Abstract

The dry forests of Latin America are among the most dynamic deforestation frontiers in the world and are important carbon and biodiversity reservoirs. Our knowledge on the spatial patterns of deforestation and its proximate drivers remains partial though. We used the full Landsat image archive to reconstruct deforestation and post-deforestation dynamics between 1987 and 2012 for the entire Paraguayan Chaco, where deforestation has been rampant recently. Our classification resulted in reliable land-use change maps (86.16%), highlighting drastic forest losses of almost 44,000 km2 between 1987 and 2012, equaling a deforestation rate of 27% and about 1% yearly, predominantly for grasslands. These likely represented new pastures, making pasture expansion the dominant proximate cause of deforestation. Cropland expansion, in contrast, only played a minor role as a proximate deforestation cause in the Paraguayan Chaco. Deforestation more than doubled between 2001 and 2012 (~29,000 km2) compared to 1987–2000 (~14,000 km2), due to leakage effects from the deforestation ban in the Paraguayan Atlantic Forests in 2004. Interestingly, while grasslands expanded in the Paraguayan Chaco between 1987 and 2000, cattle numbers decreased during the same time period, though strongly increased since. This apparent decoupling of area change and land-use intensity may indicate that the Paraguayan Chaco experienced an amplification period during the 1990s followed by an intensification period since 2001. Thus, our results highlight the need for both, a more detailed monitoring of post-deforestation dynamics and a land systems perspective in order to understand deforestation frontiers and thus ultimately to identify strategies to better balance production and conservation goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The expansion of agriculture into tropical forests is an important driver of global climate change and biodiversity loss (Goodale et al. 2002; Lawrence and Vandecar 2015), and mapping deforestation and understanding its proximate drivers are therefore crucial (DeFries et al. 2002). While much attention has been paid to the world’s humid tropical forests (Carr 2004; Geist and Lambin 2002; Hansen et al. 2013; Macedo et al. 2012), sub-humid and dry tropical forest and savannas remain understudied (Blackie et al. 2014; Lehmann 2010; Parr et al. 2014). This is particularly true for the dry forests and savannas of South America, which are currently undergoing a major wave of deforestation due to agricultural expansion (Aide et al. 2013), as well as agricultural intensification (Graesser et al. 2015), especially in the Cerrado (Brannstrom et al. 2008; Klink and Machado 2005), the Chiquitana (Müller et al. 2012) and the Chaco forests (Gasparri and Grau 2009; Vallejos et al. 2015).

Forest loss in these regions is mainly due to a globally growing demand for agricultural commodities, including for soybeans, maize and beef (Gasparri and le Polain de Waroux 2014; Kastner et al. 2012; Reenberg and Fenger 2011). As a result, tropical sub-humid and dry forests in South America are lost at alarming rates due to the expansion of both cattle ranching and soybean cultivation (Goldfarb and Zoomers 2013; Macedo et al. 2012; Reenberg and Fenger 2011). Yet, while area-wide information on deforestation are recently emerging (Vallejos et al. 2015), information on post-deforestation land uses remains unavailable for many of these regions. The latter is problematic in at least two ways. First, the environmental outcomes of deforestation differ markedly depending on post-deforestation land use. For example, carbon emissions are much larger when forest is converted to cropland than to pastures (Fujisaki et al. 2015; Houghton et al. 2012), and more biodiversity can persists in pastures compared to industrialized croplands (Carvalho et al. 2009; Jangid et al. 2008; Macchi et al. 2013; Mastrangelo and Gavin 2014; Medan et al. 2011). Second, deforestation may only be the first step in a sequence of land-use changes. For example, pastures in South America’s subtropical forest regions are increasingly being converted to cropland, especially in regions suitable for soybean cultivation (Brannstrom et al. 2008; Gasparri and Grau 2009; Müller et al. 2012). Similarly, while cattle stocking rates right after deforestation are often low, intensification of cattle grazing may take place leading to higher cattle density, changing management practices, and thus resulting in strong effects on ecosystem processes such as soil stability and carbon storage (Abril et al. 2005). Given that the environmental and societal outcomes of intensification processes can be substantial, understanding post-deforestation land-use change is important, but often hampered by a lack of consistent land-change data.

Moreover, there is increasing evidence that deforestation and post-deforestation land-use change processes may be spatially and temporarily linked (Gasparri et al. 2013; Gasparri and le Polain de Waroux 2014). Rising soybean prices relative to beef prices create incentives for converting pastures to cropland, which may lead to spillover effects in the form of pasture expansion into forests elsewhere (Gasparri and le Polain de Waroux 2014). Also, while soybean agriculture and cattle ranching have traditionally been associated with different groups of actors, large agribusiness enterprises increasingly tend to engage in both (Goldfarb and Zoomers 2013). As a result, soybean revenues from one area may allow actors to acquire land elsewhere, potentially amplifying deforestation rates (Gasparri and le Polain de Waroux 2014). These examples highlight the need to go beyond simple assessments of deforestation, and to consider post-deforestation land changes including intensification trends. This requires the joint use of remote sensing and agricultural statistics, which is now possible as the opening of the Landsat archives (Woodcock et al. 2008) and new algorithms (Griffiths et al. 2013b; Masek et al. 2006; Potapov et al. 2015) allow reconstructing deforestation and post-deforestation land change since 1984, and agricultural statistics are often available at least for a number of years.

The South American Chaco, a subtropical forest region in northern Argentina, Paraguay, and southeastern Bolivia, has recently emerged as a global deforestation hot spot (Hansen et al. 2013), driven by the expansion and intensification of cattle ranching and soybean cultivation (Grau and Aide 2008). Yet, few studies have assessed land-use changes in the Chaco, and most of them have focused on forest loss on the one hand, and the Dry Chaco only on the other (Vallejos et al. 2015). Moreover, most studies have assessed only the Argentinean Chaco (Boletta et al. 2006; Gasparri and Grau 2009; Gasparri et al. 2010; Hoyos et al. 2013; Volante et al. 2012;Zak et al. 2004, 2008), although land change in the Wet Chaco and the Bolivian and Paraguayan parts of the ecoregion has also been substantial (Caldas et al. 2015; Hansen et al. 2013; Killeen et al. 2007). Overall thus, our understanding of land-use processes for the environmentally diverse Chaco ecoregion remains incomplete.

Particularly Paraguay has been a deforestation hot spot lately (Baumann et al. 2016a; Hansen et al. 2013), but only a handful of studies have attempted to map land change there, and these studies also have a number of limitations. First, deforestation assessments in the Paraguayan Chaco have focused on the time period since 2001 only (Caldas et al. 2015; Hansen et al. 2013), although substantial deforestation occurred before (Huang et al. 2007, 2009). Second, existing studies have often relied on images from the moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) (Caldas et al. 2015; Clark et al. 2010) which may omit small-scale land changes. Finally, only one study has assessed the post-deforestation land uses and thus the proximate causes of forest loss. Using MODIS data, Graesser et al. (2015) showed that cropland expansion was lower than pasture expansion. Likewise, deforestation was high during the first years of the 2000s, but slowed down after 2007 (Graesser et al. 2015). However, no study has mapped post-deforestation dynamics and forest loss consistently and at fine scale for longer time periods.

Analyzing land change trajectories over longer time periods (i.e., until the mid-1980s) in Paraguay would be particularly interesting because important economic and policy changes happened in the early 2000s that likely impacted land-use change trends in major ways. This would thus allow to compare land-use change pattern prior and posterior to the economic and policy changes. Here, our goal was therefore to reconstruct land change since 1987 for the Paraguayan Chaco based on high-resolution satellite images and agricultural statistics. Specifically, we assessed the following research questions:

-

1.

What were the rates and spatial patterns of deforestation in the entire Paraguayan Chaco between 1987 and 2012?

-

2.

Which proximate causes led to deforestation and what were post-deforestation land-use/land-cover changes in the Paraguayan Chaco?

-

3.

Did pasture and cropland expansion result in decreasing or increasing land-use intensity?

Methods

Study area

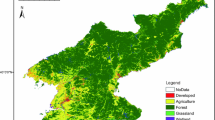

Our study area comprised the Paraguayan part of the Chaco region and consisted of the three most western departments (i.e., states) of the country: Alto Paraguay, Boquerón, and Villa Hayes (Fig. 1, Figure SI 1). Together, these three departments cover roughly 60% of Paraguay (243,000 km2). Topography in the region is mostly flat, and elevation increases gently from about 80 m in the very eastern part to approximately 400 m in the west (Jarvis et al. 2008). Mean annual temperatures in our study area are around 25 °C with decreasing temperatures from north to south (Fatecha 1989), and with high daily maximum temperatures (40 °C) occurring even during the winter. Rainfall occurs seasonally highly clustered, with most rainfall events between October and March (i.e., the summer months). The study region shows a strong rainfall gradient from east (~1300 mm/year) to west (~400 mm/year) (Vargas Gil 1988). As a result, the Paraguayan Chaco is further subdivided into the Dry Chaco and the Wet Chaco (Figure SI 1). The Wet Chaco has generally higher rainfall (900–1300 mm/year) compared to the Dry Chaco (400–900 mm/year) and is in addition more susceptible to heavy rainfall events and subsequent flooding (Vargas Gil 1988). The Paraguayan Chaco’s soils are dominated by eutric cambisols and orthic luvisols, often with a relatively shallow humus horizon of 20–25 cm, which is getting even shallower moving west (Buol 2007). The environmental conditions in the Chaco facilitate a very quick mineralization, resulting in soils that are generally fertile (Prado 1993).

Results of the land-use/land-cover classification. Presented are the overall change map for the entire time period (a) including three detail views (A1–A3), as well as the land-cover maps for each of the three years 1987 (B1), 2001 (B2) and 2012 (B3). c location of the study area in the Gran Chaco (gray area) and South America (for more details on the study are please see figure SI 1)

The original landscape of the Chaco was a mosaic of vegetation types composed of xerophilous to subxerophilous forests, intermingled with gallery forests, savannas and grasslands. This mosaic was generated by edaphic and climatic factors and fire with changes determined by the east–west rainfall pattern (Bucher 1982; Cabrera 1976). In the Dry Chaco, dry deciduous forest and thorn bush forests are dominating, whereas in the Wet Chaco riparian forests, palm forests combined with grasses, occasional shrubs and weeds are dominating together with woody shrub vegetation (Prado 1993). The most characteristic and economically important tree species are the ‘quebrachos’ belonging to the genera Schinopsis (S. balansae and S. lorentzii, ‘quebrachos colorados’) and Aspidosperma (A. quebracho, ‘quebracho blanco’). In the Wet Chaco, other common trees include ‘guayacán’ (Caesalpinia paraguariensis), ‘urunday’ (Astronium balansae), ‘palo lanza’ (Phyllostylon rhamnoides), while in the Dry Chaco other important trees includes ‘algarrobos’ (Prosopis spp.), ‘palo santo’ (Bulnesia sarmientoi) and ‘itín’ (Prosopis kuntzei). The shrub layer is dominated by species of Acacia, Mimosa, Prosopis and Celtis. The cacti, Opuntia and Cereus, grasses and bromeliads are abundant in the understory (Bucher 1982; Cabrera 1976; Glatzle 1999).

Historically, the Paraguayan Chaco was only sparsely inhabited by indigenous people who lived mainly from hunting and gathering (Seyler 1988). Colonization of the Chaco occurred late, and the first settlements in the central Dry Paraguayan Chaco were only established in the 1920s by Mennonite immigrants. By that time, land use in the Paraguayan Chaco was mostly subsistence agriculture with mainly crops and only some cattle ranching (Hamp and Tiefert 1989). Infrastructure development along with agricultural innovation led to substantial cropland expansion from the 1940s on, resulting in a doubling of the crop production between 1956 and 1981 (Fatecha 1989). Major crops were sorghum, cotton, groundnuts and cassava, mostly used as fodder in the cattle production. Cattle ranching focused originally on natural grasslands, mainly in the southwest of the Paraguayan Chaco, but expanded rapidly after 1950 into the Chaco’s forest. With increasing importance of cattle for export, cattle ranching expanded and transitioned from local, small-scale ranches toward large-scale farming (Fatecha 1989).

Mapping deforestation and its proximate drivers

We mapped deforestation and agricultural expansion in the Paraguayan Chaco using Landsat image composites for the years 1986/87 (1987 hereafter), 2000/2001 (2001) and 2011/2012 (2012). Landsat image composites represent mosaics of many Landsat images within a user-defined study area and time period. This is superior to the more traditional single-image approach for several reasons. By making use of the entire Landsat archives, multiple (preferably all) observations at each location of the study area are considered, which decreases the probability of obstructions by clouds and cloud shadows. Thus, an image composite typically provides a gapless and cloud-free coverage for any study area (Potapov et al. 2011, 2012), which in a single-image analysis is often not the case. Moreover, certain land-use change processes, such as the conversion from grasslands to cropland, are not always easily distinguishable in single images. For example, when crops are young they may look spectrally similar to grasses. Likewise, senescent crops (e.g., cereals) may spectrally resemble mature grasslands. Image composites can be created using imagery from different seasons and consecutive years, thereby allowing to make better use of phenology differences in target classes (Griffiths et al. 2013a). Finally, by considering all images over a study area, spectral metrics such as the mean or standard deviation reflectance can be calculated (so-called image metrics), which provide additional information about land-use classes and are powerful for better mapping land-use/land-cover change (Griffiths et al. 2013b).

Utilizing the entire Landsat archives, in our case a total of 1775 images from Landsat 4, 5 and 7 at a spatial resolution of 30 m requires streamlined preprocessing algorithms. We automatically corrected for atmospheric effects using the Landsat Ecosystem Disturbance Adaptive Processing System (LEDAPS) (Masek et al. 2006). Similarly, we automatically masked out all clouds and cloud shadows using the Fmask algorithm (Zhu and Woodcock 2012). Once preprocessing was completed, we generated for each of the three target years (a) a best-observation composite centered around day of year 365 (December 31), (b) three image metrics for each of the six multispectral bands from Landsat (mean, standard deviation and range) and (c) the sum of the near-infrared (NIR) and shortwave-infrared (SWIR) bands normalized over the number of clear observations for further information on vegetation characteristics of different land-cover types (Griffiths et al. 2013b). These composites and metrics served as the basis for our classification.

We classified the four land-cover classes ‘forest', ‘grassland’, ‘cropland’ and ‘other’ (representing water bodies, urban areas, roads and bare soil) for each of the target years individually. We generated training data for these classes by visually interpreting the Landsat image composites on conjunction with high-resolution images in Google Earth (Baumann et al. 2015; Clark and Aide 2011; Cohen et al. 2010; Foody and Mathur 2004). Therefore, the forest class contained dense forests, as well as other vegetation formations dominated by woody vegetation (e.g., thorn bush forests, shrublands) without indication of grazing activities. Grasslands contained natural grasslands (e.g., along rivers), savannahs and, predominantly, pastures, and these areas were considered also in case of temporary inundations. The grassland class could contain individual trees in the landscape, though without any shrubby undergrowth. The cropland class was characterized by annual crops that were cultivated in highly managed agricultural systems, most visible through plow lines in high-resolution imagery, and very bright areas in the Landsat composites (Figure SI 2).

Using these training data, we classified the image composites using a random forest classifier (Breiman 2001; Waske et al. 2012). Random forests belong to the group of machine learning algorithms and use ensembles of decision trees to achieve the best possible class separation. Once individual land-use/land-cover maps were available, we assessed the changes among our target years by generating a land-use change map applying post-classification comparison (Coppin et al. 2004; Lu et al. 2004). To remove salt-and-pepper patterns, which mainly were the result of misclassifications, we applied a minimum mapping unit of 0.54 ha (i.e., six Landsat pixels). Lastly, we masked non-realistic classes (e.g., a cropland to forest conversion) which were remnants from the post-classification comparison and labeled these areas as ‘unclassified’ (less than 3% of the area).

To validate our maps, we performed two independent accuracy assessments. First, we assessed the accuracy of each of the three target-year classifications by generating a stratified random sample of 550 points. For each of the points, we checked the correct class assignment based on the interpretation of the Landsat composites and the Google Earth imagery. We generated an error matrix, calculated the overall accuracy as well as class-wise accuracies (Foody 2002, 2008). We also corrected for potential sampling bias in our validation dataset (Stehman 2013) and calculated confidence intervals around the area estimates of each of our single-year maps (Olofsson et al. 2013, 2014). Second, we validated our change map for the full time period (1987–2012) by generating a second stratified random sample of 50 points per class. Again, we checked each point for its correct class assignment, but had to consider the multitemporal nature of the validation points. For example, a point that was sampled into the class ‘forest to grassland 2001–2012’ had to be identified in forest area in the 1987 and 2001 composites and grassland area in 2012. We evaluated each of the validation points in this way, and generated an error matrix, and calculated the overall accuracy and the kappa statistic of the map, as well as user’s and producer’s accuracies for the individual classes.

Once our final change map was available, we assessed the spatial–temporal dynamics of deforestation and cropland and grassland expansion. To do so, we summarized the areas of forest, grassland and cropland at each of our three time periods, and calculated the deforestation rates (%), the proportion of croplands that were previously grasslands (%), as well as the absolute changes in grazing lands (km2). We did this for the two time periods (i.e., 1987–2000 and 2001–2012) individually and for the entire time period. The deforestation rate was calculated as the area of forest loss during a given period (e.g., 1987–2000) relative to the forest area at the beginning of that period (i.e., 1987). We did this for the study region as a whole, as well as for the three departments individually. We further summarized areas and calculated rates of change for the Dry and the Wet Chaco separately.

Relating agricultural expansion to the intensity of cattle production

To assess whether the expansion of cropland and grassland was accompanied by changes in agricultural intensity, we related our land-change estimates to available official statistics for cattle production in our three departments. Specifically, we gathered information of cattle heads for the years 1990, 2001 and 2012 (Republica del Paraguay 2009) and related these numbers to the estimates of grassland area for the three years from our satellite analysis, as the vast majority of grasslands in the study area are used for cattle ranching (Campos-Krauer and Wisely 2011).

Results

Our classifications for the target years resulted in reliable land-use/land-cover maps (Fig. 1B1–B3) with overall accuracies of the individual maps of 93.2%, 94.7% and 94.9% for 1987, 2001 and 2012, respectively (Table SI-1). Producer’s accuracies were consistently high for all three classifications, especially for the forest, grassland and other class. Producer’s accuracies were also generally high, with the exception of cropland in 1987 (Table SI-1). Validating our change map (Fig. 1A) showed that our change assessment was of high quality as well, reaching overall accuracies of 86.16% (Table SI-2). Class-wise accuracies in our change map were highest for the forest and grassland class, as well as for the transition classes between forests and grasslands (Table SI-2).

Our land-use/land-cover maps revealed that in 2012 large parts of our study area were still forested (58%), but we also found widespread grasslands (34%). Croplands only covered a very smaller portion of our study area (0.5%). However, compared to 1987, the current landscape had been transforming profoundly: 43,915 km2 of forest were deforested in the 26 years we studied, equaling more than 27% of all forests in the Paraguayan Chaco in 1987 and a deforestation rate of roughly 1.0% per year (Fig. 2A1, Table 1). However, the speed of deforestation varied substantially between the two time periods: Whereas ~15,000 km2 were lost between 1987 and 2000 (equaling a total deforestation rate of 9.1% or 0.6% per year), deforestation increased dramatically between 2001 and 2012, when 29,000 km2 of forest were converted, equaling a ~18% loss or 1.5% per year (Fig. 2A2). Deforestation rates were higher in the Wet Chaco, where ~29.5% of natural forests were deforested in 1987–2012, compared to ~26.5% in the Dry Chaco (Fig. 2A2). The Dry Chaco showed a higher deforestation rate than the Wet Chaco (18.5 vs. 14.5%) in 2001–2012, while this was the opposite in 1987–2000 (8 vs. 14%, Fig. 2A2).

Results of the land-use/land-cover classification, summarized by province (Alto Paraguay, Boqueron, Presidente Hayes) and region (entire study region, Dry Chaco, Wet Chaco). Presented are the deforestation rates (A1, A2), changes in grassland areas (B1, B2) and the ratio of new croplands from previous grasslands (i.e., intensification) to new croplands from forests. All three measures are presented for the two time periods (1987–2001 and 2001–2012) individually as well as for the entire study period (1987–2012). A1, B1, C1 show the measures summarized at the provincial level; A2, B2, C2 show each measure for the entire study area and split up individually by the Dry and the Wet Chaco

Deforestation also varied substantially between the three departments: deforestation rates between 1987 and 2012 where highest in Boqueron and Presidente Hayes (30.5% and 29.5%, respectively) and slightly lower in Alto Paraguay (22%, Fig. 2A1). Deforestation rates also varied from departments to departments over time. For example, while the deforestation rate in Presidente Hayes was constant in the two time periods (i.e., 14.5%), the other two provinces showed much lower deforestation rates between 1987 and 2000 (6.5% for Alto Paraguay, and 9.3% in Boqueron), but higher deforestation rates between 2001 and 2012 (15.5% and 21.8% for Alto Paraguay and Boqueron, respectively, Fig. 2A1).

Grassland expansion was by far the most important post-deforestation land cover/land use in the Paraguayan Chaco. New grasslands increased between 1987 and 2012 by ~21,000 km2 (~34.5% or 1.2% per year). The vast majority of new grasslands were established between 2001 and 2012 (+32.7%), whereas between 1987 and 2000 grasslands increased only by 1.7% (Fig. 2B2). The majority of the new grasslands occurred in the department Boqueron (~70%), whereas in Presidente Hayes, grassland areas remained overall rather stable (−0.2% and −0.6%). Areas located in the Dry Chaco accounted for the entire net increase of grassland areas (21,150 km2), whereas we found a net decrease of grasslands in the Wet Chaco (−2200 km2, Fig. 2B1). Overall, grassland was the dominant post-deforestation land cover in all departments, though in Boqueron the ratio was slightly lower (97.7%) compared to Alto Paraguay and Presidente Hayes (both above 99.5%). Further, between 2001 and 2012 the ratio was lower than in 1987–2001 in the three departments: Alto Paraguay (99.9% and 99.0%), Boqueron (99.6% and 96.9%) and Presidente Hayes (99.9% and 99.3%).

Cropland expansion played only a minor role in driving deforestation. By 2012, only 1330 km2 of our study area were used for cropland, equaling 0.5%. Between 1987 and 2000 we found a net decrease of cropland area (from 293 to 224 km2), whereas during the second period croplands net increased by 1106 km2. Of the newly established croplands, 47% came from deforestation (602 km2), and 53% (676 km2) from converting grassland areas into cropland. In absolute numbers, the department of Boqueron showed a remarkable increase in cropland (+975 km2), accounting for nearly 75% of the overall increase in cropland. When tracing the source of the new croplands (i.e., whether it came from grassland or from forest), however, the pattern strongly diverge. In Presidente Hayes, the most eastern department of our study area, nearly 85% of the new croplands came from grasslands (196 km2) whereas this proportion was much lower in Boqueron (48%) and Alto Paraguay (24.5%, Fig. 2C1). For the Wet Chaco, this proportion increases to over 87%, whereas in the Dry Chaco only 49% of new croplands came from grasslands (Fig. 2C2).

Relating the changes in grassland to cattle production statistics provides further insights into the intensity of ranching. Cattle numbers in the Paraguayan Chaco increased between 1987 and 2012 from 3,208,000 to more than 5,235,000 heads (equaling a 63% increase) and thus at a much higher rate than the increase in grassland area (+34.5% for the same time period, equaling ~21,000 km2). Comparing among time periods, however, revealed that cattle heads actually decreased by ~250,000 (−9%) between 1987 and 2000, although grassland areas through deforestation had increased slightly during that time (911 km2 or +1.5%), overall resulting in a decrease of cattle density from 53 to 47 heads/km2. This pattern reversed completely during the second time period, when our results suggest a strong increase in both, cattle numbers (2,300,000) and grassland area (20,000 km2, Fig. 3), yet with a much stronger increase in cattle heads compared to grassland area (+78 vs. +32%), resulting in a cattle density of ~64.5 heads/km2.

Relationship between grassland area and the number of cattle heads produced in each of the three time points of our analysis (1987, 2001, 2012). The amount of grassland areas came from our land-use/land-cover change analysis, information about cattle heads from the statistical census of Paraguay (Republica del Paraguay 2009). The relationship is presented for the study area as a whole and for each province individually. Please note the differences in the axis labels

We also found interesting differences among the three departments we assessed. In Alto Paraguay, the largest department in our study area, cattle production and grassland area mirrored the trends we found for the entire study region, with a slight decrease in cattle heads during the first period (by 0.03%, equaling −11,765 cattle heads) and a strong increased by 914,000 heads after 2001 (i.e., +300%). In Boqueron, the number of cattle heads and grassland area increased in both time periods but cattle numbers increased more strongly compared to grassland areas (+116 vs. 18% for 1987–2000, and +112 vs. 85% for 2001–2012). In Presidente Hayes, grassland areas were generally less widespread, and decreased in both time periods (~1500 km2 (−4%) 1987–2000 and ~250 km2 (−0.1%) 2001–2012, while cattle heads decreased only in 1987–2000 (−620,000, equaling −23%), but increased in 2000–2012 (630,000, +31%; Fig. 3).

Discussion

South America’s subtropical dry forests and savannas are among the world’s most dynamic deforestation frontiers (Aide et al. 2013; Hansen et al. 2013), but compared to the humid tropics, these frontiers remain underresearched. This is particularly so regarding the proximate drivers of deforestation and land-use changes following initial deforestation. Focusing on the entire Paraguayan Chaco, we highlight the drastic forest conversions that have been taking place there since 1987, with almost one-third of the forest converting to agriculture (i.e., pastures or croplands). Deforestation rates more than doubled between 2001 and 2012 compared to 1987–2000, likely at least in part due to leakage effects following a deforestation ban in the Paraguayan Atlantic Forests in 2004 (World Wildlife Fund 2015). As most forests were converted to grasslands, pasture for cattle ranching expansion appears to be the most dominant proximate cause of deforestation, whereas cropland expansion only played a minor role in the Wet Chaco. Interestingly, despite the increasing pasture areas in the Paraguayan Chaco between 1987 and 2000, cattle numbers decreased during this time, but then increased strongly after 2001. This suggests the Paraguayan Chaco underwent an amplification period during the 1990s, where pasture-to-soybean conversions elsewhere allowed ranchers to convert forestland to pastures in the Chaco. This period was followed by an intensification of ranching after 2001. In addition, deforestation rates showed spatial–temporal pattern that indicate a moving deforestation frontier from east to west of our study area. This makes the Paraguayan Chaco, a region of unique biodiversity and with substantial carbon stocks, a highly dynamic deforestation frontier, which is worrisome given the currently relatively weak nature protection and land-use planning.

A few studies have attempted to map forest loss in the Paraguayan Chaco (Caldas et al. 2015; Clark et al. 2010; Huang et al. 2009), but our study extends on previous work in four important ways: (a) by covering almost 35 years of land-use change, extending back to the 1980s, (b) by mapping land-use change consistently at high spatial resolution based on Landsat image composites, (c) by covering the entire Paraguayan Chaco, including both the Wet and the Dry Chaco and (d) by differentiating post-deforestation land uses. Our results concur with earlier studies in suggesting that deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco has been dramatic and has been intensifying lately. More than 27% of the natural forest of the Chaco in Paraguay was lost between 1987 and 2012, at rates similar to the most rapid deforestation frontiers in the humid tropics (Barona et al. 2010; Carlson et al. 2013; Macedo et al. 2012). Despite these rapid losses, the Chaco has been largely under the radar of most conservation organization and public policy debates as exemplified by the very sparse network of protected areas in the Paraguayan Chaco (The Nature Conservancy 2005). Conservation and sustainable land-use planning to better balance agriculture and the conservation of natural ecosystems and their biodiversity is urgently needed (Mastrangelo and Gavin 2012; Polasky et al. 2008).

Deforestation rates were much higher in 2001–2012 compared to 1987–2000. This may be, on one hand, a consequence of rising global agricultural commodity prices and an increasing integration of Paraguay into the world market (Kastner et al. 2012; Zak et al. 2008) which both resulted in major increases in revenues from agriculture and thus high incentives to expand and intensify agriculture. On the other hand, high forest loss rates in the 2000s may be at least partially a result of land scarcity and leakage. Historically, the Atlantic Forests of Paraguay showed very high deforestation rates (Huang et al. 2007, 2009), and in 2004, a Forest Conversion Moratorium for the Atlantic Forests was implemented. With most forests already converted in the Atlantic forest and the deforestation ban in place, the Chaco forests have likely absorbed agricultural expansion pressure.

Deforestation also differed substantially between the three departments of our study region (Alto Paraguay, Boqueron and Presidente Hayes), with particularly the Dry Chaco showing much higher deforestation rates between 2001 and 2012 compared to 1987–2000, when the Wet Chaco had higher conversion rates. Most deforestation after 2001 occurred in the western most provinces, whereas in the department of Presidente Hayes, which is closer to the Atlantic Forests, deforestation rates were high before, but not after 2001. These findings provide further evidence for a progressing deforestation frontier, and land conversion pressure originating from eastern Paraguay, possibly tied to the Forest Moratorium in the Atlantic Forests.

Grasslands were the dominating post-deforestation land use and assuming that these new grasslands represent pastures, pasture expansion was by far the leading proximate cause of deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco. In some areas in the Dry Chaco, rainfall may be too variable to allow for rain-fed soybean cultivation given current soybean strains. However, a number of factors suggest that pasture expansion in the Paraguayan Chaco may be indirectly connected to soybean expansion elsewhere. First, converting pastures into cropland is generally less capital intensive compared to converting forests into cropland. Soybean cultivation may thus happen mainly on pastures away from the deforestation frontier (and thus closer to markets), leading to a displacement of ranchers. As frontier forestland is typically cheaper than pasture land closer to markets, more deforestation and pasture expansion than soybean expansion can happen, a process that has been termed amplification (Gasparri and le Polain de Waroux 2014). Displacement and amplification are particularly likely to happen in systems where agricultural actors engage in both soybean cultivation and ranching, thus leading to coupled land-use changes (Barona et al. 2010; Gasparri and le Polain de Waroux 2014; Morton et al. 2006).

The Paraguayan Chaco appears to be a prime example of a region characterized by a coupling of soybean and pasture cultivations. Following the Forest Moratorium in the Atlantic Forests, pastures were increasingly converted into croplands (World Wildlife Fund 2015), leading to a displacement of ranching into the Paraguayan Chaco where ranchers sold their land. Likewise, agricultural actors acquired large tracts of land in the Chaco for future expansion and may have converted to pastures in fear of a potential future deforestation ban in the Paraguayan Chaco as well. Moreover, the Paraguayan Chaco may be linked to other regions outside Paraguay in similar dynamics. For example, Uruguayan farmers are rapidly acquiring pasture land in Paraguay to reinvest revenues they received from selling their land to Argentine soybean producers (Bertello 2008). This happens to the extent that already 12.5% of Paraguayan pastures are owned by Uruguayan farmers (Gonzales 2013). Thus, while pasture expansion seems to be the most dominant proximate cause of deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco, the soybean economy appears to be the dominant underlying cause of deforestation, similar to the Amazon (Barona et al. 2010) and the Argentine Chaco (Gasparri et al. 2013).

Comparing pasture area changes and cattle heads provides further evidence for an amplification phase, especially during the 1990s when cattle heads decreased while pasture area increased slightly. Contrary, after 2001 the Paraguayan Chaco appears to having entered an intensification phase, with a much stronger increase in cattle heads than in pasture area (despite much pasture expansion). Besides growing world market prices for agricultural commodities, technological innovation may be another reason for this intensification process. For example, Paraguayan ranchers have shifted toward using highly productive, exotic grasses like Gatton panic (Panicum maximun) and Buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) (Cabrera et al. 2001; Hecht 1975; Quinlan et al. 1980) which are reported to increase cattle productivity up to ten times (Ramirez and Laneri 1989). This intensification process did not happen uniformly across the three departments, but was more widespread in Presidente Hayes, and much less common in Alto Paraguay. The nucleus for these deforestation and intensification processes was primarily concentrated around the town of Filadelfia in the department of Boqueron, where the land ownership structure has been changed substantially during the past decades (Baumann et al. 2016b; Vidal 2010). Historically, Filadelfia is a Mennonite colony with traditional farming practices (Dana and Dana 2007). However, with increasing revenues from agriculture and comparatively low land prices and weak enforcement of forest protection legislations, production techniques have substantially changed: Today, only a few large Mennonite families operate as cooperative farm groups and have bought around 2 million hectares of land in the Chaco, which they mostly deforested for pastures during the past years, thus massively driving deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco (Vidal 2010). Overall thus, our results suggest that Paraguay is currently experiencing an intensification phase in its livestock system, potentially linked to a merging scarcity of land available for conversion in some parts of the country.

A few uncertainties in our analysis need mentioning. First, our mapping strategy does not identify alternating land uses (e.g., sequences of crop production and cattle), but such alternating sequences appear unlikely for the Paraguayan Chaco. Second, by focusing on two-year windows, some land-use changes may have been missed or labeled incorrectly. For example, forests converted to pastures may look like cropland in the first year, as all native vegetation is removed and grasses are implanted. Third, limited image availability for the first year of our analysis may have caused some overestimation of pastures for that year, and as such may have resulted in rather conservative estimates of pasture expansion during the first period of our analysis. Fourth, as in any remote sensing analyses, we mapped land cover and indirectly infer knowledge about land use (and land-use change). For example, we assumed all new grasslands to constitute pastures, an assumption strongly supported by high-resolution imagery, field visits and the literature (Campos-Krauer and Wisely 2011). However, we cannot rule out that some of the new grasslands are ungrazed (e.g., in the case of forest fires). Similarly, we assume all grasslands in 1987 to represent pastures, and these grasslands include natural grasslands. Most grasslands in the Chaco were indeed grazed for long periods, but some uncertainty regarding the exact pasture extent in 1987 remains. If not all 1987-grasslands were grazed, this would mean that grazing intensity decreased even more strongly in 1987–2000, thus providing further evidence for the amplification phase we found. Fifth, our cropland class for the year 1987 is less accurate than in the other years resulting in an underestimation of cropland area in 1987. This, however, means that cropland subsequently increased even less strong, thus further underpinning the importance of pastures. Lastly, our consideration of rather broad land-cover classes may result in overlooking dynamics within these classes, for example the degradation of forests or the loss of trees in savannas.

The Latin American dry forests are among the world’s most active deforestation frontiers, but our understanding of the rates and patterns of deforestation, and which proximate causes lead to deforestation remains limited. Focusing on the Paraguayan Chaco, we found that deforestation rates in the subtropical forests were high and accelerated during the past 15 years. The vast majority of deforestation was for pasture expansion, which was the main proximate cause of deforestation, particularly in the Dry Chaco. Given that most of the produced meat is exported, and that some pasture expansion likely was due to export-oriented soybean production elsewhere in Paraguay, and given rising commodity prices and global demand for these agricultural commodities, the land-change trends we found will likely continue in the absence of stronger land-use planning and regulation. Paraguay’s forests, a decade after a deforestation ban has been implemented in the Atlantic Forest, continue to be under immense conversion pressure, which is worrisome given their unique biodiversity and substantial carbon stocks.

References

Abril A, Barttfeld P, Bucher EH (2005) The effect of fire and overgrazing disturbes on soil carbon balance in the Dry Chaco forest. For Ecol Manag 206:399–405. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2004.11.014

Aide TM et al (2013) Deforestation and reforestation of Latin America and the Caribbean (2001–2010). Biotropica 45:262–271. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2012.00908.x

Blackie R et al (2014) Tropical dry forests: The state of global knowledge and recommendations for future research. In: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Bogor, Indonesia. p. 30. doi:10.17528/cifor/004408

Barona E, Ramankutty N, Hyman G, Coomes OT (2010) The role of pasture and soybean in deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon. Environ Res Lett. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/5/2/024002

Baumann M, Radeloff VC, Avedian V, Kuemmerle T (2015) Land-use change in the Caucasus during and after the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Reg Environ Change 15:1703–1716. doi:10.1007/s10113-014-0728-3

Baumann M, Gasparri I, Piquer-Rodríguez M, Gavier Pizarro G, Griffiths P, Hostert P, Kuemmerle T (2016a) Carbon emissions from agricultural expansion and intensification in the Chaco. Glob Change Biol. doi:10.1111/gcb.13521

Baumann M, Piquer-Rodríguez M, Fehlenberg V, Gavier Pizarro G, Kuemmerle T (2016b) Land-use competition in the South American Chaco. In: Niewöhner J et al (eds) Land use competition: ecological, economic and social perspectives. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 215–229. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33628-2_13

Bertello F (2008) Cada vez más productores argentinos van a sembrar soja a Uruguay. http://www.lanacion.com.ar/992652-cada-vez-mas-productores-argentinos-van-a-sembrar-soja-a-uruguay. Accessed 22 Nov 2016

Boletta PE, Ravelo AC, Planchuelo AM, Grilli M (2006) Assessing deforestation in the Argentine Chaco. For Ecol Manag 228:108–114. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.02.045

Brannstrom C, Jepson W, Filippi AM, Redo D, Xu ZW, Ganesh S (2008) Land change in the Brazilian Savanna (Cerrado), 1986–2002: comparative analysis and implications for land-use policy. Land Use Policy 25:579–595. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.11.008

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45:5–32. doi:10.1023/a:1010933404324

Bucher EH (1982) Chaco and Caatinga—South American arid Savannas. In: Huntley BJ, Walker BH (eds) Woodlands and tickets. Springer, Berlin, pp 48–80

Buol SW (2007) Soils. In: Veblen TT, Young KR, Orme AR (eds) The physical geography of South America. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 101–111

Cabrera AL (1976) Regiones Fitogeograficas de Argentina. ACME, Buenos Aires

Cabrera AJN, Stosiek D, Glatzle A, Shelton HM, Schultze-Kraft R (2001) Liveweight gains of steers at different stocking rates on monospecific Gatton panic and Estrella grass pastures in the Chaco Central region of Paraguay. Trop Grassl 35:186–192

Caldas MM, Goodin D, Sherwood S, Campos Krauer JM, Wisely SM (2015) Land-cover change in the Paraguayan Chaco: 2000–2011. J Land Use Sci 10:1–18. doi:10.1080/1747423X.2013.807314

Campos-Krauer JM, Wisely SM (2011) Deforestation and cattle ranching drive rapid range expansion of capybara in the Gran Chaco ecosystem. Glob Change Biol 17:206–218. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02193.x

Carlson KM, Curran LM, Asner GP, Pittman AM, Trigg SN, Adeney JM (2013) Carbon emissions from forest conversion by Kalimantan oil palm plantations. Nat Clim Change 3:283–287. doi:10.1038/Nclimate1702

Carr DL (2004) Proximate population factors and deforestation in tropical agricultural frontiers. Popul Environ 25:585–612

Carvalho FMV, De Marco P, Ferreira LG (2009) The Cerrado into-pieces: habitat fragmentation as a function of landscape use in the savannas of central Brazil. Biol Conserv 142:1392–1403. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.01.031

Clark ML, Aide TM (2011) Virtual Interpretation of Earth Web-Interface Tool (VIEW-IT) for collecting land-use/land-cover reference data. Remote Sens 3:601–620

Clark ML, Aide TM, Grau HR, Riner G (2010) A scalable approach to mapping annual land cover at 250 m using MODIS time series data: a case study in the Dry Chaco ecoregion of South America. Remote Sens Environ 114:2816–2832. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2010.07.001

Cohen WB, Yang ZG, Kennedy R (2010) Detecting trends in forest disturbance and recovery using yearly Landsat time series: 2. TimeSync—tools for calibration and validation. Remote Sens Environ 114:2911–2924. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2010.07.010

Coppin P, Jonckheere I, Nackaerts K, Muys B, Lambin E (2004) Digital change detection methods in ecosystem monitoring: a review. Int J Remote Sens 25:1565–1596

Dana L-P, Dana TE (2007) Collective entrepreneurship in a mennonite community in Paraguay. Latin Am Bus Rev 8:82–97

DeFries RS, Houghton RA, Hansen MC, Field CB, Skole D, Townshend J (2002) Carbon emissions from tropical deforestation and regrowth based on satellite observations for the 1980s and 1990s. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:14256–14261

Fatecha A (1989) Present and potential area for agricultural use in the arid Chaco of Paraguay. In: Hamp M, Tiefert MA (eds) Agricultural production under semi-arid conditions with special reference to the Paraguayan Chaco: strategies and appropriate technologies. Food and Agriculture Development Centre, Feldafing, pp 26–49

Foody GM (2002) Status of land cover classification accuracy assessment. Remote Sens Environ 80:185–201

Foody GM (2008) Harshness in image classification accuracy assessment. Int J Remote Sens 29:3137–3158. doi:10.1080/01431160701442120

Foody GM, Mathur A (2004) Toward intelligent training of supervised image classifications: directing training data acquisition for SVM classification. Remote Sens Environ 93:107–117. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2004.06.017

Fujisaki K, Perrin AS, Desjardins T, Bernoux M, Balbino LC, Brossard M (2015) From forest to cropland and pasture systems: a critical review of soil organic carbon stocks changes in Amazonia. Glob Change Biol 21:2773–2786. doi:10.1111/gcb.12906

Gasparri NI, Grau HR (2009) Deforestation and fragmentation of Chaco dry forest in NW Argentina (1972–2007). For Ecol Manag 258:913–921. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2009.02.024

Gasparri NI, le Polain de Waroux Y (2014) The coupling of South American soybean and cattle production frontiers: new challenges for conservation policy and land change science. Conserv Lett 8:290–298. doi:10.1111/conl.12121

Gasparri NI, Parmuchi MG, Bono J, Karszenbaum H, Montenegro CL (2010) Assessing multi-temporal Landsat 7 ETM + images for estimating above-ground biomass in subtropical dry forests of Argentina. J Arid Environ 74:1262–1270. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.04.007

Gasparri NI, Grau HR, Gutiérrez Angonese J (2013) Linkages between soybean and neotropical deforestation: coupling and transient decoupling dynamics in a multi-decadal analysis. Glob Environ Change 23:1605–1614. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.09.007

Geist HJ, Lambin EF (2002) Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation. Bioscience 52:143–150

Glatzle A (1999) Compendio para el Manejo de Pasturas en el Chaco. Editorial El Lector. Asuncion, Paraguay, pp 214

Goldfarb L, Zoomers A (2013) The drivers behind the rapid expansion of genetically modified soya production into the Chaco Region of Argentina. In: Fang Z (ed) Biofuels—economy, environment and sustainability. InTech Publisher, Rijeka, pp 73–95. doi:10.5772/53447

Gonzales D (2013) Uruguayos ya explotan el 12,5% de las tierras ganaderas en Paraguay. http://www.ultimahora.com/uruguayos-ya-explotan-el-125-las-tierras-ganaderas-paraguay-n599977.html. Accessed 22 Nov 2016

Goodale CL et al (2002) Forest carbon sinks in the Northern Hemisphere. Ecol Appl 12:891–899

Graesser J, Aide M, Grau R, Ramankutty N (2015) Cropland/pastureland dynamics and the slowdown of deforestation in Latin America. Environ Res Lett 10:034017

Grau HR, Aide M (2008) Globalization and land-use transitions in Latin America. Ecol Soc 13(2):16. doi:10.5751/ES-02559-130216

Griffiths P, Müller D, Kuemmerle T, Hostert P (2013a) Agricultural land change in the Carpathian ecoregion after the breakdown of socialism and expansion of the European Union. Environ Res Lett 8:045024

Griffiths P, van der Linden S, Kuemmerle T, Hostert P (2013b) A pixel-based landsat compositing algorithm for large area land cover mapping. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. doi:10.1109/jstars.2012.2228167

Hamp M, Tiefert MA (1989) Agricultural production under semi-arid conditions with special reference to the Paraguayan Chaco: strategies and appropriate technologies. In: Proceedings of a German/Israel/Paraguayan workshop in Kibbutz Shefayim Guest House (near Tel-Aviv) Israel, 1–7 Dec 1988. Food and Agriculture Development Centre

Hansen MC et al (2013) High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342:850–853. doi:10.1126/science.1244693

Hecht A (1975) The Agricultural economy of the mennonite settlers in Paraguay. Growth Change 6:14–23. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2257.1975.tb00808.x

Houghton RA et al (2012) Carbon emissions from land use and land-cover change. Biogeosciences 9:5125–5142. doi:10.5194/bg-9-5125-2012

Hoyos LE, Cingolani AM, Zak MR, Vaieretti MV, Gorla DE, Cabido MR (2013) Deforestation and precipitation patterns in the arid Chaco forests of central Argentina. Appl Veg Sci 16:260–271. doi:10.1111/j.1654-109X.2012.01218.x

Huang CQ et al (2007) Rapid loss of Paraguay’s Atlantic forest and the status of protected areas—a Landsat assessment. Remote Sens Environ 106:460–466. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2006.09.016

Huang CQ et al (2009) Assessment of Paraguay’s forest cover change using Landsat observations. Global Planet Change 67:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2008.12.009

Jangid K et al (2008) Relative impacts of land-use, management intensity and fertilization upon soil microbial community structure in agricultural systems. Soil Biol Biochem 40:2843–2853. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.07.030

Jarvis A, Reuter HI, Nelson A, Guevara E (2008) Hole-filled seamless SRTM data V4. International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org

Kastner T, Rivas MJI, Koch W, Nonhebel S (2012) Global changes in diets and the consequences for land requirements for food. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:6868–6872. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117054109

Killeen TJ, Calderon V, Soria L, Quezada B, Steininger MK, Harper G, Solórzano LA, Tucker CJ (2007) Ambio. J Hum Environ 36(7):600–606. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[600:Tyolci]2.0.Co;2

Klink CA, Machado RB (2005) Conservation of the Brazilian Cerrado. Conserv Biol 19:707–713. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00702.x

Lawrence D, Vandecar K (2015) Effects of tropical deforestation on climate and agriculture. Nat Clim Change 5:27–36. doi:10.1038/Nclimate2430

Lehmann CER (2010) Savannas need protection. Science 327:642–643. doi:10.1126/science.327.5966.642-c

Lu D, Mausel P, Brondizio E, Moran E (2004) Change detection techniques. Int J Remote Sens 25:2365–2407

Macchi L, Grau HR, Zelaya PV, Marinaro S (2013) Trade-offs between land use intensity and avian biodiversity in the dry Chaco of Argentina: a tale of two gradients. Agric Ecosyst Environ 174:11–20. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2013.04.011

Macedo MN, DeFries RS, Morton DC, Stickler CM, Galford GL, Shimabukuro YE (2012) Decoupling of deforestation and soy production in the southern Amazon during the late 2000s. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:1341–1346. doi:10.1073/pnas.1111374109

Masek JG et al (2006) A Landsat surface reflectance dataset for North America, 1990–2000. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett 3:68–72

Mastrangelo ME, Gavin MC (2012) Trade-offs between cattle production and bird conservation in an agricultural frontier of the Gran Chaco of Argentina. Conserv Biol 26:1040–1051. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01904.x

Mastrangelo ME, Gavin MC (2014) Impacts of agricultural intensification on avian richness at multiple scales in Dry Chaco forests. Biol Conserv 179:63–71. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2014.08.020

Medan D, Torretta JP, Hodara K, de la Fuente EB, Montaldo NH (2011) Effects of agriculture expansion and intensification on the vertebrate and invertebrate diversity in the Pampas of Argentina. Biodivers Conserv 20:3077–3100. doi:10.1007/s10531-011-0118-9

Morton DC et al (2006) Cropland expansion changes deforestation dynamics in the southern Brazilian Amazon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:14637–14641. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606377103

Müller R, Müller D, Schierhorn F, Gerold G, Pacheco P (2012) Proximate causes of deforestation in the Bolivian lowlands: an analysis of spatial dynamics. Reg Environ Change 12:445–459. doi:10.1007/s10113-011-0259-0

Olofsson P, Foody GM, Stehman SV, Woodcock CE (2013) Making better use of accuracy data in land change studies: estimating accuracy and area and quantifying uncertainty using stratified estimation. Remote Sens Environ 129:122–131. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2012.10.031

Olofsson P, Foody GM, Herold M, Stehman SV, Woodcock CE, Wulder MA (2014) Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens Environ 148:42–57. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2014.02.015

Parr CL, Lehmann CER, Bond WJ, Hoffmann WA, Andersen AN (2014) Tropical grassy biomes: misunderstood, neglected, and under threat. Trends Ecol Evol 29:205–213. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.02.004

Polasky S et al (2008) Where to put things? Spatial land management to sustain biodiversity and economic returns. Biol Conserv 141:1505–1524. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.03.022

Potapov P, Turubanova S, Hansen MC (2011) Regional-scale boreal forest cover and change mapping using Landsat data composites for European Russia. Remote Sens Environ 115:548–561

Potapov PV et al (2012) Quantifying forest cover loss in Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2000–2010, with Landsat ETM + data. Remote Sens Environ 122:106–116. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2011.08.027

Potapov PV, Turubanova SA, Tyukavina A, Krylov AM, McCarty JL, Radeloff VC, Hansen MC (2015) Eastern Europe’s forest cover dynamics from 1985 to 2012 quantified from the full Landsat archive. Remote Sens Environ 159:28–43. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2014.11.027

Prado DE (1993) What is the Gran Chaco vegetation in South America? I. A review: contribution to the study of flora and vegetation of the Chaco. V Candollea 48:145–172

Quinlan JF, Scarone CA, Laneri JL (1980) Cattle tick identification and seasonal-variation in infestation rates in Paraguay. Trop Anim Health Prod 12:259–264. doi:10.1007/Bf02236626

Ramirez EG, Laneri JL (1989) Fodder and feeding of cattle in the Paraguayan Chaco. In: Hamp M, Tiefert MA (eds) Agricultural production under semi-arid conditions with special reference to the Paraguayan Chaco: strategies and appropriate technologies. Food and Agriculture Development Centre, Feldafing, pp 139–148

Reenberg A, Fenger NA (2011) Globalizing land use transitions: the soybean acceleration. Geogr Tidsskr-Den 111:85–92

Republica del Paraguay (2009) Censo Agropecuario Nacional 2008. Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería de Paraguay. Asuncion, Paraguay

Seyler D (1988) The economy. In: Hanratty DM, Meditz SW (eds) Paraguay: a country study. Library of Congress Country Studies, Washington DC

Stehman SV (2013) Estimating area from an accuracy assessment error matrix. Remote Sens Environ 132:202–211. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2013.01.016

The Nature Conservancy (2005) Evaluacion Ecoregional del Gran Chaco The Nature Conservancy. South American Conservation Region, Buenos Aires, p 28

Vallejos M, Volante JN, Mosciaro MJ, Vale LM, Bustamante ML, Paruelo JM (2015) Transformation dynamics of the natural cover in the Dry Chaco ecoregion: a plot level geo-database from 1976 to 2012. J Arid Environ. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2014.11.009

Vargas Gil R (1988) Chaco sudamericano: regiones naturales. In: X Reunión Grupo Campos y Chaco. FAO UNESCO MAB INTA. La Rioja, Argentina. pp 16–20

Vidal J (2010) Chaco deforestation by Christian sect puts Paraguayan land under threat. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/oct/05/chaco-paraguay-deforestation

Volante JN, Alcaraz-Segura D, Mosciaro MJ, Viglizzo EF, Paruelo JM (2012) Ecosystem functional changes associated with land clearing in NW Argentina. Agric Ecosyst Environ 154:12–22. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2011.08.012

Waske B, van der Linden S, Oldenburg C, Jakimow B, Rabe A, Hostert P (2012) imageRF—a user-oriented implementation for remote sensing image analysis with random forests. Environ Model Softw 35:192–193. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.01.014

Woodcock CE et al (2008) Free access to Landsat imagery. Science 320:1011

World Wildlife Fund (2015) Soy and deforestation—the Gran Chaco. http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/footprint/agriculture/soy/soyreport/soy_and_deforestation/the_gran_chaco/. Accessed 16 March 2015

Zak MR, Cabido M, Hodgson JG (2004) Do subtropical seasonal forests in the Gran Chaco, Argentina, have a future? Biol Conserv 120:589–598. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.03.034

Zak MR, Cabido M, Caceres D, Diaz S (2008) What drives accelerated land cover change in central Argentina? Synergistic consequences of climatic, socioeconomic, and technological factors. Environ Manag 42:181–189. doi:10.1007/s00267-008-9101-y

Zhu Z, Woodcock CE (2012) Object-based cloud and cloud shadow detection in Landsat imagery. Remote Sens Environ 118:83–94. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2011.10.028

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support for this research by the German Research Foundation (DFG, KU 2458/5-1), by the Federal Ministry of Science and Education (BMBF, PASANOA 031B0034A), by the Einstein Foundation Berlin and the Argentine National Agricultural Technology Institute (INTA, PNNAT 1128052). We are grateful for comments made by the two anonymous reviewers, whose comments greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editor: Nicolas Dendoncker.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann, M., Israel, C., Piquer-Rodríguez, M. et al. Deforestation and cattle expansion in the Paraguayan Chaco 1987–2012. Reg Environ Change 17, 1179–1191 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1109-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1109-5