Abstract

Chronic subdural hematomas (CSDH) are increasingly prevalent, especially among the elderly. Surgical intervention is essential in most cases. However, the choice of surgical technique, either craniotomy or burr-hole opening, remains a subject of debate. Additionally, the risk factors for poor long-term outcomes following surgical treatment remain poorly described. This article presents a 10-year retrospective cohort study conducted at a single center that aimed to compare the outcomes of two common surgical techniques for CSDH evacuation: burr hole opening and minicraniotomy. The study also identified risk factors associated with poor long-term outcome, which was defined as an mRS score ≥ 3 at 6 months. This study included 582 adult patients who were surgically treated for unilateral CSDH. Burr-hole opening was performed in 43% of the patients, while minicraniotomy was performed in 57%. Recurrence was observed in 10% of the cases and postoperative complications in 13%. The rates of recurrence, postoperative complications, death and poor long-term outcome did not differ significantly between the two surgical approaches. Multivariate analysis identified postoperative general complications, recurrence, and preoperative mRS score ≥ 3 as independent risk factors for poor outcomes at 6 months. Recurrence contribute to a poorer prognosis in CSDH. Nevertheless, use burr hole or minicraniotomy for the management of CSDH showed a similar recurrence rate and no significant differences in post-operative outcomes. This underlines the need for a thorough assessment of patients with CSHD and the importance of avoiding their occurrence, by promoting early mobilization of patients. Future research is necessary to mitigate the risk of recurrence, regardless of the surgical technique employed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) evacuation is one of the most frequent neurosurgical procedures owing to its increasing prevalence, particularly among the elderly population [29]. Its occurrence is often associated with predisposing factors such as anticoagulant therapy, or coagulopathies [4, 5]. The pathophysiology of CSDH is characterized by the gradual accumulation of blood between the dura mater and the arachnoid membrane. This insidious process, driven by bleeding from bridging veins or minor head injuries, can result in increased intracranial pressure, neurologic deficits, and potentially life-threatening complications [8, 9]. Therefore, timely intervention is essential for CSDH management.

When asymptomatic, initial management of CSDH can involve conservative approaches, such as observation or medical management with corticosteroids or anticoagulant reversal agents [15]. However, surgical intervention is necessary in many cases, particularly when hematoma causes a significant mass effect or neurological deterioration [13, 27]. Neurosurgeons are faced with the choice of surgical techniques, craniotomy [1], or burr hole opening [19], to evacuate the hematoma. The selection of the optimal surgical technique for CSDH management remains a subject of ongoing debate in the neurosurgical community. Most systematic reviews and meta-analyses report heterogeneous data from centers with different perioperative practices, underlining the scarcity of robust evidence in the literature [2, 13, 18]. In addition, the risk factors for poor long-term outcome after surgical treatment are poorly described in the literature.

This article focuses on a 10-year retrospective cohort study conducted at a single center aimed at comparing the outcomes of two commonly employed surgical techniques for CSDH evacuation: burr hole opening and minicraniotomy. Through an analysis of patient records and follow-up data, we aimed to shed light on the postoperative complications associated with each approach, evaluate the recurrence rates following surgery in a large homogeneous series of patients with comparable perioperative practices, and identify the risk factors for long-term poor outcome.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a single-center, retrospective cohort study. We screened patients surgically treated for unilateral CSDH at our tertiary neurosurgical center between January 2012 and December 2022.

Participants

All adult patients with CSDH who underwent surgery with a burr hole or minicraniotomy were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows:1) bilateral CSDH hematoma, 2) previous surgery for CSDH within the last 6 months, and 3) insufficient data (no preoperative CT scan or operative report available).

Variables and data sources

The following clinical and radiological data were retrospectively collected by two investigators (SH et MS). Clinical data included age, sex, medical history and treatment (anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy), modified Rankin Scale (mRS), and clinical symptoms at diagnosis. Radiological data included the maximal thickness of the hematoma (mm) and maximum midline shift (mm), defined as the distance from the point of the septum pellucidum between the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles to a perpendicular line connecting the anterior and posterior insertions of the falx cerebri. Surgical data included the choice of the surgical approach (burr hole or minicraniotomy). Follow-up data included the occurrence of general postoperative complications (i.e. the occurrence of a surgical or medical complication within one month following surgery, including: surgical site infection, general infection, neurological deficit, recurrence or thromboembolic event), hematoma recurrence (defined by radiological recurrence with clinical symptoms requiring surgery), mRS at 6 months, and institutionalization. This study was conducted in compliance with the STROBE guidelines. Poor outcome was defined as an mRS score of ≥ 3 (i.e., disability requiring some help).

Surgical approaches

The choice of surgical approach depended exclusively on the surgeon: some surgeons performed minicraniotomy exclusively, while others performed only a burr hole. The skin incision was linear in all cases, and approximately 6 cm for the minicraniotomy versus 3 cm for burr-hole. The diameter of the minicraniotomy was 3 to 4 cm, versus 1,5 cm for the burr-hole. They were performed over the maximum thickness of the hematoma. All patients benefit from similar subdural drain placement (a one small 3 mm-diameter non-suction drain was placed in the subdural space), except in rare cases where drain insertion is impossible (i.e. when the cerebral cortex is too close to the skull bone, to avoid cerebral contusion).

Preoperative management

Anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy was stopped 5 days preoperatively, according to the guidelines of the French National Health Agency, except in life-threatening situations. In this case treatment was antagonized according to the substance: Antivitamins K were antagonized with vitamin K and PPSB, heparin with protamine sulfate and the new oral anticoagulants with PPSB alone. Antiplatelet therapy was not antagonized.

Postoperative management

In our center, all patients have similar postoperative management: Reverticalization was performed early, within 6 h of surgery: The patient is first raised at the bedside and takes a few steps with the help of a nurse and/or physiotherapist. The first day after the operation, the patient is up and walking with or without assistance, depending on his degree of autonomy. The drain was removed 2 days after surgery for all patient. Post-operative CT scan were not routinely performed, as the clinical relevance of this examination was low [23]. Discharge practices did not differ according to surgical approach. Preventive anticoagulation was introduced 2 days after surgery for all patients. Curative anticoagulation was reintroduced depending on the disease: 3 days for mechanical heart valves and pulmonary embolism < 6 months, 5 days for cardiac arrhythmia and 10 days in other cases. Antiplatelet therapy was reintroduced 5 days after surgery in the case of cardiac stents < 1 year, 10 days in the case of stents > 1 year or non-stented ischemic heart disease, and 30 days in other cases (stroke and primary prevention). In our center, corticosteroids were not used in postoperative management.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were carried out using Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests to compare categorical variables, and the Mann–Whitney rank sum test or unpaired t-test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Variables associated with mRS ≥ 3 at 6 months in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate logistic regression model. The candidate variates were included in a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operation (LASSO) penalized regression model. The penalty coefficient (lambda = 0.758) was chosen so as to provide an estimation error lower than one standard deviation of the minimum error obtained by 10-fold cross-validation, while being as parsimonious as possible. No variable had a coefficient different from 0 with this lambda coefficient. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

This study received the required authorization (CLERS 3339) from the institutional review board of our hospital. According to French legislation, the requirement for informed consent was waived for this observational retrospective study.

Results

Study population

During the inclusion period, 630 patients underwent surgery for evacuation of CSDH. Thirty-eight patients had bilateral CSDH, and 20 had undergone previous surgery for CSDH within the last 6 months. Preoperative CT-scan and/or operative reports were unavailable for 10 patients. In total, 582 patients were included in this study. A flowchart of the inclusion and exclusion of patients is shown in Fig. 1. The mean age at diagnosis was 74.6 ± 13.1 years (range 18–96). Men accounted for 74% of all the patients (n = 430).

Clinical and radiological findings

The clinico-radiological findings and group comparability are shown in Table 1. The median preoperative mRS score was 4 (IQ 3–4) and the median preoperative Glasgow score was 15 (IQ 14–15, range 6–15). The most frequent symptom was a motor deficit (n = 236, 41%), followed by headache (n = 117, 20%), neuropsychological disorder (n = 77, 13%), other (including sensitive disorder, disturbance and visual disorder, n = 76, 13%), aphasia (n = 52, 9%) and epileptic seizures (n = 24, 4%). Antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy was administered to 27% (n = 155) and 22% (n = 130) of patients, respectively. Radiological findings on CT scans were hypodense in 38% of cases (n = 219), followed by mixed (25%, n = 143), isodense (24%, n = 152), and septated (11%, n = 65). The mean maximal thickness of the hematoma was 20.5 ± 7.9 mm (range 4.2–40) and the mean maximal midline shift was 9.6 ± 5.6 mm (range 0–37). Clinical and radiological findings did not significantly differ between the two groups, except for the maximal midline shift that was more important in patients with burr hole opening (10.2 mm) than in patients who underwent minicraniotomy (9.2 mm, p = 0.02). Sixty-two patients underwent emergency surgery, including 16 treated with anticoagulant therapy and 21 with antiplatelet therapy. These patients were admitted to the intensive care unit within the first 24 h.

Intraoperative findings

Burr-hole opening was performed in 43% (n = 253) of the patients and minicraniotomy in 57% (n = 329). All patients, except 6% (n = 35), underwent subdural drain placement.

Postoperative outcomes

The postoperative outcomes and comparisons between the techniques are detailed in Table 2. Recurrence occurred in 10% (n = 57) of cases. General complications occurred in 13% (n = 74) of cases, including stroke (1%, n = 8), deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism (1%, n = 8), and myocardial ischemia (0.5%, n = 3). Surgical site infection occurred in 2% (n = 11) of the cases. Clinical data 1 month after surgery were available for 549 patients; of these,7% (n = 34) had neurological deficits, 6% (n = 32) were institutionalized, and 4% (n = 21) died. The mRS score at 6 months was < 3 in 78% (n = 397) of 506 patients. The rate of recurrence did not differ between the two surgical approaches, nor did the rates of general postoperative complications, surgical site infection, death, institutionalization, mRS score at 6 months, or persistence of neurological deficit at 1 month.

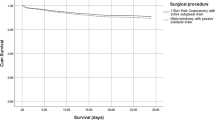

Risk factors of poor outcome

The risk factors for poor outcome (i.e., mRS score ≥ 3) are detailed in Table 3. In univariate analysis, age (p = 0.016), preoperative mRS score ≥ 3 (p < 0.01), maximal hematoma thickness (p = 0.03), recurrence (p < 0.001), and postoperative general complications (p < 0.001) were associated with poor outcome. Sex, first symptom at diagnostic, anticoagulant therapy, antiplatelet therapy, preoperative Glasgow score, radiological aspect on CT-scan, maximal midline shift, and surgical site infection were not significant risk factors for poor outcome. In the multivariate analysis, (age (OR, 1.02 [95%CI:1.00-1.05], p = 0.033), postoperative general complications (OR, 15.0 [95%CI:8.20–28.3], p < 0.001), recurrence (OR, 2.59 [95%CI:1.26–5.20], p < 0.01), and preoperative mRS score ≥ 3 (OR, 3.62 [95%CI:1.28–13.3], p < 0.01) were independent risk factors for poor outcome at 6 months. A forest plot of this multivariate analysis is shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Key results

In this retrospective monocentric study, which included 582 cases, we assessed the differences between surgical approaches for the treatment of CSDH and the risk factors associated with poor long-term outcomes following this surgery. Our findings indicate that.

(1) Burr-hole opening and minicraniotomy had similar rates of postoperative complications, including general postoperative complications, surgical site infections, death within 1 month, and institutionalization; (2) burr hole opening and craniectomy showed similar rates of recurrence; and (3) age, postoperative general complications, recurrence, and preoperative mRS score ≥ 3 were identified as independent risk factors for poor long-term outcomes.

Comparison between surgical approaches

In this retrospective analysis, we aimed to compare the postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing either surgical approach and to investigate the impact of recurrence on long-term functional outcomes. Our findings indicate that in terms of immediate postoperative outcomes, there were no statistically significant differences between the two surgical techniques. This result is not consistent with previous research in the field; Ducruet et al. showed in a meta-analysis that the complication rate was higher for patients who received a trepan hole than for those who underwent craniotomy, even though the mortality rate was higher in the craniotomy group [6]. In contrast, Weigel et al. showed that morbidity was higher after craniotomy, with a similar recurrence rate between the two techniques [27] and Almenawer et al. showed that craniotomy led to more complications but less recurrence [2]. In addition, a decision analysis model by Lega et al. using Monte Carlo simulation of meta-analysis data revealed that BHC was ultimately superior to craniotomy [17]. These results must be treated with caution, as the size of the craniotomy is not specified in these publications, yet the size of the craniotomy can influence the rate of postoperative complications. This is the strength of our study, in which the craniotomy size was similar for all patients (3–4 cm). One possible option, little discussed in the literature, is to make a trepan hole and convert it into a minicraniotomy in case of a solid clot. Our results underscore the notion that from a short-term perspective, either technique can be employed with a similar expectation of success in terms of complications and recurrence. The strength of our study lies in the homogeneous nature of our postoperative follow-up: all patients were up and about the evening of the operation, which is not always the case, particularly for minicraniotomy patients who are often referred for postoperative intensive care [1]. In the meta-analyses cited above, intraoperative practices varied, especially between minicraniotomy and burr hole, and may explain the differences observed. This underlines the importance, in our opinion, of early reverticalization of patients who are often frail and elderly. This may also explain our mortality rate, which is lower than that in other studies [15]. Indeed, reverticalization has been shown to reduce postoperative complications, without affecting recurrence [16, 21]. Twist drill is also an alternative whose complication rates seem to be similar to those of the burr hole and is less invasive [2, 13], but it appears to have a higher recurrence rate [7]. This technique should therefore be used with caution, since as we have shown, recurrence is an independent risk factor for poor clinical outcome. The role of endoscopy remains to be clarified, but recent studies tend to show that it can reduce recurrence but increase operating times and costs. However, its use does not appear to have any effect on long-term clinical outcome [3, 28].

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy

French guidelines recommend stopping antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy five days before surgery, except in cases of life-threatening situations. We showed that thrombotic and embolic events are rare (< 1%). This shows that the benefit/risk balance favors stopping these treatments before surgery. We have also shown that the use of anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet therapy is not a risk factor for recurrence, in line with the results of other studies [10, 22, 26]. Resumption of these treatments is therefore possible, depending on the thrombotic and/or embolic risk of the initial pathology.

Risk factors of poor outcome

Our study highlights a crucial factor that has not been extensively explored in the context of SDH management: the role of recurrence and postoperative complications as a predictor of long-term functional outcomes. Regardless of whether patients underwent burr hole trepanation or minicraniotomy, the presence of recurrent hematomas significantly increased the risk of having an mRS score greater than 3 at a later stage. This finding underscores the importance of considering the impact of recurrence in clinical decision making and the necessity for future research into strategies that minimize recurrence risk, irrespective of the chosen surgical method. These new data are absent from most series and literature reviews [15, 20]. Our study revealed that, beyond the risk of recurrence, the occurrence of postoperative complications constitutes a significant factor contributing to a poor prognosis (OR 15, p < 0.001). Corticosteroid treatment may contribute to postoperative complications, and its role in preventing recurrence remains a subject of debate in the literature. Two recent meta-analysis indicated that adjuvant corticosteroid therapy appeared effective in reducing the risk of recurrence but significantly elevated the risk of adverse events [11, 24]. These findings were further supported by the results of the DEX-CSDH clinical trial [12]. Our study does not allow us to draw any conclusions on this subject, as they are not used in our hospital, precisely to avoid adverse events. Implementing early mobilization of these patients should also be considered a standard practice for minimize the risk of general complications. When we compare our results in terms of morbidity and recurrence with the literature, we have a lower rate than most published series (20% recurrence in the Weigel’s series, 15% morbidity and recurrence in the Almenaver’s series [2, 27]). Moreover, recent data are in favor of early mobilization to accelerate patient recovery, whatever the type of surgery [25]. The prescription of corticosteroids is also associated with an increase in morbidity, particularly in this elderly population, as demonstrated by the DEX-CSDH clinical trial [12]. Our study is the first to show the significant long-term negative effect of recurrence in CSDH and supports the conclusions of a recent study on the association between medical complications and post-operative outcomes [14]. This encourages early mobilization of patients and avoidance of corticosteroids prescription.

Limitations

Although our study provides valuable insights into the outcomes of these surgical techniques, it is not without limitations. The retrospective nature of the analysis and the potential for selection bias in the surgical approach must be acknowledged. Furthermore, patient data at 6 months are only available for 506 patients, the others having been lost to follow-up. Prospective randomized studies would provide more robust evidence to guide clinical practice.

Conclusion

In conclusion, recurrence contribute to a poorer prognosis in CSDH. Nevertheless, use burr hole or minicraniotomy for the management of CSDH showed a similar recurrence rate and no significant differences in post-operative outcomes. This underlines the need for a thorough assessment of patients with CSHD and the importance of avoiding their occurrence, by promoting early mobilization of patients. Future research is necessary to mitigate the risk of recurrence, regardless of the surgical technique employed. These results do not encourage the prescription of corticosteroids, which have been shown in the literature to be associated with medical complications.

Data availability

We support data sharing within the restrictions of the ethical approval permissions. Reasonable requests can be made to the corresponding author.

References

Abecassis IJ, Kim LJ (2017) Craniotomy for treatment of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Clin N Am 28:229–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2016.11.005

Almenawer SA, Farrokhyar F, Hong C, Alhazzani W, Manoranjan B, Yarascavitch B, Arjmand P, Baronia B, Reddy K, Murty N, Singh S (2014) Chronic subdural hematoma management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34,829 patients. Ann Surg 259:449–457. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000255

Amano T, Miyamatsu Y, Otsuji R, Nakamizo A (2021) Efficacy of endoscopic treatment for chronic subdural hematoma surgery. J Clin Neurosci 92:78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2021.07.058

Aspegren OP, Åstrand R, Lundgren MI, Romner B (2013) Anticoagulation therapy a risk factor for the development of chronic subdural hematoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 115:981–984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.10.008

Chen JC, Levy ML (2000) Causes, epidemiology, and risk factors of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Clin N Am 11:399–406

Ducruet AF, Grobelny BT, Zacharia BE, Hickman ZL, DeRosa PL, Andersen KN, Sussman E, Carpenter A, Connolly ES (2012) The surgical management of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Rev 35:155–169 discussion 169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-011-0349-y

Duerinck J, Van Der Veken J, Schuind S, Van Calenbergh F, van Loon J, Du Four S, Debacker S, Costa E, Raftopoulos C, De Witte O, Cools W, Buyl R, Van Velthoven V, D’Haens J, Bruneau M (2022) Randomized trial comparing Burr Hole Craniostomy, Minicraniotomy, and twist Drill craniostomy for treatment of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurgery 91:304–311. https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000001997

Edlmann E, Giorgi-Coll S, Whitfield PC, Carpenter KLH, Hutchinson PJ (2017) Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy. J Neuroinflammation 14:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-017-0881-y

Feghali J, Yang W, Huang J (2020) Updates in chronic subdural hematoma: epidemiology, etiology, Pathogenesis, treatment, and Outcome. World Neurosurg 141:339–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.06.140

Gonugunta V, Buxton N (2001) Warfarin and chronic subdural haematomas. Br J Neurosurg 15:514–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688690120097822

Haseeb A, Shafique MA, Kumar A, Raqib MA, Mughal ZUN, Nasir R, Sinaan Ali SM, Ahmad TKF, Mustafa MS (2023) Efficacy and safety of steroids for chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Neurol Int 14:449. https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_771_2023

Hutchinson PJ, Edlmann E, Bulters D, Zolnourian A, Holton P, Suttner N, Agyemang K, Thomson S, Anderson IA, Al-Tamimi YZ, Henderson D, Whitfield PC, Gherle M, Brennan PM, Allison A, Thelin EP, Tarantino S, Pantaleo B, Caldwell K, Davis-Wilkie C, Mee H, Warburton EA, Barton G, Chari A, Marcus HJ, King AT, Belli A, Myint PK, Wilkinson I, Santarius T, Turner C, Bond S, Kolias AG (2020) Trial of Dexamethasone for Chronic Subdural Hematoma. N Engl J Med 383:2616–2627. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2020473. British Neurosurgical Trainee Research Collaborative, Dex-CSDH Trial Collaborators

Ivamoto HS, Lemos HP, Atallah AN (2016) Surgical treatments for chronic subdural hematomas: a comprehensive systematic review. World Neurosurg 86:399–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.025

Kinoshita S, Ohkuma H, Fujiwara N, Katayama K, Naraoka M, Shimamura N, Tabata H, Takemura A, Hasegawa S, Saito A (2024) Long-term postoperative prognosis and associated risk factors of chronic subdural hematoma in the elderly. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 108186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2024.108186

Kolias AG, Chari A, Santarius T, Hutchinson PJ (2014) Chronic subdural haematoma: modern management and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Neurol 10:570–578. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.163

Kurabe S, Ozawa T, Watanabe T, Aiba T (2010) Efficacy and safety of postoperative early mobilization for chronic subdural hematoma in elderly patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 152:1171–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0627-4

Lega BC, Danish SF, Malhotra NR, Sonnad SS, Stein SC (2010) Choosing the best operation for chronic subdural hematoma: a decision analysis. J Neurosurg 113:615–621. https://doi.org/10.3171/2009.9.JNS08825

Liu W, Bakker NA, Groen RJM (2014) Chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical procedures. J Neurosurg 121:665–673. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.5.JNS132715

Maldaner N, Sosnova M, Sarnthein J, Bozinov O, Regli L, Stienen MN (2018) Burr hole trepanation for chronic subdural hematomas: is surgical education safe? Acta Neurochir (Wien) 160:901–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3458-8

Mehta V, Harward SC, Sankey EW, Nayar G, Codd PJ (2018) Evidence based diagnosis and management of chronic subdural hematoma: a review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci 50:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.01.050

Nakajima H, Yasui T, Nishikawa M, Kishi H, Kan M (2002) The role of postoperative patient posture in the recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma: a prospective randomized trial. Surg Neurol 58:385–387 discussion 387. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00921-7

Santarius T, Kirkpatrick PJ, Kolias AG, Hutchinson PJ (2010) Working toward rational and evidence-based treatment of chronic subdural hematoma. Clin Neurosurg 57:112–122

Schucht P, Fischer U, Fung C, Bernasconi C, Fichtner J, Vulcu S, Schöni D, Nowacki A, Wanderer S, Eisenring C, Krähenbühl AK, Mattle HP, Arnold M, Söll N, Tochtermann L, Z’Graggen W, Jünger ST, Gralla J, Mordasini P, Dahlweid FM, Raabe A, Beck J (2019) Follow-up computed tomography after evacuation of chronic subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med 380:1186–1187. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1812507

Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Sedhai YR, Jain S, Karki P, Jha P, Mainali G, Ghimire P (2022) Steroid in chronic subdural hematoma: an updated systematic review and Meta-analysis Post DEX-CSDH Trial. World Neurosurg 158:84–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.10.167

Tazreean R, Nelson G, Twomey R (2022) Early mobilization in enhanced recovery after surgery pathways: current evidence and recent advancements. J Comp Eff Res 11:121–129. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2021-0258

Torihashi K, Sadamasa N, Yoshida K, Narumi O, Chin M, Yamagata S (2008) Independent predictors for recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma: a review of 343 consecutive surgical cases. Neurosurgery 63:1125–1129 discussion 1129. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000335782.60059.17

Weigel R, Schmiedek P, Krauss JK (2003) Outcome of contemporary surgery for chronic subdural haematoma: evidence based review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74:937–943. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.74.7.937

Wu L, Guo X, Ou Y, Yu X, Zhu B, Yang C, Liu W (2023) Efficacy analysis of neuroendoscopy-assisted burr-hole evacuation for chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev 46:98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02007-2

Yang W, Huang J (2017) Chronic subdural hematoma: epidemiology and natural history. Neurosurg Clin N Am 28:205–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2016.11.002

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SH, MS, TG and AL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SH and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study received the required authorization (CLERS 3339) from the institutional review board of our hospital. According to French legislation, the requirement for informed consent was waived for this observational retrospective study.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hounkpatin, S., Stierer, M., Frechon, P. et al. Comparative analysis of surgical techniques in the management of chronic subdural hematomas and risk factors for poor outcomes. Neurosurg Rev 47, 254 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-024-02493-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-024-02493-y