Abstract

Background

Our specific aim was to investigate the prognostic value of effective duration of first androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and to evaluate the clinical impact on early docetaxel administration with oncological outcomes in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients treated with docetaxel.

Methods

We identified 148 mCRPC patients who were treated with 75 mg/m2 docetaxel. We defined 16 months as the threshold for the effective duration of ADT, and defined 12 months as the cut-off time for starting docetaxel from the onset of CRPC. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to investigate the prognostic indicators that influenced the survival outcomes.

Results

Overall, 81 (54.7%) patients died. The median 1st ADT response was 22.2 months and the median time interval from CRPC onset to docetaxel treatment was 11.7 months. Multivariate analysis indicated that visceral metastasis, bone metastasis extent of disease (EOD) ≥ 2, and effective duration of ADT < 16 months were the independent prognostic indicators for progression-free survival (PFS). Referring to cancer-specific survival (CSS), besides visceral metastasis and effective duration of ADT < 16 months, late docetaxel treatment ≥ 12 months became as the predictors for poor prognosis. Among the ADT poor-responder group (ADT < 16 months), Kaplan–Meier method showed that 1-year and 2-year CSS rates were 96.0% and 80.0% in the patients who introduced docetaxel in early setting (< 12 months), which were significantly higher than those who introduced in late settings (93.6% and 30.8%, respectively, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

CRPC patients who had poor response during 1st ADT would obtain survival benefit by introducing docetaxel treatment in early stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In patients with advanced prostate cancer, it is of key importance to select appropriate therapeutic agents from amongst the evolving treatment options for controlling inevitable tumor progression. Despite the initial success of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), almost all patients progress over a certain period to a more aggressive and lethal stage, known as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [1, 2]. The combination of docetaxel and corticosteroid was introduced as an effective treatment with a demonstrated survival benefit in CRPC patients, which was found in the TAX327 trial [3]. New androgen receptor (AR) targeting agents, e.g., enzalutamide and abiraterone acetate [4, 5], second-line cytotoxic agents, e.g., cabazitaxel [6], and the bone targeting alpha emitter radium-223 [7] have all been introduced as alternative treatment options for metastatic CRPC (mCRPC), but the treatment efficacy is still limited for highly advanced CRPC men and eventually progress to cancer death.

Thus, every three-week docetaxel plus predonisone is still positioned as the first-line chemotherapy for obtaining the clinical benefit in CRPC. To consider appropriate docetaxel introduction for CRPC, several known prognostic models have been identified; including baseline prostate-specific antigen (PSA), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), hemoglobin level, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR), absolute monocyte count (AMC), performance status (PS), presence of visceral or liver metastases, Gleason Score, clinical pain, albumin, and circulating tumor enumeration [8,9,10,11]. Although numerous prognostic factors have been reported, these literatures do not set a course for recommending who to use docetaxel for first-line treatment after the onset of being castration resistant.

Based upon this scenario, some investigators have focused on the duration of response to 1st ADT for predicting oncologic outcomes for CRPC patients who were treated with docetaxel [12]. Moreover, one literature also reported that effective duration of ADT was the strongest parameter for determining the cancer-specific survival (CSS) in CRPC patients who were treated with abiraterone acetate [13, 14]. However, there is scarce information about when to decide in exact timing for selecting docetaxel therapy to obtain the best clinical benefit per individual after 1st ADT failure. Since the implication of the response duration during ADT has not been fully characterized, we conducted a retrospective analysis of CRPC patients who were treated with first-line docetaxel to determine whether or not the duration of the response to 1st ADT and time to start docetaxel affected further clinical and survival outcomes.

Our specific aim in this study was to investigate the correlation of the prognostic value of effective duration of 1st ADT and the clinical impact on the timing of docetaxel administration with oncological outcomes in CRPC men treated with docetaxel.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board in Keio University Hospital. Between April 2007 and March 2014, before approval of new AR-targeting drugs in Japan, we identified total of 148 patients who were diagnosed with metastatic CRPC (mCRPC) and were treated with first-line docetaxel. All patients were histologically confirmed as having adenocarcinoma of the prostate with clinical or radiological evidence of metastatic disease, and showed disease progression during 1st ADT. The duration response to ADT was defined as the time between the start date of first hormonal therapy, including luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LH–RH) analog, anti-androgen, or both, and the date with first evidence of disease progression (biochemical or radiological). We defined the lowest serum PSA level during ADT as PSA nadir. PSA doubling time (PSADT) was also measured as an indication for tumor aggressiveness during ADT.

CRPC was defined as a disease that progresses on ADT despite castrate serum testosterone levels (50 ng/mL) and may present as either a continuous rise in serum PSA levels, progression of pre-existing disease, or appearance of new metastases [15]. We also calculated the duration from the time the patient was diagnosed with CRPC to the primary date of docetaxel treatment. During this period, patients were mainly treated using an alternative antiandrogen therapy, corticosteroids, which lead to antiandrogen-withdrawal syndrome, or closely observed by evaluating PSA level.

All patients received first-line docetaxel 75 mg/m2 administered intravenously on day 1 of each treatment cycle. No prior chemotherapy regimens or androgen receptor (AR) targeting agents were administered before docetaxel treatment. Objective data from the day before administration of the primary docetaxel treatment were collected retrospectively, including patient background, pertinent laboratory values, and radiological findings. For bone scan results, the number or extent of metastases were divided into five extent of disease (EOD) grades.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from docetaxel to any disease progression, such as an increase in PSA value ≥ 25% relative to the pretreatment PSA value or radiological progression according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines [16]. To minimize the time-leading bias, CSS was defined as the time from the first diagnosis of CRPC to the date of death related to prostate cancer.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier (KM) method was used to estimate event-time distributions of PFS and CSS using the log rank test to assess significance. Univariate Cox regression models were used to adjust for potential confounders in predicting PFS and CSS. For all continuous variables, we conducted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to explore the optimal cut-off points and determined the most appropriate amounts as categorical parameters so as to adapt them for univariate and multivariate analyses. After performing ROC analysis, we defined 16 months as the threshold for the effective duration of ADT and 12 months as the time interval for starting docetaxel from the onset of CRPC as the optimal cut-off point (duration of ADT; area under curve [AUC] 0.701, p < 0.001, time to start of docetaxel; AUC 0.667, p = 0.001). Categorical variables, including clinical pathological parameters were assessed in multivariate models using a Cox proportional hazard regression model with a stepwise forward selection method. For all statistical analyses, tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Our study was based upon the statistical Package of Social Sciences version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristic of the study cohort is shown in Table 1. The median age was 75 (52–95) years and the median follow-up period was 48.0 (3.3–94.9) months. Among the whole population, 89 (60.1%) patients were able to continue ADT for longer than 16 months, whereas 59 (39.9%) patients were unable to continue first ADT for 16 months. The median number of cycles of docetaxel treatment was 9 (3–46). According to the pathological findings, 55 (37.2%) patients were diagnosed with a Gleason Score ≥ 9, classified as group 5. Bone metastasis was detected in 99 (66.9%) patients, and 63 (42.6%) patients were diagnosed with an EOD score ≥ 2. In assessing lymph node/distant metastasis, 34 (23.0%) patients were found to have lymph node metastasis, whereas visceral metastases were detected in 31 (20.9%) patients. After first ADT began, 68 (45.9%) patients reached a PSA nadir < 0.2 ng/mL. The median duration of ADT was 22.2 (7.0–63.6) months. Moreover, the median time to the start of docetaxel treatment from CRPC onset was 11.7 (0.1–60.9) months. Overall, 81 (54.7%) patients died from CRPC. The median values of PFS and CSS were 16.7 (2.4–84.1) months and 28.8 (3.3–94.9) months, respectively.

The association between 1st ADT response and PFS (from the start of docetaxel), and CSS (from diagnosis of CRPC)

Table 2 indicates the result of the univariate and multivariate analyses with regard to PFS. From the univariate analysis, nadir PSA during ADT ≥ 0.2 ng/mL, PSA doubling time < 6 months, EOD score ≥ 2, visceral metastasis, effective duration of ADT < 16 months, PSA before docetaxel ≥ 20 ng/mL, Hb < 10 mg/dL, and ALP ≥ 279 U/L were significantly associated with shorter PFS. The multivariate analysis revealed that EOD score ≥ 2 (HR = 1.84, p = 0.011), visceral metastasis (HR = 1.72, p = 0.037), and duration of ADT response < 16 months (HR = 2.54, p < 0.001) were the independent prognostic indicators for PFS.

Referring to CSS, nadir PSA during ADT ≥ 0.2 ng/mL, PSA doubling time < 6 months, EOD score ≥ 2, visceral metastasis, effective duration of ADT < 16 months, long time interval to start docetaxel ≥ 12 months, PSA before docetaxel ≥ 20 ng/mL, Hb < 10 mg/dL, and ALP ≥ 279 U/L showed significant association with poor CSS. According to the multivariate analysis, visceral metastasis (HR = 2.97, p < 0.001), effective duration of ADT < 16 months (HR = 2.64, p < 0.001), time interval to start docetaxel ≥ 12 months (HR = 1.70, p = 0.022), and PSA before docetaxel ≥ 20 ng/mL (HR = 2.15, p = 0.004) were shown to be the independent prognostic factors for CSS (Table 3).

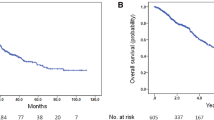

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the survival differences of PFS and CSS classified by the effective duration of ADT. Figure 1 shows the PFS rate compared with ADT response ≥ 16 months and ADT response < 16 months. These results indicated that 1- and 2-year PFS rates were 68.1% and 41.9% in patients who responded for ≥ 16 months, which was significantly higher than less than those in the ADT < 16 months(22.0% and 0%, respectively, p = 0.024). According to Fig. 2, the 1- and 2-year CSS rates were 96.6% and 91.6%, respectively, in patients with an effective duration of ADT ≥ 16 months, which were significantly higher than those in the ADT < 16 months group (96.6%, and 54.0%, respectively, p < 0.001).

To confirm the clinical value of early docetaxel administration, we further conducted a subgroup analysis dividing the cohort into ADT responder (ADT ≥ 16 months) and poor-responder (ADT < 16 months) groups. Among the poor-responder group, multivariate analysis demonstrated that the presence of visceral metastasis (HR = 2.98, p = 0.005) and time interval to the start of docetaxel ≥ 12 months (HR = 2.14, p = 0.030) remained as the independent prognostic factors for CSS (Supplemental Table 1). Neither PSA nadir level nor PSA doubling time had significant association for predicting further CSS. In contrast, however, no significant differences were shown for PFS with time of onset of docetaxel treatment in the ADT responder group (Supplemental Table 2).

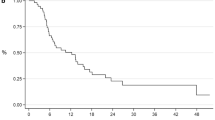

As shown in Fig. 3a, b, we illustrated KM method classifying the ADT responder group and ADT poor-responder group with time interval of docetaxel introduction. The period of time to starting docetaxel did not show any survival benefit in the ADT ≥ 16 months group (p = 0.322). However, we found that patients who had poor response in 1st ADT (ADT < 16 months) significantly showed better survival by early docetaxel introduction (docetaxel treatment < 12 months from CRPC onset) compared with those who extended the period from CRPC onset to docetaxel treatment to more than 12 months (1- and 2-year survival rates were 96.0% and 80.0%, respectively, whereas the counterpart was 93.6% and 30.8%, respectively, p < 0.001).

a Kaplan–Meier estimates of CSS in men with ADT poor-responded group classified by time interval to the start of docetaxel; DTX ≥ 12 months and DTX < 12 months. b Kaplan–Meier estimates of CSS in men with ADT well responded group classified by time interval to the start of docetaxel; DTX ≥ 12 months and DTX < 12 months

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that a shorter effective duration of ADT and longer time interval to the start of docetaxel treatment from CRPC onset resulted in poorer survival outcomes. Furthermore, our data suggested that CRPC patients who had poor response on 1st ADT had certain clinical benefit by early docetaxel introduction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the clinical value of early administration of docetaxel for CRPC men who had poor response on 1st ADT.

We clearly demonstrated the length of the ADT response significantly influenced survival outcomes in CRPC patients including PFS and CSS in this study, as previously shown [14]. The effective duration of ADT also showed the highest statistical power compared with well-known prognostic factors. As previous literature demonstrated, it was suggested that patients who responded poorly to first ADT may overtake the malignant potential after the patient becomes castration resistant, which could affect the further therapeutic effect of docetaxel treatment [17]. One previous study explained that a shorter effective period of first ADT may influence the clinical outcome of docetaxel treatment, because taxanes are postulated to have cytotoxic effect on prostate cancer cells, in part, through their impact on androgen receptor signaling [18]. Taking these evidences into consideration, our data also followed the previous findings that the treatment response on 1st ADT becomes one of the key indicators for predicting the treatment response of docetaxel in CRPC patients.

In this study, however, we found that there was a tendency that the time to the start of docetaxel strongly correlated with the further therapeutic efficacy of docetaxel treatment. Because this study included only pure docetaxel setting for first-line treatment in CRPC patients, clinicians have challenged alternative hormonal therapies for controlling PSA level after ADT failure; such as using alternative androgen therapy [19], observing PSA for the expected androgen withdrawal syndrome [20], or continue treating with low-dose steroid therapy for further disease control [21]. Since these subsequent therapies were shown to have clinical efficacy to some extent after 1st ADT, the time to the start of docetaxel often varied among our cohort. According to the Cox regression analysis, it revealed that the longer time interval for docetaxel from CRPC onset resulted in poorer CSS, so we found that not only the duration of response to 1st ADT but also the interval to the start of docetaxel strongly need to be considered as crucial factors for predicting the therapeutic effect of docetaxel treatment.

In 2015, the randomized controlled study the so-called CHAARTED trial, emerged to demonstrate the clinical efficacy of administering docetaxel plus 1st ADT in hormone sensitive metastatic prostate carcinoma [22]. This novel study indicated that docetaxel was proved to become the key cytotoxic drug to prolong overall survival even in hormone naïve settings. In particular, they also emphasized the exceptional value of docetaxel for high-volume diseases, which was defined as patients with visceral metastases or 4 or more bone metastatic lesions. Although this study was conducted to hormone sensitive prostate cancer patients, it suggested that early administration of docetaxel promised a clinical benefit among patients especially for advanced prostate carcinoma. Given the trend of introducing docetaxel treatment in accelerated schedule for prostate cancer men [23, 24], it may be feasible to take precedence to choose docetaxel as first treatment option especially for CRPC men who have aggressive feature.

To confirm the clinical impact of early docetaxel administration, we further conducted a subgroup analysis dividing the cohort into ADT responder and non-responder groups. Among the ADT poor-responded groups, it indicated that early docetaxel administration had certain clinical benefit. This result suggested that early docetaxel usage could become more beneficial in ADT poor-responder patients than challenging classical secondary hormonal therapies before docetaxel treatment for patients with early CRPC. Because there were several cases that showed poor prognosis because of delayed docetaxel administration over concerns about severe adverse effects [10], the 12 month cut-off of docetaxel may provide useful information for clinicians to be aware of when deciding on primary docetaxel treatment. Given the current treatment options for patients with CRPC, however, it is a challenging issue to determine the optimal docetaxel timing among patients with CRPC who were treated with 1st line AR-targeting agents. Still, there is no concrete evidence to support whether 1st line docetaxel is superior to 1st line AR agents for patients with CRPC [25]. Therefore, further prospective investigation is warranted to clarify the true position of docetaxel usage.

We acknowledge several limitations in our study. First, the study design was retrospective and involved a relatively small population. Second, we did not include patients who received intermittent docetaxel treatment, which may have led to selection bias. Third, data were not available to allow collection for some known prognostic factors such as symptom level, number of comorbidities, serum albumin, and C-reactive protein. Last but not least, the entire population was identified at a time before the approval of new AR-targeting agents as treatment for patients with CRPC in Japan, so the study design was limited to docetaxel treatment only. Therefore, given the current situation with many more treatment options and sequential therapies available for patients with CRPC, the optimal timing of docetaxel usage should be discussed in light of the current treatment flow. However, the strength of our study is that the data comprise the real-world outcomes with 1st line docetaxel in Asian patients with CRPC analyzed in a relatively homogeneous population.

In conclusion, the treatment response to 1st ADT and time to the start of docetaxel from CRPC onset could be considered as key prognostic factors for CRPC patients treated with docetaxel. For those who had poor response on ADT, earlier docetaxel treatment may contribute to a certain survival benefit.

Change history

02 March 2019

The original article can be found online.

References

Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J et al (2014) EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part I: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent-update 2013. Eur Urol 65:124–137

Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J et al (2014) EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol 65:467–479

Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR et al (2004) Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 351:1502–1512

Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS et al (2013) Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 368:138–148

Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE et al (2014) Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 371:424–433

de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M et al (2010) Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet 376:1147–1154

Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D et al (2013) Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 369:213–223

Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer ES, Yang YC et al (2007) A contemporary prognostic nomogram for men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer: a TAX327 study analysis. Clin Cancer Res 13:6396–6403

Halabi S, Lin CY, Small EJ et al (2013) Prognostic model predicting metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer survival in men treated with second-line chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:1729–1737

Shigeta K, Kosaka T, Kitano S et al (2016) High absolute monocyte count predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with castration-resistant Prostate cancer treated with docetaxel chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 23:4115–4122

de Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB et al (2008) Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14:6302–6309

van Soest RJ, Templeton AJ, Vera-Badillo FE et al (2015) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy: data from two randomized phase III trials. Ann Oncol 26:743–749

Giacinti S, Carlini P, Roberto M et al (2017) Duration of response to first androgen deprivation therapy, time to castration resistance prostate cancer, and outcome of metastatic castration resistance prostate cancer patients treated with abiraterone acetate. Anticancer Drugs 28:110–115

Hongo H, Kosaka T, Mizuno R et al (2016) Should we try antiandrogen withdrawal in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients? Insights from a retrospective study. Clin Genitourin Cancer 14:e569–e573

Scher HI, Morris MJ, Stadler WM et al (2016) Trial design and objectives for castration-resistant prostate cancer: updated recommendations from the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3. J Clin Oncol 34:1402–1418

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA et al (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216

Halabi S, Small EJ, Kantoff PW et al (2003) Prognostic model for predicting survival in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 21:1232–1237

Halabi S, Lin CY, Kelly WK et al (2014) Updated prognostic model for predicting overall survival in first-line chemotherapy for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:671–677

Suzuki H, Okihara K, Miyake H et al (2008) Alternative nonsteroidal antiandrogen therapy for advanced prostate cancer that relapsed after initial maximum androgen blockade. J Urol 180:921–927

Sartor AO, Tangen CM, Hussain MH et al (2008) Antiandrogen withdrawal in castrate-refractory prostate cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial (SWOG 9426). Cancer 112:2393–2400

Kantoff PW, Halabi S, Conaway M et al (1999) Hydrocortisone with or without mitoxantrone in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: results of the cancer and leukemia group B 9182 study. J Clin Oncol 17:2506–2513

Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M et al (2015) Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 373:737–746

Vale CL, Burdett S, Rydzewska LH et al (2016) Addition of docetaxel or bisphosphonates to standard of care in men with localised or metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analyses of aggregate data. Lancet Oncol 17:243–256

Bracarda S, Caserta C, Galli L et al (2015) Docetaxel rechallenge in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: any place in the modern treatment scenario? An intention to treat evaluation. Future Oncol 11:3083–3090

Sonpavde G, Huang A, Wang L et al (2018) Taxane chemotherapy vs antiandrogen agents as first-line therapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. BJU Int 121:871–879

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (#17K11158) and the Prostate Research Fund in Japan. The study was supported in part by research Grants to T. Kosaka from the Takeda Science Foundation, Japan, the Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology and the Yamaguchi Endocrine Research Foundation. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: In the Original Publication, Tables 2 and 3 have been published with “###” instead of numerical values. Also in Table 2, the bold entries are made unbold. The errors have been occurred at Publishers end. The tables have been corrected.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Shigeta, K., Kosaka, T., Hongo, H. et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer patients who had poor response on first androgen deprivation therapy would obtain certain clinical benefit from early docetaxel administration. Int J Clin Oncol 24, 546–553 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-018-01388-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-018-01388-5