Abstract

Background

Bowel and/or mesentery injuries represent the third most common injury among patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Delayed diagnosis increases morbidity and mortality. The aim of our study was to evaluate the role of clinical signs along with CT findings as predictors of early surgical repair.

Material and methods

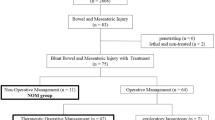

Between March 2014 and February 2017, charts and CT scans of consecutive patients treated for blunt abdominal trauma in two different trauma centers were reread by two experienced radiologists. We included all adult patients who underwent contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis with CT findings of blunt bowel and/or mesenteric injury (BBMI). We divided CT findings into two groups: the first included three highly specific CT signs and the second included six less specific CT signs indicated as “minor CT findings.” The presence of abdominal guarding and/or abdominal pain was considered as “clinical signs.” Reference standards included surgically proven BBMI and clinical follow-up. Association was evaluated by the chi-square test. A logistic regression model was used to estimate odds ratio (OR) and confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Thirty-four (4.1%) out of 831 patients who sustained blunt abdominal trauma had BBMI at CT. Twenty-one out of thirty-four patients (61.8%) underwent surgical repair; the remaining 13 were treated conservatively. Free fluid had a significant statistical association with surgery (p = 0.0044). The presence of three or more minor CT findings was statistically associated with surgery (OR = 8.1; 95% CI, 1.2–53.7). Abdominal guarding along with bowel wall discontinuity and extraluminal air had the highest positive predictive value (100 and 83.3%, respectively).

Conclusion

In patients without solid organ injury (SOI), the presence of free fluid along with abdominal guarding and three or more “minor CT findings” is a significant predictor of early surgical repair. The association of bowel wall discontinuity with extraluminal air warrants exploratory laparotomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Blunt bowel mesentery injuries (BBMI) are relatively rare. Current literature reports an incidence of 1–5% of BBMI, which represents the third most common injury among patients who sustained blunt abdominal trauma. Severe complications and high mortality rates may result if the diagnosis is not performed promptly [1].

CT is the gold standard in early evaluation of patients with BBMI [2], because it is fast and noninvasive and able to show both highly and less specific findings of BBMI. There are a few highly specific CT findings of BBMI (discontinuity of bowel wall, oral contrast leakage, extraluminal air, and active bleeding) that may predict the need of immediate laparotomy [3]. Conversely, less specific (minor) CT findings such as intramural air, focal bowel wall thickening, abnormal bowel wall enhancement, mesenteric fat stranding, and free fluid are more common and suggestive of BBMI, but do not predict the need for timely surgery. In such cases, therapeutic laparotomy could be delayed and the clinical outcome significantly impaired. Optimal management of hemodynamically stable patients with minor CT findings of BBMI remains unclear. Current literature supports the need for a reliable tool, which might be useful for surgeons to make an objective and timely decision for the management of hollow viscous and mesenteric injuries [4, 5].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the role of clinical signs, such as abdominal pain and guarding, along with CT findings as predictors of early surgical repair.

Patients and methods

This is a retrospective data collection at two major urban trauma centers, using the institutions’ trauma registry. The institutional review board of both hospitals approved the study. Informed patient consent was waived.

We included all consecutive adult blunt trauma patients (age > 16 years) admitted to Cà Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital, Milan, Italy, and Pope John XXIII Hospital, Bergamo, Italy, between March 2014 and February 2017, who underwent a focused abdomen and pelvis CT scan or in a context of whole-body CT for trauma, with CT findings suspicious for BBMI. All patients were administered a biphasic power injection of a nonionic IV contrast agent (Iopamiro®, Bracco) through an antecubital vein of 1.3 mL/kg of patient body weight at a 370 mg/mL iodine concentration and a flow of 2.5/3 mL/s followed by a saline chaser bolus of 50 mL. The dual-phase CT abdomen and pelvis protocol included the acquisition of an arterial and portal venous phase using a 128-multi-detector CT (MDCT) scanner (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare) and a 64-MDCT scanner (LightSpeed General Electric, USA) No oral contrast agent was administered.

The diagnosis of multiple traumas was made in cases with an Injury Severity Score (ISS) greater than 16, either suspected by emergency physicians on the scene or by early survey at the trauma bay. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) hemodynamic instability, (2) no BBMI described either in the electronic chart system or the radiology report, (3) associated solid organ injuries (SOI), (4) withholding CT scan for urgent laparotomy, (5) patients who were not assessable during physical examination (e.g., intubated and unconscious patients), and (6) patients who underwent more than one CT scan for follow-up purposes. Data collection included patient demographics, injury mechanism, physiologic conditions at admission, health status before and after surgery, and clinical course during critical care. Two board-certified consultant radiologists (MCF, FS) with more than 10 years of experience in CT relevant to the trauma setting independently reviewed all archived digital CT scans in a blind fashion by using Synapse (Fujifilm, Japan) or Carestream-Vue (USA) picture archiving and communication system (PACS) workstations. In case of discordance, consensus was obtained by a third board-certified radiologist (AAL) with 18 years of experience in emergency radiology. The presence of abdominal guarding and/or abdominal pain, retrieved from the electronic chart system, was considered as “clinical signs.” We divided CT signs into two groups: the first included three highly specific BBMI CT findings (bowel wall discontinuity, active bleeding, and extraluminal air) and the second group included six less specific BBMI CT findings (intramural air, bowel wall thickening, abnormal bowel, wall enhancement, mesenteric stranding, and free fluid), indicated as “minor CT findings” (Tables 1 and 2). Reference standards comprised surgically proven BBMI and clinical follow-up until day 30 after the accident. Participants were followed up as outpatients conjointly by general practitioners and ambulatory surgeons.

Statistical analysis

We described the frequency of all variables according to the presence or absence of surgical repair. Association was assessed by the chi-square test. For multiple comparisons, a new threshold for alpha according to the Šidák correction was calculated [6]. Assuming m as the number of tests considered and a familywise α of 0.05, each null hypothesis with a p value lower than 1 − (1 − α)1/m was rejected. For clinical signs and CT findings, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and Youden’s index as a function of surgery. Youden’s index [7] (which is equal to sensitivity + specificity − 1) provides a value between 0 and 1 and represents the ability to predict surgery. A Youden’s index next to 1 means very high sensitivity and specificity, while a value close to 0 represents poor sensitivity and specificity. The predictive values of each clinical sign and CT findings were also evaluated.

Finally, a logistic regression model was used to estimate the odds ratio. “Surgery YES/NO” was used as a dependent variable, whereas as independent variables, we used “abdominal pain” and “abdominal guarding,” which were grouped as follows: NO = neither of the two clinical signs; YES = at least one clinical sign, “active bleeding,” “bowel wall discontinuity and extraluminal air,” “and minor CT findings” (Table 2).

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical package version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA, 2009).

Results

Thirty-four (4.1%) out of 831 patients (31 males, 3 females; range 18–84 years, median age 41.3 years,) had CT findings consistent with BBMI. Twenty-one out of 34 patients (61.8%) underwent surgical repair. The remaining 13 patients were treated conservatively with good outcome. Overall, 21/34 patients had surgically proven BBMI. There were no discordant cases between the two readers who independently reviewed all archived digital CT scans.

Table 1 shows the frequency of the different variables depending on whether or not patients had surgery. The only variable with a significant statistical association with surgery was “minor CT findings” (≥ 3 vs <3 ): OR = 8.1 (95% CI: 1.2–53).

The most common mechanism of injury associated with surgery was vehicle crash. The presence of “abdominal guarding” symptom and “bowel wall discontinuity” sign at CT was followed by surgical repair in all cases. Only two thirds of the patients with “abdominal pain” or “active bleeding” at CT underwent surgical repair. The variable with the highest Youden’s Index was “minor CT findings” (Table 2).

Free fluid (FF) had a significant statistical association with surgery (p = 0.0044, Table 1). Abdominal guarding along with bowel wall discontinuity, extraluminal air, and minor CT findings had the highest positive predictive value (PPV), whereas sensitivity values were relatively low (Table 2). Two patients had minor active bleeding treated conservatively (Fig.1), whereas in one patient, active bleeding was missed in the original report. Ten patients (83%) with extraluminal air underwent surgical repair, whereas two patients (17%) were treated conservatively with positive outcome. There were no false positive for BBMI resulting in negative exploratory laparotomies.

A 48-year-old man after blunt abdominal trauma. Axial arterial (a) and venous (b) contrast-enhanced CT scan showing a small spot of contrast agent (arrows) along with mesentery stranding, increasing in the portal venous phase, in keeping with active bleeding. The patient was treated conservatively with positive outcome

Discussion

Delayed diagnosis of BBMI results in increased morbidity and mortality, usually because of hemorrhage or peritonitis. Physical examination alone may not be highly accurate to diagnose BBMI. Abdominal pain and/or abdominal guarding are important clinical signs but their presence does not necessarily indicate the need for timely laparotomy. In addition, these clinical signs might not be present in the initial clinical assessment. Furthermore, if the patient had concomitant head and/or spinal cord trauma, abdominal assessment may be difficult. Associated injuries, intoxication with alcohol, or other substances as well as the administration of medications for pain or agitation may significantly affect the reliability of physical examination [8].

A substantial body of literature is based on the assumption that physical examination alone is an insensitive predictor of BBMI [9,9,11] and does not correlate clinically with bowel injury in the setting of blunt trauma [12, 13]. A multi-institutional study identified abdominal guarding more commonly in perforated than in non-perforated small-bowel injury [8]. The authors found that all patients with abdominal pain and/or guarding had BBMI requiring surgical repair. This outcome did not differ significantly from our results. On the other hand, 92% of the patients without abdominal pain were also found to have BBMI during exploratory laparotomy. McNutt MK et al. [4] demonstrated that abdominal guarding was present in 72% of the patients and was considered as a significant predictor of blunt hollow viscous injury. Conversely, 24% of the patients with BBMI did not have abdominal guarding. The use of clinical assessment as the sole predictor for surgery produced negative laparotomy rates as high as 40% [14]. It is interesting to note that CT findings along with clinical signs did not produce any negative laparotomy result in our study, supporting the high negative predictive value of CT [12].

The use of CT or physical examination alone has been shown to be suboptimal in the diagnosis of BBMI [12, 15]. Several articles in the literature described radiographic features of BBMI, but only a few studies combined CT findings and clinical signs to predict the need of surgical repair [4]. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies assessing the role of clinical signs along with CT findings in blunt trauma patients suspected of having BBMI. In our series, free fluid (FF) had a significant statistical association with surgery (p = 0.0044). This result is discordant if compared to the current literature in which intra-peritoneal FF is considered a concerning finding in the setting of blunt abdominal trauma, with a sensitivity and specificity of 90–100% and 15–25%, respectively [5, 16, 17]. However, high-attenuation fluid in the absence of SOI may indicate hemoperitoneum and raise the suspicion of BBMI.

Interestingly, in our sample, the significant statistical association of FF with surgery in the absence of SOI is supported by the significant statistical association with surgery and associated “minor CT findings” in the same patient. In particular, when three or more of these findings are detected in a patient without SOI, BBMI must be suspected.

Each remaining minor CT finding, studied individually, had no significant statistical association with surgery. However, some CT findings such as bowel wall thickening and abnormal bowel wall enhancement (Fig. 2) were present in a high percentage of patients who had surgically proven BBMI (Table 1). Focal, isolated, and unequivocal bowel wall thickening measuring up to 3–4 mm is an important indirect sign of bowel contusion, whereas diffuse bowel wall thickening is atypical for contusion. When diffuse small-bowel wall thickening of more than 10 mm is seen, it should be considered a sign of shock bowel, either with or without associated hypoperfusion complex [18, 19]. Abnormal contrast wall enhancement from bowel injury is uncommon and may be seen as a short segments of increased patchy and irregular enhancement suggestive, but not diagnostic, of full-thickness injury [20, 21]. Increased focal mucosal contrast enhancement of the small-bowel wall can be seen in bowel ischemia, particularly after reperfusion from an arterial injury [22]. Abnormally increased contrast enhancement may also be seen in shock bowel, where local vascular damage from hypovolemic shock results in interstitial leakage of contrast material [23].

A 35-year-old man after blunt abdominal trauma due to motorbike accident. a Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows wall thickening of the distal ileum associated with abnormal small-bowel wall contrast enhancement (arrowhead). There is also evidence of a high-attenuation fluid collection in the right iliac fossa consistent with hemoperitoneum (black arrow). b Coronal multi-planar reconstruction shows multiple air bubbles in the right iliac fossa and epigastrium (white arrows), secondary to small-bowel wall laceration. c Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows peri-aortic mediastinal hematoma and hemotorax as additional findings

According to the current literature, our results demonstrated that all patients with abdominal guarding at clinical evaluation and with bowel wall discontinuity at CT had surgically proven BBMI (Table 1). Bowel wall discontinuity and abdominal guarding had high specificity and low sensitivity, respectively. In addition, bowel wall discontinuity was seen in only 5/34 of the patients. This small number of cases can be explained by the small size of the discontinuities and/or the lack of oral contrast agent administration in our sample. Although a debate about conservative treatment of active bleeding (Figs. 1–3) has recently emerged [24, 25], in our study, three out of ten patients with active bleeding were treated conservatively and had positive outcome. In regard to free air, our results did not differ significantly from the current literature. In spite of the high specificity, free air is not pathognomonic of bowel perforation and can be seen in several iatrogenic and non-iatrogenic conditions, such as Foley catheter placement in patients with intra-peritoneal bladder rupture [5, 26,24,25,29]. In our study, the association of bowel wall discontinuity with extraluminal air showed high specificity and high positive predictive value of BBMI and warranted exploratory laparotomy in all cases (Table 2).

The limitation of our study is related to the small sample size, which reflects the low incidence of BBMI among patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Second, data accuracy is subject to documentation errors in the medical chart record and trauma registry.

Third, one might argue that the surgeon (SM), who had already reviewed medical chart records and CT images, should not have been involved in the patients’ recruitment. We accepted this possible methodological weakness for logistic and practical reasons. Recall bias, which is unlikely because of the large volume of data randomly matched between the two hospitals, may influence indices of sensitivity and specificity but it is of minor importance as far as there were no discordant cases between the two readers who independently reviewed all archived digital CT scans.

Fourth, potential selection bias may influence indices of sensitivity and specificity as well. Nonetheless, the large volume of patients randomly matched between the two hospitals may minimize selection bias.

Finally, the design was still susceptible to partial verification bias; since only positive clinical signs and CT findings or later clinical symptoms led to surgical repair, there might be an unknown prevalence of minor sub-clinical BBMI missed.

In conclusion, in patients without SOI, the presence of free fluid along with abdominal guarding and three or more “minor CT findings” is a significant predictor of early surgical repair. The association of bowel wall discontinuity with extraluminal air warrants exploratory laparotomy.

References

Scaglione M, De Lutio di Castelguidone E, Scialpi M et al (2004) Blunt trauma to the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery: is there a role for helical CT in the decision-making process? Eur J Radiol 50:67–73

Cinquantini F, Tugnoli G, Piccinini A, Coniglio C, Mannone S, Biscardi A, Gordini G, di Saverio S (2017) Educational review of predictive value and findings of computed tomography scan in diagnosing bowel and mesenteric injuries after blunt trauma: correlation with trauma surgery findings in 163 patients. Can Assoc Radiol J 68:276–285

Brody JM, Leighton DB, Murphy BL, Abbott GF, Vaccaro JP, Jagminas L, Cioffi WG (2000) CT of blunt trauma bowel and mesenteric injury: typical findings and pitfalls in diagnosis. Radiographics 20:1525–1527

McNutt MK, Chinapuvvula NR, Beckmann NM et al (2015) Early surgical intervention for blunt bowel injury: the Bowel Injury Prediction Score (BIPS). J Trauma Acute Care Surg 78:105–111

Bates DDB, Wasserman M, Malek A, Gorantla V, Anderson SW, Soto JA, LeBedis CA (2017) Multidetector CT of surgically proven blunt bowel and mesenteric injury. Radiographics 37:613–625

Abdi H (2007) The Bonferonni and Šidák corrections for multiple comparisons. In: Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Youden W (1950) Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 3:32–35

Joseph DK, Kunac A, Kinler RL et al (2013) Diagnosing blunt hollow viscus injury: is computed tomography the answer? Am J Surg 205:414–418

Yu J, Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Cockrell C, Halvorsen RA (2011) Blunt bowel and mesenteric injury: MDCT diagnosis. Abdom Imaging 36:50–61

Malinoski DJ, Patel MS, Yakar DO, Green D, Qureshi F, Inaba K, Brown CVR, Salim A (2010) A diagnostic delay of 5 hours increases the risk of death after blunt hollow viscus injury. J Trauma 69:84–87

Fakhry SM, Brownstein M, Watts DD et al (2000) Relatively short diagnostic delays (< 8 hours) produce morbidity and mortality in blunt small bowel injury: an analysis of time to operative intervention in 198 patients from a multicenter experience. J Trauma 48:408–14–5

Livingston DH, Lavery RF, Passannante MR et al (1998) Admission or observation is not necessary after a negative abdominal computed tomographic scan in patients with suspected blunt abdominal trauma: results of a prospective, multi-institutional trial. J Trauma 44:273–80–2

Dowe MF, Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, Steiner RC, Cooper C (1997) CT findings of mesenteric injury after blunt trauma: implications for surgical intervention. AJR Am J Roentgenol 168:425–428

Brofman N, Atri M, Hanson JM, Grinblat L, Chughtai T, Brenneman F (2006) Evaluation of bowel and mesenteric blunt trauma with multidetector CT. Radiographics 26:1119–1131

Ekeh AP, Saxe J, Walusimbi M, Tchorz KM, Woods RJ, Anderson HL III, McCarthy MC (2008) Diagnosis of blunt intestinal and mesenteric injury in the era of multidetector CT technology—are results better? J Trauma 65:354–359

Soto JA, Anderson SW (2012) Multidetector CT of blunt abdominal trauma. Radiology 265:678–693

Drasin TE, Anderson SW, Asandra A, Rhea JT, Soto JA (2008) MDCT evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma: clinical significance of free intraperitoneal fluid in males with absence of identifiable injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191:1821–1826

Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K, Erb R (1994) Diffuse small-bowel ischemia in hypotensive adults after blunt trauma (shock bowel): CT findings and clinical significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 163:1375–1379

Prasad KR, Kumar A, Gamanagatti S, Chandrashekhara SH (2011) CT in post-traumatic hypoperfusion complex—a pictorial review. Emerg Radiol 18:139–143

Virmani V, George U, MacDonald B, Sheikh A (2013) Small-bowel and mesenteric injuries in blunt trauma of the abdomen. Can Assoc Radiol J 64:140–147

Malhotra AK, Fabian TC, Katsis SB, Gavant ML, Croce MA (2000) Blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries: the role of screening computed tomography. J Trauma 48:991–1000

Dhatt HS, Behr SC, Miracle A, Wang ZJ, Yeh BM (2015) Radiological evaluation of bowel ischemia. Radiol Clin N Am 53:1241–1254

Ames JT, Federle MP (2009) CT hypotension complex (shock bowel) is not always due to traumatic hypovolemic shock. AJR Am J Roentgenol 192:W230–W235

Alarhayem AQ, Myers JG, Dent D et al (2015) Blush at first sight significance of computed tomographic and angiographic discrepancy in patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Surg 210:1104–10–1

Ingram M-CE, Siddharthan RV, Morris AD, Hill SJ, Travers CD, McKracken CE, Heiss KF, Raval MV, Santore MT (2016) Hepatic and splenic blush on computed tomography in children following blunt abdominal trauma: is intervention necessary? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 81:266–270

Marek AP, Deisler RF, Sutherland JB, Punjabi G, Portillo A, Krook J, Richardson CJ, Nygaard RM, Ney AL (2014) CT scan-detected pneumoperitoneum: an unreliable predictor of intra-abdominal injury in blunt trauma. Injury 45:116–121

Hamilton P, Rizoli S, McLellan B, Murphy J (1995) Significance of intra-abdominal extraluminal air detected by CT scan in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 39:331–333

Izumi J, Hirano H, Kato T, Ito T, Kinoshita K, Wakabayashi T (2012) CT findings of spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of the urinary bladder: two case reports. Jpn J Radiol 30:284–287

Hanks PW, Brody JM (2003) Blunt injury to mesentery and small bowel: CT evaluation. Radiol Clin North Am 41:1171–1182

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Firetto, M.C., Sala, F., Petrini, M. et al. Blunt bowel and mesenteric trauma: role of clinical signs along with CT findings in patients’ management. Emerg Radiol 25, 461–467 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-018-1608-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-018-1608-9