Abstract

Purpose

Given the paucity of literature on outpatient ventral hernia repair (VHR), and that assessment of the safety of outpatient surgical procedures is becoming an active area of investigation, we have performed a multi-institutional retrospective analysis benchmarking rates of 30-day complications and readmissions and identifying predictive factors for these outcomes.

Methods

National surgical quality improvement project data files from 2011 to 2012 were reviewed to collect data on all patients undergoing outpatient VHR during that period. The incidence of 30-day peri-operative complication and unplanned readmission was surveyed. We created a multivariate regression model to identify predictive factors for overall, surgical, and medical complications and unplanned readmissions with proper risk adjustment.

Results

30-day complication and readmission rates in outpatient VHR were acceptably low. 3 % of the queried outpatients experienced an overall complication, 2.1 % a surgical complication, and 1.1 % a medical complication. 3.3 % of all patients were readmitted within 30 days. Upon multivariate analysis, predictors of overall complications included age, BMI, history of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and total operation time, predictors of surgical complications included age, BMI, total operation time, predictors of medical complications included total operation time, and predictors of unplanned readmissions included history of COPD, bleeding disorder, American Society of Anesthesiologists Class 3, 4, or 5, total operation time, and use of the laparoscopic technique.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the risk of peri-operative morbidity in VHR as granularly defined in our study is low in the outpatient setting. Identification of predictive factors will be important to patient risk stratification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Outpatient surgery is becoming an attractive alternative for select patients undergoing ventral hernia repair (VHR). The total cost of VHR for 2006 was reported to be 3.2 billion dollars while both the number of patients electing and dollars spent on inpatient status have risen [1]. Not surprisingly, most inpatient VHR procedures result in a net financial loss to the provider [2]. The cost disparity between inpatient and outpatient procedures has affected other surgical fields, to which they have responded by closely evaluating the viability of outpatient surgeries [3–8]. However, the economic promise of outpatient procedures must be carefully balanced against its peri-operative complication profile as patient safety is a higher priority than financial concerns. To date, there is a paucity of peer-reviewed literature directly benchmarking or evaluating rates of 30-day procedural complications or adverse events following outpatient VHR procedures [9].

The American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement project (NSQIP) is a nationally validated clinical registry that captures over 2 million patients in 400 institutions that has been previously used to evaluate safety in many surgical settings [3, 10–13]. Via the NSQIP database, we performed the first powerful multi-institutional retrospective analysis to accomplish two goals: (1) to benchmark the outcomes of outpatient VHR and (2) assess the safety of outpatient VHR procedures by identifying predictive factors for 30-day complications and unplanned readmission, after adjusting for other potentially confounding risk factors. We hope that our study will improve risk stratification and proper consent of patients undergoing outpatient VHR.

Methods

Population

The details of the ACS-NSQIP data collection methods have previously been described in detail and validated [14, 15]. Data files from 2011 to 2012 were reviewed to collect data on all patients undergoing VHR during that period. All patients who underwent ventral or incisional hernia repair were selected from the database based on primary current procedural terminology (CPT) codes and post-operative international classification of diseases (ICD)-9 diagnoses. The following primary CPT codes were included: 49560, 49561, 49565, 49566, 49568, 49570, 49572, 49580, 49582, 49585, 49587, 49590, 49652, 49653, 49654, 49655, 49656, 49657, and 49659. Any patient who underwent multiple procedures, identified by the presence concurrent CPT codes 15,734 (component separation) or 49,568 (use of mesh), were included in the sample. Last, the following ICD-9 codes were used to select only those patients whose post-operative diagnosis was a ventral or incisional hernia: 551.2, 551.21, 551.29, 552.2, 552.21, 552.29, 553.2, 553.21, and 553.29. Any patient with an ICD-9 other than those listed was excluded. Patients with a primary CPT code of 49652, 49653, 49654, 49655, 49656, 49657, or 49659 were considered to have undergone a laparoscopic procedure. All patients recorded to have received inpatient VHR were excluded, leaving only outpatients for analysis. NSQIP is only designed to detect if a given patient stayed in the hospital less than 23 h; NSQIP does not capture the initial inpatient/outpatient determination, nor conversions from inpatient to outpatient. Finally, outpatients were stratified by whether they experienced 30-day morbidity, as described in the next section, or not.

Variables

NSQIP-defined pre-operative variables were compared between cohorts. They included demographic variables (e.g., sex, age, BMI); lifestyle variables (e.g., smoking) and medical comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, dyspnea, wound class, previous sepsis, ventilator dependence, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), ascites, CHF, acute renal failure, dialysis, disseminated cancer, wound infection, steroid use, weight loss, bleeding disorders). Other operative characteristics captured included total operative time, total RVU for both primary and concurrent procedures, pre-operative transfusions, and emergency case. Total operative time and total RVU were treated as surrogates for case complexity [16].

Primary outcomes were categorized as surgical complications, medical complications, and overall complications. Surgical complications included superficial, deep, or organ–space surgical site infection [SSI] and wound disruption. Medical complications included deep venous thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), unplanned reintubation, ventilator dependence >48 h, progressive renal insufficiency, acute renal failure, coma, stroke, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction (MI), peripheral nerve injury, pneumonia, urinary tract infection (UTI), blood transfusions, graft/prosthesis/flap failure and sepsis/septic shock. All morbidities were used as defined in the NSQIP user guide. Overall complications included all surgical and medical complications. A tracked outcome that was not included in overall complications was unplanned readmissions, which was defined as an unplanned readmission to the same or another hospital for a post-operative occurrence likely related to the principal surgical procedure within 30 days of the procedure.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests, for categorical variables, and Student t test, for continuous variables, were employed to determine if differences in pre-operative clinical characteristics and demographics between cohorts were statistically significant. Significance was defined as P < 0.05. 30-day peri-operative complication and readmission rates were surveyed. A bivariate screen was then to employed to identify, via the inclusion criteria (n > 10, P < 0.2), peri-operative variables that were included in a multivariate regression model. The model identified predictive factors for overall, surgical, and medical complications and unplanned readmissions with proper risk adjustment. Again, P < 0.05 was considered significant. Hosmer–Lemeshow (H–L) and c-statistics were calculated to assess model calibration and discriminatory capability, respectively [17, 18]. All analysis was performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographics and comorbidities

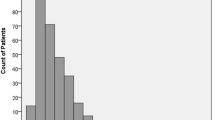

7666 patients were identified to have undergone outpatient VHR between 2011 and 2012; 15,873 total patients received VHR in this period. Table 1 compares pre-operative characteristics and demographics between patients who experienced any 30-day complication, as defined by overall complications, and patients who did not. Patients who sustained an overall complication were more likely to be American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Class 3, 4, or 5 (36.5 vs 45.8 %, P = 0.004), have an open wound infection (0.4 vs 2.2 %, P < 0.001), and have COPD (3.8 vs 7.00 %, P = 0.015), a higher BMI and longer operation time. The same comparison was made between patients who were and were not readmitted within 30 days (Table 2). Patients who had an unplanned readmission were more likely to have a higher BMI, undergone VHR with laparoscopic technique (3.00 vs 7.9 %, P < 0.001), be ASA Class 3, 4, or 5 (36.3 vs 49.8 %, P < 0.001), have dyspnea (6.1 vs 9.5 %, P = 0.027), COPD (3.8 vs 8.7 %, P < 0.001), acute renal failure (0.00 vs 0.8 %, P < 0.001), bleeding disorder (1.9 vs 4.7 %, P < 0.002), and experience weight loss (0.2 vs 2 %, P < 0.001).

Post-operative outcomes

30-day complication and readmission rates in outpatient VHR were low. 3 % of the queried outpatients experienced an overall complication, 2.1 % a surgical complication, and 1.1 % a medical complication. 3.3 % of all patients were readmitted within 30 days. Our study has established the following benchmarks for peri-operative events following outpatient VHR in a sample size of 7666 patients (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis

A regression model was employed to determine predictive factors of peri-operative morbidity following outpatient VHR, the results of which are displayed in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Variables that were included in the model were determined by a bivariate screen. Predictors of overall complications included age, BMI, history of COPD, and total operation time; predictors of surgical complications included age, BMI, total operation time; predictors of medical complications included total operation time; predictors of unplanned readmissions included history of COPD, bleeding disorder, ASA Class 3, 4, or 5, total operation time, and use of the laparoscopic technique.

Discussion

In light of the adoption of outpatient surgeries in many different surgical fields, and in the absence of retrospective data evaluating safety of outpatient VHR, we performed the first multi-institutional analysis of 7666 outpatients to establish benchmarks of 30-day complication and readmission rates, and identify predictive factors of these outcomes. Our studies suggest that rates of peri-operative morbidity following outpatient VHR are acceptably low, as none were higher than 3.3 %.

There is a paucity of literature regarding the safety of outpatient VHR. Outpatient surgeries have been reported to be associated with lower rates of serious morbidity and mean length of stay when compared to inpatient procedures [19, 20]. Abdel et al. reported success in laparoscopic repair performed in a single outpatient center with acceptably low risk and a recurrence rate of 5.04 % [9]. Fischer et al., via NSQIP data, reported a 3.9 % rate of major operative complications in outpatient abdominal wall repairs [21]. Many of these studies are limited by the single-institution sample size from which they were derived.

We found in our study that 2.1 % of patients experienced a surgical complication. Surgical site infections, in particular, have been a focal point in the movement for outcome-driven quality improvement in VHR [22–24]. Rates of 12 and 22 % have been previously reported for surgical site infections [22, 23]. However, these studies were performed in single-institution inpatient settings, and their findings may reflect greater inpatient case complexity. Rates of unplanned readmission were also very low in the outpatient setting. Readmission in VHR, well-known to be secondary to procedural complications, contributes to rising costs and patient morbidity [25, 26]. Our studies suggest that outpatient utilization is not a major part of the readmission problem.

Our findings must be interpreted in their proper context. We have demonstrated that the rates of 30-day overall, surgical, and medical complications and readmission are low in the outpatient setting. None of the queried patients experienced renal insufficiency, stroke, or an MI within 30 days of their VHR, suggesting that the clinical relevance of benchmarking these complications may be tenuous. Other outcomes (i.e., VTE, unplanned intubation) may not be clinically relevant to outpatient procedures [10]. Effort should be directed towards reducing surgical complications as it represents the majority of the post-operative morbidity burden in outpatient VHR. Our study suggests that referral to an outpatient setting is safe and appropriate. Our study also encourages uniformly accepted qualifications for outpatient repair, such as hernia size, patient comorbidity burden, and surgeon experience.

The second aim of our study was to identify predictive factors of adverse outcomes following outpatient VHR for risk stratification efforts. Total operation time was a common predictor of all tracked outcomes [21, 27–29]. BMI was significantly associated with overall and surgical complications, as has been previously described in studies evaluating surgical site infections [30, 31]. The laparoscopic approach, which has generated recent interest in outcomes studies, increased the risk of unplanned readmission [19, 24, 32–43].

While the ACS-NSQIP database provides a powerful platform and large sample size for our retrospective analysis, it is not without limitations [44, 45]. NSQIP is only designed to detect if a given patient stayed in the hospital less than 23 h, not the initial inpatient/outpatient determination [46]. For this reason, our results are not generalizable to a potential subset of patients who were initially designated as outpatient but experienced longer hospitalizations due to significant post-operative complications. This limitation may underestimate the complication rates for all outpatient cases. Hernia size, recurrence occurrences and rates, the reason for choosing the outpatient setting and other relevant endpoints such as post-operative pain, recovery time, and bugling are not captured by the database. The authors would like to highlight that a handful of outpatients were classified as ASA Class 4 and even fewer were recorded to undergo component separation with mesh. We attribute these findings to recording error, which is a limitation that plagues many multi-institutional registries, or exceptional cases. Still, recent evaluation of the NSQIP database suggests that the rate of inter-rater disagreement is only 1.56 %, making it highly reliable.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the risk of peri-operative morbidity in VHR as granularly defined in our study is acceptably low in the outpatient setting. We have also identified independent predictors of peri-operative morbidity in outpatient VHR. Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations and as the NSQIP database grows, future studies will either confirm or refute our conclusion on the low risk of outpatient VHR.

References

Poulose BK et al (2012) Epidemiology and cost of ventral hernia repair: making the case for hernia research. Hernia 16(2):179–183

Reynolds D et al (2013) Financial implications of ventral hernia repair: a hospital cost analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 17(1):159–166 (discussion p. 166–167)

Pugely AJ et al (2013) Outpatient surgery reduces short-term complications in lumbar discectomy: an analysis of 4310 patients from the ACS-NSQIP database. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38(3):264–271

Seybt MW, Terris DJ (2010) Outpatient thyroidectomy: experience in over 200 patients. Laryngoscope 120(5):959–963

Terris DJ et al (2013) American thyroid association statement on outpatient thyroidectomy. Thyroid 23(10):1193–1202

Rademacher J et al (2014) Safety and efficacy of outpatient bronchoscopy in lung transplant recipients—a single centre analysis of 3,197 procedures. Transplant Res 3:11

Carpelan A et al (2014) Reduction mammaplasty as an outpatient procedure: a retrospective analysis of outcome and success rate. Scand J Surg

Gillian GK, Geis WP, Grover G (2002) Laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair (LIVH): an evolving outpatient technique. Jsls 6(4):315–322

Abdel-Lah O et al (2005) Initial experience in the laparoscopic repair of incisional/ventral hernias in an outpatient-short stay surgery unit. Cir Esp 77(3):153–158

Khavanin N et al. (2014) Assessing safety and outcomes in outpatient versus inpatient thyroidectomy using the NSQIP: a propensity score matched analysis of 16,370 patients. Ann Surg Oncol

Lancaster RT, Hutter MM (2008) Bands and bypasses: 30-day morbidity and mortality of bariatric surgical procedures as assessed by prospective, multi-center, risk-adjusted ACS-NSQIP data. Surg Endosc 22(12):2554–2563

Khuri SF et al (2008) Successful implementation of the department of Veterans Affairs’ National Surgical quality improvement program in the private sector: the patient safety in surgery study. Ann Surg 248(2):329–336

Spaniolas K et al (2014) Early morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the elderly: a NSQIP analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis

Birkmeyer JD et al (2008) Blueprint for a new American College of Surgeons: national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg 207(5):777–782

Ingraham AM et al (2010) Quality improvement in surgery: the American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program approach. Adv Surg 44:251–267

Butler AR et al (2014) Laparoscopic hernia complexity predicts operative time and length of stay. Hernia 18(6):791–796

Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, Hall BL (2011) Interpretation of the C-statistic in the context of ACS-NSQIP models. Ann Surg Oncol 18(Suppl 3):S295 (author reply S296)

Paul P, Pennell ML, Lemeshow S (2013) Standardizing the power of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test in large data sets. Stat Med 32(1):67–80

Mason RJ et al (2011) Laparoscopic versus open anterior abdominal wall hernia repair: 30-day morbidity and mortality using the ACS-NSQIP database. Ann Surg 254(4):641–652

Bingener J et al (2007) Long-term outcomes in laparoscopic vs open ventral hernia repair. Arch Surg 142(6):562–567

Fischer JP et al (2014) Among 1,706 cases of abdominal wall reconstruction, what factors influence the occurrence of major operative complications? Surgery 155(2):311–319

Berger RL et al (2013) Development and validation of a risk-stratification score for surgical site occurrence and surgical site infection after open ventral hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg 217(6):974–982

Brahmbhatt R et al (2014) Identifying risk factors for surgical site complications after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: evaluation of the ventral hernia working group grading system. Surg Infect (Larchmt)

Liang MK et al (2013) Outcomes of laparoscopic vs open repair of primary ventral hernias. JAMA Surg 148(11):1043–1048

Lovecchio F et al (2014) Risk factors for 30-day readmission in patients undergoing ventral hernia repair. Surgery 155(4):702–710

Fontanarosa PB, McNutt RA (2013) Revisiting hospital readmissions. JAMA 309(4):398–400

Fischer JP et al (2013) Validated model for predicting postoperative respiratory failure: analysis of 1706 abdominal wall reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg 132(5):826e–835e

Kaoutzanis C et al (2013) Risk factors for postoperative wound infections and prolonged hospitalization after ventral/incisional hernia repair. Hernia

Dunne JR et al (2003) Abdominal wall hernias: risk factors for infection and resource utilization. J Surg Res 111(1):78–84

Breuing K et al (2010) Incisional ventral hernias: review of the literature and recommendations regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery 148(3):544–558

Birgisson G et al (2001) Obesity and laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias. Surg Endosc 15(12):1419–1422

LeBlanc KA, Booth WV (1993) Laparoscopic repair of incisional abdominal hernias using expanded polytetrafluoroethylene: preliminary findings. Surg Laparosc Endosc 3(1):39–41

Heniford BT et al (2003) Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias: nine years’ experience with 850 consecutive hernias. Ann Surg 238(3):391–399 (discussion 399–400)

Heniford BT et al (2000) Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair in 407 patients. J Am Coll Surg 190(6):645–650

Asencio F et al (2009) Open randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open incisional hernia repair. Surg Endosc 23(7):1441–1448

Gonzalez R et al (2003) Laparoscopic versus open umbilical hernia repair. Jsls 7(4):323–328

Hynes DM et al (2006) Cost effectiveness of laparoscopic versus open mesh hernia operation: results of a Department of Veterans Affairs randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg 203(4):447–457

Lomanto D et al (2006) Laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia mesh repair: a prospective study. Surg Endosc 20(7):1030–1035

Olmi S et al (2007) Laparoscopic versus open incisional hernia repair: an open randomized controlled study. Surg Endosc 21(4):555–559

Pring CM et al (2008) Laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. ANZ J Surg 78(10):903–906

Sains PS et al (2006) Outcomes following laparoscopic versus open repair of incisional hernia. World J Surg 30(11):2056–2064

Sauerland S et al (2011) Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:Cd007781

Zerey M, Heniford BT (2006) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for ventral hernia repair—which is best? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 3(7):372–373

Epelboym I et al (2014) Limitations of ACS-NSQIP in reporting complications for patients undergoing pancreatectomy: underscoring the need for a pancreas-specific module. World J Surg

Sippel RS, Chen H (2011) Limitations of the ACS NSQIP in thyroid surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 18(13):3529–3530

Khavanin N et al (2014) Predictors of 30-day readmission after outpatient thyroidectomy: an analysis of the 2011 NSQIP data set. Am J Otolaryngol 35(3):332–339

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial support

This particular research received no internal or external grant funding.

Ethical approval

De-identified patient information is freely available to all institutional members who comply with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Data Use Agreement. The Data Use Agreement implements the protections afforded by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and the ACS-NSQIP Hospital Participation Agreement, and conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, C., Hackett, N.J. & Kim, J.Y.S. Assessing the safety of outpatient ventral hernia repair: a NSQIP analysis of 7666 patients. Hernia 19, 919–926 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-015-1426-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-015-1426-x