Abstract

Rectal prolapse is characterized by a full-thickness intussusception of the rectal wall and is associated with a spectrum of coexisting anatomic abnormalities. We developed the transabdominal levatorplasty technique for laparoscopic rectopexy, inspired by Altemeier’s procedure. In this method, following posterior mesorectum dissection, we expose the levator ani muscle just behind the anorectal junction. Horizontal sutures, using nonabsorbable material, are applied to close levator diastasis associated with rectal prolapse. The aim of the transabdominal levatorplasty is to (i) reinforce the pelvic floor, (ii) narrow the anorectal hiatus, and (iii) reconstruct the anorectal angle. We report a novel transabdominal levatorplasty technique during laparoscopic rectopexy for rectal prolapse. The laparoscopic mesh rectopexy with levatorplasty technique was performed in eight cases: six underwent unilateral Orr–Loygue procedure, one modified Wells procedure, and one unilateral Orr–Loygue procedure combined with sacrocolpopexy for uterine prolapse. The median follow-up period was 178 (33–368) days, with no observed recurrences. Six out of seven patients with fecal incontinence experienced symptomatic improvement. Although the sample size is small and the follow-up period is short, this technique has the potential to reduce the recurrence rate and improve functional outcomes, as with levatorplasty of Altemeier’s procedure. We believe that this technique may have the potential to become an option for rectal prolapse surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rectal prolapse is characterized by a full-thickness intussusception of the rectal wall and is associated with a spectrum of coexisting anatomic abnormalities.

The therapeutic goals of rectal prolapse surgery are to eliminate prolapse, correct the associated defecatory function, and prevent new bowel dysfunction [1]. Various surgical techniques, each with its own strengths and weaknesses, have been developed to achieve these goals. Generally, a perineal approach, such as Altemeier’s and Delorme procedures, is preferred for elderly patients with severe comorbidities. Perineal operations can be performed without general anesthesia, ensuring safety with low complications. However, perineal operation has high recurrence rates. In Altemeier’s procedure, adding levatorplasty to address levator diastasis can reduce recurrence rates and improve fecal continence [2,3,4,5]. Conversely, the transabdominal approach, such as the rectopexy with mesh fixation or suturing, is typically applied to younger and healthier patients. Although the recurrence rate of the transabdominal approach is lower than that of the perineal approach, it still ranges from 3% to 16% [6, 7]. The addition of sigmoidectomy can further reduce the recurrence rate and improve functional outcomes, albeit with an increase in morbidity.

We developed the transabdominal levatorplasty technique for laparoscopic rectopexy, inspired by Altemeier’s procedure. In this method, following posterior mesorectum dissection, we expose the levator ani muscle just behind the anorectal junction. Horizontal sutures, using nonabsorbable material, are applied to close levator diastasis associated with rectal prolapse. The aim of the transabdominal levatorplasty is to (i) reinforce the pelvic floor, (ii) narrow the anorectal hiatus, and (iii) reconstruct the anorectal angle. We report a novel transabdominal levatorplasty technique during laparoscopic rectopexy for rectal prolapse.

The video shows the laparoscopic mesh rectopexy using a unilateral Orr–Loygue procedure [8, 9] with levatorplasty technique for an 86-year-old woman with full-thickness rectal prolapse.

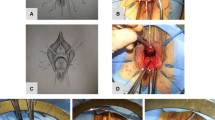

The peritoneum was divided from the right to the ventral side of the rectum. The posterior dissection of the mesorectum was performed until exposing the levator ani muscle surface. The fascia of the levator ani muscle was preserved, and the tip of the coccyx was identified by touching the tissue hardness with laparoscopic forceps. The dissection was carried out until the upper edge of the anal canal was reached, where there is tight connective tissue between the rectal longitudinal muscle and levator ani muscles.

The intersphincteric space was not opened to preserve the tight fixation between the anorectum and levator ani muscle. The right-side dissection was minimized to reduce damage to the rectal branch from the autonomic nerve. The anterior wall of the lower rectum was separated from the vaginal wall. The levator ani muscle just behind the anorectal junction was horizontally sutured using nonabsorbable sutures [V-Loc™ polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) wound closure device (3–0; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or PROLENEⓇ (3–0; ETHICON, Inc., Raritan, NJ, USA)], adjusting the tightness to allow the insertion of two fingers into the anal canal during digital rectal examination. The trimmed soft polypropylene mesh was then secured to the rectal wall and sacrum, and the peritoneum was completely closed.

The operative time was 142 min, with minimal blood loss. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged on day 7 post-surgery. At 3 months post-surgery, the Wexner score decreased from 16 to 4 points, showcasing dramatic improvement in fecal incontinence. The anorectal angle of magnetic resonance imaging was improved from 144 to 118 degrees, and the pelvic floor was lifted to the cranial side.

The laparoscopic mesh rectopexy with levatorplasty technique was performed in eight cases: six underwent unilateral Orr–Loygue procedure, one modified Wells procedure, and one unilateral Orr–Loygue procedure combined with sacrocolpopexy for uterine prolapse. The median age was 79 (72–90) years. The operative time was 175 (142–245) min, with minimal blood loss (0–4 mL). One case experienced urinary dysfunction (Clavien–Dindo grade II), but others were discharged without complications. The median follow-up period was 178 (33–368) days, with no observed recurrences. Six out of seven patients with fecal incontinence experienced symptomatic improvement, as evidenced by a decrease in the Wexner score by a median of 4 (0–12) points and an improvement in the anorectal angle by a median of 17 (3–33) degrees at 3 months post-surgery.

In perineal rectosigmoidectomy, levatorplasty contributes to a lower recurrence rate and improved postoperative fecal incontinence [2,3,4,5]. By suturing the diastasis of the levator ani, the pelvic floor is reinforced and the anorectal hiatus is narrowed. A study using anorectal manometry reported that the resting pressure was improved in Altemeier’s procedure with levatorplasty [5]. Although the transabdominal rectopexy can lift and fix the rectum, it cannot close the diastasis of the levator ani. Therefore, fecal incontinence in some patients was not improved even after transabdominal rectopexy, which may suggest that the rectopexy alone is insufficient. In this report, transabdominal levatorplasty proved to be simple and safe even for elderly patients. Moreover, this technique can be applied to other transabdominal rectopexy, such as Orr–Loygue procedure, modified Wells procedure, and sacrocolpopexy. We believe that this technique is an optional procedure with transabdominal rectopexy to reduce the recurrence rate and improve functional outcomes.

However, this surgery may exacerbate constipation by damaging the rectal branch of the autonomic nerve and constricting the anus. The lateral dissection is minimized, and the horizontal suture of the levator ani muscle adjusts to allow the insertion of two fingers into the anal canal during digital rectal examination. In levatorplasty with Altemeier’s procedure, a few sutures could not cause anal stenosis [3]. The sigmoidectomy or ventral rectopexy may be a better option for patients with severe constipation.

This report has several limitations. The small sample size, absence of comparison, and insufficient observation period make it insufficient to demonstrate the efficacy of transabdominal levatorplasy. Although this report is still in pilot study phase, this technique has the potential to reduce the recurrence rate and improve functional outcomes, as with the levatorplasty of Altemeier’s procedure. Further studies with larger sample sizes and multicenter studies, comparisons with procedures without levatorplasty, and long-term follow-up are necessary to validate the preliminary findings.

We believe that this technique may have the potential to be an option for rectal prolapse surgery.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at Japanese Red Cross Osaka Hospital. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author A.N. on request.

References

Bordeianou L, Paquette I, Johnson E, Holubar SD, Gaertner W, Feingold DL, Steele SR (2017) Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum 60:1121–1131. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000889. ([PubMed: 28991074])

Chun SW, Pikarsky AJ, You SY, Gervaz P, Efron J, Weiss E, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD (2004) Perineal rectosigmoidectomy for rectal prolapse: role of levatorplasty. Tech Coloproctol 8:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-004-0042-z. ([PubMed: 15057581])

Altemeier WA, Giuseffi J, Hoxworth P (1952) Treatment of extensive prolapse of the rectum in aged or debilitated patients. AMA Arch Surg 65:72–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1952.01260020084007. ([PubMed: 14932600])

Prasad ML, Pearl RK, Abcarian H, Orsay CP, Nelson RL (1986) Perineal proctectomy, posterior rectopexy, and postanal levator repair for the treatment of rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum 29:547–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02554250. ([PubMed: 3743295])

Köhler A, Athanasiadis S (2001) The value of posterior levator repair in the treatment of anorectal incontinence due to rectal prolapse—a clinical and manometric study. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 386:188–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004230100223. ([PubMed: 11382320])

D’Hoore A, Penninckx F (2006) Laparoscopic ventral recto (colpo) pexy for rectal prolapse: surgical technique and outcome for 109 patients. Surg Endosc 20:1919–1923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-005-0485-y. ([PubMed: 17031741])

Ng YY, Tan EJKW, Fu CWP (2022) Trends in the surgical management of rectal prolapse: an Asian experience. Asian J Endoscop Surg 15:110–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/ases.12978. ([PubMed: 34448361])

Meyer J, Liot E, Delaune V, Balaphas A, Roche B, Meurette G, Ris F (2023) Robotic mesh rectopexy for rectal prolapse: the Geneva technique—a video vignette. Colorectal Dis 25:2469–2471. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.16799. ([PubMed: 37926804])

Loygue J, Nordlinger B, Cunci O, Malafosse M, Huguet C, Parc R (1984) Rectopexy to the promontory for the treatment of rectal prolapse. Report of 257 cases. Dis Colon Rectum 27:356–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02552998. ([PubMed: 6376001])

Funding

There is nothing to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data creation and collection: K.K., A.N., T.O., S.I., K.N., R.K. Writing of the manuscript text: K.K., A.N., T.O. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Japanese Red Cross Osaka Hospital (Approval No. J-0556).

Informed consent

The patients included in this study formally and individually consented to the procedure.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (MP4 1380156 KB)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamihata, K., Nomura, A., Okada, T. et al. Transabdominal levatorplasty technique in laparoscopic mesh rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol 28, 101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-024-02975-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-024-02975-7