Abstract

Although a large number of studies have examined possible differences in cognitive performance between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD), the data in the literature are conflicting. The aims of this study were to analyze the neuropsychological pattern of subjects affected by degenerative dementia without evidence of small vessel pathology (DD) and small vessel VaD subjects in the early stages and to investigate differences in the progression of cognitive impairment. Seventy-five patients with probable VaD and 75 patients with probable DD were included. All the subjects underwent a standard neuropsychological evaluation, including the following test: Visual Search, Attentional matrices, Story Recall, Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices, Phonological and Semantic Verbal Fluency, Token, and Copying Drawings. The severity of cognitive impairment was stratified according to the MMSE score. Fifteen subjects with probable DD and 10 subjects with probable VaD underwent a 12-month cognitive re-evaluation. No significant difference was found between DD and VaD subjects in any of the neuropsychological tests except Story Recall in the mild cognitive impairment (P < 0.001). The re-test value was significantly worse than the baseline value in the MMSE (P = 0.037), Corsi (P = 0.041), Story Recall (P = 0.032), Phonological Verbal Fluency (P = 0.02), and Copying Drawings (P = 0.043) in DD patients and in the Visual Search test (P = 0.036) in VaD subjects. These results suggest that a neuropsychological evaluation might help to differentiate degenerative dementia without evidence of small vessel pathology from small vessel VaD in the early stages of these diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) account for the majority of dementia cases among elderly people [1]. Diagnosis of these disorders is essential to be able to provide appropriate pharmacological treatment and make a correct prognosis. Making a diagnosis is a multidimensional process based on medical history, neuroimaging, and behavioural observations, but it relies primarily on a neuropsychological assessment. This is especially so in the early stages of disease. Nevertheless, the differential diagnosis between the two pathologies is a highly challenging task. Although AD and VaD have traditionally been considered to result from different etiologies, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that the two diseases share common pathogenic mechanisms. For instance, epidemiological data show that the canonical vascular risk factors are associated with both VaD and AD [2]. Furthermore, neuropathological data reveal an overlap between cerebrovascular disease and markers of AD in approximately 40 % of all post-mortem examinations [3, 4]. Finally, there may be similarities in the clinical presentation, as both AD and VaD unveil cognitive deterioration, functional impairment, and behavioural symptoms [5].

Although a large number of studies have examined possible differences in cognitive performance between AD and VaD, the data in the literature are conflicting. The most consistent findings suggest that AD is characterised by a greater impairment in episodic memory, whereas patients with VaD display greater deficits in executive/attentional abilities [6, 7]. Other studies have instead found marked executive functioning and working memory impairments in patients with mild-moderate AD and VaD, with no differences being observed between the two diseases [8, 9]. The main reason for these discrepant results likely relies on differences in study populations, arising from different enrolment criteria, patients’ demographic characteristics and severity of the illness. A further source of uncertainty relies in the inherent variability associated with the definition of VaD. VaD typically refers to cognitive and behavioural disorders associated with different cerebrovascular diseases, i.e., small vessel disease, multi-infarct disease, or strategic vascular lesions. The last two pathologies express a variety of cognitive dysfunctions, which depends on the site and extent of the damage, whereas in small vessel VaD, the most prominent type of cognitive impairment is a dysexecutive syndrome [10]. However, the executive dysfunctions can also be present in AD patients, under a variety of different patterns, depending on their vascular involvement [11–13]. It is, therefore, an unsettled issue whether degenerative dementia without evidence of small vessel pathology (DD) and small vessel VaD present distinct clinical features.

The main aim of this study was to analyze the neuropsychological pattern of DD and small vessel VaD subjects in the early stages of disease by assessing two groups of patients, whose demographic characteristics and disease severity were matched. The secondary aim was to investigate differences in the progression of cognitive impairment between the two diseases as well as to assess the role of vascular risk factors. We hypothesized that in the early phase of cognitive impairment, there are differences between small vessel VaD and DD in both the neuropsychological pattern and cognitive progression.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We identified that, from a series of 278 consecutive outpatients referred to the Neuropsychological Service of the Dementia Center of Sant’Andrea Hospital (Rome, Italy), 83 patients with probable VaD (29.86 %) diagnosed according to the NINDS-AIREN criteria [14]. The diagnostic procedures included a neurological and neuropsychological evaluation, neuroimaging study (CT or MRI), routine blood analysis, thyroid function, homocysteine, vitamin B12, folate, and electroencephalogram. Single-Photon-Emission-Computerized Tomography was performed in some patients. The remaining 195 patients were diagnosed with the following diseases: 131 patients with probable DD (47.12 %), 27 with mixed dementia (9.71 %), 25 with probable FTD (8.99 %), and 12 with dementia and extrapyramidal diseases (4.32 %) (Fig. 1).

Eight of the 83 patients with probable VaD displayed strategic or multi-infarct lesions at the neuroimaging evaluation and were thus excluded from the data analysis. Seventy-five patients with probable VaD were consequently included in the study, in which they were matched for age and education level with 75 patients affected by DD. If a VaD patient matched more than one DD patient, the closest age was adopted as the decisive factor. DSM-IV TR criteria were used for the clinical diagnosis of dementia [15]. None of the subjects had other neurological or psychiatric disorders, hearing or vision impairments, severe metabolic disturbances, or a history of alcohol or drugs abuse or of head injury.

Procedure

All the subjects underwent a standard neuropsychological evaluation used as a screening tool in our center. Global cognitive functioning was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [16], whereas other areas of cognition were investigated by means of the following tests: selective attention (Visual Search—Attentional matrices) [17], episodic long-term memory (Story Recall test) [18], non-verbal logical reasoning and problem-solving ability (Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices) [19, 20], word generation by phonological and semantic cues (Phonological and Semantic Verbal Fluency test) [18, 21], auditory comprehension of complex sentences (Token test) [17, 22], and spatial abilities and constructional praxis (Copying Drawings) [17, 23]. The raw scores of each test were adjusted for age and education according to the distribution of Italian normative data.

The severity of cognitive impairment was stratified according to the MMSE score as follows: subjects with an MMSE score ≥21 were defined as mild, whereas subjects with an MMSE score ≤20 were defined as moderate.

Fifteen subjects with DD and ten subjects with probable VaD underwent a cognitive re-evaluation based on the same neuropsychological battery after 1 year (Fig. 1). The low number of re-tested subjects was due to many reasons, such as behavioural problems, appearance of new comorbidities, relatives/caregivers not available, and severity of cognitive deficit. In re-test patients, the presence/absence of six vascular risk factors and of an internal carotid stenosis were evaluated as follows: (1) arterial hypertension: history of blood pressure values higher than 160/95 mmHg or antihypertensive medication intake; (2) hypercholesterolaemia: serum cholesterol level over 220 mg/dl or statin intake; (3) hypertriglyceridaemia: serum triglyceride level over 140 mg/dl; (4) diabetes mellitus: plasma glucose level over 110 mg/dl or anti-diabetic drug intake; (5) heart disease: previous myocardial infarction or electrocardiographic evidence of atrial fibrillation; (6) smoking: more than five cigarettes per day for at least 5 years; non-smoking: less than five cigarettes per day or stopped smoking at least 10 years before; and (7) internal carotid stenosis: stenosis exceeding 30 % of at least one internal carotid on Doppler ultrasound examination.

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 13.0). Any differences between DD and VaD patients in the demographic characteristics, MMSE score, and neuropsychological performance were analyzed using t test for independent samples. Neuropsychological scores, excluding the MMSE score, were also treated as categorical variables rather than continuous variables and dichotomized for each test between impaired performance and normal performance according to the cutoff for Italian normative data; in this last case, the performance of DD and VaD patients was compared using χ 2 test.

Neuropsychological test and re-test scores were compared using the paired t test. Spearman’s non-parametric rank correlation was used to assess any correlation between the neuropsychological values in the re-test examination and the presence/absence of vascular risk factors. Finally, any differences in the presence/absence of vascular risk factors in the two subject groups were evaluated by Chi-square and Fischer’s exact tests. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

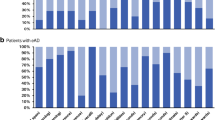

The demographic and neuropsychological characteristics of the whole sample are summarized in Table 1. The mean MMSE score was similar in the two groups (mean value ± SD: 24.4 ± 4.1 in DD patients and 24.3 ± 4.9 in VaD patients). Mild cognitive impairment (MMSE ≥ 21) was present in 62 subjects in each of the groups, whereas the remaining 13 subjects in each group displayed a moderate cognitive impairment (MMSE ≤ 20).

No significant difference was found between DD and VaD subjects in any of the neuropsychological tests except Story Recall (mean value ± SD: 5.5 ± 3.9 vs 8.4 ± 5.1, respectively; P = 0.0001) (Table 1). Furthermore, the percentage of patients, whose performance was impaired in the Story Recall test, was higher in DD subjects (65 %) than in VaD subjects (28 %) (P = 0.001; Chi-square test).

In keeping with the severity of cognitive impairment, DD subjects with mild cognitive impairment performed worse in the Story Recall test than VaD subjects (mean value ± SD: 6.08 ± 4.48 vs 9.08 ± 4.57; P < 0.001); by contrast, no differences emerged between DD and VaD subjects with moderate cognitive impairment.

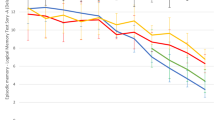

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics and the MMSE score at baseline of both the subjects who underwent and of those who did not undergo the 12-month neuropsychological re-evaluation. The only difference that emerged was in the MMSE score, which was higher in subjects who were re-evaluated in both the groups. In DD patients, the mean re-test value was significantly worse than the mean baseline value in the following tests: MMSE (P = 0.037), Corsi (P = 0.041), Story Recall test (P = 0.032), Phonological Verbal Fluency test (P = 0.02), and Copying Drawings (P = 0.043); the only significant worsening in the VaD subjects was instead detected in the Visual Search test (P = 0.036) (Table 3).

The presence of vascular risk factors was higher in VaD than in DD subjects, though the difference did not attain statistical significance (Table 4). In DD subjects, the number of vascular risk factors was correlated with the drop in the MMSE score (r = 0.711, P = 0.003; Spearman’s correlation), though not with the drop in each neuropsychological test at the 12-month follow-up. Finally, no correlation was detected between the number of vascular risk factors and either overall or specific cognitive decline in VaD subjects.

Discussion

Our results show that in the early phase of cognitive decline, Story Recall scores were significantly worse in dementia patients without evidence of small vessel pathology than in those with small vessel VaD. The Story Recall test provides one of the most reliable neuropsychological assessments for episodic long-term verbal memory function and is widely used in clinical settings. Some studies have consistently shown that medial temporal lobe and cortical-subcortical frontal structures interact in the long-term memory [24, 25]. A storage (or retention) failure is caused by damage to medial temporal structures, whereas a retrieval failure is caused by a frontal-subcortical dysfunction [26]. In processing the episodic long-term memory, when storage is efficient, the inherent organization of prose material can facilitate the encoding and retrieval of the cognitive operation. By contrast, when storage is impaired, performance in the Story recall test is invariably compromised [27]. This is indeed what we observed in our DD patients. This finding can be explained by neuropathological changes that prevalently occur in medial temporal regions in the early stages of AD. A storage failure in episodic long-term memory in the early AD is consequently not surprising [28, 29]. In our study, all the subjects with VaD had small vessel cerebrovascular disease, with changes in white matter being responsible for the subcortical brain damage. Although this damage is as severe as to cause a general cognitive impairment and to yield a clinical diagnosis of dementia, it does not affect the medial temporal lobe either so early or to such a selective degree. This explains the preserved memory storage that we observed in our VaD subjects. In keeping with the findings of the previous studies, we may hypothesize that, in the early stages of the disease, small vessel vascular dementia subjects compensate for any failure in retrieval when tested by means of the Story Recall test more effectively than DD patients [30].

Another interesting observation emerges from the analysis of the 12-month neuropshycological follow-up. DD subjects displayed a faster cognitive decline than VaD subjects in most of the tasks, which suggests that all the cognitive domains are rapidly involved. By contrast, VaD subjects perform more stably when compared with their baseline values in all the tests except Visual Search, which consists of an attentive task that measures a person’s ability to select a target within a visual scanning context. According to the most recent neuropsychological theories, attention is a complex system that presides over a number of distinct neuronal circuits. Three largely disparate attentional control systems have been identified: alerting, orienting, and executive control. Although these systems interact in many practical contexts, they are to a certain degree functionally and anatomically independent [31]. According to Posner’s theory, Visual Search can be conceptualized as an orienting task, and more specifically as the process of selecting information from sensory input [32], which is activated by a cortico-subcortical network involving the pulvinar, superior colliculus, superior parietal lobe, and frontal eye fields [33]. These neural structures contribute to the representation of spatial awareness as a component of the dorsal pathway that connects visual cortex areas to the frontal lobe [34]. In our VaD subjects, the rapid decline in the attention domain may be explained by the involvement of cerebral white matter. As all our VaD patients had small vessel disease associated with marked subcortical ischemic vascular involvement of cerebral white matter, we may hypothesize that the rapid decline in attention was caused by the interruption in the fronto-subcortical networks. This hypothesis is supported by the recent MRI studies in which an association was found between the impairment in the frontal-parietal-subcortical network and the decline in executive functions [35, 36].

In keeping with the findings of the previous studies, our data suggest that vascular risk factors may exacerbate the cognitive decline in subjects affected by dementia [37, 38]. We found a positive correlation between the number of vascular risk factors and the reduced MMSE score in DD subjects. Vascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia, are known to target the neurovascular unit, upon which they exert a deleterious effect. This effect causes neurovascular dysfunction and increases the brain’s susceptibility to injury by altering the regulation of the cerebral blood supply, by disrupting the blood brain barrier function, and by reducing the trophic support and the potential repair of the injured brain [39]. We cannot explain the lack of correlation between the vascular risk factors and cognitive decline in our VaD patients. One reason may be the small sample size used in our study. However, Pavlovic et al. recently reported, in keeping with the results of other studies, that the cognitive decline in patients with small vessel disease is related to the severity of white matter hyperintensity, and not to vascular risk factors [40]. Therefore, in contrast to AD, we cannot exclude that neurovascular function in small vessel VaD is so highly damaged that vascular risk factors do not exert any effect on cognitive decline.

Although our study has certain limitations, such as the small sample size and the short follow-up, the results that we obtained are supported by a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests and by closely matched groups of patients. These results suggest that a neuropsychological evaluation helps to differentiate degenerative dementia without evidence of small vessel pathology from small vessel VaD in the early stages of these diseases when cognitive impairments are not yet severe. In these stages, episodic verbal memory function is impaired to a greater extent in dementia patients without evidence of small vessel pathology than in those with small vessel VaD. Furthermore, our results suggest that cognitive decline progresses at different speeds in these two diseases: progression is faster in DD than in small vessel VaD and is only influenced by the presence of vascular risk factors in DD. Further research on the comparative neuropsychological evaluation of dementia patients without evidence of small vessel pathology and VaD patients affected by small vessel diseases is required to shed more light on the neuropsychological pattern in the early phases of these two diseases. Future studies should be based on a large sample size, careful characterization of patients, and MRI evaluation.

References

Wiesmamann M, Kiliaan AJ, Claassen JA (2013) Vascular aspects of cognitive impairment and dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33(11):1696–1706

Iadecola C (2010) The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol 120(3):287–296

Esiri MM, Joachim C, Sloan C, Christie S, Agacinski G, Bridges LR, Wilcock GK, Smith AD (2014) Cerebral subcortical small vessel disease in subjects with pathologically confirmed Alzheimer disease: a clinicopathologic study in the Oxford Project to Investigate Memory and Ageing (OPTIMA). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 28(1):30–35

Attems J, Jellinger KA (2014) The overlap between vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease—lessons from pathology. BMC Med 12:206

Kalaria R (2002) Similarities between Alzheimer’s Disease and vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 203–204:29–34

Hampstead BM, Libon DJ, Moelter ST, Swirsky-Sacchetti T, Scheffer L, Platek SM, Chute D (2010) Temporal order memory differences in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 32(6):645–654

Kandiah N, Narasimhalu K, Lee J, Chen CL (2009) Differences exist in the cognitive profile of mild Alzheimer’s disease and subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 27(5):399–403

McGuinness B, Barrett SL, Craig D, Lawson J, Passmore AP (2010) Executive functioning in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 25(6):562–568

Voss SE, Bullock RA (2004) Executive function: the core feature of dementia? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 18(2):207–216

Cavalieri M, Enzinger C, Petrovic K, Pluta-Fuerst A, Homayoon N, Schmidt H, Fazekas F, Schmidt R (2010) Vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease—are we in a dead-end road? Neurodegener Dis 7:122–126

Stokholm J, Vogel A, Gade A, Waldemar G (2006) Heterogeneity in executive impairment in patients with very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 22(1):54–59

Clark RL, Schiehser DM, Weissberger GH, Salmon DP, Delis DC, Bondi MW (2012) Specific measures of executive function predict cognitive decline in older adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 18(1):118–127

Reed BR, Mungas DM, Kramer JH, Ellis W, Vinters HV, Zarow C, Jagust WJ, Chui HC (2007) Profiles of neuropsychological impairment in autopsy-defined Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease. Brain 130(Pt 3):731–739

Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, Amaducci L, Orgogozo JM, Brun A, Hofman A (1993) Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN international workshop. Neurology 43(2):250–260

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington (Text revision)

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198

Spinnler H, Tognoni G (1987) Standardizzazione e taratura italiana di test neurpsicologici. Ital J Neurol Sci Suppl. 8:1–120

Novelli G, Papagno C, Capitani E, Laiacona M, Cappa SF, Vallar G (1986) Tre test clinici di memoria verbale a lungo termine: taratura su soggetti normali. Archo Psicol Neurol Psichiat 47:278–296

Raven JC (1941) Standardization of progressive matrices. Br J Med Psychol 19(1):137–150

Basso A, Capitani E, Laiacona M (1987) Raven’s coloured progressive matrices: normative values on 305 adult normal controls. Funct Neurol 2(2):189–194

Borkowski JG, Benton AL, Spreen O (1967) Word fluency and brain damage. Neuropsychologia 5(2):135–140

De Renzi E, Vignolo LA (1962) The token test: a sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain 85:665–678

Benton AL (1969) Development of a multilingual aphasia battery. Progress and problems. J Neurol Sci 9(1):39–48

Bergmann HC, Rijpkema M, Fernández G, Kessels RP (2012) Distinct neural correlates of associative working memory and long-term memory encoding in the medial temporal lobe. Neuroimage 63(2):989–997

Jeneson A, Squire LR (2011) Working memory, long-term memory, and medial temporal lobe function. Learn Mem 19(1):15–25

Pasquier F (1999) Early diagnosis of dementia: neuropsychology. J Neurol 246(1):6–15

Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW (2004) Neuropsychological assessment, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 444–448

Traykov L, Baudic S, Raoux N, Latour F, Rieu D, Smagghe A, Rigaud AS (2005) Patterns of memory impairment and perseverative behavior discriminate early Alzheimer’s disease from subcortical vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 229–230:75–79

Sarazin M, Berr C, De Rotrou J, Fabrigoule C, Pasquier F, Legrain S, Michel B, Puel M, Volteau M, Touchon J, Verny M, Dubois B (2007) Amnestic syndrome of the medial temporal type identifies prodromal AD. Neurology 69(19):1859–1867

Moorhouse P, Rockwood K (2008) Vascular cognitive impairment: current concepts and clinical developments. Lancet Neurol 7(3):246–255

Posner MI, Fan J (2008) Attention as an organ system “Attention as an organ system”. In: Pomerantz JR (ed) Topics in integrative neuroscience: from cells to cognition. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 31–61

Eimer M (2014) The neural basis of attentional control in visual search. Trends Cogn Sci 18(10):526–535

Raz A (2004) Anatomy of attentional networks. Anat Rec B New Anat 281(1):21–36

Karnath HO (2001) New insights into the functions of the superior temporal cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci 2(8):568–576

Jacobs HI, Visser PJ, Van Boxtel MPJ (2012) The association between white matter hyperintensities and executive decline in mild cognitive impairment in network dependent. Neurobiol Aging 33(1):201

Parks CM, Iosif AM, Farias S, Reed B, Mungas D, DeCarli C (2011) Executive function mediates effects of white matter hyperintensities on episodic memory. Neuropsychologia 49(10):2817–2824

Blom K, Emmelot-Vonk MH, Koek HL (2013) The influence of vascular risk factors on cognitive decline in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Maturitas 76(2):113–117

O’Brien JT, Markus HS (2014) Vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med 12:218

Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D, Petersen RC, Seshadri S (2011) Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 42(9):2672–2713

Pavlovic AM, Pekmezovic T, Tomic G, Trajkovic JZ, Sternic N (2014) Baseline predictors of cognitive decline in patients with cerebral small vessel disease. J Alzheimers Dis 42(Suppl 3):S37–S43

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Carolis, A., Cipollini, V., Donato, N. et al. Cognitive profiles in degenerative dementia without evidence of small vessel pathology and small vessel vascular dementia. Neurol Sci 38, 101–107 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2716-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2716-5