Abstract

Background

Anoperineal lesion (APL) occurrence is a significant event in the evolution of Crohn’s disease (CD). Management should involve a multidisciplinary approach combining the knowledge of the gastroenterologist, the colorectal surgeon and the radiologist who have appropriate experience in this area. Given the low level of evidence of available medical and surgical strategies, the aim of this work was to establish a French expert consensus on management of anal Crohn’s disease. These recommendations were led under the aegis of the Société Nationale Française de Colo-Proctologie (SNFCP). They report a consensus on the management of perianal Crohn’s disease lesions, including fistulas, ulceration and anorectal stenosis and propose an appropriate treatment strategy, as well as sphincter-preserving and multidisciplinary management.

Methodology

A panel of French gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons with expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases reviewed the literature in order to provide practical management pathways for perianal CD. Analysis of the literature was made according to the recommendations of the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) to establish a level of proof for each publication and then to propose a rank of recommendation. When lack of factual data precluded ranking according to the HAS, proposals based on expert opinion were written. Therefore, once all the authors agreed on a consensual statement, it was then submitted to all the members of the SNFCP. As initial literature review stopped in December 2014, more recent European or international guidelines have been published since and were included in the analysis.

Results

MRI is recommended for complex secondary lesions, particularly after failure of previous medical and/or surgical treatments. For severe anal ulceration in Crohn’s disease, maximal medical treatment with anti-TNF agent is recommended. After prolonged drainage of simple anal fistula by a flexible elastic loop or loosely tied seton, and after obtaining luminal and perineal remission by immunosuppressive therapy and/or anti-TNF agents, the surgical treatment options to be discussed are simple seton removal or injection of the fistula tract with biological glue. After prolonged loose-seton drainage of the complex anal fistula in Crohn’s disease, and after obtaining luminal and perineal remission with anti-TNF ± immunosuppressive therapy, surgical treatment options are simple removal of seton and rectal advancement flap. Colostomy is indicated as a last option for severe APL, possibly associated with a proctectomy if there is refractory rectal involvement after failure of other medical and surgical treatments. The evaluation of anorectal stenosis of Crohn’s disease (ARSCD) requires a physical examination, sometimes under anesthesia, plus endoscopy with biopsies and MRI to describe the stenosis itself, to identify associated inflammatory, infectious or dysplastic lesions, and to search for injury or fibrosis of the sphincter. Therapeutic strategy for ARSCD requires medical–surgical cooperation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Anoperineal lesions (APL) are a significant event in the evolution of Crohn’s disease (CD). The management of these lesions is particularly difficult due to the tendency to tissue destruction and recurrence, and also to the serious impact on continence, sexuality and quality of life. The presence of APL when CD is diagnosed is a poor prognostic factor, especially in young adults [1, 2]. In a third to a half of cases, APL reveals CD [3]. Among the different types of APL, abscess is the most frequent; the cumulative incidence of anoperineal fistula at 10 years is estimated to be between 21 and 33% [3, 4]. Given the low level of evidence for the medical and surgical treatment strategies available, we carried out the present review with the aim of establishing French expert consensus guidelines for the management of anal Crohn’s disease. We established national recommendations based on literature analysis and on our experience, under the aegis of the Société Nationale Française de Colo-Proctologie (SNFCP). These recommendations represent a consensus regarding the management of perianal lesions in CD, including fistulas, ulcers and anorectal stenosis and cover appropriate treatment strategy, as well as sphincter-preserving and multidisciplinary management.

Materials and methods

A panel of French gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons with expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases reviewed the literature in order to provide practical management pathways for perianal CD. The authors reviewed all the aspects of perianal CD, from diagnosis to treatment. Statements were associated with Grade of Recommendation, and two management algorithms were designed for anorectal ulcer and anorectal stricture in CD.

All the authors searched the PubMed and Cochrane databases for articles published since 1970. An analysis of the literature was made according to the recommendations of the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) allowing us to establish a level of proof for each publication and then to propose a rank of recommendation. When lack of factual data precluded establishing a rank of recommendation according to the HAS, proposals based on expert opinion were written. Therefore, when all the authors agreed on a consensus statement, it was then submitted to all the members of the SNFCP. Grades from 1 to 9 were attributed according to the RAND/UCLA method, and analysis of the results and eventual rewriting of the statement were done by the coordinator of this work. These statements were named “professional agreement” or “AP”. As the initial literature review stopped in December 2014, more recent European or international guidelines published since then have been included for analysis [5,6,7].

Classification for APL in CD

Multiple classifications of APL associated with CD have been proposed, each based on different features: pathogenesis, anatomy, symptoms, quality of life or prognosis. They make possible assessment of the initial severity of anoperineal involvement, and the response to treatment, and help to guide therapy. In clinical practice, most experts use the Cardiff UFS classification [8] to describe APL, or the American Gastroenterological Association classification [9] for the particular case of fistulas. The Perianal Disease Activity Index (PDAI) score is the most frequently used to assess the clinical severity of perianal involvement with CD [10]. New scores evaluating digestive performance or the handicaps due to the disease make possible a different assessment of CD. Their relevance in the global care of the disease is still under evaluation.

The majority of the experts use the classification UFS of Cardiff to describe anorectal CD | |

PDAI is advocated to evaluate the clinical severity of anal CD |

Imaging of APL in CD

Imaging studies of APL complement data obtained from clinical evaluation, physical examination and rectal endoscopy. The role of imaging for primary lesions such as ulcers and fissures has not been evaluated to date. For patients with abscesses and strictures, most authors recommend performing an imaging study, particularly for patients who fail to respond to medical or surgical treatment and for patients suffering from anal incontinence [11, 12]. This recommendation could be extended to all secondary lesions, even simple ones, because of the potential for progression, diagnostic difficulties and severity of functional outcomes [13,14,15]. Imaging studies help to assess the anatomic extent of suppurating lesions (fistulous tracts and diverticula), the anatomy of the sphincter and the appearance of the rectal wall. The preferred imaging study is perineal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI in combination with examination under anesthesia (EUA) should achieve a 100% level of accuracy [3, 16, 17]. Results of MRI may change the fistulae surgical approach in 10–20% of cases by identifying extensions of sinus tracts not identified on EUA [11, 18,19,20,21,22]. MRI allows the surgeon to significantly reduce the recurrence rate after surgery and to predict its site in 52% of cases [22]. MRI can also differentiate between inflammatory and fibrotic fistulous tracts and assess the degree of rectal involvement; findings concord well with endoscopic results [23,24,25,26]. The Van Assche MRI score can help in the management of APL due to CD, but its reproducibility and prognostic value have not yet been assessed [26]. Endoanal ultrasonography (EAUS) may be an alternative imaging study. Its diagnostic accuracy for CD-related APL is estimated to be 56–100%. Compared to MRI, EAUS offers poorer definition of secondary sinus tracts but better detection of the internal opening and better evaluation of the sphincter. It does not evaluate the inflammatory character of lesions [27,28,29,30].

Key points on imaging of APL in CD

Imaging is recommended for complex secondary lesions, particularly after failure of previous medical and/or surgical treatments (grade B); | |

Imaging may also be recommended for simple secondary lesions, because of prognostic and therapeutic implications (grade B); | |

For imaging of APL, first-line examination should be MRI (grade B); | |

Addition of EUA may improve the accuracy of MRI (grade B); | |

EAUS, possibly associated with injection of hydrogen peroxide, offers the advantage of 3-D assessment and may be equivalent to MRI (grade B); | |

Computed tomography and fistulogram have no place for this indication (grade B and C, respectively); | |

If MRI and EAUS are unavailable, examination under general anesthesia is required (grade C); | |

The prognostic value of imaging (including MRI) in the therapeutic evaluation and its impact on the management of patients has yet to be defined (grade B) |

Therapeutic management of APL in CD

There is no consensus today on the management of CD-related APL, particularly in the case of ulcers or primary lesions. For suppurative lesions, data from the current literature indicate a strategy, based primarily on initial surgical drainage followed by medical treatment of the disease (grade B). Oral antibiotics (quinolones and metronidazole) have demonstrated a transitory efficacy while awaiting a response to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) blockers. Moreover, while the use of infliximab for this indication is based on large randomized controlled studies [31, 32], the efficacy of other anti-TNF agents and conventional immunosuppressive agents (azathioprine, methotrexate, ciclosporine) is more difficult to interpret. Finally, the efficacy of other therapeutic agents (tacrolimus, thalidomide) has not been proven to date.

Treatment of anal ulcers in CD

Anal ulcers associated with CD (AUCD) are specific inflammatory lesions of CD. These primary lesions are classified according to the Cardiff UFS classification [8]. They can be painful when they are extensive or penetrating, resulting in abscesses or fistulas and ultimately, potentially in sphincter destruction or anal stenosis. However, the natural progression of these lesions is unknown. The cumulative probability of developing AUCD within 10 years of initial diagnosis of CD exceeds 25% [33]. AUCD are indicators of disease severity, and the frequency of their occurrence increases with more distal colonic intestinal involvement [34, 35]. Surgical treatments that could expose patients to poor healing, or increase the risk of suppuration or secondary incontinence, should be avoided [insufficient evidence (IE)]. There is no specific controlled study on medical treatment of AUCD. Recommendations are therefore based on data from open studies, retrospective studies, or subgroup analyses, validated by professional consensus. For severe AUCD, maximal medical treatment with an anti-TNF agent is recommended, because of the risk of destructive evolution (grade C). Infliximab is the medication of choice for AUCD for both induction and maintenance, preferably in combination with azathioprine [36,37,38,39] (grade C). The efficacy of adalimumab has not been specifically documented for AUC but, by extrapolation, it could be similar to that of infliximab [40, 41] (IE). For a solitary superficial AUCD of limited extent without associated proctitis, close monitoring is recommended, sometimes associated with azathioprine therapy (IE). However, the efficacy of azathioprine alone has not been proved in the treatment of AUCD, even though it might reduce the incidence of these lesions (IE) [36,37,38,39,40,41]. Surgical drainage is only recommended in case of anorectal suppuration, abscess or complex fistula complicating a deep ulceration. If medical treatment for highly symptomatic and disabling AUCD fails, proximal gastrointestinal stomal diversion ± proctectomy can be considered (IE). Because it entails a risk of anal incontinence, sphincterotomy should not be performed in the setting of proven anoperineal CD (IE).

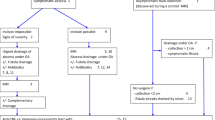

A decision-making algorithm to guide treatment is proposed in Fig. 1.

Treatment of anoperineal fistula in (AFCD)

Overall framework of therapeutic management

Perianal abscesses arise from either an infection of the pectineal glands of Hermann and Desfosses or from primary anorectal ulceration. They often develop complex and atypical fistulous tracts in CD. Most often, AFCD arise from AUCD and typically follow a chronic course of spontaneous relapse and recurrence [2,3,4, 42]. The extent of intraluminal disease should always be assessed before initiating treatment, but treatment of AFCD is essential regardless of the specific treatment option (IE). The American Gastroenterological Association classification differentiates simple anal fistulas (inter- or low transsphincteric tract with a single external opening, without abscess, anorectal stenosis or inflammation) from all other complex fistulas [9]. The complexity of these fistulous tracts requires accurate preoperative mapping by imaging, principally by MRI and/or EAUS (grade C) [9, 13, 14]. The goal of treatment is to cure the suppuration while limiting anoperineal sequelae and, especially, preserving continence. Treatment includes a surgical phase of abscess drainage and a medical phase, specific to CD, aimed at the underlying local and associated luminal inflammation. Drainage of abscesses and insertion of a seton through the fistulous tract are prerequisite for any management strategy, except in cases of dry and non-productive fistula without abscess (grade B). A seton or elastic loop should be inserted and tied without tension, to avoid pain and sphincter transsection. Initial medical treatment may include the temporary use of ciprofloxacin for treatment of inflammatory AFCD during the first weeks of induction biotherapy (grade B). TNF-α antagonists are the most effective medical treatments for AFC at this time (grade A). Today, there is insufficient data to recommend the use of certolizumab or vedolizumab. There is lack of evidence to recommend the use of tacrolimus, thalidomide or ciclosporine. Too short a duration of seton drainage may favor recurrence of abscess while prolonged drainage may interfere with healing of the fistula [43]. Drainage for at least 3 weeks, seems to promote healing, particularly for complex fistulas, but should not exceed 34 weeks [44]. This drainage does not eliminate the risk of recurrence [45]. Local clinical or imaging criteria have no demonstrated a prognostic role for the timing of seton removal. After seton removal, MRI evidence of a persistent residual fistula despite closure of the cutaneous opening is a risk factor for recurrence [46].

Simple AFCD

Short-term treatment with ciprofloxacin can be recommended for the treatment of inflammatory symptomatic AFCD during the first weeks of induction biotherapy (grade B).

For simple anal fistula, azathioprine is justified by its moderate effectiveness for closing fistulas and the reduced incidence of complex lesions requiring surgery (grade B). For simple AFCD, indications for infliximab and adalimumab therapy should be discussed based on the existence of perineal risk factors. Among surgical options, fistulotomy is contraindicated because of the risk of incontinence (IE), except for the rare cases of very superficial isolated fistulas in a patient with no perineal sequelae (IE). In patients with previously well-drained fistulas, without associated abscesses and whose disease is medically controlled conservative surgical techniques can be discussed (biological glue and plug) [47, 48], but only biological glue has demonstrated a significantly higher efficacy than simple seton removal [47] (grade A). The option of performing a rectal advancement flap should not be proposed for simple anal fistula because it is associated with a 10% risk of serious continence disorders [49]. Other surgical techniques such as ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) and other reconstruction techniques have not proven their effectiveness.

Key points in the treatment of simple AFCD

After prolonged drainage of simple anal fistula with a flexible elastic loop or loosely tied seton, and after obtaining luminal and perineal remission with immunosuppressive therapy and/or anti-TNF agents, the surgical treatment options to be discussed are simple seton removal or injection of the fistula tract with biological glue |

Complex AFCD

The management of complex AFCD is based on combined medical and surgical treatment (grade B). Ciprofloxacin can be recommended for early treatment of inflammatory symptomatic anal fistula during the first weeks of induction therapy with biologics (grade B). TNF antagonists are the most effective treatment for complex AFCD. Infliximab should be used, preferably in combination with immunosuppressive therapy (grade A). The efficacy of adalimumab for complex AFCD is based on non-dedicated clinical studies with lesser methodological reliability than studies of infliximab. However, the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) European consensus recommendations [50] put them on an equal footing. The efficacy of combination therapy with immunosuppressants is less clear for adalimumab than for infliximab [51]. The surgical option of fistulotomy is not recommended because of the risk of inducing incontinence (IE). In patients with previously well-drained fistulas, without associated abscesses whose disease is medically controlled conservative surgical techniques such as biological glue and plug have not demonstrated a significantly better efficacy than simple seton removal (grade A), but these studies concern patients who were not receiving anti-TNF therapy [47, 48]. The LIFT procedure should be evaluated as a possible alternative [52]. A low rectal advancement flap may be an option in very strictly selected patients with no evidence of proctitis or anal stenosis [53]. Flap is the surgical technique which has been most thoroughly evaluated to date in the management of anal fistulas in CD. Recently injection of stem cells into the tissues surrounding well-drained and medically controlled fistulas has had promising results [54] (grade A) which need confirmation by other teams before recommendation. As a last option in severe AFCD, colostomy may be indicated, possibly combined with proctectomy if there is refractory rectal involvement after failure of other medical and surgical treatments, or if cancer is suspected.

Key points in the treatment of complex anal fistula

After prolonged loose-seton drainage of complex AFCD, and after obtaining luminal and perineal remission with anti-TNF ± immunosuppressive therapy (considered on a case-by-case basis), surgical treatment options are simple removal of seton and rectal advancement flap |

Anorectovaginal fistula in CD (ARVFCD)

Ciprofloxacin can be recommended for early treatment of inflammatory symptomatic anal fistula during the first weeks of induction therapy with biologics (grade B). TNF antagonists are the most effective treatment of complex anal fistulas, particularly in the case of ARVFCD, and combined use with an immunosuppressive agent should be discussed on a case-by-case basis. The efficacy of infliximab is inferior and less sustained for ARVFCD than for other types of perianal fistulas [32]. Fistulotomy is contraindicated due to secondary anatomic and functional muscle damage. Conservative techniques such as biological glue have not demonstrated a significantly superior efficacy to simple seton removal in patients not receiving anti-TNF therapy [47] (grade A). The technique of fistula resection and reconstruction has not been evaluated for ARVFCD and is not recommended because of the risk of complications (IE). LIFT has not been evaluated for ARVFCD and cannot be recommended based on current data. As rectal or vaginal advancement flap results are variable, they cannot be routinely recommended. The technique of interposition of a vascularized gracilis muscle flap or the Martius procedure is indicated for ARVFCD after failure of conservative surgery [55,56,57,58] (grade C). There are no current data to favor one technique over the other. Proctectomy with intersphincteric amputation is indicated as a last option for severe ARVFCD with refractory rectal involvement after failure of other medical and surgical treatment [59]. While it results in improved quality of life, it is nevertheless associated with a 20% risk of persistent perineal sinus that may be difficult to manage [55]. The role of stomal diversion for ARVFCD has been widely discussed in the literature. While it enables a reduction in the activity of severe APC, the rate of restoration of digestive continuity remains low [60]. Considering the major tissue destruction and rearrangements of the Martius procedure or graciloplasty, it seems preferable to associate a proximal stomal diversion when performed, but the optimal site of this diversion was never been formally demonstrated.

Key points in the treatment of ARVFCD

After prolonged seton drainage of ARVFCD, and after obtaining luminal and perineal remission with anti-TNF ± immunosuppressive therapy (considered case-by-case), surgical treatment options are simple seton removal and rectal or vaginal advancement flap (IE); | |

In case of failure of one or two advancement flap procedures, a Martius flap interposition or a graciloplasty should be considered (grade C); | |

Colostomy is indicated as a last option for severe ARVFCD possibly associated with a proctectomy if there is refractory rectal involvement after failure of other medical and surgical treatments (IE) |

Anorectal stricture in CD (ARSCD)

Fibrotic ARSCD usually occurs as a result of chronic inflammation and often occurs late in the course of the disease. The 1992 Cardiff classification [8] distinguishes Type 1 inflammatory stricture that relaxes under anesthesia and is amenable to medical treatment, from Type 2 fibrotic stricture which does not respond to medical treatment. The risk of colonic and anorectal dysplasia increases with the duration and severity of CD; the possibility of local or associated upstream dysplasia must always be investigated. The evaluation of ARSCD requires a physical examination, sometimes under anesthesia, plus endoscopy with biopsies and MRI to describe the stenosis itself, to identify associated inflammatory, infectious or dysplastic lesions, and to search for injury or fibrosis of the sphincter. Therapeutic strategy for ARSCD requires medical–surgical cooperation. Treatment with dilation is simple and minimally invasive; if feasible, it is proposed as first-line therapy for short symptomatic fibrotic strictures (grade C). Dilation can be proposed in cases of doubtful diagnosis in order to perform biopsies of the stenotic area or to perform an endoluminal examination (IE). There is a real risk of inducing incontinence by dilating the stricture in these patients with fibrotic lesions or of destroying the anal sphincter. Therefore, it is appropriate to assess the risk of anal incontinence before performing a dilation of anorectal stenosis (IE). If dilation of ARSCD is unsuccessful, conservative surgical alternatives should be studied before considering anoproctectomy (IE). These techniques are only possible in the absence of luminal inflammatory damage and are, in fact, rarely performed. They have not been evaluated to date. Moreover, where dysplasia or cancer is identified, proctectomy should be proposed (IE) [61, 62]. A proposed algorithm for management of anal stenosis is outlined in Fig. 2.

Conclusions

The management of anorectal CD should involve a multidisciplinary approach combining the knowledge of the gastroenterologist, the colorectal surgeon and the radiologist who have appropriate experience in this area. Lack of data about spontaneous evolution of primary lesions, about prognostic factors in more complex lesions, and the wide range of available medical and surgical procedures explains why these recommendations have only been partially associated with an elevated rating grade. Future work should include assessment of patient preferences, quality of life and anal continence. This national consensus work should be repeated at a future date when more data and stronger prognostic indicators may be available.

References

Lapidus A, Bernell O, Hellers G, Lofberg R (1998) Clinical course of colorectal Crohn’s disease: a 35-year follow-up study of 507 patients. Gastroenterology 114:1151–1160

Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendres JP, Cosnes J (2006) Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 130:650–656

Schwartz DA, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ et al (2002) The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 122:875–880

Hellers G, Bergstrand O, Ewerth S, Holmstrom B (1980) Occurrence and outcome after primary treatment of anal fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Gut 21:525–527

Gionchetti P et al (2017) 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: part 2: surgical management and special situations. J Crohns Colitis 11:135–149

Gecse KB et al (2014) A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut 63:1381–1392

Pellino G et al (2015) A think tank of the Italian society of colorectal surgery (SICCR) on the surgical treatment of inflammatory bowel disease using the Delphi method: Crohn’s disease. Tech Coloproctol 19:639–651

Hughes LE (1992) Clinical classification of perianal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 35:928–932

Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB (2003) American Gastroenterological association clinical practice committee. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 125:1508–1530

Irvine EJ (1995) Usual therapy improves perianal Crohn’s disease as measured by a new disease activity index. McMaster IBD study group. J Clin Gastroenterol 20:27–32

Beets-Tan RGH, Beets GL, van der Hoop AG et al (2001) Preoperative MR imaging of anal fistulas: does it really help the surgeon? Radiology 218:75–84

Schratter-Sehn AU, Lochs H, HandI-Zeller L, Tscholakoff D, Schratter M (1993) Endosonographic features of the lower pelvic region in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 88:1054–1057

Pescatori M, Interisano A, Basso L (1995) Management of perianal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 38:121–124

McKee RF, Keenan RA (1996) Perianal Crohn’s disease: is it all bad news? Dis Colon Rectum 39:136–142

Committee American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice (2003) American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 125:1503–1507

Tang LY, Rawsthorne P, Bernstein CN (2006) Are perineal and luminal fistulas associated in Crohn’s disease? A population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4:1130–1134

Maccioni F, Colaiacomo MC, Stasolla A, Manganaro L, Izzo L, Marini M (2002) Value of MRI performed with phased-array coil in the diagnosis and preoperative classification of perianal and anal fistulas. Radiol Med 104:58–67

Lunniss PJ, Barker PG, Sultan AH et al (1994) Magnetic resonance imaging of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 37:708–718

de Souza NM, Hall AS, Puni R, Gilderdale DJ, Young IR, Kmiot WA (1996) High resolution magnetic resonance imaging of the anal sphincter using a dedicated endo-anal coil. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging with surgical findings. Dis Colon Rectum 39:926–934

Schwartz DA, Wiersema MJ, Dudiak KM et al (2001) A comparison of endoscopic ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and exam under anesthesia for evaluation of Crohn’s perianal fistulas. Gastroenterology 121:1064–1072

Chapple KS, Spencer JA, Windsor AC et al (2000) Prognostic value of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of fistula in ano. Dis Colon Rectum 43:511–516

Buchanan GN, Halligan S, Bartram CI, Williams AB, Tarroni D (2004) Clinical examination, endosonography, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of fistula in ano: comparison with outcome-based reference standard. Radiology 233:674–681

Cuenod CA, de Parades V, Siauve N et al (2003) MR imaging of ano-perineal suppurations. J Radiol 84:516–528

Low RN, Sebrechts CP, Politoske DA et al (2002) Crohn disease with endoscopic correlation: single-shot fast spin-echo and gadolinium-enhanced fat-suppressed spoiled gradient-echo MR imaging. Radiology 222:652–660

Florie J, Wasser MN, Arts-Cieslik K, Akkerman EM, Siersema PD, Stoker J (2006) Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of the bowel wall for assessment of disease activity in Crohn’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 186:1384–1392

Van Assche G, Vanbeckevoort D, Bielen D et al (2003) Magnetic resonance imaging of the effects of infliximab on perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 98:332–339

Mallouhi A, Bonatti H, Peer S, Lugger P, Conrad F, Bodner G (2004) Detection and characterization of perianal inflammatory disease: accuracy of transperineal combined gray scale and colour Doppler sonography. J Ultrasound Med 23:19–27

Zbar AP, Oyetunji RO, Gill R (2006) Transperineal versus hydrogen peroxide-enhanced endo-anal ultrasonography in never operated and recurrent cryptogenic fistula in ano: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol 10:297–302

Domkundwar SV, Shinagare AB (2007) Role of transcutaneous perianal ultrasonography in evaluation of fistulas in ano. J Ultrasound Med 26:29–36

Maconi G, Ardizzone S, Greco S, Radice E, Bezzio C, Bianchi Porro G (2007) Transperineal ultrasound in the detection of perianal and rectovaginal fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 102:2214–2219

Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S et al (1999) Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 340:1398–1405

Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN et al (2004) Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 350:876–885

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ (2012) Perianal Crohn’s disease findings other than fistulas in a population-based cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis 18:43–48

Eglinton TW, Roberts R, Pearson J et al (2012) Clinical and genetic risk factors for perianal Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 107:589–596

Siproudhis L, Mortaji A, Mary JY, Juguet F, Bretagne JF, Gosselin M (1997) Anal lesions: any significant prognosis in Crohn’s disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:239–243

Cosnes J, Bourrier A, Laharie D et al (2013) Early administration of azathioprine vs. conventional management of Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 145:758–765

Ouraghi A, Nieuviarts S, Mougenel JL et al (2001) Infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease ano-perineal lesions. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 25:949–956

Bouguen G, Trouilloud I, Siproudhis L et al (2009) Long-term outcome of non-fistulizing (ulcers, stricture) perianal Crohn’s disease in patients treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 30:749–756

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W et al (2010) Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 362:1383–1395

Colombel J-F, Schwartz DA, Sandborn WJ et al (2009) Adalimumab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut 58:940–948

Dewint P, Hansen BE, Verhey E et al (2014) Adalimumab combined with ciprofloxacin is superior to adalimumab monotherapy in perianal fistula closure in Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial (ADAFI). Gut 63:292–299

Bell SJ, Williams AB, Wiesel P, Wilkinson K, Cohen RC, Kamm MA (2003) The clinical course of fistulating Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 17:1145–1151

Tanaka S, Matsuo K, Sasaki T, Nakano M, Sakai K, Beppu R et al (2010) Clinical advantages of combined seton placement and infliximab maintenance therapy for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: when and how were the seton drains removed? Hepatogastroenterology 57:3–7

Bouguen G, Siproudhis L, Gizard E et al (2013) Long-term outcome of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11:975–981

Buchanan GN, Owen HA, Torkington J, Lunniss PJ, Nicholls RJ, Cohen CR (2004) Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg 91:476–480

Haggett PJ, Moore NR, Shearman JD, Travis SP, Jewell DP, Mortensen NJ (1995) Pelvic and perineal complications of Crohn’s disease: assessment using magnetic resonance imaging. Gut 36:407–410

Grimaud JC, Munoz-Bongrand N, Siproudhis L et al (2010) Fibrin glue is effective healing perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 138:2275–2281

Senéjoux A, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L et al (2016) Fistula plug in fistulising ano-perineal Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis 10(2):141–148

Soltani A, Kaiser AM (2010) Endorectal flap for cryptoglandular or Crohn’s fistula in ano. Dis Colon Rectum 53:486–495

Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W et al (2010) The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: special situations. ECCO J Crohn’s Colitis 4:63–101

Reenaers C, Louis E, Belaiche J et al (2012) Does co-treatment with immunosuppressors improve outcome in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with adalimumab? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 36:1040–1048

Gingold DS, Murrell ZA, Fleshner PR (2014) A prospective evaluation of the ligation of the intersphincteric tract procedure for complex anal fistula in patients with Crohn disease. Ann Surg 260:1057–1061

Ruffolo C, Scarpa M, Bassi N, Angriman I (2010) A systematic review on advancement flaps for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease: transrectal vs. transvaginal approach. Colorectal Dis 12:1183–1191

Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G et al (2016) Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet 388:1281–1290

Lefevre JH, Bretagnol F, Maggiori L, Alves A, Ferron M, Panis Y (2009) Operative results and quality of life after gracilis muscle transposition for recurrent rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 52:1290–1295

Furst A, Schmidbauer C, Swol-Ben J, Iesalnieks I, Schwandner O, Agha A (2008) Gracilis transposition for repair of recurrent anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 23:349–353

Pitel S, Lefevre JH, Parc Y, Chafai N, Shields C, Tiret E (2011) Martius advancement flap for low rectovaginal fistula: short- and long-term results. Colorectal Dis 13:e112–e115

Songne K, Scotte M, Lubrano J, Huet E, Lefebure B, Surlemont Y et al (2007) Treatment of anovaginal or rectovaginal fistulas with modified Martius graft. Colorectal Dis 9:653

Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Marteau P, Benoist S, Valleur P (1999) Surgical treatment of ano-perineal Crohn’s disease: can abdominoperineal resection be predicted? J Am Coll Surg 189:171–176

Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Cazaban L et al (2001) Long-term results of faecal diversion for refractory perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 3:232–237

Annese V et al (2015) European evidence-based consensus: inflammatory bowel disease and malignancies. J Crohns Colitis 9:945–965

Rieder F et al (2016) European Crohn’s and colitis organisation topical review on prediction, diagnosis and management of fibrostenosing Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 10:873–885

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This type of study does not need ethical approval.

Informed consent

This type of study does not need informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bouchard, D., Abramowitz, L., Bouguen, G. et al. Anoperineal lesions in Crohn’s disease: French recommendations for clinical practice. Tech Coloproctol 21, 683–691 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-017-1684-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-017-1684-y