Abstract

Purpose

Transabdominal pre-peritoneal hernia repair (TAPP) is a worldwide performed surgery. Surgical videos about TAPP uploaded on the web, with YouTube being the most frequently used platform, may have an educational purpose, which, however, remains unexplored. This study aims to evaluate the 20 most viewed YouTube videos on TAPP through the examination of four experienced surgeons and assess their conformity to the guidelines on how to report laparoscopic surgery videos.

Methods

On April 1st 2019, we searched for the 20 most viewed videos on TAPP on YouTube. Selected videos were evaluated on their overall utility and quality according to the Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills-Groin Hernia (GOALS-GH) and the Laparoscopic surgery Video Educational Guidelines (LAP-VEGaS).

Results

Image quality was poor for 13 videos (65%), good for 6 (30%) and in high definition for 1 (5%). Audio and written commentary were present in 55% of cases, while no video presented a detailed preoperative case description. Only 35% of the videos had a GOALS-GH score > 15, indicating good laparoscopic skills. Overall video conformity to the LAP-VEGaS guidelines was weak, with a median value of 12.5% (5.4–18.9%). Concordance between the examiners was acceptable for both the overall video quality (Cronbach’s Alpha 0.685) and utility (0.732).

Conclusions

The most viewed TAPP videos available on YouTube in 2019 are not conformed to the LAP-VEGaS guidelines. Their quality and utility as a surgical learning tool are questionable. It is of upmost importance to improve the overall quality of free-access surgical videos due to their potential educational value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

More than 20 million groin hernias are operated on every year worldwide [1]. The incidence of groin hernia is 27–43% in men and 3–6% in women, and the specific incidence rates vary among countries, ranging from 100 to 300 per 100,000 population/year [2] Inguinal hernia is often symptomatic and the only treatment is surgery. Additionally, in asymptomatic patients, a watch-and-wait approach results in surgery in 70% of cases within 5 years [3]. Beyond the open techniques, other managing procedures have been developed over time. Minimally invasive procedures, such as trans-abdominal retroperitoneal (TAPP) and total extraperitoneal (TEP) repair, were developed in the early 1990s. Currently, laparoscopy represents a valid alternative to traditional open techniques [4], with a learning curve for TAPP procedures that is estimated at approximately 50–75 surgeries [4].

The technical steps of the procedure were published by the International Endohernia Society in 2011 [5] and updated in 2015 [6], with the intention of highlighting the critical points of the surgery to be followed at all times.

The HerniaSurge Group works to disseminate and implement of the groin hernia management guidelines throughout the world, through modern multimedia, network tools and other methods [1]. The advantages of multimedia tools, such as videos, to familiarise surgeons with surgical procedures have been proven [7]. However, the most reliable video sources are often unknown or unavailable to surgeons, particularly residents and young surgeons. Thus, they often rely on unofficial distribution channels of surgical videos, the quality of which is not always guaranteed [8].

YouTube is one of the most visited sites on the internet, and it has been proven to be the most used source for surgical learning videos [7], mainly due to the availability of a large variety of freely accessible videos. However, video quality and content are not peer-reviewed or assessed prior to the upload on the web [9]. A previous study evaluating appendicectomy videos available on YouTube showed that the quality and conformity guidelines of these videos are rarely respected [8].

The Laparoscopic surgery Video Educational Guidelines (LAP-VEGaS) was published in 2018 with the aim of improving the quality of surgical videos with an educational purpose [10]. Moreover, several tools were proposed to help judge the quality of the displayed surgery, the surgeon’s skills and the conformity to procedural and safety principles. Among them, the Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills (GOALS) is a useful measure to assess generic laparoscopic skills [11]. The Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills-Groin Hernia (GOALS-GH) [12], an evolution of GOALS, is a procedure-specific evaluation tool for advanced surgery such as TAPP.

The aim of the present study was to assess the quality of the 20 most viewed videos on TAPP surgery uploaded on YouTube by evaluating: (1) conformity to LAP-VEGaS guidelines; (2) GOALS-GH scores as assessed by four senior surgeon examiners, and (3) conformity to the technical steps of the International Endohernia Society.

Methods

Study design

YouTube (https://www.youtube.com) was searched on 1st April 2019 using the search terms ‘TAPP surgery’ and ‘Trans-Abdominal Preperitoneal Hernia Repair’. Videos were sorted by number of visualisations, and the first 20 most viewed videos were selected if they were presented and/or commented in English, and if they displayed a live surgery recorded by laparoscopic camera. Cartoons and schematised videos were not considered.

The present study is based exclusively on the evaluation of public-domain videos and no ethical approval was necessary. The video characteristics assessed during the evaluation process are reported in Table 1.

Evaluation of surgical quality and educational utility

The conformity of each video to the LAP-VEGaS guidelines and to the International Endohernia Society technical steps was assessed by an independent examiner (E.R.). All other authors agreed with the independent author’s assessment.

Conversely, the GOALS-GH assessment was carried out independently and blindly by four senior surgeons (N.deA; G.C.; M.C.; J.L.) with expertise in laparoscopic hernia repairs (> 100 procedures). As only videos on TAPP surgeries were considered, the GOALS-GH scale item on TEP was not applicable. Thus, the GOALS-GH for TAPP surgery consisted of five items as described in Table 1. Each item was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 worst to 5 best).

Overall video quality was rated as good/moderate/poor, while overall video utility as an educational tool was scored using a 5-point Likert scale (1 useless to 5 very useful). Additionally, video quality and utility were rated independently by the four senior surgeons.

Data analysis

Data were recorded in a computerised spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2016; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond; WA) and analysed with statistical software (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Categorial variables were reported as percentages (%) and frequencies (n), while continuous variables were reported as a median or media (range/standard deviation). Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to determinate the consistency among examiners (a value ≥ 0.7 was considered acceptable agreement). The Spearman rank correlation coefficient (Spearman rho) was calculated to assess the degree of correlation between the considered variables. Factors associated with the overall video quality were identified with a binary logistic regression.

Results

Videos selection and characteristics

Videos on TAPP surgery posted on YouTube were sorted by order of visualisations. After duplicates were removed, the 20 most viewed videos that met the inclusion criteria were selected (Table 2). Thirteen videos were made in Asia (65%), one in Europe (5%) and one in South America (5%); whereas, the origin was unknown for five videos (25%). A total of seven videos were made by surgeons in tertiary care hospitals/academic institutions.

Videos were available online for an average of 1986 days (442–3871 days). The mean video length was 12.30 min (SD 13.38 min; 2–66 min). Videos received a mean of 22.7 comments (0–94 comments), a mean of 157.55 likes (11–537 like) and a mean of 21.75 dislikes (1–140 dislikes).

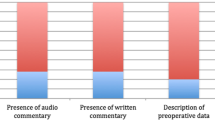

The image quality was rated as good in six videos (30%), poor in 13 (65%) and high definition in one video (5%). Audio and written commentaries were present in 55% of cases; whereas, no video presented a detailed preoperative case description.

LAP-VEGaS conformity

Video conformity to LAP-VEGaS guidelines is displayed in Table 3. The evaluation showed that all videos reported the surgical procedure in a step-by-step fashion (LAP-VEGaS item 17) and the number of comments and the number of views were available for all (LAP-VEGaS item 37). An audio or written English commentary was reported in 55% of the videos (LAP-VEGaS item 26) and the intraoperative findings were explained with a constant reference to anatomy in 80% of the videos (LAP-VEGaS item 18). However, the majority of the LAP-VEGaS items were not presented in the videos (n = 29 items; 78.37%). The highest percentage of conformity was observed for videos #3 (18.9%). The overall conformity of the videos to the LAP-VEGaS guidelines was weak, with a median value of 12.5% (5.4–18.9%).

There was a positive although weak correlation between the percentage of conformity to LAP-VEGaS guidelines and the number of likes (rho 0.357; p = 0.122), the number of dislikes (rho 0.238; p = 0.311) and the number of comments (rho 0.378; p = 0.100).

GOALS-GH assessment

The GOALS-GH assessment is reported in Table 4. For each domain, the scores given by the different examiners are reported. The Cronbach’s alpha was very good for all domains (trocar; creating preperitoneal flap; hernia sac; mesh; knowledge of anatomy and flow procedure). The overall internal consistency among the examiners was 0.848.

The overall score obtained by consecutive consensus among the surgeons was calculated for each video. Only seven videos (35%) reached a GOALS-GH score > 15.

Overall video utility and quality

The mean overall video utility was 2.61 (SD: 0.77). Consistency among examiners was good (Cronbach’s alpha 0.732). The video quality was scored as poor, moderate and good by the four examiners (Table 5). A 100% concordance among examiners was found for only one video (rates as poor), with an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.685. Consequently, by consensus, the selected videos were divided into two groups: moderate/good quality (n = 14) vs. poor quality (n = 6). The examiners were 100% in agreement in judging of 11/20 videos (55.0%) (Cronbach’s alpha 0.755). Through discussion with a fifth examiner (E.R.), a final grade was assigned to the remaining videos. Binary logistic regression was used to assess the correlation between overall video quality and video characteristics, conformity to LAP-VEGaS guidelines and GOALS-GH score (Table 6). A significant association was found between the video quality and the number of comments and likes, the presence of audio commentary, a GOALS-GH score > 15 and the mean utility score.

International Endohernia Society conformity

Video conformity to the 2011 and 2015 guidelines of the International Endohernia Society is displayed in Table 7. No video provides information about the type of centre where the intervention was performed (general information). The preoperative preparation of the patient and the operating room was never described. All videos described only the operating technique after inducing pneumoperitoneum and trocar positioning. All videos (100%) showed an adequate preperitoneal anatomical dissection and the excising en bloc of the hernia sac in 65% of cases.

Overall, 95% of the videos showed the closure of peritoneal incision, but only in 11 videos (55%), a running suture was performed. No video provides information on closing trocar incisions or postoperative pain management.

Discussion

The present study evaluates the quality of the 20 most viewed videos on TAPP surgery available on YouTube on 1st April 2019 and demonstrated that they are mostly of moderate to poor quality and utility.

Laparoscopic TAPP hernia repair was introduced 25 years ago and it is currently a well-defined surgical procedure with outcomes and complication rates directly related to the experience of the surgeon [4]. In general, the literature showed no differences between Lichtenstein and TAPP operation in terms of postoperative complications, but TAPP seems to be associated with less chronic inguinal pain postoperatively [13]. The TAPP learning curve is set at 50–75 procedures [14]. The senior surgeons involved in this study carried out more than 100 procedures. They were selected taking into account their expertise on hernia repair and TAPP technique, to make their judgement as objective as possible.

Recently, several studies have focused on the evaluation of surgical educational videos circulating through online networks, among which YouTube is the preferred channel [7]. Similar to what was reported in a previous study on the quality of laparoscopic appendectomy videos on YouTube [8], most videos on TAPP surgery (65%) have poor image quality, which may impair the utility of the videos as a learning tool [15, 16].

Important educational factors, such as audio or written commentary, are reported by the 55% of the selected videos. Poor-quality videos showed audio commentary more often (p = 0.024), but no significant differences were found between the two groups on the presence of written commentary (0.069). Unexpectedly, no video reported preoperative data such as patient characteristics or imaging data, although these data could be relevant to the surgery and the subsequent outcomes [4, 17].

Good- or moderate-quality videos showed a higher number of visualisation (p = 0.005), a longer video length (p = 0.051), a greater number of likes (p < 0.001) and dislikes (p = 0.009), and a higher utility score (p < 0.001) than did videos judged as poor in quality.

Only 35% of the videos had a GOALS-GH score > 15, indicating good laparoscopic skills, with good concordance levels among the four examiners. These results demonstrate an overall poor educational and technical value of the evaluated videos on TAPP surgery.

Lower concordance was found when the four examiners were asked to judge the overall video quality. Only one video (5%) was unanimously evaluated as poor in quality by the four surgeons. This finding can be partially explained by the 3-category scale chosen to assess video quality and the lack of a more detailed item-specific tool. In the absence of a validated measure, we opted for a purely categorical and qualitative assessment, which can be less practical when the evaluation is performed by multiple examiners. Conversely, a greater concordance rate was observed for video utility, which directly derives from the GOALS-GH assessment. Examiners were unanimous in their judgements of the majority of the poor-utility videos with an acceptable level of concordance (Cronbach’s alpha 0.732).

Only 35% of the videos showed good laparoscopic skills and no videos have an acceptable rate of conformity to the recently published LAP-VEGaS guidelines and to the International Endohernia guidelines. The overall agreement among the four senior surgeons who examined the videos was good. Finally, as expected, a very low rate of conformity to the recently published LAP-VEGaS guidelines was found for all TAPP videos.

Together, these data demonstrate that the most viewed TAPP videos available on YouTube in 2019 display procedures with unsatisfactory laparoscopic skills, in a highly heterogeneous way, with poor-quality imaging, thus having questionable utility as educational tools. This confirms previous findings on the topic [8, 18].

Laparoscopic groin hernia repair required skills in laparoscopic surgery and knowledge of pelvic anatomy to prevent complications [19]. Some of the patients’ characteristics, such as obesity (BMI > 35), ASA 3 or 4, complicated hernias (strangulated or incarcerated), anticoagulant therapy or history of previous pelvic surgery, could impact the difficulty of the surgical procedure [20, 21]. It is interesting to note, however, that none of the selected videos described these relevant preoperative data that would help the viewer to better understand the surgical steps and the surgeon’s challenges and choice, as pointed out in the guidelines of the International Endohernia Society [5, 6]. In the absence of these elements, the educational validity of these videos can be considered inadequate [8, 18, 22]. Moreover, it must be considered that uploaded videos are always edited, cut, and sped up. Consequently, the original course of the live surgery may be partially modified according to the purpose of the videos, which is not necessarily educational.

We must acknowledge that the present study considered only laparoscopic video on TAPP surgery uploaded to YouTube. This is the most popular video source among medical students and residents, but there are many other alternative sources, such as educational websites and social media platforms, that should be explored.

Conclusions

The most viewed TAPP videos available on YouTube in 2019 do not conform to the LAP-VEGaS and to the International Endohernia guidelines and their quality and utility as surgical learning tools are questionable. Public-domain surgical videos could be a very useful educational tool in general surgery, but they are currently not subjected to peer-review processes. It is of the upmost importance to improve the overall quality of freely accessible surgical videos due to their potential educational value. Surgical societies should support the creation of good educational videos and their open access publication, to allow the circulation of videos with high-quality standards.

References

Simons MP, Smietanski M, Bonjer HJ et al (2018) International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 22:1–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x

Kashyap AS, Anand KP, Kashyap S (2004) Inguinal and incisional hernias. Lancet 363:84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15211-7

Fitzgibbons RJ, Ramanan B, Arya S et al (2013) Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial of a nonoperative strategy (watchful waiting) for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Ann Surg 258:508–515

Lovisetto F, Zonta S, Rota E et al (2007) Laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) hernia repair: surgical phases and complications. SurgEndosc Other Interv Tech 21:646–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-006-9031-9

Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T et al (2011) Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)]. SurgEndosc 25:2773–2843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1799-6

Bittner R, Montgomery MA, Arregui E et al (2015) Update of guidelines on laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia (International Endohernia Society). Surg Endosc 29(2):289–321

Rapp AK, Healy MG, Charlton ME et al (2016) YouTube is the most frequently used educational video source for surgical preparation. J SurgEduc 73:1072–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.04.024

De’Angelis N, Gavriilidis P, Martínez-Pérez A et al (2019) Educational value of surgical videos on YouTube: quality assessment of laparoscopic appendectomy videos by senior surgeons vs novice trainees. World J EmergSurg 14:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-019-0241-6

Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, Gramopadhye AK (2015) Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Inform J 21:173–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458213512220

Celentano V, Smart N, McGrath J et al (2018) LAP-VEGaS practice guidelines for reporting of educational videos in laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg 268:920–926. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002725

Deal SB, Alseidi AA (2017) Concerns of quality and safety in public domain surgical education videos: an assessment of the critical view of safety in frequently used laparoscopic cholecystectomy videos. J Am Coll Surg 225:725–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.016

Kurashima Y, Feldman LS, Al-Sabah S et al (2011) A tool for training and evaluation of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: the global operative assessment of laparoscopic skills-groin hernia (GOALS-GH). Am J Surg 201:54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.09.006

Scheuermann U, Niebisch S, Lyros O et al (2017) Transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) versus Lichtenstein operation for primary inguinal hernia repair—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Surg 17(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-017-0253-7

Kuge H, Yokoo T, Uchida H et al (2019) Learning curve for laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal repair: a single-surgeon experience of consecutive 105 procedures. Asian J EndoscSurg. https://doi.org/10.1111/ases.12724

Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Lederman AB et al (2005) Video-assisted surgery represents more than a loss of three-dimensional vision. Am J Surg 189:76–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.04.008

Coull J, Weir PL, Tremblay L et al (2000) Monocular and binocular vision in the control of goal-directed movement. J Mot Behav 32:347–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222890009601385

Potomkova J, Mihal V, Cihalik C (2006) Web-based instruction and its impact on the learning activity of medical students: a review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 150(2):357–361

Celentano V, Browning M, Hitchins C et al (2017) Training value of laparoscopic colorectal videos on the World Wide Web: a pilot study on the educational quality of laparoscopic right hemicolectomy videos. SurgEndosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5504-2

Bracale U, Merola G, Sciuto A et al (2018) Achieving the learning curve in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair by Tapp: a quality improvement study achieving the learning curve in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair by Tapp: a quality improvement study. J InvestigSurg. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-017-0253-7

Suguita FY, Essu FF, Oliveira LT et al (2017) Learning curve takes 65 repetitions of totally extraperitoneal laparoscopy on inguinal hernias for reduction of operating time and complications. SurgEndosc Other Interv Tech 31:3939–3945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5426-z

Miserez M, Peeters E, Aufenacker T et al (2014) Update with level 1 studies of the European hernia society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 18:151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-014-1236-6

Frongia G, Mehrabi A, Fonouni H et al (2016) YouTube as a potential training resource for laparoscopic fundoplication. J SurgEduc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.04.025

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ER and NdeA contributed to the study conception and design. ER, MC, JL, GC contributed to material preparation, data collection, and video evaluations. ER performed statistical analyses and draft the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

For this type of study ethical approval is not required.

Human and animal rights

There are no human and animal rights issue to declare.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reitano, E., Cavalli, M., de’Angelis, N. et al. Educational value of surgical videos on transabdominal pre-peritoneal hernia repair (TAPP) on YouTube. Hernia 25, 741–753 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-020-02171-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-020-02171-0