Abstract

Background and Objective

The market for heated tobacco products (HTPs) has grown markedly in recent years, and many governments have started to tax HTPs to regulate their use. To evaluate the impacts of HTP taxes on tobacco use behaviors and health consequences, we first need to assess if they effectively raise HTP prices in a tax system that also taxes cigarettes. This study jointly evaluates the pass-through of taxes to prices of HTPs and cigarettes.

Data and Methods

We use a unique database on statutory HTP and cigarette taxes and retail prices of Marlboro-branded heated tobacco units and cigarettes from 2014 to 2021, developed by the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, in all countries where HTPs are sold. To estimate the pass-through of taxes to prices, we employ a seemingly unrelated regressions model. We also use an event study to test the impact of introducing HTPs to cigarette markets, as well as amending tax codes to include HTPs, on prices and price gaps.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Currently, the debate over whether HTPs should be taxed in comparison with cigarettes considers their potential harm reduction impact, and most countries tax HTPs at much lower rates than cigarettes in order to keep HTP prices lower than cigarette prices. However, the direct pass-through rate of HTP taxes to prices is several times smaller than that of cigarettes, resulting in very similar unit prices of HTPs and cigarettes. Further, while cigarette taxes are over-shifted to cigarette prices, HTP taxes are under-shifted to HTP prices, suggesting that tax gaps between the two products does not translate to price gaps. The results overall suggest that the lower taxes on HTPs do not lead to lower prices as compared to cigarettes and are unlikely to incentivize cigarette smokers to transition to HTPS for lower costs. Under this scenario, taxing both products equivalently could be an option to raise additional tax revenue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Heated tobacco products (HTPs) are tobacco products marketed by cigarette manufacturers as a substitute for cigarettes that might reduce the harms of tobacco to users in the short term, but their long-term health impacts are unclear [1, 2]. Nonetheless, HTPs are not harmless and could have the undesired effects of attracting youth and young adults to tobacco use or prolonging addiction among users who would otherwise quit tobacco or nicotine products altogether. Worldwide, HTPs have entered markets in a growing number of countries in recent years. The majority of HTP brands are manufactured and marketed by tobacco companies that also produce cigarettes. For example, the first and most popular brand of HTPs is IQOS heating devices, used with HEET sticks that are branded as Marlboro in a number of countries, which was introduced by Phillip Morris International (PMI) in Japan in 2014. Since then, other large tobacco multinationals have followed by producing their own brands, including British American Tobacco with GLO (used with Neo or Kent heat sticks), Japan Tobacco International’s Ploom Tech (used with Mevius heat sticks), and KT &G’S Lil (used with Fiit heat sticks). Nonetheless, as of 2020, PMI remains the leading manufacturer of HTPs, capturing 82% of the global market of HTPs.Footnote 1 Since its launch, the sales of HTPs have increased significantly in the world, with large volumes sold in Japan, Korea, and Italy, among others (Fig. 1). The increasing presence of HTPs in the tobacco market has posed challenges to regulators and policymakers in places where they are sold. Similar to other products that may pose less short-term harm than cigarettes but may prolong addiction and attract youth and young adults, there is a debate among the public health community and policymakers about whether HTPs should be taxed at a lower rate and regulated in a less restrictive manner compared to cigarettes [3, 4]. Policymakers also face challenges in choosing proper tax bases for HTPs: some countries impose taxes by sticks or packs, whereas other countries impose taxes by product weight.

According to the model of taxing cigarettes and other substances and the law of demand, taxing HTPs to make them less affordable could be the most effective policy to control the use of HTPs. In addition, taxing products based on their relative harms could incentivize consumers to switch from a higher-priced and more harmful product to a lower-priced, less harmful product. Although there is no conclusive evidence that HTPs can help smokers to completely quit smoking, taxing HTPs at a lower rate is being considered by policymakers if they indeed are substitutes for cigarettes. Thus far, several countries have employed different tax structures, types of tax, or tax rates to tax HTPs. In Europe, tax rates vary across countries and can be defined based on weight, number of sticks, retail prices, or consumption time. In Japan, since HTPs were included in the tax code in 2018, the effective HTP tax rates per stick have been increasing over time. In the US, although HTP are currently banned from being imported into the US, the FDA has nonetheless approved PMI’s IQOS as “modified-risk tobacco products,” which could have significant implications on HTP taxation if the ban is removed in the future. For example, Connecticut adopted a guideline to tax products approved by the FDA as in the “modified-risk tobacco products” category (e.g., Swedish Match snus and IQOS) at half the rate of an equivalent quantity of cigarettes.

The effectiveness of tax policies to regulate HTPs ultimately depends on how taxes are passed to prices (i.e., whether taxes sufficiently raise prices). Taxes could be under-shifted (i.e., a tax increase of $1 increases the price by less than $1), exactly-shifted (a $1 tax increase leads to a $1 price increase), or over-shifted (i.e., a tax increase of $1 increases the price by more than $1). This is because the supply side or manufacturers may respond to tax increases differently, depending on their market power and profit maximization incentives. In theory, the over-shifting of taxes to prices is linked to imperfectly competitive markets [5]. Evidence shows that the cigarette market can be categorized as oligopoly, where the few large tobacco companies have the market power to increase prices more than tax increases driven by the incentive to generate profits for shareholders [5,6,7]. Empirical evidence to this day has focused on evaluating the direct pass-through effect of cigarette taxes to prices and has mostly focused on high-income countries. Though this literature is still emerging, there is some evidence that taxes can be either under- or over-shifted to cigarette prices. The pass-through of taxes to prices is likely to vary across brands and depends on many other market characteristics, including the ability for companies to introduce (or dismiss) new (existing) brands/segments, the ability to practice stock-piling, or regulations regarding promotions [8].

Given that the large tobacco companies also control the HTP market, it is likely that they will strategically respond to HTP taxes and set prices to maximize profits from both the cigarette and the HTP markets. In other words, companies’ responses to HTP taxes also depend on how they make decisions on cigarette prices and respond to cigarette taxes. From observational evidence, and as confirmed by our data, PMI sets prices for HTP sticks, or heated tobacco units (HTUs) at the same level as equivalent quantities of comparable cigarettes (i.e., per pack of 20 sticks). There is evidence that the marginal input costs of HTU are similar to cigarettes. In its reports to investors, PMI states that the growth rate of net-revenue per HTU sold has quadrupled from 0.9% in 2018 to 3.7% in 2021, while that of cigarettes has decreased every year. In 2021, net revenue per HTU sold was four times larger than net revenue per unit sold of cigarettes.Footnote 2 In a highly concentrated market as is the case for HTPs, if HTPs generate large profits per unit (i.e., large profit margins), tobacco companies have an incentive to absorb all or part of cigarette tax increases to keep HTU prices similar to cigarette prices. They may also increase HTP prices higher than a tax increase to increase marginal profits. More generally, if companies’ intention in aligning the prices of HTPs and cigarettes is to reduce price competition between the two products, they may raise cigarette prices in response to HTP taxes and vice versa. These industry tactics could further vary by markets and reflect the different market shares that each company has of the cigarette market. In case companies’ cigarette market share is low, they may price HTP lower than cigarettes in order to take over market shares from competitors. However, if companies are leaders in the cigarette market, HTPs may be launched as a defensive strategy to maintain market shares and competitiveness. The companies may also have incentives to keep HTP and cigarette prices similar when facing regulation uncertainties. With all these potential scenarios, it is critical to test these hypotheses or scenarios using empirical data and ascertain how tobacco manufacturers set product prices in response to the introduction of HTP taxes in tax systems or tax increases (i.e., how taxes are passed to prices or tax pass-through rate).

Moreover, as a growing number of countries have introduced taxation for HTPs or are in the process of imposing taxes, it is important to assess the tax pass-through rate to better inform policymakers on the effectiveness of HTP taxes - a new regulation in many countries. The empirical evidence will also address the debate over whether tobacco taxes should be designed in a way to reflect products’ relative harms, in which system HTPs will be taxed at a lower rate than cigarettes. This rationale only stands when the tax gap between HTPs and cigarettes leads to a substantial price gap that will subsequently incentivize smokers to switch from cigarettes to HTPs completely. Studying how tax gaps lead to price gaps will thereby provide the necessary evidence to better inform countries on whether to impose differential tax rates for HTPs and cigarettes.

This study fills an important research gap by evaluating whether tax policy incentives that impose lower taxes on new products relative to cigarettes are effective at promoting HTPs to substitute for cigarettes. It assesses if differential taxation undermines or supports the impacts of nicotine or tobacco taxes in reducing tobacco consumption. To do this, we examine how HTP and cigarette taxes are passed to IQOS’s heat sticks and cigarette prices worldwide using PMI price data and unique HTP tax data that we collect, further employing an economic model that simultaneously considers taxes and prices for both products. Given that PMI’s HTP products are the market leader and big tobacco companies tend to adopt similar pricing strategies, we expect our results to be generalizable to other HTP and cigarette producers. The main findings are that the tax gap between HTPs and cigarettes is under-shifted to the price gap, implying that low HTP taxes are unlikely to result in lower HTP prices and encourage consumers to substitute combustible cigarettes with HTPs.

This paper is structured as follows. Section “Data” describes the data collected for this study. Section “Empirical Methodology” describes our empirical approaches to estimate the pass-though of taxes. Sections “Results” and “Discussion” present and discuss the results, and section “Conclusion” concludes.

Data

Taxes and Prices

The tax and price data are obtained from the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (CTFK, 2021), which collected a large database on excise and sales taxes and tax systems for heated tobacco products and cigarettes, along with pricing information, for all countries where heated tobacco products were sold from 2014 to 2021. As of February 2021, the database covered a total of 54 countries with HTP sales from all continents. The tax information was obtained from tax codes, tax laws and amendments, and regulation releases issued by countries’ regulatory or tax agencies (e.g., Tax Administrations, Bureau of Finance, Customs). Price information was obtained for the most sold brand of heated tobacco sticks and its most comparable cigarette brand.

As previously mentioned, countries’ tax systems vary along several dimensions, including the types of taxes (specific excise, ad-valorem, minimum excise, mixed systems), the definition of the tax base for these taxes, and whether tax rates are uniform or heterogeneous between products. For instance, the specific tax could be based on weight, the number of sticks, consumption time, or more complex volume bases. The ad-valorem tax could be based on the final retail price or the ex-factory price. The existing literature suggests that the two ways to compare taxes are 1) converting ad valorem taxes and taxes based on weight to taxes per stick; and 2) imputing tax incidence or burden as a percentage (%) of retail prices. To standardized taxes across countries, we calculated the total amount of excise taxes (not including the VAT) paid per stick in local currency terms, including all types of excise taxes and implied tax incidence. If taxes were changed in the middle of a year, we calculated effective tax rates using the number of months of each tax rate as weights to obtain annual average taxes. The resulting HTP and cigarettes tax database contains the tax implementation dates and historical changes in tax structures from 2014 onward, as this marks the year when IQOS was first launched in Japan. The tax bases are also standardized in ways that make them comparable between products and countries. As PMI’s IQOS Marlboro-branded HEETS are by and large the most-sold brand of heated tobacco products in the world, we use this brand for heated tobacco products in most countries, and the prices of equivalent quantities of comparable cigarettes brands, usually Marlboro, per pack of 20.Footnote 3 From this database, we also calculated the gap between cigarette excise taxes and HTP excise taxes.Footnote 4

To obtain a database that is comparable across countries, we converted all tax and price information from local currencies to purchasing power parity (PPP) values, which was obtained from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook [9].Footnote 5 More details about the data can be found on CTFK’s website [10], including an interactive global mapping tool, showing each country’s tax regulations and sources.

Other variables and controls

We construct the gap between cigarette and IQOS tax incidence as a simple difference between tax burdens (i.e., cigarette tax incidence-IQOS tax incidence). We collect time-varying measures that could impact prices, including Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (in log terms), GDP growth rate, and Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Table 1 presents a summary of the data used in the regression analysis. The database is an unbalanced panel of 57 countries and 13 Canadian provinces over 8 years from 2014 to 2021, representing 301 country-year observations. The average price of heated tobacco products (prhtp) is PPP $7.98, just PPP $1.5 below that of cigarettes (prcig), at PPP $9.5, and even though the average total tax amount (taxhtp) is PPP $1.78, more than 3 times smaller than the total excise tax on cigarettes, at PPP $4.9 (taxcig). The average gap between cigarettes and heated tobacco total excise taxes is PPP $3.1, more than one-third of the average price of cigarettes. We further decompose the excise tax gaps into specific excise tax gaps and ad valorem excise tax gaps. As most countries currently apply only specific excise taxes on heated tobacco based on the weight–at the same levels as pipe tobacco taxes– the large excise tax gap between heated tobacco sticks and cigarettes is essentially due to the small specific excise tax applied to heated tobacco sticks. As a result, the specific excise tax gap (taxgap_spe) between the two products is sizable, at PPP $2.1 on average. The ad valorem tax gaps are relatively smaller, at ppp $0.98.

Empirical methodology

We follow the rich literature that estimates the impacts of taxes on prices using a two-way fixed effects model, which can be summarized using the following equations:

Where Price and Tax represent the prices and taxes per pack of 20 sticks of heated tobacco products or cigarettes in country i and year t, converted into purchasing power parity values. \(\beta _1\) and \(\gamma _1\) (respectively \(\beta _2\) and \(\gamma _2\)) estimate the tax pass-through rates of a pack of heated tobacco (respectively for cigarettes) sticks to prices. The regressions also control for a set of country-specific macroeconomic indicators, denominated by vector Z_it, including GDP per capita (in logarithm form) and a full set of year and country fixed effects. Clustered standard errors are estimated to account for inter-temporal correlation within a country over time. We estimate these equations jointly using seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) to account for the fact that prices for HTPs and cigarettes are decided jointly, hence that equations (1) and (3) are likely correlated [11, 12]. SUR produces more efficient estimates than POLS by weighting the estimates by the covariance of the residuals.

To better understand the magnitude of the pass-through effect of different types of excise taxes to prices, we also estimate the tax impacts by separating specific taxes from ad-valorem taxes.

To further assess the validity of the industry’s claim that less restrictive regulations, or no regulations, on “reduced-risk” heated tobacco products will encourage smokers to quit cigarettes by providing a price incentive on switching to heated tobacco, we also estimate the pass-through of the tax gap between cigarettes and HTPs. That is, the impact of the tax gap on the price gap between cigarettes and HTPs, specified in the following equation

Where \(Gap^{Pr}\)represents the difference between cigarettes and HTP prices, and \(Gap_{it}^{Tax}\) represents the difference between the total excise tax on cigarettes and HTPs.

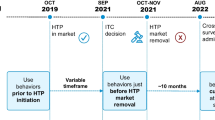

We also test the existence of parallel trends prior to the implementation of HTP taxes. When HTPs are first sold on a market, these products are not explicitly covered in a country’s tax code. Instead, they are automatically taxed as the category of “other tobacco products” in the majority of countries. This event results in HTP sticks being taxed at the same rates as products such as “pipe tobacco”, based on weight resulting in much lower tax rates than cigarettes. Appendix Table 5 shows the list of 70 countries included in this analysis (57 countries and 13 Canadian provinces) including provinces) and the tax policies they employ for heated tobacco products. Among them, 10 countries have not modified their tax codes to include HTPs during the period 2014-2021; hence there is no event year because the first year when HTP prices are observed coincides with the year when they are taxed as “other tobacco”. In other words, in these countries, there is no “pre-trend” in the price of HTPs as the first tax event year coincides with the first year when HTPs are observed on the market.

Nevertheless, the majority of the countries covered modified their tax systems to include HTPs shortly or a few years after the year when the product was introduced in their markets. For example, in Armenia, when HTPs entered the market in 2018 (column 7 of Appendix Table A1), they were systematically taxed under the category of “other tobacco products”. The tax system was changed in 2020 when HTPs were introduced in a separate category and taxed based on the number of sticks, yet not at the same tax rates as cigarettes. In the Canadian province of British Columbia, when HTPs appeared on the market in 2016, they were taxed by default as pipe tobacco. The tax authority introduced HTPs in a separate category in 2020, taxing them using the same tax base and rates as cigarettes. Although most countries covered in this study have introduced HTPs in their tax codes, the majority still tax them at much lower rates than cigarettes. As of 2021, of the 70 countries and provinces included in this research, only 12 tax HTPs equivalently to cigarettes. In a few countries, HTPs were initially taxed at a zero rate for a few years (Israel, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Philippines, Poland, South Africa) and started to be taxed at positive rates in recent years.

To evaluate whether these tax reforms affect the price incentive towards switching tobacco use from cigarettes to HTPs, our first event is defined as the first year when HTPs were introduced into the tax code as an independent category. This event can effectively increase (or not) the tax on HTPs, such as in cases where the new tax is set to be higher than pipe tobacco or equivalent to cigarettes.

Then we estimate an event study as presented in [13], as a two-way fixed effect model for the overall level of excise taxes and prices.

Where \(\mu _i\) and \(\tau _t\) are country and year fixed effects, \(X'_{it}\) are time-varying country controls, and \(\epsilon _{it}\) is the error term. The lags and leads are binary variables referring to the number of periods (years) away from the event of interest and defined as follows:

The final lags and leads accumulate lags or leads beyond periods J or K. The first lag or lead is automatically omitted to capture the baseline difference between locations where the event occurs or not. In addition, we evaluate whether this event-the inclusion of HTPs in countries’ tax codes and the introduction of a specific tax category for them-impacts the price of cigarettes, and the gap between cigarettes and HTP prices, using a similar event study as described by equation (4).

Results

Table 2 shows the SUR estimates of tax pass-through rates to the prices of packs of HEET sticks and cigarettes using a variety of specifications. As SUR simultaneously estimates the model for heated tobacco and cigarettes, each set of two columns shows the results of equations (1) and (3), respectively. The first two specifications (1) and (2) show the direct pass-through of a product’s excise taxes to the product price, while the next two specifications (3) and (4) show the indirect effect of a product’s excise taxes on the other product’s price. Specifications (1) and (3) separate the specific and ad-valorem excises, while specifications (2) and (4) show the total excise tax pass-through to prices.

We find that a 1 PPP dollar increase in HTP taxes leads to a 31.4 cents increase in heated tobacco prices (Column 3) whereas a one-dollar increase in cigarette taxes leads to a 1.1 dollar increase in cigarette prices (column 4). Both the specific and ad-valorem excise tax impact the prices of heated tobacco, with a pass-through rate of the ad-valorem tax about 3 times larger than the pass-through rate of the specific tax (column 1).

Both the specific tax and the ad-valorem cigarette taxes significantly impact the price of cigarettes by 0.99 and 1.4, respectively (column 2). We find no evidence of overall cross-price effects (specification (4), in columns 7 and 8), though the ad-valorem tax on cigarettes positively affects the price of HTPs (specification (3), column 5).

Overall, these results reveal that while HTP taxes are under-shifted to heated tobacco prices, cigarette taxes are slightly over-shifted to cigarette prices. Cigarette taxes also seem to be shifted to heated tobacco products, but with offsetting effects of each type of excise, with an overall effect remaining insignificant.

Table 3 reports the results of SUR models estimating the simultaneous effects of heated tobacco and cigarette excise taxes on tobacco product prices in specifications (1) and (2), and allows for the combined effect of the products’ taxes by including interaction terms in specifications (3) and (4). Specifications (1) and (3) show results that separate the two types of excise taxes by bases, while specifications (2) and (4) show results based on the full excise term. The results confirm that the overall pass-through of HTP taxes to HTP prices is small (column 3, around 0.31), while the pass-through of cigarette taxes to cigarette prices is larger than 1 (column 4, around 1.1).

Interestingly, while specification 2 suggests that there are no cross-product tax impacts (i.e., HTP taxes do not influence cigarette prices or vice versa), the more flexible specifications (3 and 4) show that there are cross-product tax impacts after controlling for the interaction between cigarette and HTP taxes. Given that cigarette taxes have been around for decades and are an important policy context for HTP taxes, we focus on the discussion of the flexible specifications (3 and 4) that allow cigarette taxes to moderate or mediate HTP tax impacts on prices and vice versa. As the WHO FCTC advocates for raising cigarette taxes continuously to keep up with inflation, the flexible specifications also better capture this dynamic.

The results reveal that the prices of cigarettes and heated tobacco products are simultaneously impacted by the taxes of both products. For example, specification (4) shows that when the total excises on each product simultaneously increase by 1 dollar, the price of HTPs decreases, though not significantly (column 7), and the price of cigarettes increases by 3.4 cents (column 8). We also examined whether the cross-product effects of taxes on the other product’s price are moderated or mediated by own taxes. Indeed a PPP$ 1 increase of HTP taxes reduces the price of cigarettes by 17 cents, and a PPP$ 1 increase in cigarette taxes increases cigarette prices by 94 cents. Likewise, the specification in column (7) reveals that after controlling for the interaction between cigarette and HTP taxes, a PPP$ 1 increase in HTP taxes raises HTP prices by 57 cents; and that a PPP$ 1 increase in cigarette taxes raises HTP prices by 31 cents. These findings suggest cross-product tax impacts on each other’s prices after considering the moderation impacts of own taxes.

The results in Table 3 support that HTP taxes are under-shifted to HTP prices, while cigarette taxes are over-shifted to cigarette prices - the conclusion we reached based on results in Table 2. In addition, we found cross-product tax impacts - increases in HTP taxes would reduce cigarette prices, whereas increases in cigarette taxes would increase HTP prices. This indicates that the prices of HTPs and cigarettes are jointly determined by tobacco companies and policy environments.

When we estimate the impacts of the tax gap between cigarettes and HTP excises on the price gaps between the products in PPP values and percentage points (Table 4), we find that the overall excise tax gap between cigarettes and HTPs is under-shifted to the price gap between cigarettes and heated tobacco, with a pass-through rate of the nominal tax gap of about 0.54. The tax burden gap, or incidence gap does not influence the price gap, except for the tax burden gap of the ad-valorem tax (column 4 of Table 4). This finding complements the findings from Table 3 and shows that companies set HTP prices such that they align with cigarette prices, even when the gap in excise taxes between the two products increases.

The results of the event study described in Eqs. (5) and (6) are shown in Fig. 2. The event year captures the first year when a country first amended the tax code to introduce HTPs in a separate tax category. There is no event year in countries where HTPs are not explicitly defined in the tax code. With this event study specification, the coefficients for the lag terms can provide evidence of different pre-trends in cigarette prices, HTP prices, and price gap (cigarette minus HTP prices), between the treatment and comparison groups. If coefficients on the lags are small in magnitude and statistically insignificant from zero, this suggests that the parallel trends assumption is supported and that the two-way fixed effect model (or Differences-in-Differences) estimates the causal impact of introducing HTP products in tax codes on outcomes. Moreover, the event leads indicators capture the dynamics of outcome trends post the inclusion of HTPs in tax codes, or the delayed impacts of introducing HTPs in tax codes to impact outcomes. As expected, Figure 2 shows that there were no differential pre-trends in cigarette prices or post-policy dynamics prior to including HTPs in tax codes. We find no evidence of significant change in the trends of cigarette or HTP prices after the event. There is evidence of an increased variation across countries in both cigarette and HTP prices after the events. Also, HTP prices tend to decrease on average post events, as compared to before the events, but this change is not significantly different from zero. For price gaps between cigarettes and HTPs, there is evidence of significant differential pre-trends, but the post-event trends in price gaps are not significantly different from zero. This suggests that introducing HTPs in tax codes has reduced the price gap between the two products by a small amount, yet large enough to close the gap between the prices of the two products. Moreover, as the lags of HTP introduction do not impact future HTP prices, we did not find evidence for price smoothing or those companies slowly raising prices in response to taxes in order to avoid a hike in prices.

We conducted another event study based on the first year when HTPs were introduced in markets to indirectly investigate the possibility that HTPs are strong substitutes for cigarettes and that, as a result, when smokers or potential smokers have access to them, they might substitute cigarettes with HTPs. If this is correct, we should see an impact on cigarette prices as the demand for cigarettes decreases. Alternatively, if tobacco companies are indeed committed to harm reduction as they claim to be, we may see them increase cigarette prices in order to move smokers from cigarettes to HTPs. Figure 3 shows no significant reactions of cigarette prices to the introduction of HTPS in tobacco markets, nor the existence of pre- or post- differential trends in cigarette market prices. Nevertheless, the overall cigarette excise taxes (inclusive of specific and ad-valorem excises) significantly increase in response to the introduction of HTPs to the tobacco market. This increase in cigarette excise taxes seems to be essentially driven by the ad-valorem taxes since the specific excise does not change significantly in any year pre- or post- the introduction of HTPs into the markets. Given that ad-valorem tax rates or tax bases have not been modified in most countries over the period, the increase in overall excise taxes suggests that cigarette prices may have increased as a response to the introduction of HTPs, subsequently increasing ad-valorem tax payments and overall cigarette excise taxes. Finally, these results alone suggest a substitution effect between the products. More research is needed to evaluate the impacts of HTPs introduction and price differentials on the demands of heated and combustible tobacco products.

Discussion

Economic theory suggests that, by setting taxes based on relative harms, policies could create a price or cost incentive for consumers to switch to the cheaper product. We found that while the existing tax burden on HTPs is lower than that on cigarettes in most countries, the prices of the two products are very similar. In other words, the tax gap between the two products does not sufficiently raise price gaps and may fail to incentivize cigarette smokers to transition completely to HTPs. Further, although our empirical model is based on the assumption that cigarettes and HTPs are substitutes, there is a lack of conclusive evidence that HTPs are effective in assisting smokers to quit. Under this scenario, setting HTP taxes lower than cigarette taxes will unlikely achieve the desired public health benefits.

Given similar marginal costs of producing heated tobacco sticks, our evidence implies that under certain market conditions, such as having a oligopoly power over two related products, the direct pass-through of taxes to prices can be much smaller for the low-taxed product (heated tobacco) than for the high-taxed product (cigarettes), signaling that companies extract large profit margins from the low-taxed. Therefore, the impacts of taxes on the demand for low-taxed products are likely to be non-significant because of minimal price shifts. As a result, tax incentives that favor HTPs to cigarettes are unlikely to be effective policy tools to encourage smokers to substitute them to combustible products, implying that these policies are likely to generate less tax revenues for governments but large extra profit margins for companies compared to policies that set equivalent tax rates between these products.

We use data from 70 countries (including 13 Canadian Provinces) during the 2014-2021 period to estimate the model jointly for HTPs and cigarettes, considering that their prices are set by manufacturers (mostly large tobacco companies) to maximize profits. Our results show that both cigarette and HTP taxes are passed to HTP and cigarette prices, but the pass-through rates are much lower for HTP taxes (0.31) than cigarette taxes (1.09), which confirms the model’s assumption that companies that manufacture both products respond to excise taxation policies by extracting large profit margins from heated tobacco products. It is critical for policymakers to evaluate how HTPs are taxed in comparison to cigarettes.

The finding that the direct pass-through effect of taxes is much smaller for HTPs than for cigarettes, while cigarette taxes are over-shifted to cigarette prices, and while the prices of both products are similar, suggests that companies raise substantial additional profits from heated tobacco products. The finding that the total excise tax gap between cigarettes and HTPs positively affects cigarette prices confirms this presumption. Meanwhile, although the absolute tax gaps influence price gaps, the tax burden gap (difference in the % rates) does not significantly impact the price gap. As a result, the evidence does not support the goal of using smaller tax burdens for HTPS than cigarettes (i.e., lower taxes per units of HTPs than cigarettes) to create economic incentives for smokers to “quit” cigarette smoking.

Using our estimated tax pass-through rates, we are able to project what would happen if countries make a one-time adjustment and impose equal taxes on cigarettes and HTPs. As Table 1 suggests, the current excise tax rates are at $1.78 for HTPs and $4.9 for cigarettes, with a difference of $3.12. If governments close the tax gap between HTPs and cigarettes and raise the HTP taxes by $3.12, the average HTP price will increase by $0.96 to $8.94, still lower than the average cigarette price, which is at $9.46. If the tax pass-through rate remains stable for both cigarettes and HTPs, and both products experience the same amount of tax increases, the price difference between the two products will continue to grow as the HTP tax pass-through rate is much lower than cigarette tax pass-through rate.

Further research should evaluate the impacts of new tobacco products’ and conventional cigarettes’ prices on their respective demands. Indeed as cigarettes continue to be the core or primary product in tobacco companies’ revenue, the demand for cigarettes may not decrease as much because 1) tobacco companies can reduce the pass-through of cigarette taxes to prices by raising additional profit margins from new products while keeping their price just below that of cigarettes to increase new products’ demand. Our results show that HTP tax rates are relatively low compared to cigarettes and under-shifted to prices. Even if HTP taxes are adjusted to the same level as cigarette taxes, the average HTP prices will still be lower than cigarettes. Moreover, the differential tax pass-through rates that are higher for cigarettes than for HTPs will make cigarettes more expensive than HTPs as taxes continue to grow over time. Therefore, whether differential taxes are necessary to maintain the incentive for smokers to switch is debatable. Under this scenario, although we acknowledge the potential benefit of differential taxes based on relative harms, policymakers may want to generate tax revenues by raising HTP taxes.

Policymakers also need to evaluate their goal when setting HTP taxes. If the goal is to prevent youth and young adult non-cigarette users from initiating HTPs, the rationale for providing a cost incentive for smokers to switch may make sense. However, the findings from this paper reveal that setting heated tobacco taxes lower than cigarette taxes may not result in a sizable price gap between the two products while raising companies’ profit margins. Currently, although HTP prices are slightly lower than cigarette prices, tobacco companies set and maintain the two prices very closely. We project that, with a low tax pass-through rate for HTPs, if instead governments HTPs and cigarettes equivalently, cigarette prices will remain higher than HTP prices, and governments would raise additional revenue.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the database remains relatively small as HTPs are not yet distributed in many countries. Nevertheless, our data contain both cross-country and time variation. They also include within-country variation in countries where local governments impose their own sales and excise taxes, such as in Canada. Second, the limited time span of our data to 8 years prevents us from controlling for unobserved country effects that vary simultaneously over periods and between countries (which would require country-year fixed effects). Instead, we use a two-way fixed effects model. Third, the data are for PMI products: IQOS’ HEET sticks and Marlboro cigarette prices. Although this could be a limitation on the representation of the markets, PMI remains a market leader in both markets, and the data are more comparable across countries than using other brands of heat sticks.Footnote 6 Fourth, we do not control for the influences of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products on HTP or cigarette prices. Fifth, we assume that tobacco companies’ ultimate goal is to maximize profits for shareholders. Therefore, we did not consider their stated commitment to harm reduction. Their stance may change in the future if HTPs or other reduced-harm products account for a significant share of their revenues. Lastly, we do not have enough variations to disentangle the impacts of different tax bases, such as weights vs. sticks. Future studies could address these limitations.

Conclusion

Theoretically, taxing HTPs at a lower rate than cigarettes could make HTPs more economically attractive than cigarettes by encouraging firms to sell HTPs at lower prices than cigarettes, thereby incentivizing smokers to substitute HTPs for cigarettes. However, we find that HTP taxes are under-shifted to prices. Moreover, in spite of differential taxation, companies set similar prices for cigarettes and HTPs, which leads to a lower tax incidence for HTPs and generates more profits for tobacco companies to manufacture and sell HTPs. In other words, the tax difference or tax burden gap between cigarettes and HTPs does not translate into a sizable cost difference between the two products for consumers. Therefore, differential tax rates based on relative harms between cigarettes and HTPs will unlikely incentivize smokers to quit smoking using HTPs. Moreover, the WHO FCTC recommends countries to continuously increase cigarette taxes overtime to keep up with inflation, indicating that there likely are rooms to increase HTP taxes. Under this scenario, policymakers may use HTP taxes to achieve the tax revenue generation goal instead of the health promotion goal and may consider taxing HTPs at a higher rate to generate more tax revenues.

Availability of data and material

A link to some of the data is provided in the paper. Access to programs and full databases can be made available upon request and consent of confidentiality.

Notes

Phillip Morris International Investor Information, March 2021

For instance, PMI reports total adjusted net revenues per unit (including the shipments of cigarettes and HTUs) of 5.7% for the year 2021 and a compound annual growth rate of net revenue per unit of 6.7% since 2018. The company further reports that the performance of net revenue per unit has been driven by the increasing proportion of heated tobacco units in PMI’s sales mix.

In some countries, HEETS sticks are not the most sold brand of HTPs, or Marlboro cigarettes are not in circulation. In such cases, we replace HEETS with the most sold brand and its closest cigarette equivalent. For example, in the Canadian province of Ontario, HEETS is not the most sold brand of HTPs, but its closest comparable cigarette is Belmont 25’.

More information on the methodology, including the conversion weights (from grams to sticks), and relevant sources, can be found on CTFK’s website.

The purchasing power parity indicator is the “Implied PPP conversion rate” (variable PPPEX).

We checked the robustness of the results to the exclusion of observations where HEETS and Marlboro are not the most sold brand (Canada), and found that this exclusion has no significant impact on the estimates.

References

Akiyama, Yukio, Sherwood, Neil: Systematic review of biomarker findings from clinical studies of electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products. Toxicol. Rep. 8, 282–294 (2021). (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214750021000147)

McKelvey, Karma, Baiocchi, Michael, Halpern-Felsher, Bonnie: Pmi’s heated tobacco products marketing claims of reduced risk and reduced exposure may entice youth to try and continue using these products. Tobacco Control 29(e1), e18–e24 (2020). (https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/29/e1/e18)

Jun, J., Kim, S.-H., Thrasher, J., Cho, Y.J., Heo, Y.-J.: Heated debates on regulations of heated tobacco products in south korea: the news valence, source and framing of relative risk/benefit. Tobacco Control, (2021). https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2021/02/04/tobaccocontrol-2020-056131

Liber, Alex C.: Heated tobacco products and combusted cigarettes: comparing global prices and taxes. Tobacco Control 28(6), 689–691 (2019). (https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/28/6/689)

Besley, Timothy J., Rosen, Harvey S.: Sales taxes and prices: an empirical analysis. Natl. Tax J. 52(2), 157–178 (1999)

Berthet, ValdoisJ., Walbeek, Corne Van, Ross, Hana, Soondram, Hema, Jugurnath, Bhavish, Sun, MarieChan, Mohee, Deowan: Tobacco industry tactics in response to cigarette excise tax increases in mauritius. Tobacco Control 29(e1), e115–e118 (2020). (https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/29/e1/e115)

Rosemary, H.P., Timea, R., Gilmore, A.B., Branston, J.R., Hitchman, S., McNeill, A.: Impact of tobacco tax increases and industry pricing on smoking behaviours and inequalities: a mixed-methods study. Number 8.6. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library, Apr (2020). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555634

Sheikh, Z.D., Branston, J.R., Gilmore, A.B.: Tobacco industry pricing strategies in response to excise tax policies: a systematic review. Tobacco Control, (2021)

International Monetary Fund (IMF). World economic outlook, October (2020). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Heated tobacco products and cigarettes taxes and prices around the world, (2021). https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/what-we-do/global/taxation-price/tax-gap

Cameron, A., Trivedi, P.: Microeconometrics Using Stata, Revised Edition. StataCorp LP, (2010)

Zellner, Arnold: An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 57(298), 348–68 (1962). (http://www.jstor.org/stable/2281644)

Clarke, D., Schythe, K.T. Implementing the panel event study. IZA Discussion Papers 13524, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), July (2020). https://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/dp13524.html

Acknowledgements

We thank participants of the International Institute of Public Finance (IIPF) in 2019 Glasgow, the American Society of Health Economists 8th Annual Conference (Ashecon) in Washington DC in 2019, and the Tobacco Online Policy Seminar in 2021 (TOPS), with special thanks to Michael Pesko for very helpful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dauchy, E., Shang, C. The pass-through of excise taxes to market prices of heated tobacco products (HTPs) and cigarettes: a cross-country analysis. Eur J Health Econ 24, 591–607 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01499-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01499-x