Abstract

Based on previous empirical evidences and theoretical framework, sleep problems and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)/suicidal behavior may bidirectionally related to one another. However, this still needs to be examined through longitudinal research. Moreover, the mediating mechanisms accounting for their potential bidirectional relations have yet to be fully investigated. This study thus aimed to evaluate whether sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior promoted each other directly or indirectly through the mediating roles of emotion regulation difficulties (ERD) and externalizing problems. A total of 1648 Chinese adolescents (48.12% boys; Mage = 13.69; SD = 0.82; Age range = 11–16 years old at T1) completed self-report measures on 3-time points across 1 year. Cross-lagged panel models were used to examine the focal longitudinal associations. Results revealed a predictive effect of sleep problems on NSSI and a positive bidirectional relation between sleep problems and suicidal behavior. Moreover, sleep problems exerted an indirect effect on NSSI through ERD, and vice versa. Additionally, both ERD and externalizing problems served as mediators in the pathway from suicidal behavior to sleep problems. This study disentangled the differential mediating roles of ERD and externalizing problems in the longitudinal associations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, which may help provide a more holistic theoretical framework through which to precisely identify key targets for early prevention and intervention of sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent studies have provided compelling evidence of a strong association between sleep problems and risky behaviors among adolescents [1], encompassing non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; the direct, self-inflicted damage of one’s own body tissue without the intent to die and for purposes that are not socially sanctioned [2]) as well as suicidal behavior (including suicidal ideation, suicide plans, suicide attempts, the threat of suicidal behavior, and the possibility of future suicidal behavior [3]). However, the majority of studies fail to elucidate the directionality of effects. It remains uncertain whether sleep problems contribute to an increased risk of NSSI/suicidal behavior or if NSSI/suicidal behavior reversely exacerbates sleep problems in adolescents. Furthermore, limited previous research has provided insight into the underlying mechanism that establishes a close link between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior among adolescents. To address the aforementioned limitations in the extant literature, the present study thus aimed to investigate if there is a reciprocal relation between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents, along with exploring the underlying mediating mechanisms.

Sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior

Sleep problems, which encompass a range of issues associated with sleep such as insomnia, hypersomnia, nightmares, and abnormal sleep–wake cycles, increase dramatically during adolescence [4] due to the occurrence of broad physical, psychological, and social changes in this period, which particularly facilitate adolescents’ susceptibility to NSSI/suicidal behavior. Both cross-sectional studies and meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated a positive association between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior among adolescents [5,6,7]. Furthermore, a limited number of longitudinal studies have provided partial support for these findings by demonstrating that sleep problems predict subsequent engagement in NSSI/suicidal behavior.

Despite the ample evidence of the effect of sleep problems on NSSI/suicidal behavior, most of the previous research failed to explore the possibility of bidirectional relations between them. Sleep problems are commonly believed to precede NSSI and suicidal behavior, with limited research exploring the possibility of NSSI/suicidal behavior affecting sleep problems [8]. Furthermore, little is known about the underlying mechanisms that may explain the potential reciprocal relations between these phenomena. Relatedly, Latina et al. [9] newly proposed a theoretical model that outlined a bidirectional relation between insomnia symptoms and NSSI. Specifically, they hypothesized that heightened depressive symptoms and impulsivity resulting from insomnia increase NSSI. Reversely, the shame associated with NSSI triggers repetitive negative thinking, further increasing insomnia. The study of Latina et al. [9] finally supported the bidirectional relations between insomnia and NSSI and the mediating role of depressive symptoms in the pathway from insomnia to NSSI.

Although informative, this study has several limitations that warrant further investigation in future research [9]. First, a sample of Swedish adolescents was taken as participants in the study. Given cultural variations, further studies are needed to replicate these findings in other populations from different cultural settings. Second, this study only focused on insomnia, which is merely a facet of sleep problem. Indeed, previous research has indicated that other sleep disturbances (e.g., nightmares, sleep deficits) are also closely related to NSSI/suicidal behavior [10, 11]. Therefore, future studies should test this model using sleep problems other than merely insomnia symptoms. Third, this study only investigated the relationship between insomnia and NSSI, while sleep problems are also tightly linked to suicidal behavior in adolescents [12]. Previous studies have revealed a strong correlation and frequent coexistence between NSSI and suicidal tendencies among adolescents [13, 14]. Furthermore, these two phenomena exhibit noteworthy similarity in terms of their psychological and pathological causes [15, 16]. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate whether a reciprocal relationship exists between sleep problems and suicidal behavior. Fourth, this study specifically focused on investigating depression, impulsivity, worry, and rumination as potential mediators. However, it is imperative for future research to enhance this model by broadening the understanding of potential mediators.

Given the aforementioned limitations of extant literature, this study aimed to investigate whether there are potential bidirectional relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior and to elucidate some of the underlying mechanisms that could account for these associations in a sample of Chinese adolescents.

ERD and externalizing problems as mediators

The longitudinal mechanisms underlying the relationship between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior have not been fully explored in previous research [9, 12]. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the potential bidirectional associations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior during adolescence, the present study aimed to investigate two potential mediators.

One possible mediator is ERD, which is defined as difficulties in identifying, understanding, and accepting emotions, controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed, and flexibly modulating emotional responses as situationally appropriate [17]. On one hand, the bidirectional relations between sleep and emotions have been addressed in a review utilizing an abundance of empirical evidences. Specifically, Kahn et al. [18] put forward the notion of a “vicious cycle” whereby sleep disturbances undermine the ability to regulate emotions, often resulting in heightened negative emotions that subsequently disturb sleep, further deteriorating emotional well-being. On the other hand, a bidirectional relation was also revealed in a previous study such that poor emotion regulation predicted future engagement in NSSI, while involvement in NSSI forecast subsequent declines in emotion regulation [19]. This bidirectional risk relation implies that adolescents resort to NSSI due to poor emotion regulation, and importantly, this behavior may further impair their capacity to regulate emotions. Take together, it was plausible to hypothesize that ERD would mediate the potential bidirectional relations between sleep problems and health-risk behavior, including NSSI and suicidal behavior. Namely, sleep problems may increase subsequent ERD, which consequently leads to the emergence of NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents. Conversely, engaging in NSSI/suicidal behavior may render adolescents more likely to have difficulties in emotion regulation, and thus develop sleep problems.

Furthermore, some previous studies have investigated the unidirectional mediating impact of emotion regulation on the correlation between sleep and NSSI/suicidal behavior, which indicates the necessity for further exploration of the bidirectional mediating effect of ERD in the longitudinal relations between NSSI/suicidal behavior. For instance, a study of 152 undergraduates indicated that emotional dysregulation played a fully mediating role between nightmares and NSSI [10]. Similarly, a study with a sample of 40 American adolescents reported that emotion dysregulation fully accounted for the relationship between insufficient sleep and NSSI [20]. Additionally, another study among 972 Turkish adults indicated that emotion regulation mediated the direct effect of nightmares on suicide risk and suicide attempts [21]. Considering that the previous studies only employed cross-sectional research designs to examine the unidirectional mediating effect of emotional regulation, this study aimed to further investigate the potential bidirectional mediating role of ERD in the relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behaviors.

Another possible mediator is externalizing problems, which refer to various types of maladaptive behaviors such as aggression, hyperactivity/inattention, and conduct problems [22]. There has been limited research examining the mediating role of externalizing problems in the relationship between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior. Despite the lack of direct evidences, previous studies have provided relevant evidence for the possible bidirectional mediating effect of externalizing problems between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior. For one thing, previous longitudinal studies have revealed bidirectional relations between sleep problems and externalizing problems/behavioral problems in children samples [23, 24]. For another, previous research has suggested the close links between externalizing problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior. For instance, a review of 35 studies suggested that externalizing problems in NSSI groups were significantly higher than in control groups, and the patients with conduct problems had higher prevalence rates of NSSI [25]. Another study of 20,702 Chinese adolescents also indicated that adolescents with single or multiple suicide attempts presented more externalizing problems [26]. The aforementioned cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings have highlighted the need to further examine the directionality of the association between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, as well as whether externalizing problems would function as a bidirectional mediator within these relations. Specifically, it also seemed reasonable to hypothesize that sleep disturbances have the potential to compromise adolescents’ capacity to regulate impulsivity [27], resulting in challenges such as inattention, aggression, and deviant behavior [28]. These problematic behavior may further heighten their susceptibility to developing self-injurious behaviors and suicidal tendencies. Conversely, research indicates that adolescents who engage in self-harming behaviors usually report elevated levels of physiological responsiveness when confronted with stress, along with difficulties in deliberative decision-making [29], which are associated with an increased risk of externalizing problems. Consequently, these externalizing problems may, in turn, impede adolescents from attaining and sustaining restful sleep [23].

Overall, although multiple cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have established that sleep problems, ERD, externalizing problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior are closely associated with one another, the directionality and underlying mechanism of these associations remain unclear. Therefore, the present study sought to investigate whether the hypothesized vicious cycle between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior would be driven by ERD and externalizing problems, which would help inform the focus and timing of prevention and interventions.

The current study

This study aimed to explore how sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior concurrently and longitudinally influence one another, as well as how they are related to ERD and externalizing problems in adolescents. Based on the extant literature, two related hypotheses were formulated: (a) Positive bidirectional relations would exist between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior; (b) ERD and externalizing problems would function as mediators in the bidirectional relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior. Given that age, gender, and family socioeconomic status (SES) have been proven to be potential contributors to the study variables [30, 31], they were addressed as covariates, and gender differences were further analyzed in this study.

Methods

Participants

A total of 1648 Chinese adolescents (48.12% boys; Mage = 13.69; SD = 0.82; Age range = 11–16 years old at T1) in junior middle school were recruited in a city located in Guangdong province, China. Of the participants at Time 1, 48.00% were in Grade 7 (Mage = 13.33; SD = 0.70), and 52.00% were in Grade 8 (Mage = 14.09; SD = 0.74). With regard to paternal education level, 77.88% attained a junior high school or below; 18.30% attained a high school or technical secondary school education, and 3.82% attained a bachelor degree or above. As for maternal education level, the percentages were about 82.14%, 15.54% and 2.32%, respectively. The participants completed three assessments over 1 year with six-month intervals. Of the participants at Time l, 96.54% (1591), 93.63% (1543) retained in this study from Time 2 to Time 3, respectively. Attrition was mainly attributed to changing schools, sick leave or private affairs leave during the assessment.

A normed chi-square (χ2/df) of 1.21 (p < 0.001) was revealed by the Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test [32]. The χ2 is quite susceptible to the sample size, and a chi-square under 3.0 is the accepted critical threshold, thus the current results implied that the pattern of the missing data in this study wasn’t essentially distinct from a random pattern [33]. Thus, Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) was used in data analyses in this study.

Procedures

The current study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Education School, Guangzhou University and the relevant school boards, principals, and teachers. Student assent and parents’ informed content were obtained before data collection. Self-report measures were administered to participants in the regular classroom environment by trained graduate assistants during assessments. Participants were informed of the general nature of this study and promised that their responses would be treated confidentially. Moreover, participants could take as much time as needed to complete the measures and withdraw from the study at any time.

Measures

Sleep problems

Sleep problems were assessed with the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [30], which is a self-reported questionnaire comprising 19 items. The PSQI evaluates seven dimensions of sleep during the past month: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, uses of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each dimension was rated from 0 to 3, and total scores for the seven dimensions were calculated, with higher total scores indicating higher levels of sleep problems. The PSQI has shown satisfactory reliability and validity in Chinese adolescents [31]. The Cronbach’s coefficients α for PSQI in this study were 0.72, 0.76, 0.81 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively.

Emotion regulation difficulties

ERD was measured by the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF), which is derived from the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) [17]. DERS-SF consists of 18 items combined into 6 dimensions: nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and labeled lack of emotional clarity. Each item was rated from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), and total scores for the 18 items were calculated, with a higher total score indicating a highers level of ERD. Previous studies have indicated good reliability and validity for DERS-SF among Chinese adolescents [34]. The Cronbach’s coefficients α for DERS-SF in this study were 0.87, 0.89, 0.88 for T1 to T3, respectively.

Externalizing problems

Externalizing problems were measured through two subscales from Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [35], including hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems. Each subscale includes five self-reported items which are rated on a 3-point Likert scale, from 0 = “unlike me” to 2 = “very much like me”. The possible score range for each subscale is 0–10, and total scores for the two subscales were calculated, with a higher total score indicating a highers level of externalizing problems. The Chinese version of SDQ has shown satisfactory psychometric properties in Chinese adolescents [36]. The Cronbach’s coefficients α for SDQ in this study were 0.77, 0.81, and 0.84 for T1 to T3, respectively.

Non-suicidal self-injury

The current study assessed seven NSSI behaviors chosen from the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI) [37], including self-cutting, burning, biting, punching, scratching, inserting sharp objects into nail or skin, and banging the head or other parts of the body toward the wall. Previous studies have shown that the above NSSI behaviors were relatively common among adolescents, and they had been used to evaluate NSSI in Chinese youth in prior studies [38]. Participants were asked “In the past year, have you deliberately harmed yourself (without suicidal intent)?” Besides, considering that the measurement interval in this study was six months, we have changed the phrase “in the past year” to “in the past six months” in the questionnaire used at T2 and T3. The seven items were rated on a 4-point scale, from 1 (‘never’) to 4 (‘six times or more’), with higher total score indicating higher levels of NSSI. This scale has shown sufficient concurrent and overtime validity in Chinese youth [38]. The Cronbach’s coefficients α for this scale in this study were 0.85, 0.87, and 0.90 for T1 to T3, respectively.

Suicidal behavior

The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised [3] was used to assess suicidal behavior in the past year among participants in this study. The SBQ-R consists of four items, evaluating four dimensions of suicidal behavior: lifetime suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt; the frequency of suicidal ideation over the past twelve months; the threat of suicidal behavior; and self-reported likelihood of suicidal behavior. Besides, considering that the measurement interval in this study was six months, we have changed the phrase “over the past twelve months” to “over the past six months” in the questionnaire used at T2 and T3. The four items are rated based on the severity of the behaviors reported, with a higher total score indicating higher levels of suicidal behavior. This scale has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in Chinese youth [39]. The Cronbach’s coefficients α for SBQ-R in this study were 0.73, 0.75, and 0.79 for T1 to T3, respectively.

Covariates

Participants’ self-reported gender, age, and SES at T1 were included in the modeling analysis as covariates. As the most stable and common aspect of SES [40], parental education levels, including maternal and paternal levels, was addressed as covariate in this study. There were eight options from 1 (never to school) to 8 (doctoral degree), with higher average paternal and maternal education levels representing higher SES.

Statistical analyses

First, preliminary analyses were conducted in SPSS 22.0.

Second, Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the longitudinal measurement invariance of the relevant measures. Changes in the Comparative Fit Index (ΔCFI) that did not exceed a threshold of 0.01 and changes in Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (ΔRMSEA) that did not exceed a threshold of 0.015 were considered indicative of invariant measurement [41].

Third, given that the purpose of the current study is to investigate the prospective effects of between-person differences among sleep problems, ERD/externalizing problem, NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents, standard Cross-Lagged Panel Models (CLPMs) were applicable to examining the focal associations, based on the suggestion proposed by Orth et al. [42]. CLPMs are valuable for comprehending the longitudinal and reciprocal associations among constructs, and due to their ability to account for continuity in the constructs over time, they can be considered as optimal yet cautious tests of development processes and directions of associations [23, 43]. Due to these strengths, CLPM is still widely used to investigate the longitudinal relations among study variables [44,45,46]. The CLPMs included auto-regressive paths, concurrent covariances, and cross-lagged paths. Specifically, auto-regressive paths indicated stability coefficients for each study variable; concurrent associations represented associations within the same time; and cross-lagged paths indicated reciprocal relations among the study variables. Participants’ gender, age, and SES at T1 were included in all CLPMs as time-invariant covariates and were regressed on all variables at each time point.

Fourth, bias-corrected bootstrapping on the basis of 1000 samples was used to assess the significance of indirect paths with the bias-corrected confidence intervals [47]. The indirect effect was statistically significant at the 0.05 level if the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect excluded zero. Control variables were also included in the bootstrapping analyses.

Fifth, a multi-group approach was used to test whether the focal associations varied by gender. The multi-group approach has often been conducted to examine gender differences in associations among study variables in previous studies [48,49,50]. Two models were compared separately: (1) An unconstrained model with all path coefficients allowed to be unequal across gender, and (2) A constrained model with all path coefficients constrained to be equal across gender. For model comparisons, a value of ∆CFI smaller than or equal to 0.01 indicated a non-significant difference [51].

All these analyses were conducted in Mplus 8.0. Research data were included in the model as observed variables. The model fit was considered adequate when the comparative ft index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were close to or above 0.90 [52], while the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were lower than 0.08 and 0.10, respectively [53].

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for the study variables are shown in Table 1. The correlations among the key variables were all statistically significant within and across waves.

Longitudinal measurement invariance

As presented in Section 1 of the Supplementary Materials, all measures showed sufficient measurement longitudinal invariance.

Results of cross-lagged panel models

As presented in Table 2, all the CLPMs indicated satisfactory model fits.

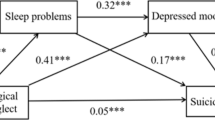

As shown in Fig. 1, there were significant bidirectional relations between sleep problems and ERD, and between ERD and NSSI. However, no bidirectional relations existed between sleep problems and NSSI. As shown in Fig. 2, there were bidirectional relationships between sleep problems and ERD, ERD and suicidal behavior, as well as sleep problems and suicidal behavior, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, there were significant bidirectional relations between sleep problems and externalizing problems. However, no bidirectional relations existed between externalizing problems and NSSI, sleep problems and NSSI, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, there were significant bidirectional relations between sleep problems and externalizing problems, sleep problems and suicidal behavior, respectively. However, no bidirectional relations existed between externalizing problems and suicidal behavior.

The indirect paths

As presented in Table 3, results revealed that: (1) The indirect path from T1 sleep problems to T3 NSSI via T2 ERD was significant, and the indirect path from T1 NSSI to T3 sleep problems via T2 ERD was significant; (2) The indirect path from T1 suicidal behavior to T3 sleep problems via T2 ERD was significant; (3) The indirect path from T1 suicidal behavior to T3 sleep problems via T2 externalizing problems was significant. All the remaining indirect paths were not statistically significant.

Gender differences

As shown in Section 2 of the Supplementary Materials, gender invariance analyses revealed non-significant differences in the focal longitudinal associations.

Discussion

The links between sleep problems, ERD/externalizing problems, NSSI/suicidal behavior already got some research attention. The present study went a step further and investigated whether sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior promoted each other directly or indirectly through the mediating roles of ERD and externalizing problems. The current findings elucidated the nature of focal longitudinal associations by revealing the differential mediating roles of ERD and externalizing problems in the relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents.

Relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior

As regards to the direction of effects between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, the current findings were partly consistent with our hypothesis. Specifically, on one hand, a direct predictive effect of sleep problems on NSSI/suicidal behavior was revealed. On the other hand, suicidal behavior exerted a negative impact on sleep problems, while NSSI did not show a significant effect on sleep problems in this study. Overall, these findings were in line with the results from the existing literature and further supported the close links between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, which could be comprehended through the lens of “overarousal” dimension proposed by Ribeiro et al. [54] according to the interpersonal theory [55]. Specifically, most individuals are discouraged from engaging in self-destructive behavior due to its inherently aversive nature. Self-destructive behavior necessitates the suppression of powerful self-preservation instincts, a feat that the majority of individuals are not naturally inclined to accomplish. Humans have evolved to experience increased arousal when confronted with potential dangers to survival, which equips them to either confront or evade the threat. Indeed, prior to a near-lethal or lethal attempt, individuals may frequently encounter behavioral and psychological overarousal—manifesting as restlessness, unease, preoccupation, and inner turmoil [56]. Especially, sleep disturbances are deemed as a symptom of acute states of heightened arousal, and have been consistently linked to self-destructive behavior. Considered within this framework, the findings of this study may suggest that as a facet of overarousal, sleep problems could manifest as a function of seriously strategizing and fixating on the possibility of engaging in self-destructive behavior, such as NSSI/suicidal behaviour. More importantly, not only does the risk of self-harm and suicide increase with the emergence of sleep problems, but conversely, when individuals are contemplating ending their lives, it further intensifies the state of heightened arousal, that is, the continuous deterioration of sleep problems. Therefore, this finding provides a noteworthy new perspective on the link between overarousal and suicide, suggesting that the state of overarousal and self-destruction may simultaneously arise and develop, giving rise to a vicious cycle connecting the two. Such insights are crucial for professionals dealing with sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behaviors among adolescents.

Additionally, inconsistent with the results from the study of Latina et al. [9], NSSI did not exert a significant predictive effect on sleep problems in this study, which may imply that the passive impact of suicidal behavior on sleep problems is more profound than that of NSSI. For one thing, in comparison to NSSI, suicidal behavior exposed adolescents to anxiety and fear directly related to death [57], which may cause more intense arousal in both their physical and psychological condition, resulting in greater vulnerability to sleep disturbances. For another, previous research has demonstrated that adolescents with suicidal behavior experienced higher levels of depression, lower self-esteem, and less parental support compared to those who only engaged in NSSI [58]. Thus, greater psychological distress and less social support may also render adolescents with suicidal behavior more susceptible to developing sleep problems than those engaging in NSSI. Nevertheless, discrepancies in measurement may also contribute to inconsistencies among research findings, including the selection of assessment instruments, duration of tracking measurements, and intervals between measurements. Therefore, future studies could employ alternative measurement tools and investigate the relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behaviors across diverse temporal frameworks, while also comparing the differences between the research results.

Overall, the present findings shed new light on the continuous unfolding of transactions between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents. The vicious cycle between sleep problems and suicidal behavior highlighted the significance of applying a developmental and transactional perspective to the prevention and interventions for adolescents sleep problems and suicidal behavior.

The mediating roles of ERD and externalizing problems

Regarding the mechanisms behind the links between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, this study revealed differential mediating roles of ERD and externalizing problems in the longitudinal associations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior.

In the first sequence, sleep problems exerted an indirect effect on NSSI via ERD, and vice versa. Moreover, ERD functioned as a mediator in the pathway from suicidal behavior to sleep problems, but not vice versa. Previous studies have revealed that sleep problems may render individuals more susceptible to emotional problems due to the intricate negative impacts it has on emotional brain networks, mechanisms related to REM sleep, and the processing of emotional information [18, 59]. Moreover, in line with the cognitive-energy model proposed by Zohar et al. [60], sleep problems, particularly sleep loss, exhaust energy levels, thereby disrupting the ability to respond adaptively to emotions and leading to difficulties in emotion regulation. Furthermore, individuals with inadequate abilities to regulate their emotions may encounter heightened negative emotions and became thoroughly immersed in them for longer periods [61], and finally are more likely to resort to NSSI as a strategy to alleviate intense emotions [62, 63].

Conversely, individuals who engage in NSSI will find it a quick and rewarding way to cope with distress [64]. As a result, they may become less tolerant of distress over time and rely on NSSI as a “quick fix” for overwhelming emotions. This decreased exposure to prolonged distress may increase sensitivity to challenging emotions and make the same event more distressing. Engaging in emotional avoidance behaviors, such as NSSI, leads to negative beliefs about one’s ability to regulate emotions [65]. NSSI can decrease self-efficacy in tolerating distress and utilizing other effective emotion regulation strategies, thereby damaging emotion regulation abilities [63]. Moreover, individuals with difficulties in emotion regulation may experience increased challenges in managing negative emotions and cognitive reactions resulting from NSSI, which can have serious influences on sleep [18]. Therefore, NSSI may exacerbate sleep disturbances in adolescents through intensifying their emotional regulation difficulties. Additionally, it was worth noting that in this study, ERD mediated the effect of suicidal behavior on sleep problems, but not the other way around. This finding was unexpected and contradicted previous studies that focused on adult participants [21, 66]. Given that this discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the study samples, future research should further investigate these relations using diverse study samples from various cultural contexts. To sum up, the aforementioned finding suggests that sleep problems directly impact suicidal behavior rather through the mediation of ERD; while suicidal behavior can facilitate sleep problems both directly and indirectly through exacerbating ERD.

In the second sequence, sleep problems did not exert an indirect effect on NSSI/suicidal behavior through externalizing problems in this study. However, externalizing problems functioned as a mediator in the path from suicidal behavior to sleep problems. Although our study failed to identify the proposed mediating role of externalizing problems in the effects of sleep problems on NSSI/suicidal behavior, it was important to note that hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems examined in this study only reflected two aspects of the construct of externalizing problems. Moreover, previous research has shown that hyperactivity/inattention is not consistently associated with suicidal behavior [67], while this study utilized composite scores of the hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems subscales to represent the broader dimension of externalizing problems, without separately analyzing these two dimensions in relations to sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior. Thus, further examination of the roles of other facets of externalizing problems (e.g., aggression) in the associations between sleep and NSSI/suicidal behavior is warranted. For instance, previous research has shown that sleep problems are a risk factor for aggression [68], and aggression has been found to be linked with suicidal behaviors [69]. Future research could explore whether aggression could account for the longitudinal effect of sleep problems on NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents.

On the other hand, our study provided novel insights into the focal associaiton by revealing the indirect effect of suicidal behavior on sleep problems through externalizing problems. Previous research has indicated that suicidal individuals often experience both behavioral and psychological unrest. Specifically, these individuals are frequently observed engaging in restless and repetitive behaviors, such as wringing their hands or pacing. Moreover, they report a subjective sense of restlessness and unease [54]. These behavioral and psychological unrest may contribute to the manifestation of externalizing problems. Furthermore, externalizing problems have been found to be associated with increased rumination, emotional distress, and fear, all of which can disrupt sleep [70]. Additionally, there may be biological factors associated with externalizing problems, such as altered cortisol levels [71] that may further contribute to sleep problems [72].

Collectively, the above-mentioned findings highlighted the mediating role of ERD in the vicious cycle between sleep problems and NSSI; and the mediating roles of ERD and externalizing problems in the pathway from suicidal behavior to sleep problems, thus shedding new light on the mechanisms underlying the bidirectional relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

This study displayed several major strengths. First, previous studies on the links between sleep problems, ERD/externalizing problems, NSSI/suicidal behavior have primarily been limited to cross-sectional design and evaluating unidirectional effects. The present study extended the current linear, unidirectional focus predominantly taken to unravel bidirectional effects between sleep problems, ERD/externalizing problems, and NSSI/suicidal behavior. Second, this study expanded the exploration of mechanisms underlying the relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, and disentangled the differential mediating roles of ERD and externalizing problems in these longitudinal associations. Such knowledge would provide valuable information to inform the focus and timing of interventions aiming to decrease sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior during adolescence. Third, the theoretical model of insomnia and NSSI [9] is a recently proposed model based on the study on Swedish adolescents, this study employed a new research sample by including Chinese adolescents as participants and uncovered the mechanism of relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior more comprehensively. Therefore, the current findings enriched the existing literature by evaluating the applicability of this model to the adolescent population within the Chinese cultural context and contributed to the enrichment and refinement of this model.

This study also displayed limitations. First, the research data relied on self-reports. Although self-reports are regarded as an “individual-focused” measure, future researchers should use multiple informants (e.g., parents) to decrease social desirability responding effects. Second, given that this study aimed to investigate sleep problems as a comprehensive concept, including both the quality and quantity of sleep, the two aspects of sleep were not analyzed separately in relation to other variables. Future research should explore potential differences in the results between this study and studies that examine the quality and quantity of sleep as separate components. Third, this study only examined the mediating effects of ERD and externalizing problems in the reciprocal relations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, thus, other potential mediating variables that have been proposed as mechanisms explaining the links between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, such as aggression [73], negative situational and self-appraisals [12], impaired decision-making and problem-solving [74], remain to be examined in future longitudinal research. Additionally, this study focused on the potential mediating role of externalizing problems underlying the longitudinal associations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, without considering internalizing problems. Therefore, future research should simultaneously examine the mediating roles of internalizing and externalizing problems in the focal associations.

Conclusion

This study theoretically investigated the reciprocal influences between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, as well as the mechanisms that could explain these associations in adolescents.

The findings underscored the cyclical relationship between sleep problems and suicidal behavior. Moreover, sleep problems exerted an indirect effect on NSSI through ERD, and vice versa; while ERD/externalizing problems functioned as mediators in the pathway from suicidal behavior to sleep problems.

Overall, the current study has important implications for the prevention and intervention of sleep problems, and NSSI/suicidal behavior in adolescents. First, since sleep problems exerted a significant predictive effect on adolescents’ subsequent engagement in NSSI/suicidal behavior, early evaluation and screening of sleep problems in adolescents could potentially help identify a subgroup of vulnerable individuals, specifically those who engage in NSSI/suicidal behavior. Moreover, parents should assist their children in cultivating healthy sleep habits, such as establishing a consistent sleep routine, reducing electronic device usage, and limiting caffeine consumption in the evening. Additionally, school educators can develop sleep health education programs, including initiatives such as adjusting school schedules, organizing lectures on sleep hygiene, and inviting pediatricians to conduct screenings on sleep hygiene. Second, given that suicidal behavior also had an adverse impact on sleep problems, in the clinical treatment of adolescents with suicidal tendencies, it is also important to assess their sleep problems and provide timely intervention to prevent a vicious cycle between sleep problems and suicidal behavior. Third, considering the differential mediating effects of ERD and externalizing problems in the longitudinal associations between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior, prevention and intervention strategies aimed at addressing the two mediators may be helpful in disrupting the indirect influential pathways between sleep problems and NSSI/suicidal behavior. Specifically, for youth with potential risks of self-injury or suicide, it is necessary to incorporate a specific aspect into their treatment aimed at enhancing their ability to regulate emotions, so as to develop an alternative range of adaptive behaviors for effectively managing emotions. These skills can be acquired through Dialectical Behavior Therapy [75] as well as Emotion Regulation Group Therapy [76]. Additionally, interventions targeting externalizing problems should also be implemented to help reduce sleep problems.

Data availability

Due to confidentiality agreements between the researchers and the study participants, the research data is not publicly accessible.

References

de Zambotti M, Goldstone A, Colrain IM, Baker FC (2018) Insomnia disorder in adolescence: diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Med Rev 39:12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.009

Bandel SL, Brausch AM (2018) Poor sleep associates with recent non-suicidal self-injury engagement in adolescents. Behav Sleep Med 18:81–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2018.1545652

Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM et al (2001) The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment 8:443–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/107319110100800409

Ghekiere A, Van Cauwenberg J, Vandendriessche A et al (2019) Trends in sleeping difficulties among European adolescents: Are these associated with physical inactivity and excessive screen time? Int J Public Health 64:487–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1188-1

Hysing M, Sivertsen B, Stormark KM, O’Connor RC (2015) Sleep problems and self-harm in adolescence. Brit J Psychiat 207:306–312. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.146514

Liu X, Chen H, Bo QG, Fan F, Jia CX (2017) Poor sleep quality and nightmares are associated with non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents. Eur Child Adoles Psy 26:271–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0885-7

McGlinchey EL, Courtney-Seidler EA, German M, Miller AL (2017) The role of sleep disturbance in suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents. Suicide Life-Threat 47:103–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12268

Lundh LG, Bjärehed J, Wångby-Lundh M (2013) Poor sleep as a risk factor for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. J Psychopathol Behav 35:85–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-012-9307-4

Latina D, Bauducco S, Tilton-Weaver L (2021) Insomnia symptoms and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: understanding temporal relations and mechanisms. J Sleep Res 30:e13190. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13190

Ennis CR, Short NA, Moltisanti AJ, Smith CE, Joiner TE, Taylor J (2017) Nightmares and non-suicidal self-injury: the mediating role of emotional dysregulation. Compr Psychiat 76:104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.04.003

Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K (2012) Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry 73:e1160e7. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.11r07586

Littlewood D, Kyle SD, Pratt D, Peters S, Gooding P (2017) Examining the role of psychological factors in the relationship between sleep problems and suicide. Clin Psychol Rev 54:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.03.009

Benjet C, González-Herrera I, Castro-Silva E, Méndez E, Borges G, Casanova L, Medina-Mora ME (2017) Non-suicidal self-injury in Mexican young adults: prevalence, associations with suicidal behavior and psychiatric disorders, and DSM-5 proposed diagnostic criteria. J Affect Disorders 215:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.025

Voss C, Hoyer J, Venz J, Pieper L, Beesdo-Baum K (2020) Non-suicidal self-injury and its co-occurrence with suicidal behavior: an epidemiological-study among adolescents and young adults. Acta Psychiat Scand 142:496–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13237

Franklin JC, Nock MK (2016) Non-suicidal self-injury and its relation to suicidal behavior. In: Kleespies PM (ed) The oxford handbook of behavioral emergencies and crises. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 401–416

Selby EA, Kranzler A, Fehling KB, Panza E (2015) Non-suicidal self-injury disorder: the path to diagnostic validity and final obstacles. Clin Psychol Rev 38:79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.03.003

Kaufman EA, Xia M, Fosco G et al (2016) The difficulties in emotion regulation scale short form (DERS-SF): validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. J Psychopathol Behav 38:443–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3

Kahn M, Sheppes G, Sadeh A (2013) Sleep and emotions: bidirectional links and underlying mechanisms. Int J Psychophysiol 89:218–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.05.010

Robinson K, Garisch JA, Kingi T, Brocklesby M, O’Connell A, Langlands RL, Russell L, Wilson MS (2019) Reciprocal risk: the longitudinal relationship between emotion regulation and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents.J Abnorm Child Psych 47:325–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0450-6

Carter M (2018) Sleep, emotion dysregulation, and non-suicidal Self-Injury in adolescents. Harvard University, Doctoral Dissertation.

Ward-Ciesielski EF, Winer ES, Drapeau CW, Nadorff MR (2018) Examining components of emotion regulation in relation to sleep problems and suicide risk. J Affect Disorders 241:41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.065

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, Burlington

Quach JL, Nguyen CD, Williams KE, Sciberras E (2018) Bidirectional associations between child sleep problems and internalizing and externalizing difficulties from preschool to early adolescence. Jama Pediatr 172:e174363. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4363

Liu J, Glenn AL, Cui N, Raine A (2021) Longitudinal bidirectional association between sleep and behavior problems at age 6 and 11 years. Sleep Med 83:290–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.04.039

Meszaros G, Horvath LO, Balazs J (2017) Self-injury and externalizing pathology: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry 17:160. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1326-y

Guo L, Wang W, Wang T et al (2019) Association of emotional and behavioral problems with single and multiple suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: modulated by academic performance. J Affect Disorders 258:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.085

Bauducco SV, Salihovic S, Boersma K (2019) Bidirectional associations between adolescents’ sleep problems and impulsive behavior over time. Sleep Med 1:100009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleepx.2019.100009

Martel MM, Levinson CA, Lee CA, Smith TE (2017) Impulsivity symptoms as core to the developmental externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Child Psych 45:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0148-6

Lockwood J, Daley D, Townsend E, Sayal K (2017) Impulsivity and self-harm in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur Child Adoles Psy 26:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0915-5

Liu X (1996) Reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Chinese J Psychiatr 29:103

Geng F, Fan F, Mo L, Simandl I, Liu X (2013) Sleep problems among adolescent survivors following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China: a cohort study. J Clin Psychiat 74:67–74. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m07872

Little RJA (1988) A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc 83:1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Bollen KA (1989) A new incremental ft index for general structural equation models. Sociol Method Res 17:303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

Jiang Q, Zhao F, Xie X, et al. (2020) Difficulties in emotion regulation and cyberbullying among Chinese adolescents: a mediation model of loneliness and depression. J Interpers Violence 37:NP105-NP1124.

Goodman A, Lamping DL, Ploubidis GB (2010) When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): data from British parents, teachers and children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38:1179–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x

Du Y, Kou J, Coghill D (2008) The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in China. Child Adol Psych Men 2:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-2-8

Gratz KL (2001) Measurement of deliberate self-harm: preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. J Psychopathol Behav 23:253–263. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012779403943

You J, Leung F, Lai CM, Fu K (2012) The associations between non-suicidal self-injury and borderline personality disorder features among Chinese adolescents. J Pers Disord 26:226–237. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2012.26.2.226

Kang N, You J, Huang J et al (2018) Understanding the pathways from depression to suicidal risk from the perspective of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Suicide Life-Threat 49:684–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12455

Sirin SR (2005) Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: a meta-analytic review of research. Rev Educ Res 75:417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417

Chen FF (2007) Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model 14:464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Orth U, Clark DA, Donnellan MB, Robins RW (2021) Testing prospective effects in longitudinal research: comparing seven competing cross-lagged models. J Pers Soc Psychol 120:1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000358

Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, Boelcke-Stennes K, Tellegen A (2005) Developmental cascades: linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Dev Psychol 41:733–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733

Chen C, Chen Y, Song Y (2023) Reciprocal relationship between interpersonal communication and depressive symptoms and the mediating role of resilience across two years: three-wave cross-lagged panel model. J Affect Disorders 334:358–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.121

Hamilton K, Phipps DJ, Loxton NJ, Modecki KL, Hagger MS (2023) Reciprocal relations between past behavior, implicit beliefs, and habits: a cross-lagged panel design. J Health Psychol 28:1217–1226. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053231164492

Zhang H, Miller-Cotto D, Jordan NC (2023) Estimating the co-development of executive functions and math achievement throughout the elementary grades using a cross-lagged panel model with fixed effects. Contemp Educ Psychol 72:102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102126

MacKinnon DP (2008) Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

Luijten CC, van de Bongardt D, Jongerling J, Nieboer AP (2021) Longitudinal associations among adolescents’ internalizing problems, well-being, and the quality of their relationships with their mothers, fathers, and close friends. Soc Sci Med 289:114387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114387

Yang J, Huebner ES, Tian L (2021) Transactional processes between childhood maltreatment and depressive symptoms from middle childhood to early adolescence: locus of control as a mediator. J Affect Disorders 295:216–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.040

Zhu X, Shek DT, Chu CK (2021) Internet addiction and emotional and behavioral maladjustment in Mainland Chinese adolescents: cross-lagged panel analyses. Front Psychol 12:781036. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781036

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB (2002) Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Modeling 9:233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z (2004) In search of golden rules: comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct Equ Modeling 11:320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

Kline RB (2010) Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. Guilford, New York

Ribeiro JD, Silva C, Joiner TE (2014) Overarousal interacts with a sense of fearlessness about death to predict suicide risk in a sample of clinical outpatients. Psychiat Res 218:106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.036

Joiner TE (2005) Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, Van Orden K, Witte T, Cukrowicz K, Braithwaite S, Selby E, Joiner T (2010) The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev 117:575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697

Busch KA, Fawcett J, Jacobs DG (2003) Clinical correlates of inpatient suicide. J Clin Psychiat 64:14–19

Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC et al (2010) The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev 117:575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697

Brausch AM, Gutierrez PM (2010) Differences in non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in adolescents. J Youth Adolescence 39:233–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9482-0

Talbot LS, McGlinchey EL, Kaplan KA et al (2010) Sleep deprivation in adolescents and adults: changes in affect. Emotion 10:831–841. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020138

Zohar D, Tzischinsky O, Epstein R, Lavie P (2005) The effects of sleep loss on medical residents’ emotional reactions to work events: a cognitive-energy model. Sleep 28:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/28.1.47

Raudales AM, Yang M, Schatten HT et al (2023) Daily reciprocal relations between emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury among individuals with a history of sexual assault: the influence of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Suicide Life-Threat 53:124–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12927

Franklin JC, Hessel ET, Aaron RV, Arthur MS, Heilbron N, Prinstein MJ (2010) The functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: support for cognitive-affective regulation and opponent processes from a novel psychophysiological paradigm. J Abnorm Psychol 119:850–862. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020896

Hasking P, Whitlock J, Voon D, Rose A (2016) A cognitive emotional model of NSSI: using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cognition Emotion 31:1543–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1241219

Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ (2006) Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav Res Ther 44:371–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005

Salters-Pedneault K, Tull MT, Roemer L (2004) The role of avoidance of emotional material in the anxiety disorders. Appl Prev Psychol 11:95–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appsy.2004.09.001

Weis D, Rothenberg L, Moshe L, Brent DA, Hamdan S (2015) The effect of sleep problems on suicidal risk among young adults in the presence of depressive symptoms and cognitive processes. Arch Suicide Res 19:321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2014.986697

Becker SP, Holdaway AS, Luebbe AM (2018) Suicidal behaviors in college students: frequency, sex differences, and mental health correlates including sluggish cognitive tempo. J Adolescent Health 63:181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.013

Van Veen MM, Lancel M, Beijer E, Remmelzwaal S, Rutters F (2021) The association of sleep quality and aggression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sleep Med Rev 59:101500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101500

Detullio D, Kennedy TD, Millen DH (2022) Adolescent aggression and suicidality: a meta-analysis. Aggress Violent Beh 64:101576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2021.101576

Pillai V, Steenburg LA, Ciesla JA (2014) A seven day actigraphy-based study of rumination and sleep disturbance among young adults with depressive symptoms. J Psychosom Res 77:70e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.004. 2014/07/01/.

Salis KL, Bernard K, Black SR, Dougherty LR, Klein D (2016) Examining the concurrent and longitudinal relationship between diurnal cortisol rhythms and conduct problems during childhood. Psychoneuroendocrino 71:147–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.05.021

Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Pesonen AK, Pyhala R, Paavonen EJ, Feldt K et al (2010) Poor sleep and altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical and sympatho-adrenal-medullary system activity in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 95:2254–2261. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-0943

Zschoche M, Schlarb AA (2015) Is there an association between insomnia symptoms, aggressive behavior, and suicidality in adolescents? Adolesc Health Med T 6:29–36. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S76511

McCall WV, Black CG (2013) The link between suicide and insomnia: theoretical mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep 15:389–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0389-9

Linehan M (1993) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press, New York

Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR (2015) Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Psy 54:97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009

Funding

This study was supported by the National Postdoctoral Researcher Program, China, 2023 (Grant No. GZC20230587).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY collected the research date, wrote the main manuscript text, and reviewed the manuscript. YZ wrote the main manuscript text and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standard

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (the Ethics Review Committee (IRB) of Education School, Guangzhou University) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Zhao, Y. Examining bidirectional relations between sleep problems and non-suicidal self-injury/suicidal behavior in adolescents: emotion regulation difficulties and externalizing problems as mediators. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 2397–2411 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02334-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02334-1