Abstract

Objectives

This study was conducted to analyze clinical characteristics, laboratory data, disease activity, and outcome of juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus (jSLE) patients from southern Turkey.

Methods

Fifty-three patients with jSLE diagnosed according to the revised American College of Rheumatology 1997 criteria between January 2005 and June 2018 were included in the present study.

Results

The median age at the diagnosis was 12.8 (range, 5.1–17.7) years. The female to male ratio was 9.6:1. The most prevalent clinical features were mucocutaneous involvement (96.2%) and constitutional manifestations (94.3%). Renal manifestations, hematological manifestations, and neuropsychiatric involvement were detected in 40 (75%), in 38 (71.7%), and in 13 (24.5%) patients, respectively. Renal biopsy was performed to 49 patients (92.5%). Class IV lupus nephritis (LN) (34%) and class II LN (20.4%) were the most common findings. Mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide with corticosteroid were the main treatment options. Eighteen patients received rituximab and one tocilizumab. The mean SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score at the time of diagnosis was 22.47 ± 8.8 (range = 3–49), and 1.34 ± 1.85 (range = 0–7) at last visit. Twenty-one patients (39.6%) had damage in agreement with Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (PedSDI; mean = 0.60 ± 0.94; range = 0–5) criteria. Growth failure was the most prevalent cause of damage (n = 13, 26%). One patient deceased due to severe pulmonary hemorrhage and multiple cerebral thromboses.

Conclusion

jSLE patients in this cohort have severe disease in view of the higher frequency of renal and neurologic involvement. Nevertheless, multicenter studies are needed to make a conclusion for all Turkish children with jSLE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic autoimmune disease characterized by various clinical and immunological features. Approximately 15–20% of SLE patients have a disease onset before the age of 16 which named juvenile SLE (jSLE). Incidence, severity, system involvement, and outcome of disease differ among ethnic groups [1]. Even the populations from the same ethnic group living around different parts of the world show distinct disease courses which are suggesting the effect of geographic and environmental factors besides genetic susceptibility [2]. Juvenile SLE is among rare diseases with an incidence of 0.3–0.9 per 100,000 children-years and a prevalence of 1.89–25.7 per 100,000 children [3,4,5].

jSLE and adult-onset SLE (aSLE) are clinically and serologically different. Disease severity and outcome are more severe in childhood due to the frequency of central nervous system and kidney involvement [6, 7]. Therefore, there are researches going on to determine novel biomarkers which will assist the early diagnosis of organ involvement [8, 9]. Clinical features, laboratory data, diagnostic criteria, and treatment options of jSLE are based on adult data owing to its rarity and paucity of research. Therefore, management of disease differs among countries and even centers and clinicians. To avoid this and make collaboration between countries, SHARE (Single Hub and Access point for pediatric Rheumatology in Europe) initiative has published evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis [10, 11]. Nevertheless, evidence regarding diagnosis and treatment in jSLE are insufficient. Therefore, the unmet need for more research on the diagnostic approach and treatment options are still alive.

Given the rarity of the disease, lack of research from Turkey is not really surprising. To date, there is only one report regarding demographic, clinical, and laboratory features and outcome of jSLE from Turkey. Hence, this study was conducted to analyze clinical characteristics, laborator, and immunological data, disease activity, and outcome of jSLE patients from a referral center in southern Turkey.

Material and methods

Participants

Fifty-three patients, who were younger than 18 years old at the time of diagnosis, diagnosed between January 2005 and June 2018 were included in this retrospective longitudinal study. The patients had met the revised 1997 criteria of American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria of SLE [12]. All patients were regularly followed up by the same pediatric rheumatologist as well as pediatric nephrologist according to clinical characteristics and disease activity, at least at 2 months interval. Routine clinical care was continued until the patients transferred to adult rheumatology department or moved to another city for living. Prior to the initiation of the study, approval of the institutional review board of the local medical school was obtained.

Clinical and laboratory data

Clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters included this study were collected retrospectively from medical files. Neuropsychiatric involvement was determined with respect to 1999 ACR neuropsychiatric lupus criteria [13]. Renal biopsy was performed routinely for those whose parents accepted the procedure irrespective of renal condition. The International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) 2003 classification criteria were used to classify the biopsy findings [14]. Cardiac involvement was assessed by routinely performed echocardiography at the time of diagnosis. Additionally, constitutional symptoms (fever, fatigue, weight loss, loss of appetite); mucocutaneous features (discoid lesions, malar rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, alopecia); musculoskeletal symptoms (arthritis, myositis); hypertension; pulmonary symptoms (effusion, shrinking lung, hemorrhage); pulmonary hypertension; and cardiac symptoms (pericardial effusion) were collected.

Whole blood count (WBC); C-reactive protein (CRP); erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); complement levels (C3, C4); autoantibodies including antinuclear antibodies (ANA); anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), and anticardiolipin (aCL) were analyzed at the time of diagnosis. ANA and anti-dsDNA levels were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). However, serological tests for other autoantibodies were not routinely performed for all patients; therefore, they are not presented.

Disease activity and outcome

The SLE Disease Activity Index-2000 (SLEDAI-2K) was performed at the time of diagnosis and every visit to assess disease activity [15]. The score of some patients, who were diagnosed before the establishing SLEDAI-2K score, were calculated from medical data.

The disease outcome was measured at last clinical visit based on the pediatric version of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (PedSDI) [16].

All patients’ information were available for the data collection but three of them have been followed less than 6 months; therefore, analyses of last-visit SLEDAI-2K scores, pedSDI, and medical data were done for 50 patients. However, demographic and clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and the SLEDAI-2K scores at the time of diagnosis were analyzed for all 53 patients.

Statistics

All statistical analyzes were conducted using SPSS software version 20.0. Patient characteristics and treatment information were analyzed descriptively. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, whereas continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation and as median and minimum-maximum where appropriate.

Results

Demographic characteristics

All patients diagnosed with jSLE were of Turkish ancestry. The female to male ratio was 9.6:1 with a strong predominance of the female. While the median age at symptoms onset was 12.2 (range, 5.09–17.3) years, the median age at the time of diagnosis of jSLE was 12.8 (range, 5.1–17.7) years. The median interval between disease onset and diagnosis was 2 (range, 0–36) months. The median duration of the disease was 3.12 (range, 0.10–9.96) years. Parental consanguinity discovered in 14 (26.4%) patients. The families were questioned in terms of the presence of autoimmune disease in themselves and in first-degree relatives. History of SLE was present in six (11.3%), hypothyroidism in five (9.4%), juvenile idiopathic arthritis/rheumatoid arthritis (JIA/RA) in five (7.5%), Behçet’s disease in 2 (3.8%) patients, and scleroderma in only one (1.9%) patient. Moreover, two of the jSLE patients were sisters.

Clinical characteristics

The mucocutaneous involvement was the most prevalent clinical feature with a frequency of 96.2%, followed by constitutional manifestations (94.3%). Cumulative frequencies of systemic involvement of the 53 patients were given in Table 1.

One of the other frequent features were renal manifestations. Renal involvement was detected in 40 (75%) patients; nevertheless, nephrotic range proteinuria was seen in 15 (28.3%) of them. Renal biopsy was performed to 49 patients, of which 18 (34%) had class IV, and 10 (20.4%) had class II lupus nephritis (LN) (Table 2). Interestingly, half of the class IV LN patients did not have nephrotic range proteinuria at the time of renal biopsy but hematuria or nephritic range proteinuria. Despite the large amount of renal involvement, hypertension was found in only seven (13.2%) patients.

Hematological manifestations were detected in 38 (71.7%) patients. While lymphopenia (64.2%) was the leading hematological symptom followed by leukopenia (49.1%) and hemolytic anemia (43.4%), thrombocytopenia was the least seen manifestation with a frequency of 32.1%.

Neuropsychiatric involvement developed in 13 (24.5%) patients. Severe headache (n = 11) was the most prevalent symptom followed by seizure (n = 5), psychosis (n = 1), cognitive dysfunction (n = 1), and anxiety disorder (n = 1).

While serositis (pleurisy, ascites) was found in eight (15%) patients, and cardiac involvement (valvular disease, pericarditis or pericardial effusion) was detected in five (9.4%) patients. Only one patient presented with pulmonary hemorrhage.

Laboratory data

ANA and anti-dsDNA positivity were not detected in all patients but in 46 (86.8%) and in 24 (45.3%) patients, respectively. Hypocomplementemia was detected in 50 patients (94.3%): low C3 in 42 (79.2%) and low C4 in 49 (92.5%).

The only tested antiphospholipid antibodies in all patients were aCL IgG and IgM. Anti-CL IgG and IgM positivity were seen in 8 (15.1%) and in 11 patients (20.8%), respectively. At the follow-up period, two patients developed thrombosis: two cerebral and one left leg deep venous thrombosis. Only one patient with cerebral thrombosis had transiently positive aCL IgM.

The median leukocyte, lymphocyte, and platelet count were 4600 c/mm3 (range 760–14,200), 1300 c/mm3 (range 310–4200), and 223.000 c/mm3 (range 20.000–496,000), respectively. While the median ESR was 30 mm/h (range 2–140), the median CRP was 0.3 mg/dl (range 0.1–25.9). All laboratory data are presented in Table 3.

Medication data

Literally, all patients received oral corticosteroid treatment (n = 50, 100%) and most of it combined with hydroxychloroquine (n = 47, 94%). The frequency of pulse corticosteroid was 42% (n = 21). As a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), mycophenolate mofetil was the most frequently used agent (n = 41, 82%) followed by cyclophosphamide (n = 33, 66%). Azathioprine (n = 5, 10%) and methotrexate (n = 4, 8%) were not the first choices of treatments.

Principally, patients with class I or II LN who had no other severe organ involvement were treated with corticosteroid and mycophenolate mofetil. Nevertheless, patients with either class III or IV LN were treated with six doses monthly cyclophosphamide infusions thereafter mycophenolate mofetil. However, 24 patients with class III/IV LN were not shown an adequate renal response to cyclophosphamide treatment; therefore, rituximab infusions were administered. Eighteen (36%) of the 50 jSLE patients received rituximab owing to refractory nephritis (n = 15), resistant pancytopenia (n = 1), and severe neuropsychiatric involvement (n = 2).

Initially, none of the patients presented with massive pericardial effusion. Nevertheless, one patient, who had class IV LN and had been treated with monthly cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and thereafter, with rituximab, developed massive intractable pericardial and bilateral pleural effusion and still had nephrotic range proteinuria. Bilateral chest tubes were placed and pericardiocentesis was performed. Nevertheless, the accumulation of the fluid was very enormous, which caused cardiac tamponade. Therefore, pericardial excision to drain the fluid to the pleural space was mandatory. Although pericardial fenestration was effective to control the massive effusion in the pericardium for a while, the fluid was re-accumulated. Owing to the severity and unresponsiveness to the pericardial fenestration, pericardiectomy was performed surgically. Meanwhile, the patient was treated with three doses of intravenous pulse methylprednisolone and continued orally with a dose of equally to 2 mg/kg/day prednisolone. Mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine were continued as well. The other possible cause of effusion such as tuberculosis, infections, and malignancies were excluded. Since the patient was unresponsive to the therapies and pericardial/pleural effusion was related to the jSLE, rituximab treatment was repeated but she developed an anaphylactic reaction to the drug. Hence, rituximab was given with desensitization technique; however, it was not successful. Owing to the unresponsiveness to the conventional treatment, intravenous tocilizumab was started at a dose of 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Pericardial and bilateral pleural effusions were gradually decreased, and finally, there were no effusions which were confirmed by echocardiography and chest computed tomography. Even, the dose of methylprednisolone was gradually tapered. Although pathological renal findings and complement levels were not improved completely, renal function tests, proteinuria, and complement levels did not deteriorate further during the 1 year follow-up treatment with tocilizumab, mycophenolate mofetil, and oral methylprednisolone (16 mg/day).

At the time of diagnosis, seven (14%) patients were treated with plasmapheresis due to severe pancytopenia (n = 2), severe acute renal insufficiency and massive ascites (n = 2), macrophage activation syndrome (n = 1), and neuropsychiatric involvement (n = 2).

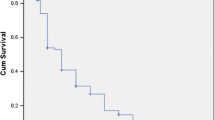

Disease activity, damage, and outcome

The mean SLEDAI score at the time of diagnosis was 22.47 ± 8.8 (range 3–49), and it decreased to 1.34 ± 1.85 (range 0–7) at last visit. Nevertheless, 21 of 50 patients (%39.6) had damage in agreement with PedSDI criteria. The mean PedSDI score of the patients was 0.60 ± 0.94 (range 0–5). PedSDI scores were analyzed individually for all patients and found out that growth failure was the most prevalent cause of damage (n = 13, 26%). Furthermore, cataract was detected in four patients (8%), venous thrombosis in three (6%), and nephrotic proteinuria in three (6%). Individually, one patient had skin scars on the face and one muscle atrophy. Additionally, one patient suffered from pericardiectomy, shrinking lung, pubertal delay, growth failure, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) without dialysis requirement (Table 4). In this cohort, one patient, who manifested with pulmonary hemorrhage and had class 1 LN, treated with pulse methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide deceased due to multiple cerebral thrombosis and massive pulmonary hemorrhage. She was tested for antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and possible cause of thrombosis. The tests were all normal, including antiphospholipid antibody IgG and IgM, aCL IgG and IgM, anti-Beta-2-Glycoprotein I antibody IgG and IgM and lupus anticoagulant, protein-S, and antithrombin-3.

Discussion

In the present cohort, we have described demographic features, clinical and laboratory characteristics, disease activity, and outcome of jSLE patients, diagnosed and followed over the past 13 years by the same pediatric rheumatologist in southern Turkey. Besides, we confronted our jSLE patients’ characteristics with the local data and the data from other countries as well.

Juvenile SLE comprises 15–20% of all SLE patients which have disease onset in childhood. The organ involvement, severity, and outcome of disease are more concerning in childhood-onset SLE [6, 7]. Both childhood and adult-onset SLE have a high preponderance in females from 86% to 92% and 75% to 91%, respectively [7, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. We have seen the similar frequency of the female proportion in the present study, which was 90.6%, compared to the previous studies [17,18,19,20,21]. However, a cohort of 92 jSLE patients was published recently, which represents the first and only detailed assessment of jSLE patients in Turkey so far. The researchers discovered that the female proportion was 77.2%, which is much lesser than our data [8]. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that the studies have been carried out in hospitals from different parts of Turkey.

There were no differences than the other studies in terms of the mean age at the disease onset and the diagnosis [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Besides, the median duration between disease onset and diagnosis was 2 months, similar to the study of Sahin et al. [8]. Hence, we can say that there was not a diagnostic delay in our experience.

The most prevalent clinical characteristics we experienced in this cohort were mucocutaneous manifestations and constitutional symptoms followed by renal, hematological, and musculoskeletal symptoms similar to the previous studies [20, 26, 27].

As we know from previous studies, the frequency of renal and neuropsychiatric involvement, which are mostly the cause of mortality and morbidity in jSLE patients, are much prevalent in Asian and African-American patients [1, 28]. Despite that knowledge, in the present study, renal and neuropsychiatric involvement discovered in 40 (75.4%) and in 13 (24.5%) patients, respectively, which were greater than the previous study conducted in Turkey [8]. To classify renal involvement, 92.5% (n = 49) of the jSLE patients underwent renal biopsy and biopsy-proven lupus nephritis was identified in 40 (75.4%) patients. In the present study, LN classes IV and II were the most encountered features in renal biopsy, in 18 (34%) and in 10 (20.4%) patients, respectively. Similar to our study, in previous studies, class IV LN was the most common histological feature identified on renal biopsy [21, 29,30,31].

The frequency of neuropsychiatric involvement reported in jSLE patients ranges between 7.7 and 45% [21, 27, 30,31,32]. This great fluctuation is likely due to the inclusion criteria, ethnic differences, and environmental factors that influence the disease manifestations. However, in an Egypt cohort, the frequency of neuropsychiatric involvement was reported in 46.3% of jSLE patients. The prospective nature of this study allowed them to evaluate cognitive disorders thoroughly by psychiatric consultations for objective cognitive dysfunction evaluation by standardized neuropsychological tests [24]. Therefore, considering cognitive disorders as neurologic involvement may explain the high frequency. The neuropsychiatric involvement in jSLE in the previous study reported from Turkey was slightly lesser than our present report, 16.3% and 24.5%, respectively which were alike to the other studies [8, 30,31,32]. Nevertheless, this study was planned and evaluated retrospectively; therefore, psychiatric consultations for objective cognitive dysfunction evaluation by standardized neuropsychological tests were not a reachable goal.

Serositis and cardiac involvement were detected in 8 (15%) and in 5 (9.4%) patients, respectively. The percentages of these involvements in the former study from Turkey were 12% and 2.2%, respectively. Cardiac involvement of the present study was slightly higher than the former. Nevertheless, the results of the present study were comparable to the previous studies [20, 21, 24]. It is important to mention that the patient who developed massive pericardial and pleural effusion have been successfully treated with off-label use of tocilizumab, although renal findings were not improved.

Although none of the patients presented with massive pericardial effusion, one patient later developed massive intractable pericardial effusion which required pericardiocentesis, pericardial fenestration, and subsequently, pericardiectomy. The pericardial and pleural effusion were gradually resolved with off-label use of tocilizumab. However, in renal findings, complement levels have remained stable. IL-6 promptly and transiently produced in response to infections and tissue injuries and is a multifunctional cytokine that plays numerous roles in host defense. Although its expression is controlled by transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms, dysregulated continuous synthesis of IL-6 plays a pathological role on chronic inflammation and autoimmunity. Tocilizumab, a humanized anti-IL-6 receptor antibody which binds to soluble IL-6 receptors leads to inhibition of receptor-mediated IL-6 signaling and suppression of physiological activities of IL-6 [33]. In lupus patients, B cells secrete large amounts of IL-6 and continuously express IL-6 receptors that lead to cell hyperactivity, which mediates organ damage. Besides, some studies have been demonstrated that IL-6 correlates with disease activity and might even be a useful biomarker of SLE [34]. Moreover, tocilizumab has been used in adult patients with massive/recurrent pericardial and pleural effusion, which were unresponsive to conventional therapies and pericardial fenestration (in one) in two different reports [35, 36]. Although it has been reported in adult patients, there are no previous reports on tocilizumab for the treatment of pericardial effusion in patients with jSLE. Therefore, this study reports the first patient with jSLE who had massive intractable pericardial and pleural effusion successfully treated with tocilizumab.

Arthritis is one of the most encountered manifestations of SLE in both children and adults and is one of the diagnostic criteria of SLE, in fact. Unlike the arthritis seen in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, the arthritis of SLE is typically non-erosive and non-deforming [12]. The frequency of acute arthritis in the previous studies ranges from 14.5 to 67% [8, 21, 22, 25,26,27]. Chronic arthritis, defined as persistence of arthritis for more than 6 weeks, is rare in childhood SLE with a prevalence of 2.6% [37]. Although the arthritis of SLE does not generally cause joint damage, it can be associated with significant decrease in quality of life in these children [38]. Similar to the other studies, the frequency of acute arthritis in the present study was 66% (n = 35). Nevertheless, chronic arthritis was not encountered in this cohort.

As we know from family and twin studies, genetic susceptibility plays a role in the etiology of SLE. First-degree relatives of SLE patients have a 20-fold increased risk for SLE compared to the general population [39]. Twin concordance rates for SLE is much higher in monogenic twins than dizygotic, 24% and 2%, respectively [40]. In general terms, familial cases of SLE represent about 10% of cases [41]. In the present cohort, the percentage of family consanguinity was 24.6% (n = 14) and the percentage of SLE in first-degree relatives was 11.3% (n = 6), in which two of them were sisters. A history of autoimmune diseases in the first-degree relatives was positive for rheumatoid arthritis in 4, Behçet’s disease in 2 patients, and systemic scleroderma in one patient. The frequencies of ANA and anti-dsDNA positivity, hypocomplementemia, were similar to the previous studies [8, 21, 25].

Although the mortality of jSLE is mostly due to renal involvement that was not set in our study. Nevertheless, we reported a deceased patient in this cohort, which was due to severe pulmonary hemorrhage and multiple cerebral thromboses. Somehow, the cause of thrombosis and pulmonary hemorrhage was not found despite comprehensive evaluation. Alveolar hemorrhage is a rarely encountered and life-threatening pulmonary manifestation of jSLE which was reported in 4.9% of jSLE patients in a study. Nevertheless, due to its rarity and high risk of mortality, the diagnosis of SLE should be kept in mind in patients who presented with pulmonary hemorrhage [42]. Although the exact mechanism of hemorrhage in SLE is not well known, it seems to involve immune-mediated disruption of small blood vessels with granular immune deposits and complement, uremia, pulmonary infection, and coagulopathies [43].

Similar to the previous studies, mean basal disease activity score, which measured with SLEDAI-2K, was 22.47 ± 8.8 [24, 27, 32, 44]. Additionally, in the present cohort, 21 (39.6%) patients developed damage with mean a pedSDI score of 0.60 ± 0.94. The most encountered damage was growth failure (n = 13, 26%). However, Sahin et al. have found less severe disease activity (10.5 ± 4.8) and only 26.1% of patients developed damage with a mean pedSDI score of 0.45 ± 1 [8]. The more severe basal disease activity in the present study may explain the amount of damage happened to the patients.

Overall, because incidence, severity, system involvement, and outcome of SLE differ among ethnic groups, we compared our findings to those from different geographical parts of the world which are given in Table 5, elaborately [8, 20, 21, 24, 27, 45]. Findings of the present study were more similar to the studies involving Arabs and Asians in terms of high percent of organ involvement, high SLEDAI, and damage score. Cukurova University Hospital is located at southmost of Turkey and on the ancient Silk Road, which connected the East and West, and providing tertiary healthcare to a diverse multicultural pediatric population including Turks, Arabs, Armenian, and hosted emigrants from different nations. This mixed cultural structure of our patients might explain the similarities.

Consequently, studies of jSLE patients from Turkey are scarce. In fact, this study represents the second cohort of jSLE from Turkey. The first cohort was published at the beginning of 2018 by Sahin et al. Both cohorts represent Turkish children, although, findings were distinct in some ways. In this cohort, the presence of neuropsychiatric disease and renal involvement were much higher. Moreover, we have found more severe disease activity and more damaged patients which might be owing to the higher rate of neuropsychiatric and renal involvement. Class IV LN was the most prevalent renal finding in this cohort. However, because they did not perform renal biopsy to all patients who had renal symptoms, we could not compare the findings of biopsy-proven LN. Mycophenolate mofetil was the most frequently used DMARD in this cohort as opposed to the previous study, in which azathioprine was the most prevalent agent. Additionally, 18 (36%) of the 50 jSLE patients received rituximab in view of refractory nephritis, resistant pancytopenia, and severe neuropsychiatric involvement. Nevertheless, the usage of rituximab was 7.6% in the previous study. Moreover, this study reports the first patient with jSLE who had massive intractable pericardial and pleural effusion successfully treated with tocilizumab. The only mortality in this cohort was due to massive pulmonary hemorrhage and multiple cerebral thromboses as opposed to the previous report, in which the cause of mortality was renal involvement. These differences between the two reports of Turkey might explain by geographic and environmental factors, additionally to genetic susceptibility.

There were few limitation points of this cohort. The major limitation was retrospective design and the small number of patients. However, this might be due to the rarity of SLE in childhood and socioeconomic status, thus, lack of accessibility to medical services. Although we evaluated pedSDI scores of the patients, we did not routinely assess the patients for pubertal development. However, we believe that pubertal development is a very important point in patients with chronic diseases and deserve more careful attention.

Since this is the second representative cohort of jSLE patients from Turkey and the first one representing renal biopsy findings of Turkish children, we considered to share this descriptive study. Besides, we have described a patient with massive pericardial and pleural effusion who treated successfully with tocilizumab for the first time in jSLE.

In conclusion, SLE is a multisystemic autoimmune disease leading to distinct clinical features and outcomes even in different regions of the same country. Because this cohort showed more severe disease with neuropsychiatric and renal involvement as opposed to the previous report from Turkey and there was only one report to compare to, prospective, multicenter, and nationwide studies are needed to clarify the overall clinical characteristics and outcome of jSLE in Turkish children.

References

Hiraki LT, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Harvey E, Hebert D, Silverman ED (2009) Ethnic differences in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 36:2539–2546. http://www.jrheum.org/content/36/11/2539

Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS (2006) Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus 15:308–318. https://doi.org/10.1191/0961203306lu2305xx

Pineles D, Valente A, Warren B, Peterson MG, Lehman TJ, Moorthy LN (2011) Worldwide incidence and prevalence of pediatric onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 20:1187–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203311412096

Hiraki LT, Feldman CH, Liu J, Alarcón GS, Fischer MA, Winkelmayer WC, Costenbader KH (2012) Prevalence, incidence, and demographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis from 2000 to 2004 among children in the US Medicaid beneficiary population. Arthritis Rheum 64:2669–2676. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34472

Kamphuis S, Silverman ED (2010) Prevalence and burden of pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6:538–546. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2010.121

Borchers AT, Naguwa SM, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME (2010) The geoepidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev 9:A277–A287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.008

Artim-Esen B, Şahin S, Çene E, Şahinkaya Y, Barut K, Adrovic A, Özlük Y, Kılıçaslan I, Omma A, Gül A, Öcal L, Kasapçopur Ö, İnanç M (2017) Comparison of disease characteristics, organ damage, and survival in patients with juvenile-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a combined cohort from 2 tertiary centers in Turkey. J Rheumatol 44:619–625. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160340

Sahin S, Adrovic A, Barut K, Canpolat N, Ozluk Y, Kilicaslan I, Caliskan S, Sever L, Kasapcopur O (2018) Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus in Turkey: demographic, clinical and laboratory features with disease activity and outcome. Lupus 27:514–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203317747717

Pejchinovski M, Siwy J, Mullen W, Mischak H, Petri MA, Burkly LC, Wei R (2018) Urine peptidomic biomarkers for diagnosis of patients with systematic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 27:6–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203317707827

Groot N, de Graeff N, Avcin T, Bader-Meunier B, Brogan P, Dolezalova P, Feldman B, Kone-Paut I, Lahdenne P, Marks SD, McCann L, Ozen S, Pilkington C, Ravelli A, Royen-Kerkhof AV, Uziel Y, Vastert B, Wulffraat N, Kamphuis S, Beresford MW (2017) European evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 76:1788–1796. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210960

Groot N, de Graeff N, Marks SD, Brogan P, Avcin T, Bader-Meunier B, Dolezalova P, Feldman BM, Kone-Paut I, Lahdenne P, McCann L, Özen S, Pilkington CA, Ravelli A, Royen-Kerkhof AV, Uziel Y, Vastert BJ, Wulffraat NM, Beresford MW, Kamphuis S (2017) European evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of childhood-onset lupus nephritis: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 0:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211898

Hochberg MC (1997) Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40:1725. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(199709)40:9<1725::AID-ART29>3.0.CO;2-Y

The American College of Rheumatology. Nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42: 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<599::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-F.

Weening JJ, D'Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, Balow JE, Bruijn JA, Cook T, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Ginzler EM, Hebert L, Hill G, Hill P, Jennette JC, Kong NC, Lesavre P, Lockshin M, Looi LM, Makino H, Moura LA, Nagata M (2004) The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol 15:241–250. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASN.0000108969.21691.5D

Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB (2002) Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol 29:288–291

Gutiérrez-Suárez R, Ruperto N, Gastaldi R, Pistorio A, Felici E, Burgos-Vargas R, Martini A, Ravelli A (2006) A proposal for a pediatric version of the systemic lupus international collaborating clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index based on the analysis of 1,015 patients with juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 54:2989–2996. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22048

Ambrose N, Morgan TA, Galloway J, Ionnoau Y, Beresford MW, Isenberg DA, UK JSLE Study Group (2016) Differences in disease phenotype and severity in SLE across age groups. Lupus 25:1542–1550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203316644333

Hoffman IE, Lauwerys BR, De Keyser F, Huizinga TW, Isenberg D, Cebecauer L, Dehoorne J, Joos R, Hendrickx G, Houssiau F, Elewaut D (2009) Juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: different clinical and serological pattern than adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 68:412–415. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2008.094813

Borba EF, Araujo DB, Bonfa´ E, Shinjo SK (2013) Clinical and immunological features of 888 Brazilian systemic lupus patients from a monocentric cohort: comparison with other populations. Lupus 22:744–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203313490432

Gulay CB, Dans LF (2011) Clinical presentations and outcomes of Filipino juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 9:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-9-7

Hiraki LT, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Hebert D, Harvey E, Silverman ED (2008) Clinical and laboratory characteristics and long term outcome of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a longitudinal study. J Pediatr 152:550–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.019

Bader-Meunier B, Armengaud JB, Haddad E, Salomon R, Deschênes G, Koné-Paut I, Leblanc T, Loirat C, Niaudet P, Piette JC, Prieur AM, Quartier P, Bouissou F, Foulard M, Leverger G, Lemelle I, Pilet P, Rodière M, Sirvent N, Cochat P (2005) Initial presentation of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a French multicenter study. J Pediatr 146:648–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.045

Adelowo OO, Olaosebikan BH, Animashaun BA, Akintayo RO (2017) Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus in Nigeria. Lupus 26:329–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203316672927

Abdel-Hafez MA, Abdel-Nabi H (2015) Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: onset patterns and short-term outcome in Egyptian children, a single-center experience. Lupus 24:1455–1461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203315598016

Concannon A, Rudge S, Yan J, Reed P (2013) The incidence, diagnostic clinical manifestations and severity of juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus in New Zealand Maori and Pacific Island children: the starship experience (2000–2010). Lupus 22:1156–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203313503051

Abdel-Nabi HH, Abdel-Noor RA (2018) Comparison between disease onset patterns of Egyptian juvenile and adult systemic lupus erythematosus (single Centre experience). Lupus 27:1039–1044. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203318760208

Dung NT, Loan HT, Nielsen S, Zak M, Petersen FK (2012) Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus onset patterns in Vietnamese children: a descriptive study of 45 children. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 10:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-10-38

Couture J, Silverman ED (2016) Update on the pathogenesis and treatment of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol 28:488–496. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000317

Pluchinotta FR, Schiavo B, Vittadello F, Martini G, Perilongo G, Zulian F (2007) Distinctive clinical features of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus in three different age classes. Lupus 16:550–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203307080636

Pattaragarn A, Sumboonnanonda A, Parichatikanond P, Supavekin S, Suntornpoch V, Vongjirad A (2005) Systemic lupus erythematosus in Thai children: clinicopathologic findings and outcome in 82 patients. J Med Assoc Thail 8:232–241

Ramírez Gómez LA, Uribe Uribe O, Osio Uribe O et al (2008) Childhood systemic lupus erythematosus in Latin America. The GLADEL experience in 230 children. Lupus 1:596–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203307088006

Lewandowski LB, Schanberg LE, Thielman N, Phuti A, Kalla AA, Okpechi I, Nourse P, Gajjar P, Faller G, Ambaram P, Reuter H, Spittal G, Scott C (2017) Severe disease presentation and poor outcomes among pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus patients in South Africa. Lupus 26:186–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203316660625

Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T (2014) IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4 6:a016295. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a016295

Tackey E, Lipsky PE, Illei GG (2004) Rationale for interleukin-6 blockade in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 13:339–343. https://doi.org/10.1191/0961203304lu1023oa

Kamata Y, Minota S (2012) Successful treatment of massive intractable pericardial effusion in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus with tocilizumab. BMJ Case Rep 21:2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-007834

Ocampo V, Haaland D, Legault K, Mittoo S, Aitken E (2016) Successful treatment of recurrent pleural and pericardial effusions with tocilizumab in a patient with systemic lupus erythematous. BMJ Case Rep 8:2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-215423

Cavalcante EG, Aikawa NE, Lozano RG, Lotito AP, Jesus AA, Silva CA (2011) Chronic polyarthritis as the first manifestation of juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus 20:960–964. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203311400113

Brunner HI, Higgins GC, Wiers K, Lapidus SK, Olson JC, Onel K, Punaro M, Ying J, Klein-Gitelman MS, Seid M (2009) Health-related quality of life and its relationship to patient disease course in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 36:1536–1545. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.081164

Alarcón-Segovia D, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Cardiel MH, Caeiro F, Massardo L, Villa AR, Pons-Estel BA, on behalf of the Grupo Latinoamericano de Estudio del Lupus Eritematoso (GLADEL) (2005) Familial aggregation of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune diseases in 1,177 lupus patients from the GLADEL cohort. Arthritis Rheum 52:1138–1147. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20999

Deapen D, Escalante A, Weinrib L, Horwitz D, Bachman B, Roy-Burman P, Walker A, Mack TM (1992) A revised estimate of twin concordance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 35:311–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780350310

Al Arfaj AS, Khalil N (2009) Clinical and immunological manifestations in 624 SLE patients in Saudi Arabia. Lupus 18:465–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203308100660

Araujo DB, Borba EF, Silva CA, Campos LM, Pereira RM, Bonfa E, Shinjo SK (2012) Alveolar hemorrhage: distinct features of juvenile and adult onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 21:872–877. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203312441047

Martinez-Martinez MU, Abud-Mendoza C (2014) Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical manifestations, treatment, and prognosis. Reumatol Clin 10:248–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2014.02.002

Tan JH, Hoh SF, Win MT, Chan YH, Das L, Arkachaisri T (2015) Childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Singapore: clinical phenotypes, disease activity, damage, and autoantibody profiles. Lupus 24:998–1005. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203315584413

Al-Mayouf SM (2013) Systemic lupus erythematosus in Saudi children: long-term outcomes. Int J Rheum Dis 16:56–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.12020

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Balci and Dr. Yilmaz conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Kişla Ekinci, Dr.Karabay Bayazit, Dr. Melek, and Dr. Dogruel collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Altintas and Dr. Dogruel designed the data collection instruments, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval of the institutional review board of the local medical school was obtained.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians according to legal ethics regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balci, S., Ekinci, R.M.K., Bayazit, A.K. et al. Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: a single-center experience from southern Turkey. Clin Rheumatol 38, 1459–1468 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04433-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04433-4