Abstract

Objective

The aim of this retrospective study is to compare the results of starting rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment with tight control strategy in the window of opportunity and later phases of the disease in real-world clinical practice.

Methods

In this cohort, 609 RA patients were divided into three groups: (i) very early treatment (VET): ≤ 3 months; (ii) early treatment (ET): 3–12 months; and (iii) late treatment (LT) > 12 months after the onset of the disease. Four levels of remission were defined: (i) sustained remission on treatment, (ii) sustained glucocorticoids free remission, (iii) sustained disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) free remission, and (iv) long-term remission. Outcome was assessed based on the number of patients in sustained or long-term remission and patients with poor joint outcome and systemic involvement.

Results

There were no significant differences in the remission rate between the groups. Time to sustained remission in VET group was shorter than ET and LT groups. There were no significant differences in the rate and duration of prednisolone discontinuation in the studied groups. DMARDs were discontinued in VET, ET, and LT groups in 8.7%, 10.2%, and 7% of the patients, respectively. Poor joint outcome occurred in 33.2%, 50.5%, and 59.4% of the patients in the VET, ET, and LT groups, respectively. Remission induction in the first year of the treatment was associated with long-term remission in the VET, ET, and LT groups.

Conclusions

Medications free remission in RA is rare, and although treatment with DMARDs within 3 months of the onset of the disease can prevent joint damage, it cannot lead to long-term remission and discontinuation of medications.

Key Points

• Medications free remission in rheumatoid arthritis is rare.

• Treatment with DMARDs within 3 months of the onset of the disease can prevent joint damage, but it cannot lead to long-term remission and discontinuation of medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Current treatment strategy for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is starting with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) as soon as possible and adjusting the dose of the medications according to the disease activity to achieve remission [1, 2]. According to the concept of window of opportunity, aggressive treatment during the first 3 months after the onset of the first symptoms of RA may lead to a durable remission and increase the quality of life [3,4,5]. It is hoped that induction of remission in the early stages of the disease will decrease the dose and duration of treatment with DMARDs [3,4,5].

The evidence of better results of treating RA in the window of opportunity comes from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). However, the result of RCTs may not work in the daily practice [6,7,8]. The aim of this observational study is to compare the results of starting RA treatment with DMARDs and tight control strategy in the window of opportunity and later phases of the disease in real-world clinical practice.

Methods

Study population

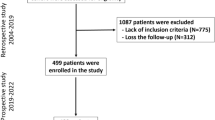

Data for this retrospective study were collected from RA patients from the Connective Tissue Diseases Research Center RA cohort (CTDRC-RA). In this study, patients who were followed from 2004 to 2020 were screened for inclusion in the study. The inclusion criteria were: (i) fulfillment of the ACR/EULAR 2010 criteria for RA at baseline or cumulatively during the first year of follow-up; (ii) age over 16 years at disease onset; (iii) follow-up for at least 12 months; (iv) at least 3 visits per year; (v) DMARDs naïve at the cohort entry; and (vi) active disease at the cohort entry. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1397.452). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Patients were divided into three groups based on the time interval between the onset of the joint symptoms and the start of treatment: (i) very early treatment (VET): ≤ 3 months; (ii) early treatment (ET): 3–12 months; and (iii) late treatment (LT) > 12 months after the onset of the disease.

Data collection, remission assessment, and outcome measures

We collected demographic, clinical, and laboratory data by reviewing the patient charts. Disease activity was assessed by Disease Activity Score-28 for RA with C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) and ACR/EULAR Boolean criteria. Remission according ACR/EULAR Boolean criteria was defined as tender joint count and swollen joint count ≤ 1, patient global assessment ≤ 1 on a visual analog scale 0–10 scale, and CRP ≤ 1 mg/dl. The range of motion of the joints was assessed by an expert rheumatologist. We considered fixed limitation of motion as a measure of irreversible joint damage.

Four levels of remission were defined (Table 1). Remission duration was defined as time between the first visit in remission and the next visit with active disease. In each patient, only the first episode of sustained remission was analyzed. However, for long-term remission, the remission episode with the longest duration was applied.

Outcome was assessed based on the number of patients in sustained remission or long-term remission, and patients with poor joint outcome including joints with limitation of motion or deformity related to RA and systemic involvement.

Treatment

According to the CTDRC protocol, treatment was started with a combination therapy of 2 conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) and prednisolone 7.5–30 mg/day in all the patients. The csDMARDs used were escalating doses of methotrexate up to 25 mg/week and hydroxychloroquine 5 mg/kg/day or sulfasalazine (1500–2000 mg/day). In patients with intolerance or contra-indication to methotrexate, leflunomide 20 mg/day was used. In patients with poor response in 3 months, a third csDMARD was added. In refractory cases, based on the rheumatologist’s decision or patient preference, one of the following methods was used: (i) using biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), (ii) adding the fourth csDMARD that in the majority of the patients it was leflunomide, and (iii) replacing MTX with leflunomide. Treatment with bDMARDs was started with a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi). In refractory cases, another TNFi was used, and in patients with lack of response to TNFis or efficacy loss, rituximab was prescribed. The target of the treatment was remission. Prednisolone was tapered and discontinued in 3–6 months in patients whose symptoms were controlled. Based on the rheumatologist’s decision or patient’s preference, DMARDs in patients with sustained remission for 12 months were tapered and discontinued.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., USA). The normal distribution of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (25–75% interquartile range [IQR]), respectively. Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage. Comparisons between groups were made by chi-squared test, independent sample t test, and U Mann–Whitney test as appropriate. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

From the 1818 screened patients, 609 RA patients were enrolled in the study. The median duration of follow-up was 70 (12, 494) months. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics and medications are shown in Table 2. Except for a higher frequency of metacarpophalangeal joints involvement and rheumatoid factor/anti-cyclic citrullinated peptides positivity in the LT group, and elbow involvement in the ET group compared with VET group, no significant differences were observed between the studied groups at the cohort entry.

We compared the rate of remission in the studied groups (Table 3, Fig. 1). There were no significant differences between them. Time to sustained remission in VET group was shorter than ET and LT groups. However, only the difference between VET and ET groups reaches to significant levels (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the rate and duration of prednisolone discontinuation in the studied groups (Table 3). DMARDs were discontinued in the VET, ET, and LT groups in 8.7%, 10.2%, and 7% of the patients, respectively. However, disease flared in 82.4%, 78.6%, and 71.4% of the patients in the 3 studied groups, respectively (P > 0.05).

We compared poor outcome rate in the studied groups (Table 3). Poor joint outcome in the VET, ET, and LT groups occurred in 33.2%, 50.5%, and 59.4% of the patients, respectively (P = 0.001). Systemic involvement in the VET group was less frequent than the other groups (Table 3). However, difference did not reach to a significant level (Table 3).

In order to assess factors associated with long-term remission (remission longer than 5 years) in the VET, ET, and LT groups, 341 patients with a follow-up of longer than 5 years were included (Table 4). Remission induction in the first year of the treatment was associated with long-term remission in the VET, ET, and LT groups (Table 4). Adherence to therapy was significantly associated with long-term remission only in the LT group (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study shows that starting treatment of RA with a combination of two DMARDs and a tight control strategy at any time after onset of the first symptoms of RA may lead to the same rate of remission. However, diagnosing RA and starting treatment in the window of opportunity may lead to less joint destruction and a lower rate of systemic involvement. Long-term and DMARD-free remission in RA occurs rarely.

Differences between our results and previous studies that showed a higher remission rate in RA patients treated earlier may be related to the differences in the real-world evidence (RWE) and evidence from RCTs [10]. Although RCTs give the highest level of evidence, they describe the outcomes in a homogenous group of patients in a relatively short duration of follow-up (usually 6–24 months). In our study, median duration of follow-up was 70 months. For this reason, RCTs do not necessarily represent the entire spectrum of disease seen in the daily practice [10]. However, it should be noticed that RWE are less controlled and prone to various types of bias [10]. Another explanation for such a difference is that there may not be a real window of opportunity in which RA is susceptible to treatment. The exact timing of the window of opportunity is not defined. Early studies describe it as the first 1–2 years after illness [11]. However, with time, the window of opportunity has been reduced to a shorter period, and in recent years, most studies refer to it as the first 3 months after the onset of RA symptoms where irreversible autoimmunity development could be prevented by treatment with DMARDs [11]. Despite the strong evidences maintaining that starting treatment in the first months after the first symptoms of RA can decrease radiographic damage and functional disability [11], no convincing evidence supports the idea that autoimmunity is reversible in the window of opportunity and early treatment with DMARDs can prevent it. In a study that assessed the 5-year outcomes of the PROMT study, no significant difference was observed in the medication-free remission rate in the patients who received MTX or placebo [12]. In the ADJUST trial, patients with undifferentiated arthritis were randomized to 2 groups of treatment: with abatacept or placebo for 6 months and followed for 2 years [13]. RA developed in 46% and 67% of abatacept and placebo groups, respectively. Six months after stopping the treatment, 48% of abatacept group and 39% of the placebo group were in remission (P > 0.05). This study showed that although progression to RA was lower in the abatacept group compared with the placebo group, abatacept could not prevent RA development in many patients, and there was no significant difference in the remission rate at the end of the study between the 2 groups. By analyzing time-to-outcome curves of BeST and IMPROVED studies for the relationship between the time of treatment initiation and the chance to achieve sustained medications free remission, Bergstra et al. could not find evidence for a window of opportunity during the 2 years after starting RA symptoms [14].

The advantage of our study was analyzing data of a relatively large number of patients followed for a long period of time and treated with a uniform strategy. This study had some important limitations, including (i) lack of information about the articular damage assessed by imaging at the baseline and during the follow-up and (ii) probability of recall bias during collecting information about the start time of RA.

Conclusion

Medication-free remission in RA is rare, and although treatment with DMARDs within 3 months of the onset of the disease can prevent joint damage, it cannot lead to a long-term remission and medication-free disease.

References

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G et al (2010) Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 69:631–637

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M et al (2017) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 76:96077

Quinn MA, Emery P (2003) Window of opportunity in early rheumatoid arthritis: possibility of altering the disease process with early intervention. Clin Exp Rheumatol 21:S154–S157

Boers M (2003) Understanding the window of opportunity concept in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48:1771–1774

Raza K, Saber TP, Kvien TK, Tak PP, Gerlag DM (2012) Timing the therapeutic window of opportunity in early rheumatoid arthritis: proposal for definitions of disease duration in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 71:1921–1923

Sokka T, Hetland ML, Mäkinen H, Kautiainen H, Hørslev-Petersen K, Luukkainen RK et al (2008) Remission and rheumatoid arthritis: data on patients receiving usual care in twenty-four countries. Arthritis Rheum 58:2642–2651

Chandrashekara S, Shobha V, Dharmanand BG, Jois R, Kumar S, Mahendranath KM et al (2018) Factors influencing remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients: results from Karnataka rheumatoid arthritis comorbidity (KRAC) study. Int J Rheum Dis 21:1977–1985

Kievit W, Fransen J, Oerlemans AJ, Kuper HH, van der Laar MA, de Rooij DJ et al (2007) The efficacy of anti-TNF in rheumatoid arthritis, a comparison between randomised controlled trials and clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 66:1473–1478

Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LH, Funovits J et al (2011) American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Provisional Definition of Remission in Rheumatoid Arthritis for Clinical Trials. Ann Rheum Dis 70:40413

Prasanna Misra D, Agarwal V (2019) Real-world evidence in rheumatic diseases: relevance and lessons learnt. Rheumatol Int 39:403–416

Burgers LE, Raza K, Helm-van Mil AH (2019) Window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis – definitions and supporting evidence: from old to new perspectives. RMD Open 5:e000870

van Aken J, Heimans L, Gillet-van Dongen H, Visser K, Ronday HK, Speyer I et al (2014) Five-year outcomes of probable rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate or placebo during the first year (the PROMPT study). Ann Rheum Dis 73:396–400

Emery P, Durez P, Dougados M, Legerton CW, Becker JC, Vratsanos G et al (2010) Impact of T-cell costimulation modulation in patients with undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis or very early rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and imaging study of abatacept (the ADJUST trial). Ann Rheum Dis 69:510–516

Bergstra SA, Van Der Pol JA, Riyazi N, Goekoop-Ruiterman YPM, Kerstens PJSM, Lems W et al (2020) Earlier is better when treating rheumatoid arthritis: but can we detect a window of opportunity? RMD Open 6:e001242

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients for participating in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS, AKH, and AMM designed the study; SE, AS, KE, AKH, and MH were involved in the data acquisition and/or management; AKH and AMM analyzed the data and critically interpreted the results; SE, AMM, and AKH were involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ebrahimian, S., Salami, A., Malek Mahdavi, A. et al. Can treating rheumatoid arthritis with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs at the window of opportunity with tight control strategy lead to long-term remission and medications free remission in real-world clinical practice? A cohort study . Clin Rheumatol 40, 4485–4491 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-021-05831-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-021-05831-3