Abstract

In educational contexts, interpersonal attributional theory (Weiner, 2019) posits that teachers’ beliefs about the causes underlying their students’ academic performance vary along the causal dimensions of locus of causality, stability, personal controllability, and others’ controllability. Based on this framework, this study aimed at identifying teachers’ attribution profiles based on their perceptions about the causes of their students’ achievements. Two hundred eighty-nine experienced and novice French primary school teachers reported their causal beliefs about a student’s success or failure at a reading test, as well as their emotional and behavioral reactions to their student’s outcome. The data were analyzed using latent profile analyses, which identified five teachers’ attribution profiles that varied on the four causal dimensions. The results showed that profile memberships were greatly determined by the student’s outcome valence: three teachers’ attribution profiles were especially related to failure and two additional profiles to success. Profile memberships were associated with various cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reactions in line with the interpersonal attributional theory of motivation. The powerless profile — high external and uncontrollable attributions — indicated the lowest level of helping behavior. The conscientious profile — high internal and controllable attributions — indicated the highest levels of pride and student’s responsibility. Overall, these results partially support Weiner’s interpersonal attributional theory of motivation using a person-centered approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Understanding perceptions of causality of academic success or failure, and their consequences, is of great importance for educational researchers and practitioners. On the one hand, causal attributions enable teachers and students to make sense of academic events occurring within the school environment. On the other hand, this causal interpretation has numerous consequences on students, teachers, and their everyday interactions. As a result, much research has been carried out in the last 50 years to investigate how students and teachers attribute causality in educational contexts and to identify the consequences of these attributions on achievement and achievement-related outcomes (Graham, 2020; Graham & Williams, 2009; Weiner, 1985, 1986, 1995, 2000, 2019).

Among the various models that have emerged over the years, Weiner’s attributional theory has become a leading approach to capture how both students and teachers causally explain academic success or failure and how they think, feel, and behave in response to such events (Weiner, 1979, 1985, 2000, 2005). Based on the seminal work of Heider (1958), this framework views causal attributions as cognitions that generate emotional and behavioral reactions as well as expectations about future events. Developed initially to understand the intrapersonal consequences of students’ causal attributions in achievement situations (Graham, 2020; Graham & Williams, 2009; Weiner, 1985, 1986, 2000), this theory has been extended to interpersonal contexts such as teacher-student interactions (Weiner, 1995, 2000, 2010; for a recent review see Wang & Hall, 2018). From this interpersonal perspective, teachers’ emotional reactions and behaviors following their students’ academic success or failure were shown to depend on their causal perceptions of this event (Weiner, 1995, 2006; Weiner & Kukla, 1970).

Although Weiner’s attributional theory has been extensively tested, especially in educational contexts, only recent research has focused on individual differences in causal attribution based on the underlying properties of the attributed causes (Osborne & Weiner, 2015). This paper extends this research to include the identification of various teacher causal attribution profiles which explain their students’ academic outcomes, as well as their predictors and their emotional, cognitive, and behavioral consequences.

Weiner’s interpersonal attributional theory of motivation

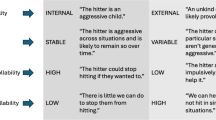

Weiner’s interpersonal attributional theory focuses on the observer’s attributions and their cognitive, emotional, and behavioral consequences for outcomes experienced by others (Weiner, 1995, 2000). According to this theoretical framework, the attribution sequence is initiated by an achievement experienced by a social agent (a student) in which the observer (the student’s teacher) is involved. This event triggers the observer’s causal search. Once the observer attributes a cause to the social agent’s outcome (student’s effort), this cause is characterized by its underlying dimensions, which are the locus of causality, stability, and control. The locus of causality dimension refers to the spatial location of the cause, whether inside (internal) or outside (external) the social agent. For instance, ability and effort are usually considered to be inside, whereas luck and the power of others are considered to be outside. The stability dimension refers to the duration of the cause, whether temporary and unstable or permanent and stable. Ability is usually considered as a stable cause, whereas chance is unstable. The control dimension relates to whether the cause is within the social agent’s volitional control or not. For instance, the ability is considered as an uncontrollable cause, whereas effort is a controllable cause. Although there is an agreement regarding the location of some causes within Weiner’s causal dimension space, some interpersonal differences could exist. For instance, the implicit theory of intelligence (Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Leggett, 1988) states that intelligence can be perceived as innate or as evolving through experiences.

The next stage concerns the consequences relative to the causal dimensions. The control dimension is of particular interest, as it determines the agent’s responsibility for his/her outcome, and it also plays a major role in the observer’s emotional and behavioral reactions. Indeed, the observer’s perception of the agent’s responsibility for the outcome is an important subcomponent, which was subsequently added to Weiner’s interpersonal theory. This concept was assumed to be strongly related to the causal dimensions, especially to the control dimension. For instance, previous research revealed that teachers perceived their students as more responsible for their failure when the students attributed their outcome to a lack of effort as opposed to a lack of ability. In this case, the teachers were more prone to experience higher levels of anger and reported higher levels of punishment than reward (Cooper & Burger, 1980; Matteucci, 2007; Matteucci et al., 2008; Weiner, 2000, 2001).

To sum up, Weiner’s interpersonal attributional theory assumes that teachers’ behaviors resulting from their students’ success or failure depend on the causal attributions (especially their underlying dimensional properties) that they use to explain this outcome. This theory also assumes that teachers’ emotional reactions and cognitive inferences (student’s responsibility perceived by the teacher) play a mediating role in the process (Reyna & Weiner, 2001; Weiner, 2006).

Teacher’s causal attributions for students’ outcomes

Various causal attributions can be produced by teachers to explain students’ success or failure at school. Research has shown that some of them are more common than others. Although some of these causes refer to the students’ internal properties, such as their level of ability or effort, other causes emphasize the role played by environmental factors, such as task difficulty or other’s helping behavior (Burger et al., 1982; Fennema et al., 1990; Georgiou et al., 2002; Hall et al., 1989; Holloway & Hess, 1985; Natale et al., 2009; Weiner, 1985, 1986). For instance, Burger et al. (1982) observed that elementary school teachers explained their students’ success more frequently by ability or regular effort—two causes considered as internal and stable—and their failures by immediate lack of effort or attention—two causes considered as internal but unstable. Jager and Denessen (2015) reported that Dutch secondary school teachers more frequently explained the lack of performance of low achieving students by internal causes, such as lack of attention, motivation, or effort, than by external causes, such as task difficulty or poor teaching.

However, although some studies showed that teachers could explain students’ failures by external causes (Bar-Tal & Guttmann, 1981; Bertrand & Marsh, 2015; Hall et al., 1989; Rolison & Medway, 1985), the overall picture indicates that teachers tend to mobilize mainly internal causes to explain academic failure (Hall et al., 1989; Jager & Denessen, 2015; Rolison & Medway, 1985; Tollefson et al., 1990). As far as academic success is concerned, research has shown that teachers tend to attribute their students’ successes to causes related to the high quality of their teaching (Gosling, 1994; Guskey, 1982; Kulinna, 2007; Yehudah, 2002) while also giving the students credit for their successes by using internal attributions (Natale et al., 2009; Wang & Hall, 2018).

On the whole, these results showed that teachers tend to explain students’ failures by referring to student characteristics (lack of effort) and not to causes relative to themselves (teaching strategies), whereas they tend to explain their students’ successes by referring to causes relative to themselves. For this reason, in their literature review, Wang and Hall (2018) concluded that teachers seemed to be subject to the hedonic bias (Miller & Ross, 1975).

Emotional and behavioral consequences of teachers’ causal attributions

As stated above, Weiner’s interpersonal attributional theory assumes that causal attributions provided by teachers to explain their students’ academic achievement impact their emotional reactions, which guide their behaviors toward these students. An abundant body of literature has highlighted these relationships in educational contexts. Indeed, teachers tended to feel more anger and disappointment when they attributed a student’s failure to his or her lack of effort, while they felt more empathy, pity, and despair when they attributed a student’s failure to his or her lack of skill (Butler, 1994; Georgiou et al., 2002; Weiner & Kukla, 1970; Woolfson & Brady, 2009). However, while findings regarding these other-directed emotions are well-documented in the literature, only a few studies examined the effect of these attributions on teachers’ self-directed emotional responses such as pride or guilt. For instance, Prawat et al. (1983) observed that American elementary school teachers reported high levels of pride and satisfaction when they explained their students’ achievements in terms of effort, mainly for low achievers. Teachers perceive their student’s success also as their own, especially when the teacher thinks he or she played a key role in the student’s success. On the other hand, teachers reported feeling high levels of guilt when they attributed the unexpected lack of effort to their students’ failures, particularly for competent students. In this case, teachers perceive their student’s failures also as their own, especially when they have reason to believe that they are responsible for this failure (inappropriate teaching method).

With regard to the behavioral consequences of teachers’ attributions, research has distinguished two types of behavior typical of teachers toward their students, namely, punishment/reward (feedback) behavior (Weiner & Kukla, 1970) and helping behavior (Tollefson & Chen, 1988). In particular, research has shown that teachers who attributed a student’s failure to low investment (lack of effort) gave more negative feedback and criticism and reported the intention to limit the help given to this student. On the other hand, following a causal attribution related to a student’s lack of ability, teachers encouraged the student, limited negative criticism, and reported the intention to help him/her (Butler, 1994; Cooper & Lowe, 1977; Matteucci et al., 2008; Reyna & Weiner, 2001; Tollefson & Chen, 1988; Woodcock & Jiang, 2013). Finally, teachers’ behaviors were shown to be directly influenced by inference of responsibility. For instance, Matteucci (2007) showed that the more a student is perceived by his or her teacher as being responsible for his or her failure, the more likely the teacher was to adopt punitive behaviors. On the other hand, a teacher who attributed the lack of ability to a student’s failure and perceived him/her as irresponsible for his/her performance intended to encourage and help the student. In the same vein, Reyna and Weiner (2001) found a mediating effect of perceived responsibility between the controllability dimension and the emotions of anger and sympathy felt by teachers. They also observed a mediating effect of these emotions on the relationship between perceived responsibility and punitive behavior.

Individual differences in teacher’s causal attributions

While much research conducted within the attributional framework has sought to establish relationships between causal attributions, emotional reactions, and behaviors, less research has been conducted to identify characteristics of students and teachers that could influence the type of attributions they produced (Wang & Hall, 2018). Research has shown that teachers’ causal attributions differed according to the gender of the student (Reyna, 2000). Indeed, teachers tended to explain boys’ performance in mathematics and girls’ performance in language with causal attributions related to student ability (Georgiou, 2008). Espinoza et al. (2014) and Fennema et al. (1990) observed that in the mathematics domain, teachers were inclined to attribute boys’ successes to their ability, and their failures to a lack of effort, whereas teachers showed the opposite tendency for girls, namely that they attributed their successes to effort, and their failures to a lack of ability.

Professional experience has also been shown to influence how teachers explained their students’ academic results. Indeed, those with more seniority tended to attribute student achievement more to external causes (family, socio-economic status) than novice teachers (Georgiou, 2008). When experienced teachers attribute internal causes, they were more likely to view student performance as due to uncontrollable and stable causes (trait-like ability) compared to novice teachers. Conversely, the latter gave more importance to their role and the students’ effort in their causal explanations (Georgiou, 2008). Pirrone (2012), who compared the causal attributions of inexperienced teachers (less than 10 years of experience) with those of highly experienced teachers (more than 30 years of experience), observed that highly experienced teachers tended to mobilize internal and uncontrollable causes (lack of student maturity) to explain the failure, whereas inexperienced teachers mobilized more external causes such as family circumstances (Reyna, 2000, 2008; Wang & Hall, 2018).

Research aim and hypotheses

Although a great deal of research has focused on teachers’ attributions of their students’ successes and failures, little research has focused on their underlying causal dimension patterns. In this research, we investigated distinct patterns underlying individual differences in teacher’s attributions for students’ academic performance, predictors of pattern membership, as well as their associated emotional and behavioral consequences. Using a person-centered approach, the first goal of this study was to identify distinct profiles underlying these individual differences in primary school teacher causal attributions for their students’ academic outcomes. The second goal was to examine how some predictors (event valence, student’s reading competence perceived by the teacher, student’s and teacher’s gender, and teacher’s seniority) relate to the profile memberships and to examine the extent to which the profiles differ on cognitive (expectancy of success and responsibility), emotional (shame, pride, guilt, hopelessness, pity, and anger), and behavioral (punitive or supportive) consequences specific to Weiner’s attributional theory.

Method

Participants

Two hundred eighty-nine volunteer primary school teachers from the south-east region of France took part in this study (86.32% female; mean seniority = 5.09 years, SD = 8.52). With the agreement of their supervisor, they were recruited by email. Before data collection, the participants were informed of the anonymity of the study, its main objectives, and what they would have to do.

Procedure

The participants were randomly assigned to an academic success condition (N = 162) or a failure condition (N = 127). In both conditions, they were asked to select one of their students whose school report showed a moderately successful academic performance. The French school report provides details about a student’s acquisition in each subject on the curriculum. The report given to the participants was designed to help them choose an average student in their class and also to provide them with information that would enable them to judge their students in line with research on social judgeability (Leyens et al., 1992). Having read the school report, the participants rated the student’s level of academic performance on an item. They were asked to choose a student in their class who best corresponded to the profile presented in the report and write the student’s initials and gender in the questionnaire. Then, just before completing each item on the questionnaire, the participants read an account of a fictitious classroom situation in which they had just returned the final reading test results to their students and their selected student’s test outcome was either a success or a failure. The reading domain was chosen for its importance at primary school (Dutrévis & Toczek, 2007).

Measures

Teachers’ causal beliefs

Teachers’ causal beliefs for their student’s reading test outcome were measured using the French version of the Causal Dimension Scale II (EMAC; Fontayne et al., 2003, McAuley et al., 1992). For the purpose of this study, the item wording was adapted to capture the teachers’ causal perceptions of the student’s performance on the reading test. The teachers reported the most important cause of their student’s outcomes. Then, they completed the CDSII. Using three items, this scale assessed each of the four causal dimensions in Weiner’s attributional theory (1985, 2000): locus of causality, stability, student’s personal control, and other’s control. Teachers had to indicate on nine-point scales whether the cause was internal or external to the student (locus of causality; − 4 = “reflects an aspect of this student”; 4 = “reflects an aspect of the situation”), temporary or persistent over time (stability; − 4 = “is stable over time”; 4 = “is variable over time”), potentially under the student control (personal control; − 4 = “is manageable by this student”; 4 = “is not manageable by this student”), and under other’s control (other’s control; − 4 = “is something over which others have control”; 4 = “is something over which others have no control”). Some item scales were reverse-coded to facilitate the interpretation of results: a high score for each dimension indicated a cause that was perceived as being highly internal within the student, stable, controllable by the student, or controllable by others, respectivelyFootnote 1.

Teacher’s cognitive reactions

Teacher perception of the student’s academic level

One item measured the perceived academic level of the student presented in the school report. It was worded as follows: “According to you, compared to a typical student, the academic level of this student is […].” The participants were asked to indicate the student’s academic level on an eleven-point scale ranging from 0 (very low level) to 10 (very high level).

Teacher perception of student’s responsibility

The teacher’s perception of his/her student’s responsibility for the outcome was measured with one item. It was worded as follows: “To what extent do you consider this student responsible for his/her outcome?” Teachers were asked to assess his/her student’s responsibility for their outcome on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (student not at all responsible for its reading outcome) to 9 (student totally responsible for its reading outcome). Higher scores indicate higher levels of student’s responsibility.

Teacher’s expectancy of student’s future success

The teacher’s expectancy of their student’s success was measured by one item designed specifically for the study. It was worded: “According to you, at the next reading test, this student’s result will be [...]” and asked the teacher to assess his/her student’s next test grade in reading on an 11-point scale ranging from − 5 (really worse than this one) to + 5 (really better than this one). High scores indicate a high expectancy of success.

Teacher’s emotional reactions

As observers, teachers feel different emotions in response to their students’ outcomes. Teachers’ emotions are self-directed when teachers have reason to believe that they played a key role in their students’ success or failure (pride, hopelessness, guilt, and shame). Teachers’ emotions can also be other directed. For example, teachers may be angry with a student when they think he or she failed due to a lack of effort. These two types of emotional reactions were each assessed by one item on a 9-point scale (1 = very mild; 9 = very strong). The teachers had to indicate the extent to which their students’ causal attribution for the outcome made them feel self-directed emotions (pride, hopelessness, guilt, and shame) and other-directed emotions (anger and pity). For example, one item was worded: “Taking into account the reason for the student’s poor test outcome, to what extent would you feel shame?” High scores indicate high levels of emotion.

Teacher’s behavioral reactions

Teacher’s behavioral reactions were measured regarding the level of reward/punishment they would give to the student given the performance obtained, as well as the level of helping behaviors they would provide. Reward/punishment behavior was measured with one item worded as follows: “To what extent would you praise or punish this student following his/her result?” The participants were asked to rate the extent to which they would praise or punish their student following his/her outcome on an 11-point scale ranging from − 5 (severe reprimands) to 5 (strong congratulations). Helping behavior was measured with four items. The participants were asked to rate to what extent they agreed to change their teaching behavior toward this student to help him more on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (not agree at all) to 9 (totally agree). One sample item was worded: “Now I will be more attentive to this student.” The internal consistency of this scale was satisfactory (ω = .80; McDonald, 1999).

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses comprised four stages and were conducted by using MPLUS software version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017). In the first stage, the factorial structure of the French version of the CDSII and its invariance across the success and failure conditions was first checked by means of confirmatory factorial analyses (CFA) and multigroup CFA. Several fit indices were used to evaluate the data adjustment of the models (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2004): Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimator was used to handle the somewhat non-normal data distributions (− .88 < γ1 < .66; − 1.12 < γ2 < − .08). Missing values (less than 3.4% per item, except student’s gender item: 6.2%) and missing completely at random, Little’s MCAR test: χ2 (687) = 701.89, p = .34), were handled with full information maximum likelihood (Dong & Peng, 2013; Enders, 2010). Factor scores on the four causal dimensions were extracted from the CFA (Morin, Boudrias, Marsh, Madore, & Desrumaux, 2016a; Morin, Boudrias, Marsh, McInerney, et al., 2016b) and used in the following analyses.

The second stage consisted of performing latent profile analyses (LPA) with factor scores extracted in the previous stage serving as indicators. Models including up to 6 profiles were estimated by using 5000 random sets of start values with 100 iterations each and the 100 best solutions retained for final stage optimizations to avoid settling on a local solution. Several statistical tests and indices were used to select the model with the optimal number of profiles (McLachlan & Peel, 2000): the Bayesian information criteria (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), the sample-adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC; Sclove, 1987), the Akaike information criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1973), the consistent Akaike information criterion (CAIC; Bozdogan, 1987), the standard and adjusted Lo et al.’s (2001) likelihood ratio tests (LRT), and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT; Nylund et al., 2007). Lower values on the AIC, CAIC, BIC, and SABIC indicate better model fit. The different LRTs consisted of comparing a k-profile model with a k-1-profile model. A significant p-value indicates that the k-profile model should be retained. As small number of cases in a profile could lead to unstable or bias parameter estimates, models including profiles with few cases were rejected. In addition, the posterior probabilities of profile membership and entropy value (the closer the value is to 1 the more precise the classification) were used to determine classification accuracy (Lubke & Muthén, 2007). Finally, the theoretical meaning of the profiles was also used to determine the best solution to retain (Bauer & Curran, 2004).

The third stage consisted of performing the LPA model with covariates (Vermunt, 2010). As full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data on covariate was not available for this kind of model, the multiple imputation method was used (Rubin, 1987; Schafer, 1997).

The fourth and final phase consisted of testing the model retained with distal continuous outcome variables. Using BCH procedure (Bolck et al., 2004), significant mean differences of distal continuous variables across the profiles were tested (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014; Bakk & Vermunt, 2016).

Results

Preliminary analyses of the French CDSII factor structure

As expected, the CFA four-factor model had a good fit to the data (χ2 = 75.00, ddl = 48, RMSEA = .04, IC 90% = .02–.06, SRMR = .05, CFI = .97, TLI = .96) with four well-defined factors (| λ | = .83–.63, M = .76). The reliability was satisfactory for each subscale (locus of causality (ω = .79), stability (ω = .85), personal control (ω = .82), and other’s control (ω = .76). The invariance test of the French CDSII structure between the success and failure conditions supported metric invariance and partial strong invariance (the locus of causality item 1 intercept was not invariant, see supplementary materials).

Latent profile identification

Latent profile analyses were conducted on factor scores extracted from the CFA model. The results obtained showed that a five-profile model could be considered as the most satisfactory oneFootnote 2. Indeed, even the AIC, BIC, and SABIC continued to decrease with the addition of one profile in the tested model, these decreases were weak as in the five-profile model. The CAIC reached its lowest value in the five-profile model (Table 1). Although the BLRT was not useful for selecting the optimal solution given that it was always significant, the LRT and Adjusted LRT p-values were significant at 10% thresholds up to five profiles. Moreover, the number of participants classified in the lowest profile was too small to be meaningful for the six-profile model (N = 12).

In addition, the five-profile model showed a satisfactory level of entropy (.82). The average posterior probabilities of class membership in the target profile varied from .85 to .95 (M = .89), with low cross probabilities (.00–.09, M = .04), indicating a satisfactory level of classification accuracy (Table 2). Moreover, univariate entropy values indicated that the locus of causality and the student’s personal control dimensions contributed more toward the profile differentiation than stability and others’ control (univariate entropy values were .54, .53, .13, and .19, respectively).

Latent profile interpretation

Figure 1 depicts the five student profiles. Profile 1, which included around 10% of the teachers (N = 28), was labeled powerless and was characterized by a highly external locus of causality (M = − 3.29, SE = .32), instability (M = −.40, SE = .24), a very low personal control (M = − 4.46, SE = .39), and low others’ control (M = − 1.09, SE = .32). Profile 2, which included around 18% of the participants (N = 52), was labeled as vulnerable since it was defined by an external locus of causality (M = − 2.43, SE = .35), a somewhat low stability (M = − .73, SE = .15), a somewhat low personal control (M = − .57, SE = .23), and a high others’ control (M = .85, SE = .17). Profile 3, which was composed of around 13% of the participants (N = 37), was labeled fatalistic given that it was characterized by a neutral locus of causality (M = − .06, SE = .36), marginally above average stability (M = .53, SE = .28), low personal control (M = − 2.10, SE = .35), and low others’ control (M = − 1.17, SE = .32). Profile 4, labeled self-starter, included around 38% of the teachers (N = 109) and was characterized by a very low internal locus of causality (M =.41, SE = .18), neutral stability (M = − .05, SE = .12), personal control (M = .77, SE = .17), and neutral others’ control (M = .14, SE = .13). Profile 5, composed of around 22% of the participants (N = 63), was labeled conscientious and characterized by a high internal locus of causality (M = 2.75, SE = .25), a marginally above average stability (M = .55, SE = .16), a high personal control (M = 2.30, SE = .27), and a neutral other’s control (M = .22, SE = .15; Tables 2 and 3).

Profile membership predictors

Predictors of profile memberships including event valence, student’s reading competence perceived by the teacher, student’s gender, teacher’s gender, and teacher’s seniority, were added to the five-profile model. The results from the multinomial logistic regressions showed that a positive event increased by five times the probability of belonging to the conscientious profile, as opposed to the powerless and the fatalistic profiles. Moreover, the probability of belonging to the self-starter profile rather than the vulnerable profile was higher for a positive event. The odds ratio indicated that a positive event tripled the probability of belonging to the self-starter profile compared to the vulnerable profile.

To sum up, teachers who were placed in the success condition described the cause of their student’s outcome that corresponded more to profiles 4 (the self-starter profile) and 5 (the conscientious profile), whereas teachers placed in the failure condition described their cause that corresponded more to profiles 1 to 3 (the powerless, vulnerable, and fatalistic profiles, respectively).

An effect of the teacher’s gender was found. The probability of belonging to profile 1 (the powerless profile) compared to profile 2 (the vulnerable profile) was higher for male than female teachers (B = − .97, SE = .50, p = .055; odds ratio = .38). The odds ratio indicated that being a male teacher doubled the odds of belonging to profile 1 compared to profile 2. Finally, lower seniority tendentially decreased the probability of belonging to profile 1 compared to profile 3 labeled fatalistic (B = − .04, SE = .03, p = .096; odds ratio = .96). No significant effect for student’s gender and student’s reading competence perceived by the teacher was found in the results (Table 4).

Distal outcomes

Teacher’s perceived responsibility

The mean levels of student’s responsibility perceived by the teacher varied across the different profiles, χ2 (4) = 106.77, p = .00. Teachers belonging to profile 5 reported the highest levels of student’s responsibility for his/her outcome (MConscientious = 7.08, SE = .22), followed by those who belong to Profile 4 (MSelf-starter = 5.84, SE = .16), whose two levels were significantly higher than those from the other three profiles which showed no significant differences between them (MPowerless = 4.55, SE = .44, MVulnerable = 4.11, SE = .26, MFatalistic = 4.48, SE = .31, profiles 1, 2, and 3; Table 5).

Expectancy of success

The mean levels of expectancy of success tendentially varied across the different profiles, χ2 (4) = 8.20, p = .09. Teachers belonging to profile 3 reported the lowest expectancy of success (MFatalistic = 1.06, SE = .37) compared to those from profiles 2, 4, and 5 (MVulnerable = 2.47, SE = .31, MSelf-starter = 1.95, SE = .17, MConscientious = 2.02, SE = .26, respectively). No other differences were found (Table 5).

Emotions

Overall, the mean levels of self-directed emotions (shame, pride, guilt, and hopelessness) varied across the different profiles (χ2 (4) = 24.80, p = .00; χ2 (4) = 20.55, p = .00; χ2 (4) = 19.40, p = .00; and χ2 (4) = 9.36, p = .05, respectively) but not those of other-directed emotions (anger and pity). Teachers belonging to profile 5 reported lower levels of shame (MConscientious = 1.09, SE = .07) compared to the other four profiles (MPowerless = 2.12, SE = .39, MVulnerable = 2.05, SE = .29, MFatalistic = 1.67, SE = .29, MSelf-starter = 1.55, SE = .15, respectively profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4). They also felt higher levels of pride (MConscientious = 4.97, SE = .44) than other profiles (MPowerless = 3.11, SE = .54, MVulnerable = 2.46, SE = .37, MFatalistic = 3.47, SE = .55, MSelf-starter = 3.62, SE = .31, respectively profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4). Furthermore, profile 4 teachers reported higher levels of pride (MSelf-starter = 3.62, SE = .31) than those belonging to profile 2, MVulnerable = 2.46, SE = .37. Regarding hopelessness, teachers belonging to profile 5 reported lower levels (MConscientious = 1.28, SE = .11) than those belonging to profiles 1 and 2 (MPowerless = 2.09, SE = .37, and MVulnerable = 1.90, SE = .30, respectively). No other differences were significant. Finally, participants belonging to profile 2 reported higher levels of guilt (MVulnerable = 3.82, SE = .43) than those belonging to the other profiles (MPowerless = 2.51, SE = .39, MFatalistic = 2.43, SE = .37, MSelf-starter = 3.33, SE = .23, MConscientious = 1.77, SE = .22, respectively profiles 1, 3, 4, and 5). No other difference was found to be statistically significant (Table 5).

Sanction and helping behaviors

The mean levels of helping behavior varied across the different profiles, χ2 (4) = 10.62, p = .03. Teachers belonging to profile 1 reported the lowest levels of helping behavior (MPowerless = 5.95, SE = .38) compared to the other profiles (MVulnerable = 7.40, SE = .24, MFatalistic = 6.99, SE = .28, MSelf-starter = 6.99, SE = .16, MConscientious = 7.18, SE = .21, respectively profiles 2, 3, 4, and 5). No other differences were found regarding teachers’ helping behavior. Moreover, the results indicated no mean differences between profiles for the teachers’ sanction behavior (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined population heterogeneity in primary school teachers’ causal beliefs about students’ academic outcomes within Weiner’s interpersonal attributional theory.

The latent profile analyses identified five distinct profiles of attributional patterns. Thirty-eight percent of teachers attributed a causal pattern to their student outcomes that we labeled the self-starter profile (low internal locus of causality, neutral stability, student’s control, and neutral other’s control). Then, 21.8% of teachers attributed a pattern to the student outcomes that we labeled the conscientious profile (high internal locus of causality, highly under student’s volitional control, and somewhat stable and under other’s control). Next, 18% attributed a pattern to the student outcomes that we labeled the vulnerable profile (high external locus of causality, somewhat unstable and uncontrollable, but somewhat under other’s control). Then, 12.8% explained their student outcomes as belonging to the fatalistic profile (neutral locus of causality, somewhat stable, and outside student’s and other’s control). Finally, 9.6% attributed a pattern to the student outcomes that we labeled the powerless profile (high external locus of causality outside student’s control, and somewhat outside other’s control).

The analysis results also showed that the event valence clearly differentiated between the profiles according to the positivity or negativity of the outcome. Indeed, a negative event greatly increased the probability of belonging to the powerless, vulnerable, fatalistic, and self-starter profiles rather than the conscientious profile. When a negative event occurs, the vulnerable profile is also more likely than the self-starter profile. These results were contrary to those which show that teachers are more likely to attribute student failure to causes that are internal to the students themselves (Jager & Denessen, 2015; Tollefson et al.’s, 1990). Indeed, our results were more in line with studies that found that teachers tend to attribute students’ failure to external and uncontrollable causes—powerless and vulnerable profiles (Bar-Tal & Guttmann, 1981; Bertrand & Marsh, 2015; Hall et al., 1989; Rolison & Medway, 1985). Our study shows that the participants perceive the causes of student failures as external to the students themselves and beyond their control. However, causes of students’ successes were more likely to be perceived as internal and under the student’s volitional control. These results were in line with studies that suggest that teachers give credit to students for their successes and differed from those showing that teachers tend to take credit for their students’ successes (Guskey,1982; Natale et al., 2009; Yehudah, 2002).

Concerning the relationships between the profiles and predictors, the results were rather unclear. Teacher’s gender predicted profile membership and male teachers were more likely to describe a student that corresponded to the Powerless profile than to the conscientious or the vulnerable profiles. These results should be interpreted with caution due to the overrepresentation of female teachers in our sample. Student’s gender, teachers’ seniority, and teachers’ perception of the student’s competence had no significant effect on profile membership. The teachers did not consider boys and girls to correspond to different student profiles in the reading domain. This finding differed from those indicating that teachers believe that boys have more ability in math and girls have more ability in language, and therefore, that teachers generally attribute girls’ success in math to effort (internal, unstable, controllable), whereas boys’ success in math is usually attributed to ability (internal, stable, uncontrollable). Girls’ failure in math is often attributed to a lack of ability, while boys’ failure in math is normally attributed to a lack of effort (Espinoza et al., 2014; Fennema et al., 1990; Georgiou, 2008). Furthermore, the teachers’ seniority effect was not significant. This did not support research findings which show that experienced teachers display a stronger tendency to attribute students’ outcomes to causes that are external to the students themselves and beyond their control. Our findings did not reveal the stronger tendency of experienced teachers to attribute students’ failure to causes that are internal and uncontrollable. Furthermore, our results did not confirm the research that found that novice teachers attribute students’ outcomes to external causes, such as family environment (Georgiou, 2008; Pirrone, 2012). As expected and based on the experimental induction, the teachers’ perception of the student’s competence had no significant effect. Since the target was described as having an average level of academic performance, this result confirmed that teachers had a similar perception of the academic competence of the student they had selected.

Finally, the results indicated that the profiles related differently to the key outcome variables specific to Weiner’s attributional theory. They showed differences between profiles in the student’s responsibility for their outcome as perceived by the teacher. Teachers belonging to the conscientious profile considered their student to be the most responsible, followed by those from the self-starter profile, and teachers who belong to the powerless, vulnerable, and fatalistic profiles perceived their students as being the least responsible for their outcomes. These results partially support the attribution of responsibility theory (Weiner, 1995, 2006). According to Weiner’s theory, the extent to which teachers perceive students as personally responsible for their outcomes is influenced by the cause they attribute to the student’s outcome. For instance, Matteucci (2007) and Matteucci et al. (2008) showed teachers perceived their students to be more responsible for their failure when they attribute it to lack of effort rather than lack of ability. The dimensions of locus of causality and controllability play key roles in the attribution process. The more the cause is perceived as being controllable and internal to the student, the more responsible the teacher judges their student to be (Weiner, 1995). This corresponds to the attributional pattern of the conscientious profile (high internal locus of causality and strong student’s control) and may explain why teachers who belong to this profile perceived their students as being fully responsible for their outcome. Likewise, teachers belonging to the powerless, vulnerable, and fatalistic profiles, characterized by an external locus of causality and/or student uncontrollability, reported low student responsibility.

As suggested by Weiner’s theory, more stable causes lower expectancy of success, whereas unstable causes heighten it, especially following a failure. The results support these findings (Weiner, 2000). In contrast with the unstable pattern of the vulnerable profile, the stable pattern of the fatalistic profile could explain why these teachers are less optimistic about their student’s future success.

Weiner’s theory suggests that teachers’ emotions are affected by the causes they perceive behind their students’ outcomes (Weiner, 1995, 2000, 2010). Our results showed clear differences in emotional responses. For example, teachers who belong to the conscientious profile reported the lowest levels of shame and hopelessness and the highest level of pride. They felt the lowest levels of less adaptive emotions (shame and hopelessness) for their student’s future success, resulting in a belief that their students would not do better in the future and that there was nothing they could do about it (Weiner, 1985, 1995, 2000). Another interesting result was that teachers belonging to the vulnerable profile felt a high level of guilt in reaction to their students’ outcomes. This was not surprising as they perceived the cause of their student’s outcome as being external and uncontrollable by the student but under other’s control including themselves.

Teachers belonging to the powerless profile reported the lowest level of helping behavior. The attributional pattern of this profile is characterized especially by a high external locus of causality, high student’s uncontrol, and other’s uncontrol. This could be interpreted as a kind of resignation—teachers considered that they feel unable to help these students whether directly (teaching strategies) or indirectly (intervene with the family). This result is somewhat different from Weiner’s results, which showed that the lowest level of helping behavior was linked to causes relative to effort characterized as inside the student, unstable, and under volitional student’s control, meaning that if the student wanted to, they could do better. Our results also showed no differences in sanction behavior between the profiles. French teachers seemed to be cautious about negative sanctions following their students’ negative results. This was in line with Weiner’s theory, they did not often consider the causes of this failure as being under their student’s control thereby limiting their perceived responsibility and thus the justification for sanctions (Weiner, 1995, 2000, 2006). These results confirmed that teachers could explain their students’ outcomes differently, but in limited ways, and that the profiles differed on some emotional and behavioral consequences. In addition, the participants tended to give credit to their students for their successes and perceived their students as not being responsible for their failures. Importantly, combining LPA, direct measure of causal dimensions, and the choice of a typical student allowed us to identify teachers’ prototypical attributional patterns underlying the causes they attributed to the most common student outcomes. It is worth mentioning that students received less help from teachers who belong to the powerless profile, which could be detrimental to their future success. This is in line with Weiner’s interpersonal attributional theory which suggests that teachers’ causal beliefs influence their emotions and instructional behaviors, and this may influence students’ academic outcomes (Weiner, 1995, 2000, 2006).

However, this study has some limitations worth mentioning. First, fictitious reading test outcomes were used and this could have diminished the teachers’ commitment and emotional responses. Second, several measures were single-item scales to limit the data collection duration and encourage teacher participation. Future studies should use multi-item scales to measure teacher’s reactions as well as measures that do not rely only on self-report methods. Third, this study is transversal and correlational. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the stability/instability over time and the causal direction between the causal dimension profiles and their cognitive, emotional, and behavioral consequences. For instance, Upadyaya et al.’s (2012) results showed reciprocal effects between teachers’ causal attributions and students’ motivation concepts. Finally, this study focused on teachers’ attributions to the reading outcomes of typical students. Future studies may examine teachers’ causal beliefs for low or high-skilled students’ outcomes in reading and/or other domains.

Conclusion

While many studies have focused on teachers’ attributional beliefs about students’ academic outcomes within Weiner’s attributional theory, to date no study has combined the direct measure of causal dimensions and latent profile analysis. In doing this, we were able to identify a number of teacher profiles based on their attributional beliefs about typical students’ academic outcomes. Our results demonstrated that these distinct latent profiles are determined by the outcome valence and that these profiles affect the teachers’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reactions, which play a vital role in student achievement. To conclude, this study provides further insight into the complex mechanisms involved in teachers’ causal beliefs about students’ academic outcomes and how they shape their reactions.

Notes

Reliability information of the four subscales of the CDSII is reported in the “Results” section.

See supplementary materials for LPA conducted on failure and success conditions separately. The results are similar.

References

Akaike, H. (1973). Maximum likelihood identification of Gaussian autoregressive moving average models. Biometrika, 60(2), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/60.2.255.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181.

Bakk, Z., & Vermunt, J. K. (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.955104.

Bar-Tal, D., & Guttmann, J. (1981). A comparison of teachers’, pupils’ and parents’ attributions regarding pupils’ academic achievements. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 51(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1981.tb02488.x.

Bauer, D. J., & Curran, P. J. (2004). The integration of continuous and discrete latent variable models: Potential problems and promising opportunities. Psychological Methods, 9(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.9.1.3.

Bertrand, M., & Marsh, J. A. (2015). Teachers’ sensemaking of data and implications for equity. American Educational Research Journal, 52(5), 861–893. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831215599251.

Bolck, A., Croon, M., & Hagenaars, J. (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mph001.

Bozdogan, H. (1987). Model selection and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika, 52(3), 345–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294361.

Burger, J. M., Cooper, H. M., & Good, T. L. (1982). Teacher attributions of student performance: Effects of outcome. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 8(4), 685–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167282084013.

Butler, R. (1994). Teacher communications and student interpretations: Effects of teacher responses to failing students on attributional inferences in two age groups. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 64(2), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1994.tb01102.x.

Cooper, H. M., & Burger, J. M. (1980). How teachers explain students’ academic performance: A categorization of free response academic attributions. American Educational Research Journal, 17(1), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312017001095.

Cooper, H. M., & Lowe, C. A. (1977). Task information and attributions for academic performance by professional teachers and roleplayers. Journal of Personality, 45(4), 469–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1977.tb00165.x.

Dong, Y., & Peng, C.-Y. J. (2013). Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-222.

Dutrévis, M., & Toczek, M.-C. (2007). Perception des disciplines scolaires et sexe des élèves : le cas des enseignants et des élèves de l’école primaire en France. L’Orientation Scolaire et Professionnelle, 36(3), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.4000/osp.1469.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford.

Espinoza, P., da Luz Fontes, A. B. A., & Arms-Chavez, C. J. (2014). Attributional gender bias: Teachers’ ability and effort explanations for students’ math performance. Social Psychology of Education, 17(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9226-6.

Fennema, E., Peterson, P. L., Carpenter, T. P., & Lubinski, C. A. (1990). Teachers’ attributions and beliefs about girls, boys, and mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 21(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00311015.

Fontayne, P., Martin-Krumm, C., Buton, F., & Heuzé, J. P. (2003). Validation française de la version révisée de l’échelle de mesure des attributions causales (CDSII). Les Cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie Sociale, 58, 59–72.

Georgiou, S. N. (2008). Beliefs of experienced and novice teachers about achievement. Educational Psychology, 28(2), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410701468716.

Georgiou, S. N., Christou, C., Stavrinides, P., & Panaoura, G. (2002). Teacher attributions of student failure and teacher behavior toward the failing student. Psychology in the Schools, 39(5), 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10049.

Gosling, P. (1994). The attribution of success and failure: The subject/object contrast. European journal of psychology of education, 9(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172886.

Graham, S. (2020). An attributional theory of motivation. An attributional theory of motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101861.

Graham, S., & Williams, C. (2009). An attributional approach to motivation in school. In K. R. Wenzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Educational psychology handbook series. Handbook of motivation at school (p. 11–33) Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Guskey, T. R. (1982). Differences in teachers’ perceptions of personal control of positive versus negative student learning outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 7(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(82)90009-1.

Hall, B. W., Villeme, M. G., & Burley, W. W. (1989). Teachers’ attributions for students’ academic success and failure and the relationship to teaching level and teacher feedback practices. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 14(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(89)90031-3.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relationships. Wiley.

Holloway, S. D., & Hess, R. D. (1985). Mothers’ and teachers’ attributions about children’s mathematics performance. Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children, 177–199.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jager, L., & Denessen, E. (2015). Within-teacher variation of causal attributions of low achieving students. Social Psychology of Education, 18(3), 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9295-9.

Kulinna, P. H. (2007). Teachers’ attributions and strategies for student misbehavior. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 42, 21–30.

Leyens, J.-P., Yzerbyt, V. Y., & Schadron, G. (1992). The social judgeability approach to stereotypes. European Review of Social Psychology, 3(1), 91–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779243000032.

Lo, Y., Mendell, N., & Rubin, D. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778.

Lubke, G., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Performance of factor mixture models as a function of model size, covariate effects, and class-specific parameters. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(1), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510709336735.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2.

Matteucci, M. C. (2007). Teachers facing school failure: The social valorization of effort in the school context. Social Psychology of Education, 10(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-006-9011-x.

Matteucci, M. C., Tomasetto, C., Selleri, P., & Carugati, F. (2008). Teacher judgments and pupils’ causal explanations: Social valorization of effort-based explanations in school context. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 23(4), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172750.

McAuley, E., Duncan, T. E., & Russell, D. W. (1992). Measuring causal attributions: The revised Causal Dimension Scale (CDSII). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(5), 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292185006.

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum.

McLachlan, G., & Peel, D. (2000). Finite Mixture Models. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471721182.

Miller, D. T., & Ross, M. (1975). Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin, 82(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076486.

Morin, A. J. S., Boudrias, J.-S., Marsh, H. W., Madore, I., & Desrumaux, P. (2016a). Further reflections on disentangling shape and level effects in person-centered analyses: An illustration exploring the dimensionality of psychological health. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(3), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2015.1116077.

Morin, A. J. S., Boudrias, J.-S., Marsh, H. W., McInerney, D. M., Dagenais-Desmarais, V., Madore, I., & Litalien, D. (2016b). Complementary variable- and person-centered approaches to the dimensionality of psychometric constructs: Application to psychological wellbeing at work. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(4), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9448-7.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén &Muthén.

Natale, K., Viljaranta, J., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Nurmi, J. E. (2009). Cross-lagged associations between kindergarten teachers’ causal attributions and children’s task motivation and performance in reading. Educational Psychology, 29(5), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903165912.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396.

Osborne, D., & Weiner, B. (2015). A latent profile analysis of attributions for poverty: Identifying response patterns underlying people’s willingness to help the poor. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.007.

Pirrone, C. (2012). The influence of teachers’ preexisting notions about students on scholastic achievement. AASA Journal of Scholarship and Practice, 9(2), 18–28.

Prawat, R. S., Byers, J. L., & Anderson, A. H. (1983). An attributional analysis of teachers’ affective reactions to student success and failure. American Educational Research Journal, 20(1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312020001137.

Reyna, C. (2000). Lazy, dumb, or industrious: When stereotypes convey attribution information in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 12(1), 85–110. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009037101170.

Reyna, C. (2008). Ian is intelligent but Leshaun is lazy: Antecedents and consequences of attributional stereotypes in the classroom. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 23(4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172752.

Reyna, C., & Weiner, B. (2001). Justice and utility in the classroom: An attributional analysis of the goals of teachers’ punishment and intervention strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(2), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.2.309.

Rolison, M. A., & Medway, F. J. (1985). Teachers’ expectations and attributions for student achievement: Effects of label, performance pattern, and special education intervention. American Educational Research Journal, 22(4), 561–573. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312022004561.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley & Sons.

Schafer, J. L. (1997). Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. Chapman & Hall, London. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439821862.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136.

Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02294360.

Tollefson, N., & Chen, J. S. (1988). Consequences of teachers’ attributions for student failure. Teaching and Teacher Education, 4(3), 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(88)90005-4.

Tollefson, N., Melvin, J., & Thippavajjala, C. (1990). Teachers’ attributions for students’ low achievement: A validation of Cooper and Good’s attributional categories. Psychology in the Schools, 27(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199001)27:1<75::AID-PITS2310270111>3.0.CO;2-%23.

Upadyaya, K., Viljaranta, J., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Nurmi, J. E. (2012). Cross-lagged relations between kindergarten teachers’ causal attributions, and children’s interest value and performance in mathematics. Social Psychology of Education, 15(2), 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-011-9171-1.

Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpq025.

Wang, H., & Hall, N. C. (2018). A systematic review of teachers’ causal attributions: Prevalence, correlates, and consequences. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02305.

Weiner, B. (1979). A theory of motivation for some classroom experiences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.71.1.3.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.92.4.548.

Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. Springer-Verlage. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4948-1.

Weiner, B. (1995). Judgments of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct. Guilford Press.

Weiner, B. (2000). Intrapersonal and interpersonal theories of motivation from an attributional perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009017532121.

Weiner, B. (2001). An attributional approach to perceived responsibility. In Responsibility: The many faces of a social phenomenon, eds A. E. Auhangen and H. W. Bierhoff (New York, NY: Routledge), 49–60.

Weiner, B. (2005). Motivation from an attribution perspective and the social psychology of perceived competence. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of Competence and Motivation (pp. 73–84). The Guilford Press.

Weiner, B. (2006). Social motivation, justice, and the moral emotions. Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410615749.

Weiner, B. (2010). The development of an attribution-based theory of motivation: A history of ideas. Educational psychologist, 45(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903433596.

Weiner, B. (2019). My journey to the attribution fields. In Advances in motivation science (Vol. 6, pp. 185-211). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2018.08.002

Weiner, B., & Kukla, A. (1970). An attributional analysis of achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029211.

Woodcock, S., & Jiang, H. (2013). Teachers’ causal attributional responses of students with learning disabilities in China. Learning and Individual Differences, 25, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.01.016.

Woolfson, L. M., & Brady, K. (2009). An investigation of factors impacting on mainstream teachers’ beliefs about teaching students with learning difficulties. Educational Psychology, 29(2), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802708895.

Yehudah, Y. B. (2002). Self-serving attributions in teachers’ explanations of students’ performance in a national oral essay competition. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 30(4), 411–415. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2002.30.4.411.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author’s personal details

Laurent Brun. Université Grenoble Alpes, LaRAC, Grenoble, France. Post-box: Université Grenoble Alpes, 1251 Avenue Centrale, 38400, Saint-Martin-d’Hères, bâtiment Michel Dubois, Aile C. Email: laurent.brun@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

Current Themes of Research:

Laurent Brun is PhD in Educational Sciences at Grenoble Alpes University (France). His research focuses on causal attribution and their cognitive and behavioral consequences in educational settings.

Most Relevant Publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Brun, L., Dompnier, B., & Pansu, P. (2019). Une échelle de mesure des attributions causales pour enfants : EMAC-E. L’Année psychologique, 119(4), 449-471. 10.3917/anpsy1.194.0449

Benoît Dompnier. Quartier UNIL-Mouline, Bâtiment Géopolis, Bureau: 5528, CH-1015, Lausanne, Switzerland. Email: Benoit.Dompnier@unil.ch

Current Themes of Research:

Benoît Dompnier is a Senior lecturer at University of Lausanne. His academic work concerns social psychology and educational psychology. His recent work focused on social judgment, self-presentation strategies and motivation in educational contexts.

Most Relevant Publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Świątkowski, W., & Dompnier, B. (2020). A regulatory focus perspective on performance goals’ effects on achievement: A small-scale meta-analytical approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 78.

Carrier, A., Dompnier, B., & Yzerbyt, V. (2019). Of nice and mean: The personal relevance of others’ competence drives warmth perceptions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45, 1549-1562.

Darnon, C., Wierderkehr, V., Dompnier, B., & Martinot, D. (2018). “Where there is a will, there is a way”: Belief in school meritocracy and the social-class achievement gap. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57, 250-262.

Jury, M., Darnon, C., Dompnier, B., & Butera, F. (2017). The social utility of performance-approach goals in a selective educational environment. Social Psychology of Education, 20, 215-235.

Verniers, C., Martinot, D., & Dompnier, B. (2016). The feminization of school hypothesis called into question among junior and high school students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 369-381.

Dompnier, B., Darnon, C., Meier, E., Brandner, C., Smeding, A., & Butera, F. (2015). Improving low achievers’ academic performance at university by changing the social value of mastery goals. American Educational Research Journal, 52, 720-749.

Dompnier, B., Darnon, C., & Butera, F. (2013). When performance-approach goals predict academic success and when they do not: A social value approach. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52, 587-596.

Dompnier, B., Darnon, C., & Butera, F. (2009). Faking the desire to learn: A clarification of the link between mastery goals and academic achievement. Psychological Science, 20, 939-943.

Pascal Pansu. Université Grenoble Alpes, LaRAC, Grenoble, France. Post-box: Université Grenoble Alpes, 1251 Avenue Centrale, 38400 Saint-Martin-d’Hères, bâtiment Michel Dubois, Aile C. Email: pascal.pansu@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

Current Themes of Research:

Pascal Pansu, PhD in social psychology, is full Professor at Grenoble Alpes University (France). His research mainly focuses on social beliefs and social judgment and their effect on self-evaluation and cognitive performances. He investigates the dynamics and processes involved in learning and achievement in educational settings, as for example, how teacher judgment and evaluative indices present in the classroom regulate students’ self-perceptions, learning, and performance.

Most Relevant Publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Sanrey, C., Bressoux, P., Lima, L. & Pansu, P. (accepted). The halo effect in teachers’ judgments: Does certainty raise the bias? British Journal of Educational Psychology.

Boissicat, N., Pansu, P., & Bouffard, T. (2020). Does classroom social comparison bias students’ evaluation of their own competence? Social Psychology of Education, 1-24. DOI: 10.1007/s11218-020-09582

Hascoët, M., Pansu, P., Bouffard, T., & Leroy, N. (2018). The harmful aspect of teacher conditional support on students’ self-perception of school competence. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(4), 615-628. DOI: 10.1007/s10212-017-0350-0

Pansu, P, Régner, I, Max, S., Cole, P., Nezlek, J. B, & Huguet, P. (2016). A burden for the boys: Evidence of stereotype threat in boys’ reading performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 26–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2016.02.008

Bressoux, P., & Pansu, P. (2016). Pupils’ self-perceptions: The role of teachers’ judgment controlling for big-fish-little-pond effect. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(3), 341-357. DOI: 10.1007/s10212-015-0264

Bédard, K., Bouffard, T., & Pansu, P. (2014). The risks for adolescents of negatively biased self-evaluations of social competence: The mediating role of social support. Journal of adolescence, 37(6), 787-798. DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.05.004

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brun, L., Dompnier, B. & Pansu, P. A latent profile analysis of teachers’ causal attribution for academic success or failure. Eur J Psychol Educ 37, 185–206 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00551-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00551-3