Abstract

Surgical approaches to the head and maxillofacial area have been described and modified by many authors throughout history. It was, however, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries due in large part to improvements in the delivery of anesthesia and antibiotic therapy when most of the techniques were described. Currently, a myriad of surgical techniques are employed to access the maxillofacial complex with advantages and disadvantages for each one. Although each approach is described in many text and articles, few describe the circumstances or the historical context under which they were designed. In a series of three articles, a historical perspective will be provided on the evolution of some of the most commonly employed today. Descriptions will enumerate the advantages and disadvantages of as well as later modifications. The purpose of the present article (1/3) is to review the approaches to the head and upper face.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Techniques used to approach the maxillofacial complex have been recorded through the course of history and have evolved over time. Egyptian physicians were among the first to treat mandibular fractures and facial wounds about 4700 years ago [1]. Descriptions of ancient techniques from Occidental Europe and the Middle East were the foundations used throughout the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and Modern History for the development of today’s approaches. Wars have played a pivotal role. This was recognized by many, including Hippocrates (460B.c-370A.c), who stated “War is the only proper school for a surgeon” [1].

A surgical approach is the method employed to gain access to the site of the intended procedure. In other words, it is the technique used to enter the body to reach an anatomical area for adequate visualization, for the alignment of malposed parts or to remove disease. Options include incisions with dissection (open approaches), but can also include percutaneous ones via natural or artificial openings with or without an endoscope to manipulate displaced segments (closed techniques).

Currently, there are a plethora of approaches that are routinely used to gain access to the face. Each of them has advantages and disadvantages depending on the goals of the surgery. These techniques are the subject of many text and articles; but how and why were they developed? Under what circumstances were they designed? While most texts ignore the historical aspects of a surgical approach, we hope to provide that background for the most widely used approaches. We recognize that in our research, it is possible that some references/approaches are missing.

Materials and methods

An electronic search of the English, German, French, and Spanish literature was conducted. Searched databases included MEDLINE via PUBMED, EMBASE via OVID, LILACS, and SCIELO via BIREME. Secondary searching (PEARLing) was undertaken, whereby reference lists of the selected articles were reviewed for additional references not identified in the primary search. Additionally, table of contents of the following journals were reviewed: Mund-, Kiefer- und Gesichtschirurgie (Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery), Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology, British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, and International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Medical subject heading (MeSH) and the Spanish version of MeSH, Descriptores en Ciencias de la Salud (DeCS) were used for the search. Due to the nature and complexity of the paper, it is possible that some references may have escaped the searches.

Results

Current surgical approaches to the facial skeleton that are available in oral and maxillofacial surgery are countless and have been described in many languages throughout history. However, this was not always the case. Due to the lack of technology, resources, knowledge, or instruments, there were times in which surgeons had limited access to diseased areas. The present article is a historical review of today’s most commonly used approaches to the head and upper face. The approaches described in this article are depicted in Figs. 1, 2, and 3, and summarized in Table 1.

Surgical approaches to the head and upper face

The nineteenth century was characterized by an explosion of art, knowledge, science, and technology. Industrialization created new jobs and growth of cities and also led to rivalries among nations and empires. Improvements in communications and transportation systems and other developments resulted in political agitation that culminated in the World War I (1914 to 1918). While multiple facial injuries occurred, it was during the World War II (1939-1945) that surgeons who trained at Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup, south-east London, played a major role in the evolution of surgical techniques. Among them were Harold Gillies, Arthur Rainsford Mowlem, Archibald McIndoe, and Thomas Kilner. They developed techniques and surgical approaches to the face that survived the test of time.

Likewise, in Europe, many surgical approaches were designed, described, or modified by surgeons from France, Germany, and Italy. Therefore, most of the original reports are written in these languages. With the advent of local and general anesthesia, at the end of the nineteenth century, great strides were made with surgical approaches to the face. While there were a number of advocates for local and general anesthesia, Horace Wells and William Morton, both dentists from the USA, were leaders in the use of general anesthesia [2]. In 1864, the American Dental Association honored Wells as the discoverer of anesthesia as we know it today. Six years later, the American Medical Association recognized Wells’ achievement.

At the end of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century, surgeons from the USA took the lead and greatly contributed with the development of surgical approaches. Moreover, due to economic growth, many surgeons from all over the world relocated to the USA, bringing their skills and expertise with them [3].

Coronal

Other names | Bitemporal (Fig. 1a) |

Described by | Frank Hartley and James Kenyon |

Year | 1907 |

Reference | [4] |

Description | The coronal approach was originally employed for cerebral surgery by Hartley and Kenyon. The incision was performed over the glabella and extended laterally as needed. This flap provided great visibility; however, its downside was the great cosmetic defects that appeared after the wound healed. |

Modifications | Zigzag incision (Fig. 1b, dotted line) In 1995, Fisher et al. proposed a new coronal approach which they called the zigzag incision. Instead of a continued line, it was an incision following a zigzag pattern, which provided better healing properties and also had better cosmetic outcomes. It is now commonly used in trauma surgery and often referred as the “bicoronal approach”. They also stated that personal modifications could be made on a case by case basis. Some surgeons have opted to use a curvilinear instead reporting good results [5]. |

Gillies approach

Other names | None (Fig. 2a) |

Described by | Harold Gillies, Thomas Pomfret Kilner, Dudley Stone |

Year | 1927 |

Reference | [6] |

Description | Harold Gillies and colleagues proposed this extra oral approach to reduce zygomatic bone fractures in a minimally invasive way. They explained that the temporal area must be shaved; the incision should only be long enough to be able to enter the temporal space with a long instrument well suited to reduce the fracture. They stated this approach provided a cosmetic advantage, and was conservative due to the lack of great vessels and nerves in the temporal plane. This approach is still useful, especially when an intraoral approach cannot be performed. |

Modifications | None |

Retroauricular

Other names | None (Fig. 2b) |

Described by | Philipp Bockenheimer |

Year | 1920 |

Reference | Bockenheimer P. [7] |

Description | In 1920, German surgeon Philipp Bockenheimer developed a new, cosmetic method to expose the TMJ without injuring the facial nerve. |

Modification | Axhausen modification The retroauricular approach to the TMJ was first described by Bockenheimer and modified by Georg Axhausen in 1931. The incision is made posterior to the ear, followed by dissecting anteriorly with division of the auditory canal. Since this approach was very popular among German otolaryngologists, it is possible that Axhausen learned this method from his ENT colleagues and then adapted it for condyle access (Axhausen G. [8]). In 1969, Hiroshi Washio described a reconstructive flap and its harvest. He proposed the utility of a flap for defect reconstruction. He mapped the retroauricular and superficial temporal arteries and stated that custom modifications could be made depending on case by case basis [9]. More recently, in 2005, Neff and colleagues proposed a method to prevent cicatricial stenosis of the external auditory canal after TMJ surgery (Neff A, Meschke F, Kolk A, Horch HH. [10]). |

Temporal

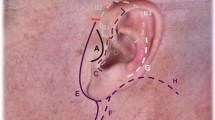

Other names | None (Fig. 2c) |

Described by | Hugo L. Obwegeser |

Year | 1985 |

Reference | [11] |

Description | Hugo Obwegeser first described this technique in 1978 during the 4th Congress of the European Association for Maxillo-Facial Surgery in Venice. He developed this approach to have a greater access to patients with extensive presentations of ankylosis and other TMJ afflictions. The incision starts in the most caudal point of the inner aspect of the tragus; then, it is continued upward and backward following the curvature of the helix for about 2 1/2 cm, from there it continues in a sharp angulation upward, about 2 cm posterior and parallel to the hairline, ending just above the lateral corner of the orbit. He stated that this approach provides excellent access and that it has a low probability of creating a scar; also, the risk of damage to neurovascular structures is very little. |

Modification | None |

Orbit, periorbit, and surrounding structures

As noted earlier, the advent of general anesthesia [2], the economic development of the USA, the World War I (1914 to 1918), the World War II, and other wars played a pivotal role in the development and refinement of surgical techniques. With most of Europe in ruins after the WWI and WWII, many surgeons moved to the USA in search of better opportunities [3]. Surgical approaches to the orbit were enriched by German surgeons who left central Europe and relocated to America at the end of the seventeenth century. This migration process continued during the nineteenth century with surgeons coming predominantly from Germany and in the twentieth century from the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

Among those who played an important role in the development and popularization of early approaches to the orbit is ophthalmologist and otolaryngologist Jacob Hermann Knapp (1832-1911). He earned his medical degree in 1854 from the University of Giessen and eventually became a member of the Eye Department in Heidelberg. He then migrated to America and organized the New York Ophthalmic and Aural Institute in 1869. A decade later, in 1879, he founded the American Archives of Ophthalmology, of which he was Editor and was succeeded by his son Arnold, who served until 1948.

Of note, lower lid percutaneous incisions (to be reviewed later) is not an approach per se. Rather, it is a generic term employed to a group of transfacial approaches to the lower lid, i.e., subciliar, subtarsal, and infraorbital. The approaches most commonly used to obtain access to the orbit are as follows:

Infraorbital

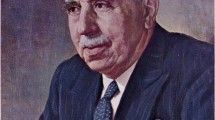

Other names | Inferior orbital rim, orbital rim approach, Dieffenbach incision (Fig. 3a) |

Described by | Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach (Fig. 2) |

Year | 1848 |

Reference | [12] |

Description | Dieffenbach proposed this approach to be able to access the orbit inferiorly. The incision is carried out in the infraorbital rim margin making the access very easy to accomplish. One of the downsides is a postoperative visible scar and edema due to the lymphatic drainage on this area. Interestingly, the infraorbital incision is one of the oldest approaches to the face. It was widely used during the nineteenth century; however, due to its cosmetic disadvantages, it was abandoned by contemporary surgeons. |

Modifications | None |

Anterior orbitotomy

Other names | None |

Described by | Herrmann Knapp |

Year | 1874 |

Reference | [13] |

Description | Knapp described the first approach to access the orbit. It consisted in an incision made in the unshaved eyebrow. After splitting the tarso-orbital septum, the periorbit was exposed and incised or lifted from the bone depending on the case. After the dissection, the development of ptosis was inevitable. The author stated that it usually lasted for about a few weeks; however, it could persist. |

Modifications | None |

Krönlein lateral orbitotomy

Other names | Lateral orbitotomy (Fig. 3b) |

Described by | Rudolf Ulrich Krönlein |

Year | 1889 |

Reference | [14] |

Description | Krönlein pioneered the lateral orbitotomy at the end of the nineteenth century. He described a crescent-shaped incision with an anterior convexity at the lateral orbital rim extending over the temporal fossa towards the ear. This approach proved to be useful at the time; however, the downside was the very notable scar formation after the patient fully healed, eventually modifications due to scar with the original incision. |

Modifications | Kocher lateral orbitotomy (Fig. 3c) Theodor Kocher developed a modified incision expecting to achieve better cosmetic outcomes. His approach started in the temporal half of the eyebrow, following the lateral margin of the orbit and bending over to the malar bone directed towards the lobe of the ear. The orbital margin was then freed from the periorbita and from the temporal muscle, by splitting the temporal fascia [15]. Modified Berke lateral canthotomy (Fig. 3d) In 1954, Raynold N. Berke modified the technique. He described an incision made at the lateral canthus and towards the ear, with an extension of 30-40mm. The external canthotomy was extended through the conjunctiva to the lateral orbital margin. Great access was achieved, and cosmetic outcomes were acceptable [16]. Stallard-Wright lateral orbitotomy (Fig. 3e) The approach developed by Henry Stallard in 1960 offered a slight modification of Wright’s technique. The incision started at the midline of the eyebrow, following it laterally and extending until reaching the level of the canthus, where it was extended laterally 10 more mm. He commented that it shared the advantages of the trans-frontal approach in which the lateral orbital wall was preserved and not nibbled away, and the orbital periosteum was reflected in two flaps and sewn up carefully at the end of the operation. Eight years later, he published another paper in which he recollected several approached to the orbit, including four incisions made to the eyelids for exploratory surgery [17,18,19]. |

Lynch

Other names | Lynch incision, frontoethmoidal (Fig. 3f) |

Described by | Ryan Lynch |

Year | 1921 |

Reference | |

Description | In 1921, Lynch proposed a new approach that allowed surgeons to access the frontal sinus. Chronic sinusitis had been a problem that was tackled with different approaches with little success. Lynch stated that a vertical semilunar incision starting medially to the supraorbital notch should be made extending below the medial canthus of the eye. The procedure consisted in removing the entire common sinus orbital wall (nasal process of superior maxilla, lower lateral edge of the nasal bone, lacrimal bone, and the entire lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone) and the middle turbinate allowing a complete curettage of the frontal-ethmoid-sphenoid complex. The author reported good outcomes in most of his cases; however, he noted that two of his patients had posterior wall necrosis with exposure of dura mater. One had an abscess causing exophthalmos. |

Modifications | Modified Lynch operation (Neel-Lake) (Fig. 3g) The Lynch operation was modified by Bryan Neel, James H. Whicker, and Clifford Lake in 1987. It was a less invasive surgical procedure with no risk of burying mucosa while giving direct access to the diseased ethmoid complex. Forehead sensation was usually preserved, and the incision was more acceptable cosmetically. The main difference of this approach was the preservation of the frontal process of the superior maxilla and normal mucoperiosteal lining in the region of the nasal-frontal communication and sinus. The incision was extended inferiorly to the midline of the eyebrow [22]. |

Comments | Sometimes this procedure is called the Lynch-Howarth approach, because of the two British surgeons. Also, distinction must be made between the Lynch incision and the Lynch procedure, also known as external frontoethmoidectomy. |

Transconjunctival

Other names | Inferior fornix incision; via either retroseptal or preseptal route (Fig. 3h) |

Described by | Julien Bourguet |

Year | 1924 |

Reference | [23] |

Description | In 1924, Bourguet described an approach for the removal of lower eyelid fat. It consisted in an incision made the length of the eyelid from a point behind the lacrimal punctum to the lateral canthus. It was performed 2-3 mm below the tarsus, where the conjunctiva and orbital septum are still somewhat adherent and incised simultaneously. Four years later, he described the approach in the context of eye bags (Bourguet J. [24]). |

Modifications | Transconjunctival with lateral skin incision or canthotomy (fornix incision and lateral canthotomy) (Fig. 3i) In 1973, John Converse and colleagues added a lateral incision to the transconjunctival approach improving the overall exposure. He also described two transconjunctival approaches; the preseptal and retroseptal depending on the dissection in relation with the orbital septum. Many surgeons believe the preseptal approach has fewer postoperative complications, while others believe the retroseptal is an easier approach with no major complications [25]. Lateral paracanthal incision (Fig. 3j) The transconjunctival approach with a lateral paracanthal incision is an alternative approach to the orbital wall. The decoupling of the lower eyelid through the lateral portion of the tarsal plate allows excellent exposure of the orbital floor and provides a reliable and consistent landmark by which the anatomy of the eyelid can be restored. It was described by Tristan M. B. de Chalain in 1994 in search of an approach to reduce postoperative complications [26]. |

Comments | Although this is a versatile approach for the orbit, Bourguet’s contemporaries did not use it routinely and it was somehow forgotten. More than 40 years later, Richard Tenzer and Gordon Miller rediscovered it and popularized it. (Tenzel RR, Miller GR. [27]). That is why some contemporary authors credit Tenzel et al., for the development of the transconjunctival approach. Two years later, Paul Tessier advocated its use for exposing the orbital floor and maxilla for the management of craniofacial dysostosis and traumatic injuries [28]. |

Subciliary

Other names | None (Fig. 3k) |

Described by | John Marquis Converse |

Year | 1944 |

Reference | [29] |

Description | In 1944, Converse developed an approach to correct orbital floor fractures that were very common during the WWII. His technique provided access to the lower rim and orbital floor at a time when the only other technique was the Kuhnt-Szymanowski approach. He stated that his approach provided good cosmetic results and correction of diplopia. |

Modification | None |

Subtarsal

Other names | Mid-lower eyelid incision (Fig. 3l) |

Described by | John Marquis Converse |

Year | 1944 |

Reference | [29] |

Description | Converse described a variant of his subciliary incision in the same article which is called the subtarsal approach. Its objective was the same, to be able to have access to the orbital floor and be able to repair fractures. This incision was made below the eyelid, over the infraorbital rim, and it provided good visibility and had less chances of flap rupture. |

Modifications | None |

Upper eyelid

Other names | Upper blepharoplasty; supratarsal fold |

Described by | Salvador Castañares |

Year | 1951 |

Reference | [30] |

Description | In 1951, Castañares developed an approach to eliminate herniated fat surrounding the eyelids. He stated that the incision lines in the upper eyelid should curve parallel to the curvature of the lid lying in the recess of the orbito-palpebral sulcus. The postoperative scar would become practically imperceptible. In the lower eyelid, the incision line should be made in a concave-convex crescent parallel also to the curvature of the lid. The incisions should be made 1-4 mm immediately below the lid margin and varying in length from a small central incision to one as long as from the level of one canthus to the other. |

Modifications | In 1960, Leabert R. Fernández noted that oriental patients had the desire to acquire the eyelid characteristics of western people. He described two approaches to achieve these goals depending on the desires of the patient. The first technique was named the “simple” approach, designed for patients that desired a small fold and that had little fat in their eyelids. He also described the “radical” approach. It was designed for patients with fatty eyelids. Both incisions are similar. The difference is that the radical approach splits the epicanthal fold and supraorbital fat was removed. Some of the postoperative complications include keratitis, ectropion, excessive swelling, discoloration, and hematomas [31]. Zigzag approach Robert S. Flowers developed a “zigzag” pattern based on existing resting skin tension lines and termed this method anchor blepharoplasty. He stated that this approach had better cosmetic outcomes, less scarring and less residual wrinkling [32, 33]. |

Vertical lid split orbitotomy

Other names | None (Fig. 3m) |

|---|---|

Described by | Byron Smith |

Year | 1966 |

Reference | [34] |

Description | Smith described this approach in a time when incisions that contacted the eyelid margins had a bad reputation due to the fear of residual marginal deformity. Smith felt this complication was due to the lack of fine instruments, fine sutures, good needles, and proper magnification. He proposed in an incision that crossed the lid margin through the tarsus skin and all lid elements to the depth of the fornix of either the upper or lower eyelid. He advised closing conjunctive with 5-0 plain catgut and orbicularis muscle with 6-0 chromic catgut or 6-0 buried silk. He concluded that with a careful manipulation of the tissues and a proper suture technique, no cosmetic defects should arise. |

Modifications | None |

Glabellar

Other names | Open sky (Fig. 1n) |

Described by | John Marquis Converse, Vincent Michael Hogan |

Year | 1970 |

Reference | [35] |

Description | In 1970, John Marquis Converse and Vincent Michael Hogan proposed the open sky approach. The objective was to be able to treat comminuted NOE fractures by direct vision. The approach consisted in an H-shaped incision which consisted of two lynch incisions connected with a transverse glabellar incision. They reported that the cosmetic outcomes were acceptable and that the access was of great use when this type of fractures were present. |

Modifications | Glabellar extended approach (horizontal Y approach) Interestingly, the glabellar extended approach (“horizontal Y approach”) is performed when the glabellar approach does not provide enough access to the medial canthal tendon area. The glabellar incision is extended from the lateral nasal bridge about 3mm medial to the skin edge of the caruncle. From there, it bifurcates into an upper and lower eyelid incisions. Modified glabellar (Fig. 3o) The modified glabellar approach was developed by Dong Jho et al. in 1997 in search of a microsurgical technique that allowed to excise lesions in the midline anterior skull base. The approach consisted in a 5-cm incision between the eyebrows. The incision started in the inferior medial border of one of the eyebrows and curved downward to a lateral point of the bridge of the nose. It then crossed the bridge of the nose and then curved upwards to mimic the first portion of the incision. They developed this approach in order to have a less invasive alternative. They reported a good cosmetic outcome and enough access to the desired lesion; however, with a bitemporal approach, the hidden scar is hidden in the scalp [36]. |

Transconjunctival medial orbitotomy

Other names | None |

Described by | James E. K. Galbraith and John H. Sullivan |

Year | 1973 |

Reference | [37] |

Description | Gallbraith proposed a fornix-based conjunctival flap of 180° fashioned on the nasal side of the globe and with radial incisions made at each end of the flap. Traction sutures are placed beneath the tendons of the superior rectus. The medial rectus is detached from the globe and a modified three-bladed tracheal dilator was inserted medially to the globe. Prolapse of the globe is performed and the optic nerve exposed. The subarachnoid space was then accessed. He reported good results. First employed to decompress the optic nerve and to relieve papilledema, De Wecker pioneered this operation in 1872, and he described a lower temporal conjunctival incision in which he was able to relieve papilledema. Subsequently in 1887, Carter proposed an approach through the conjunctiva over the lateral rectus, detaching its tendon. More recently in 1969, Smith et al. relieved unilateral disk swelling in a patient with a Kronlein orbitotomy [38,39,40]. |

Modifications | None |

Upper lid crease

Other names | None (Fig. 3p) |

Described by | Darrel E. Wolfley |

Year | 1985 |

Reference | [41] |

Description | The upper lid crease approach was developed by Wolfley in 1985. He stated that the approach provided great access to the orbital septum and levator aponeurosis. He noted that the distensibility of the skin would allow great retraction of tissues even beyond the medial extent of the incision. Finally, if any damage did occur to the lid structures, primary repair could easily be accomplished. |

Modifications | Upper lid crease with lateral extension (Fig. 3q) In 1999, Gerald J. Harris et al. proposed an upper lid crease incision with a lateral extension into an adjacent relaxed skin tension line for improved access. They stated that this approach is a good option to avoid bone flaps [42]. |

Superolateral orbital rim

Other names | Type I orbitotomy (Fig. 3r) |

|---|---|

Described by | Nakamura Yasuhisa |

Year | 1986 |

Reference | [43] |

Description | The superolateral approach to the orbit presents several advantages. It belongs to the osteoplastic orbitotomies which provide good cosmetic results. The exposure is larger than that of Krönlein’s orbitotomy; also, the operation is entirely performed extracranially. Finally, the skin incision may be reduced to a direct small incision when the patients are in poor clinical condition or when the patient is bald. |

Modifications | None |

Gull wing

Other names | Spectacle incision (Fig. 3s) |

Described by | Gustav Killian |

Year | 1903 |

Reference | Killian G. [44] |

Description | The gull wing incision has been used for several approaches throughout the face. We believe the first time the gull wing was performed on the upper third of the face was in the late nineteenth century by Gustav Killian. His objective was to expose the anterior skull base for lesion removal or frontal sinus surgery. |

Modifications | Eagle incision (Fig. 3t) The eagle incision was developed in 1991 by Nigel Beasley and Nick Jones. A horizontal incision was made through the eyebrow, and on reaching the lateral edge of the nasion, it was curved sharply downwards for 1 cm and then sharply up onto and over the nasion with an inverted “U” shape. They argued that this approach had better cosmetic outcomes [45]. Butterfly [46] |

Transcaruncular

Other names | None (Fig. 1k) |

Described by | Garcia GH |

Year | 1998 |

Reference | |

Description | In 1998, Garcia et al. developed a new approach for the medial orbit. They stated that the transconjunctival approach provided as much exposure as the Lynch approach and was more versatile because it could be combined with other incisions of the eyelid. Since the incision is performed in the conjunctiva, there is no risk of cosmetic. It is achieved with Stevens osteotomy scissors to create a vertical incision through the lateral quarter of the junction of the caruncle (8-10 mm superiorly and inferiorly through the conjunctiva); the periosteum along the posterior lacrimal crest is then incised with cautery. The authors reported no complications during or after procedure. |

Modifications | Extended transcaruncular approach (Fig. 3v) Recently in 2009, Rodriguez et al. developed the extended transcaruncular approach. The inferior incision must be made as low as possible in the inferior fornix with a retroseptal dissection to avoid the need to change planes. The orbital periosteum is cut 2 or 3 mm behind the inferior orbital rim and the conjunctival incision is made from the inferior to the medial fornix. The authors prefer a retroseptal dissection in contrast to Goldberg et al., to stay away from the lacrimal canaliculi. The advantages of this approach are that it has a better field of vision, larger mesh materials can be used, and it is easier to maintain hemostasis [49]. |

Comments | The transcaruncular approach was first designed by Henry I. Baylis in the late 1980s. However, it was properly published by Garcia et al. in 1998, and afterwards by Shorr et al. in 2000. In an article written by Goldberg (which was present in both publications) in 2007, he clarified that they all were working together when this approach was formally published, and he cites both authors as the creators of the approach; nonetheless, two publications exist. |

Conclusions

We have reviewed the history of the most commonly used surgical approaches to the head and upper face. The majority of these original references were published in English and French.

References

Laskin DM (2016) Oral and maxillofacial surgery: the mystery behind the history. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol 28:101–104

Prinz H (1945) Dental chronology. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia

Weinberger B (1948) An introduction to the history of dentistry. The C.V. Mosby Company, St. Louis

Hartley F, Kenyon JH (1907) Experiences in cerebral surgery. Ann Surg 45:487

Fisher DM, Goldman BE, Mlakar JM (1995) Template for a zigzag coronal incision. Plast Reconstr Surg 95:614–615

Gillies HD, Kilner TP, Stone D (1927) Fractures of the malar-zygomatic compound: with a description of a new X-ray position. Br J Surg 14:651–656

Bockenheimer P (1920) Eine neue Methode zur Freilegung der Kiefergelenke ohne sichtbare Narben und ohne Verletzung des Nervus facialis. Zentralbl Chir 47, 1560-1579

Axhausen G (1931) Die operative Freilegung des Kiefergelenks, Chirurg 3:713

Washio H (1969) Retroauricular-temporal flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 43:162–166

Neff A, Meschke F, Kolk A, Horch HH (2005) Prevention of cicatricial stenosis of the external auditory meatus in TMJ surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 34:23

Obwegeser HL (1985) Temporal approach to the TMJ, the orbit, and the retromaxillary–infracranial region. Head Neck 7:185–199

Dieffenbach JF (1848) Die Operative Chirurgie. F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig

Knapp H (1874) A case of carcinoma of the outer sheath of the optic nerve, removed with preservation of the eyeball. Arch Ophthalmol Otol 4:323–354

Krönlein RU (1889) Zur Pathologie and operativen Behandlung der Dermoidcysten der Orbita. Beitr z Klin Chir Tubing 4:149–163

Kocher T (1932) zitiert nach DeTakats: Surgery of the orbit. Arch Ophtalmol 8:259

Berke RN (1954) Modified Krönlein operation. AMA Arch Ophth 51:609–632

Stallard HB (1960) A plea for lateral orbitotomy with certain modifications. Br J Ophthalmol 44:718–723

Stallard HB (1968) Surgery of the orbit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 43:125–140

Wright AD (1948) Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K 68:367

Lynch RC (1921) The technique of a radical sinus operation which has given me the best results. Laryngoscope 31:1–5

Lynch RC (1929) Ethmoidal Sinusitis, External Radical Approach. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 34:438–445

Neel HB 3rd, McDonald TJ, Facer GW (1987) Modified Lynch procedure for chronic frontal sinus diseases: rationale, technique and long-term results. Laryngoscope 97:1274–1279

Bourguet J (1924) Les hernies graisseuses de l’orbite; Notre traitement chirurgical. Bull Acad Med Paris 92:1270–1272

Bourguet J (1982) Notre traitement chirurgical de ’poches’ sous les yeux sans cicatrice. Arch Prov Chir Fr Belg Chir 31:133–137, 1928

Converse JM, Firmin F, Wood-Smith D, Friedland JA (1973) The conjunctival approach in orbital fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 52:656–657

De Chalain TMB, Cohen SR, Burstein FD (1994) Modification of the transconjunctival lower lid approach to the orbital floor. Plast Reconstr Surg 94:877–880

Tenzel RR, Miller GR (1971) Orbital blowout fracture repair, conjunctival approach. Am J Ophthalmol 7:1141

Tessier P (1973) The conjunctival approach to the orbital floor and maxilla in congenital malformation and trauma. J Maxillofac Surg 1:3–8

Converse JM (1944) Two plastic operations for repair of orbit following severe trauma and extensive comminuted fracture. Arch Ophthalmol 31:323–326

Castañares S (1946) Blepharoplasty for herniated intraorbital fat. Anatomical basis for a new approach. Plast Reconstr Surg 46-58(1951):8

Fernández LR (1960) Double eyelid operation in the Oriental in Hawaii. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull 25:257–264

Flowers RS (1971) Zigzag blepharoplasty for upper eyelids. Plast Reconstr Surg 47:557–559

Flowers RS (1993) Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination. Anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 20:193–207

Smith B (1966) The anterior surgical approach to orbital tumors. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngl 70:607–611

Converse JM, Hogan VM (1970 Oct) Open-sky approach for reduction of naso-orbital fractures. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg 46(4):396–398

Jho HD, Ko Y (1997 Jun) Glabellar approach: simplified midline anterior skull base approach. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 40(2):62–67

Galbraith JE, Sullivan JH (1973) Decompression of the perioptic meninges for relief of papilledema. Am J Ophthalmol 76:687–692

de Wecker L (1872) On incision of the optic nerve in cases of neuroretinitis. Int Opthalmol Congr Rep 4:11

Carter RB (1887) Case of swollen optic disc, in which the sheath of the optic nerve was incised behind the eyeball. Proc Med Soc London 10:290

Smith JL, Hoyt WF, Newton TH (1969) Optic nerve sheath decompression for relief of chronic monocular choked disk. Am J Opthalmol 68:633

Wolfley DE (1985) The lid crease approach to the superomedial orbit. Ophthalmic Surg 16:652–656

Harris GJ, Logani SC (1999) Eyelid crease incision for lateral orbitotomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 15:916

Nakamura Y (1986) Osteoplastic orbitotomy for orbital tumor surgery. 5th International Symposium on Orbital Disorders, Sept. 1985, Amsterdam. Orbit 5, pp 235–237

Killian G (1903) Die Killian’sche Radicaloperation chronischer Stirnhöhleneiterungen: II. Weiteres kasuistisches Material und Zusammenfassung, Arch. f. Laryng. u. Rhin. 13:59

Beasley NJ, Jones NS (1995) A modification to the brow incision for access to the anterior skull base and paranasal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol 109:134–136

Ducic Y, Hom DB (1998) Reconstruction of frontal sinus. In: Rengachary SS, Benzel EC (eds) Fractures calvarial and dural reconstruction. Am Assoc Neurol Surgeons, Chicago, pp 107–118

Garcia GH, Goldberg RA, Shorr N (1998) The transcaruncular approach in repair of orbital fractures: a retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 4(1):7–12

Shorr N, Baylis HI, Goldberg RA, Perry JD (2000) Transcaruncular approach to the medial orbit and orbital apex. Ophthalmology 107(8):1459–1463

Rodriguez J, Galan R, Forteza G et al (2009) Extended transcaruncular approach using detachment and repositioning of the inferior oblique muscle for the traumatic repair of the medial orbital wall. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2:35–40

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sifuentes-Cervantes, J.S., Carrillo-Morales, F., Chivukula, B.V. et al. Historical evolution of surgical approaches to the face—part I: head and upper face. Oral Maxillofac Surg 26, 9–20 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-021-00953-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-021-00953-z