Abstract

Planning for the future requires a detailed understanding of how climate change affects a wide range of systems at spatial scales that are relevant to humans. Understanding of climate change impacts can be gained from observational and reconstruction approaches and from numerical models that apply existing knowledge to climate change scenarios. Although modeling approaches are prominent in climate change assessments, observations and reconstructions provide insights that cannot be derived from simulations alone, especially at local to regional scales where climate adaptation policies are implemented. Here, we review the wealth of understanding that emerged from observations and reconstructions of ongoing and past climate change impacts in Switzerland, with wider applicability in Europe. We draw examples from hydrological, alpine, forest, and agricultural systems, which are of paramount societal importance, and are projected to undergo important changes by the end of this century. For each system, we review existing model-based projections, present what is known from observations, and discuss how empirical evidence may help improve future projections. A particular focus is given to better understanding thresholds, tipping points and feedbacks that may operate on different time scales. Observational approaches provide the grounding in evidence that is needed to develop local to regional climate adaptation strategies. Our review demonstrates that observational approaches should ideally have a synergistic relationship with modeling in identifying inconsistencies in projections as well as avenues for improvement. They are critical for uncovering unexpected relationships between climate and agricultural, natural, and hydrological systems that will be important to society in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Climate change is altering human and natural systems in many regions of the world, and climate change impacts are likely to intensify during the twenty-first century (Parmesan and Yohe 2003; IPCC 2014). Whereas greenhouse forcing of the climate system is a global-scale process that requires multinational cooperation to address, the impacts of global climate change on human and natural systems are felt at local to regional scales (Brönnimann et al. 2014; Hewitson et al. 2014). Changing temperature and precipitation regimes may enhance or diminish plant growth and agricultural productivity depending on the regional climatic setting (Lindner et al. 2010; Bindi and Olesen 2011). Likewise, hydrological regimes that constrain water supplies and flood hazards vary depending on regional changes in evaporation and the seasonality and abundance of precipitation (Lehner et al. 2006). Consequently, developing policies to maintain productivity, sustainability, and diversity, and thereby safeguard prosperity in an era of rapidly changing climate, requires region-specific understanding of how climate change impacts human and natural systems.

The research strategies used to develop local and regional understanding of climate change impacts can be broadly separated into observational and modeling approaches. On a primary level, observations (including experiments, instrumental measurements, reconstructions from natural archives, and documentary evidence) provide the baseline data needed to understand human and natural systems, identify changes and trends, and ultimately attribute impacts to climatic or other external drivers (Rosenzweig and Neofotis 2013). In turn, modeling approaches (e.g., process-based or statistical impact models) can apply empirical understanding of system function gained from observations to project climate change impacts in the future (IPCC 2014). Increasingly sophisticated impact models apply regional climate projections to simulate climate change impacts on agricultural and forest productivity, biodiversity, snow and glaciers, water supplies, and human health (CH2014-Impacts 2014; Kovats et al. 2014). Such regional projections of future impacts are critical for developing long-term adaptation strategies. However, observational data also have direct value for anticipating the impacts of projected climatic changes, and are needed to build an empirically grounded foundation for understanding impacts at multiple spatial and temporal scales given that observations provide mechanistic understanding of impacts on system components (e.g., drought stress on individual plant species) and key vulnerabilities (e.g., catchment flood probabilities in warm and cool climates). Furthermore, modeling and observational approaches ideally have a synergistic relationship, with observations identifying consistencies with and omissions from model projections and thereby providing information not attainable from models alone.

In this paper, we discuss how observational approaches inform climate change impact projections for hydrological systems, alpine meadows, forests and agriculture in Switzerland. These systems are of paramount societal importance, and in the case of Alpine ecosystems have unique ecological and cultural significance in Switzerland. Furthermore, our review ranges from low-human impact (e.g., alpine meadows) to human-dominated (e.g., agriculture) ecosystems. Switzerland encompasses several major biomes of Europe, from mild sub-Mediterranean to harsh arctic-alpine conditions. Thus, we present climate change impacts on a spectrum of natural and human systems in a climatically diverse region with wider applicability in Europe, and the mountain regions of the world. We apply a broad definition of observational approaches by considering all techniques that produce empirical datasets (Fig. 1). Such approaches cover a wide temporal range, from millennial to centennial climate impact reconstructions using sedimentary archives, to the sub-annual to decadal resolution of dendroecology and historical records, as well as precise instrumental measurements, and experiments. We first present projections of how each important system will be impacted by climate change. We then discuss what is known about how climate change impacted the system in the past or in experimental settings, and how these impacts were critical to society or to ecosystems. We also examine what aspects of climate drove the changes by considering whether changes were linear with a climatic variable, or if extreme events, tipping points, and feedbacks drove the observed changes. A key focus is how different time scales and approaches provide additional insights. We conclude with observation-based recommendations that arise from our review.

(1) Examples of empirical climate change impact data drawn from multiple systems for this study (at different temporal scales) range from (a) controlled laboratory studies (scale of days to years) including physiological measurements and greenhouse experiments; (b) field measurements and experiments (scale of days to years) including transect studies, physiological measurements in the field, and drought treatments; (c) time series of instrumental measurements (scale of years to decades) are gained from observed changes in the albedo of glaciers, crop yields, monitoring plots, phenological records, and streamflow gages; (d) proxies from cultural archives (scale of years to millennia) include written sources and archeological investigations; (e) proxies from natural archives (scale of years to millennia) are gained from e.g. tree rings, glacier ice, and lake sediments. Empirical data may be (2) directly applied to understand system processes and to identify, attribute, and anticipate the consequences of climate change. (3) Empirical climate change impact studies should also have a synergistic relationship with climate impact models in (a) the development of climate impact assessments through the application of theory gained from observational approaches; (b) the identification of inconsistencies in, and omissions from, model-based projections; and (c) for identifying adaptation strategies that are supported by empirical data

Projected climate change impacts on key systems in Switzerland

Simulations suggest that mean annual temperatures in Switzerland will likely increase by 3–5 °C by 2085 AD, with the highest rate of change after 2050 AD (CH2011 2011). Projected temperatures increase throughout Switzerland in all seasons, with the strongest warming south of the Alps during summer. Whereas extreme summer heat events similar to the heat wave of 2003 are likely to be more frequent and intense, extreme cold events will be less likely, and the frequency of winter warm spells will increase. Precipitation projections for Switzerland include considerable uncertainty (CH2011 2011). Regional climate models project increases in annual precipitation for northern Europe, and a decrease in southern Europe. Because Switzerland and the Alps lie in the transition between these regions, precipitation could either increase or decrease. Winter precipitation will likely increase south of the Alps, but outcomes are highly uncertain for other regions (CH2011 2011). However, a mean decrease in precipitation is likely throughout Switzerland during summer when the transition between northern European and Mediterranean climate regimes shifts northward.

Modeling outcomes suggest that temperature increases will have important ecological and societal impacts in Switzerland (CH2014-Impacts 2014). For example, a 4 °C increase in mean annual temperature is equivalent to a theoretical 700 m upward shift of the alpine treeline (Theurillat and Guisan 2001). Recent studies that combined downscaled climate scenarios and process-based crop models projected negative impacts of climate change on the mean and stability of major crop yields in Switzerland by 2050 and beyond, when assuming current crop and farm management characteristics (Torriani et al. 2007a, b). Adaptive measures may mitigate impacts of increasing temperatures and declining precipitation (Klein et al. 2014), but given the uncertainty of both climate projections and crop models (Holzkämper et al. 2015), it is essential to place such projections in context with past observed yield trends to identify the most effective and robust adaptation strategies.

The combined impacts of changing temperature and precipitation on ecosystems in Switzerland will vary regionally. Declining productivity is projected for warm, dry sites in rain-sheltered valleys of the Central Alps, such as Central Valais, where precipitation abundance limits productivity at present (Huber et al. 2013; Elkin et al. 2015). In contrast, rising temperatures should increase productivity in temperature-limited montane forests where precipitation is abundant (Elkin et al. 2013). Although warmer growing seasons may also favor tree growth on the Swiss Plateau, increasing drought associated with warmer summers could limit the distributions of the two most abundant and economically important tree species, Picea abies (spruce), and Fagus sylvatica (beech; Weber et al. 2013; Lévesque et al. 2014a). Disturbance regimes that drive forest dynamics are also projected to change, with increases in fire risk in the Southern and Central Alps where fires occur at present, and the possible development of fire risk in moister habitats such as the Swiss Plateau (Pezzatti et al. 2016). Rising temperatures may also expose new regions to insect outbreaks and increase forest mortality by allowing more generations of insect pests (Johnson et al. 2010; Bugmann et al. 2014).

Increasing temperatures and decreasing summer precipitation would alter runoff generation in Switzerland, with important consequences for water resources, infrastructure, and aquatic ecosystems (Köplin et al. 2014). Recent projections of mean runoff show increasing winter discharge, decreasing summer discharge and earlier snowmelt, but little change in total volume of runoff (Addor et al. 2014; Rössler et al. 2014). Projected losses of 90% of glacier mass by 2100 (Marty et al. 2014), and a decreasing proportion of precipitation falling as snow (Schmucki et al. 2015) are crucial processes contributing to expected changes in mean flow. Anticipating climate change impacts on high flows, low flows, and flood frequencies is more difficult. Whereas floods mainly depend on the magnitude of precipitation events, low flows depend on the frequency of precipitation. Climate model ensembles project increased precipitation intensity, but decreasing precipitation days in summer (Fischer et al. 2015), and therefore an increase in hydrological extremes. However, overall uncertainties in projecting precipitation are much larger than for temperature, and model projections have yet to reach consensus with historical and instrumental flood records (Christensen and Christensen 2003; Mudelsee et al. 2003; FOEN 2012; Amann et al. 2015). Therefore, long-term data sets that resolve this relationship are needed to improve projections for heavy precipitation and floods.

Observed hydrological changes

Climate change impacts on water, snow, and ice in Switzerland

Historical streamflow records can link runoff generation to changing climate. In Switzerland, discharge data from the River Rhine at Basel (mean discharge, low flows, and floods) for the last 200 years record the hydrological responses to climatic variables of the entire region north of the Alps (36,000 km2), and are consistent with overall regional changes in discharge. Although annual precipitation had an increasing trend (+1.05 mm/year), during the last 200 years, there was no clear trend in annual runoff (i.e., only +0.07 mm/year). Instead, and in agreement with future projections, runoff was more affected by temperature than by changes in precipitation; rising temperatures during the twentieth century increased evapotranspiration (+1.2 mm/year), and compensated for precipitation increases (Schädler and Weingartner 2010; Blanc and Schädler 2014). Increasing temperatures and precipitation also caused a shift in the seasonal distribution of runoff to higher values during spring, autumn, and especially winter. However, the year-to-year-variability of runoff is not a function of temperature but precipitation abundance during winter and spring (Hänggi and Weingartner 2011).

The trend to higher discharge during winter and spring in Switzerland is consistent with many catchments in Europe (Stahl et al. 2010), and is linked to a temperature increase that caused a shift from snow to rain and enhanced snowmelt (Birsan et al. 2005; Hänggi and Weingartner 2011). This effect is also evident at the mesoscale and on a shorter time scale. An analysis of runoff from 48 catchments covering different hydrological regime types in Switzerland since the 1960s found that annual runoff increased due to positive trends in winter, spring, and autumn, but found no clear trend in summer (Birsan et al. 2005). These changes in runoff are correlated to temperature changes, especially the number of days above 0 °C, whereas precipitation shows no clear signal. This indicates a balancing of evapotranspiration loss, precipitation changes, and glacier loss also at the mesoscale. A significant increase in discharge during low flows at Basel can also be partially attributed to climatic changes. Whereas increased low flows after 1900 AD resulted from rising winter temperatures, a second increase after 1950 AD relates both to a changing climate and to an increasing contribution from hydropower plants (Weingartner and Pfister 2007).

Complex responses of the hydrological system to climate change

The impacts of climate change on flood frequencies are of critical importance to society. Floods were frequent during most of the twentieth century except for the mid-century (1940–1970) “flood gap” (Wetter et al. 2011). Although a distinct rise in flood occurrence followed 1970, this rise is within the natural variability, and prominent only because it followed a period of infrequent floods. Nevertheless, increasing flood occurrence after 1970 led to an increase of the flood protection level and hence flood protection costs. Historical records from 14 Swiss catchments demonstrate that flood frequency fluctuated during the last 500 years (Schmocker-Fackel and Naef 2012). Four periods characterized by frequent flood occurrence are intersected by periods with few floods. Although flood occurrence seems to correlate with atmospheric conditions, no correlation with temperature, solar activity, or climatic indices (e.g., North Atlantic Oscillation) has been found on the centennial scale (Schmocker-Fackel and Naef 2012). Thus, longer term records are needed to resolve relationships between flood regimes and climatic conditions in general, and temperature changes in particular.

Annually laminated (varved) sediments from Lake Silvaplana (eastern Swiss Alps) with absolute warm-season temperature information reconstructed using chironomids and biogenic Si, and intercalated flood layers, provide information for the relationship between flood frequency and mean summer temperature during past intervals that were cooler or warmer than today. Flood event layers in the Alps were more frequent during cool and/or wet phases in the period 1450 BC to AD 420 (Stewart et al. 2011), but also during the last millennium and the late Holocene (Glur et al. 2013; Amann et al. 2015). Detailed quantitative analysis of the negative relationship between summer temperature and flood frequency (r = −0.86, p corr < 0.01; Stewart et al. 2011) revealed that the increase in flood frequency with cooler summer temperatures was not linear. Moreover, in periods with warmer summers than 1950–2000 values (i.e., analogues for twenty-first century warming), floods were less frequent than the mean between ca. 1450 BC and AD 420.

Observed changes in alpine meadows

Climate change impacts on alpine meadows

Under natural conditions, plant species distributions are mainly determined by climate. This is particularly true in alpine meadows, the most natural ecosystems in Switzerland (Burga 1988; Tinner and Theurillat 2003). Several long-term monitoring studies show that since the end of the Little Ice Age (LIA), new species have invaded the sparse vegetation of the upper alpine and subnival belts, and existing populations have become more abundant, especially in the eastern Swiss Alps (Grabherr et al. 1994; Walther et al. 2005; Wipf et al. 2013), with changes evident even at the decadal scale (Gottfried et al. 2012; Pauli et al. 2012). Observed trends correspond in part to recolonization and niche-filling since the LIA (Kammer et al. 2007), and to less intense land use during recent decades in the deforested upper subalpine belt (Bühlmann et al. 2014). However, vegetation shifts in response to recent warming are evident at the lower elevational limits of alpine meadows where forests and shrublands expanded (Bolli et al. 2007; Gehrig-Fasel et al. 2007).

Recent high-resolution sedimentary records suggest that before land use became important, treeline and subalpine vegetation were in dynamic equilibrium with climate. Juniperus shrublands and Betula woodlands expanded without measurable lag into the arctic-alpine steppe tundra of the Swiss Plateau 14,700 years ago, when summer temperatures increased by 3–4 °C (Lotter et al. 2012; Ammann et al. 2013; Heiri et al. 2015). A rapid rise of treeline by 800 m over 200–300 years is documented during the warming at the onset of the Holocene (+3–4 °C in 50–100 years; Tinner and Kaltenrieder 2005; Heiri et al. 2014). Thus, at these spatial (ca. 0–3 km radius) and temporal (decadal) scales, there is little vegetational inertia to climatic change, a hypothesis proposed before the availability of high-resolution time series comparing climatic and vegetational dynamics (Cole 1985).

Complex responses to climate change in alpine meadows

Alpine meadows are limited by a short growing season on the cold edges of their distributions, and by competition with taller plants at the warm edge (Guisan et al. 1998), where physiological limitations in acclimation to warmer temperatures also occur (Larigauderie and Körner 1995; Crawford 2008). Species distributions in alpine meadows are strongly determined by microtopographic variation, which constrains radiation, snow accumulation, and other physical factors. Microtopography can buffer an increase of mean air temperature up to 2 °C (Körner 2003; Scherrer and Körner 2011), which may explain the great stability (plant cover, number of species, floristic composition) in alpine Carex curvula meadows during the last decades as mean air temperature increased by more than 1 °C (Windmaisser and Reisch 2013), and also the persistence of endemics during the Holocene (Patsiou et al. 2014). However, combined paleoecological, paleoclimatic, and modeling evidence suggests a high temperature sensitivity of subalpine and alpine communities, which faithfully tracked climatic changes of >1–2 °C, at multi-decadal scales, with repeated reciprocal substitutions of subalpine forest and alpine meadow populations during the Holocene (Bugmann and Pfister 2000; Tinner and Theurillat 2003; Colombaroli et al. 2010; Schwörer et al. 2014a). This long-term evidence is in agreement with ecological assessments assuming a 1–2 °C threshold for resilience to warming for alpine ecosystems (Körner 1995; Theurillat et al. 1998; Theurillat and Guisan 2001).

Observed changes in forest ecosystems

Climate change impacts on forests in Switzerland

The most immediate climate change impacts on forests relate to plant phenology (e.g., timing of leaf emergence, flowering). The influence of warming projected for the end of the twenty-first century for Switzerland has been quantified for mountain forests using an altitudinal transect with an approximately 4 °C temperature gradient (Moser et al. 2010; King et al. 2013). Such an “elevation for time” approach enabled observation of the timing, duration, and rates of tree growth on multiple temporal scales. The warming projected for Switzerland by 2050 would lengthen the growing season of subalpine forests by 2–3 weeks. Impacts of temperature change on plant phenology are also evident in low-elevation ecosystems in time series developed from single species (Defila and Clot 2001), plant indices (Rutishauser and Studer 2007), and remotely sensed greening indices (Studer et al. 2007; Stöckli et al. 2011) that document a baseline of natural variability in plant phenology. During the last three centuries, spring phenological onset varied interannually by about 1 month. Most of the flowering and leaf-out dates after 1990 are earlier than the long-term average (27 April), and moving linear trend analysis shows an unprecedented shift toward earlier spring onsets of 3 days after 1975 (Rutishauser et al. 2007).

Changes in precipitation are a dominant driver of tree-growth reduction, forest decline (Bigler et al. 2006), and vegetation shifts (Riis Simonsen et al. 2013). On the scale of individual trees, extreme drought events decrease stomatal opening, transpiration, and CO2 assimilation, and may ultimately cause leaf senescence and loss. Quercus pubescens (downy oak) and Pinus sylvestris (Scots pine) stands in Switzerland, suffering from drought during the exceptionally hot and dry summer of 2003, assimilated CO2 only in the early morning and in the late afternoon with low rates or not at all during the most severe stress (Haldimann et al. 2008; Zweifel et al. 2009). During the same period in the southern Alps, Castanea sativa (chestnut) in exposed, forest-edge habitats experienced leaf withering starting in July and increased mortality (Conedera et al. 2010). Leaf level responses vary among species. For instance, young oaks recovered more rapidly and completely than young beech subjected to the same drought treatments (Gallé et al. 2007; Gallé and Feller 2007).

Long-term drought impacts on forests in Switzerland are most evident in the inner-Alpine dry forest ecosystems in the Valais and Grisons (Rigling et al. 2013). After a recent series of severe drought years (1996, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005), some Scots pine stands experienced mortality rates up to 50% (Rebetez and Dobbertin 2004; Dobbertin et al. 2005). Whereas single drought years had a negative impact on tree growth with a subsequent fast recovery (Lévesque et al. 2013, 2014b), multiple drought years resulted in long-lasting growth depressions, lagged recovery, and increased risk of tree death (Bigler et al. 2006). Changes in drought stress also drove rapid and lasting changes in tree species distributions in Switzerland during the Holocene. Mesophilous beech and Abies alba (silver fir) expanded without any apparent lag into continental mixed oak forests throughout Central Europe when the climate became more oceanic (i.e., cooler and moister summers, warmer winters) 8200 years ago, giving rise to today’s drought-sensitive beech forests (Tinner and Lotter 2001, 2006).

Complex responses to climate change in forest ecosystems

Climate-related growth decline and tree mortality in the low-elevation Scots pine forests of Switzerland (Dobbertin et al. 2005; Rigling et al. 2013) were mainly attributed to drought in spring and early summer (Affolter et al. 2010; Riis Simonsen et al. 2013; Lévesque et al. 2014a), the frequency of extreme drought years (Bigler et al. 2006), and interactions with parasites (Dobbertin and Riis Simonsen 2006), pests (Dobbertin et al. 2007; Wermelinger et al. 2008), and diseases (Heiniger et al. 2011). Within individual years, plant mortality depends upon whether drought impacts are reversible. Leaves may reach a point of no return during a severe drought period, with no recovery possible, and senesce before the end of the growing season. However, the response of tree growth to drought is non-linear; recovery after drought depends not only on the severity of drought, but also more importantly, on the frequency of drought years (Eilmann and Rigling 2012) and site conditions (Rigling et al. 2002; Lévesque et al. 2014a). Defining tipping points or thresholds for mortality is difficult as this depends not only on the drought sum over several years, but also on the susceptibility of the tree, which is influenced by many environmental (e.g., competition, herbivory) and intrinsic factors (e.g., tree species, age) and therefore varies from year to year (Huber et al. 2013; Feichtinger et al. 2014). In addition, feedbacks via the carbon storage of single trees might be important to recovery after severe drought (Eilmann et al. 2010; Lévesque et al. 2013).

Climate indirectly affects other critical drivers of forest dynamics such as the risk of insect outbreaks and fire (Büntgen et al. 2009; Zumbrunnen et al. 2009). Increased temperatures not only trigger drought stress rendering trees susceptible to insect attack, but also accelerate the lifecycles of insect pests (Wermelinger et al. 2008; Heiniger et al. 2011). Scots pine mortality in Valais resulted from the combined effects of drought, pests, and diseases. Likewise, the ongoing spruce decline in low-elevation Swiss forests was triggered by storms and subsequent bark beetle infestations and aggravated by dry summers (Temperli et al. 2013; Stadelmann et al. 2014). Climate also has indirect predisposing, and direct triggering roles on wildfire in Switzerland. On decadal-centennial scales, climate drives vegetation dynamics and therefore controls fuel availability (Zumbrunnen et al. 2009). In the short term, climate influences fuel moisture and therefore flammability, and the frequency of natural ignition by lightning (Conedera et al. 2006). Fire susceptibility in Switzerland has always varied regionally due to differences in climate and vegetation. The northern slope of the Alps and the Swiss Plateau are today, and were throughout the Holocene, by far the least fire-prone areas of the country (Tinner et al. 2005). However, wildfire activity in even the most fire-prone regions such as the southern slope of the Alps and the inner-Alpine valleys are characterized by strong human impacts, especially since the dramatic socio-economic and land-use changes of the last post-war period (Pezzatti et al. 2009; Zumbrunnen et al. 2012). Therefore, fire regimes only partially reflect the spatial, seasonal, and temporal patterns of rainfall, temperature, and wind (Zumbrunnen et al. 2009; Conedera et al. 2011). However, during recent decades, the climatic signal of fire occurrence became stronger as revealed by the increased number of large, stand-replacing fires in the Valais (Kipfer et al. 2011), and by the exceptional severity and extension of stand-replacing fire in the Alps during the hot and dry summer of 2003, including moderately fire-resistant and moist ecosystems such as beech forests (Ascoli et al. 2013).

Although observational data indicate many forest ecosystems in Switzerland are susceptible to projected climate changes on seasonal to decadal scales, sedimentary records argue for an amazing resilience on decadal to centennial scales of some forest species to strong climatic change during the Quaternary. European forest vegetation collapsed and re-expanded at least 11 times in response to glacial-interglacial climatic variability during the past 500,000 years (Tzedakis et al. 2001), and this repeated eradication and spontaneous reestablishment is well documented in Switzerland (Wegmüller 1992; Preusser et al. 2005). The mechanisms allowing forest species to survive climatic shifts up to approximately 10 °C are rapid migration and survival in favorable micro habitats (Willis and McElwain 2002; Kaltenrieder et al. 2010; Gavin et al. 2014). However, the fossil record also has many examples of extinctions in response to climate change. Climatic thresholds and tipping points for extinctions were usually crossed when temperature changes exceeded the Interglacial or Holocene climate variability of ±2–3 °C. Given that glacial conditions prevailed during the past 2.6 million years, species more tolerant to cold and dry conditions mostly survived, while many preferring warm and moist habitats went extinct (Willis and McElwain 2002). This ice age legacy may have created “empty niches” that may predispose European forest ecosystems to invasions by exotic species under global change conditions (Birks and Tinner 2016).

Observed changes in agriculture

Climate change impacts on agriculture in Switzerland

Climatic variability and extremes cause strong inter-annual fluctuations in the harvestable yields of arable crops and grasslands. Therefore, time series of historical yield data could be expected to reflect the impacts of past climate change. However, crop yields are subject to multiple factors in addition to climate, such as breeding, management, and technological change. Thus, climate change impacts on agriculture cannot be easily separated from other factors, and climate only partly explains yield variation. Assessing climate change impacts on crop yields in Switzerland is also complicated by complex topography because impacts vary with microclimatic conditions. Whereas rising temperatures may increase crop yields by, for instance, enabling cultivation at presently cooler, higher elevations, opposite effects can occur due to declining summer precipitation in regions where water is already limiting such as the Valais and western Switzerland. Such local and regional relationships between climate change and agricultural yields were evident in recent analyses that tracked small-scale changes in climate suitability for individual crops. Combining spatially explicit climate records with data and expert knowledge on weather-yield relationships revealed that from 1983 to 2010, grain maize yields benefitted from increasing temperatures (0.5 °C/decade) in many areas of Switzerland. Climate suitability for winter wheat decreased slightly during the same period due to either high temperature stress or excess water, which limited growth in some areas where summer precipitation and temperatures increased (Holzkämper et al. 2015).

Remains of historical and prehistorical agriculture broaden understanding of the complex interactions among climate, human innovation, and crop yields, by providing a long-term perspective that extends beyond historical records. Comparing today’s occurrence and abundance of crop-species pollen with surface samples from soils and sediments allows the reconstruction of former land use activities and crop yields over centuries and millennia (Behre 1981; Broström et al. 1998; Abraham and Kozáková 2012). Joint archeological and paleoecological records from the Swiss Plateau, the Central Alps and southern Switzerland show that since the introduction of cereal-based agriculture ca. 7500 years ago, harvest success was closely coupled to both changing climate and technological innovation (Gobet et al. 2003; Tinner 2003). Crop yields increased during warm-dry periods and declined during cold-wet phases. Cold-wet phases during the past 7500 years were comparable to the Little Ice Age period (LIA, ca. 1450–1850 AD) in regard to both magnitude and duration, while warm phases were comparable or slightly warmer (ca. 1 °C) than the twentieth century (Heiri et al. 2004). However, cold-wet and warm-dry phases (Haas et al. 1998) were superimposed on a long-term cooling trend (ca. −1 °C during the past 5000 years, until the 1980s), which was associated with increasing moisture. Nonetheless, technological progress throughout this cooling trend brought major yield increases.

Complex responses to climate change in agricultural systems

It is difficult to derive climatic thresholds and tipping points for crop yields based on field observations because farmers counteract potential risks by shifting crops, crop varieties, and through technological innovations. Limitations imposed by excessive soil moisture can be addressed by improving soil drainage and precipitation shortages by irrigation. Tipping points may occur in terms of farm economy when profits become negative due to high costs and low returns (Torriani et al. 2007a), but in Switzerland the buffering effect of farm subsidies is strong, which makes the influence of policy and prices more pronounced than the effects of climate change (Lehmann et al. 2013). Grassland and arable crop yields increased from the 1960s to the 1990s and then leveled off. This stagnation in crop yields was mainly caused by a change in the subsidy system that led to decreasing amounts of input use, not climatic change (Finger 2010). Similar cultural linkages are evident over the course of human history. Crop yields in Switzerland did not increase linearly along the past 7500 years. Instead, harvest success follows an exponential stepwise increase, probably mainly released by technological innovations (e.g., plows, scythes, introduction of new crops). Together with archeological observations (e.g., continuity of material culture), this argues for a certain long-term resilience of human societies, as long as climate change does not exceed the Holocene variability of ca. 2–3 °C.

Most significant crop yield losses are caused by extreme weather rather than by trends in mean climate. However, extreme conditions during spring, summer, and autumn have different effects, depending on the crop, as illustrated by comparing yield anomalies in years with distinct conditions during the three main seasons. Yield anomalies (relative to the 1988–2011 mean) reveal that with spring dryness in 2011, yields were consistently above average, whereas the dry summer of 2003 lowered yields of all crops except sugar beet. Extreme dryness in autumn 1991 had no effect on winter wheat, potatoes, and vegetables harvested in summer, but negative effects on maize and sugar beet harvested in autumn. The hot and dry summer of 2003 caused an average yield loss in Switzerland of around 20% relative to the mean for 1991–1999, equivalent to an economic loss of 500 million Swiss Francs (Keller and Fuhrer 2004). Summer drought stress negatively affects crop yields when leaves or whole plants surpass thresholds beyond which they are unable to recover (Messmer et al. 2011; Feller and Vaseva 2014). Although plants may recover after a severe drought period, individual leaves can be irreversibly damaged and senesce causing a decrease in photosynthetically active biomass, and thus crop yields. While drought stress develops slowly, heat stress can occur abruptly and even short episodes of high temperature can cause a severe decline in grain yields by impairing reproductive processes and grain formation (Porter and Gawith 1999). In managed grasslands, species are differently affected by extended drought periods, which can reduce productivity and trigger weed-control challenges. Year-to-year observations showed that forbs recruited more successfully than dominant grasses after drought, resulting in persistent changes in species composition and community structure (Stampfli and Zeiter 2004, 2008).

Paleoecological and archeological records and historical archives also show that agricultural productivity declined during periods typified by extreme conditions. During cold phases, population density as inferred from the number of settlements, artifacts, and tombs, strongly declined, leading to the abandonment of unsuitable (e.g., too cool, too moist) areas in Switzerland and other countries of western and central Europe (Maise 1999). Warm prehistorical periods allowed the cultivation of cereals at high altitudes in the subalpine belt of the Central Alps (Gobet et al. 2003). Historical archives record societal vulnerabilities to climatic impacts at centennial to decadal scales, including dramatic crop failures during the LIA, when famines, mortality, and emigration significantly increased in Switzerland and elsewhere in Europe (Pfister 1985). A crisis took place in the late 1430s during the early Spörer minimum, when severe winters and cool, humid summers resulted in grain shortages in most of Western and Central Europe (Camenisch et al. 2016). In contrast, during the year 1540, identified as one of the driest and hottest of the last millennium in Switzerland and most of Europe (Cook et al. 2015), an 11-month drought left soil moisture insufficient to support crops, and grapes desiccated on the vines (Wetter and Pfister 2013; Wetter et al. 2014). The eruption of Mount Tambora (Sumbawa, Indonesia) in April 1815 led to an extremely cool and humid “year without summer” the following year in Switzerland and much of Europe (Büntgen et al. 2015). Resulting crop failure caused widespread malnutrition, a significant decrease of fertility, and thousands of people dying of starvation, particularly in the early industrialized northeast of Switzerland (Krämer 2015; Luterbacher and Pfister 2015; Brönnimann and Krämer 2016).

In addition to the direct effects of climate variability, climate change indirectly impacts crop yields by altering pest cycles. The first flight of Cydia pomonella (codling moth), a pest of fruit trees, advanced by 10 days between 1972 and 2010 due to a shift to an earlier exceedance of a 15 °C mean threshold temperature in spring (Stöckli et al. 2012). Further warming projected by 2045–2075 would increase the likelihood of a second annual generation from 20% at present, to 70–100% (Stöckli et al. 2012). Walnut Husk fly (Rhagoletis completa), an exotic species that first invaded the Mediterranean region, recently reached Switzerland, likely by crossing the Alpine divide (Aluja et al. 2011). The fly is absent in areas where mean spring temperatures fall below 7 °C, but with recent increases in temperature, the width of the Alpine cold barrier progressively shrunk from 40 km in 1990 to around 20 km after 2000, and with projected temperature increases, will likely shrink to about 15 km (CH2011 2011). Thus, other cold-limited pest species may follow, and careful observation is needed along possible invasion routes. Invasions of new agricultural pests will force adaptations of plant protection strategies, possibly leading to higher costs in plant production.

Observations of the impacts of changing hydrology on agricultural soils reveal complex interactions between climate change and agriculture. Projected shifts to a more heterogeneous rainfall distribution and increased frequency and intensity of flooding events in Switzerland (CH2011 2011) could result in more frequent waterlogging of soils, and therefore alter the cycles of toxic elements such as arsenic (As) and mercury (Hg) that vary in bioavailability and mobilization according to soil redox potential (Thomas et al. 2001; Fee 2009; Frohne et al. 2012). In soil microcosm experiments designed to mimic the effects of projected increases in waterlogging on a range of Swiss soils, the mobility, bioavailability, and total concentrations of As in soil solution increase steadily with time of flooding and also with fertilization with manure. Many sites have high As and Hg concentration because of human activities (Pfeiffer et al. 2002; Le Bayon et al. 2011). These regions may experience higher metal release into soil solution as a consequence of projected shifts in precipitation patterns (i.e., increased winter flooding). Furthermore, many other potentially toxic metals and metalloids are known to show strong response to anoxic conditions in soil (Weber et al. 2009; Frohne et al. 2012). Thus, climate change will likely affect the mobility of metallic contaminants in Swiss soils.

Applying observations to improve climate impact assessments

Observations provide empirical grounding for climate change adaptation policies

A crucial challenge for climate impact studies is to identify vulnerabilities that require societal action to ensure the sustainable provision of ecosystem services. Recent climate change impact assessments for Switzerland and Europe (CH2014-Impacts 2014; Kovats et al. 2014) relied on climate impact models to formulate policy recommendations, using observational information either to develop or to underpin the modeling outputs. However, observations of climate change impacts on social and ecological systems are also invaluable in formulating adaptation policies because they provide realistic information at the local to regional scales where societal impacts occur and adaptation policies are needed, as well as a detailed empirical foundation to support investment decisions. Adaptation investments are particularly justified when agreement exists between modeled and observed climate change impacts.

Observations clearly document that temperature change will alter runoff regimes and water resources in Switzerland. Precipitation will likely decrease during summer (CH2011 2011), and therefore not compensate for evapotranspiration losses and result in decreasing runoff (FOEN 2012). This effect has already been observed in the Southern Alps. Runoff in the Ticino basin is decreasing (−2 mm/year), due to a very large increase of evapotranspiration (1.92 mm/year) and slightly decreasing precipitation (−0.22 mm/year). Furthermore, these observations are consistent with data from drought summers like 2003 that indicate the consequences of climatic conditions that are extremes in the historical record but are projected to occur more frequently, or even regularly, in the future (Schär et al. 2004). Thus, historical discharge data support projections concluding that temperature increases would lead to a new hydrologic regime, with low flows during summer and high flows during winter, effectively the opposite of the prevailing historical conditions (FOEN 2012).

Observations provide a consistent outlook for climate change risks to crop yields associated with changes in the frequency of extreme weather. At all temporal scales of observations, the negative impacts of extreme weather and climate are documented. Thus, projected increases in drought frequency and intensity, and more frequent extreme temperature excursions should reduce crop yields (Holzkämper and Fuhrer 2015). Regional climate models project the largest reductions in precipitation and increases in temperature during the summer months (CH2011 2011) when extreme weather has the strongest impacts on yields of cereals and potato. Therefore, significant risks for future crop yields exist in regions with limited water resources, and where the demand for additional irrigation to cope with increasing summer drought stress may trigger conflicts among different water users (Klein et al. 2013). These observation-based interpretations agree with modeled projections (CH2014-Impacts 2014); however, if the observational perspective becomes longer and/or the considered climate variability more extreme, inconsistencies can appear. Similarly, factors missing in the models may contribute to data-modeling inconsistencies.

Observations identify model-data inconsistencies that require further investigation

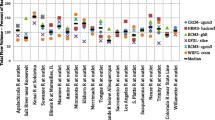

Observations of climate change impacts are crucial for identifying inconsistencies between models and empirical data that require further investigation. Several regional climate model scenarios project an increase in the frequency of intense precipitation in the Alps during spring, summer, and fall, which could cause more frequent floods (Rajczak et al. 2013; Fischer et al. 2015; Giorgi et al. 2016). However, sedimentary evidence from the Alps reveals that warm-season floods were more frequent during cooler periods of the past (Stewart et al. 2011; Glur et al. 2013; Amann et al. 2015). Likewise, one of the most complete flood records north of the Alps (Ammersee in southern Germany) shows maxima in the frequency distribution of floods for colder periods of the LIA (Czymzik et al. 2010). This unambiguous evidence suggests that hydrological extremes are not necessarily a close function of meteorological extremes, but can also arise from an adverse sequence of moderate weather conditions such as rain-on-snow floods or changes in the frequency of synoptic weather types. Whether such weather sequences are represented by climate impact models remains an open question that deserves further attention. Similarly, observations are critical for identifying emergent risks to the hydrological system that are not included in climate impact models. Projections of glacier loss from the Alps are extreme, with losses of 90% of glacier mass projected by 2100 AD (Marty et al. 2014). However, glacier darkening as a positive feedback is absent from models (Huss 2012). The presence of soot particles in snow reduces albedo (Flanner et al. 2007), which increases snowmelt, the exposed ice area, and the altitude of the seasonal melt line. Because glacier darkening could cause glacier loss to exceed projected rates, quantifying and reducing the albedo errors due to glacier darkening is a priority for improving simulations of climate change impacts on the hydrological cycle in the Alps.

The main historical and prehistorical finding that under warm and dry conditions crop yields increased, contrasts with short-term observations and model projections implying that yields of current crop varieties may reach a temperature limit and significantly decrease in response to further warming (Torriani et al. 2007a, b). The contrast may be explained by the different temporal scales observed (inter-annual variability vs. decadal and centennial trends) as well as fundamental differences in land-use strategies between early, low-population, autarchic agrarian economies, and modern, densely populated, industrialized and globalized economies. The original varieties of the prehistorical and historical cereals cultivated in Switzerland originate from regions with hot-dry subtropical climates of the Near East (Jacomet and Kreuz 1999) and are naturally less adapted to the wet and cool conditions occurring in Switzerland. Thus, adaptations of varieties to cool-humid periods may have taken centuries, while warmth and drought-adapted varieties were always available from neighboring Mediterranean areas (Tinner et al. 2007). Inconsistencies between paleo observations and modeling outputs are also evident in forest ecosystems. For instance, ecophysiological parameters in dynamic vegetation models were recently reassessed to allow more realistic responses of keystone species such as Abies alba under global warming conditions (Ruosch et al. 2016). More inconsistencies are expected for other important tree species, given that today’s species ranges, which are often used to project future ecosystem conditions (e.g., with species distribution models [SDMs], bioclimatic models, niche models), are strongly influenced by millennia of land use and forestry practices (Birks and Tinner 2016). A promising novel approach to reduce such inconsistencies is to combine dynamic process-based models with paleoecological evidence to produce paleo-validated scenarios of future ecosystem dynamics (Henne et al. 2015; Ruosch et al. 2016).

Identifying adaptation strategies for complex systems

Climate change impacts on complex social and ecological systems are often constrained by multiple environmental factors (e.g., land use history, soils, human innovation). Thus, developing climate adaptation strategies requires integrative assessments of multiple impact factors. Whereas impact models, by necessity, focus on a limited number of systems and processes, observations have no such intrinsic limitations, and can evaluate the impacts of multiple controlling factors. For example, identifying the processes that maintained past biodiversity over millennia of changing climate and land use is key to conserving ecologically and culturally valuable alpine meadows (Fig. 2). Given that an increase in mean annual temperature lengthens the growing season in alpine ecosystems (i.e., around 15 days/1 °C increase; Schröter 1923; Defila and Clot 2005), an upward shift of forests into the alpine belt is a legitimate threat to alpine meadows (Theurillat et al. 1998; Theurillat and Guisan 2001). Strong reductions or extinctions of many alpine species may seem likely, especially when climate change impacts on alpine habitat availability are evaluated with species distribution models at extremely coarse spatial scales (e.g., 50 × 50 km grid; Thuiller et al. 2005). This rather pessimistic view is counterbalanced by paleoecological evidence. Indeed, alpine species must have persisted during previous interglacials, when temperatures were warmer than during the Holocene (e.g., Eemian 120,000 years ago, ca. +3–4 °C if compared to preindustrial values; Aalbersberg and Litt 1998). Paleo-validated fine scale dynamic modeling simulations and spatially resolved observations reveal that microtopography and soil conditions may limit upslope expansion of forests and thus drastic species losses (Henne et al. 2011; Scherrer et al. 2011). Furthermore, traditional pasturing and other practices that limit tree colonization and biomass accumulation can allow alpine meadows to persist in the most favorable places, and thereby limit the loss of alpine species (Theurillat et al. 1998; Theurillat and Guisan 2001; Weigl and Knowles 2014). Very similar conclusions recommending intermediate levels of grazing and fire disturbance to maintain species diversity under global warming conditions were reached by paleoecological studies that analyzed the millennial-long influence of human impact on meadows at and above treeline and also lowland meadows (Colombaroli et al. 2010; Colombaroli and Tinner 2013). Although management efforts may mitigate losses, populations of alpine species will ultimately shrink, especially in areas where the extent of the alpine belt is presently limited, such as in the Prealps. Smaller populations will mean that the long-term persistence (millennia) of alpine species will be at risk in a warmer world.

Examples of applying observations to understand and mitigate climate change impacts on the biodiversity of alpine meadows. (Top) Observations of upslope invasions and reconstructions of Holocene treeline dynamics provide a strong empirical basis for the susceptibility of alpine meadows to temperature-driven change. (Center) Models are highly valuable for projecting potential outcomes. However, inconsistencies between models and observations demonstrate where understanding is limited and model refinements are needed. (Bottom) Observations identify processes and effective management policies that mitigate climate change impacts on biodiversity. Complex topography provides diverse microclimates that promote diversity in alpine meadows and can buffer climate change impacts. Intermediate disturbances from alpine pasturing and fires promoted diversity in alpine meadows during the Holocene and are critical to sustaining alpine biodiversity in a warming climate

Observations provide understanding of the resiliency of forests to climate change and can broaden management options by documenting native forest types that are absent from the modern landscape. Projected increases in the frequency of drought events (CH2011 2011) would have a significant or even dramatic impact on forest ecosystems, starting with the most vulnerable forests on dry sites. However, Quaternary records show that Swiss forests can respond within decades to climatic warming and/or changes in moisture availability, through changes in forest structure, species abundances and distributions (Tinner and Lotter 2001). On the basis of paleoecological reconstructions, species with artificially widened realized niches that prefer oceanic and/or cool conditions are particularly vulnerable (e.g., beech, spruce; Tinner et al. 2013). However, drought resistant and/or thermophilous species that were partly or even substantially reduced by land use and forestry may expand rapidly by the end of this century (Bugmann et al. 2014; Henne et al. 2015). This concerns extant species (e.g., A. alba, Q. pubescens, Tilia cordata), species arriving from the neighboring Mediterranean region (e.g., Quercus ilex, Ostrya carpinifolia, Laurus nobilis), and also exotics (e.g., Trachycarpus fortunei, Cinnamomum camphora) that have progressively spread in the Southern Alps since the 1970s due in part to increasing winter temperatures (Walther et al. 2002; Berger et al. 2007). Furthermore, broadleaf trees (e.g., Acer pseudoplatanus, F. sylvatica, Fraxinus excelsior, Ilex aquifolium, Prunus avium, Quercus petraea, T. cordata) that are sensitive to late frosts during bud-break (Kollas et al. 2014) will extend their range upward.

The fossil record suggests that today’s communities will not be able to resist these invasions once certain thresholds or tipping points are reached (Tinner and Lotter 2006). The quantification of such thresholds and tipping points can be achieved by combining the fossil record with modeling approaches. For instance, combined fossil and modeling evidence suggests that spruce may collapse in the subalpine belt of the central Alps if annual precipitation decreases by only 150–250 mm (Heiri et al. 2006; Henne et al. 2011). Given the paramount importance of spruce for the subalpine forests in Switzerland, management strategies involving the gradual reduction of the spruce and beech dominance in Swiss subalpine forests, with targeted replacement by species that were dominant during drier intervals (e.g., A. alba, Q. petraea, T. cordata), may prevent future ecological and economic disasters (Tinner et al. 2013; Schwörer et al. 2014b). Such management actions may be especially important in lowland ecosystems where lags between biotic responses and climate change are longer than in mountain ecosystems (Bertrand et al. 2011).

Due to the complexity of forest ecosystems and the longevity of trees, observations and reconstructions are critical for calibrating and validating models capable of providing projections of climate change impacts on forest ecosystems (Rasche et al. 2011). For example, species distribution models are powerful tools for identifying the climatic niche of individual species (Guisan and Thuiller 2005). When calibrated with modern distribution data and applied to climate projections, such models can identify suitable future habitats in a changing climate. However, when non-climatic factors constrain present distributions, predictive models can seriously underestimate or overestimate changing distributions in response to climate warming (Tinner et al. 2013). Refining model projections with evidence of past distributions under warmer and drier climate has greatly improved understanding of species potential in a warmer and drier future, and therefore expanded management options (Henne et al. 2015; Ruosch et al. 2016).

Conclusions

Observations of climate change impacts in Switzerland demonstrate the value of, and potential to improve climate change impact assessments with, observational data. Although models are routinely used to make projections, they are by definition simplifications of nature that provide numeric summaries of what is known, and may oversimplify certain change directions. In particular, projections that rely on correlative models should be treated with caution, given that the observational evidence is replete with examples of non-linear responses to climatic change. Whereas impact models typically focus on one system, and by necessity include a limited number of processes, system responses depend on multiple components and are often stochastic. Observational data can naturally integrate the impacts of multiple cultural and natural factors, as well as interactions among systems that can amplify or buffer climatic impacts. Observations are needed to validate and improve model projections, identify emergent risks, and also identify adaptation strategies that arise from complex interactions that are difficult to simulate.

References

Aalbersberg G, Litt T (1998) Multiproxy climate reconstructions for the Eemian and Early Weichselian. J Quat Sci 13:367–390. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1417(1998090)13:5<367::AID-JQS400>3.0.CO;2-I

Abraham V, Kozáková R (2012) Relative pollen productivity estimates in the modern agricultural landscape of Central Bohemia (Czech Republic). Rev Palaeobot Palynol 179:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2012.04.004

Addor N, Rössler O, Köplin N, Huss M, Weingartner R, Seibert J (2014) Robust changes and sources of uncertainty in the projected hydrological regimes of Swiss catchments. Water Resour Res 50:7541–7562. doi:10.1002/2014WR015549

Affolter P, Büntgen U, Esper J, Rigling A, Weber P, Luterbacher J, Frank D (2010) Inner Alpine conifer response to 20th century drought swings. Eur J For Res 129:289–298. doi:10.1007/s10342-009-0327-x

Aluja M, Guillén L, Rull J, Höhn H, Frey J, Graf B, Samietz J (2011) Is the alpine divide becoming more permeable to biological invasions?—insights on the invasion and establishment of the Walnut Husk Fly, Rhagoletis completa (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Switzerland. Bull Entomol Res 101:451–465. doi:10.1017/S0007485311000010

Amann B, Szidat S, Grosjean M (2015) A millennial-long record of warm season precipitation and flood frequency for the north-western Alps inferred from varved lake sediments: implications for the future. Quat Sci Rev 115:89–100. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.03.002

Ammann B, van Raden UJ, Schwander J, Eicher U, Gilli A, Bernasconi SM, van Leeuwen JFN, Lischke H, Brooks SJ, Heiri O, Nováková K, van Hardenbroek M, von Grafenstein U, Belmecheri S, van der Knaap WO, Magny M, Eugster W, Colombaroli D, Nielsen E, Tinner W, Wright HE (2013) Responses to rapid warming at termination 1a at Gerzensee (Central Europe): primary succession, albedo, soils, lake development, and ecological interactions. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 391:111–131. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.11.009

Ascoli D, Castagneri D, Valsecchi C, Conedera M, Bovio G (2013) Post-fire restoration of beech stands in the Southern Alps by natural regeneration. Ecol Eng 54:210–217. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.01.032

Behre K-E (1981) Interpretation of anthropogenic indicators in pollen diagrams. Pollen Spores 23:225–245

Berger S, Söhlke G, Walther G-R, Pott R (2007) Bioclimatic limits and range shifts of cold-hardy evergreen broad-leaved species at their northern distributional limit in Europe. Phytocoenologia 37:523–539. doi:10.1127/0340-269X/2007/0037-

Bertrand R, Lenoir J, Piedallu C, Riofrio-Dillon G, de Ruffray P, Vidal C, Pierrat J-C, Gegout J-C (2011) Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests. Nature 479:517–520. doi:10.1038/nature10548

Bigler C, Braker OU, Bugmann H, Dobbertin M, Riis Simonsen J (2006) Drought as an inciting mortality factor in Scots pine stands of the Valais, Switzerland. Ecosystems 9:330–343. doi:10.1007/s10021-005-0126-2

Bindi M, Olesen JE (2011) The responses of agriculture in Europe to climate change. Reg Environ Chang 11:151–158. doi:10.1007/s10113-010-0173-x

Birks HJB, Tinner W (2016) Past forests of Europe. In: San-Miguel-Ayanz J, de Rigo D, Caudulio G, Houston Durrant G, Mauri A (eds) European Atlas of forest tree species. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, pp 36–39. doi:10.2788/038466

Birsan M-V, Molnar P, Burlando P, Pfaundler M (2005) Streamflow trends in Switzerland. J Hydrol 314:312–329. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.06.008

Blanc P, Schädler B (2014) Water in Switzerland—an overview. Swiss Hydrological Commission, Bern

Bolli JC, Riis Simonsen J, Bugmann H (2007) The influence of changes in climate and land-use on regeneration dynamics of Norway spruce at the treeline in the Swiss Alps. Silva Fenn 41:55–70. doi:10.14214/sf.307

Brönnimann S, Krämer D (2016) Tambora and the “year without a summer” of 1816. Geogr Bernensia G90:48. doi:10.4480/GB2016.G90.01

Brönnimann S, Appenzeller C, Croci-Maspoli M, Fuhrer J, Grosjean M, Hohmann R, Ingold K, Knutti R, Liniger MA, Raible CC, Röthlisberger R, Schär C, Scherrer SC, Strassmann K, Thalmann P (2014) Climate change in Switzerland: a review of physical, institutional, and political aspects. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 5:461–481. doi:10.1002/wcc.280

Broström A, Gaillard M-J, Ihse M, Odgaard B (1998) Pollen-landscape relationships in modern analogues of ancient cultural landscapes in southern Sweden? A first step towards quantification of vegetation openness in the past. Veg Hist Archaeobot 7:189–201. doi:10.1007/BF01146193

Bugmann H, Pfister C (2000) Impacts of interannual climate variability on past and future forest composition. Reg Environ Chang 1:112–125. doi:10.1007/s101130000015

Bugmann H, Brang P, Elkin C, Henne PD, Jakoby O, Lévesque M, Lischke H, Psomas A, Riis Simonsen J, Wermelinger B, Zimmermann NE (2014) Climate change impacts on tree species, forest properties, and ecosystem services. In: Raible CC, Strassman KM (eds) CH-2014 impacts, toward quantitative scenarios of climate change impacts in Switzerland. Published by OCCR, FOEN, MeteoSwiss, C2SM, Agroscope, and ProClim, Bern, pp 79–89

Bühlmann T, Hiltbrunner E, Körner C (2014) Alnus viridis expansion contributes to excess reactive nitrogen release, reduces biodiversity and constrains forest succession in the Alps. Alp Bot 124:187–191. doi:10.1007/s00035-014-0134-y

Büntgen U, Frank D, Liebhold A, Johnson D, Carrer M, Urbinati C, Grabner M, Nicolussi K, Levanic T, Esper J (2009) Three centuries of insect outbreaks across the European Alps. New Phytol 182:929–941. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02825.x

Büntgen U, Trnka M, Krusic PJ, Kyncl T, Kyncl J, Luterbacher J, Zorita E, Ljungqvist FC, Auer I, Konter O, Schneider L, Tegel W, Štěpánek P, Brönnimann S, Hellmann L, Nievergelt D, Esper J (2015) Tree-ring amplification of the early nineteenth-century summer cooling in Central Europe. J Clim 28:5272–5288. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00673.1

Burga CA (1988) Swiss vegetation history during the last 18000 years. New Phytol 110:581–602. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1988.tb00298.x

Camenisch C, Keller KM, Salvisberg M, Amann B, Bauch M, Blumer S, Brázdil R, Brönnimann S, Büntgen U, Campbell BMS, Fernández-Donado L, Fleitmann D, Glaser R, González-Rouco F, Grosjean M, Hoffmann RC, Huhtamaa H, Joos F, Kiss A, Kotyza O, Lehner F, Luterbacher J, Maughan N, Neukom R, Novy T, Pribyl K, Raible CC, Riemann D, Schuh M, Slavin P, Werner JP, Wetter O (2016) The early Spörer minimum—a period of extraordinary climate and socio-economic changes in Western and Central Europe. Clim Past Discuss 1–33. doi:10.5194/cp-2016-7

CH2011 (2011) Swiss climate change scenarios CH2011. Published by C2SM, MeteoSwiss, ETH, NCCR Climate, and OcCC, Zurich

CH2014-Impacts (2014) Toward quantitative scenarios of climate change impacts in Switzerland. Published by OCCR, FOEN, MeteoSwiss, C2SM, Agroscope, and ProClim, Bern

Christensen JH, Christensen OB (2003) Climate modelling: severe summertime flooding in Europe. Nature 421:805–806. doi:10.1038/421805a

Cole K (1985) Past rates of change, species richness, and a model of vegetational inertia in the Grand Canyon, Arizona. Am Nat 125:289–303. doi:10.1086/284341

Colombaroli D, Tinner W (2013) Determining the long-term changes in biodiversity and provisioning services along a transect from Central Europe to the Mediterranean. The Holocene 23:1625–1634. doi:10.1177/0959683613496290

Colombaroli D, Henne PD, Kaltenrieder P, Gobet E, Tinner W (2010) Species responses to fire, climate and human impact at tree line in the Alps as evidenced by palaeo-environmental records and a dynamic simulation model. J Ecol 98:1346–1357. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01723.x

Conedera M, Cesti G, Pezzatti GB, Zumbrunnen T, Spinedi F (2006) Lightning-induced fires in the Alpine region: an increasing problem. In: Viegas DX (ed) V International Conference on Forest Fire Research. ADAI/CEIF University of Coimbra, Figueira da Foz

Conedera M, Barthold F, Torriani D, Pezzatti GB (2010) In: Horticulturae A (ed) Drought sensitivity of Castanea sativa: case study of summer 2003 in the Southern Alps. International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, pp 297–302

Conedera M, Torriani D, Neff C, Ricotta C, Bajocco S, Pezzatti GB (2011) Using Monte Carlo simulations to estimate relative fire ignition danger in a low-to-medium fire-prone region. For Ecol Manag 261:2179–2187. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.08.013

Cook ER, Seager R, Kushnir Y, Briffa KR, Büntgen U, Frank D, Krusic PJ, Tegel W, van der Schrier G, Andreu-Hayles L, Baillie M, Baittinger C, Bleicher N, Bonde N, Brown D, Carrer M, Cooper R, Cufar K, Dittmar C, Esper J, Griggs C, Gunnarson B, Günther B, Gutierrez E, Haneca K, Helama S, Herzig F, Heussner K-U, Hofmann J, Janda P, Kontic R, Köse N, Kyncl T, Levanic T, Linderholm H, Manning S, Melvin TM, Miles D, Neuwirth B, Nicolussi K, Nola P, Panayotov M, Popa I, Rothe A, Seftigen K, Seim A, Svarva H, Svoboda M, Thun T, Timonen M, Touchan R, Trotsiuk V, Trouet V, Walder F, Wazny T, Wilson R, Zang C (2015) Old World megadroughts and pluvials during the Common Era. Sci Adv 1:e1500561–e1500561. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500561

Crawford RMM (2008) Plants at the margin: ecological limits and climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Czymzik M, Dulski P, Plessen B, von Grafenstein U, Naumann R, Brauer A (2010) A 450 year record of spring-summer flood layers in annually laminated sediments from Lake Ammersee (southern Germany). Water Resour Res 46:W11528. doi:10.1029/2009wr008360

Defila C, Clot B (2001) Phytophenological trends in Switzerland. Int J Biometeorol 45:203–207. doi:10.1007/s004840100101

Defila C, Clot B (2005) Phytophenological trends in the Swiss Alps, 1951-2002. Meteorol Zeitschrift 14:191–196. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2005/0021

Dobbertin M, Riis Simonsen J (2006) Pine mistletoe (Viscum album ssp. austriacum) contributes to Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) mortality in the Rhone valley of Switzerland. For Pathol 36:309–322. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0329.2006.00457.x

Dobbertin M, Mayer P, Wohlgemuth T, Feldmeyer-Christe E, Graf U, Zimmermann NE, Rigling A (2005) The decline of Pinus sylvestris L. forests in the swiss rhone valley: a result of drought stress? Phyton (B Aires) 45:153–156

Dobbertin M, Wermelinger B, Bigler C, Bürgi M, Carron M, Forster B, Gimmi U, Rigling A (2007) Linking increasing drought stress to Scots pine mortality and bark beetle infestations. Sci World J 7:231–239. doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.58

Eilmann B, Rigling A (2012) Tree-growth analyses to estimate tree species’ drought tolerance. Tree Physiol 32:178–187. doi:10.1093/treephys/tps004

Eilmann B, Buchmann N, Siegwolf R, Saurer M, Cherubini P, Rigling A (2010) Fast response of Scots pine to improved water availability reflected in tree-ring width and δ13C. Plant Cell Environ 33:1351–1360. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02153.x

Elkin C, Gutiérrez AG, Leuzinger S, Manusch C, Temperli C, Rasche L, Bugmann H (2013) A 2 °C warmer world is not safe for ecosystem services in the European Alps. Glob Chang Biol 19:1827–1840. doi:10.1111/gcb.12156

Elkin C, Giuggiola A, Rigling A, Bugmann H (2015) Short- and long-term efficacy of forest thinning to mitigate drought impacts in mountain forests in the European Alps. Ecol Appl 25:1083–1098. doi:10.1890/14-0690.1

Fee DB (2009) Arsenic. In: Dobbs MR (ed) Clinical neurotoxicology. Syndromes, substances, environments. Saunders, Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 273–276

Feichtinger LM, Eilmann B, Buchmann N, Rigling A (2014) Growth adjustments of conifers to drought and to century-long irrigation. For Ecol Manag 334:96–105. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2014.08.008

Feller U, Vaseva II (2014) Extreme climatic events: impacts of drought and high temperature on physiological processes in agronomically important plants. Front Environ Sci. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2014.00039

Finger R (2010) Evidence of slowing yield growth—the example of Swiss cereal yields. Food Policy 35:175–182. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.11.004

Fischer AM, Keller DE, Liniger MA, Rajczak J, Schär C, Appenzeller C (2015) Projected changes in precipitation intensity and frequency in Switzerland: a multi-model perspective. Int J Climatol 35:3204–3219. doi:10.1002/joc.4162

Flanner MG, Zender CS, Randerson JT, Rasch PJ (2007) Present-day climate forcing and response from black carbon in snow. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/2006jd008003

FOEN (2012) Effects of climate change on water resources and waters. Federal Office for the Environment, Bern

Frohne T, Rinklebe J, Langer U, Du Laing G, Mothes S, Wennrich R (2012) Biogeochemical factors affecting mercury methylation rate in two contaminated floodplain soils. Biogeosciences 9:493–507. doi:10.5194/bg-9-493-2012

Gallé A, Feller U (2007) Changes of photosynthetic traits in beech saplings (Fagus sylvatica) under severe drought stress and during recovery. Physiol Plant 131:412–421. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.00972.x

Gallé A, Haldimann P, Feller U (2007) Photosynthetic performance and water relations in young pubescent oak (Quercus pubescens) trees during drought stress and recovery. New Phytol 174:799–810. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02047.x

Gavin DG, Fitzpatrick MC, Gugger PF, Heath KD, Rodríguez-Sánchez F, Dobrowski SZ, Hampe A, Hu FS, Ashcroft MB, Bartlein PJ, Blois JL, Carstens BC, Davis EB, de Lafontaine G, Edwards ME, Fernandez M, Henne PD, Herring EM, Holden ZA, Kong W, Liu J, Magri D, Matzke NJ, McGlone MS, Saltré F, Stigall AL, Tsai Y-H.E, Williams JW (2014) Climate refugia: joint inference from fossil records, species distribution models and phylogeography. New Phytol 204:37–54. doi:10.1111/nph.12929

Gehrig-Fasel J, Guisan A, Zimmermann NE (2007) Tree line shifts in the Swiss Alps: climate change or land abandonment? J Veg Sci 18:571–582. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2007.tb02571.x

Giorgi F, Torma C, Coppola E, Ban N, Schär C, Somot S (2016) Enhanced summer convective rainfall at Alpine high elevations in response to climate warming. Nat Geosci. doi:10.1038/ngeo2761

Glur L, Wirth SB, Büntgen U, Gilli A, Haug GH, Schär C, Beer J, Anselmetti FS (2013) Frequent floods in the European Alps coincide with cooler periods of the past 2500 years. Sci Rep 3:2770. doi:10.1038/srep02770

Gobet E, Tinner W, Hochuli PA, van Leeuwen JFN, Ammann B (2003) Middle to Late Holocene vegetation history of the Upper Engadine (Swiss Alps): the role of man and fire. Veg Hist Archaeobot 12:143–163. doi:10.1007/s00334-003-0017-4

Gottfried M, Pauli H, Futschik A, Akhalkatsi M, Barancok P, Benito Alonso JL, Coldea G, Dick J, Erschbamer B, Fernandez Calzado MR, Kazakis G, Krajci J, Larsson P, Mallaun M, Michelsen O, Moiseev D, Moiseev P, Molau U, Merzouki A, Nagy L, Nakhutsrishvili G, Pedersen B, Pelino G, Puscas M, Rossi G, Stanisci A, Theurillat J-P, Tomaselli M, Villar L, Vittoz P, Vogiatzakis I, Grabherr G (2012) Continent-wide response of mountain vegetation to climate change. Nat Clim Chang 2:111–115. doi:10.1038/nclimate1329

Grabherr G, Gottfried M, Pauli H (1994) Climate effects on mountain plants. Nature 369:448. doi:10.1038/369448a0

Guisan A, Thuiller W (2005) Predicting species distribution: offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol Lett 8:993–1009. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00792.x

Guisan A, Theurillat J-P, Kienast F (1998) Predicting the potential distribution of plant species in an alpine environment. J Veg Sci 9:65–74. doi:10.2307/3237224

Haas JN, Richoz I, Tinner W, Wick L (1998) Synchronous Holocene climatic oscillations recorded on the Swiss Plateau and at timberline in the Alps. The Holocene 8:301–309. doi:10.1191/095968398675491173

Haldimann P, Gallé A, Feller U (2008) Impact of an exceptionally hot dry summer on photosynthetic traits in oak (Quercus pubescens) leaves. Tree Physiol 28:785–795. doi:10.1093/treephys/28.5.785

Hänggi P, Weingartner R (2011) Inter-annual variability of runoff and climate within the Upper Rhine River basin, 1808–2007. Hydrol Sci J 56:34–50. doi:10.1080/02626667.2010.536549

Heiniger U, Theile F, Riis Simonsen J, Rigling D (2011) Blue-stain infections in roots, stems and branches of declining Pinus sylvestris trees in a dry inner alpine valley in Switzerland. For Pathol 41:501–509. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0329.2011.00713.x

Heiri O, Tinner W, Lotter AF (2004) Evidence for cooler European summers during periods of changing meltwater flux to the North Atlantic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:15285–15288. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406594101

Heiri C, Bugmann H, Tinner W, Heiri O, Lischke H (2006) A model-based reconstruction of Holocene treeline dynamics in the Central Swiss Alps. J Ecol 94:206–216. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01072.x

Heiri O, Koinig KA, Spötl C, Barrett S, Drescher-Schneider R, Gaar D, Ivy-Ochs S, Kerschner H, Luetscher M, Moran A, Nicolussi K, Preusser F, Schmidt R, Schoeneich P, Schwörer C, Sprafke T, Terhorst B, Tinner W (2014) Palaeoclimate records 60–8 ka in the Austrian and Swiss Alps and their forelands. Quat Sci Rev 106:186–205. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.05.021

Heiri O, Ilyashuk B, Millet L, Samartin S, Lotter AF (2015) Stacking of discontinuous regional palaeoclimate records: chironomid-based summer temperatures from the Alpine region. The Holocene 25:137–149. doi:10.1177/0959683614556382

Henne PD, Elkin C, Reineking B, Bugmann H, Tinner W (2011) Did soil development limit spruce (Picea abies) expansion in the Central Alps during the Holocene? Testing a palaeobotanical hypothesis with a dynamic landscape model. J Biogeogr 38:933–949. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02460.x

Henne PD, Elkin C, Franke J, Colombaroli D, Calò C, La Mantia T, Pasta S, Conedera M, Dermody O, Tinner W (2015) Reviving extinct Mediterranean forest communities may improve ecosystem potential in a warmer future. Front Ecol Environ 13:356–362. doi:10.1890/150027

Hewitson BC, Janetos AC, Carter TR, Giorgi F, Jones RG, Kwon W-T, Mearns LO, Schipper ELF, van Aalst M (2014) Regional context. In: Barros VR, Field CB, Dokken DJ, Mastrandrea MD, Mach KJ, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL (eds) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: regional aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel of climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1133–1197

Holzkämper A, Fuhrer J (2015) The impact of climate change on maize cultivation in Switzerland. Agrar Schweiz 6:440–447

Holzkämper A, Fossati D, Hiltbrunner J, Fuhrer J (2015) Spatial and temporal trends in agro-climatic limitations to production potentials for grain maize and winter wheat in Switzerland. Reg Environ Chang 15:109–122. doi:10.1007/s10113-014-0627-7

Huber R, Rigling A, Bebi P, Brand FS, Briner S, Buttler A, Elkin C, Gillet F, Grêt-Regamey A, Hirschi C (2013) Sustainable land use in mountain regions under global change: synthesis across scales and disciplines. Ecol Soc 18:20. doi:10.5751/ES-05499-180336

Huss M (2012) Extrapolating glacier mass balance to the mountain-range scale: the European Alps 1900-2100. Cryosphere 6:713–727. doi:10.5194/tc-6-713-2012

IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Core Writing Team, Pachauri RK, Meyer LA (eds), IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland

Jacomet S, Kreuz A (1999) Archäobotanik: Aufgaben, Methoden und Ergebnisse vegetations-und agrargeschichtlicher Forschung. Ulmer

Johnson DM, Büntgen U, Frank DC, Kausrud K, Haynes KJ, Liebhold AM, Esper J, Stenseth NC (2010) Climatic warming disrupts recurrent Alpine insect outbreaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:20576–20581. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010270107

Kaltenrieder P, Procacci G, Vannière B, Tinner W (2010) Vegetation and fire history of the Euganean Hills (Colli Euganei) as recorded by Lateglacial and Holocene sedimentary series from Lago della Costa (northeastern Italy). The Holocene 20:679–695. doi:10.1177/0959683609358911

Kammer PM, Schöb C, Choler P (2007) Increasing species richness on mountain summits: upward migration due to anthropogenic climate change or re-colonisation? J Veg Sci 18:301–306. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2007.tb02541.x

Keller F, Fuhrer J (2004) Die Landwirtschaft und der Hitzesommer 2003. Agrarforschung 11:403–410

King G, Fonti P, Nievergelt D, Büntgen U, Frank D (2013) Climatic drivers of hourly to yearly tree radius variations along a 6 °C natural warming gradient. Agric For Meteorol 168:36–46. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.08.002

Kipfer T, Moser B, Egli S, Wohlgemuth T, Ghazoul J (2011) Ectomycorrhiza succession patterns in Pinus sylvestris forests after stand-replacing fire in the Central Alps. Oecologia 167:219–228. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-1981-5

Klein T, Holzkämper A, Calanca P, Seppelt R, Fuhrer J (2013) Adapting agricultural land management to climate change: a regional multi-objective optimization approach. Landsc Ecol 28:2029–2047. doi:10.1007/s10980-013-9939-0