Abstract

Auckland, the largest city of New Zealand, is one of the most diverse cities in the world, with more than 40% of its population born abroad, more than 200 ethnicities represented and 160 languages spoken. In this paper, we measure residential sorting of individuals in Auckland by their cultural (ethnicity) and economic (income, education and occupation) characteristics for the years 1991–2013. Using entropy-based measures of residential sorting and of neighbourhood diversity, we find that individuals exhibit greater residential sorting by ethnicity than by economic characteristics. Geographically, the semi-rural fringes of the city exhibit less diversity than the central urban area. Multi-group indexes of cultural and economic sorting showed a small decline over the 1991–2013 period. We also observe that ethnic sorting declined over that period for broad ethnic groups, but that sorting within the broad ethnic groups increased since 2001. A similar pattern of decreasing sorting at the aggregate level, with increasing sorting within groups in the more recent sub-period, is observed for occupations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A ubiquitous and persistent phenomenon around the world is that the spatial distribution of a city’s population is, in terms of its cultural and socio-economic characteristics, not random but systematic and clustered. Such residential segregation, also referred to more broadly as spatial sorting, can be thought of as the degree to which groups live away from each other (Denton and Massey 1988; Johnston et al. 2007). Spatial sorting has many geographical, historical, institutional, economic and behavioural determinants (e.g. Musterd 2005). Residential sorting can occur in terms of age, language, religion, ethnicity, race and income, or other socio-economic characteristics like industry of work, or occupation.

Schelling (1971) argued that all of the characteristics that may exhibit residential segregation are interrelated. People locate according to their preferences and constraints, and individuals like to stay in close contact with people with whom they share similar characteristics. Networks are often driven by common ethnicity or language use, as such networks facilitate communication and trust. This leads people of the same cultural identity to cluster together. Moreover, house prices and rents are spatially highly correlated, leading to clearly defined low-cost and high-cost housing areas. Consequently, people may be found to live near others with a similar income, as their capacities to afford housing are then similar. Industry and occupation are, besides age and education, also important predictors of income. People with similar jobs tend to have similar incomes, generating another source of similarity of residential preferences and choices (Schelling 1971). Understanding and measuring existing residential sorting patterns is crucial for forecasting future housing demands, local transport and infrastructural and communal facilities, as well as services such as education and health.

Neighbourhood composition influences social and economic outcomes (Maré et al. 2012). The repercussions of residential segregation for individual well-being and opportunities (e.g. Bennett 2011) are a major concern in many countries. If particular socio-economic groups are concentrated in particular neighbourhoods, this may exacerbate existing inequalities in terms of earnings, wealth and poverty (Grodsky and Pager 2001). Racially concentrated poor neighbourhoods may be more susceptible to social problems like lower quality social institutions, increased crime, low property values, lower education levels and lower employment opportunities (Halpern-Felsher et al. 1997; Massey and Denton 1993).

One important, and related, trend in recent decades is the strong growth in international migration which has been making cities more culturally diverse and is expected to continue to do so in the future (Poot and Pawar 2013). The migrant flows’ mixture of temporary and permanent highly skilled ‘talent’ and lower-skilled workers may increase socio-economic diversity of a city, in addition to cultural diversity. Immigration may increase diversity at local levels, but counteracting this is the tendency of migrant groups to cluster as well (White and Glick 1999).

A particularly interesting case is that of Auckland, the largest city of New Zealand, which has become one of the most diverse cities in the world, with more than 40% of its population born abroad, more than 200 ethnicities represented and 160 languages spoken. Much of this diversity is due to immigration since the 1990s, but this has been superimposed on historical diversity resulting from a strong presence of the indigenous Māori population, many of whom were attracted to the city from their iwi (tribal) areas for employment (e.g. Pool 1991). Auckland is now highly diverse in terms of ethnicity, country of birth, socio-economic status, gender and age (Auckland Council 2018).

Consequently, we focus in this paper on the cultural and economic diversity of Auckland. We measure cultural diversity by ethnicity. Ethnicity is an integral expression of an individual’s culture (Betancourt and López 1993). In the New Zealand Census, the ethnicity of an individual is defined as including any ethnic group that the individual identifies with (Statistics New Zealand 2013a). New Zealand residents can affiliate themselves with multiple ethnicities in the Census and some other collections of official data (Kukutai 2008). The extent to which individuals have been identifying with multiple ethnic groups has been increasing. Moreover, resulting from large increases in migration flows since the 1990s—with recruitment based on job skills, financial assets and family ties—and the abolition of a governmental preference for traditional source countries (the United Kingdom and some other European countries), there has been a rise in the number of distinct ethnic identities in New Zealand (New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage 2015). Hence, the ethnic composition of New Zealand is changing, with the Māori, Pacific and Asian ethnic group proportions growing faster than the European proportion (Statistics New Zealand 2004). The population of New Zealand has also a high rate of residential mobility, as well as increasing inter-ethnic marriage and cohabitation (Statistics New Zealand 2007). To maximise the benefits and adapt to changes associated with such an increasingly diverse population, more research is needed to better understand this growing diversity and its impacts (Spoonley 2014).

Table 1 shows the growth and changing ethnic mix of Auckland’s population between 1991 and 2013.Footnote 1 Over this period, Auckland’s population grew from 0.9 million in 1991 to 1.4 million in 2013 and accounts for about one-third of New Zealand’s population. The ratio of the number of ethnicities declared (total responses) to the population increased between 1991 and 2013 from 1.05 to 1.11, which is indicative of growth in people identifying with more than one ethnicity over this period. It should be noted, however, that the number of individuals without a stated or imputed ethnicity increased from 1 to 6% of the population. European ethnicity decreased from 72% of total responses in 1991 to 54% in 2013. If we define ‘superdiversity’ as the case in which no single major ethnic group represents a majority in the population, it is clear that Auckland is close to becoming superdiverse (see also Cameron and Poot 2019).

Those who report that they identify with Māori ethnicity represent a fairly stable 10% of total responses. During the 19th century colonialization period, this indigenous population lost much of their lands and resources. They also tended to live in poorer and more crowded houses than Pākehā.Footnote 2 As noted above, many Māori migrated after the Second World War to the cities for work. Postwar industrialisation and import substitution policies led to very low unemployment and a high demand for labour. Since the 1950s, Pacific people were also encouraged to migrate to New Zealand’s cities, particularly Auckland, to meet the growing demand for labour. When economic conditions deteriorated in the 1970s, restrictions on Pacific migration were increased. A points system for immigration introduced in the 1990s also favoured skills over family ties. Some Pacific migration nonetheless continued. Over the 1991–2013 period, the proportion of responses identifying with a Pacific ethnicity increased from 11 to 13%.

From the late 1980s and the removal of the ‘traditional source country’ criterion, migrants from non-traditional source countries began migrating to New Zealand in larger numbers, especially from Asia. In 1991, only 5% of Auckland’s ethnicity responses identified with an Asian ethnicity, but the proportion increased sharply to about 21% in 2013. Though the Asian population has increased in every region in New Zealand, the largest increase has been observed in Auckland (Statistics New Zealand 2019b). The largest two Asian population sub-groups in 2013 were Chinese and Indian (Statistics New Zealand 2019b). Besides employment-related migration, another cause of the growth in the Asian population is a large influx of international students undertaking tertiary studies, some of whom are settling in Auckland afterwards.

Responses of ethnicities from the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa (MELAA) and ‘Other’ make up a very small but growing percentage of total responses, up to 2.7% in 2013. The large percentage of ‘Other’ in 2006 is an anomaly due the introduction on the census form of a separate ethnicity of ‘New Zealander’, which was highly publicised and politicised in the media at the time and was mostly selected by New Zealand Europeans. The category was kept in the 2013 census, but the number selecting it at that time had dropped by 85% compared with 2006.

The growing ethnic diversity of Auckland’s population is clearly impacting on the patterns of segregation and spatial sorting that we will analyse in this paper. In the remainder of the paper, we prefer to use the terms ‘residential sorting’ or ‘spatial sorting’ where possible, to encompass a range of spatial population distribution phenomena that include segregation, isolation, and concentration. Our preferred terms are not only broader than the conventional term of spatial segregation, but also carry none of the negative connotations associated with the latter.

Spatial sorting can create a vicious cycle of disadvantages—a lack of secure and well-paid employment in one’s neighbourhood, or at commuting distance, leads to low income, which in turn leads to low-quality housing. Low-quality housing makes it hard to maintain good health. Low income can create barriers to access to good education, which leads to low future employment opportunities for children, which reinforces income inequality across generations (Dalziel 2013). This makes it important to understand how sorting patterns by economic variables are related to sorting patterns by cultural variables (such as ethnicity).

Income inequality in New Zealand rose rapidly during the 1980s and early 1990s, and this increase was more rapid than in other developed countries (Alimi et al. 2018). Additionally, income inequality increased particularly fast in Auckland (Alimi et al. 2016). While inequality has been fluctuating since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Global Financial Crisis triggered a further increase. Socio-economic inequality intersects with ethnicity. In 2013, the average income of Māori was 78.9% of that of non-Māori. One-third of Māori aged over 15 had no school qualifications, and only 6% of Māori and 2% of Pacific people held a bachelor’s degree. Though there have been improvements in socio-economic indicators (life expectancy, education, employment and income) over time, there has been a relative decline in the number of Māori employed in skilled occupations. Pacific people are also a relatively large proportion of the unemployed, lower-skilled and low-income workers in Auckland and have substantially lower incomes than other ethnic groups (Auckland Council 2018). Māori and Pacific peoples live disproportionately in low-income households due to a complex set of circumstances, economic transformations and a succession of past policies, since colonial times for the former, and since the 1970s for the latter.

Given this background to the demographic and socio-economic changes in Auckland in recent decades, in this paper we focus on identifying the changes in residential sorting over time. Specifically, the purpose of our paper is to address the following research questions:

-

(i)

Has residential sorting been declining over time in Auckland?

-

(ii)

Is residential sorting by cultural factors greater than residential sorting by economic factors in Auckland?

-

(iii)

Is residential sorting mostly driven by sorting between broad groups, or within broad groups (i.e. by sorting between sub-groups)?

While this is not the first paper to consider these, or related, research questions, there are several novel aspects to our analysis. First, we use entropy as the mathematical principle for measuring both spatial sorting and diversity. While entropy is not an uncommon approach to diversity and sorting in the literature, our paper is to our knowledge the first contribution using entropy in the New Zealand context. One of the main advantages of entropy measures is their property that an aggregate index can be decomposed into the weighted sum of within-group and between-group measures (Theil 1972). We use this property to see how sensitive the residential sorting index values are to the level of aggregation in our data, and to answer our third research question.

The second contribution of this paper is that we consider spatial sorting in Auckland over a fairly long period of nearly a quarter century (1991–2013), while earlier work has tended to capture shorter periods. Third, while earlier work has addressed the impact of varying granularity of the spatial data (i.e. the definition and size of areas), we are able to quantify the effect of changing the granularity of the classification. We do this for a cultural variable (ethnicity) and an economic variable (occupation).

Regarding the first research question, Manley et al. (2015) found that, at a micro-scale, ethnic residential sorting in Auckland declined from 2001 to 2013. Related to the third research question, Manley et al. (2019) found that the intensity of segregation for larger ethnic groups in Auckland remained static over the 2001 to 2013 period, but reduced drastically for smaller ethnic groups. Here, we revisit these trends over the longer period 1991–2013. A longer time frame is important given the radical economic reforms that took place in New Zealand during the decade following 1984 (Evans et al. 1996).

Regarding the second research question, Maré et al. (2012) found stronger residential sorting by ethnicity than by income or qualification in Auckland, but using data for 2006 only. This New Zealand finding is consistent with US evidence of greater segregation by ethnicity than by social class measured by education or occupation or income (Farley 1977; Sims 1999). Here, we revisit whether residential sorting in Auckland is greater by ethnicity than economic factors (income, qualification and occupation) when we use our dataset for the 1991–2013 period.

Regarding the third question, past New Zealand studies (Johnston et al. 2008; Maré et al. 2011) have already found that similar groups (i.e. sub-groups belonging to a larger ethnic group) tend to co-locate. That suggests a high degree of sorting of ethnic sub-groups within high-level ethnic groups. Decomposing multi-ethnic segregation in Auckland at multiple spatial scales was recently undertaken by Manley et al. (2019), following Lichter et al. (2015) who used the Theil index to decompose metropolitan segregation in the USA into its within- and between-place components from 1990 to 2010. Fowler et al. (2016) undertook a similar kind of study to evaluate the roles of area types in ethno-racial change. Our study complements these earlier works, by considering within-and-between ethnic group and occupational group components of sorting rather than spatial components.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2, we discuss relevant studies on residential sorting, with a particular focus on North American, Australian and New Zealand research. Section 3 describes the data, and Sect. 4 details the methods. Section 5 presents and discusses the results, and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Background literature

Of all countries in which there has been research on residential sorting by ethnicity/race, education, income and/or occupation, the largest number of studies has been conducted for the US Recent reviews that refer to key contributions to this vast literature can be found in Lee et al. (2019) and Hall et al. (2019). In one of the earliest such studies, Duncan and Duncan (1955) found that the most segregated occupational groups were the ones with the highest and the lowest rankings in terms of socio-economic status. Farley (1977) measured the degree of socio-economic and residential segregation in central cities and densely populated suburban areas and found that minority individuals in the USA tended to cluster with other minority group members. Simkus (1978) found that gross occupational residential segregation in urbanised areas increased slightly during the 1950s but, taking race into consideration, levels of racial residential segregation between White residents and non-White residents in the lowest occupation groups in 1960 were low. Massey (1979) used 1970 Census data and found that segregation of the Spanish-American and White populations declined with increases in socio-economic status. Denton and Massey (1988) used data from the 1980 US Census to look into patterns of residential segregation by socio-economic status. They showed that the Black population were strongly segregated from the ‘Anglo’ population irrespective of their occupation, educational qualification, or income. Ellis et al. (2004) found ethnic minority groups to be more segregated in the labour market than in the housing markets, and that more intergroup contact takes place during work hours than in the home environment, which results in less workplace segregation. Johnston et al. (2004) demonstrated that the interurban variations in segregation levels between US Metropolitan Statistical Areas are strongly related to urban size, ethnic diversity and relative size of the individual minority groups.

Overall, studies in the US (e.g. Domina 2006; Duncan and Duncan 1955; Farley 1977; Fischer 2003) demonstrate substantial residential segregation based on ethnicity and socio-economic variables. Education, occupation and income make up an individual’s social status together with ethnicity (Weeden and Grunsky 2005), and these dimensions are related and jointly reinforcing. Florida and Mellander (2018) therefore compared cultural with occupational, income and educational segregation as well as a combined measure of overall economic segregation. They emphasise that income is a consequence of education and occupation and, thus, to understand economic sorting, the latter factors should be considered as well. They applied measures of sorting to the different economic variables and formed an Overall Economic Sorting Index by averaging the sorting index values for the individual economic variables. They found that economic segregation is associated with more highly educated, larger and denser metro regions. They also found that economic segregation is related to ethnicity, mode of transport and income inequality.

There is also a substantial literature on residential sorting outside of the USA for New Zealand research, Canadian studies are also particularly relevant. Balakrishnan et al. (2005) conducted a comparative study on residential segregation across major CMAs (Census Metropolitan Areas) in Canada using 2001 census data. They found considerable variation in segregation levels across these CMAs. They did not find any systematic relationship between residential segregation and socio-economic achievements (education, occupation and income). Walks and Bourne (2006) used 1991 and 2001 Canadian census data and found that Toronto, Vancouver, Montréal and Winnipeg were the most residentially segregated CMAs in Canada. They also found that the Black population and the Latin American population show patterns of high residential segregation, as they are less economically successful than the other ethnic groups. Fong and Hou (2009) looked into residential patterns of three minority groups (South Asian, Chinese and Black populations) in the four largest metropolitan areas of Canada (Calgary, Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver) using 2001 census data. They found that these minority groups show patterns of residential integration over generations.

In Australia, studies of residential sorting are based on ancestry data, as the Australian census does not ask any direct question related to an individual’s ethnic identification. Instead, respondents can state up to two ancestries and, for the foreign born, country of birth is also known. Forrest et al. (2006) found spatial desegregation of non-host ancestral groups and Aboriginal people in metropolitan regions of Australia, using data from the 2001 Census. Their results suggest that the presence of ethnic clusters is a temporary phenomenon in Australia. Johnston et al. (2007) used 2001 Australian census data to describe levels of segregation in Australia and to analyse the factors affecting the levels of segregation. They found that residential segregation was most prominent in larger cities and where the minority ethnic groups formed a large proportion of the total population. Johnston et al. (2016) used 2011 Australian census data and analysed residential segregation of 42 ancestral groups in Sydney. They found that segregation is more prominent among smaller ancestral groups, the most recently arrived, and individuals who are culturally different from the host society. For all ancestral groups, segregation was greater at the macro- (regional) and micro (neighbourhood)-level than at the intermediate meso (suburban district)-levels.

For New Zealand, most studies have focused on ethnic residential sorting using data from the population census. In contrast with our paper, which covers the 1991–2013 period, there have been few previous studies concerned with longer-term trends in residential sorting. Moreover, previous studies of residential segregation in New Zealand have mainly looked at a limited number of ethnic groups, or groups by country of origin or birth (e.g. Maré et al. 2016). Johnston et al. (2002) showed the presence of prominent residential concentration patterns among Polynesians (that is, Pacific Peoples plus Māori). Johnston et al. (2005) analysed variations in the degree of residential segregation of the Māori population across the urban areas of New Zealand from 1991 to 2001. They found that the degree of segregation for this ethnic group varies according to the relative group size within each urban area. Johnston et al. (2008) showed that, in 2006, the Pacific Islander group was the most residentially segregated in Auckland. Johnston et al. (2011) used New Zealand Census data from 1991 to 2006 and found that, in comparison with Māori, Pacific Peoples were more likely to cluster in areas where their co-ethnics dominated.

Few studies in New Zealand have looked at residential sorting by characteristics other than ethnicity. Like Johnston et al. (2008), Maré et al. (2011) found that the greatest residential sorting in Auckland is by Pacific Peoples, but also by people with university degrees. In another paper, Maré and Coleman (2011) found that ‘own-group’ attraction was a much stronger determinant of residential sorting than urban amenities. Maré et al. (2012) found that the Pacific Islanders, people with higher university degrees and with higher levels of education, higher income and the elderly, exhibited the greatest levels of residential sorting. Finally, Maré et al. (2016) studied the residential assimilation of immigrants after their arrival in Auckland, using census data from 1996 to 2006. The groups included in the study were limited to immigrants from the United Kingdom, China, India, South Africa and the Republic of Korea. They found distinct patterns of residential assimilation for most of the immigrant groups. They also found that the longer that immigrants from each group had spent in the host country, the more their residential concentration declined. Manley et al. (2015) looked at changing ethnic residential sorting among the main four broad ethnic groups (European, Māori, Asian and Pacific Peoples) in Auckland for the period from 2001 to 2013. They found that at each of three geographical scales [macro (localities); meso (area unit); micro (meshblock)], Pacific Peoples were the most and Europeans were the least residentially segregated. They also found that a decline in residential sorting at the micro (meshblock)-level could be observed for Māori, Asian and Pacific Peoples.

As noted in the introduction, our paper contributes to the growing literature on residential sorting in New Zealand. We use a finer-grained categorisation of ethnic groups than used in previous research in New Zealand to better capture the heterogeneity within the broad ethnic groups. Unlike previous research in New Zealand, we also look into long-term trends (close to a quarter century) of residential sorting and we use entropy as a mathematical principle for measuring sorting and diversity. Additionally, we measure overall economic sorting in Auckland by means of a combination of income, occupation and qualification (following Florida and Mellander 2018). Finally, we also consider how much between-group and within-group sorting contributes to the overall level of sorting, which has not been previously done in New Zealand (or elsewhere, to our knowledge).

3 Data

We obtained population data from the 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2013 New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings for the Auckland metropolitan region of New Zealand. The New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings is usually conducted every 5 years (the 2011 census was delayed until 2013 due to a large earthquake in Christchurch) and collects a range of socio-demographic information on each member of the New Zealand population present and normally resident in New Zealand on census night. The census data on each individual include characteristics such as location of usual residence, age, sex, ethnicity, income level, occupation, education and marital status. These microdata can be aggregated to population statistics at various spatial levels. For the purpose of the present paper, each measure of residential sorting (described below) was calculated based on data aggregated to the area unit level for individuals aged 22 years and above.Footnote 3 The Auckland region is made up of 413 area units. Their median area is 169 hectares (1.3 km by 1.3 km). Four area units had no usually resident population in any of the censuses and were therefore dropped, leaving 409 for the analysis.

In accordance with the strict confidentiality rules laid down by Statistic New Zealand, the summary statistics, counts and calculations are based on data that have been suppressed for raw counts less than six and otherwise randomly rounded to base three.Footnote 4

An ethnic group consists of people who generally have any of the following: common proper name of the group, common elements of culture, similar interests, feelings and actions, or share a common ancestral as well as geographic origin (Statistics New Zealand 2013a). A person’s ethnicity is the ethnic group or groups that that person identifies with or feels a sense of belonging to. It is a measure of cultural affiliation (in contrast to race, ancestry, country of birth, or citizenship). Ethnicity is self-perceived, and a person can belong to more than one ethnic group. New Zealand residents can change their ethnic affiliation for statistical purposes at any time.

According to the New Zealand Standard Classification of Ethnicity, ethnicity is classified in a hierarchy of four levels. An individual reporting more than one ethnicity is included in each ethnic group that they report (this is referred to as ‘total count’ ethnicity) (Statistics New Zealand 2015). The main (Level 1) ethnic groups defined in the Census are: European, Māori, Pacific Peoples, Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American & African (MELAA) and Others. Given the considerable heterogeneity expected within each of these broad ethnic groups, we also use data on Level 2 ethnic groups.Footnote 5 In our analysis, we proportionally distributed the population counts of the ‘not further defined’ category for three Level 2 ethnic groups into the corresponding Level 2 groups within the same Level 1 ethnic group.Footnote 6

Two issues affect the comparability of ethnicity data in New Zealand over time. First, the format and wording of the Census ethnicity question changed twice between 1991 and 2001. In 1991 and 2001, the question was almost the same, but both differed substantively from the question in 1996.Footnote 7 Thus, comparability across Censuses is likely to be affected. Substantial changes include increased multiple responses in 1996 and a consequent reduction in single responses, and a tendency for respondents to answer the 1996 question on the basis of ancestry (or descent) rather than ethnicity (or cultural affiliation). These inconsistencies apply particularly to the ‘European’ ethnic groups (including ‘New Zealand European’) and the ‘Māori’ ethnic group. In the 1996 data, the count for ‘Other Europeans’ was much higher than in the 1991 or 2001 data. The count for the ‘New Zealand European’ category decreased in 1996, which can be attributed to the fact that in 1996, people saw the additional ‘other European’ category as being more suitable to describe their ethnicity than the ‘New Zealand European’ category (Statistics New Zealand 2017a, b, c). For example, van der Pas and Poot (2011) noted that in the 1996 Census, almost 48,000 people identified themselves as Dutch, compared with just 27,866 in 2001 and 29,000 in 2006.

Second, the treatment of responses of ‘New Zealander’ to the Census ethnicity question has changed over time. In 2001, those who considered themselves simply to be a ‘New Zealander’ were likely to have been counted in the New Zealand European category. However, in 2006 New Zealander was explicitly included as a new category and this change received much publicity in the media. This was no longer a prominent issue by 2013, and the increase in counts for the New Zealand European category from 2006 to 2013 is therefore partly attributable to fewer people identifying themselves as ‘New Zealander’ by 2013.

We use three different variables in our analysis of economic residential sorting (viz. educational attainment, occupation and income). For educational attainment, we use the variable ‘Highest Qualification’ for all years from 1996 onwards.Footnote 8 The classifications under this category for 1996 and 2001 are different from those for 2006 and 2013.Footnote 9 Due to unavailability of data on the same variable for 1991, we used ‘Highest Secondary School Qualification’ for 1991.Footnote 10 This issue affects our results over time somewhat, but is not expected to have impacted on our conclusions.

In the Census, an ‘occupation’ is defined as a set of jobs that require an individual (including the self-employed) to perform identical sets of tasks (Statistics New Zealand 2013a). We use the New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (NZSCO99),Footnote 11 which is a five-level hierarchical classification with nine broad major groups (Statistics New Zealand 2015). As in the case of ethnicity, we use both Level 1 and Level 2 occupation levels. From 1991 to 2013, reporting and classification of occupations in the New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings has changed (Hancock 2015). Since 1996, the group ‘Armed forces’ has been included under ‘Personal and Protective Service Workers’. Therefore, we combined these groups for the calculations in 1991 as well.

Finally, we also use data on total personal income.Footnote 12 The number of income intervals and the bounds have changed over the years due to inflation and real income growth.Footnote 13 For simplicity, we have not attempted to adjust the data to a common set of intervals. This might affect the year-wise comparability of the sorting values; however, it is unlikely to substantially impact the conclusions drawn from the analysis.

For all variables, we aimed to keep the number of groups similar, for better comparability in sorting, as residential sorting measures are sensitive to the number of groups (Mondal et al. forthcoming). For example, 18 groups were used in the analysis of ethnic sorting in 2018 and 16 income groups. In any case, where we measure diversity in an area unit we use the Evenness Index, which corrects for the number of categories in the classification. This is elaborated in the next section.

4 Methodology

There are many different measures that can be used as indicators of residential sorting (see, e.g. Massey and Denton 1988; Nijkamp and Poot 2015; Reardon and Firebaugh 2002). We choose entropy-based measures of residential sorting and diversity, following the seminal contribution by Theil and Finezza (1971). Entropy measures are conceptually and mathematically attractive and provide the only multi-group index than can be decomposed into a sum of between- and within-group components (Reardon and Firebaugh 2002). Additionally, we provide the first application of this approach with New Zealand data.

From information theory, we define the (Shannon) entropy of a system X,\( \left( { H\left( X \right)} \right) \), with possible outcomes x1, x2, … xN and p(xi) the probability of state xi occurring, as:

Interpreting the fraction of a population that belongs to a certain group as the probability of a randomly selected person belonging to that group, we can define the diversity (entropy) index \( (E_{a} ) \) of the population in area a in terms of a given classification as:

in which \( P_{ga} \) is the number of people from group g (= 1, 2, …, G) located in area unit a (= 1, 2, …, A), and \( P_{a} \) is the total number of people in area unit a. We will additionally denote \( P_{g} \) as the number of members of group g in Auckland and \( P \) to be the total number of people in Auckland. The minimum of the diversity index is reached when only one of the groups is present, in which case \( E_{a} = 0 \).Footnote 14 Maximum diversity occurs when all groups are equally represented in area unit a, in which case \( E_{a} = { \ln }\left( G \right) \). Because we are considering classifications that have different numbers of categories, it is convenient to normalise the entropy diversity index to an evenness index Ia that varies between zero and one in all cases (e.g. Nijkamp and Poot 2015):

To investigate the geographical differences in diversity across Auckland area units, we calculated the evenness index of each area unit in Auckland for each of the four classifications and use choropleth maps to show the spatial distribution of this diversity measure across Auckland. Following Florida and Mellander (2018), we also averaged the area unit diversities (with equal weights) for the three economic (income, qualification and occupation) variables in each census to create an overall economic diversity measure which can be compared with the cultural diversity measure based on ethnicity.

Spatial sorting can be defined as the average extent to which diversity of an area unit differs from that of the city as a whole. Hence, if we compare group g with all other groups combined, the entropy of area a \( (E_{ga} ) \) becomes:

while for the city as a whole \( (\bar{E}_{g} ) \) it is:

A natural measure of spatial sorting/segregation of group \( g(EIS_{g} ) \) is then (see, e.g. Iceland et al. 2002):

which is simply the area-population weighted average of one minus the relative entropy of the areas \( \left( {\frac{{E_{ga} }}{{\bar{E}_{g} }}} \right) \) with respect to group g. This index varies between zero (when the group is distributed proportionally to the total population in all area units) to one (when all areas in which group g is represented contain no other group).

When the composition of a city’s population in terms of groups according to a classification (ethnicity, occupation, etc.) changes, it is useful to have an overall measure of residential sorting for the city that accounts for whether segregated groups are becoming more or less important. This overall measure is Theil’s Multi-group Segregation Index H (Theil 1972; Theil and Finezza 1971; White 1986). To calculate this index, we first measure the city-wide entropy (diversity) (E) of the classification, i.e. \( E = - \mathop \sum \limits_{g = 1}^{G} \frac{{P_{g} }}{P}\ln \frac{{P_{g} }}{P} \). We also calculate the ratio \( r_{ga} = \frac{{P_{ga} }}{{P_{a} }}/\frac{{P_{g} }}{P} \) which measures the extent to which a group is overrepresented (\( r_{ga} > 1 \)) or underrepresented (\( r_{ga} < 1 \)) in area a. Theil’s multi-group spatial sorting index (\( H) \) is now calculated as follows (e.g. Reardon and Firebaugh 2002, Table 1):

Essentially, H measures the group-population weighted average of the extent to which the spatial distribution of a group differs from the spatial distribution of the entire population. H varies between zero and one. The index is zero when all areas have the same population composition. The index is one if there is, for each group in the classification, no area in which more than that one group is represented. An alternative way of calculating an overall city index of residential sorting (\( H^{*} ) \) is to simply take the group-population weighted average of EISg, i.e. to calculate:

This calculation gives approximately the same value as H, but is easier to interpret. We calculate this measure to investigate whether residential sorting has been changing over time in Auckland. We also use the H* values calculated for each classification to compare residential sorting by cultural and economic factors in Auckland. Yet another way of calculating H is to exploit the property that it measures the relative extent to which the diversity of city as a whole differs from the population-weighted average of the area units’ diversity (Theil and Finezza 1971; White 1986). The diversity of the city is given by E as defined previously. We can then calculate H also as follows:

Finally, following Reardon et al. (2000), we consider the impact of multi-level classification on Theil’s Multi-group Segregation Index H. Considering different levels of aggregation, we decompose the index values into between-group and within-group components and show how sensitive the sorting index is to the level of aggregation in the classifications. In our case, we consider a classification with two levels (coarse—single digit—and more refined—double digit) for both ethnicity and occupation, as only these two measures have multiple levels of classification that allow for this decomposition.

Specifically, consider that g = 1, 2, … G indexes the most detailed classification and that n = 1, 2, … N is an aggregation of these groups into a smaller number of broader groups (i.e. N ≪ G). Theil’s Multi-group Sorting Index values (H) can be decomposed into between-group and within-group components for ethnicity and occupation using the following formula:

(see Reardon et al. 2000; Reardon and Firebaugh 2002). Here, \( H \) is the Theil index calculated over all groups in the city (Level 2), \( H_{N} \) is the Theil index calculated among the Level 1 groups, and \( H_{n} \) is the Theil index calculated within each of the Level 1 groups (i.e. between the Level 2 groups). \( E_{N} \) is entropy among the supergroups (Level 1), \( E_{n} \) is the entropy within Level 1 group n, and E is the entropy of the population as a whole (i.e. Level 2). P and \( P_{n} \) are, respectively, the size of population as a whole and the population size of Level 1 group n.

5 Results

Figure 1 shows choropleth maps of the evenness scores of area units in Auckland for each of the variables in 2013. Lower values represent lower levels of diversity and are signalled by lighter colours on the map. For reference, Panel (a) in Fig. 1 shows a map of the 13 wards (which elect the Auckland Council mayor and 20 Councillors) as well as the 21 local boards (that are concerned with local issues) that make up the Auckland area (Fathimath 2017). The Central Business District is in the Waitamata and Gulf ward. Panel (b) shows that ethnic diversity varies widely across the city. Generally, the central urban area exhibits much greater diversity than the rural fringes. Ethnic diversity is also much greater south of the city centre than north of the city centre and harbour bridge. Central Auckland has two large tertiary institutions along with many language schools and other training institutions, which attract students from overseas and contribute to high ethnic diversity in central Auckland. Moreover, the two largest contributors to the Skilled Migrant visa category are India and China (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment 2016), and their residential location is also relatively clustered (Maré et al. 2016).

Source: Fathimath (2017). b Evenness index—Ethnicity. c Evenness index—Qualification. d Evenness index—Occupation. e Evenness index—Income

Diversity in Auckland by Cultural and Economic Variables, 2013 a Auckland Wards and Local Boards

The evenness scores for the economic variables are displayed in Panels (c)-(e) in Fig. 1. These use the same legend as Panel (b). In terms of diversity across qualification groups, there is less diversity in south Auckland and in those parts of the city centre where students dominate. Qualifications and ethnicity evenness values are actually negatively correlated (r = − 0.35). In contrast, evenness scores of ethnicity are positively correlated (r = 0.37) with those of occupation shown in Fig. 1d. On the whole, the map for occupations shows less spatial contrast than for education and a lower average evenness score across area units. The lower occupational evenness score in the CBD reflects the dominance of the services sector there. The map for income (Fig. 1e) shows a spatially dominant high level of evenness. This simply reflects a fairly even distribution everywhere of the population across the income categories,Footnote 15 but it is not necessarily indicative of low income inequality. We do observe lower evenness where students live and in the south of Auckland. Income and ethnicity evenness values are negatively correlated (r = − 0.20). In general, it is clear that there are more spatial differences in Auckland in terms of cultural diversity than in terms of any of the economic variables.

Figure 2 shows the relationship between 1991 and 2013 values of the evenness measure of diversity in each area unit of Auckland for each of the variables, where each dot represents one area unit. In the figures, almost all observations for all the variables, except for occupation, lie above the 45-degree line. This means that for most area units in Auckland, diversity has increased between 1991 and 2013, except for occupation (Panel (c)). For occupation, area units appear roughly equally split between those that had increasing diversity and those that had decreasing diversity.

Table 2 reports the Auckland-wide evenness indexes over the period 1991 to 2013. This shows that Auckland has generally become more economically and culturally diverse. For all of the variables except occupation, diversity has increased over this period.Footnote 16 In the case of occupation, the downward trend in evenness can be attributed to the growing dominance of services and related occupations in New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand 2017a, b, c).

5.1 Sorting by ethnicity

Table 3 shows the Entropy Index of Sorting values for ethnicity in Auckland in 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2013. We observe that for all Level 2 ethnic groups within the Pacific Island broad ethnic group, along with the Chinese and Indian ethnic groups, there has been an increase in spatial sorting. These groups appear to show Schelling-type behaviour in that they appear to be increasingly seeking to live with their co-ethnics (Schelling 1971). In Auckland, groups of Chinese are clustered in the wealthier suburbs, but most are concentrated in middle-priced suburbs. The Indian population is also observed to have major concentrations in these areas. A large number of Asian students are concentrated in central Auckland, which is near the largest tertiary institutions (Ho 2015). Friesen (2008) also found a significant level of clustering among the Asian population in Auckland. A ‘zone of familiarity’, including provision of ethnic goods and services and employment in ethnic businesses run by co-ethnics may contribute to this outcome. Poulsen et al. (2004) found that despite policies promoting multiculturalism in New Zealand, many among the Chinese or Indian ethnic groups choose to maximise their economic success by being involved in small businesses serving their own community and thus reside in neighbourhoods with a larger proportion of their ethnicity. In contrast to the Chinese, Indian and Pacific groups, Table 3 shows that for the New Zealand European, South-East Asian, and all of the Level 2 ethnic groups within the MELAA broad ethnic group, residential sorting has declined over time.

5.2 Sorting by other variables

In line with the geographically based results reported in Fig. 1, residential sorting by qualification, occupation and income is much less apparent than for ethnicity.Footnote 17 We find that the greatest residential sorting is exhibited by people with high education and high income.Footnote 18 These results are consistent with previous research (Maré et al. 2011, 2012). Maré et al. (2011) found prominent patterns of concentration of residents with high income in specific regions of Auckland, but less distinct patterns for the low and middle income groups.

It can be easily shown by regression that there is a small negative effect of group size on the level of sorting. With respect to occupation, this can be easily illustrated by the ‘Legislators and Administrators’ group, which had the highest level of sorting in 1991 (EIS = 0.361), but only accounted for 0.013% of the Auckland labour force. The next three groups with the highest levels of residential sorting in 1991 (with their 1991 labour force share in parentheses) are: ‘Salespersons, Demonstrators & Models’ (5.65%), ‘Drivers and Mobile Machinery Operators’ (2.9%) and ‘Other Craft & Related Trades Workers’ (1.62%). All of these experienced a notable decline in residential sorting between 1991 and 2013. At the other end of the scale, the four occupational groups with the lowest residential sorting in 1991 were: ‘Office Clerks’ (12.7%), ‘Other Professionals’ (3.54%), ‘Personal & Protective Services Workers’ (7.1%) and ‘Other Associate Professionals’ (7.86%). The groups with the next lowest EIS, ‘Market Orientated Agricultural & Fishery Workers’ (three per cent) experienced a huge 1991–2013 increase in sorting (from 0.016 to 0.171), indicative of the expansion of residential land at the cost of land used for market gardening.

In terms of overall residential sorting, Theil’s Multi-group Segregation Index (H) (see Table 4) shows a decline in ethnic residential sorting between 1991 and 2013 (the low values in 1996 and 2006 are partially due to the census question issues discussed earlier). Table 4 also shows that the residential sorting by income has remained constant over time at this very broad level. However, this does not imply that there are no change in the distribution of ‘poor’ and ‘rich’ areas. The index does not inform on levels of income, but simply on the spread across the census questionnaire income intervals. We observeFootnote 19 a notable increase in residential sorting of those in the ‘open-ended’ highest income category, with EIS increasing from 0.119 in 1991 to 0.135 in 2013, suggesting that the rich are less evenly spread spatially than they used to be.

Residential sorting by occupation shows a downward trend from 1991 to 2006, with a slight increase subsequently.Footnote 20 This might be due to a number of factors. The female labour force participation rate has increased in New Zealand (from 54.3% in 1991 to 64.5% in 2006) (Statistics New Zealand 2017a, b, c). While there is gender segregation in employment by occupation, occupational segregation has declined and there has been a structural transformation in employment towards employment in services. Consequently, whereas there were historically ‘blue collar’ (male employment dominated) and ‘white collar’ area units, that distinction has become less over time (e.g. van Mourik et al. 1989)—leading to lower spatial sorting by occupation. For qualification, the residential sorting trend is also downward (the 1991 value is not directly comparable due to a changing classification).Footnote 21

Comparing the Theil Multi-Group Index across the four chosen characteristics—ethnicity, qualification, occupation and income—we see that the greatest degree of residential sorting occurs by ethnicity. Among the economic variables, residential sorting is greatest by occupation. Again, the lack of residential sorting by income might seem surprising. However, previous research for New Zealand (Maré et al. 2011, 2012) has also found low residential sorting by income. New Zealand has certainly had historically low levels of spatial income inequality. Moreover, the use of personal income instead of household income could also have contributed to low measured sorting by income. Maré et al. (2012) calculated income sorting by personal income as well as household income and found that the sorting values were slightly higher for household income.

Taking the average of the Theil Multi-Group Indexes for the economic variables, following Florida and Mellander (2018), we see from the final column of Table 4 that, firstly, spatial sorting in Auckland is less in economic terms than in cultural terms and, secondly, that ethnic and economic spatial sorting levels are less in 2013 than in 1991.

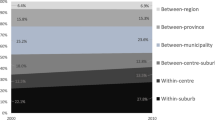

Finally, we show how sensitive the Theil’s multi-group measure of sorting is to the level of aggregation, by decomposing the H values into between-group and within-group components.Footnote 22 We do this for our cultural variable (ethnicity) and one economic variable (occupation). The results for ethnicity are reported in Table 5a, and the corresponding analysis for occupation is reported in Table 5b. The ‘Theil at level 2’ column of Table 5a repeats the index values already reported in the ‘Ethnicity’ column of Table 4. The second and third columns decompose the first column into a share of sorting that occurs between Level 1 ethnic groups, and a share that occurs within Level 1 groups (i.e. between Level 2 groups within the same Level 1 group), as shown in Eq. (9). The fourth and fifth columns show the percentage shares of between- and within-group sorting. In terms of shares, the results imply that the co-location of Level 1 ethnic groups (e.g. Pacific Islanders) has been decreasing over time, but that sorting between Level 2 ethnic sub-groups (e.g. Samoan, Cook Island Māori, Tongan, etc.) within their Level 1 groups has increased in importance. In other words, Level 2 ethnic groups are increasingly sorting away from other Level 2 groups within the same Level 1 broad ethnic group. For instance, there are fewer suburbs that are generic Pacific Island communities, with Samoan, Tongan and other Pacific groups increasingly located separately from each other.

Table 5b repeats the analysis for occupation. In this case, the sorting is higher within Level 1 groups (i.e. between Level 2 groups within each Level 2 group) in all years, and segregation has generally been declining between Level 1 groups and between Level 2 groups within a Level 1 group. The notable exception is the increase in the ‘within Level 1’ component between 2006 and 2013, leading also to an increase in the Level 2 share over that period. This suggests that while there was a trend of enclaves of people of similar occupations within a higher level occupational grouping co-locating less, this trend reversed after 2006. Analysis with 2018 data may reveal whether this reversal is one-off or indicative of longer-term underlying phenomena that lead again to co-location.

6 Conclusion

We applied entropy-based measures of residential sorting and diversity to census data for Auckland over the period from 1991 to 2013. We find that, broadly speaking, residential sorting by ethnicity, qualification and occupation declined over this period, whereas sorting by income remained fairly constant. Calculations with the Theil Multi-group Index reinforced that both cultural and economic residential sorting in Auckland declined over this period.

One of the research questions in this paper was to identify whether individuals exhibit the greatest level of residential sorting by their cultural or by economic characteristics. We considered ethnicity as our cultural variable. We formed our economic index of residential sorting as a combination of income, qualification and occupation, which—as stated by Florida and Mellander (2018)—captures the mutually reinforcing aspects of income, qualification and occupational sorting in a better way than they do individually. We find that residential sorting is greater by cultural factors (ethnicity) than by economic factors (income, qualification and occupation), separately as well as combined.

This result might seem surprising, given that we can imagine enclaves of privilege or relative deprivation. Why then, do the data not support this? Part of the reason is likely to be our chosen level of geographical aggregation. In urban areas, an area unit is approximately the size of a suburb, with an average population of about 2000. If we were to complete our analysis at a lower level of geographical aggregation (e.g. meshblocks, which are roughly neighbourhoods or city blocks), we might observe more residential sorting by these other characteristics. However, small cell sizes would become problematic when conducting this analysis across many groups and many small geographical areas, leading to a greater degree of necessary suppression of data counts (Statistics New Zealand requires this due to concerns about confidentiality of data). This explains why previous analyses that have used meshblock-level data (e.g. Maré et al. 2011) have used more aggregated ethnic or other groups. Our analyses should be seen as complementary to that earlier work. Moreover, the lack of prominent pattern of income sorting might also be due to the use of total personal income and not household income, which might play a role in household location decisions (Maré et al. 2011).

From the decomposition results, we find that individuals are increasingly tending to co-locate more according to their finer ethnic groups than their broad ethnic groups. The finer ethnic groups are not co-locating together with other groups within the same broad ethnic group, i.e. there is spatial heterogeneity of the finer ethnic groups. For example, the Tokelauans and the Niueans co-locate more with their own-group members now, but they do not tend to co-locate with other groups under the broad Pacific group. This can create both problems as well as opportunities for public services (Caldwell et al. 2017). Thus, it is becoming increasingly important to look at residential sorting at a much finer scale.

Our findings contribute to the extant literature on residential sorting in a number of ways. First, our interpretation is based on the results from entropy-based measures, which is new in New Zealand. We strongly recommend the use of entropy-based measures in future research, as along with many desirable properties, they are least sensitive to group size (Mondal et al. forthcoming). Second, this is among the first studies to consider residential sorting within and between broad ethnic groups. This is important because the broad (Level 1) ethnic groups are very heterogeneous and may not represent the characteristics and choices of their component (Level 2) groups. For instance, the ‘Asian’ broad ethnic group includes diverse Level 2 groups such as Southeast Asian, Chinese and Indian ethnicities. An argument could be made that even the Level 2 groups are too heterogeneous (e.g. Southeast Asian), and that Level three groups (Thai, Vietnamese, etc.) would be an improvement. We leave that as an exercise for future research. Previous studies in New Zealand have found that the Pacific group tends to co-locate with its own-group members the most (Johnston et al. 2011; Maré et al. 2012). However, using finer-grained (Level 2) ethnic groups we observe that although the Level 2 ethnic groups under the broad Pacific group are also highly residentially segregated, residential sorting is also relatively high among those in the MELAA group. That the conclusions change depending on the level of analysis demonstrates the importance of considering the appropriate level of ethnic aggregation. Finally, this paper is one of only a few that include occupation in studying residential sorting in New Zealand.

This study can be extended in a number of ways. In addition to using even more finer-grained ethnic groups, more complex patterns and trends in residential sorting can be identified by combining cultural and socio-economic variables through cross-tabulated groups (e.g. ethnicity-income, ethnicity-qualification, etc.). Though we find a less pronounced pattern of residential sorting by occupation, education and income than for ethnicity, further investigation of other socio-economic variables, as well as of other cultural variables like language and religion, offers also fruitful avenues for future research. Additionally, when looking at residential sorting by occupation, we only looked at individuals who are employed, and not at those who are not in the work force because they are unemployed, fulltime carers or retired. Given the ageing of the population, the study of residential (re)location of older couples and individuals is of growing importance. Moreover, rather than taking a descriptive approach there is also much scope for in-depth regression modelling of residential location, as previously explored by Maré and Coleman (2011). Finally, the consequences of current and future trends in residential sorting for individual well-being and local social capital are also a demanding but important topic for further investigation.

Notes

Data from the 2018 Census of Population and Dwellings were not yet available at the time of writing of this paper.

Pākehā are non-Māori, usually of European ethnic origin or background.

Area units are non-administrative areas that are aggregations of meshblocks. In urban areas, an area unit is similar in size to a suburb or neighbourhood (Statistics New Zealand 2013a). We use 2013 area unit boundaries.

Counts that are already a multiple of three are left unchanged, and all other counts are rounded randomly either up or down to be a multiple of three.

Refer to Appendix Table 6 for the Level 1 and Level 2 classification of ethnicities in New Zealand.

We ran the analysis also with ‘not further defined’ dropped, and again with ‘not further defined’ as a separate category. The differences in results with those reported in this paper are minimal, but available upon request to interested readers.

Specifically, the ethnicity question in the 1996 Census had a different format from that used in 1991 and 2001. In 1996, there was an answer box for 'Other European' with additional drop down answer boxes for 'English', 'Dutch', 'Australian', 'Scottish', 'Irish', and 'other'. These were not used in 1991 or 2001. Furthermore, the first two answer boxes for the question were in a different order in 1996 from 1991 and 2001. 'NZ Māori' was listed first, and 'NZ European or Pākehā' was listed second in 1996. The 1991 and 2001 questions also only used the words 'New Zealand European' rather than 'NZ European or Pākehā' (Pākehā is the Māori word referring to a person of European descent). Also, the 2001 question used the word 'Māori' rather than 'NZ Māori' (Statistics New Zealand 2017a, b, c).

Highest qualification is derived for people aged 15 years and over and combines highest secondary school qualification and post-school qualification to obtain a single highest qualification by category of attainment (Statistics New Zealand 2015).

For highest qualification, 2013 and 2006 Census data have limited comparability with 2001 Census data due to the progressive introduction of the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) from 2002. NCEA is now the main qualification for secondary school students (Statistics New Zealand 2013a).

This is the highest secondary school qualification gained by category of attainment and was collected for people aged 15 years and over (Statistics New Zealand 2015).

The Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) was only introduced in 2006.

In the Census, total personal income is collected for people aged 15 years and over, who usually live in New Zealand and are present on census night (including those who state not receiving any income). Total personal income is the before-tax income for the respondent and is collected as an income range rather than an actual dollar income (Statistics New Zealand 2015).

The detailed year-wise income bands are shown in Appendix Table 9.

We define 0*ln(0) = \( \mathop {\lim }\limits_{q \to 0} [q({ \ln }(q)] = 0 \) to allow calculation of \( D_{a} \) even in the case of there being groups who have zero members in any area at some point in time.

The income categories are listed in Appendix Table 9.

This number has declined from 2006 to 2013 because the number of people calling themselves New Zealander declined for New Zealand as a whole from 430,000 in 2006 to just under 66,000 in 2013 (Statistics New Zealand 2013a).

See Appendix Table 9.

See Appendix Table 8.

See Appendix Table 7.

The data used for the Level 1 calculation have been constructed from the Level 2 data sheets (using a bottom-up approach), so that the total population count at both levels are the same.

References

Alimi O, Maré DC, Poot J (2016) Income inequality in New Zealand regions. In: Spoonley P (ed) Rebooting the regions. Massey University Press, Auckland, pp 177–212

Alimi OB, Maré DC, Poot J (2018) More pensioners, less income inequality? The impact of changing age composition on inequality in big cities and elsewhere. N Z Popul Rev 44:49–84

Auckland Council. (2018) Auckland plan 2050, evidence report. https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/auckland-plan/about-the-auckland-plan/Evidence%20reports%20documents/evidence-report-developing-the-plan.pdf. Accessed 8 Aug 2019

Balakrishnan TR, Maxim P, Jurdi R (2005) Residential segregation and socio-economic integration of visible minorities in Canada. Migr Lett 2:126–143

Bennett PR (2011) The relationship between neighbourhood racial concentration and verbal ability: an investigation using the institutional resources model. Soc Sci Res 40:1124–1141

Betancourt H, López SR (1993) The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. Am Psychol 48:629–637

Caldwell JT, Ford CL, Wallace SP, Wang MC, Takahashi LM (2017) Racial and ethnic residential segregation and access to health care in rural areas. Health Place 43:104–112

Cameron MP, Poot J (2019) Towards superdiverse aotearoa: dimensions of past and future ethnic diversity in New Zealand and its regions. N Z Popul Rev 45:18–45

Dalziel P (2013) Education and skills. In: Rashbrooke M (ed) Inequality: a New Zealand crisis. Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, pp 184–194

Denton NA, Massey DS (1988) Residential segregation of Blacks, Hispanics and Asians by socioeconomic status and generation. Soc Sci Quart 69:797–817

Domina T (2006) Brain drain and brain gain: rising educational segregation in the United States, 1940–2000. City Community 5:387–407

Duncan OD, Duncan B (1955) Residential distribution and occupational stratification. Am J Sociol 60:493–503

Ellis M, Wright R, Parks V (2004) Work together, live apart? Geographies of racial and ethnic segregation at home and at work. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 94:620–637

Evans L, Grimes A, Wilkinson B, Teece D (1996) Economic reform in New Zealand 1984–95: the pursuit of efficiency. J Econ Lit 34(4):1856–1902

Farley R (1977) Residential segregation in urbanized areas of the United States in 1970: an analysis of social class and racial differences. Demography 14:497–518

Fathimath A (2017) Impact of municipal amalgamation on stakeholder collaboration: the case of Auckland New Zealand. Kōtuitui N Z J Soc Sci Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083x.2017.1367313

Fischer MJ (2003) The relative importance of income and race in determining residential outcomes in U.S. urban areas, 1970–2000. Urban Aff Rev 38:669–696

Florida R, Mellander C (2018) The geography of economic segregation. Soc Sci 7:123

Fong E, Hou F (2009) Residential patterns across generations of new immigrant groups. Sociol Perspect 52:409–428

Forrest J, Poulsen M, Johnston R (2006) Peoples and spaces in a multicultural nation: cultural group segregation in metropolitan Australia. Espace Popul Sociétés 1:151–164

Fowler CS, Lee BA, Matthews SA (2016) The contributions of places to metropolitan ethnoracial diversity and segregation: decomposing change across space and time. Demography 53:1955–1977

Friesen W (2008) Diverse Auckland: the face of New Zealand in the 21st Century. Asia New Zealand Foundation, Wellington. https://www.asianz.org.nz/assets/Uploads/4820390270/Diverse-Auckland-the-face-of-New-Zealand-in-the-21st-Century.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2019

Grodsky E, Pager D (2001) The structure of disadvantage: individual and occupational determinants of the Black–White wage gap. Am Sociol Rev 66:542–567

Hall M, Iceland J, Yi Y (2019) Racial Separation at Home and Work: segregation in Residential and Workplace Settings. Popul Res Policy Rev 38:671–694

Halpern-Felsher B, Connell J, Spencer M, Aber JL, Duncan G, Clifford E, Crichlow W, Usinger P, Cole S, Allen L, Seidman E (1997) Neighborhood and family factors predicting educational risk and attainment in African American and White children and adolescents. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G, Aber JL (eds) Neighborhood poverty: context and consequences for children. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 146–173

Hancock A (2015) Where have they gone? changes in occupations using 1991–2013 New Zealand census data. Statistics New Zealand, Wellington. https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/LEW/article/view/2217. Accessed 12 Jan 2019

Ho E (2015) The changing face of Asian peoples in New Zealand. N Z Popul Rev 41:95–118

Iceland J, Weinberg DH, Steinmetz E (2002) Racial and ethnic residential segregation in the United States 1980–2000, appendix B. US Census Bureau, Washington

Johnston R, Poulsen M, Forrest J (2002) Rethinking the analysis of ethnic residential patterns: segregation, isolation, or concentration thresholds in Auckland, New Zealand? Geogr Anal 34:245–261

Johnston R, Poulsen M, Forrest J (2004) The comparative study of ethnic residential segregation in the USA, 1980–2000. Tijdschr Econ Soc Ge 95:550–569

Johnston R, Poulsen M, Forrest J (2005) Ethnic residential segregation across an urban system: the Maori in New Zealand, 1991–2001. Prof Geogr 57:115–129

Johnston R, Poulsen M, Forrest J (2007) The geography of ethnic residential segregation: a comparative study of five countries. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 97:713–738

Johnston R, Poulsen M, Forrest J (2008) Asians, Pacific Islanders, and ethnoburbs in Auckland, New Zealand. Geogr Rev 98:214–241

Johnston R, Poulsen M, Forrest J (2011) Evaluating changing residential segregation in Auckland, New Zealand, using spatial statistics. Tijdschr Econ Soc Geogr 102:1–23

Johnston R, Forrest J, Jones K, Manley D (2016) The scale of segregation: ancestral groups in Sydney. Urban Geogr 37(7):985–1008

Kukutai T (2008) Ethnic self-prioritisation of dual and multi-ethnic youth in New Zealand. Statistics New Zealand, Wellington

Lee BA, Farrell CR, Reardon SF, Matthews SA (2019) From census tracts to local environments: an egocentric approach to neighborhood racial change. Spat Demogr 7:1–26

Lichter DT, Parisi D, Taquino MC (2015) Toward a new macro-segregation? Decomposing segregation within and between metropolitan cities and suburbs. Am Sociol Rev 80:843–873

Manley D, Johnston R, Jones K, Owen D (2015) Macro, meso and microscale segregation: modeling changing ethnic residential patterns in Auckland, New Zealand, 2001–2013. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 105:951–967

Manley D, Johnston R, Jones K (2019) Decomposing multi-level ethnic segregation in Auckland, New Zealand, 2001–2013: segregation intensity for multiple groups at multiple scales. Tijdschr Econ Soc Geogr 110(3):319–338

Maré DC, Coleman A (2011) Estimating the determinants of population location in Auckland. Motu Economic and Public Policy Research, Wellington. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1861531. Accessed 17 Jan 019

Maré DC, Coleman A, Pinkerton R (2011) Patterns of population location in Auckland. Motu Economic and Public Policy Research, Wellington. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1860872. Accessed 1 Dec 2018

Maré DC, Pinkerton RM, Poot J, Coleman A (2012) Residential sorting across Auckland neighbourhoods. N Z Popul Rev 38:23–54

Maré DC, Pinkerton RM, Poot J (2016) Residential assimilation of immigrants: a cohort approach. Migr Stud 4:373–401

Massey DS (1979) Effects of socioeconomic factors on the residential segregation of blacks and Spanish Americans in U.S. urbanized areas. Am Sociol Rev 44:1015–1022

Massey DS, Denton NA (1988) The dimensions of racial segregation. Soc Forces 67:281–315

Massey DS, Denton NA (1993) American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2016). Migration and labour force trends: Auckland overview 2015. New Zealand Immigration, Wellington. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/info-services/immigration/migration-research-and-evaluation/migration-and-labour-force-trends/document-and-image-library/INZ_Migrant.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2018

Mondal M, Cameron MP, Poot J (forthcoming) Group-size bias in the measurement of residential sorting (Working paper in Economics No. 9/18). University of Waikato, Hamilton

Musterd S (2005) Social and ethnic segregation in Europe: levels, causes, and effects. J Urb Aff 27(3):331–348

New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage (2015). Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. https://teara.govt.nz/en/population-change/print. Accessed 7 Aug 2019

Nijkamp P, Poot J (2015) Cultural diversity: a matter of measurement. In: Nijkamp P, Poot J, Bakens J (eds) The economics of cultural diversity. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 17–51

Pool I (1991) Te Iwi Maori. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Poot J, Pawar S (2013) Is demography destiny? Urban population change and economic vitality of future cities. J Urb Manag 2(1):5–23

Poulsen M, Johnston J, Forrest J (2004) Is Sydney a divided city ethnically? Aust Geogr Stud 42:356–377

Reardon SF, Firebaugh G (2002) Measures of multigroup segregation. Sociol Methodol 32:33–67

Reardon SF, Yun JT, Eitle TM (2000) The changing structure of school segregation: measurement and evidence of multiracial metropolitan-area school segregation, 1989–1995. Demography 37:351–364

Schelling TC (1971) Dynamic models of segregation. J Math Sociol 1:143–186

Simkus AA (1978) Residential segregation by occupation and race in ten urbanized areas, 1950–1970. Am Sociol Rev 43:81–93

Sims M (1999) High-status residential segregation among racial and ethnic groups in five metro areas, 1980–1990. Soc Sci Quart 80:556–573

Spoonley P (2014) Superdiversity, social cohesion, and economic benefits. IZA World of Labor. https://wol.iza.org/articles/superdiversity-social-cohesion-and-economic-benefits/long. Accessed 15 Nov 2018.

Statistics New Zealand (2007) Internal migration. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/Migration/internal-migration.aspx. Accessed on 15 Dec 2018

Statistics New Zealand (2013a) 2013 Census definitions and forms. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/info-about-2013-census-data/2013-census-definitions-forms/definitions.aspx. Accessed 12 Jan 2019

Statistics New Zealand (2013b) 2013 Census information by variable. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/info-about-2013-census-data/information-by-variable.aspx. Accessed 1 Jan 2019

Statistics New Zealand (2015) IDI data dictionary: 2013 census data. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/integrated-data-infrastructure/idi-data/2013-census-data.aspx. Accessed 2 Jan 2019

Statistics New Zealand (2017a) 2001 Census of population and dwellings: change in ethnicity question. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2001-census-data/change-in-ethnicity-question.aspx. Accessed 11 Jan 2019

Statistics New Zealand (2017b) GDP rises on strength in services. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/gdp-rises-on-strength-in-services. Accessed 6 Nov 2018

Statistics New Zealand (2017c) Labour force participation rate. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/nz-social-indicators/Home/Labour%20market/lab-force-particip.aspx#anchor16. Accessed October 17 2018

Statistics New Zealand (2019a) Ethnic Group (Grouped Total Responses) and Maori Descent by Sex, for the Census Usually Resident Population Count, 1991, 1996, 2001 and 2006. http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLECODE231. Accessed 7 Aug 2019

Statistics New Zealand. (2019b). Ethnic group (total responses) by age group and sex, for the census usually resident population count, 2001, 2006, and 2013 Censuses. http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLECODE8021. Accessed Aug 7 2019

Theil H (1972) Statistical decomposition analysis: with applications in the social and administrative sciences. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Theil H, Finezza AJ (1971) A note on the measurement of racial integration of schools by means of informational concepts. J Math Sociol 1:187–194

van der Pas S, Poot J (2011) Migration paradigm shifts and transformation of migrant communities: the case of Dutch Kiwis. CReAM. http://cream-migration.org/publ_uploads/CDP_12_11.pdf. Accessed 21 Sept 2018

van Mourik A, Poot J, Siegers JJ (1989) Trends in occupational segregation of women and men in New Zealand: some new evidence. N Z Econ Pap 23:29–50

Walks RA, Bourne LS (2006) Ghettos in Canada’s cities? Racial segregation, ethnic enclaves and poverty concentration in Canadian urban areas. Can Geographer/Le Géogr Can 50:273–297

Weeden KA, Grunsky DB (2005) The case for a new class map. Am J Sociol 111:141–212

White MJ (1986) Segregation and diversity measures in population distribution. Popul Index 52:198–221

White MJ, Glick JE (1999) The impact of immigration on residential segregation. In: Bean FD, Bell-Rose S (eds) Immigration and opportunity: race. Ethnicity and Employment in the United States, Russell Sage

Acknowledgements

The first author acknowledges the support provided by the University of Waikato in the form of a University of Waikato Doctoral Scholarship. This study has also been supported by the 2014–2020 Capturing the Diversity Dividend of Aotearoa New Zealand (CaDDANZ) programme, funded by Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment grant UOWX1404. We thank Robert Didham, participants at the WEAI 94th Annual Conference, held in San Francisco in June 2019, and three anonymous referees for extensive comments and suggestions that have improved the quality and clarity of the paper. We also thank Geua Boe-Gibson and Dave Maré for their help with creating the maps.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Disclaimer

The results in this paper are not official statistics. They have been created for research purposes from Census unit record data in the Statistics New Zealand Datalab. The opinions, findings, recommendations and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors, not Statistics New Zealand. Access to the anonymised data used in this study was provided by Statistics New Zealand under the security and confidentiality provisions of the Statistics Act 1975. Only people authorised by the Statistics Act 1975 are allowed to see data about a particular person, household, business, or organisation, and the results in this paper have been confidentialized to protect these groups from identification and to keep their data safe. Careful consideration has been given to the privacy, security and confidentiality issues associated with using unit record census data.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mondal, M., Cameron, M.P. & Poot, J. Cultural and economic residential sorting of Auckland’s population, 1991–2013: an entropy approach. J Geogr Syst 23, 291–330 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-020-00327-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-020-00327-1

Keywords

- Residential sorting

- Cultural sorting

- Economic sorting

- Segregation

- Entropy measures

- Cultural diversity

- Economic diversity