Abstract

The “slippery slope framework” suggests voluntary and enforced compliance as the two motivations underlying tax compliance behavior. Using questionnaire data based on a sample of 476 self-employed taxpayers we show that perceptions of procedural and distributive justice predict voluntary compliance, and trust in authorities mediates this observed relation. In addition, the relation between retributive justice, i.e. the perceived fairness with regard to the sanctioning of tax evaders, and enforced compliance was mediated by power, just as the relation between perceived deterrence of authorities’ enforcement strategies and enforced compliance. With regard to both retributive justice and deterrence also a mediational effect of trust on the relation to voluntary compliance was identified. Furthermore, voluntary and enforced compliance were related to perceived social norms, but these relations were neither mediated by trust nor power. Our findings are of particular relevance since the literature identifies self-employed taxpayers as evading considerably more taxes than employees and therefore they are an important audience for interventions to raise tax compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research on tax compliance has a long tradition in the field of economics, but in psychology it received special attention only in recent years. The classical economic position was dominated by the model proposed by Allingham and Sandmo (1972). They framed the decision to evade taxes as an individual decision under uncertainty, determined by the factors income level, tax rate, probability of detection, and penalty rate (Allingham and Sandmo 1972). Based on von Neumann and Morgenstern’s axioms for behavior under uncertainty (1947), and building on the economic theory of criminal activity (Becker 1968), the rationale is that taxpayers predominantly seek to maximize their own expected utility and thus evade if they can expect to get away with it. However, taking into account the rather low probability that a taxpayer may be audited in almost any country as well as the relatively low level of fines for evasion, the assumption that solely the level of deterrence determines whether citizens evade taxes must be seriously doubted. An overview of the inconsistent empirical findings in the literature with regard to the traditional economic factors income, tax rate, audit probability, and severity of fines is reported in Kirchler et al. (2010).

As a consequence, alternative factors like the perceived fairness of the tax system and social norms were identified as relevant influences concerning the tax honesty of citizens. The relevance of fairness issues regarding tax behavior was already recognized by Schmölders (1960), who postulated that unfair treatment in comparison to others or with respect to the benefits from public goods might be an important determinant of tax morale. Justice considerations are not relevant in the classical economic approach of deterrence. Nevertheless, different aspects of fairness and justice were found to be related to tax compliance, showing that perceived fairness with regard to governmental institutions and the tax system has a significant influence on tax morale (e.g., Calderwood and Webley 1992; Fjeldstad 2004; Tyler 2006; Wartick 1994).

Social norms relate to the acceptance of tax evasion among a relevant reference group, and a number of studies confirmed that perceived tax evasion among friends and colleagues is correlated with hypothetical as well as self-reported tax evasion (e.g., Bergmann and Nevarez 2005; Cullis and Lewis 1997; Webley et al. 2001). However, as in the case of the traditional economic factors, findings concerning rather psychological determinants of compliance have to be considered as more or less inconclusive as well (for a review see Kirchler 2007).

The “slippery slope framework” of tax compliance (Kirchler et al. 2008) offers a possibility to integrate the puzzling effects of economic and psychological factors and is widely cited in recent publications on tax behavior (e.g., Alm and McClennan 2012; Bazart and Pickhardt 2011; Durham et al. 2014). In this framework different motivations for paying taxes are differentiated: enforced and voluntary compliance. It is assumed that mainly traditional economic factors such as audit probability and fines determine perceived power of authorities to enforce compliance, whereas psychologically relevant factors such as the perception of a fair tax system and social norms affect trust in authorities resulting in voluntary cooperation. Thus, the “slippery slope framework” introduces two major dimensions which both influence the level of tax compliance: trust in authorities and power of authorities. Tax honesty can be achieved either by taking measures that increase trust or by measures to enhance power, but the resulting compliance differs in quality. The basic assumptions of the “slippery slope framework” were also formalized in an economic model (Prinz et al. 2014) and were supported by empirical research in recent years (e.g., Kogler et al. 2013; Lisi 2012; Muehlbacher et al. 2011).

In the present study, the main assumptions of the “slippery slope framework”, as well as the influence of underlying variables like fairness perceptions, social norms, and deterrence are investigated applying a questionnaire within a sample of exclusively self-employed taxpayers in Austria. Since self-employed have considerably more chances to evade taxes than employees and evidentially use these opportunities (e.g., Kleven et al. 2011; Slemrod 2007), a validation of the influence of trust and power on intentions to comply within this respective group is of special importance. In a first step, by applying regression analyses, we show that (i) trust in authorities serves as a significant predictor of the motivation to comply voluntarily, (ii) perceived power of authorities serves as a significant predictor of enforced compliance, and (iii) both trust and power are significant predictors of compliance in general, regardless of its underlying motivation.

Furthermore, we expect perceived fairness to fuel trust, and trust to mediate the effect of fairness on voluntary compliance. In accordance to established classifications in social psychology (e.g., Adams 1965; Thibault and Walker 1978; Tyler 1990) three types of fairness will be considered in our study: (i) procedural justice, (ii) distributive justice, and (iii) retributive justice. Procedural justice refers to the fairness of the process of resource distribution and other tax related decisions made by authorities. Essential components of procedural justice are neutrality of the procedures, trustworthiness of the tax authorities and respectful treatment (Tyler and Lind 1992; Murphy 2003). Actually, there is empirical evidence that high trust in authorities might serve as a boundary condition to the effectiveness of procedural fairness as an instrument to increase tax compliance (Van Dijke and Verboon 2010; Wahl et al. 2010a, b). Distributive justice concerns the exchange of resources with regard to benefits and costs of the tax system. Relevant comparisons are made on the individual, the group, and the societal level. If the tax burden is perceived to be heavier than that of comparable others, compliance is likely to decrease (Spicer and Lundstedt 1976; Juan et al. 1994). As procedural fairness, also distributive justice is assumed to affect perceived trustworthiness of tax authorities and should therefore entail a higher degree of voluntary compliance (Kirchler et al. 2008). Finally, retributive justice refers to the appropriateness of sanctions in case of an offence. Unreasonable, intrusive audits and unfair penalties are said to evoke negative attitudes towards taxes and the responsible authorities (Strümpel 1969; Wenzel and Thielmann 2006). In this vein, perceptions of lacking retributive justice will decrease trust in authorities and as a consequence affect voluntary cooperation. However, since perceptions of retributive justice also depend on detection and punishment of tax evaders, retributive justice is likely to be related to the power dimension of the “slippery slope framework”, too (Kirchler et al. 2008).

Besides fairness, social norms are assumed to fuel trust and the effect of norms on voluntary compliance should be mediated by trust and power. Possible mediation effects concerning social norms will be investigated. With regard to the “slippery slope framework”, norms are related to both, trust and power. Social norms may de- or increase trust, and, in addition they affect tax laws and the role given to authorities, which influences their power (Kirchler et al. 2008). Referring to Wenzel (2004) the relationship between social norms and tax compliance is complex. Taxpayers are assumed to internalize the social norms and act according to their respective reference group (e.g., the group of self-employed) only if they strongly identify with this group.

At last, we investigate potential mediation effects of perceived power in whether tax authorities’ deterrence strategies are effective. Deterrence corresponds to the instrumental goal of prevention of future crimes by exertion of negative sanctions. In the “slippery slope framework”, it is argued that the interpretation of fines and the target group to which fines are specifically directed matters (Kirchler et al. 2008). In an antagonistic climate, fines can be part of a “cops and robbers” game, in a synergistic climate they may be perceived as an adequate retribution for behavior that harms the community. Thus, deterrence might be connected to trust and to power. Fines that are perceived as too low could serve as an indicator that the authorities are weak and therefore undermine trust. Inappropriate high fines in case of misinterpretation of ambiguous tax laws may erode the perception of retributive justice, provoking taxpayers to try and compensate their losses by evading again.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Overall, 1,729 people were randomly selected by an institute for market research from a panel of self-employed Austrian taxpayers and were invited to participate in an online-survey in June 2008. Participation took about 40 min and for completing the questionnaire credit points were received, which could be exchanged subsequently for a 15 Euros restaurant voucher. The initial rate of return amounted to nearly 40 %, the final sample—excluding incomplete and invalid questionnaires—resulted in 476 participants (final return rate of about 28 %). The excluded participants were removed from the sample because they either turned out not to be self-employed, did not indicate to be taxpayers, or because they did not complete the questionnaire. The initial response rate of 40 % is typical of response rates for online surveys, which for instance varied between 20 and 47 % in a comparison of different survey methods (Nulty 2008).

The mean age of participants was approximately 45 years (\(\hbox {M} = 45.20\); \(\hbox {SD} = 10.48\)) and about one third of the sample were females (31.3 %). The Austrian microcensus of the year 2006 as official representative statistics of the population and the labor market in Austria indicates that the median age of Austrian self-employed falls into the category between 45 and 49 years, with a tendency to the lower bound. The percentage of self-employed women is listed as 34.9 %. Different levels of education were distributed relatively equally in the sample (25.8 % compulsory education; 38.9 % general qualification for university entrance; 35.3 % academic education). The vast majority of participants had a gross income of below € 50,000 per year (71.9 %) compared to a lower number of participants in higher income categories (€ 50,000–100,000: 19.9 %; above € 100,000: 8.2 %). Overall, the present sample can be considered as representative for self-employed taxpayers in Austria with regard to age, gender, and also concerning the respective region of residence. For education and income levels this information was not available.

2.2 Material

Besides introductory questions to check whether respondents were self-employed and had to pay taxes on income, the questionnaire consisted of three blocks of items about social identity of Austrian and of self-employed taxpayers, respectively. These scales were not used in the present study. All other scales are presented in detail below (items for all scales used in the present study can be found in the “Appendix”) and were answered on a 7-point scale (1 = strong disagreement to 7 = strong agreement). For each participant the respective items of the different scales were aggregated and subsequently scale means were calculated.

Perceived trust in tax authorities was measured by the item “The Austrian Tax Office is trustworthy”, and perceived power of tax authorities by the statement “The Austrian Tax Office has extensive means to force citizens to be honest about tax”. The different forms of compliance, voluntary and enforced compliance, were measured by two items each. The scale voluntary tax compliance consisted of the items, “I pay my tax as a matter of course” and “I would also pay my tax if there were no controls” \((\alpha = .78)\). The two items on enforced compliance were, “I pay tax because the risk of being checked is too high” and “I feel that I am forced to pay tax” \((\alpha = .70)\). These scales are adapted from a draft version of the TAX-I questionnaire (Kirchler and Wahl 2010) and similar previous studies on the “slippery slope framework” (e.g., Wahl et al. 2010a, b). The measure for general tax compliance was computed by averaging both these subscales. Hence, it captures the intention for compliance regardless of its underlying motivation. We refrained from asking openly about compliance in general, since compliance levels in surveys directly requesting compliance information are likely to be overstated due to social desirability (Andreoni et al. 1998; Elffers et al. 1987).

Perceived procedural justice was measured by 26 items (e.g., “The decision processes and tax audits of the Austrian tax administration are executed fairly”; \(\alpha = .92\)). The scale for distributive justice consisted of overall 12 items (e.g., “The amount of taxes I have to pay is fair”; \(\alpha =.93\)), in which the fairness of the tax burden had to be assessed for the individual participant, for self-employed taxpayers in Austria, and for Austrian taxpayers in general. Perceived retributive justice was measured by 6 items (e.g., “The Austrian legal system guarantees that tax evaders get the penalty they deserve”; \(\alpha =.87\)).

The 12 items of the social norms scale concerned tax related norms among self-employed taxpayers as well as among Austrian taxpayers (e.g., “In general, self-employed taxpayers have the opinion that taxes should be paid honestly on the entire income”; \(\alpha = .82\)). Finally, the deterrence scale consisted of four items (e.g., “The Austrian tax legislation guarantees that tax evaders are detained from further similar delinquencies.”; \(\alpha = .84\)). The scales assessing justice perceptions, social norms and deterrence were developed by referring to essential theoretical knowledge concerning these issues (cf. Tyler 1990; Wenzel 2004) and their wording was adapted for the specific context of the present study. As mentioned before, all scales were presented in a Likert-type form, where participants had to indicate their agreement to one or several statements on the respective issue (1 = “I completely disagree”, 7 = “I completely agree”). All variables were z-transformed before running the analyses.

3 Results

3.1 Trust and power as predictors of compliance

The analysis of the relationship between trust and power revealed a significant but low positive correlation (\(\hbox {r} = .13\); \(p < .01\)). This shows that high trust is accompanied by the perception of high power and vice versa, suggesting that perceptions of trust and power influence each other in a positive way.

Two linear regression modelsFootnote 1 were estimated to test the hypothesis that perceived trust in the tax authorities is a significant predictor of voluntary tax compliance. In model 1 the socio-demographic variables sex, age, educational level, and income as well as trust and power were included, in model 2 the interaction trust \(\times \) power was added. In the first model only trust was identified as a significant predictor of voluntary compliance. In the second model, when the interaction trust \(\times \) power was added, again only trust was significant. None of the demographic variables was significant in model 1 or in model 2. These findings are in line with the basic assumptions of the “slippery slope framework” (see Table 1 for details).

Figure 1 depicts these findings with regard to voluntary tax compliance by using local linear regression analysis. As expected, the way compliance changes as a function of trust and power resembles the theoretical relations as postulated in the “slippery slope framework”, i.e. the figure identifies trust as the main determinant of voluntary compliance.

In the next step, a similar regression analysis was run with enforced compliance as criterion. As depicted in Table 2, model 1 of the analysis revealed the socio-demographic variable gender as significant predictor of enforced compliance. Hence, women feel a stronger enforcement to pay taxes in general. In addition, model 1 showed that enforced compliance mainly depends on perceived power of authorities, but not on trust. In the second model, again gender and power were identified as significant predictors of enforced compliance, but no effect of the interaction trust \(\times \) power could be identified. Figure 2 shows the results of a local linear regression analysis on enforced compliance affirmed power as main input for enforced compliance.

With regard to general compliance, i.e. not differentiating between voluntary and enforced compliance, a regression analysis (see Table 3 for a summary) revealed a significant influence of sex and income on tax compliance in general. Thus, women and people with higher income tend to be more compliant. Furthermore, both trust and power were confirmed as significant predictors of overall compliance. No significant influence of the interaction trust \(\times \) power was found in model 2, whereas the influence of sex, income, trust and power remained stable. Nevertheless, the influence of the socio-demographic variables was clearly not as prominent compared to trust in and power of authorities.

To summarize, these results confirm the basic assumptions of the “slippery slope framework”. High trust, just as high power leads to more tax compliance, and each determinant affects different forms of compliance. Accordingly, when both—trust and power—are low, compliance decreases sharply. In contrast, the influence of demographic variables such as gender or income has to be considered as rather negligible.

3.2 Mediational effects of trust and power

In the remaining analyses trust and perceived power will be tested for mediating the impact of an array of variables which are frequently reported in the tax literature to affect compliance: Procedural justice, distributive justice, retributive justice, social norms, and deterrence measures. Each of these variables is tested for its effect on voluntary and enforced compliance, and whether the effect observed can be explained by an in- or decrease in trust and power. Hereby, in addition to the classical approach to mediation analysis by Baron and Kenny (1986), a Sobel-Test was applied.

Procedural justice In accordance with the assumptions of the “slippery slope framework”, the hypothesis that trust mediates the effect of perceived procedural fairness on voluntary cooperation was clearly confirmed. As suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986) three regression analyses with fairness, trust and voluntary compliance were computed. Regression coefficients for (i) the effect of procedural justice on voluntary compliance, (ii) the effect of procedural justice on trust, and (iii) the effect of procedural justice on voluntary compliance when including trust as a predictor are depicted in Fig. 3. Performance of a Sobel-Test approves the assumption that trust mediates the effect of procedural justice on voluntary compliance (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 5.73; \(p < .001\)). When running the same analysis with enforced compliance as criterion, no mediation effect of trust was observed (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 1.02; \(p = .31\)). Since procedural justice was not related to power \((\upbeta = .00; p = .97)\), power was rejected as a potential mediator for the relationship between procedural justice and both, voluntary and enforced compliance.

Distributive Justice. The analysis revealed that trust also mediates the relation between distributive justice and voluntary compliance. Detailed results are depicted in Fig. 4, and the mediational effect again is supported by the outcome of a Sobel-Test (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 6.21; \(p < .001\)). No mediation effect of trust concerning the relation of distributive justice and enforced compliance was found (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 0.70; \(p = .49\)), and again power had to be rejected as potential mediator for the relation between distributive justice and both compliance variables, because distributive justice was no significant predictor of power \((\upbeta = -.04; p = .45)\).

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between distributive justice and voluntary compliance as mediated by trust (\(\hbox {N} = 476\)). Note: *\(p< .05\), ***\(p<.001\); the number in parentheses indicates the standardized regression coefficient when controlling for the influence of trust

Retributive justice As explained in the introductory section, retributive justice is likely to be related to both, the trust dimension as well as the power dimension. In fact, we find that retributive justice has an effect on voluntary tax compliance via trust (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 3.88; \(p < .001\)), although retributive justice is not a significant predictor of voluntary compliance in our data \((\upbeta = .07;\,n.s.)\). In this case, it is appropriate to speak of an indirect rather than of a mediational effect (Hayes 2009; Mathieu and Taylor 2006). Figure 5 presents the indirect effect of retributive justice on voluntary compliance through trust. In contrast, no mediation or indirect effect, respectively, was found when investigating the impact of power on the relation between retributive justice and voluntary compliance, because power was no significant predictor of voluntary compliance \((\upbeta = .05; \,p = .26)\). In line with that a Sobel-Test revealed no significant result (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 1.05; \(p = .29\)).

Concerning the power dimension, an indirect effect was observed as well when perceived power was tested for mediating the relation between retributive justice and enforced compliance (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 2.59; \(p < .01\); detailed results are shown in Fig. 6). Replacing power by trust and testing if trust mediates the relation of retributive justice and enforced compliance yielded no significant result (Sobel-Test \(\hbox {statistic} = -1.35\); \(p = .18\)), mainly due to the fact that trust was no significant predictor of enforced compliance \((\upbeta =-.07;\,p = .15)\).

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between retributive justice and enforced compliance as mediated by power (\(\hbox {N} = 476\)). Note: **\(p<.01\), ***\(p< .001\); the number in parentheses indicates the standardized regression coefficient when controlling for the influence of power

Social norms As proposed in the tax literature social norms are a significant predictor of voluntary compliance \((\upbeta = .12;\,p < .01)\), while there is no relation to enforced compliance \((\upbeta =-.05;\,p=.32)\). Neither trust \((\upbeta =.01;\,p=.96)\) nor perceived power \((\upbeta =.01;\,p = .95)\) were related to social norms, and thus both have no mediational effect on the relation between social norms and voluntary compliance, as well as on the relation between social norms and enforced compliance. We will refer to these findings in the discussion.

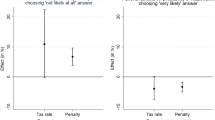

Deterrence Following theoretical considerations, the variable deterrence should not only be related to the power dimension of the “slippery slope framework”, but also to the trust dimension. Actually, deterrence is neither a significant predictor of voluntary compliance \((\upbeta = .04;\,p = .39)\), nor of enforced compliance \((\upbeta = .07;\,p = .15)\). Nevertheless, an indirect effect of trust on the relation between deterrence and voluntary compliance was observed (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 2.84; \(p < .01\); see Fig. 7 for detailed regression results). No such effect could be found when testing a potential mediation effect of power on the respective relation of deterrence and voluntary compliance (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 1.12; \(p = .26\)). As Fig. 8 shows, a mediational effect of power on the relation between deterrence and enforced compliance was found as well (Sobel-Test statistic \(=\) 3.81; \(p < .001\)). Again, the control analysis of a potential mediational effect of trust on the same relation could not be identified (Sobel-Test \(\hbox {statistic} = -1.21\); \(p = .23\)).

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between deterrence and voluntary compliance as mediated by trust (\(\hbox {N} = 476\)). Note: **\(p < .01\), ***\(p < .001\); the number in parentheses indicates the standardized regression coefficient when controlling for the influence of trust

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between deterrence and enforced compliance as mediated by power (\(\hbox {N} = 476\)). Note: **\(p < .01\), ***\(p < .001\); the number in parentheses indicates the standardized regression coefficient when controlling for the influence of power

4 Discussion

In a representative sample of self-employed taxpayers trust in the authorities was found to be a strong predictor of voluntary tax compliance, whereas power of authorities was the most prominent predictor of enforced compliance. Concerning enforced compliance, gender was observed as an additional significant determinant, showing that women feel more enforced to pay taxes than men. Regarding tax compliance in general, regardless if motivated voluntarily or by enforcement, both trust and perceived power were found to be important determinants of tax honesty.

These results are in line with other research identifying trust as the main component for explaining voluntary tax compliance, opposed to power as the main determinant of enforced compliance (Muehlbacher et al. 2011; Wahl et al. 2010a). In general, the positive effect of trust on honest tax reporting as reported in the literature was confirmed (e.g., Bergmann 2002; Murphy 2004; Torgler 2003; Torgler and Schneider 2005), just as the significant influence of audits and fines on tax payments found in other studies (e.g., Allingham and Sandmo 1972; Andreoni et al. 1998; Fischer et al. 1992). No interaction effects of trust and power were observed, a finding that is in line with other recent studies on the “slippery slope framework” either reporting no or very small interaction effects of trust and power with respect to voluntary, enforced, and general tax compliance (Kogler et al. 2013; Muehlbacher et al. 2011). In general, interaction effects of trust and power might most likely depend on the perception of authorities’ power: if sanctions are interpreted as legitimate, even a positive reinforcement of trust and power can be expected. In case of perceiving power as coercive, a stronger feeling of enforcement could lead to the counterintentional effect of decreasing trust (Hofmann et al. 2014).

In our sample of self-employed taxpayers, trust mediates the relation between procedural justice and voluntary compliance, just as well as the relation between distributive justice and voluntary compliance. Since trust as an important precondition for voluntary tax compliance may not be susceptible directly, enhancing procedural and distributive fairness seems to be a possibility for authorities to increase tax compliance. In addition, an indirect mediational effect of both, trust on the relation between retributive justice and voluntary compliance, as well as power on the relation between retributive justice and enforced compliance was found. Thus, it might be possible to influence perceptions of trust and power by changing the prevailing impression of retributive justice. An explanation for the finding that perceptions of retributive justice seem to have no direct effect on compliance might be the fact that retributive justice is interpreted as mainly concerning other taxpayers, not oneself. Referring to deterrence, again an indirect effect of both trust and power could be observed, which may be interpreted as an opportunity to affect tax payments by measures of deterrence either via trust or by power. An explanation for the absence of a direct impact of deterrence on intentions to comply could once again be explained by the feeling that deterrence is directed first and foremost against others. No mediational effect was found with regard to social norms. Social norms are a significant predictor of both, voluntary and enforced compliance, but seem to be related to neither trust nor power. These findings may be best interpreted by assuming that social norms influence tax payments directly, but are—at least in our study—not directly related to the perception of trust in and power of authorities. It is important here to differentiate between institutional and interpersonal trust (Alm et al. 2012), because social norms might predominantly be connected to trust in other citizens rather than to trust in authorities, which was measured in the present study.

Limitations of the study lie in its methodological approach. First, participation in the study was voluntary which may have introduced a bias (Alm 1991). For instance, if mainly compliance-minded subjects with high trust in authorities and a predominant motivation of voluntary compliance followed the invitation to participate in the study, it seems questionable whether our observations are generalizable to the whole population of self-employed taxpayers. Second, drawing on self-reports when studying tax behavior has often been criticized (e.g., Elffers et al. 1987; Gërxhani 2007). Accordingly, our measures for voluntary and enforced compliance may be biased by social-desirability, i.e. that admitting to pay taxes solely due to audits and fines might be harder for participants than indicating to comply voluntarily due to the feeling of a moral obligation.

Altogether, the results suggest that power of authorities and trust in authorities both are relevant factors to influence compliance of self-employed taxpayers. Since this group of taxpayers not only has the opportunity to evade taxes, but also is suspicious of making use of this opportunity, the present findings suggest important policy implications: A tax policy based solely on deterrence may not only evoke an enforced form of compliance, but should also be associated with more effort and higher expenses on the side of the tax administration. Thus, besides aiming to enforce those who are unwilling to contribute, a service-oriented tax administration also relying on trust-building measures by emphasizing procedural, distributive, and retributive fairness in order to increase and maintain voluntary compliance is absolutely necessary.

Notes

To check for robustness, all analyses presented in the following were repeated by dichotomizing the dependent variable through a median split and running logistic regression. Results remain exactly the same.

References

Adams JS (1965) Inequity in social exchange. In: Berkowitz L (ed) Advances in experimental and social psychology. Academic Press, New York

Allingham M, Sandmo A (1972) Income tax evasion: a theoretical analysis. J Public Econ 1(3–4):323–338

Alm J (1991) A perspective on the experimental analysis of taxpayer reporting. Account Rev 66:577–593

Alm J, McClennan C (2012) Tax morale and tax compliance from the firm’s perspective. Kyklos 65:1–17

Alm J, Kirchler E, Muehlbacher S, Gangl K, Hofmann E, Kogler C, Pollai M (2012) Rethinking the research paradigms for analysing tax compliance behaviour. CESifo Forum 13(2):33–40

Andreoni J, Erard B, Feinstein JS (1998) Tax compliance. J Econ Lit 36(4):818–860

Baron AM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Social Psychol 51:1173–1182

Bazart C, Pickhardt M (2011) Fighting income tax evasion with positive rewards. Public Finance Rev 31:124–149

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ 76:169–217

Bergmann M (2002) Who pays for social policy? A study on taxes and trust. J Social Policy 31:289–305

Bergmann M, Nevarez A (2005) The social mechanisms of tax evasion and tax compliance. Politica y Gobierno 12:9–40

Calderwood G, Webley P (1992) Who responds to changes in taxation? The relationship between taxation and incentive to work. J Econ Psychol 13:735–748

Cullis J, Lewis A (1997) Why people pay taxes: from a conventional economic model to a model of social convention. J Econ Psychol 18:305–321

Durham Y, Manly TS, Ritsema C (2014) The effects of income source, context, and income level on tax compliance decisions in a dynamic experiment. J Econ Psychol 40:220–232

Elffers H, Weigel RH, Hessing DJ (1987) The consequences of different strategies for measuring tax evasion behavior. J Econ Psychol 8:311–337

Fischer CM, Wartick M, Mark MM (1992) Detection probability and taxpayer compliance: a review of the literature. J Account Lit 11:1–46

Fjeldstad O-H (2004) What’s trust got to do with it? Non-payment of service charges in local authorities in South Africa. J Mod Afr Stud 42(4):539–562

Gërxhani K (2007) “Did you pay your taxes?” How (not) to conduct tax evasion surveys in transition countries. Social Indic Res 80:555–581

Hayes AF (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 76:408–420

Hofmann E, Gangl K, Kirchler E, Stark J (2014) Enhancing tax compliance through coercive and legitimate power of tax authorities by concurrently diminishing or facilitating trust in tax authorities. Law Policy 36:290–313

Juan A, Lasheras MA, Mayo R (1994) Voluntary tax compliant behavior of Spanish income tax payers. Public Finance 49:90–105

Kirchler E (2007) The economic psychology of tax behaviour. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kirchler E, Hoelzl E, Wahl I (2008) Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: the “slippery slope” framework. J Econ Psychol 29(2):210–225

Kirchler E, Muehlbacher S, Kastlunger B, Wahl I (2010) Why pay taxes: a review on tax compliance decisions. In: Alm J, Martinez-Vasquez J, Torgler B (eds) Developing alternative frameworks for explaining tax compliance. Routledge, London, pp 15–32

Kirchler E, Wahl I (2010) Tax compliance inventory TAX-I: designing an inventory for surveys of tax compliance. J Econ Psychol 31:331–346

Kleven H, Knudsen M, Kreiner CT, Pedersen S, Saez E (2011) Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a tax audit experiment in Denmark. Econometrica 79:651–692

Kogler C, Batrancea L, Nichita A, Pantya J, Belianin A, Kirchler E (2013) Trust and power as determinants of tax compliance: testing the assumptions of the slippery slope framework in Austria, Hungary, Romania and Russia. J Econ Psychol 34:169–180

Lisi G (2012) Testing the slippery slope framework. Econ Bull 32:1369–1377

Mathieu JE, Taylor SR (2006) Clarifying conditions and decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. J Organ Behav 27:1031–1056

Muehlbacher S, Kirchler E, Schwarzenberger H (2011) Voluntary versus enforced compliance: empirical evidence for the “slippery slope” framework. Eur J Law Econ 32:89–97

Murphy K (2003) An examination of taxpayers’ attitudes towards the Australian tax system: findings from a survey of tax scheme innvestors. Aust Tax Forum 18:209–242

Murphy K (2004) The role of trust in nurturing compliance: a study of accused tax avoiders. Law Human Behav 28:187–209

Nulty DD (2008) The adequacy of resonse rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess Eval High Educ 33:301–314

Prinz A, Muehlbacher S, Kirchler E (2014) The slippery slope framework on tax compliance: an attempt to formalization. J Econ Psychol 40:20–34

Schmölders G (1960) Das Irrationale in der öffentlichen Finanzwirtschaft. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main

Slemrod J (2007) Cheating ourselves: the economics of tax evasion. J Econ Perspect 21:25–48

Spicer MW, Lundstedt SB (1976) Understanding tax evasion. Public Finance 21:295–305

Strümpel B (1969) The contribution of survey research to public finance. In: Peacock AT (ed) Quantitative analysis in public finance. Praeger, New York, pp 13–22

Thibault J, Walker L (1978) A theory of procedure. Calif Law Rev 66:541–566

Torgler B (2003) Tax morale, rule-governed behaviour and trust. Const Polit Econ 14:119–140

Torgler B, Schneider F (2005) Attitudes towards paying taxes in Austria: an empirical analysis. Empirica 32:231–250

Tyler TR (1990) Why people obey the law: procedural justice, legitimacy, and compliance. Yale University Press, New Haven

Tyler TR (2006) Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Ann Rev Psychol 57:375–400

Tyler TR, Lind E (1992) A relational model of authority in groups. In: Zanna MP (ed) Advances in experimental social psychology, vol XXV. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp 115–191

Van Dijke M, Verboon P (2010) Trust in authorities as a boundary condition to procedural fairness on tax compliance. J Econ Psychol 31:80–91

Von Neumann J, Morgenstein O (1947) Theory of games and economic behavior, 2nd edn. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Wahl I, Kastlunger B, Kirchler E (2010a) Trust in authorities and power to enforce tax compliance: an empirical analysis of the “slippery slope framework“. Law Policy 32(4):383–406

Wahl I, Muehlbacher S, Kirchler E (2010b) The impact of voting on tax payments. Kyklos 63(1):144–158

Wartick M (1994) Legislative justification and the perceived fairness of tax law changes: a reference cognitions theory approach. J Am Tax Assoc 16:106–123

Webley P, Cole M, Eidjar O-P (2001) The prediction of self-reported and hypothetical tax-evasion: evidence from England, France and Norway. J Econ Psychol 22:141–155

Wenzel M (2004) An analysis of norm processes in tax compliance. J Econ Psychol 25:213–228

Wenzel M, Thielmann I (2006) Why we punish in the name of justice: just desert versus value restoration and the role of social identity. Soc Justice Res 19:450–470

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Questionnaire items (translated from German)

Check items

-

Are you obtaining any income from a self-employed occupation?

-

Do you have to pay income tax in Austria?

Trust in authorities

-

The Austrian Tax Office is trustworthy

Power of authorities

-

The Austrian Tax Office has extensive means to force citizens to be honest about tax

Voluntary tax compliance

-

I pay my tax as a matter of course

-

I would also pay my tax if there were no controls

Enforced tax compliance

-

I pay tax because the risk of being checked is too high

-

I feel that I am forced to pay tax

Procedural justice

-

The decision processes and tax audits of the Austrian tax administration...

-

... are executed fairly

-

... are always conducted in the same manner

-

... are arbitrary (reversed)

-

... are based on facts and not on opinions

-

... make it easy to appeal against a decision

-

... in the end serve for the benefit of all

-

... respect the rights of the citizens

-

I personally have the possibility to discuss my situation with the Austrian Tax Office

-

I personally have a voice in the taxation laws and in tax issues

-

The self-employed have the possibility to discuss their situation with the Austrian Tax Office

-

The self-employed have a voice in the taxation laws and in tax issues

-

The Austrians have the possibility to discuss their situation with the Austrian Tax Office

-

The Austrians have a voice in the taxation laws and in tax issues

-

The employees of the tax administration...

-

... provide willingly information in case of any questions

-

... conceal important information (reversed)

-

... inform taxpayers adequately

-

... are friendly

-

... treat taxpayers respectfully

-

... are trying to put taxpayers off concerning tax issues (reversed)

-

... deal with administrative decisions in time

-

... take their time for the requests of the taxpayers

-

... treat all taxpayers fair

-

... treat me the same as all the others

-

... treat me fair

-

... treat self-employed the same as all the others

-

... treat self-employed fair

Distributive justice

-

The amount of taxes I have to pay is fair

-

The extent of benefits I get from the state is just compared to others

-

Related to the amount of taxes I have to pay, the state of Austria provides me equivalent benefits in return

-

The possibilities to reduce my tax load are just in comparison to the possibilities of others

-

The amount of taxes self-employed have to pay is fair

-

The extent of benefits self-employed get from the state is just compared to others

-

Related to the amount of taxes self-employed have to pay, the state of Austria provides them equivalent benefits in return

-

The possibilities of self-employed to reduce their tax load are just in comparison to the possibilities of others

-

The Austrian tax system distributes the tax load among all taxpayers in a just way

-

The Austrian state distributes the benefits from tax revenues in a just way

-

Altogether, the relation between benefits from the state and the tax due is just

-

The possibilities to reduce the tax burden are distributed among all taxpayers in a just way

Retributive justice

-

The Austrian legal system guarantees that tax evaders...

-

... get the penalty they deserve

-

... are punished appropriately regarding their offense

-

... have to atone for their act

-

... get a punishment that affects them

-

... are not treated too mildly

-

... are punished rigorously

Social norms

-

In general, self-employed have the opinion that...

-

... taxes should be paid honestly on the entire income

-

... smaller incomes can be left out of the tax declaration (reversed)

-

... loopholes in the tax legislation should be exploited (reversed)

-

... skilled manual work can be done without a bill (reversed)

-

... only real expenditures should be mentioned in the tax declaration

-

... travel expenses for private trips can be stated in the tax declaration (reversed)

-

In general, Austrians have the opinion that...

-

... taxes should be paid honestly on the entire income

-

... smaller incomes can be left out of the tax declaration (reversed)

-

... loopholes in the tax legislation should be exploited (reversed)

-

... skilled manual work can be done without a bill (reversed)

-

... only real expenditures should be mentioned in the tax declaration

-

... travel expenses for private trips can be stated in the tax declaration (reversed)

Deterrence

-

The Austrian tax legislation guarantees that tax evaders...

-

... are detained from further similar delinquencies

-

... are deterred from repeating evasion in the future

-

The Austrian tax legislation guarantees that Austrians...

-

... are detained from evading taxes

-

... are deterred from evading taxes

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kogler, C., Muehlbacher, S. & Kirchler, E. Testing the “slippery slope framework” among self-employed taxpayers. Econ Gov 16, 125–142 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-015-0158-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-015-0158-9