Abstract

Challenging behavior, such as aggression, is highly prevalent in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum and can have a devastating impact. Previous reviews of challenging behavior interventions did not include interventions targeting emotion dysregulation, a common cause of challenging behavior. We reviewed emotion dysregulation and challenging behavior interventions for preschoolers to adolescents to determine which evidence-based strategies have the most empirical support for reducing/preventing emotion dysregulation/challenging behavior. We reviewed 95 studies, including 29 group and 66 single case designs. We excluded non-behavioral/psychosocial interventions and those targeting internalizing symptoms only. We applied a coding system to identify discrete strategies based on autism practice guidelines with the addition of strategies common in childhood mental health disorders, and an evidence grading system. Strategies with the highest quality evidence (multiple randomized controlled trials with low bias risk) were Parent-Implemented Intervention, Emotion Regulation Training, Reinforcement, Visual Supports, Cognitive Behavioral/Instructional Strategies and Antecedent-Based Interventions. Regarding outcomes, most studies included challenging behavior measures, while few included emotion dysregulation measures. This review highlights the importance of teaching emotion regulation skills explicitly, positively reinforcing replacement/alternative behaviors, using visuals and metacognition, addressing stressors proactively, and involving parents. It also calls for more rigorously designed studies and for including emotion dysregulation as an outcome/mediator in future trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Challenging behavior—including aggression, self-injury, and property destruction—occur in as many as 80% of children and adolescents on the autism spectrum [1] and can have a devastating impact. It negatively affects personal and family well-being [2], significantly impairs functioning [3], contributes to teacher burnout [4], and is the most frequent cause of hospitalizations among this population [5]. A common contributor to challenging behavior and related explosive outbursts in autism is difficulties with emotion regulation [6], or emotion dysregulation, i.e., difficulties with monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional responses to environmental demands [7]. When youth on the autism spectrum do not have a repertoire of emotion regulation strategies to call on, or when they do not call upon those strategies in a timely manner to regulate their physiological and psychosocial stress [3], this may culminate in challenging behavior. Challenging behavior may serve the function of cathartic release through stress/emotional expression or may serve to otherwise bring the individual back to autonomic equilibrium by, for example, eloping from a situation the individual perceives as stressful. Indeed, individuals on the autism spectrum are more likely to experience emotion dysregulation to stressful events than their peers due to their difficulties communicating, understanding others’ behavior and responding to demands, sensitivities to sensory stimuli, insistence on sameness, and social expectations that might be perceived as emotionally overwhelming [6]. Consistent with this notion, recent literature has documented that challenging behaviors in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum are more likely to surface in response to situations placing demands that exceed their emotion regulation skills [8]. Therefore, in this framework, emotion dysregulation serves as a mediator between stress and challenging behaviors in autism [9], and is a critically important target for intervention.

Although several reviews have examined strategies designed to address challenging behavior in autism, no systematic review so far has integrated such strategies with those focused on supporting emotion regulation skills in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum. The important role of emotion dysregulation in challenging behavior, externalizing behaviors, and explosive outbursts has been well recognized in other populations [10, 11]. Indeed, recommendations and practice guidelines for challenging behaviors across other disorders include evidence-based strategies to address emotion dysregulation [12] such as Emotion Regulation Training, Mindfulness-Based Interventions, and De-escalation Training. However, these strategies have not yet been emphasized in major autism intervention and practice guidelines for challenging behavior, despite their effectiveness in other populations. This may be because well-established autism evidence practice guidelines on challenging behaviors are informed by literature reviews that do not include emotion dysregulation as a focus. The omission might reflect the epistemological and methodological tenets of behavioral disciplines [13], including applied behavior analysis (ABA), which has been most influential in the field of challenging behaviors in autism. ABA is an approach, grounded in the principles of behavioral theory, including classical and operant conditioning, and a related recognition of harnessing of antecedents and consequences to behavior and skills, through which news skills can be taught and challenging behaviors can be prevented or addressed [14,15,16]. ABA has historically focused on overt behavior as opposed to underlying “private events,” such as emotional processes (though we acknowledge this is not necessarily representative of modern ABA practices, as recognition of the importance of emotion regulation in autism intervention has taken shape over the past 1–2 decades) [17]. This is in contrast to child mental health disciplines, for which emotion processing, reactivity, and regulation are an important focus. Additionally, existing reviews on challenging behaviors have almost exclusively focused on single case design studies, which are most prominently used in the ABA field, and often exclude group-based study designs [18,19,20] which are more prominent in psychology/psychiatry fields, resulting in a limited focus on emotional dysregulation in conceptualizing challenging behavior and interventions to address challenging behavior in autism.

To address this gap and provide new opportunities for conceptualizing the integration of behavioral therapies with child mental health therapies in addressing challenging behavior in autism, the current systematic review builds and extends on the work by the National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice (NCAEP) Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder 2020 Report [21], and previous reviews on challenging behavior interventions for children and adolescents on the autism spectrum [18,19,20, 22]. We integrate strategies both for challenging behavior and emotion dysregulation in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum, rather than just strategies for emotion dysregulation alone, as the goal of the review is to extend previous literature search methods to provide a comprehensive re-examination and update on evidence supporting discrete strategies (i.e., strategies that are distinctly defined, though they may or may not be tested in combination with other strategies within intervention packages). We focus on discrete strategies to reduce challenging behavior, in light of strategies designed to address challenging behavior via addressing emotion dysregulation, and strategies targeting emotion regulation specifically (that may as a by-product also prevent challenging behavior). We note that many of the strategies designated as evidence based in NCAEP target challenging behavior indirectly through teaching replacement skills and strategies to reduce stress. We extend previous efforts by addressing the limitations of previous reviews, including expanding search terms to include both challenging behavior and emotion dysregulation, including both single case and group study designs to build upon the previous reviews in this area, and by considering interventions delivered across different settings, such as at school, home, clinic, and via telehealth.

We used the criteria for “evidence based” as set by the NCAEP and cross-referencing an evidence grading system as outlined in Harbour and Miller [23] that rates studies by experimental control and methodological quality (e.g., risk of bias) to rank order evidence-based strategies based on empirical support. We use the term “evidence-based strategies” (instead of “evidence-based practices” used in NCAEP) to better align with the broader body of research on evidence-based practices in child mental health disorders [24], as we are interested in discrete strategies rather than full intervention models.

Methods

Preregistration

Our search strategy was registered with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): registration number CRD42021241655. This review’s pre-registered protocol is available here: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021241655.

Search strategy

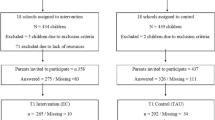

Our team followed The PRISMA 2020 guidelines throughout this systematic review [25]. We identified studies through a systematic search of published articles on interventions for children and adolescents on the autism spectrum aimed at reducing challenging behavior or regulating emotions. We searched nine electronic databases based on the NCAEP 2020 Report [21]: (1) Academic Search Premier; (2) Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); (3) Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE); (4) Educational Resource Information Center (ERIC); (5) PsycINFO; (6) PubMed; (7) Social Work Abstract; (8) Sociology Abstracts; and (9) Web of Science. We used the following search terms, modeling after and extending those included in the NCAEP 2020 Report [21]: ab(emotion* regulation OR emotion* dysregulation OR self-regulation OR self-regulation OR externaliz* OR challenging behavior* OR problem behavior* OR disruptive behavior* OR aggressi* OR irritab* OR coping skill* OR behavioral health) AND ab(Autis* OR autism spectrum disorder OR ASD OR ASC OR Asperger* OR Pervasive Developmental Disorder* OR PDD OR PDD-NOS) AND ab(intervention* OR strateg* OR trial* OR RCT OR program* OR approach* OR practice OR therap* OR treatment OR procedure OR method OR education OR curricul*) AND ab(school* OR home OR digital learning OR distance learning OR distance education OR remote learning OR remote education).. No child/adolescent focused terms or limits or limits on date of publication were included. The search was conducted on March 31, 2022. This initial search yielded 953 articles prior to eligibility coding. We found four previous reviews on challenging behavior interventions for children or adolescents on the autism spectrum and one chapter on emotion regulation interventions for children or adolescents on the autism spectrum [18,19,20, 22, 26], and we scanned their reference lists to determine if any other articles not previously included met our inclusion criteria. These reviews yielded an additional 25 articles prior to eligibility coding; therefore, our search yielded 978 articles to assess for eligibility. See Fig. 1 for article screening process and criteria used.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility of each journal article was assessed for inclusion based on the following criteria: (1) the journal article was peer reviewed; (2) it was written in (or translated into) English; (3) the study was specifically designed to target emotion regulation/dysregulation, externalizing behavior, or challenging behavior (i.e., behavior that is dangerous to the self or others, behavior that interferes with learning and development, and/or behavior that interferes with socialization or acceptance from peers - note that we did not include behaviors that can help individuals regulate their emotions, such as hand flapping, toe walking or body rocking, as long as they are not causing harm to themselves or others); (4) the study included emotion dysregulation, emotion regulation, challenging behavior, and/or externalizing behavior as an outcome measure; (5) the children or adolescents were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), pervasive developmental disorder (PDD), or any subcategories of a PDD diagnosis; (6) the intervention evaluation design was either a group-based design (e.g., RCT, pre–post with/without a control group) or a single case design (e.g., multiple baseline, alternating treatment); and (7) the intervention was designed for school, home, clinic, or remote delivery (i.e., telehealth). Exclusion criteria included: (1) medication only interventions; (2) interventions involving animals, massage, yoga, or physical therapy; (3) interventions only for adults; (4) case reports/series; or (5) interventions that targeted internalizing symptoms only. The role of emotion dysregulation in other psychopathology, such as internalizing behaviors, while recognized in the literature [11], was not included as it was outside of the focus of this review.

Initially, six raters assessed eligibility of the articles based on a review of abstracts. Abstracts were reviewed with a 20% overlap to assess inter-rater reliability (IRR = 79%; κ = 0.6), and all disagreements were reviewed with the team to reach a consensus on final determination per article. This yielded a total of 186 articles that were then included in a full-text review by four raters. All articles were double coded to determine if they met eligibility criteria (100% overlap). Raters reached high reliability (IRR = 84%; κ = 0.61). Again, all disagreements were reviewed with the team to reach a 100% consensus on final determination per article. See Appendix A for the full list of included studies.

Methods and design data extraction

The following information was extracted from each study: (1) author; (2) year; (3) country; (4) sample size; (5) sex; (6) age range; (7) IQ; (8) race/ethnicity; (9) intervention description; (10) delivery setting, i.e., the physical location where the intervention took place (school, home, clinic, or remotely via telehealth, and if school, school level, and classroom type); (11) teacher, therapist, parent, or research team mediated (i.e., the person delivering the intervention); (12) teacher/parent training methods; (13) control group description; (14) research design (quantitative, qualitative, mixed); (15) evaluation design (e.g., RCT, pre-post, multiple baseline); (16) for single case designs, number of repetitions/phases of intervention sequences; (17) for group designs, baseline group matching; and (18) reliability of primary outcome measures (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, IRR, kappa).

Evidence-based strategy coding

We based our evidence-based strategy coding system on the Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism Report (2020) by the NCAEP Review Team based at the University of North Carolina. Additional discrete strategies (i.e., strategies that are distinctly defined, see Appendix B for strategy definitions) were considered for inclusion based on these criteria for qualifying as an evidence-based strategy outlined by the NCAEP Review Team: (1) two or more group design studies conducted by at least two different researchers or research groups; (2) five or more single case design studies conducted by three different researchers or research groups and with a total of at least 20 participants across studies; or (3) a combination of one group design and at least three single case study designs conducted by at least two different researchers or research groups. Following the NCAEP Review Team’s methods, we focused on discrete intervention strategies rather than comprehensive treatment models or full intervention packages; therefore, comprehensive treatment models or full intervention packages were coded on the discrete intervention strategies included in the model or intervention package. We considered adding the following additional discrete strategies (in alphabetical order; final list that met the above criteria provided in “Results”): Behavioral Descriptions/Reflections; Behavior Contracting; Behavior Management; De-escalation; Emotion Regulation Training; Exposure; Feedback; Homework; Metaphors/Analogies; Mindfulness-Based Strategies; Physical Safety Monitoring; Punishment; Role Play and Practice; Universal Behavior Management; Interpersonal Psychotherapy; and Verbal and Physical Comfort. See Appendix B for the full strategies coding system.

Evidence-based strategy coding was double-coded (i.e., 100% overlap) by two coders (the lead coder was a PhD and developmental/experimental psychologist, along with her research student), and two additional coders (one, a PhD school psychologist, board-certified behavior analyst [BCBA] and autism intervention researcher and trainer, and the other, a PhD clinical psychologist and autism intervention researcher and trainer) completed a random selection of 20% of articles for reliability (IRR M = 92%, range 71–100%). If studies referenced previously peer-reviewed manuscripts in describing intervention components, those manuscripts were also reviewed for evidence-based strategy coding purposes. All disagreements were reviewed by the team to reach an ultimate consensus per study.

Evidence grade coding

We used a coding scheme based on the evidence-based grading system outlined by Harbour and Miller (2001) [23] to weigh evidence per study design in a two-step process. First, numbered codes were applied per study: 1 + + (RCTs with a very low risk of bias), 1 + (RCTs with a low risk of bias), 1- (RCTs with a high risk of bias), 2 + + (high-quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding, bias, or chance, and a high probability that the relationship is causal), 2 + (well-conducted case–control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding, bias or chance, and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal) and 2 − (case–control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding, bias, or chance, and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal). Studies rated 3 and 4 (non-analytic studies, case reports, case series, and expert opinions) were excluded as mentioned above in "Eligibility criteria", as they were considered to carry the least scientific evidence based on Harbour and Miller’s evidence grade coding system. Extra specificity per grading level was taken from the Group Design Quality Appraisal Form and the Single Case Design Quality Appraisal Form from the Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism Report (2020) by the NCAEP. See Appendix C for the full evidence grade coding system. All studies were independently double coded by two coders (IRR = 87% agreement) and discrepancies were reviewed to reach consensus. Ratings of individual studies included in this review ranged from 1 + to 2 – .

Second, based on Harbour and Miller (2001) [23], lettered codes were applied per evidence-based strategy based on a summary of the numbered ratings across studies: A (a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1 [i.e., RCTs] directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results), B (a body of evidence including studies rated as 2 + + [i.e., high-quality single-subject design studies] directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results), and C (a body of evidence including studies rated as 2 + directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results). Therefore, the information extracted from this coding scheme indicates which evidence-based strategies have the strongest empirical support.

Data analysis

To determine which discrete strategies had the most empirical support, we combined information from the coded strategies within articles and determined the level of evidence based on study design, and then mapped this onto whether the study showed a positive effect vs. null/negative on outcomes (whether that be challenging behavior and/or emotion dysregulation/emotion regulation skills). All extracted studies were considered when determining descriptive statistics on outcome measures (Table 1), but the percentage of studies using reliable outcome measures was noted (for questionnaires and rating scales: Cronbach's alpha/IRR ≥ 0.70, either reported in a study or previously documented; for coding of challenging behavior: inter-rater reliability on 20% of observations [≥ 80% or ≥ 0.60 kappa]). Likewise, all extracted studies were considered when populating the initial list of discrete strategies for reducing emotion dysregulation/challenging behavior (Table 2), but strategies were rank ordered by study design, i.e., group designs ranked higher than single case study designs.

For the main analysis of evidence to support discrete strategies for reducing emotion dysregulation/challenging behavior, only the highest quality studies were included, including RCTs and high-quality single-subject design studies (rated 2 + + ; see “Evidence grade coding” above and Appendix C), and the strategies were further broken down as A grade (tested in RCTs) and B grade (tested high-quality single-subject design studies only).

Results

Study characteristics

After assessing eligibility, a total of 95 articles were included in our review, which incorporated data from 2,092 children and adolescents on the autism spectrum across four continents (North America, Europe, Asia, and Oceania). These articles consisted of 29 group designs (15 RCTs, 7 with a non-randomized control group and 7 without a control group), and 66 were single case designs (42 multiple baseline/multiple probe, 12 withdrawal, 5 alternating treatments, 2 multiple-treatment, and 5 changing criterion). The number of studies per age of the individuals on the autism spectrum was as follows (mean or mode age used per study): 25 preschool (3–5 years), 56 elementary (6–11 years), 10 middle school (12–14 years), 3 high school (15–18 years), and 1 mixed (1 preschool student and 1 high-school student). As would be expected for this population, most participants (82%) were male. Most studies did not include race/ethnicity (67%), but those that did showed 60% of participant were White, 18% Hispanic, 12% Black, 8% Asian, 2% multiracial, and 0.1% Native American. Likewise, most studies did not include an IQ score (74%), but across those that mentioned IQ or functional level, 55% of studies included children and adolescents with a below average IQ and/or who had significant support needs.

Regarding setting, 46% of studies implemented the strategies primarily at school (29% special education classroom, 9% general education/inclusion classroom, 14% mixed and 48% not specified), 29% primarily at home, 18% primarily through university or community clinics, and 5% primarily remotely via telehealth platforms. The percentage of studies in which the main person who mediated the strategies were teachers or teaching staff was 24%, parents 15%, therapists 9%, researchers 21%, and 27% split across person type (4% not specified). Therefore, though the intervention may have been conducted in the school or home setting, this did not necessarily mean that interventions were mediated by teachers or parents, respectively. For example, in both settings, mediation by the research team was common (see Appendix D for information on setting vs. person who mediated the intervention per study). Training was provided to the child’s/adolescent’s educational or therapeutic team including parents in 80% of studies (20% of studies did not include training as per study report). Eighty-five studies (89%) found a positive effect on challenging behavior or emotion dysregulation outcomes (for single-subject studies, on at least 80% of participants included), and 10 studies (10%) found a null/negative effect on outcomes. In studies with a positive effect on outcomes, 49/92 (53%) performed a Functional behavior assessment (FBA) to inform strategy selection, as opposed to 2/12 (17%) of null/negative effect studies. See Appendices D and E for method details for each of the 95 included studies.

Outcome measures

As shown in Table 1, although most studies used live or videotape coding of the frequency/severity/duration of challenging behavior as an outcome measure (71%), this was more common in studies using single case relative to group designs. The next most common type of outcome measure was questionnaires or other rating measures of challenging behaviors frequency and/or intensity, followed by questionnaires or other rating measures of emotion dysregulation or self/emotion regulation. Most of the studies using these outcomes (≥ 80%) reported high reliability (criteria set same as in Appendix C: for questionnaires and rating scales, Cronbach's alpha/IRR ≥ 0.70, and for coding of challenging behavior, inter-rater reliability on 20% of observations [≥ 80% or ≥ 0.60 kappa]). Few studies (10%) included an emotion dysregulation/regulation outcome measure, and those that did were more likely to be studies employing group designs. Only five (14%) group designs and zero single-subject designs included both challenging behavior and emotion dysregulation outcomes. No studies used emotion dysregulation/regulation as a mediator of outcome. See Appendix E for primary outcome measures of each study.

Determination of “evidence-based” strategies

Table 2 shows strategies evaluated against criteria based on those set forth by the NCAEP for evidence-based strategies (described in the Methods, above). Nine strategies were added based on their criteria (making 30 total): (1) Role Play and Practice; (2) Emotion Regulation Training; (3) Mindfulness-Based Strategies; (4) Homework; (5) Metaphors/Analogies; (6) Feedback; (7) Universal Behavior Management; (8) Physical Safety Management; and (9) Delay and Denial Tolerance Training. Appendix B provides a description of all strategies evaluated, broken into those meeting criteria and those not meeting criteria for an evidence-based strategy.

Examination of evidence-based strategies by study design, school level, and delivery setting

Figure 2 displays the empirical support (number and quality of studies) for each evidence-based strategy, rank ordered for evidence with quality. Only high-quality studies were included (RCTs and highest quality single-subject design studies; see Methods section ‘Evidence grade coding’ and Appendix C for evidence grading system; [23], including 50 studies (16 group designs and 34 single-subject designs). To allow comparison of strategies empirically supported by randomized vs. non-randomized studies, strategies marked as “Grade A” include at least one RCT and the other strategies with only high-quality single-subject design studies are marked as “Grade B”. Twenty-five of the evidence-based strategies met Grade A criteria and the remaining five met Grade B criteria [23].

Evidence to support strategies for reducing emotion dysregulation/challenging behavior in high-quality studies (only 1 + , 1− and 2 + + studies were included) is displayed. Studies are broken down by school level and delivery setting. Each cell (blue/gray square) represents one study, and the shade of blue (gray) represents the quality of the study supporting the evidence-based strategy, with the darkest shade of blue (gray) representing 1 + studies (RCTs with low risk of bias), the medium blue (gray) representing 1− studies (RCTs with a higher risk of bias), and the lightest blue (gray) representing 2 + + studies (high-quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding, bias, or chance, and a high probability that the relationship is causal), as per Harbour and Miller (2001). Grade A strategies (indicated in the far-left column) include at least one RCT (i.e., studies rated 1 + and 1 – ) and Grade B studies do not (i.e., studies rated 2 + +). We do not include studies with null/negative findings (n = 11), group studies with a control group but without all identified methods to reduce bias (rated as 2 + , n = 27), or group studies without a control group (rated as 2 – , n = 6). See Appendix C for a full description on each evidence grade level and risks of bias assessed. In total, 50 articles were included in this sub-analysis. School delivery was usually mediated through teachers, behavioral support professionals, one-to-one aides, or paraprofessionals. Home delivery was usually mediated via parents. See Appendices D and E for details per study. AAC augmentative and alternative communication

As can be seen in Fig. 2, the top ten evidence-based strategies rank ordered were Parent-Implemented Intervention, Emotion Regulation Training, Reinforcement, Visual Supports, Cognitive Behavioral/Instructional Strategies, Antecedent-Based Interventions, Role Play and Practice, Social Skills Training, Naturalistic Intervention and Functional Behavioral Assessment. Two of these strategies, Role Play and Practice and Emotion Regulation Training, were not included in NCAEP or other national guidelines in the USA (e.g., the National Standards Project). Most (59%) of the evidence across all studies was for elementary school-age children (6–11 years); few studies had a mean age in the middle- (10%) or high-school (3%) range. All of the top ten strategies were tested in at least one RCT each in preschool students, except for Role Play and Practice. Additionally, Functional Communication Training and Extinction were tested in an RCT each in preschool students. In elementary school students, multiple (3–7) RCTs tested the top ten strategies and at least one RCT tested the rest of the Grade A strategies, including Self-Management, Social Narratives, Prompting, Functional Communication Training, Feedback, Mindfulness-Based Strategies, Modeling, Homework, Metaphors/Analogies, Extinction, Video Modeling, Technology-Aided Instruction and Intervention, Differential Reinforcement, Response Interruption/Redirection, Universal Behavior Management and Augmentative and Alternative Communication. By contrast, only four strategies were tested in RCTs in high-school students (Emotion Regulation Training, Role Play and Practice, Social Skills Training and Technology-Aided Instruction and Intervention), and none were tested in RCTs in middle-school students.

Although the total number of studies were conducted in the school > home > clinic setting (rank order), the level of evidence across these settings was largely similar across contexts when considering study design (i.e., there were comparable numbers of RCTs across settings). As shown in Fig. 2, regarding the top ten strategies, each strategy was tested in an RCT in school, home and clinic settings, except for Emotion Regulation Training, Role Play and Practice and Social Skills Training, which were not tested in RCTs in the home setting. Studies on challenging behavior/emotion dysregulation interventions delivered via telehealth are emerging and to date have not been tested in any RCTs. The most recent telehealth study included was conducted out of necessity due to the COVID-19 pandemic [27].

Discussion

This systematic review examined the evidence base on effective strategies to address emotional dysregulation and challenging behaviors in autism. Unlike previous reviews, our focus encompasses knowledge both of evidence-based strategies to address challenging behaviors from the behavioral analytic field and knowledge on evidence-based strategies to support emotion dysregulation from the fields of psychology and psychiatry. We identified 30 evidence-based strategies that have the most empirical support for addressing challenging behavior or/and emotion dysregulation, including 21 NCAEP-identified strategies and 9 that have been commonly used in the field childhood mental health, but were unrecognized as part of the 2020 NCAEP report. Two of these previously unrecognized evidence-based strategies—Emotion Regulation Training, training to recognize one’s own bodily, cognitive, and behavioral signs of stress and employ proactive coping or emotion regulation skills to reduce one’s own stress, and Role Play and Practice, actively role playing with others to practice newly learned behavioral skills—were rated as a top ten evidence-based strategy according to study design. This finding highlights the need to explicitly teach and actively engage children and adolescents on the autism spectrum in the recognition of their own emotional states and to help build their “toolbox” of emotion regulation strategies during times of distress, and to role play or practice other replacement behaviors.

Many of the strategies designated as evidence-based in this review targeting challenging behavior or emotion dysregulation do so indirectly through teaching replacement skills and strategies to reduce stress. The focus on skill building rather than punishing challenging behavior represents a departure from previously accepted practices (indeed, Punishment was designated as a minimal evidence strategy) and reflects the importance of framing challenging behavior in the context of lagging skills [6, 8]. At school, a behavioral episode may indicate that a child needs additional supports for example, if he/she/they demonstrate(s) escape behavior during a math lesson they may need visual supports to comprehend the math concept rather than a punishment, such as a timeout. By modifying the activity to support the individual, the escape behavior will likely decrease. In the home environment, a child that hits their sibling because they want their toy may stop this behavior with parental prompting to request the toy from their sibling paired with positively reinforcing these communication attempts. Another example in the clinic setting is that a child who self-harms may decrease this behavior through being taught how to recognize the early bodily signs of stress and use calming strategies such as sensory toys to address their sensory needs. The key to addressing the lagging skills in each of these scenarios is to first work out the function that the challenging behavior has for the child.

Indeed, fourth highest on the evidence-based strategy list (Table 2) was FBA, a strategy classified with an evidence Grade A (Fig. 2), which is a widely recognized first step in intervening on challenging behavior in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum, to determine the behavior’s function. For example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 1997/2004) requires the use of FBA to develop plans targeting challenging behaviors and improving communication in individuals with disabilities. Although we listed FBA alongside the other strategies, it is best characterized as an assessment procedure for developing a behavior intervention plan, rather than an “intervention” strategy per se. Previous reviews differ in terms of characterizing FBA as a strategy (see different approaches by the NCAEP and the National Standards Project) and previous reviews on challenging behavior in autism have drawn different conclusions regarding the central importance of FBAs. Some suggest it is not a necessary step as effectiveness does not seem to relate to completion of an FBA [19]. Others, however, suggest better outcomes relate to interventions that include FBA [18, 20], as do we. We found that studies with a positive effect on outcomes were more likely to have done an FBA than studies with null/negative effects on outcomes, which is suggestive of the critical importance of determining a behavior’s function before choosing which evidence-based strategy to implement. However important, performing FBAs in the school setting are often complicated by lack of professionals able to assess the child as many schools rely on external behavioral consultants to conduct these assessments. Given the key importance of determining a behavior’s function to create successful behavioral plans, these results highlight the need for a new implementation approach for conducting FBAs in schools. For example, including data collection and/or analysis of FBAs in the professional development and coaching of teachers and other school staff, which could build on their foundational skills and training in behavioral data collection, and could help to avoid the bottleneck that this can cause for developing and actioning behavior plans.

Given the importance of FBAs and the importance of understanding if emotion dysregulation is a driver of challenging behavior, a practical approach to the integration of the behavioral analytic and psychological intervention approaches would be to include “emotion dysregulation” as a designated function or factor intensifying other functions assessed within FBAs. Emotion dysregulation may cause a behavior by itself or may intensify a behavior that serves another common function. For example, a child may use a behavior to escape/avoid a situation due to its psychological or physiological stress, and likewise may use a behavior to achieve a sense of calm via a person/sensation; or a child who hits his peer to gain access to a toy may act more aggressively if they are emotionally dysregulated at the time. It is worth noting here that an individual may also experience emotion dysregulation more easily on a given day due to biological setting events [28] such as lack of sleep, missing a dose of medication, or experiencing trauma. Therefore, looking for patterns of emotion dysregulation relating to these factors may help to inform approaches to intervention on a given day for an individual, such as starting the day with prevention/antecedent-based strategy targeting emotion regulation, such as a relaxation activity, to bring physiological arousal back to baseline. These ideas, while not complete or comprehensive, are included here to spark debate and integration of emotion regulation/stress concepts within the FBA process, i.e., to take into account the emotional experience and stress of an individual as a possible factor contributing toward a function, so to guide appropriate intervention and supports.

Relatively few studies incorporated emotion dysregulation or emotion regulation outcome measures, and these tended to be more recent studies (since 2015), with two exemptions [29, 30], marking that as a field there is growing emphasis on emotion dysregulation in autism [6]. Therefore, this systematic review is timely, as is the first to capture this new evidence base. No studies incorporated physiological stress outcomes. Given that individuals on the autism spectrum often have difficulties expressing their emotions and stress [31,32,33], such a multimodal assessment approach could help triangulate findings or reveal insights into their behavior and response to intervention [26]. Studies using a transdisciplinary approach to examine both challenging behavior and emotion dysregulation outcomes are still emerging [29, 30, 34,35,36,37]. Future research in the area should aim to incorporate multiple assessment methods and outcome measures.

This review also highlights major gaps in the field in terms of studies covering certain developmental stages, contexts, and groups. Relatively few high-quality studies examined interventions targeting middle or high-school students on the autism spectrum (though we acknowledge there are ongoing studies targeting this age range [38]; only four strategies were tested in RCTs in high-school students, and none were tested in RCTs in middle-school students. There is a milieu of hormonal, social, and emotional changes that take place throughout middle childhood and adolescence, including new challenges and opportunities for experiencing and regulating emotions (or dysregulating) emotions, which may manifest as challenging behavior [39]. Therefore, it is important to consider only the specific evidence-based strategies tested in this age range as evidence based for this age range, given that most participants included in the review were preschool (perhaps due to the emphasis on early intervention nowadays) or elementary school students, where certain cognitive skills helpful for emotion regulation are first coming online. These findings highlight the clear need for future research to address this knowledge gap.

Moreover, our review highlighted the lack of female study participants and a lack of interventions delivered via telehealth, though we may expect more studies of the latter to emerge due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Of note, a significant limitation was the inclusion of predominantly White samples wherever race/ethnicity was indicated in studies. This severely limits the ability to apply the results on what is considered evidence based on a population-based level, since emotional dysregulation and challenging behavior may have deeper cultural biases and expectations (e.g., what is considered emotion dysregulation or challenging behavior). Future research should aim to include more racial and ethnic diversity in samples to determine if results on evidence-based strategies and considerations around choosing target behaviors generalize across racial/ethnic groups. Overall, these findings suggest the knowledge gained to date about evidence-based strategies to support children and adolescents on the autism spectrum in reducing emotion dysregulation and challenging behavior is representative only of a sub-group of younger, less racially/ethnically diverse, and mostly male children, and not necessarily applicable to the wider autism population. Further research is needed to fill each of these crucial gaps.

Interestingly, we found that the proportion of null/negative effects was much lower in single case design studies compared to group design studies, suggesting there may be publishing bias at play. The authors may choose to publish cases that have a higher rate of success in treatment, so attaining an accurate picture of null/negative effects using single case design studies may be difficult [40]. This points to the importance of routinely reporting null/negative effects to allow for a more comprehensive and unbiased examination of the literature.

Limitations

This systematic review is not without limitations. First, although the evidence grade across all evidence-based strategies within each study was given equal weight in our review, some evidence-based strategies may have been more important than others (the “active ingredients”) in producing positive intervention effects. However, no studies included in our review examined whether there were active ingredients within intervention packages. This, and the use of outcome measures that are not comparable across studies, precludes a fine-grained analysis of active ingredients within different intervention packages. Examining active ingredients of challenging behavior/emotion dysregulation interventions in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum is an important future direction for the field. We maintain, however, that our results still provide actionable insight on discrete strategies that have the most empirical support as the discrete strategies were examined not only within intervention packages, but rather across the entire literature to date including different combinations of discrete strategies within studies.

Additionally, for consistency, we limited coding of the discrete strategies to the articles, or if studies referenced previously peer-reviewed manuscripts in describing intervention components, those manuscripts were also reviewed. However, for intervention packages, this may mean that we missed discrete strategies that are in intervention manuals, but not described in the peer-reviewed publications. Finally, our search criteria may have presented biases as gray/unpublished literature and articles not translated to English were excluded. As such, our study is not exempt from publication bias or selection bias as relevant articles (with both positive and null/negative effects) may have been missed.

Conclusions

This systematic review synthesizes knowledge of evidence-based strategies to address challenging behavior in autism from the behavioral analytic field with the knowledge of evidence-based strategies to support emotion dysregulation from the fields of psychology and psychiatry. This review highlights the importance of teaching emotion regulation skills to children and adolescents on the autism spectrum explicitly, positively reinforcing their replacement/alternative behaviors, using visuals and metacognition to teach them skills, addressing their stressors proactively, and involving their parents. Our hope is that the findings of the current systematic review will facilitate further development, demonstration, and dissemination of evidence-based practices to support children and adolescents on the autism spectrum who engage in challenging behaviors more equitably and effectively.

Data, material, and code

All data, coding schemes, and search syntax are available either in the manuscript or in the supplementary information.

References

Hattier MA, Matson JL, Belva BC, Horovitz M (2011) The occurrence of challenging behaviours in children with autism spectrum disorders and atypical development. Dev Neurorehab 14(4):221–229

Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J (2006) The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res 50(3):172–183

Cohen IL, Yoo JH, Goodwin MS, Moskowitz L (2011) Assessing challenging behaviors in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Prevalence, rating scales, and autonomic indicators. Int Handb Autism Pervas Dev Dis Springer. p. 247–270. Available from: http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/chapter/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8065-6_15 [Accessed Apr 3, 2016]

Hastings RP, Brown T (2002) Coping strategies and the impact of challenging behaviors on special educators’ burnout. Ment Retard 40(2):148–156

Siegel M, Gabriels RL (2014) Psychiatric hospital treatment of children with autism and serious behavioral disturbance. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 23(1):125–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2013.07.004

Mazefsky CA, Herrington J, Siegel M, Scarpa A, Maddox BB, Scahill L, White SW (2013) The role of emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(7):679–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.006

Thompson RA (1994) Emotion regulation: a theme in search of definition. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 59(2–3):25–52

Maddox BB, Cleary P, Kuschner ES, Miller JS, Armour AC, Guy L, Kenworthy L, Schultz RT, Yerys BE (2017) Lagging skills contribute to challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability. Autism 22: 898–906 https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317712651

Siegel M (2018) Arousal, emotion regulation and challenging behaviors: Insights from the Autism Inpatient Collection

Carlson GA, Singh MK (2021) Emotion dysregulation and outbursts in children and adolescents: Part I

Beauchaine TP (2015) Future directions in emotion dysregulation and youth psychopathology. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 44(5):875–896

Walter HJ, Bukstein OG, Abright AR, Keable H, Ramtekkar U, Ripperger-Suhler J, Rockhill C (2020) Clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry Elsevier 59(10):1107–1124

Vivanti G, Messinger DS (2021) Theories of autism and autism treatment from the dsm iii through the present and beyond: impact on research and practice. J Autism Dev Disord Springer; 1–12

Demchak M, Sutter C, Grumstrup B, Forsyth A, Grattan J, Molina L, Fields CJ (2020) Applied behavior analysis: Dispelling associated myths. Interv Sch Clin SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA 55(5):307–312

Lovaas OI (1987) Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. J Consult Clin Psychol 55(1):3–9

Lovaas OI, Smith T (2003) Early and intensive behavioral intervention in autism

Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR (1968) Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J Appl Behav Anal Soc Experim Anal Behav 1(1):91

Horner RH, Carr EG, Strain PS, Todd AW, Reed HK (2002) Problem behavior interventions for young children with autism: A research synthesis. J Autism Dev Disord Springer; 32(5):423–446

Machalicek W, O’Reilly MF, Beretvas N, Sigafoos J, Lancioni GE (2007) A review of interventions to reduce challenging behavior in school settings for students with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 1(3):229–246

Martinez JR, Werch BL, Conroy MA (2016) School-based interventions targeting challenging behaviors exhibited by young children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Educ Train Autism Dev Disabil JSTOR 265–280

Steinbrenner JR, Hume K, Odom SL, Morin KL, Nowell SW, Tomaszewski B, Szendrey S, McIntyre NS, Yücesoy-Özkan S, Savage MN (2020) Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with Autism. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice Review Team

Conroy MA, Dunlap G, Clarke S, Alter PJ (2005) A descriptive analysis of positive behavioral intervention research with young children with challenging behavior. Top Early Child Spec Educ Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA 25(3):157–166

Harbour R, Miller J (2001) A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ 323(7308):334

Brookman-Frazee L, Stadnick NA, Lind T, Roesch S, Terrones L, Barnett ML, Regan J, Kennedy CA, F Garland A, Lau AS (2021) Therapist-observer concordance in ratings of EBP strategy delivery: Challenges and targeted directions in pursuing pragmatic measurement in children’s mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res Springer; 48:155–170

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ British Med J Publish Group; 372:n71

Beck KB, Conner CM, Breitenfeldt KE, Northrup JB, White SW, Mazefsky CA (2020) Assessment and treatment of emotion regulation impairment in autism spectrum disorder across the life span: Current state of the science and future directions. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin Elsevier 29(3):527–542

Gerow S, Radhakrishnan S, Davis TN, Zambrano J, Avery S, Cosottile DW, Exline E (2021) Parent-implemented brief functional analysis and treatment with coaching via telehealth. J Appl Behav Anal Wiley Online Library 54(1):54–69

Carr EG, Smith CE (1995) Biological setting events for self-injury. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev Wiley Online Library 1(2):94–98

Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S, Levin I (2007) A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural intervention for anger management in children diagnosed with Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord Springer 37(7):1203–1214

Scarpa A, Reyes NM (2011) Improving emotion regulation with CBT in young children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Cambridge University Press

Nuske HJ, Vivanti G, Dissanayake C (2013) Are emotion impairments unique to, universal, or specific in autism spectrum disorder? A comprehensive review. Cogn Emot 27(6):1042–1061. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.762900

Nuske HJ, Finkel E, Pellecchia M, Herrington JD, Parma V, Hedley D, Dissanayake C (2018) A window of opportunity for preventing challenging behavior: Increase in heartrate prior to episodes of challenging behavior in preschoolers with autism

Nuske HJ, Hedley D, Tomczuk L, Finkel E, Thomson P, Dissanayake C (2018) Emotional coherence difficulties in preschoolers with autism: evidence from internal physiological and external communicative discoordination

Swain D, Murphy H, Hassenfeldt T, Lorenzi J, Scarpa A (2019) Evaluating response to group CBT in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Cogn Behav Ther 1:12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X19000011

Weiss JA, Thomson K, Riosa PB, Albaum C, Chan V, Maughan A, Tablon P, Black K (2018) A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy to improve emotion regulation in children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 59(11):1180–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12915

Mackay BA, Shochet IM, Orr JA (2017) A pilot randomised controlled trial of a school-based resilience intervention to prevent depressive symptoms for young adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a mixed methods analysis. J Autism Dev Disord Springer 47(11):3458–3478

Parent V, Birtwell KB, Lambright N, DuBard M (2016) Combining CBT and behavior-analytic approaches to target severe emotion dysregulation in verbal youth with ASD and ID. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil Taylor & Francis 9(1–2):60–82

Mazefsky C (2021) Emotion Awareness and Skills Enhancement (EASE) Program: A Clinical Trial. clinicaltrials.gov; 2020 Aug. Report No.: NCT03432832. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03432832 [Accessed Jul 1, 2021]

Cole PM (2014) Moving ahead in the study of the development of emotion regulation. Int J Behav Dev Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England 38(2):203–207

Crowley SM, Sandbank MP, Bottema-Beutel K, Woynaroski TG (2021) The quality of studies in autism early childhood intervention research. INSAR 2021 INSAR

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), grant K01MH12050 (PI: Dr. Heather J. Nuske). NIMH had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Below, we state author contributions by author initials using the CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) system. HJN: conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. AY: conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. FYK: conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; project administration; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. EP: data curation; investigation; methodology; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. BA: data curation; investigation; validation; writing—original draft. mp: conceptualization; methodology; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. MP: methodology; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. GV: conceptualization; methodology; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. CAM: conceptualization; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. LBF: conceptualization; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. JCP: conceptualization; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. MSG: conceptualization; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. DSM: conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Nuske consults with two digital health companies, Songbird Therapy and Pletly. Dr. Mazefsky receives royalties from Oxford University Press and is on the scientific advisory board for the Brain and Behavior Foundation. Dr. McPartland consults with Customer Value Partners, Bridgebio, Determined Health, and BlackThorn Therapeutics, has received research funding from Janssen Research and Development, serves on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Pastorus and Modern Clinics, and receives royalties from Guilford Press, Lambert, and Springer. All are outside the scope of the submitted work. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval and consent

No primary data collection was conducted as part of this systematic review.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

787_2023_2298_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 157 KB) Please see Appendix A for the full list of articles reviewed, Appendix B for strategy definitions, Appendix C for the numbered evidence grade coding system, Appendix D for methods across all included studies, Appendix E for evidence based strategies, design and evidence ratings across all included studies, and Appendix F for articles excluded after full-text review.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nuske, H.J., Young, A.V., Khan, F. et al. Systematic review: emotion dysregulation and challenging behavior interventions for children and adolescents on the autism spectrum with graded key evidence-based strategy recommendations. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 1963–1976 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02298-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02298-2