Abstract

Purpose

Initial reports of transanal ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (taIPAA) suggest safety and feasibility compared with transabdominal IPAA. The purpose of this study was to evaluate differences in technique and results of taIPAA in three centers performing taIPAA across two continents.

Methods

Prospective IPAA registries from three institutions in the US and Europe were queried for patients undergoing taIPAA. Demographic, preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data were compiled into a single database and evaluated.

Results

Sixty-two patients (median age 38 years; range 16–68 years, 43 (69%) male) underwent taIPAA in the three centers (USA 24, UK 23, Italy 15). Most patients had had a subtotal colectomy before taIPAA [n = 55 (89%)]. Median surgical time was 266 min (range 180–576 min) and blood loss 100 ml (range 10–500 ml). Technical variations across the three institutions included proctectomy plane of dissection (intramesorectal or total mesorectal excision plane), specimen extraction site (future ileostomy site vs. anus), ileo-anal anastomosis technique (stapled vs. hand sewn) and use of fluorescence angiography. Despite technical differences, anastomotic leak rates (5/62; 8%) and overall complications (18/62; 29%) were acceptable across the three centers.

Conclusions

This is the first collaborative report showing safety and feasibility of taIPAA. Despite technical variations, outcomes are similar across centers. A large multi-institutional, international IPAA collaborative is needed to compare technical factors and outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) is the standard operation for ulcerative colitis (UC) and inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBDu). Traditionally performed through an open incision, minimally invasive IPAA has become increasingly more common [1, 2] with short-term advantages such as reduced pain, shorter hospital stay and faster gastrointestinal recovery [1, 3, 4]. In addition long-term benefits of laparoscopic IPAA include fewer adhesions [5], improved cosmesis [6], shorter operative time and faster recovery in subsequent ileostomy closure [7], and improved fertility [8] over open IPAA. Despite the growing trend toward minimally invasive IPAA [9,10,11] and reports of single- or reduced-port IPAA [9, 10], this complex abdomino-pelvic operation is still most commonly performed through a hybrid approach with laparoscopic colectomy followed by open proctectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision [3, 11].

Transanal proctectomy is a new approach first described in rectal cancer [12] with potential oncologic advantages over transabdominal proctectomy [13,14,15,16,17]. Transanal proctectomy has also been used in IPAA surgery [9, 18] with early results of transanal IPAA (taIPAA) suggesting feasibility and safety [19] with potentially lower morbidity compared with transabdominal minimally invasive IPAA in European referral centers [20]. TaIPAA has been adopted by several high-volume inflammatory bowel disease centers across the world. The technique is in evolution and “best” approach is yet to be determined. The purpose of this study was to compare technical variability and feasibility of taIPAA across three centers in the United States and Europe.

Materials and methods

Prospectively maintained IPAA registries at three institutions (1: Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, USA; 2: St. Mark’s Hospital, London, UK; 3: Humanitas Hospital, Milan, Italy) were queried for patients undergoing Ta-IPAA for UC or IBDu between December 2015 and October 2017, and data were compiled and analyzed.

Surgical technique

While the current standard at all three institutions is a two-team approach, a few initial cases were performed by a single team. Across the three institutions, the following portions of taIPAA are performed similarly with laparoscopic assistance. With the patient in low lithotomy position, an abdominal colectomy is first performed either by conventional multiport laparoscopy or single-port access with a GelPoint® Mini (Applied Medical Inc., Rancho Santa Margarita, California, USA) through the future ileostomy site in the right lower quadrant, sometimes with one or two additional 5- or 10-mm assistant trocars placed in the suprapubic or left lower quadrant positions to assist with triangulation and exposure. The abdominal colectomy is performed in a standard fashion with close to bowel mesenteric dissection and preservation of the ileocolic pedicle. Assessment of small bowel mesenteric tension for pouch reach is assessed and if there is an adequate reach, the terminal ileal mesentery is dissected off the duodenal sweep. The terminal ileum is typically transected extracorporeally through the ileostomy site (GIA 80, Covidien, Dublin Ireland or TLC 75, Ethicon Inc, Sommerville, NJ, USA). The pelvic dissection is then commenced. The superior hemorrhoidal artery is divided with the Ligasure™ (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) or Harmonic ACE® (Ethicon Inc., Sommerville, NJ, USA) and proctectomy begun by both the abdominal and transanal teams. The extent of abdominal proctectomy performed is dependent on patient factors and difficulty of dissection. The abdominal team can also create the ileal pouch through the future ileostomy site while the transanal team begins its dissection.

The transanal phase of the dissection is commenced by placement of a Lone-Star® retractor (CooperSurgical Inc., Trumbull, CT, USA) followed by insertion of the GelPoint® Path (Applied Medical Inc., Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA). Next, a purse-string suture is placed above the anorectal ring approximately 3–4 cm from the dentate line and Airseal® (Conmed Inc, Utica, NY, USA) insufflation started. Full-thickness proctectomy is created just distal to the purse-string suture and the rectal dissection carried toward the abdominal operator. The dissection may be performed in the total mesorectal excision (TME) plane or within the intramesorectal dissection plane. Anterior dissection is performed close to the rectum, and the anterior and posterior planes connected laterally close to the mesorectum to avoid injury to the nervi erigentes. At the point of rendezvous, the abdominal and transanal teams work together to dismount the rectum after which the specimen is extracted transanally or through the future ileostomy site. The pouch is then delivered to the pelvis and rectal cuff length determined depending on pouch tension and patient factors. In cases where reach is plentiful, a partial or complete mucosectomy may be performed. A double purse-string stapled or hand-sewn anastomosis is then performed by the transanal team while the abdominal operator performs the diverting ileostomy.

In cases where a subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy has previously been performed, the surgery is started by takedown of the ileostomy followed by placement of the GelPoint® Mini through the ileostomy site. Single-port surgery is performed by the abdominal team to assess pouch reach and mobilize the terminal ileal attachments off the retroperitoneum and duodenal sweep. Once pouch reach has been determined, the transanal team begins the transanal proctectomy and remainder of the procedure continues as above.

Assessment of perioperative factors

Preoperative demographic and clinical factors evaluated included patient age and gender, the presence of comorbid disease classified according to the Charlson Age Comorbidity Index [21], use of corticosteroids at the time of surgery, prior or current use of a biologic and duration since last dose, preoperative body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and preoperative disease classification (UC or IBDu). UC was defined clinically when patients had no perianal disease, and endoscopic and histologic features included continuous inflammation extending proximally from the dentate line. Patients were classified as having IBDu or postoperative indeterminate colitis (IC) when they had clinical features of UC with some features suggestive but not diagnostic of Crohn’s disease, according to the Montreal classification [22].

Operative characteristics measured included number of stages (two-stage or three-stage IPAA), with two-stage IPAA defined as initial IPAA with diverting ileostomy followed by ileostomy closure and three-stage IPAA being initial subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy, followed by completion proctectomy with IPAA and diverting ileostomy, and finally ileostomy closure. In cases of staged IPAA where subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy was performed first, the approach for subtotal colectomy (total laparoscopic, robotic, hand assist, or open) was recorded. Other data collected included whether diverting ileostomy was performed at the time of IPAA, plane of proctectomy dissection (TME plane vs. intramesorectal), site of specimen extraction (anus, ileostomy site, or other), method of anastomosis (double purse-string stapled, hand sewn to rectal cuff, or hand sewn to dentate line), and use of fluorescence angiography to determine pouch perfusion prior to anastomosis. Complications occurring in the 30-day postoperative period were recorded and classified according to the Clavien–Dindo classification [23]. Pelvic abscess was defined radiographically or clinically at reoperation. Anastomotic leaks were defined radiographically either by computed tomography (CT) scan or contrast-enema study showing contrast extravasation or sinus-tract or clinically at the time of reoperation or rectal exam under anesthesia identifying an anastomotic defect. Pelvic abscess and leak were compiled together as a single entity in this early postoperative period.

Statistical analysis

A single de-identified Microsoft® Excel (Redmond, WA, USA) file was created including all taIPAA patients across the three centers and was analyzed. Descriptive statistics was performed using online statistics calculator (http://www.graphpad.com) with continuous variables reported as median (range) and categorical variables as n (%). Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables compared using Fisher’s exact test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

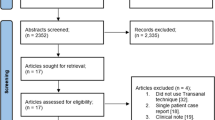

A total of 62 patients, mostly male (n = 43; 69%), with UC (n = 60; 97%) or IBDu (n = 2; 3%) had taIPAA during the study period across the US (n = 24), UK (n = 23), and Italy (n = 15). Patients were thin (median BMI 21.8 kg/m2; range 14.0–27.8 kg/m2), healthy (95% with ASA class 1 or 2) and young (median age 38 years; range 16–68 years) (Table 1). Preoperative medication use including corticosteroids (n = 35; 56%) and biologics (n = 39; 63%) were common. Most procedures were staged with 55 (89%) patients previously having had a subtotal colectomy before taIPAA, and this was consistent across the three institutions (Fig. 1). Median surgical time was 266 min (range 180–576 min) and median blood loss was 100 ml (range 10–500 ml). Proctectomy was performed in the TME plane in the US and UK while the Italian center preferred an intramesorectal dissection in 87% of their patients (Fig. 1). In the UK and Italy, the ileostomy site was chosen for the majority of specimen extractions, while the US center exclusively performed transanal specimen extraction (Fig. 1). All anastomoses were performed in a stapled double purse-string fashion in the UK and Italy. In the US the anastomosis was tailored to patient factors. When there was rectal dysplasia or when pouch reach to the dentate line appeared to have minimal tension, a rectal mucosectomy was performed with anastomosis to the dentate line (n = 8). When tension prohibited pouch reach to the dentate line, a stapled double purse-string anastomosis (n = 12) or hand-sewn anastomosis directly to the rectal cuff (n = 4) was performed. Median hospital stay was 6 days (2–24). Only the Italian center used fluorescence angiography to confirm pouch perfusion in 10 out of 15 (67%) patients, with one pouch revised due to poor perfusion resulting in an uncomplicated postoperative course. Almost all patients (98%) had a diverting ileostomy. Median postoperative hospital stay was 6 (2–24) days and complications occurred in 18 (29%) patients (Table 2).

Anastomotic leak or pelvic abscess occurred in five (8%) patients. No preoperative or technical factors related to taIPAA predicted anastomotic leak (p = NS for all) (Fig. 2). While none of the patients having intramesorectal dissection (0/13) developed a serious complication (CD grade ≥ 3) or anastomotic leak, this was not significantly different than the rate of serious complications (4/49; 8%; p = 0.6) or leak (5/49; 10%; p = 0.6) in the remainder of the study cohort. Anastomotic leaks were also unaffected by the type of anastomosis whether hand sewn to the dentate line (1/8; 13%), hand sewn to the rectal cuff (0/4) or stapled (4/50; 8%) (p = 0.7). There was also no difference in the incidence of anastomotic leaks between transanal (3/26; 12%) and stoma-site specimen extraction (2/36; 6%) (p = 0.6). While none of the patients having fluorescence angiography developed an anastomotic leak, there was no statistically significant difference in anastomotic leak rates between patients having fluorescence angiography and the remainder of the study cohort (0 vs. 9.6%; p = 1). No patients had urethral injuries.

Discussion

TaIPAA is increasingly being performed across the world. Growing interest in this technique is driven by its many potential advantages. Access to the distal rectum especially in a narrow pelvis is one of the potential benefits of taIPAA and similar to taTME for rectal cancer [15, 17]. In addition, the ability to perform a single-stapled anastomosis and elimination of multiple-staple firings carry the potential for reduced anastomotic leaks. Third, the ability to tailor the distal rectal transection and rectal cuff length to patient factors and pouch reach may improve functional outcomes [18]. Finally, by minimizing incisions through transanal or trans-stomal extraction, postoperative pain, wound infections, and recovery may be improved [20]. The largest published experience with taIPAA has demonstrated safety and feasibility of taIPAA vs. transabdominal minimally invasive IPAA in European referral centers [20]. In this study, 97 patients having taIPAA had 0.52 times lower postoperative morbidity (95% CI (0.29; 0.92); p = 0.03) than 119 patients having transabdominal IPAA. However, the taIPAA technique is still in evolution, and as various centers across the world begin to utilize this approach for IPAA surgery, techniques will continue to develop to improve patient outcomes.

This is the first bicontinental study of taIPAA, and first to include a US center. In this study, we have shown that while technical aspects of taIPAA may vary across centers, the transanal approach is feasible and safe with acceptable outcomes. Commonality across the three centers includes a high rate of three-stage IPAA and preference for a two-team approach with abdominal dissection performed through the future ileostomy site. However, the three centers varied their approach in several important ways. In the US and UK, proctectomy was performed in the TME dissection plane while the Italian approach was an intramesorectal dissection. Intramesorectal or close rectal dissection (CRD) for transabdominal IPAA has previously been studied in a randomized trial vs. dissection in the TME plane with results suggesting longer operative time but reduced serious complications with CRD vs. TME plane dissection (2/28 vs. 10/31; p = 0.02) [24]. In taIPAA, intramesorectal dissection may be even more challenging due to bleeding obscuring a tight surgical field resulting in a preference for TME dissection plane by two out of three centers. In the current study, while none of the 13 patients having intramesorectal dissection developed a serious complication (CD grade ≥ 3), this was not significantly different than the rate of serious complications or anastomotic leak in patients who have a dissection in the TME plane. Higher patient numbers may prove this observation to be statistically and hence clinically significant.

The site of specimen extraction was another area of difference across centers. Both approaches appear acceptable with respect to short-term results. However, long-term implications of each technique (potential hernias due to an enlarged stoma site to accommodate a bulky specimen [25] vs. impaired anal continence due to transanal extraction [26]) were not assessed here.

Another important distinction between the US and European centers was the anastomotic technique. While in both European centers the anastomosis was created by a stapled, double-purse-string technique, in the US the anastomosis was tailored to patient factors. Most anastomoses in the US were still performed in a stapled double-purse-string fashion. However, when the pouch easily reached the dentate line, especially in the setting of rectal dysplasia or severe rectal inflammation, a mucosectomy was performed with anastomosis to the dentate line. In a small subset of patients, the anastomosis was hand sewn directly to the rectal cuff, or the rectal cuff was tailored to pouch reach through a partial mucosectomy with anastomosis to the remaining rectal cuff. The ability to tailor the rectal cuff and level of anastomosis to patient factors and pouch reach is one of the unique advantages of taIPAA. However, in this small study, the type of anastomosis created did not affect anastomotic leak or complication rates.

Another variation was the use of fluorescence angiography by the Italian center. The potential advantage of fluorescence angiography has recently emerged in colorectal surgery. Despite the absence of randomized trials, this technology is gaining increasing popularity due to its potential to detect insufficiently perfused bowel and change operative management, especially in rectal surgery [27, 28]. Use of fluorescence angiography to evaluate pouch perfusion has also been described in taIPAA surgery [29]. In the current series, the use of fluorescence angiography did not appear to impact surgical complications or anastomotic leak rate.

The most important limitations of our study are small sample size and the lack of a comparison group consisting of transabdominal taIPAA. We chose not to include a comparison group as this would further confound the results of this small study highlighting technical variations in taIPAA across continents. Further, meaningful analysis of a heterogeneous cohort of transabdominal IPAA patients also with variations in approach (open vs. laparoscopic; double stapled vs. mucosectomy) would be statistically futile against this small taIPAA cohort. Our small sample size with technical variability between centers also prohibits meaningful determination of factors influencing complications and anastomotic leak rates in this taIPAA cohort. This study is limited to short-term follow-up and long-term results such as quality of life as well as pouch, sexual, and urinary functions remain unknown. The study cohort remains limited to a selected cohort of young, generally healthy, and thin IBD patients, and may not be generalizable to a broader patient cohort. In addition, all three centers remain in their learning curve with studies of transanal TME suggesting that proficiency is reached at 40–50 cases [30, 31]. The learning curve may have contributed to outcome measures including operative time and surgical complications with each center clearly still within the learning curve with an experience of 15–24 cases at each site. While postoperative hospital length of stay varied greatly with a range of 2–24 postoperative days across centers, this variability may be a reflection of different recovery pathways across continents.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a transanal IPAA may be performed safely in experienced hands and that technical variations such as proctectomy dissection plane, site of specimen extraction, and method of anastomosis do not greatly impact short-term patient outcomes. Large-scale, multi-institutional and multi-national collaboration is needed to evaluate the influence of technical factors on patient outcomes in this evolving approach to a complex abdominopelvic operation with many potential variations in technique.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baek SJ, Dozois EJ, Mathis KL, Lightner AL, Boostrom SY, Cima RR, Pemberton JH, Larson DW (2016) Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes in 588 patients undergoing minimally invasive ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a single-institution experience. Tech Coloproctol 20:369–374

Rencuzogullari A, Gorgun E, Costedio M, Aytac E, Kessler H, Abbas MA, Remzi FH (2016) Case-matched comparison of robotic versus laparoscopic proctectomy for inflammatory bowel disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 26:e37–e40

Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, Davies M, Piotrowicz K, Barnes SA, Wolff B, Pemberton J (2006) Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch-anal anastomosis: a single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg 243:667–670 (discussion 70–72)

White I, Jenkins JT, Coomber R, Clark SK, Phillips RK, Kennedy RH (2014) Outcomes of laparoscopic and open restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 101:1160–1165

Hull TL, Joyce MR, Geisler DP, Coffey JC (2012) Adhesions after laparoscopic and open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis surgery for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 99:270–275

Polle SW, Dunker MS, Slors JF, Sprangers MA, Cuesta MA, Gouma DJ, Bemelman WA (2007) Body image, cosmesis, quality of life, and functional outcome of hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy: long-term results of a randomized trial. Surg Endosc 21:1301–1307

Hiranyakas A, Rather A, da Silva G, Weiss EG, Wexner SD (2013) Loop ileostomy closure after laparoscopic versus open surgery: is there a difference? Surg Endosc 27:90–94

Beyer-Berjot L, Maggiori L, Birnbaum D, Lefevre JH, Berdah S, Panis Y (2013) A total laparoscopic approach reduces the infertility rate after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a 2-center study. Ann Surg 258:275–282

Benlice C, Gorgun E (2016) Single-port laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with ileal-pouch anal anastomosis using a left lower quadrant ileostomy site—a video vignette. Colorectal Dis 18:818–819

Gash KJ, Goede AC, Kaldowski B, Vestweber B, Dixon AR (2011) Single incision laparoscopic (SILS) restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Surg Endosc 25:3877–3880

Remzi FH, Lavryk OA, Ashburn JH, Hull TL, Lavery IC, Dietz DW, Kessler H, Church JM (2017) Restorative proctocolectomy: an example of how surgery evolves in response to paradigm shifts in care. Colorectal Dis 19:1003–1012

Sylla P, Rattner DW, Delgado S, Lacy AM (2014) NOTES transanal rectal cancer resection using transanal endoscopic microsurgery and laparoscopic assistance. Surg Endosc 24:1205–1210

Atallah S (2014) Transanal minimally invasive surgery for total mesorectal excision. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 23:10–16

Chouillard E, Regnier A, Vitte RL, Bonnet BV, Greco V, Chahine E, Daher R, Biagini J (2016) Transanal NOTES total mesorectal excision (TME) in patients with rectal cancer: Is anatomy better preserved? Tech Coloproctol 20:537–544

de Lacy FB, van Laarhoven J, Pena R, Arroyave MC, Bravo R, Cuatrecasas M, Lacy AM (2018) Transanal total mesorectal excision: pathological results of 186 patients with mid and low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc 32:2442–2447

Persiani R, Biondi A, Pennestri F, Fico V, De Simone V, Tirelli F, Santullo F, D’Ugo D (2018) Transanal total mesorectal excision vs laparoscopic total mesorectal excision in the treatment of low and middle rectal cancer: a propensity score matching analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 61:809–816

Penna M, Hompes R, Arnold S, Wynn G, Austin R, Warusavitarne J, Moran B, Hanna GB, Mortensen NJ, Tekkis PP (2017) Transanal total mesorectal excision: international registry results of the first 720 cases. Ann Surg 266:111–117

de Buck van Overstraeten A, Wolthuis AM, D’Hoore A (2016) Transanal completion proctectomy after total colectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: a modified single stapled technique. Colorectal Dis 18:141–144

Leo CA, Samaranayake S, Perry-Woodford ZL, Vitone L, Faiz O, Hodgkinson JD, Shaikh I, Warusavitarne J (2016) Initial experience of restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis by transanal total mesorectal rectal excision and single-incision abdominal laparoscopic surgery. Colorectal Dis 18:1162–1166

de Buck van Overstraeten A, Mark-Christensen A, Wasmann KA, Bastiaenen VP, Buskens CJ, Wolthuis AM, Vanbrabant K, D’Hoore A, Bemelman WA, Tottrup A, Tanis PJ (2017) Te Ann Surg 266:878–883

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J (1994) Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 47:1245–1251

Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV Jr, Pena AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF (2005) Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 19(Suppl A):5–36

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Bartels SA, Gardenbroek TJ, Aarts M, Ponsioen CY, Tanis PJ, Buskens CJ, Bemelman WA (2015) Short-term morbidity and quality of life from a randomized clinical trial of close rectal dissection and total mesorectal excision in ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg 102:281–287

Li W, Benlice C, Stocchi L, Kessler H, Gorgun E, Costedio M (2017) Does stoma site specimen extraction increase postoperative ileostomy complication rates? Surg Endosc 31:3552–3558

Denost Q, Adam JP, Pontallier A, Celerier B, Laurent C, Rullier E (2015) Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision with coloanal anastomosis for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 261:138–143

Hellan M, Spinoglio G, Pigazzi A, Lagares-Garcia JA (2014) The influence of fluorescence imaging on the location of bowel transection during robotic left-sided colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc 28:1695–1702

James DR, Ris F, Yeung TM, Kraus R, Buchs NC, Mortensen NJ, Hompes RJ (2015) Fluorescence angiography in laparoscopic low rectal and anorectal anastomoses with pinpoint perfusion imaging–a critical appraisal with specific focus on leak risk reduction. Colorectal Dis 17(Suppl 3):16–21

Spinelli A, Cantore F, Kotze PG, David G, Sacchi M, Carvello M (2017) Fluorescence angiography during transanal trans-stomal proctectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13992

Lee L, Kelly J, Nassif GJ, deBeche-Adams TC, Albert MR, Monson JRT (2018) Defining the learning curve for transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6360-4

Koedam TWA, Veltcamp Helbach M, van de Ven PM, Kruyt PM, van Heek NT, Bonjer HJ, Tuynman JB, Sietses C (2018) Transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: evaluation of the learning curve. Tech Coloproctol 22:279–287

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

PF—teaching honorarium from Applied Medical, Inc. AS—teaching honorarium from Applied Medical, Inc. KZ—financial assistance for course attendance from Applied Medical, Inc.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from patients across the sites.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zaghiyan, K., Warusavitarne, J., Spinelli, A. et al. Technical variations and feasibility of transanal ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease unclassified across continents. Tech Coloproctol 22, 867–873 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-018-1889-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-018-1889-8