Abstract

Obesity in rheumatoid arthritis has been associated with increased risk of comorbidities, larger medical costs, decreased quality of life, higher disease activity, and reduced therapeutic responses. We assessed the burden of obesity among rheumatoid arthritis patients and its impact on patient-reported outcomes. Patients receiving care at two Canadian University Centers were included. Height and weight were measured and selected sociodemographic and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) characteristics as well as patient-reported outcomes were obtained. Patients were classified according to WHO criteria and proposed RA cut points, and results were compared with national data. Using WHO criteria, 68 (34 %) RA patients were classified as obese (vs. ~25 % of Canadians). Using RA cut points, 112 (55 %) RA patients were classified as obese. With both classification methods, obese individuals had significantly higher mean HAQ scores and a higher odds of significant disability (HAQ ≥ 1: WHO OR 2.3; 95 % CI 1.2, 4.2 and RA-specific OR 1.8; 95 % CI 1.0, 3.2). Independent of the classification method use, RA patients have significantly higher rates of obesity than national prevalence estimates. Obese RA patients had about twice the odds of reporting moderate to severe disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients have a reduced life expectancy compared with the general population, mainly due to an increased prevalence of, and worse outcomes from, cardiovascular (CV) disease (CVD) [1]. Genetic predisposition, traditional CV risk (CVR) factors, and the effects of systemic inflammation on the vasculature contribute to the excess CV morbidity and mortality in RA [2, 3]. Among traditional CVR factors, obesity is associated with increased risk of comorbidities, the need for total joint replacement, increased medical costs, and decreased quality of life [4]. Excess weight is also associated with higher RA disease activity and reduced therapeutic benefits of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs [5].

Body mass index (BMI) provides a relative estimate of body fatness, and excess fat is a potent predictor of CVD and overall mortality [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines overweight as BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 and obesity as BMI ≥30 kg/m2 [7]. In RA, WHO cut points appear to underestimate body fat, and lower sex-specific thresholds to define overweight and obesity based on DEXA-derived estimates of fatness have been proposed [8, 9]. The goal of this study was to estimate the burden of obesity in RA patients using both classification systems.

Materials and methods

Consecutive RA patients ≥18 years of age treated at arthritis clinics of McGill University (n = 94) and the University of Manitoba (n = 106) between 2012 and 2013 were included. All met the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for RA. This study was approved by the ethics committees at each center.

Demographics, smoking status, and RA characteristics (disease duration, RF and anti-CCP antibodies, ESR, CRP, tender and swollen joint counts) were abstracted from medical records. BMI and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were obtained at the time of evaluation.

Patients were classified using WHO and RA sex-specific (BMI ≥24.7 kg/m2 in men; ≥ 26.1 kg/m2 in women) BMI categories [9]. We used 2008 Statistics Canada data to compare the obesity rates with the general Canadian population. Obese vs. non-obese groups were compared with t tests and chi-square for continuous and categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V21 and p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Data from 94 patients from Montreal and 106 from Winnipeg were included. Demographics and RA characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Prevalence of obesity

Using WHO criteria, 68 (34 %) RA patients were classified as obese (Table 2). Using RA thresholds, 112 (55 %) were classified as obese. With both classification methods, sociodemographic characteristics were similar between obese and non-obese groups, and the proportion of people classified as obese was much higher than in the adult Canadian population (25 %) [10]. Using WHO criteria, the risk ratio (RR) for obesity was 1.4 (95 % confidence interval [CI] 0.9, 2.2); more women than men were classified as obese (36 vs. 29 %, respectively; Fig. 1). Using RA thresholds, 55 % were classified as obese (RR 2.3; 95 % CI 1.5, 3.4); however, more men than women were obese (67 vs. 53 %, respectively).

Disease activity

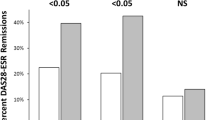

Using WHO criteria, ESR and CRP levels were significantly higher in obese individuals; and while DAS28 and tender joint counts also were higher, differences were not statistically significant. Using RA thresholds, disease activity indicators were similar between groups.

Patient-reported outcomes

With both classification methods, obese individuals had significantly higher mean HAQ scores (Table 2) and a higher odds of significant disability (i.e., HAQ ≥ 1: WHO OR 2.3; 95 % CI 1.2, 4.2 and RA-specific OR 1.8; 95 % CI 1.0, 3.2). Although morning stiffness, pain, and patient global scores were higher in obese patients with both classification methods, differences were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our results contribute to the growing body of evidence suggesting rates of obesity are higher in people with RA [3, 11]. Similar to others, one third of our sample (vs. ~25 % of Canadians) were obese using WHO criteria [3, 8, 9]. Using RA-specific criteria, two thirds of men and more than half of women in our sample were obese. With either weight classification system, obesity was associated with greater disability, and obese RA patients had about twice the odds of reporting moderate to severe disability (i.e., HAQ ≥ 1). A 2015 meta-analysis of BMI, disease activity, and selected RA outcomes, and a study of inflammatory polyarthritis, also reported greater disability among obese patients [4, 12]. Similarly, the increased disability we observed could be due to the higher prevalence of obesity in our sample. The complex interactions between patients’ health-related thoughts about arthritis and weight have been recently explored in a study by Sommers et al. showing that RA patients with higher levels of pain catastrophizing (i.e., tendency to focus on and magnify pain sensations and to feel helpless in the face of pain) and lower levels of confidence for managing (i.e., self-efficacy) both arthritis and weight were more likely to report higher levels of pain, poorer physical function, and more overeating [13]. Inflammatory indicators also were higher in obese persons using WHO (but not RA-specific) cut points. Several, but not all studies, have reported higher disease activity and greater pain and patient global scores in RA obese individuals [4, 14, 15]. Although DAS and tender (but not swollen) joint counts and PROs were higher in our sample, differences were not statistically significant in part due to smaller sample sizes.

Strengths of our study include the diverse sample of people with a wide range of BMIs (17–59). Participants were similar in age, pain, and disability to the sample on which the new RA cut points were derived, although our sample had more females, with shorter RA duration, and lower CRP. Our study has several limitations including the cross-sectional nature of the described associations and the lack of assessment of the impact of steroids, and other obesogenic medications. We did not specifically assess abdominal obesity, which is more strongly associated with negative health outcomes [16].

Given the deleterious effects of excess weight on health and quality of life [17], our results emphasize the importance of routinely identifying and addressing obesity in RA patients, and preventing weight gain in overweight individuals. It remains unclear whether weight loss can attenuate the excess CVD morbidity and mortality associated with RA, optimize response to treatment, and enhance physical function.

In summary, in a sample of Canadian RA patients, we found significantly higher rates of obesity and disparities in the prevalence of obesity by sex. Using traditional BMI cut points, one third of the RA patients were obese, and they had significantly higher levels of inflammatory markers and greater levels of disability. Using recently proposed RA cut points, two thirds of men and more than half of women with RA would be classified as obese. These results underscore the need to consider weight as one component of optimal disease management.

References

McCoy SS, Crowson CS, Maradit-Kremers H et al (2013) Longterm outcomes and treatment after myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 40:605–10

Crowson CS, Liao KP, Davis JM 3rd et al (2013) Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J 166(622–8):e1

Armstrong DJ, McCausland EM, Quinn AD, Wright GD (2006) Obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45:782, author reply −3

Vidal C, Barnetche T, Morel J, Combe B, Daien C (2015) Association of body mass index categories with disease activity and radiographic joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 42:2261–9

Sandberg ME, Bengtsson C, Kallberg H et al (2014) Overweight decreases the chance of achieving good response and low disease activity in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 73:2029–33

Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL (2014) Indices of relative weight and obesity. Int J Epidemiol 43:655–65

Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB et al (2006) Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med 355:763–78

Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, Koutedakis Y et al (2007) Redefining overweight and obesity in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 66:1316–21

Katz PP, Yazdany J, Trupin L et al (2013) Sex differences in assessment of obesity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 65:62–70

https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Obesity_in_canada_2011_en.pdf. Obesity in canada. A joint report from the public health agency of canada and the canadian institute for health information.

Giles JT, Ling SM, Ferrucci L et al (2008) Abnormal body composition phenotypes in older rheumatoid arthritis patients: association with disease characteristics and pharmacotherapies. Arthritis Rheum 59:807–15

Humphreys JH, Verstappen SM, Mirjafari H et al (2013) Association of morbid obesity with disability in early inflammatory polyarthritis: results from the norfolk arthritis register. Arthritis Care Res 65:122–6

Somers TJ, Wren AA, Blumenthal JA, Caldwell D, Huffman KM, Keefe FJ (2014) Pain, physical functioning, and overeating in obese rheumatoid arthritis patients: do thoughts about pain and eating matter? J Clin Rheumatol 20:244–50

Jawaheer D, Olsen J, Lahiff M et al (2010) Gender, body mass index and rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: results from the quest-ra study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 28:454–61

Giles JT, Bartlett SJ, Andersen R, Thompson R, Fontaine KR, Bathon JM (2008) Association of body fat with c-reactive protein in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 58:2632–41

Uutela T, Kautiainen H, Jarvenpaa S, Salomaa S, Hakala M, Hakkinen A (2014) Waist circumference based abdominal obesity may be helpful as a marker for unmet needs in patients with RA. Scand J Rheumatol 43:279–85

Heo M, Allison DB, Faith MS, Zhu S, Fontaine KR (2003) Obesity and quality of life: mediating effects of pain and comorbidities. Obes Res 11:209–16

Acknowledgment

Approximately 10 % of patients are also enrolled in the Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort (CATCH). CATCH study was designed and implemented by the investigators and financially supported initially by Amgen Canada Inc. and Pfizer Canada Inc. via an unrestricted research grant since the inception of CATCH. As of 2011, further support was provided by Hoffmann-LaRoche Ltd., UCB Canada Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada Co., AbbVie Corporation (formerly Abbott Laboratories Ltd.), and Janssen Biotech Inc. (a wholly owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson Inc.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colmegna, I., Hitchon, C.A., Bardales, M.C.B. et al. High rates of obesity and greater associated disability among people with rheumatoid arthritis in Canada. Clin Rheumatol 35, 457–460 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3154-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3154-0