to feel in control of their own behaviour (Deci & Ryan, 2002). Others take into account students’ different needs; for example, instruction should always ‘be in advance’ of a student’s current level of mastery (Tomlinson et al., 2003) or focus on creating empowering learning environments; for example, self-regulation can help HA students become competent (De Corte, 2013; Pintrich, 2003).

Based on previous studies on educating HA students, we have some understanding of effective educational practices. A meta-analysis by Kim (2016) showed the positive effects of summer and after-school enrichment programmes on the academic achievement and socio-emotional development of gifted students. A great deal of research has also explored the effect of grouping students (e.g. in homogeneous groups outside the regular mixed-ability classroom or cross-year groups) and found that it results in positive learning outcomes for HA students (Kulik & Kulik, 1992; Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2016). In the research on gifted students and gifted pedagogy, there are many recommendations for such classes (VanTassel-Baska, 2008). In terms of accelerating the curriculum, research has demonstrated the positive effects of allowing students to skip a course or grade (Kulik & Kulik, 1984; Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2016). Little et al. (2007) identified five principles for educating gifted and talented students based on theoretical and scientific research: daily challenge, the opportunity to work on personal talents, accelerating the subject matter, an adapted curriculum and the possibility of social interaction with talented peers. A review conducted by Rogers (2007) formulated similar ‘lessons learned’ for educating gifted students. However, there was no clear quality check of the empirical studies included. A recent review study by García-Martínez et al. (2021) on educational interventions with HA students included a range of effective interventions, most of which took place outside the mixed-ability classroom (e.g. acceleration or pull-out enrichment programmes).

The current study

Keeping in mind that previous studies provide little insight into educational practices for HA students in regular mixed-ability elementary classrooms, this review aims to contribute to the field. By focusing on intervention studies, we aim to identify ‘what works’ for HA students in mixed-ability classrooms in grades one to six.

The research questions are as follows.

-

1.

Which educational practices for HA students have been examined in mixed-ability first- to sixth-grade classrooms?

-

2.

What are the effects of these educational practices on cognitive learning outcomes?

-

3.

What are the effects of these educational practices on affective-motivational learning outcomes?

We use ‘student learning outcomes’ as an umbrella term to refer to many different aspects of learning, such as cognitive, metacognitive and affective-motivational learning outcomes. Cognitive outcomes are defined as the development or acquisition of cognitive competencies in one or more academic fields (Gagné, 2004). Metacognitive outcomes include the development of views and beliefs about learning, the formulation of learning objectives and the attempt to monitor, regulate and control cognition, motivation and behaviour (Pintrich, 2000; Vermunt, 1996). Affective-motivational outcomes include aspects such as motivating, judging or evaluating oneself and experiencing emotions (Vermunt & Donche, 2017; Vermunt, 1996). These affective-motivational outcomes are important catalysts for the developmental processes of HA students (Gagné, 2004).

Methodology

Search

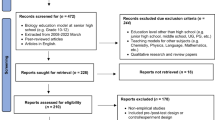

In the first phase, the search was restricted to peer-reviewed articles in academic journals to ensure a minimum standard of quality. We systematically entered search terms into two databases: the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and Web of Science (WoS), which includes the Social Sciences Citation Index, the Science Citation Index Expanded and the Arts & Humanities Citation Index. In addition to search terms concerning the research population (‘high-ability’, ‘gifted’, ‘high-achieving’), search terms relevant to educational practices were added (‘instruction’, ‘intervention’, ‘differentiation’, ‘teaching strategy’). Second, we included terms related to (meta-)cognitive learning outcomes (‘achievement’, ‘learning’) and affective-motivational learning outcomes (‘motivation’, ‘engagement’, ‘well-being’). Combining the different search terms using Boolean terms (e.g. ‘high-ability OR gifted OR high-achieving) AND instruction AND achievement’) resulted in twenty search queries.

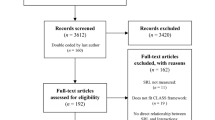

Selection

To ensure the reproducibility and transparency of the review process, the selection procedure will be described in accordance with the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009) (Addendum 1). The year of publication was limited to the last twenty-five years (1996–2021). This was imposed to ensure that the research was not too far removed from current classroom contexts. The search yielded 3563 empirical articles. After removing duplicates, 1754 articles remained. In the second phase, we reduced and refined this set of articles by reading their titles and abstracts. Three researchers each screened a different set of articles based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1). To ensure the trustworthiness and the validity of the screening, several meetings were organised to address all questions that emerged during coding. When an article did not meet one or more of the criteria, it was excluded (see Table 1). This selection procedure yielded 129 articles. In the third phase, two researchers read the full articles, critically assessing their relevance and methodology. In doing so, we considered the main criteria developed by Aveyard (2014) and that of the CASP-tool (CASP, 2018). Thus, each study had to have (1) a well-specified research question, aim or hypothesis; (2) a well-described subject sample; (3) a well-described procedure for collecting data, with a clear focus on cognitive and/or affective-motivational learning outcomes; (4) a clear description of the intervention in the classroom (studies could have a control [no intervention] group and a follow-up measurement, but these were not required) and (5) a clear description of the findings. A more specific description of these criteria is given in Addendum 2. We did not include any review studies that reported on findings from a secondary source. There were minimal disagreements between the researchers in this phase. The small disagreements concerned the results of the studies (e.g. if the effect on HA students compared to other students was sufficiently clear). The first author made the final selection, with the agreement of the co-authors. Upon completion of this phase, 17 articles remained, each reporting on a different study.

Analysis of the literature

First, the general characteristics of the studies were identified (see Addendum 3). This analysis indicated various similarities and differences and offered possibilities for clustering the studies based on different perspectives: context (country and classroom), age, sample, definition of HA students and identification of the research participants. The ages of the participants ranged from six to thirteen. HA students were defined and identified differently in each study. Terms used included ‘HA students’, ‘high-achievers’, ‘advanced readers’, ‘potential gifted’, ‘gifted students’ and ‘highly-intelligent students’. In most of the studies, a cognitive ability test or a standardised math test was used to identify these students. In some studies, the nomination of HA students by teachers or parents was taken into account. Most of the studies were conducted in the USA or Europe and focused on a specific course such as mathematics or language. Second, we looked into the different educational practices (see Table 2). Thematic analysis was used to interpret the data. Next, inductive coding was applied to provide an overview of the educational practices used in the different studies. Cognitive and/or affective-motivational learning outcomes were taken into account in the analysis. Although qualitative research was not excluded beforehand, only three studies opted for mixed-methods research; all the others were quantitative. All studies applied a pre- and post-test design; twelve included a control group (who did not receive the intervention), which indicates that they were high-quality intervention studies. In order to interpret the results, Cohen’s (1988) rule of thumb was followed: Effects were identified as small, medium or large. The number of participants ranged from 20 to 3514 students (not all were HA students), and interventions lasted between 90 min and 5 years. In sixteen studies, teachers received training so that they became experts in the intervention; this enhanced the implementation fidelity.

Results

Educational practices

Table 2 presents an overview of the different educational practices implemented for HA students in mixed-ability first- through sixth-grade classrooms and their effect on cognitive and/or affective-motivational learning outcomes. We distinguish five different ways educational practices were applied to foster positive learning outcomes for HA students.

First, three studies (Popa & Pauc, 2015; van Dijk et al., 2016; Vogelaar et al., 2019) focused on the use of ‘dynamic feedback’ or ‘dynamic assessment’. These interventions consisted of prompting students during class by giving them hints or feedback. The goal was for students to become more competent in autonomously analysing their learning processes and errors.

Second, three studies (Obergriesser & Stoeger, 2015; Sontag & Stoeger, 2015; Stoeger & Ziegler, 2005) focused on self-regulated learning. The teachers reflected on various topics with their students, such as time management, how they studied at home and how to set goals. They gave tips and exercises related to cognitive and metacognitive strategies. The goal of this study was to enhance students’ competence in self-regulated learning.

Third, four studies (McCoach et al., 2014; Reis et al., 1998; Robinson et al., 2014; VanTassel-Baska et al., 2002) explored the impact of adjusting the curriculum. They either focused solely on enrichment (e.g. providing more challenging tasks; stimulating higher-order thinking skills) or combined it with compacting (e.g. skipping unnecessary or repetitive and exercise material) and/or problem-based inquiry. The interventions were designed for the whole class and thus included HA students in the treatment group. The degree of compacting varied according to the students’ ability level. The goal of these interventions was to enhance the learning and achievement of (HA) students.

Fourth, two studies (Lee et al., 2019; Saleh et al., 2005) examined the impact of homogenous and heterogeneous grouping on the learning of HA students. Saleh et al. (2005) focused on within-class grouping, both homogeneous and heterogeneous. Lee et al. (2019) designed an online collaboration, creating heterogeneous pairs of students from different schools.

Finally, five studies used differentiated instruction, involving a combination of educational practices (Faber et al., 2018; Guthrie et al., 2009; Hunsaker et al., 2010; Maker et al., 1996; Prast et al., 2018). Each study used a specific instructional strategy or programme, respectively labelled ‘DBDM’ (Data-Based Decision Making), ‘CORI-reading strategies’ (Concept Orientated Reading Instruction), ‘Project ARAR’ (Advanced Readers At Risk), the DISCOVER project and the ‘cycle of differentiation’. As shown in Table 2, the studies used varying forms of differentiated instruction. Faber et al. (2018) used within-class ability grouping and differentiated instruction. Guthrie et al. (2009) implemented motivational practices along with Concept Oriented Reading Instruction. This included giving HA students choices, making the content relevant to students, providing texts in the zone of proximal development and teaching students how to monitor their own comprehension of a text. Hunsaker et al. (2010) focused on differentiation by carefully identifying students, preparing adapted instruction in terms of content, designing instructional activities for HA students and conducting ongoing evaluations. Maker et al. (1996) implemented different classroom teaching strategies and a curriculum based on the theory of multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1983), the principles of differentiation and the integration of culturally relevant content. Finally, Prast et al. (2018) used a ‘cycle of differentiation’: Teachers identified students’ current skills and divided them accordingly into homogeneous ability groups. Afterwards, teachers set different goals and used different practices and forms of instruction to meet the needs of each group. The goal of these studies was to enhance the learning, achievement and/or motivation of the students.

Effects on cognitive learning outcomes

The majority of studies (eleven out of fifteen) found significant positive effects on the cognitive learning outcomes of HA students. The effect sizes varied from small to large (see Table 2).

First, providing dynamic feedback in the classroom had positive effects on cognitive learning processes and/or outcomes (Popa & Pauc, 2015; van Dijk et al., 2016; Vogelaar et al., 2019). Two studies (Popa & Pauc, 2015; Vogelaar et al., 2019) found that dynamic assessment enhanced cognitive learning outcomes for all students, including HA students. Although van Dijk et al. (2016) did not find a significant effect on HA students’ learning outcomes, they did find a positive effect on the learning process.

Second, two of the three studies focusing on improving self-regulated learning reported positive outcomes regarding the cognitive performance of HA students (Obergriesser & Stoeger, 2015; Sontag & Stoeger, 2015). One self-regulation programme (Stoeger & Ziegler, 2005) found no significant effect on the cognitive learning outcomes of HA students.

Third, mainly positive outcomes were found for approaches that adapted the curriculum. In the study by McCoach et al. (2014), enriching the curriculum for HA students had a small positive effect, especially in disadvantaged schools. In the study by Reis et al. (1998), the results indicated that the achievement tests scores of HA students whose curriculum was compacted (40–50%) did not differ significantly from those whose curriculum was not compacted. Curriculum compacting and enrichment thus did not harm HA students and was recommended to prevent boredom. In the study by VanTassel-Baska et al. (2002), the implementation of an advanced curriculum that stimulated higher-order thinking and concept development resulted in greater gains with regard to literary analysis, interpretation and writing in the intervention group than in the control group. The study including a curriculum centred on problem-based inquiry (Robinson et al., 2014) yielded positive findings, as HA students who followed this curriculum performed better on the post-test than the control group.

Fourth, the research on grouping by Saleh et al. (2005) found no differences between homogenous and heterogeneous within-class grouping for HA students. In the research by Lee et al. (2019) on heterogeneous pairing, HA students in the intervention group performed better than those in the control group who worked individually.

Finally, there were mixed but mostly positive outcomes in the four studies that focused on multiple educational practices. Faber et al. (2018) found no significant effects of the DBDM intervention, while Guthrie et al. (2009) found positive effects on some cognitive learning outcomes, but not on all measures (e.g. reading fluency). Regarding the ARAR approach (Hunsaker et al., 2010), this approach was positively correlated with improved literary analysis skills. The DISCOVER project mainly improved HA students’ problem-solving skills when their teacher implemented the curriculum and the different instructional strategies correctly (‘high implementer’). Moreover, the cycle of differentiation employed by Prast et al. (2018) yielded a positive effect on students’ learning outcomes in the first year of implementation but had no effect in the second year.

Effects on affective-motivational learning outcomes

Six studies included affective-motivational outcome variables such as motivation, self-efficacy and enjoyment. When considering the different categories (using dynamic feedback, enhancing self-regulated learning, adjusting the curriculum, grouping and differentiated instruction), at least one study per category included an affective-motivational outcome measure except for using an adapted curriculum, for which only cognitive learning outcomes were reported.

First, providing dynamic feedback by prompting and giving hints had no significant effect on the motivation of HA students. Second, the studies that tried to enhance self-regulated learning included various affective-motivational measures (e.g. self-efficacy) and reported different effects. For instance, Obergriesser and Stoeger (2015) found no effect on the anxiety of HA students and only found an improvement in the self-efficacy of HA underachievers. Stoeger and Ziegler (2005) considered gifted underachievers and reported a significant effect on self-efficacy. The results suggest that, when considering the affective-motivational outcome of self-efficacy, improving self-regulated learning is mainly effective for underachieving HA students. Stoeger and Ziegler (2005) also found a positive impact on reducing helplessness and no effect on ‘persistence when faced with challenging objectives’. Furthermore, regarding homogeneous or heterogeneous within-class grouping, no impact was found on motivation (Saleh et al., 2005). Finally, only one study that used multiple educational practices included measurements of affective-motivational learning outcomes, namely enjoyment (Hunsaker et al., 2010). In this study, small positive effects of using differentiated instruction on affective-motivational learning outcomes were found.

Conclusion and discussion

Compared to part- or full-time separation programmes for HA students, such as enrichment programmes (García-Martínez et al., 2021; Kim, 2016; Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2016), we know little about the effectiveness of educational practices implemented in mixed-ability classrooms for these students. To identify the impact of educational practices in first- to sixth-grade classrooms on the cognitive and/or affective-motivational learning outcomes of HA students, we conducted a systematic review of empirical studies investigating the impact of interventions.

First, we identified five within-class educational practices for HA students that have been studied in the past 25 years: using dynamic feedback, enhancing self-regulated learning, adjusting the curriculum, within-class grouping and providing differentiated instruction. These practices respond to the cognitive and non-cognitive characteristics and needs of HA students mentioned in the theoretical framework. For example, giving dynamic feedback ensures that HA students have opportunities to improve their inquiry skills (Abdulla Alabbasi et al., 2021). Furthermore, by compacting and enriching the curriculum and/or differentiating their instruction, teachers provide HA students with the chance to learn at a faster pace and develop higher-order thinking skills (Steiner & Carr, 2003). Also, enhancing self-regulation skills such as self-assessment, goal setting and strategic planning contributes to converting these students’ cognitive ability into strong performance (Reis & McCoach, 2000). Moreover, in accordance with previous studies, grouping HA students together and providing them with more challenging work than their peers is a well-known effective educational practice (Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2016).

Second, regarding the effects of these educational practices on cognitive learning outcomes, many of them had positive effects, with effect sizes ranging from small to large. Positive effects were reported from providing dynamic feedback, enhancing self-regulated learning, adjusting the curriculum and using differentiated instruction. However, some studies showed no effect. Furthermore, effects also varied depending on the outcome measure and subgroup. We can state that adjusting the curriculum, providing dynamic feedback and enhancing self-regulated learning are most likely to be effective, given that the majority of studies, including those with large sample sizes, reported medium-to-large effect sizes. Adjusting the curriculum, in particular, was found to be effective in multiple large-scale studies. However, the use of differentiated instruction is supported by less empirical evidence since the study with the largest sample found that it had no effect and several studies did not report the effect size of their positive results.

Third, looking at the impact of the five identified educational practices on affective-motivational learning outcomes, the results were not straightforward. These practices either had no effect or varied effects, with mostly small effect sizes. A possible explanation is that affective-motivational effects only applied to certain subgroups in the measured samples. Enhancing self-regulated learning, for example, had a positive effect on self-efficacy and the reduction of helplessness, but only for underachieving HA students (Obergriesser & Stoeger, 2015; Stoeger & Ziegler, 2005). Besides these two studies, no other study included underachieving HA students (Reis & McCoach, 2000) as a subsample for separate analysis. As we know from the previous literature, underachievement is linked to various motivational problems (Snyder & Wormington, 2020; White et al., 2018). This review thus points out the relevance of including HA underachievers as a separate sample when studying the effect of educational practices in mixed-ability classrooms. A recent meta-analysis by Steenbergen-Hu et al. (2020) provides insight into the effectiveness of interventions specifically aimed at reducing underachievement among gifted students. We recommend further research on why some interventions work and the conditions under which they work.

It is important to interpret these findings with caution. For example, the homogeneous grouping has been shown to be effective for the cognitive learning outcomes of HA students in many studies (Kulik & Kulik, 1992; Rogers, 1993). Saleh et al. (2005), however, did not find that within-class grouping had a significant effect. In this study, both homogeneous and heterogeneous groupings were applied, but the authors did not make an explicit statement about curricular adjustments such as enrichment, compacting or acceleration. It is therefore unclear whether the insignificant effect was a consequence of grouping or how it was implemented. As Kulik and Kulik (1992) concluded, when grouping goes hand in hand with enrichment and acceleration, it has the greatest effect on student learning.

Furthermore, it is striking that fewer than half of the studies considered affective-motivational learning outcomes. Moreover, the studies that did include these outcomes identified a limited number of affective-motivational components (e.g. enjoyment). It would be valuable to consider other learning outcomes as well, such as goal valuation and behavioural, cognitive and emotional engagement. The framework adopted by Siegle and McCoach (2005) could inspire other researchers to examine affective-motivational learning outcomes more robustly.

There are some limitations to this research that need to be addressed. First, because few studies met the inclusion criteria, there was little similarity in the contexts and interventions of the various studies. Furthermore, the identification of HA or gifted students was different in every study. These differences in conceptualisation, along with the diversity of classroom contexts, did not allow us to conduct a quantitative meta-analysis. It is also important to recognise the impact of the educational contexts in which the studies were undertaken. For example, adjusting the curriculum was only studied in the USA, which has a different school system and pedagogy than countries in Europe. Therefore, it remains an important question whether the effectiveness demonstrated in these contexts will hold true in other educational contexts and cultures. Also, it is important to acknowledge that, due to the specific focus of this review, other interesting studies on educating HA students did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g. interventions outside the mixed-ability classroom or studies with no clear reporting on the learning outcomes of HA students; Callahan et al., 2014; Gavin et al., 2013). Moreover, possible publication bias needs to be taken into account, as this literature search was limited to the databases ERIC and WOS. However, including unpublished or non-peer-reviewed studies also has disadvantages with regard to quality control.

In this review, there was a wide variety of intervention-type research designs, with numbers of participants ranging from 36 to 2290 (not all HA) and interventions lasting from 90 min to 3 years. To extend the generalisability of the educational practices found to be effective in this review, it would be useful to replicate these studies. Another interesting avenue for future research would be to focus on the duration required for educational practices to be effective for HA students. Future research could, for instance, monitor the learning progress of a large group of HA students and test the impact of educational practices adopted by their teachers. In addition, the results that emerged from this set of studies were mostly quantitative. We, therefore, argue for empirical qualitative research to investigate in greater depth how effective educational practices are experienced by HA students in their specific context in mixed-ability classrooms. In terms of practice, it is important to keep in mind that the effective educational practices we highlighted were based on studies conducted in specific educational contexts in different countries. We recommend that practitioners always start with the needs of a given group of students, class or school. It is also important to check whether the educational practice(s) match(es) the prior knowledge, skills and attitudes required. Therefore, we recommend that teachers explore whether (and why) these educational practices work in their classroom or school context. One way to do this is by conducting practical research with their colleagues – for example, via the method of Lesson Study (Dudley, 2019; Vermunt et al., 2019).

Based on this review, we conclude that for grades one to six across different educational contexts, teachers can support HA students in heterogeneous classrooms through the educational practices reported in this study: using dynamic feedback, enhancing self-regulated learning, adjusting the curriculum and providing differentiated instruction. This is an important finding for both in-service teachers and teachers-in-training. Teachers should be prepared for the diversity of students they will encounter in the classroom and understand possible ways to support HA students through evidence-based educational practices. Although some of the reported practices are clearly specific to educating HA students (e.g. compacting and enriching the curriculum), others are fairly common strategies in the literature on effective teaching (e.g. self-regulated learning; De Corte et al., 2004; Tomlinson, 2017). It is therefore important to keep in mind that at least some of the educational practices discussed in this review can be useful for all students.

Data availability

All articles included in the review are published in academic journals.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

*References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the analysis.

Abdulla Alabbasi, A. M., Hafsyan, A. S. M., Runco, M. A., & AlSaleh, A. (2021). Problem finding, divergent thinking, and evaluative thinking among gifted and nongifted students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 44, 01623532211044539. https://doi.org/10.1177/01623532211044539

Amor, A. M., Hagiwara, M., Shogren, K. A., Thompson, J. R., Verdugo, M. Á., Burke, K. M., & Aguayo, V. (2019). International perspectives and trends in research on inclusive education: A systematic review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(12), 1277–1295. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1445304

Aubry, A., Gonthier, C., & Béatrice, B. (2021). Explaining the high working memory capacity of gifted children: Contributions of processing skills and executive control. Acta Psychologica, 218, 103358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103358

Aveyard, H. (2014). Doing a literature review in health and social care a practical guide (3rd ed.). Open University Press.

Barbier, K., Donche, V., & Verschueren, K. (2019). Academic (under)achievement of intellectually gifted students in the transition between primary and secondary education: An individual learner perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(2533). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02533

Barbier, K., Struyf, E., & Donche, V. (2022). Teachers' beliefs about and educational practices with high-ability students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103566

Bailey, R., Pearce, G., Smith, C., Sutherland, M., Stack, N., Winstanley, C., & Dickenson, M. (2012). Improving the educational achievement of gifted and talented students: A systematic review [Review]. Talent Development and Excellence, 4(1), 33–48. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84865637434&partnerID=40&md5=d5b7869d21006d16b5b485e61435b937.

Callahan, C., Moon, T., Oh, S., Azano, A., & Hailey, E. (2014). What works in gifted education. American Educational Research Journal, 52, 137–167. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214549448

CASP. (2018). Critical appraisal skills programme: Systematic review checklist. casp-uk.net

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Academic Press.

Dai, D. Y., & Chen, F. (2013). Three paradigms of gifted education: In search of conceptual clarity in research and practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57(3), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986213490020

Dare, L., Nowicki, E. A., & Smith, S. (2019). On deciding to accelerate: High-ability students identify key considerations. Gifted Child Quarterly, 63(3), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986219828073

De Corte, E. (2013). Giftedness considered from the perspective of research on learning and instruction. High Ability Studies, 24(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2013.780967

De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., & Masui, C. (2004). The CLIA-model: A framework for designing powerful learning environments for thinking and problem solving. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 19(4), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03173216

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. University of Rochester Press.

Dudley, P. (2019). Lesson Study: A handbook. Cambridge University.

*Faber, J. M., Glas, C. A. W., & Visscher, A. J. (2018). Differentiated instruction in a data-based decision-making context. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(1), 43-63.https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1366342

Gagné, F. (1985). Giftedness and talent: Reexamining a reexamination of the definitions. Gifted Child Quarterly, 29(3), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698628502900302

Gagné, F. (2004). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813042000314682

García-Martínez, I., Cáceres, R., Rosa, A., & P. León, S. (2021). Analysing educational interventions with gifted students. Systematic Review. Children, 8, 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8050365

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Gavin, M., Casa, T., Firmender, J., & Carroll, S. (2013). The impact of advanced geometry and measurement curriculum units on the mathematics achievement of first-grade students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986213479564

Gietz, C. (2011). Relations between student perceptions of their school environment and academic achievement. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 29, 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573514540415

Giofrè, D., Mammarella, I. C., & Cornoldi, C. (2013). The structure of working memory and how it relates to intelligence in children. Intelligence, 41(5), 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.06.006

*Guthrie, J. T., McRae, A., Coddington, C. S., Klauda, S. L., Wigfield, A., & Barbosa, P. (2009). Impacts of comprehensive reading instruction on diverse outcomes of low- and high-achieving readers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(3), 195-214.https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219408331039

Heller, K. A., Mönks, F. J., Subotnik, R., & Sternberg, R. (2000). International handbook of giftedness and talent. Elsevier.

*Hunsaker, S. L., Nielsen, A., & Bartlett, B. (2010). Correlates of teacher practices influencing student outcomes in reading instruction for advanced readers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 54(4), 273-282.https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986210374506

Jen, E. (2017). Affective interventions for high-ability students from 1984–2015: A review of published studies. Journal of Advanced Academics, 28(3), 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X17715305

Kettler, T. (2014). Critical thinking skills among elementary school students: Comparing identified gifted and general education student performance. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(2), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986214522508

Kim, M. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of enrichment programs on gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986216630607

Kulik, J. A., & Kulik, C.-L. (1984). Effects of accelerated instruction on students. Review of Educational Research, 54(3), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170454

Kulik, J. A., & Kulik, C.-L. (1992). Meta-analytic findings on grouping programs. Gifted Child Quarterly, 36(2), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698629203600204

*Lee, S. H., Bernstein, M., & Georgieva, Z. (2019). Online collaborative writing revision intervention outcomes for struggling and skilled writers: An initial finding. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 63(4), 297-307

Lewin, K. (1963). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. Tavistock.

Little, C. A., Feng, A. X. M., VanTassel-Baska, J., Rogers, K. B., & Avery, L. D. (2007). A study of curriculum effectiveness in social studies. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(3), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986207302722

*Maker, C. J., Rogers, J. A., Nielson, A. B., & Bauerle, P. R. (1996). Multiple intelligences, problem solving, and diversity in the general classroom. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 19(4), 437-460.https://doi.org/10.1177/016235329601900404

*McCoach, D. B., Gubbins, E. J., Foreman, J., Rubenstein, L. D., & Rambo-Hernandez, K. E. (2014). Evaluating the efficacy of using predifferentiated and enriched mathematics curricula for grade 3 students: A multisite cluster-randomized trial. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(4), 272-286.https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986214547631

Miller, A. L., & Neumeister, K. L. S. (2017). The influence of personality, parenting styles, and perfectionism on performance goal orientation in high ability students. Journal of Advanced Academics, 28(4), 313–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202x17730567

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Group TP. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(6), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

*Obergriesser, S., & Stoeger, H. (2015). The role of emotions, motivation, and learning behavior in underachievement and results of an intervention. High Ability Studies, 26(1), 167-190.https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2015.1043003

Paz-Baruch, N., Leikin, M., Aharon-Peretz, J., & Leikin, R. (2014). Speed of information processing in generally gifted and excelling-in-mathematics adolescents. High Ability Studies, 25(2), 143–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2014.971102

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation (pp. 451–502). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50043-3

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 667–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.667

*Popa, N. L., & Pauc, R. L. (2015). Dynamic assessment, potential giftedness and mathematics achievement in elementary school. Acta Didactica Napocensia, 8(2), 23–32. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1073270

*Prast, E. J., Van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Kroesbergen, E. H., & Van Luit, J. E. H. (2018). Differentiated instruction in primary mathematics: Effects of teacher professional development on student achievement. Learning and Instruction, 54, 22-34.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.01.009

Reis, S. M., & McCoach, D. B. (2000). The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly, 44(3), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620004400302

*Reis, S. M., Westberg, K. L., Kulikowich, J. M., & Purcell, J. H. (1998). Curriculum compacting and achievement test scores: What does the research say? Gifted Child Quarterly, 42(2), 123-129.https://doi.org/10.1177/001698629804200206

Renzulli, J. S. (1999). What is this thing called giftedness, and how do we develop it? A twenty-five year perspective. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 23(1), 3–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235329902300102

Renzulli, J. S. (2005). The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental model for creative productivity. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of Giftedness (pp. 246–279). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511610455.015

*Robinson, A., Dailey, D., Hughes, G., & Cotabish, A. (2014). The effects of a science-focused STEM intervention on gifted elementary students' science knowledge and skills. Journal of Advanced Academics, 25(3), 189–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X14533799

Rodríguez-Naveiras, E., Verche, E., Hernández-Lastiri, P., Montero, R., & Borges, A. (2019). Differences in working memory between gifted or talented students and community samples: A meta-analysis. Psicothema, 31(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2019.18

Rogers, K. B. (1993). Grouping the gifted and talented: Questions and answers. Roeper Review, 16(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783199309553526

Rogers, K. B. (2007). Lessons learned about educating the gifted and talented: A synthesis of the research on educational practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986207306324

*Saleh, M., Lazonder, A. W., & De Jong, T. (2005). Effects of within-class ability grouping on social interaction, achievement, and motivation. Instructional Science, 33(2), 105-119.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-004-6405-z

Siegle, D., & McCoach, D. B. (2005). Motivating gifted students. Prufrock Press.

Snyder, K., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2013). A developmental, person-centered approach to exploring multiple motivational pathways in gifted underachievement. Educational Psychologist, 48(4), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.835597

Snyder, K., & Wormington, S. (2020). Gifted underachievement and achievement motivation: The promise of breaking silos. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986220909179

*Sontag, C., & Stoeger, H. (2015). Can highly intelligent and high-achieving students benefit from training in self-regulated learning in a regular classroom context. Learning and Individual Differences, 41, 43-53.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.008

Spiegel, M. R., & Bryant, N. D. (1978). Is speed of processing information related to intelligence and achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(6), 904–910. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.70.6.904

Steenbergen-Hu, S., Makel, M. C., & Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (2016). What one hundred years of research says about the effects of ability grouping and acceleration on K-12 students’ academic achievement: Findings of two second-order meta-analyses. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 849–899. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316675417

Steenbergen-Hu, S., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Calvert, E. (2020). The effectiveness of current interventions to reverse the underachievement of gifted students: Findings of a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 132–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986220908601

Steiner, H., & Carr, M. (2003). Cognitive development in gifted children: Toward a more precise understanding of emerging differences in intelligence. Educational Psychology Review, 15, 215–246. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024636317011

*Stoeger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2005). Evaluation of an elementary classroom self-regulated learning program for gifted mathematics underachievers. International Education Journal, 6(2), 261–271. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ854979

Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(1), 3–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100611418056

Terman, L. M. (1925). Mental and physical traits of a thousand gifted children (Vol. 1). Stanford University Press.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). How to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms. ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., ..., & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest, and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: A review of literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2–3), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320302700203

*van Dijk, A. M., Eysink, T. H. S., & de Jong, T. (2016). Ability-related differences in performance of an inquiry task: The added value of prompts. Learning and Individual Differences, 47, 145-155.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.01.008

VanTassel-Baska, J. (2008). Curriculum development for gifted learners in science at the primary level. Revista Espanola De Pedagogia, 66(240), 283–295. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23766140.

*VanTassel-Baska, J., Zuo, L., Avery, L. D., & Little, C. A. (2002). A curriculum study of gifted-student learning in the language arts. Gifted Child Quarterly, 46(1), 30-44.https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620204600104

Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2018). An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

Vermunt, J. (1996). Metacognitive, cognitive and affective aspects of learning styles and strategies: A phenomenographic analysis. Higher Education, 31, 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00129106

Vermunt, J., & Donche, V. (2017). A Learning Patterns Perspective on Student Learning in Higher Education: State of the Art and Moving Forward. Educational Psychology Review, 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9414-6

Vermunt, J., Vrikki, M., van Halem, N., Warwick, P., & Mercer, N. (2019). The impact of Lesson Study professional development on the quality of teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.02.009

*Vogelaar, B., Resing, W. C. M., Stad, F. E., & Sweijen, S. W. (2019). Is planning related to dynamic testing outcomes? Investigating the potential for learning of gifted and average-ability children. Acta Psychologica, 196, 87-95.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2019.04.004

Vu, T., Magis-Weinberg, L., Jansen, B. R. J., van Atteveldt, N., Janssen, T. W. P., Lee, N. C., ..., & Meeter, M. (2021). Motivation-achievement cycles in learning: A literature review and research agenda. Educational Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09616-7

White, S., Graham, L. J., & Blaas, S. (2018). Why do we know so little about the factors associated with gifted underachievement? A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 24, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.03.001

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Bieke Finet and Marika Suetens for their support in specific stages of this study.

Funding

This work was funded by the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO), project number S002917N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The literature search and the data analysis were performed by Katelijne Barbier. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Katelijne Barbier, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author’s personal details

Katelijne Barbier. Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Training and Education Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Current themes of research:

High-ability students. Classroom environment. Teacher professional development.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Barbier, K., Struyf, E., & Donche, V. (2022). Teachers' beliefs about and educational practices with high-ability students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 1-12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103566

Barbier, K., Donche, V., & Verschueren, K. (2019). Academic (under)achievement of intellectually gifted students in the transition between primary and secondary education: An individual learner perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(2533). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02533

Elke Struyf. Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Training and Education Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Current themes of research:

Teacher professional development. Classroom or school environment. Student–teacher relationships.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Barbier, K., Struyf, E., & Donche, V. (2022). Teachers' beliefs about and educational practices with high-ability students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 1-12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103566

Lavrijsen, J., Dockx, J., Struyf, E., & Verschueren, K. (2021). Class composition, student achievement, and the role of the learning environment. Journal of Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000709

Van Mieghem, A. & Struyf, E. & Verschueren, K. (2020). The relevance of sources of support for teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs towards students with special educational needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1829866.

Karine Verschueren. Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, School Psychology and Education in Context, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Current themes of research:

Child and adolescent development in schools. The role of student–teacher and peer relationships. High-ability students’ development.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Ramos, A., Lavrijsen, J., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Sypré, S. & Verschueren, K. (2021). Profiles of maladaptive school motivation among high-ability adolescents: A person-centered exploration of the motivational pathways to underachievement model. Journal of Adolescence, 88, 146- 161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.03.001.

Lavrijsen, J. & Vansteenkiste, M. & Boncquet, M. & Verschueren, K. (2021). Does motivation predict changes in academic achievement beyond intelligence and personality? A multitheoretical perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000666.

Lavrijsen, J., Dockx, J., Struyf, E., & Verschueren, K. (2021). Class composition, student achievement, and the role of the learning environment. Journal of Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000709.

Vincent Donche. Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, School Psychology and Education in Context, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Current themes of research:

Learning and instruction. Higher education. Educational measurement.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Barbier, K., Struyf, E., & Donche, V. (2022). Teachers' beliefs about and educational practices with high-ability students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 1-12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103566

Willems, J., Coertjens, L. & Donche, V. (2021). First-year students’ social adjustment process in professional higher education: Key experiences and their occurrence over time. European Journal of Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00530-8.

Vermunt, J. D., & Donche, V. (2017). A learning patterns perspective on student learning in higher education : state of the art and moving forward. Educational Psychology Review, 29(2), 269–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10648-017-9414-6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barbier, K., Struyf, E., Verschueren, K. et al. Fostering cognitive and affective-motivational learning outcomes for high-ability students in mixed-ability elementary classrooms: a systematic review. Eur J Psychol Educ 38, 83–107 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00606-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00606-z